Abstract

In patients with radiculopathy due to degenerative disease in the cervical spine, surgical outcome is still presenting with moderate results. The preoperative investigations consist of clinical investigation, careful history and most often magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical spine. When MRI shows multilevel degeneration, different strategies are used for indicating which nerve root/roots are affected. Some authors use selective diagnostic nerve root blocks (SNRB) for segregating pain mediating nerve roots from non-pain mediators in such patients. The aim of the present study is to assess the ability of transforaminal SNRB to correlate clinical symptoms with MRI findings in patients with cervical radiculopathy and a two-level MRI degeneration, on the same side as the radicular pain. Thirty consecutive patients with cervical radiculopathy and two levels MRI pathology on the same side as the radicular pain were studied with SNRBs at both levels. All patients underwent clinical investigation and neck and arm pain assessment with visual analogue scales (VAS) before and after the blocks. The results from the SNRBs were compared to the clinical findings from neurological investigation as well as the MRI pathology and treatment results. Correlation between SNRB results and the level with most severe degree of MRI degeneration were 60% and correlation between SNRB results and levels decided by neurological deficits/dermatome radicular pain distribution were 28%. Twenty-two of the 30 patients underwent treatment guided by the SNRB results and 18 reported good/excellent outcome results. We conclude that the degree of MRI pathology, neurological investigation and the pain distribution in the arm are not reliable parameters enough when deciding the affected nerve root/roots in patients with cervical radiculopathy and a two-level degenerative disease in the cervical spine. SNRB might be a helpful tool together with clinical findings/history and MRI of the cervical spine when performing preoperative investigations in patients with two or more level of degeneration presenting with radicular pain that can be attributed to the degenerative findings.

Keywords: Diagnostic nerve-root block, Radiculopathy, MRI, Cervical spine, Treatment

Introduction

Surgical treatment of patients with cervical radiculopathy attributed to degenerative disease is still associated with moderate outcome results, although the fact that introduction of MRI radically has improved our perception of the morphological anatomical pathology. In a recent multicenter study including 51 surgically treated patients, significant residual pain persisted at follow up in 26% of the patients [25]. Is this shortcoming due to incorrect diagnosis, surgery at wrong level/levels, development of irreversible nerve root damage or the development of chronically pain syndromes?

For better understanding of these problems, many authors have used diagnostic as well as therapeutic injections for investigation and treatment of painful degenerative spinal disease, especially in the lumbar spine [1, 6, 11, 12, 14, 26, 29]. The value of these injections is continuously under debate, and the main reason for this is that they are used for diagnosis and treatment of many different spinal disorders: low back pain, neck pain, lumbar/cervical facet syndromes, discogenic pain and radicular pain [10, 24]. Our own experience is that diagnostic selective nerve root blocks (SNRB) with local anaesthetics, might provide information about root origin of radicular pain, when the blocks are performed guided by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings and clinical symptoms in the lumbar as well as in the cervical spine [11]. In patients with cervical radiculopathy and multilevel degeneration, it is often difficult to define the affected root/roots from clinical symptoms and MRI only. Not seldom, MRI shows significant degenerative pathology at more than one level, on the same (but often also on the opposite) side from the patients symptoms. Degenerative MRI changes occur in the cervical spine frequently also in persons without symptoms [4, 5, 17, 27]. MRI provides only morphological information and does not tell the clinical significance of the findings.

Clinical examination in some patients reveals sensory and/or motor deficits combined with the absence of tendon reflexes, indicating a certain nerve-root affection, while other patients present with radicular pain of a non-typical distribution [3]. Analyses of referred pain distribution from cervical nerve roots have shown only 50% correlation to the classical sensory dermatome [27]. The frequent occurrence of anastomoses between cervical nerve roots, both intra and extradurally and between the different components in the brachial plexus, may contribute to the clinical diagnostic problems [22]. Accordingly, the pain distribution in the neck-shoulder-arm area is not a reliable parameter when determining its root-origin in patients with cervical radiculopathy. Furthermore, common painful disorders in the shoulder may present with symptoms difficult to separate from cervical radiculopathy [18]. As radicular pain is the dominant problem in patients with cervical radiculopathy and the major treatment goal is to minimize this pain, it is logical to use a method to distinguish pain mediating nerve roots from non-pain mediating roots.

In this study, we report our experience in a series of patients with cervical radiculopathy, combined with a strictly two-level morphological pathology evaluated by clinical findings, MRI and a SNRB technique.

Clinical material

The present prospective study includes 30 consecutive patients, 18 women and 12 men, presenting with cervico-brachialgia. All patients were referred to the Department of Neurosurgery for evaluation and, if necessary, surgical intervention. Mean age was 53 (range: 35–66) years, and mean symptom duration was 31 (range: 2–120) months (Table 1). Inclusion criteria were cervico-brachialgia with corresponding significant degenerative MRI findings at two levels, on the same side as the symptoms. To be classified as significant, the degenerative changes must have a close relation to the nerve roots. History and clinical findings have to indicate a cervical nerve root origin with pain radiating from the neck into the arm. Patients with diffuse non-radiating pain and patients with spinal cord compression and/or myelopathy were excluded. Three patients had had previous surgery for similar symptoms and were now readmitted because of new symptoms.

Table 1.

Patient data: sex (f=female, m=male), symptom (a=neck pain, b=brachial pain, c=motor deficits, d=sensory deficits), duration (months), diagnosis (I=soft disc, II=hard disc (soft disc and osteophytes), III=foraminal stenosis)

| No | Age | Sex | Symptoms | Duration | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 51 | m | abcd | 4 | I |

| 2 | 55 | m | abc | 24 | III |

| 3 | 64 | m | abd | 75 | III |

| 4 | 57 | f | ab | 120 | III |

| 5 | 51 | f | abc | 84 | II, III |

| 6 | 48 | f | ab | 2 | II, III |

| 7 | 51 | m | ab | 38 | II, III |

| 8 | 43 | f | abd | 54 | I |

| 9 | 61 | f | abd | 29 | III |

| 10 | 59 | f | abcd | 17 | III |

| 11 | 35 | f | abd | 60 | II, III |

| 12 | 53 | m | abd | 8 | II, III |

| 13 | 57 | f | abd | 10 | II, III |

| 14 | 64 | m | ab | 13 | III |

| 15 | 55 | f | abc | 12 | III |

| 16 | 66 | f | abd | 60 | III |

| 17 | 47 | m | abd | 6 | II, III |

| 18 | 49 | f | abd | 6 | II |

| 19 | 55 | f | abcd | 84 | II, III |

| 20 | 46 | f | abd | 12 | I |

| 21 | 56 | f | ab | 24 | II |

| 22 | 55 | f | ab | 20 | III |

| 23 | 40 | m | ab | 6 | II, III |

| 24 | 51 | f | abcd | 7 | II, III |

| 25 | 58 | f | abcd | 18 | III |

| 26 | 62 | f | abcd | 36 | III |

| 27 | 46 | m | abd | 12 | III |

| 28 | 60 | m | abcd | 29 | III |

| 29 | 41 | m | abc | 35 | III |

| 30 | 60 | m | ab | 25 | III |

All patients were informed and accepted to participate in the study.

Clinical presentation

All 30 patients experienced neck pain and radicular distribution of arm pain reaching below the elbow. Eleven patients had sensory disturbances. Four patients presented with motor deficit. Seven had both motor and sensory deficits. Eight of the 30 patients had no neurological deficits.

Eighteen of the patients also presented with shoulder pain and 14 with headache (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical presentations for all 30 patients

| Clinical presentation | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Radicular pain only | 8 |

| Radicular pain and sensory disturbance | 11 |

| Radicular pain and motor disturbance | 4 |

| Radicular pain, motor and sensory disturbance | 7 |

| Headache | 14 |

| Shoulder pain | 18 |

MRI presentation

Twenty-two patients showed significant degenerative MRI pathology at the C5/C6 and C6/C7 levels, three at the C4/C5 and C5/C6 levels, two had C6/C7 and C7/C8, one C5/C6 and C7/Th1 and two C3/C4 and C5/C6 pathology.

Method

All patients in the study were clinically examined in the outpatient clinic by a neurosurgeon after MRI of the cervical spine.

The clinically suspected, affected nerve root/roots were defined by the neurological deficits (motor strength and/or sensory deficit and/or changes in tendon reflexes). In those patients who presented with neck pain and radicular pain distribution and without neurological deficits, the distribution of the radicular arm pain in relation to the sensory dermatomes defined the clinical level. SNRB were then performed, on the levels with MRI pathology on the same side as the patient’s radicular pain.

MRI grading/evaluation

The MRI findings were graded by a neuroradiologist as slight, moderate or severe. This grading was based on comparison between levels with pathology and levels with normal anatomy in the same patient. Slight degeneration was defined as reduction of the area of the neuroforamen with at least 25%, moderate if reduction was at least 50% and severe if the area of the neuroforamen was reduced with at least 75%.

MRI evaluation was performed in several steps. The investigation was initially evaluated by an MRI trained radiologist at the referring hospital, secondly re-evaluated by a neuroradiologist at the University Hospital and demonstrated and discussed at the clinical conference together with the neurosurgeon. Then the patients were investigated at the outpatient clinic and the symptoms and clinical findings were correlated to the MRI findings and root block levels were decided. Immediately prior to the root blocks, the MRI studies were once again re-evaluated by the neuroradiologist performing the blocks. In patients with unexpected results from the blocks, a further evaluation of the MRI and the root block images were performed together with the clinical findings.

Block logistics

All patients underwent nerve root block at the two levels with pathology on MRI, starting at the inferior level. No analgesics were given within 12 h before the SNRB. At least 4 h had to elapse between the first and the second block in order to reduce the risk of persisting effect from the first injection. In all the patients, both blocks were performed on the same day.

The patients underwent clinical examination 30 min before the first SNRB and depicted at the same time their arm and neck pain on a visual analogue scale (VAS). If the described pain increased by provocative manoeuvres, flexion, extension or rotation, in the cervical spine, this was also noted on the VAS.

Thirty min after the first SNRB, the clinical examination and VAS recording was repeated, and 4 h later again, followed by the same injection procedure at the superior level.

The pre-and post-block examinations were performed by a neurosurgeon. The VAS assessments were performed by a neurosurgeon or by a specially trained physiotherapist and a neuroradiologist performed the nerve-root block.

Root block technique

The blocks were performed in an X-ray suite with the patient sitting in a chair that can be turned horizontally. The technique used was basically similar to the lateral approach described by Kikuchi [12, 13] but performed with the use of c-arm fluoroscopy. A 0.7-mm needle with mandrin, 40 or 75 mm long, was used. No subcutaneous local anaesthetics were given.

Perineural needle position in the vertebral foramen was confirmed in all patients with the use of contrast media. Then 1/2 ml of Mepivacaine (CarbocainR, Astra, Södertälje, Sweden) 10 mg/ml was injected.

Evaluation of root block

If the patient reported a subjective arm pain-reduction, with a corresponding VAS reduction of 50% or more, the root was classified as significant for mediating the radicular pain.

When evaluating headache and shoulder pain the same criteria for significant pain reduction were used.

Comparison of MRI findings to results from SNRB and neurological investigation

If the MRI presented with equal degeneration at both disc levels and the SNRB and/or the neurological investigation indicated one or both of the related two nerve roots to be affected, we decided a correlation to exist.

Treatment decisions

Significant subjective radicular pain and corresponding disability combined with significant MRI findings and positive SNRB at one or two levels were indications for treatment.

At our hospital, we use transforaminal steroid injections for the treatment of cervical radiculopathy as an alternative to surgery. We give a series of three steroid injections within a period of 6–8 weeks. We use 1 ml DepomedrolR (40 mg/ml) combined with 0.5 ml CarbocainR, 10 mg/ml, in every single injection. If no longstanding effect from steroid injections develops, the next step will be surgical decompression and fusion. In the present study some patients preferred surgery as initial treatment and did not undergo steroid injections. Two patients had a good effect from the first steroid injection and did not want any further injections. All of the surgically treated patients underwent anterior microsurgical discectomy, posterior bony spurs were removed and if necessary the posterior ligament was opened. Fusions were performed by cage technique in single level and autologous bone graft with plating in two adjacent levels disease. Conservative treatment i.e.; physiotherapy and/or ergonomic adjustments were performed in those patients who were not suitable/motivated for surgery or were considered as poor surgical candidates.

Follow up

All the 30 patients were followed at the outpatient clinic combined with a telephone follow up. Outcome results are according to Odom’s criteria [20].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed on the outcome results from the three different treatment options using a computer software package (SPSS, release 11.0.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

Results from SNRB

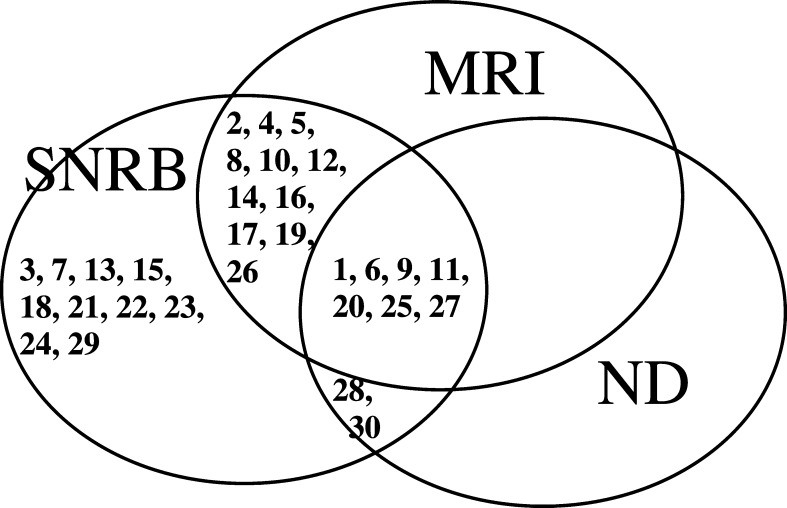

The block procedure was successful at one level in 18 patients. Eleven patients reported a significant block effect from both levels (see Method). One of the 30 patients experienced no pain reduction at all (Fig. 1). Furthermore, 11 of the 14 patients with associated headache experienced significant headache reduction. Fifteen of the 18 patients with associated shoulder pain experienced significant shoulder pain reduction.

Fig. 1.

SNRB results and correlation to MRI findings for all 30 patients

In the total series, the SNRB correlated to the most severely degenerated level according to the MRI findings in 17 of the 30 patients (see Methods section), to the level decided by the neurological deficits in eight patients and to radicular pain distribution according to the classical dermatomes in seven (Table 3).

Table 3.

Showing the two nerve roots presenting with MRI pathology and consequently investigated by SNRB for all patients and comparison of affected nerve root/roots as demonstrated by the different used investigations

| A | B | C | D | E | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6, 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| 2 | 7, 8 | 7 | 7 | 7, 8 | 8 |

| 3 | 5, 6 | 6, 8 | 6, 8 | 6 | 5, 6 |

| 4 | 6, 7 | 6 | 6 | 6, 7 | 6, 7 |

| 5 | 6, 7 | 6 | 6 | 6, 7 | 6, 7 |

| 6 | 6, 7 | 5, 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 7 | 6, 7 | 6 | 6, 7 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 6, 7 | 6, 7 | 6, 7 | 7 | 7 |

| 9 | 6, 7 | 6, 7 | 6, 7 | 6, 7 | 6, 7 |

| 10 | 6, 7 | 7, 8 | 7, 8 | 6, 7 | 6, 7 |

| 11 | 6, 7 | 6 | 6 | 6, 7 | 6 |

| 12 | 6, 7 | 8 | 8 | 6, 7 | 6 |

| 13 | 6, 7 | 6, 7 | 5, 6, 7 | 6 | 7 |

| 14 | 6, 7 | 6 | 6 | 6, 7 | 6, 7 |

| 15 | 6, 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6, 7 |

| 16 | 4, 6 | 8 | 6, 7 | 6 | 6 |

| 17 | 6, 7 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| 18 | 6, 7 | 7 | 7, 8 | 7 | 6, 7 |

| 19 | 6, 7 | 8 | 6, 8 | 6 | 6 |

| 20 | 6, 7 | 7 | 6, 7 | 7 | 7 |

| 21 | 6, 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6, 7 |

| 22 | 6, 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| 23 | 4, 6 | 7 | 5, 6, 7 | 6 | 4 |

| 24 | 6, 7 | 8 | 7, 8 | 6 | 6, 7 |

| 25 | 7, 8 | 7, 8 | 7, 8 | 7, 8 | 7, 8 |

| 26 | 6, 7 | 6, 7 | 6, 7, 8 | 6 | 6 |

| 27 | 5, 6 | 6 | 6, 7 | 5, 6 | 6 |

| 28 | 6, 7 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 |

| 29 | 5, 6 | 6, 7 | 7 | 5 | 0 |

| 30 | 6, 7, (8) | 8 | 8 | 6 | 8 |

A, Patient number.

B, Nerve roots presenting with MRI pathology and investigated by SNRB.

C, Affected nerve root/roots as demonstrated by neurological deficits during clinical examination.

D, Affected nerve root/roots as demonstrated by the dermatomal distribution of pain.

E, Most severely affected nerve root/roots as demonstrated by the MRI findings. If one nerve root is more affected than the other only one is mentioned. If the two nerve root are equally affected both is mentioned.

F, Affected nerve root/roots as demonstrated by positive response to SNRB.

Patients with one-level positive SNRB

Of the 18 patients with positive SNRB at one level, 12 correlated to the most severely degenerated level as seen on the MRI. In six patients, SNRB correlated to a level with less MRI pathology. One patient (no. 30) presented with MRI pathology related to the C6 and C7 nerve roots but did not respond to the SNRB at these levels (Fig. 1) (Table 3). The clinical findings and the pain distribution strongly pointed out the C8 nerve root but at this level the MRI was without pathology. Because of the clinical symptoms, an SNRB at the C8 root was performed, which turned out to be successful. Treatment with transforaminal steroid injections guided by the SNRB made the patient free from symptoms.

Patients with two-levels positive SNRB

Of the 11 patients with positive SNRB at two levels, 6 correlated to the MRI findings, i.e. the morphological pathology was equal at both levels. Six of these 11 patients also reported significant selective pain reduction in two different dermatomes from the two blocks, i.e. SNRB at the first level reduced pain in one area of the arm, while SNRB at the other level reduced pain in another area of the arm.

Correlation between neurological investigation, MRI and SNRB

In 15 of the 30 patients, the level decided by the neurological deficits correlated to the MRI findings. In these 15 patients only 6 correlated further to the SNRB (see Methods section) (Table 3).

Treatment results

Twenty-two of the 30 patients underwent treatment with surgery or transforaminal steroid injections, 13 at one and 9 at two levels. Eighteen of these 22 patients presented with good/excellent outcome results (82%). Of the 13 patients treated at one level, 9 had good/excellent results (69%) and out of the 9 treated at two levels, all 9 (100%) had good/excellent results. The 11 surgically treated patients presented with good/excellent outcome in 9 (82%) and the 13 patients treated with transforaminal steroid injections presented with good/excellent outcome in 9 (69%). Two of the patients initially treated with steroid injections had a latter surgical decompression and fusion due to returning symptoms (Table 4). The remaining eight patients were treated conservatively with work adjustments and physiotherapy. Four of these reported satisfactory/good/excellent results while in the other four treatments had no effect. Two of the conservatively treated patients with good/excellent results reported longstanding radicular pain reduction from the diagnostic block.

Table 4.

Treatments, follow up and treatment results for all 30 patients

| Patient number | Treatment | Follow up (months) | Outcome (Odom) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Series of 3 steroid injections followed by surgery | 20 | Good |

| 2 | Conservative | 6 | Satisfactory |

| 3 | Series of 3 steroid injections | 48 | Excellent |

| 4 | Surgery | 48 | Excellent |

| 5 | Surgery | 41 | Excellent |

| 6 | Conservative | 15 | Excellent |

| 7 | Series of 3 steroid injections | 21 | Poor |

| 8 | Surgery | 44 | Excellent |

| 9 | Two series of 3 steroid injections | 31 | Excellent |

| 10 | Conservative | 55 | Good |

| 11 | Series of 3 steroid injections | 34 | Excellent |

| 12 | Conservative, | 44 | Good |

| 13 | Series of 3 steroid injections | 27 | Poor |

| 14 | Series of 3 steroid injections | 9 | Good |

| 15 | Series of 3 steroid injections | 54 | Good |

| 16 | Surgery | 16 | Satisfactory |

| 17 | Surgery | 47 | Excellent |

| 18 | Series of 3 steroid injections followed by surgery | 31 | Excellent |

| 19 | Conservative | 20 | Poor |

| 20 | Surgery | 23 | Poor |

| 21 | Conservative | 26 | Poor |

| 22 | Conservative | 62 | Poor |

| 23 | One steroid injection | 54 | Excellent |

| 24 | Surgery | 11 | Good |

| 25 | Series of 3 steroid injections | 16 | Excellent |

| 26 | Series of 3 steroid injections | 21 | Good |

| 27 | Surgery | 6 | Excellent |

| 28 | Surgery | 45 | Excellent |

| 29 | Conservative | 25 | Poor |

| 30 | One steroid injection | 24 | Excellent |

All patients were followed up with a mean follow up time of 31 months (6–60) (Table 4).

Statistical analysis

Comparison of the three different treatment methods revealed on Kruskal–Wallis test a significant difference in outcome results between the treatments (P=0.043). Further comparison in Mann–Whitney test showed a significantly better outcome result in patients treated with surgery (P=0.018) and steroid injections (P=0.044) in comparison to conservative treatment. Comparison of surgical treatment and treatment with steroid injections revealed no significant difference in outcome results (P=0.81).

Complications

One patient fainted during the SNRB but was able to participate in both injection procedures. One patient reported vertigo lasting a few minutes after the injection.

Discussion

We found the transforaminal nerve block technique easy to perform in the cervical spine and we have had no serious complication since we started 7 years ago. However, the risks for damaging the nerve root, perforating the vertebral artery and intradural injection, when performing the root block, have to be borne in mind [7, 9, 23].

Our strategy to reduce the rate of false SNRB results and sharpen the instrument for more reliable pain estimation is based first on the introduction of provocation of the cervical spine, as described in the Method section, and thereby stressing the mechanical component [19]. Second, by adding a verbal subjective pain report from the patients, complementary to the VAS, when evaluating the SNRB. Third, by conforming correct needle position with the help of a small amount of contrast medium injected prior to the injection of the active drug.

Possible structures affected by the SNRB

The injected substance is administrated to an area where both dorsal and ventral ramus of the nerve root as well as the ganglion might be affected. The dorsal rami are supplying the deep neck muscles as well as the facet joints with pain fibres [6]. Also the local anaesthetics might reach the vertebral artery. Adjacent nerve roots as well as extra spinal muscle fibres might be affected, especially if the needle has a position outside the foramen.

Root block evaluation

If the SNRB only gave positive response at one nerve root, only this nerve root was considered affected and significant for the patient’s symptoms. Eighteen patients presented with significant SNRB response at one level and six of these were significant at the least affected level according to MRI and in one patient at a level without MRI pathology at all. Five of these six patients were treated guided by the SNRB and four had good/excellent outcome results.

Figure 1 shows that 11 of the patients had a successful SNRB at two nerve roots. Out of these, five patients reported positive effect from the SNRB at both nerve roots with identical distribution of pain reduction from the two root blocks. One explanation to these findings might be intradural nerve root connections that, according to Perneczky [22], are occurring in a high frequency between nerve roots in the cervical spine. If the two successful blocks reduced pain in two different parts of the arm, we consider both nerve roots significant for the patients symptoms.

Correlation between SNRB, MRI pathology and clinical presentation

The correlation between the diagnostic SNRB and the most severely degenerated level on MRI was only 60%. The low correlation between SNRB and the radicular pain distribution in the arm in correlation to the classical dermatomes (24%) further confirms the results presented by Slipman et al. [28] who stimulated individual cervical nerve roots mechanically and only found a 50% correlation to the classical dermatomes. Also, neurological deficits in terms of nerve root/roots does not correlate well to the most severely degenerated MRI levels/SNRB results.

Reasons for misjudgement of clinical symptoms

Atypical presentation is probably possible from all nerve roots in the cervical spine. Recently, in a large series of patients, 15% of atypical presentation from C7 radiculopathy was described [8]. Anastomosis between nerve structures at different levels in the nerve tree, intra as well as extradurally frequently occur according to human cadaver studies [21, 22]. Such studies have also shown 30% anatomical incorporation of C4 into the brachial plexus. The C4 nerve root is not commonly supposed to contribute to the brachial plexus according to neurophysiological literature/charts [15]. Taken together, this might contribute to unexpected clinical presentation from different nerve roots. In our study, one patient presented with radicular arm-pain from the C4 nerve root according to the SNRB.

Persisting radicular pain reduction from SNRB

Two of the 30 patients reported longstanding pain reduction from the diagnostic SNRB with local anaesthetics. Both patients preferred conservative treatment. One reason for the prolonged pain reduction might be anti-inflammatory effects from the drug [30], another explanation might be a central mode of action as described in studies with similar drugs [2, 16].

Treatment results

Up to 50–70% of the patients treated with transforaminal steroid injections might experience longstanding pain relief and in selected patients transforaminal steroid injections might be an alternative to surgical treatment [29].

In the total series the SNRB results from 11 of the patients did not correlate strictly to either MRI findings or to the neurological deficits/pain distribution (Fig. 2). Eight of these patients were treated directed by the SNRB results and six presented with good/excellent results. In two of these patients (no. 23, 30), the SNRB definitively gave unexpected findings and guided the treatment in a new direction. Among the 13 patients treated at one level, 3 had poor outcome results, 2 treated with steroid injections and 1 treated with surgery. None of the two steroid-treated patients (no. 7 and 13) were interested in further treatment (new injections/surgery). The surgically treated patient (no. 20), had had earlier surgery at an adjacent level and developed a chronically pain syndrome. Also, in this patient, neurological deficit, MRI and SNRB all indicated the same nerve root responsible for the patient’s symptoms. All the patients treated at two levels had good/excellent outcome results.

Fig. 2.

The distribution of the SNRB results from all the 30 patients related to the results from the MRI and the neurological deficits/pain distribution (ND)

Statistical analysis of outcome results from the three different treatment options indicated a less favourable outcome in patients treated conservatively. This is of no surprise, as some of the patients selected to conservative treatment were considered poor candidates for surgical treatment.

Indications for SNRB

In patients with single or multilevel disease and poor correlation between MRI findings and the clinical symptoms or in patients with symptoms of root compression only under provocation, it might be valuable to perform diagnostic blocks prior to treatment decision-making. Also, the attempts to separate cervical radiculopathy from degenerative/inflammatory conditions in the shoulder can sometimes be very difficult and in such patients, SNRB might be a helpful differential diagnostic tool.

Conclusion

Clinical symptoms and signs isolated or combined with MRI findings are not always reliable parameters when selecting pain mediating nerve roots in the multilevel degenerated cervical spine in patients with radiculopathy. According to our results, SNRB seems to be useful for selecting pain mediating nerve roots, when used in the symptomatic two-level degenerated cervical spine in patients with radicular pain.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Liselott Persson, RPT, Department of Neurosurgery, for assistance with the evaluation of the patients.

References

- 1.Akkerveeken van PF. The diagnostic value of nerve root sheath infiltration. Acta Orthop. 1993;64(Suppl 251):61–63. doi: 10.3109/17453679309160120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arner S, Lindblom U, Meyerson BA, Molander C. Prolonged relief of neuralgia after regional anesthetic blocks. A call for further experimental and systematic clinical studies. Pain. 1990;43:287–297. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)90026-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benini A. Clinical features of cervical root compression C5-C8 and their variations. Neuro-Orthopedics. 1987;4:74–88. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benzel EC, Hart BL, Ball PA, Baldwin NG, Orrison WW, Espinosa MC. Magnetic resonance imaging for the evaluation of patients with occult cervical spine injury. J Neurosurg. 1986;85:824–829. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.85.5.0824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boden SD, McCowin PR, Davis DO, Dina TS, Mark AS, Wiesel S. Abnormal magnetic resonance scans of the cervical spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72-A(8):1178–1184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bogduk N, Marsland A. The cervical zygapophyseal joints as a source of neck pain. Spine. 1988;13:610–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brouwers PJ, Kottink EJ, Simon MA, Prevo RL. A spinal artery syndrome after diagnostic blockade of the right C6-nerve root. Pain. 2001;91:397–399. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00437-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burak MO, Lawrence FM. Atypical presentation of C-7 radiculopathy. J Neurosurg (Spine 2) 2003;99:169–171. doi: 10.3171/spi.2003.99.2.0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furman MB, Giovanniello MT, O’Brien EM. Incidence of intravascular penetration in transforaminal cervical epidural steroid injections. Spine. 2003;28:21–25. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200301010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hildebrandt J. Relevance of nerve blocks in treating and diagnosing low back pain: is the quality decisive? Schmerz. 2001;15:474–483. doi: 10.1007/s004820100024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jönsson B, Strömqvist B, Annertz M, Holtås S, Sundén G. Diagnostic lumbar nerve root block. J Spinal Disord Tech. 1988;3:232–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kikuchi S, Macnab P, Moreu P. Localization of the level of symptomatic cervical disc degeneration. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981;2:272–277. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.63B2.7217155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kikuchi S. Anatomical and experimental studies of nerve root infiltration. Nippon Seikeigeka Gakkai Zasshi. 1982;56:605–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kinard RE. Diagnostic spinal injection procedures. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1996;17:15–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinura J. Electrodiagnosis in diseases of nerve and muscle: principles and practise. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: FA Davis company; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koppert W, Ostermeier N, Sittl R, Weidner C, Schmelz M. Low-dose lidocaine reduces secondary hyperalgesia by a central mode of action. Pain. 2000;85:217–224. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00268-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lehto IJ, Tertti MO, Komu ME, Paajanen HEK, Tuominen J, Kormano MJ. Age related MRI changes at 0.1 T in cervical discs in asymptomatic subjects. Neuroradiology. 1994;36:49–53. doi: 10.1007/BF00599196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manifold SG, McCann PD. Cercvical radiculitis and shoulder disorders. Clin Orthop. 1999;368:105–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muhle C, Bischoff L, Weinert D, Lindner V, Falliner A, Maier C. Exacerbated pain in cervical radiculopathy at axial rotation, flexion, extension, and coupled motions of the cervical spine. Evaluation by kinematic magnetic resonance imaging. Invest Radiol. 1998;5:279–288. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199805000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Odom GL, Finney W, Woodhall B. Cervical disc lesions. JAMA. 1958;166:23–28. doi: 10.1001/jama.1958.02990010025006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ongoiba N, Destrieux C, Koumare AK. Anatomical variations of the brachial plexus. Morphologie. 2002;86:31–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perneczky A, Sunder-Plassman M. Intradural variant of cervical nerve root fibres. Potential cause of misinterpreting the segmental location of cervical disc prolapses from clinical evidence. Acta Neurochir. 1980;52:79–83. doi: 10.1007/BF01400951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rozin L, Rozin R, Koehler SA, Shakir A, Ladham S, Barmada M, Dominick J, Wecht CH. Death during transforaminal epidural steroid nerve root block (C7) due to perforation of the left vertebral artery. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2003;24:351–355. doi: 10.1097/00000433-200303000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saal JS (2002) General principles of diagnostic testing as related to painful lumbar spine disorders: a critical appraisal of current diagnostic techniques. Spine 15;27(22):2538–2545 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Sampath P, Bendebba M, Davis J, Ducker D. Outcome in patients with cervical radiculopathy. Spine. 1999;24:591–597. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199903150-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schellhas KP, Smith MD, Gundry CR, Pollei RS. Cervical discogenic pain. Prospective correlation of magnetic resonance imaging and discography in asymptomatic subjects and pain sufferers. Spine. 1996;3:300–312. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199602010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siivola SM, Levoska S, Tervonen O, Ilkko E, Vanharanta H, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S. MRI changes of the cervical spine in asymptomatic and symptomatic young adults. Eur Spine J. 2002;11:358–363. doi: 10.1007/s00586-001-0370-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slipman CW, Plastaras CT, Palmitier RA, Huston CW, Sterenfeld EB. Symptom provocation of fluoroscopically guided cervical nerve root stimulation. Are dynatomal maps identical to dermatomal maps? Spine. 1998;1523:2235–2242. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199810150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slipman CW, Lipetz JS, Jackson HB, Rogers DP, Vresilovic EJ. Therapeutic selective nerve root block in the nonsurgical treatment of atraumatic cervical spondylotic radicular pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:741–746. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(00)90104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yregard L, Cassuto J, Tarnow P, Nilsson U. Influence of local anaesthetics on inflammatory activity postburn. Burns. 2003;29:335–341. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(03)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]