Abstract

The goal of this study was to examine whether adolescent-mother discrepancies in perceptions of the family predict later adolescent externalizing problems and/or whether adolescent externalizing problems predict later adolescent-mother discrepancies in perceptions of the family. In the spring of 2007 (Time 1) and 2008 (Time 2), surveys were administered to 125 15-18 year-old adolescent and their mothers. SEM results indicated that greater discrepancies in adolescent-mother perceptions of the family predicted higher levels of adolescent externalizing symptomatology (as reported by both adolescents and their mothers). In contrast, higher levels of externalizing symptomatology did not predict later discrepancies in adolescent-mother perceptions of the family. These findings suggest that research on adolescent adjustment should not solely rely on perceptions of the adolescent. In addition, the results highlight the importance of taking both directions of effect into consideration when examining the family and adolescent adjustment.

Keywords: adolescence, adolescent-parent relationship, discrepant perceptions, externalizing problems, alcohol use, drug use

During adolescence, family conflict increases and family cohesion decreases (Smetana, Metzger, Gettman, & Campione-Barr, 2006). These changes partially are due to the adolescent’s developing cognitive abilities which allow him/her to question previously held views (Smetana & Villalobos, 2009), including parents’ views. As such, it is typical for adolescents to begin to perceive the family in a more negative light. Importantly, the adolescent’s increasing negative view of the family and subsequent adolescent-parent disagreements may serve key developmental functions; primarily the development of adolescent autonomy and the realignment of family relationships (Steinberg, 1991).

Indeed, some research has supported the tenet that discrepancies in adolescent and parent perceptions are adaptive. For instance, Holmbeck and O’Donnell (1991) found discrepancies in perceptions of autonomy granting in 10- to 18-year old adolescents and their mothers to be associated with an increase in attachment in the adolescent-mother relationship. Discrepancies in adolescents’ and mothers’ perceptions of decision making also were related to lower levels of adolescent internalizing symptomatology. In another study examining 10-14 year-old adolescents with Type I diabetes, Butner and colleagues (Butner et al., 2009) found that discrepancies between adolescents’ and parents’ perceptions of the adolescent’s competence in caring for his/her diabetes were associated with increased levels of adolescent autonomy and parental encouragement of independence.

In contrast, other studies have suggested that discrepancies in perceptions between adolescents and their parents may be related to adolescent maladjustment. For instance, research examining both U.S. and Chinese adolescents has found that discrepancies between adolescents’ and their parents’ perceptions of the family are related to higher levels of anxiety and depression and lower levels of self-esteem (Ohannessian, Lerner, Lerner, & von Eye et al.,1995; Ohannessian, Lerner, Lerner, & von Eye, 2000; Juang, Syed, & Takagi, 2007; Shek, 1998).

Taken together, results from these studies suggest that discrepancies in adolescent-parent perceptions may be essential for the successful mastery of the primary developmental tasks of adolescence (e.g. the development of autonomy and identity) and may be ultimately adaptive for both the adolescent and the family. However, it is important to note that in the short term, differences in perceptions may be associated with increased levels of conflict within the family, which may manifest itself in adolescent problem behaviors.

Limitations of the Literature

Many of the studies examining adolescent-parent discrepancies in perceptions have design limitations and/or are dated. For example, some of the samples assessed have been non-representative (e.g., examining only youth with Type 1 diabetes). In addition, the majority of studies examining discrepancies in adolescent-parent perceptions have focused on young adolescents (e.g., middle school students). Although these studies have been informative, it would be important to examine older adolescents who are more independent from the family given that theories relating to adolescent autonomy suggest that discrepancies in adolescent-perceptions should increase as the adolescent pushes for more autonomy (e.g., Baltes & Silverberg, 1994). If this is the case, as the adolescent gains autonomy within the family and relationships realign, discrepancies in perceptions between adolescents and their parents should decrease. Of note, with few exceptions, most of the studies conducted within this area have been cross-sectional. As such, the direction of influence between adolescent-parent discrepancies in perceptions of the family and adolescent adjustment is not clear. In addition, most previous studies have taken only the adolescent’s perspective into account in relation to indicators of adolescent adjustment; however, parents’ perceptions regarding their adolescent’s adjustment are equally important and may differ from the adolescent’s perceptions (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005; van de Looij-Jansen, Jansen, de Wilde, Donker, & Verhulst, 2011). It also is noteworthy that most studies have focused on discrepancies in perceptions of the family unit (e.g., family cohesion). Less work has examined characteristics of the adolescent-parent relationship, such as adolescent-parent communication. Moreover, no study to date has examined the link between discrepancies in adolescents’ and their parents’ perceptions of the family and adolescent externalizing problems.

Given the limitations of the existing literature, the present study followed a community sample of 125 older adolescents (10th and 11th grade students) and their mothers in order to systematically examine the following research questions: (a) Do discrepancies in adolescents’ and their mothers’ perceptions of the family predict adolescent externalizing problems? and/or (b) Do adolescent externalizing problems predict later discrepancies in adolescents’ and their mothers’ perceptions of the family?

Method

Participants

During the spring of 2007 (Time 1), 10th and 11th grade students attending public high schools in the Mid-Atlantic region of the U.S. (Maryland, Delaware, and Pennsylvania) were invited to participate in the study. The sample included 125 girls (56%) and boys. The mean age of the adolescents was 15.98 (SD=.70, range = 15-18). Seventy-five percent of the adolescents were Caucasian, 13% were African-American, 6% were Hispanic, and 2% were Asian (the rest described themselves as “other”). Most of the adolescents lived with their biological parents – 95% lived with their biological mother and 72% lived with their biological father. The majority of the mothers (96%) and fathers (99%) had graduated from high school.

Procedures

Public high schools that were located within approximately 60 miles of the study site were invited to participate in the larger research project. Seven schools in the Mid-Atlantic region participated. During the spring of 2007, 10th and 11th grade students from these high schools, who provided assent and had parental consent, were given a self-report survey in school by trained research personnel (all of whom were certified with human subjects training). Seventy-one percent of the students attending the participating schools completed the survey. Most of the students that did not participate were absent on the day of data collection. On the day of data collection, only three percent of the students declined participation.

The participants were assured that participation was voluntary, that the data collected were confidential, and that they could withdraw from the study at any time. In addition, they were informed that an active Certificate of Confidentiality from the U.S. government would further protect their privacy. The survey took approximately 40 minutes to complete. Participants were given a movie pass for their participation. All participants were invited to participate again during the following spring (Time 2). The same protocol was used at Time 2. Seventy-eight percent of the students who participated at Time 1 completed the survey again at Time 2 (the attrition rate was 22%). Adolescents who participated at both times of measurement (the longitudinal sample) were compared to those who only participated on one occasion to examine whether they systematically differed from one another. No significant differences for any of the study variables (adolescent-mother discrepancy scores, adolescent substance use, and adolescent externalizing problems) were found between the longitudinal and non-longitudinal subsamples.

Parents of participating adolescent were mailed a packet with an invitation to participate in the study at both times of measurement. The packet included a cover letter inviting them to participate, a consent form, a parent survey, and a prepaid envelope to return the survey. Parents were mailed a $20 gift card upon receipt of their completed survey. The protocol for this study was approved by the University of Delaware’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Family satisfaction

Both adolescents and their mothers completed the Family Satisfaction Scale (FSS; Olson & Wilson, 1989). A representative FSS item is “How satisfied are you with how close you feel to the rest of your family?” Participants responded on a scale ranging from 1 = dissatisfied to 5 = extremely satisfied. Separate family satisfaction scores were calculated for adolescents and their mothers. In the present study, Cronbach alpha coefficients were .90 at Time 1 and .91 at Time 2 for the adolescents’ reports, and .83 at Time 1 and .89 at Time 2 for the mothers’ reports.

Adolescent-mother communication

The Parent-Adolescent Communication Scale (PACS; Barnes & Olson, 2003) was used to measure communication between adolescents and their mothers. This 20-item measure includes two subscales – open family communication and problems in communication. Adolescents and their mothers responded to the same items in regard to their communication with one another. A sample item is “There are topics I avoid discussing with my mother/child”. Participants responded on a scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Separate scale scores were calculated for adolescents and their mothers. In the present sample, Cronbach alpha coefficients ranged from .78 to .93 for the adolescents and .79 to .89 for the mothers across Time 1 and Time 2.

Adolescent reports of their own substance use

The adolescents were asked to report how much, on the average day, they usually drank (beer, wine, or liquor) in the last six months (separate questions were used for beer, wine, and liquor). The response scale ranged from 0 = none to 9 = more than 8 drinks. They also were asked to report how often they usually had a drink (beer, wine, or liquor) in the last six months on a scale ranging from 0 = never to 7 = every day. Based on this information, a total alcohol quantity x frequency score was calculated. In addition, the adolescents were asked, in reference to the last six months, how many times they had six or more drinks and how frequently they had used marijuana, sedatives, stimulants, inhalants, hallucinogens, cocaine or crack, and opiates (non-medical use only). The drug response scale ranged from 0 = no use to 7 = every day. A total drug use score was calculated by summing the scores of the different types of drugs. Because the substance use scores were skewed, the logarithmic transformation of these scores was used.

Mothers’ reports of their adolescent’s externalizing problems

The 113-item Child Behavior Checklist (CBC; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) was used to obtain mothers’ reports of their child’s problem behaviors. When completing the CBC, parents are presented with a list of problems and are asked to state whether each problem is 0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, or 2 = very true or often true for their child. The CBC scales used in this study were aggressive behavior (α = .85) and rule breaking behavior (α = .81).

Results

Discrepancy scores were calculated by subtracting the adolescent score from the mother score for the family measures. Means and (ranges) for the discrepancy scores at Time 1 and Time 2 respectively were as follows: 1.21 (−16 to +21) and .78 (−15 to +22) for family satisfaction, 3.27 (−16 to +23) and 2.90 (−25 to +30) for open communication, and −5.81 (−34 to +20) and −5.09 (−30 to +19) for communication problems. In order to aid in interpretation, the absolute values of the discrepancy scores were used.

Structural equation modeling was conducted to examine whether adolescent-mother discrepancies in perceptions of the family predicted adolescent externalizing problems one year later and/or whether externalizing problems predicted discrepancies in adolescent-mother perceptions of family functioning one year later. The SEM analyses were carried out in three steps. Model 1 tested the specified structural model. Model 2 only included significant paths from Model 1. Model 3, the final model, was identical to Model 2, with the exception that the disturbance terms were allowed to be correlated.

Do Discrepancies in Perceptions of the Family Predict Adolescent Externalizing Problems?

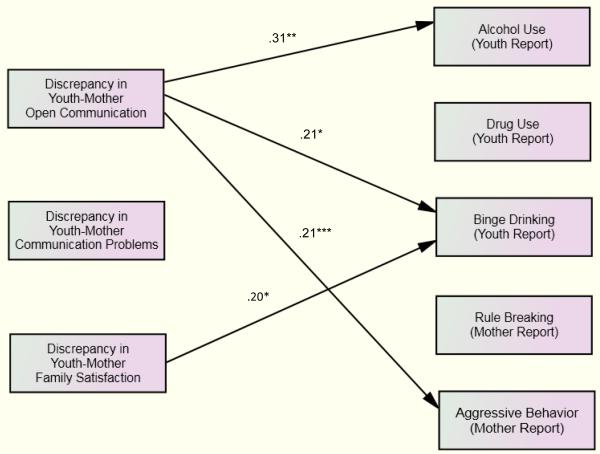

The final model predicting externalizing problems from adolescent-mother discrepancies in family perceptions fit the data well (X2(10) = 15.78, p = .11; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .02). As shown in Figure 1, discrepancies in adolescent-mother perceptions of family satisfaction predicted adolescent reports of their binge drinking (β = .20, p<.05), indicating that adolescents with more discrepant perceptions of family satisfaction with their mother reported more frequent binge drinking. In addition, discrepancies in adolescent-mother perceptions of open communication predicted adolescent reports of their own alcohol use (β = .31, p<.01) and binge drinking (β = .21, p<.05) and mothers’ reports of adolescent aggressive behavior (β = .21, p<.001). These results indicated that greater discrepancies in adolescent-mother perceptions of communication led to higher levels of adolescent substance use and aggressive behavior one year later.

Figure 1.

Family satisfaction predicting adolescent externalizing problems. Standardized regression coefficients are presented. For ease of interpretation, only significant paths are shown. Disturbance terms and covariances are not displayed.

*p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001.

Of note, the SEM analyses examined the relationship between the magnitude of discrepancies in perceptions of family functioning and adolescent internalizing problems. However, they did not provide information relating to the direction of the discrepancy. Therefore, post-hoc Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) models were conducted for the significant paths to examine the direction of the discrepancy. For the ANOVA analyses, the original discrepancy score was trichotomized (adolescents had a more negative view, mothers had a more negative view, adolescents and mothers had similar views). The trichotomized discrepancy was the design factor and externalizing problems were the dependent variables. Post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparison tests were used to determine whether the group means significantly differed from one another. None of the ANOVAs were significant, indicating that discrepant adolescent-mother perceptions of the family were related to adolescent externalizing problems, regardless of the direction of the discrepancy.

Do Adolescent Externalizing Problems Predict Discrepancies in Perceptions of the Family?

The final model predicting adolescent-mother discrepancies in family perceptions from externalizing problems also provided a good fit to the data (X2(15)=12.26, p=.66; CFI=1.00; RMSEA=.00). However, in this model, none of the externalizing problems predicted discrepancies in perceptions of family satisfaction, open communication, or communication problems.

Discussion

In this study, discrepancies in adolescents’ and their mothers’ perceptions of the family predicted both adolescent and mother reports of adolescent externalizing problems one year later. These findings indicate that when the adolescent’s perceptions of the family do not concur with their mother’s perceptions of the family, the adolescent subsequently is more likely to drink more heavily and to behave more aggressively. Results from this study are consistent with the handful of other studies examining discrepancies in adolescents’ and their parents’ perceptions of the family. For instance, Juang and colleagues (Juang, Syed, & Takagi, 2007) found that more discrepant perceptions between adolescents’ and their parents’ perceptions of parental control were related to more depressive symptoms in their sample of 166 9th and 10th-grade Chinese American families. Research examining younger adolescents has yielded a similar pattern of results. For example, Ohannessian et al. (1995; 2000) found discrepancies in perceptions of the family between early adolescents (6th and 7th grade students) and their parents to predict higher levels of adolescent depression and anxiety symptomatology, but lower levels of self-competence. Likewise, in a longitudinal study focusing on 378 Hong Kong Chinese early adolescents and their parents, Shek (1998) found discrepancies in perceptions of family functioning between adolescents and their parents to be associated with a number of negative adjustment indicators for adolescents (e.g., hopelessness, lower self-esteem, higher levels of psychiatric morbidity). Results from these studies suggest that discrepancies in adolescents’ and their parents’ perceptions of the family may contribute to adolescent problem behaviors.

A strength of the present study is that the design was longitudinal. As such, both directions of effect between discrepancies in adolescent-parent perceptions and adolescent adjustment could be assessed. When the opposite direction of effect was examined – that is, whether adolescent externalizing problems predict discrepancies in adolescent-parent perceptions of the family, adolescent externalizing problems did not predict discrepancies in adolescents’ and their mothers’ perceptions. Results from this study support the tenet that discrepancies in perceptions between adolescents and their parents may lead to adolescent problem behaviors, but adolescent problem behaviors are not likely to lead to more discrepant perceptions between adolescents and their parents.

As noted, prior research has suggested that discrepancies in adolescent-parent perceptions may be essential for the successful mastery of the primary developmental tasks of adolescence (e.g. the development of autonomy and identity) and may be ultimately adaptive for both the adolescent and the family. During adolescence, the family may be unsettled as adolescent-parent relationships are renegotiated and the adolescent becomes more autonomous (Holmbeck & O’Donnell, 1991; Montemayor & Flannery, 1991; Shek, 2002; Steinberg, 1990, 1991). During the process of relationship realignment, conflict and disagreements between adolescents and their parents are likely to occur. Such disagreements may manifest themselves in discrepant perceptions between adolescents and their parents, which may lead to problem behaviors, including externalizing problems for some adolescents. Importantly, these problems may not be persistent and may reflect temporary perturbations as adolescents and their parents renegotiate their changing roles in the family. Long-term longitudinal research is needed to shed light on the duration of adolescent problem behaviors that may result from discrepant adolescent-parent perceptions.

Although this study contributes to the extant literature, caveats should be noted. First, consistent with most studies examining adolescents and their parents, parent data relied on mothers’ reports. Of note, fathers were invited to participate; however, the response rate from fathers was relatively low (n = 67 at Time 1). Therefore, only mothers were included. Although differences have been observed in adolescent-mother versus adolescent-father relationships (Smetana et al., 2006), mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of the family have been found to be highly correlated with one another (Butner et al., 2009; Ohannessian et al., 2000). A related limitation is that only mother reports of externalizing problems were assessed. It would be important for future research to include adolescent reports of their own externalizing problems as well.

Despite these limitations, the present study extends the literature in many respects. As noted, research examining discrepant perceptions between adolescents and their parents is scare. Much of the research available also is characterized by design problems, including the use of non-representative samples. Importantly, the sample for the present study was drawn from the community. The sample also included older adolescents (an overlooked group). In addition, cross-informant data were used. Most prior studies have taken only the adolescent’s perspective into account in regard to indicators of adolescent adjustment; however, parents’ perceptions regarding their adolescent’s adjustment are equally important and may differ from the adolescent’s perceptions (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005; van de Looij-Jansen et al., 2011). An additional strength of the study was the longitudinal design, which allowed for the examination of both directions of influence, which is essential according to contemporary models of human development (e.g., relational developmental systems theories; Lerner, in press; Lerner & Overton, 2008). In sum, results from this study clearly highlight the importance of taking both the perceptions of the adolescent and their parents into account and considering both directions of influence when examining family functioning and adolescent psychological adjustment.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grant K01-AA015059. The study would not have been possible without the gracious participation of the high schools and adolescents attending those schools. Many thanks to The Adolescent Adjustment Project (AAP) staff who kept the project running: Kelly Cheeseman, Alyson Cavanaugh, Ashley Malooly, Lisa Fong, Sara Bergamo, Elizabeth Lewis, Ashley Ings, and Juliet Bradley.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-age forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Adolescent, & Families; Burlington, VT: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes MM, Silverberg SB. The dynamics between dependency and autonomy: Illustrations across the life span. In: Featherman DL, Lerner RM, Perlmutter M, editors. Life-span development and behavior. Vol. 12. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; Hillsdale, NJ: 1994. pp. 41–90. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes H, Olson DH. Parent-Adolescent Communication Scale. Life Innovations, Inc.; Minneapolis: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ. The social brain in adolescence. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2008;9(4):267–277. doi: 10.1038/nrn2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butner J, Berg CA, Osborn P, Butler JM, Godri C, Fortenberry KT, Barach I, Le H, Wiebe DJ. Parent-adolescent discrepancies in adolescents’ competence and the balance of adolescent autonomy and adolescent and parent well-being in the context of Type 1 diabetes. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(3):835–849. doi: 10.1037/a0015363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131(4):483–509. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juang LP, Syed M, Takagi M. Intergenerational discrepancies of parental control among Chinese American families: Links to family conflict and adolescent depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30(6):965–975. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM. Developmental science: Past, present, and future. International Journal of Developmental Science. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM, Overton WF. Exemplifying the integrations of the relational developmental system: Synthesizing theory, research, and application to promote positive development and social justice. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2008;23(3):245–255. [Google Scholar]

- Ohannessian CM, Lerner RM, Lerner JV, von Eye A. Discrepancies in adolescents’ and parents’ perceptions of family functioning and adolescent emotional adjustment. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1995;15(4):490–516. [Google Scholar]

- Ohannessian CM, Lerner RM, Lerner JV, von Eye A. Adolescent-parent discrepancies in perceptions of family functioning and early adolescent self-competence. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2000;24(3):362–372. [Google Scholar]

- Olson DH, Wilson M. Family satisfaction. In: Olson DH, McCubbin HI, editors. Family inventories. Family Social Science, University of Minnesota; St. Paul: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Shek DTL. A longitudinal study of Hong Kong adolescents’ and parents’ perceptions of family functioning and well-being. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development. 1998;159(4):389–403. doi: 10.1080/00221329809596160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Metzger A, Gettman DC, Campione-Barr N. Disclosure and secrecy in adolescent-parent relationships. Child Development. 2006;77(1):201–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana J, Villalobos M. Social cognitive development in adolescence. In: Lerner R, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 3rd ed Vol. 1. Wiley; New York: 2009. pp. 187–228. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Parent-adolescent relations. In: Lerner RM, Petersen AC, Brooks-Gunn J, editors. Encyclopedia of adolescence. Garland; New York: 1991. pp. 724–728. [Google Scholar]

- van de Looij-Jansen PM, Jansen W, de Wilde EJ, Donker MCH, Verhulst FC. Discrepancies between parent-child reports of internalizing problems among preadolescent children: Relationships with gender, ethnic background, and future internalizing problems. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2011;31(3):443–462. [Google Scholar]