Abstract

The study evaluated trait associations with common Disruptive Behavior Disorders (DBD), Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), during an understudied developmental period: Preschool. Participants were 109 children ages 3 to 6 and their families. DBD symptoms were available via parent and teacher/caregiver report on the Disruptive Behavior Rating Scale. Traits were measured using observational coding paradigms, and parent and examiner report on the Child Behavior Questionnaire and the California Q-Sort. The DBD groups exhibited significantly higher negative affect, higher surgency, and lower effortful control. Negative affect was associated with most DBD symptom domains; surgency and reactive control were associated with hyperactivity-impulsivity; and effortful control was associated with ADHD and inattention. Interactive effects between effortful control and negative affect and curvilinear associations of reactive control with DBD symptoms were evident. Temperament trait associations with DBD during preschool are similar to those seen during middle childhood. Extreme levels of temperament traits are associated with DBD as early as preschool.

Keywords: preschool children, behavior problems, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), temperament

1. INTRODUCTION

Disruptive Behaviors Disorders (DBD), including Oppositional-Defiant Disorder (ODD) and arguably Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), are common and highly impairing childhood behavioral disorders that are often comorbid (Angold, Costello, & Erkanli, 1999; Pelham, Foster, & Robb, 2007). Recent work indicates that ODD and ADHD can be identified as early as preschool (Keenan & Wakschlag, 2002; Task Force, 2003; Wakschlag, Tolan, & Leventhal, 2010). However, examination of temperament trait associations with DBD during preschool remains limited. It is important to examine associations between DBD and temperament traits during preschool to provide further external validation of preschool DBD diagnosis (Cantwell, 1992; Robins & Guze, 1970). Extreme levels of temperament traits might have utility for identifying children at risk for early DBD since temperament traits can be measured earlier than DBD.

Temperament traits are constitutionally-based individual differences in reactivity and self-regulation (Rothbart & Posner, 2006). There are many models of temperament available. However, most of these models converge on the importance of three specific traits: negative affect, surgency, and effortful control (Eisenberg et al., 1996; Rothbart, 1989). Negative affect is defined by a high level of negative emotions, including anger, sadness, and fear. Surgency refers to high positive emotions related to approach or social behavior. Effortful control is thoughtful, deliberate forms of regulation (Rothbart, Ahadi, & Evans, 2000). A fourth dimension of temperament that may also be important in relation to DBD and ADHD is reactive control, or affectively-driven, reflexive forms of regulation (Valiente et al., 2003). Temperament traits may predispose individuals to psychopathology, share common etiological factors with psychopathology, and/or lie on the same continuum as psychopathology (Shiner & Caspi, 2003; Tackett, 2006). Regardless of the exact nature of trait-psychopathology associations, traits may be useful as early markers of psychopathology. In line with this idea, temperament traits such as low effortful control and high negative emotionality and approach exhibit well-replicated associations with DBD, including ADHD, by middle childhood (e.g., De Pauw & Mervielde, 2011; Huey & Weisz, 1997; Olson et al., 2002; Shaw et al., 1994).

Temperament traits exhibit differential associations with developmental psychopathology (Martel, 2009; Nigg, 2006; Tackett, 2006). High negative affect increases risk for psychopathology in general, including DBD and ADHD (Lahey, 2009). However, high surgency and low reactive control may be specifically associated with ADHD hyperactivity-impulsivity, and low effortful control may be specifically associated with ADHD inattention (Martel & Nigg, 2006; Parker, Majeski, & Collin, 2004), in line with recent multiple pathway models of DBD and ADHD (e.g., Nigg et al., 2004; Sonuga-Barke et al., 2010). Further, complex associations between traits and developmental psychopathology are apparent. For example, effortful control interacts with negative affect to predict externalizing problems such that children characterized by low effortful control in conjunction with high negative emotionality are at particular risk for DBD (Martel & Nigg, 2006; Muris & Ollendick, 2005). Reactive control exhibits curvilinear associations with psychopathology-related outcomes; both low and high reactive control may be maladaptive since they lead to under- and over-control respectively (Eisenberg et al., 2003; Martel et al., 2007).

What remains unknown is whether preschool DBD exhibits similar associations with temperament traits as childhood DBD, the goal of the present study. It was hypothesized that high negative affect, high surgency, and low effortful and reactive control would be associated with preschool DBD symptoms (similar to childhood DBD). Specificity of associations were predicted such that high negative affect would be associated more generally with DBD symptomatology, while high surgency and low effortful control would exhibit more specific associations with hyperactivity-impulsivity and inattention, respectively. Exploratory analyses evaluated whether negative affect and effortful control would interact to predict DBD symptoms and that reactive control would exhibit curvilinear associations with DBD.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

2.1.1. Overview

Participants were 109 preschoolers between ages three and six (M=4.77 years, SD=1.11) and their primary caregivers. Sixty-four percent of the sample was male; 33% of the sample was ethnic minority (see Table 1). Parental educational level ranged from unemployed to highly skilled professionals, with incomes ranging from below $20,000 to above $100,000 annually. Based on multistage and comprehensive diagnostic screening procedures, preschoolers were recruited into two groups: DBD (n=79), subdivided into ADHD-only (n=18), ODD-only (n=18), and ADHD+ODD (n=43); and non-DBD children (n=30). The non-DBD group included preschoolers with subthreshold symptoms to provide a more continuous measure of ADHD and ODD symptoms and symptom counts were the focus of analyses, consistent with research suggesting that ADHD and ODD may be better captured by continuous dimensions than categorical diagnosis (Haslam et al., 2006; Levy et al., 1997) and to be sensitive to the young age of the sample.

Table 1.

Demographic and Descriptive Information on Sample

| Control (c) n=30 |

ODD-only (o) n=18 |

ADHD-only (a) n=18 |

ODD+ADHD(oa) n=43 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | ||

| Age* | 4.28 | (1.07) | 5.07 | (1.19) | 5.03 | (.95) | 4.89 | (1.08) | |

| Boys n(%) | 14 | (46.7) | 10 | (55.6) | 13 | (72.2) | 27 | (62.8) | |

| Ethnic Minority n(%)* | 7 | (23.3) | 2 | (11.2) | 10 | (55.6) | 17 | (39.5) | |

| Family Income (mode)* | 1, 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| ODD symptoms (P)** | 2.971,2 | (3.08) | 10.01,3 | (6.02) | 5.833,4 | (3.28) | 11.602,4 | (7.24) | c<a<o<oa |

| ADHD symptoms (P)** | 8.601,2,3 | (6.86) | 19.731,4 | (12.98) | 26.722,5 | (9.09) | 35.263,4,5 | (13.5) | c<o<a<oa |

| Inattention** | 3.771,2,3 | (3.87) | 8.931,4 | (6.77) | 11.392,5 | (5.88) | 16.03,4,5 | (7.29) | c<o<a<oa |

| Hyper-Impulsive** | 4.831,2,3 | (3.76) | 10.81,4,5 | (6.62) | 15.332,4,6 | (5.43) | 19.263,5,6 | (7.04) | c<o<a<oa |

| ODD symptoms (T)** | 2.641 | (3.63) | 3.802 | (3.68) | 5.173 | (3.97) | 11.841,2,3 | (6.68) | c, o, a<oa |

| ADHD symptoms (T)** | 10.081,2 | (9.11) | 7.783,4 | (7.97) | 37.601,3 | (10.16) | 36.322,4 | (8.51) | c, o<a, oa |

| Inattention** | 4.151,2 | (4.26) | 3.893,4 | (3.95) | 23.201,3,5 | (2.95) | 17.952,4,5 | (5.75) | c, o<a, oa |

| Hyper-Impulsive** | 5.641,2 | (5.47) | 3.893,4 | (4.17) | 14.671,3 | (7.99) | 18.372,4 | (5.41) | c, o<a, oa |

| Negative Affect** | 3.451,2,3 | (.76) | 4.181,4 | (.72) | 4.602 | (.81) | 4.713,4 | (.98) | c<o,a<oa |

| Surgency* | 4.501 | (.77) | 4.492 | (.99) | 4.533 | (1.10) | 5.141,2,3 | (.94) | c, o, a<oa |

| Effortful Control* | 5.241 | (.76) | 4.73 | (1.00) | 4.76 | (.69) | 4.651 | (.95) | oa<c |

| Reactive Control | 4.92 | (1.11) | 4.86 | (.89) | 4.81 | (1.18) | 4.31 | (1.48) | |

| Face & Body Anger | 3.82 | (3.64) | 2.73 | (3.47) | 3.53 | (4.66) | 3.03 | (3.93) | |

| Verbal Anger | 1.72 | (2.32) | 1.60 | (2.41) | 2.23 | (4.10) | 2.27 | (2.33) | |

| Face & Body Sadness | .58 | (1.02) | 1.13 | (2.00) | .27 | (.59) | 1.43 | (2.74) | |

| Verbal Sadness* | .681 | (.89) | 1.631,2,3 | (1.86) | .602 | (.99) | .573 | (.94) | c, a,oa<o |

| Positive Motor Acts | 10.40 | (2.54) | 8.46 | (3.62) | 10.07 | (3.03) | 9.24 | (3.21) | |

| Positive Vocals | 2.40 | (3.58) | 2.08 | (2.96) | 1.50 | (3.18) | 2.34 | (3.06) | |

| Gift Delay Peek* | 3.11 | (1.88) | 4.231 | (1.36) | 3.20 | (1.82) | 2.861 | (1.66) | oa<o |

| Gift Delay Touch | 3.47 | (1.02) | 3.46 | (.66) | 3.33 | (.72) | 3.28 | (.65) | |

Note.

p<.05,

p<.01.

Subgroup differences based on chi-square or ANOVA with follow-up LSD post hoc tests indicated with like superscripts. Family income modes: 0=annual income less than $20,000, 1=between $20,000 and $40,000, 2=between $40,000 and $60,000, 3=between $60,000 and $80,000, 4=between $80,000 and $100,000, and 5=over $100,000 annually. (P)=Parent report. (T)=Teacher report. Gift Delay Peek and Touch=high scores indicate better control.

2.1.2. Recruitment and Identification

Participants were recruited from the community through direct mailings, postings, advertisements, and flyers, designed to over-recruit clinical cases. A telephone screening was conducted to rule out children prescribed psychotropic medication (e.g., antidepressants) or children with neurological impairments, mental retardation, autism spectrum disorders, psychosis, seizure history, head injury with loss of consciousness, or other major medical conditions. All families screened into the study completed written and verbal informed consent procedures consistent with the Institutional Review Board, the National Institute of Mental Health, and APA guidelines.

Parents and preschoolers attended a campus laboratory visit. Diagnostic information was collected via parent and teacher/caregiver ratings. Parents completed the Kiddie Disruptive Behavior Disorders Schedule (K-DBDS: Leblanc et al., 2008) administered by a trained graduate student clinician. The K-DBDS demonstrates high test-retest reliability and high inter-rater reliability in the preschool population (LeBlanc et al., 2008). In the current study, clinician agreement was adequate for ODD and ADHD symptoms (r=.99, p<.001, r=1.00, p<.001, respectively).

Families were mailed teacher/caregiver questionnaires prior to the laboratory visit and instructed to provide the questionnaires to children’s teacher and/or daycare provider/babysitter (67% teachers, with most of the remaining questionnaires completed by daycare providers or babysitters). This other report was available on only 50% of participating families due to a poor response rate (response rate did not differ based on child DBD diagnostic group; χ2[3]=.59, p=.9).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Symptom Counts

Parent and teacher/caregiver reports on symptoms were available via the Disruptive Behavior Rating Scale (DBRS: Barkley & Murphy, 2006), which assesses symptoms using a 0 to 3 scale. The DBRS has high internal consistency ranging from .78 to .96 in the preschool age range (Pelletier, Collett, Gimple, & Cowley, 2006). Ratings were summed within each diagnostic subdomain (i.e., ODD, ADHD, inattention, etc.) to obtain total symptom counts. All scales for parent and teacher/caregiver report on the DBRS had high internal reliability (all alphas > .92) in the current sample.

2.2.2. Temperament and Personality Traits: Questionnaires

Parents completed the very short form of the Child Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey & Fisher, 2001; Putnam & Rothbart, 2006). Negative affect, surgency, and effortful control were measured using the scales suggested byRothbart et al. (2001). Composite scale scores were generated by reverse-scoring selected items and computing the average. The scales had acceptable internal reliability coefficients of .70 or above in the current sample. To measure reactive control, an examiner completed the California Child Q-Sort (CCQ; Block, 2008; Block & Block, 1980). The CCQ is a typical Q-Sort consisting of 100 cards which must be placed in a forced-choice, nine-category, rectangular distribution. A scale developed by Eisenberg and colleagues (1996; 2003) was used. The composite scale score was generated by reverse-scoring selected items and computing the average. Reliability was .86. Items on all temperament traits scales were examined for overlap with ODD and ADHD symptoms. Two items on the effortful control scale and five items on the reactive control scale were judged to overlap with ADHD items. Scale reliabilities remained adequate when overlapping items were deleted (α=.66 for effortful control and α=.81 for reactive control).

2.2.3. Temperament Traits: Observation

Select paradigms from the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (LABTAB; Goldsmith et al., 1999; Kochanska, Murray, & Harlan, 2000) provided observational ratings of preschool temperament traits. Negative affect (i.e., “perfect circle”), surgency (i.e., “bubble gun”), and effortful control (i.e., “gift delay”) paradigms were used in the present study (see Goldsmith et al., 1999). During specified increments, facial, body, and verbal expressions of negative affect, surgency, and/or effortful control were tallied to create composite variables. Reliability was acceptable for all observational coding composites utilized in the current study (all kappas >.78). Higher scores denote higher traits.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Missingness was minimal in the current study, with the exception of teacher ratings on the DBRS. The missingness and nonnormality of data were addressed using robust full information maximum likelihood estimation (i.e., direct fitting) in Mplus (Múthen & Múthen, 1998–2008), a method of directly fitting models to raw data without imputing data (McCartney et al., 2006). Main analyses were conducted in Mplus using bivariate correlations and a series of multivariate linear regressions. Examination of main effects and interactive effects was conducted using hierarchical entry procedures (Holmbeck, 1997). Power analysis indicated that statistical power was adequate (.80) to detect a medium-size effect (r = .25).

3. RESULTS

As shown in Table 1, mean levels of all questionnaire-rated traits except reactive control were significantly different across diagnostic groups (all p<.05; see Table 1) in the expected direction.

3.1. Associations Between Temperament Traits and DBD Symptom Domains

Bivariate correlations were conducted between temperament traits and DBD symptom domains. As shown in Table 2, high negative affect was significantly associated with parent- and teacher-rated ODD, ADHD, inattentive, and hyperactive-impulsive symptoms (r=.38–.65, all p<.01; medium effect size [ES]). High surgency was significantly associated with increased parent- and teacher-report ODD symptoms (r=.33–.41, all p<.01; medium ES) and with parent-rated total ADHD, inattentive, and hyperactive-impulsive symptoms (r=.34–.51, all p<.01; medium ES), but not teacher-rated ADHD, inattentive, or hyperactive-impulsive symptoms (r=.05–.20, all p>.05; small ES). Low effortful control was significantly associated with parent-rated total ADHD, inattentive, and hyperactive-impulsive ADHD symptoms (r=−.21–−.24, all p<.05; medium ES), but not with parent-rated ODD symptoms or teacher-rated DBD symptoms (r=−.13–.26, all p>.05; small ES). Lower reactive control (rated by examiners) was significantly associated with parent-rated ODD, total ADHD, inattentive, and hyperactive-impulsive symptoms (r=−.23–−.31, all p<.05; medium ES), but not with teacher-rated DBD symptoms (r=−.03–−.22, all p>.05; small to medium ES). None of the observational measures of temperament traits were significantly associated with DBD symptoms with the exception of low effortful control which was significantly associated with parent- and teacher-rated DBD symptoms (r=−.24–−.55, p<.05; medium ES). Thus, high negative affect and low effortful and reactive control appeared associated with DBD symptoms, even when utilizing different raters or observational measures for trait and symptom ratings to correct for shared source variance. However, high surgency was associated with ODD symptoms, as rated by parents and teachers, but with ADHD symptom domains, only when rated by parents.

Table 2.

Correlations Between Temperament Traits and DBD Symptoms

|

ODD |

ADHD |

Inattention |

Hyperactivity/ Impulsivity |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | (T) | P | (T) | P | (T) | P | (T) | |

| NA | .48** | (.38)** | .51** | (.53)** | .42** | (.55)** | .55** | (.45)** |

| Surgency | .33** | (.41)** | .44** | (.15) | .34** | (.08) | .51** | (.20) |

| EC | −.13 | (−.26) | −.23* | (−.23) | −.24* | (−.19) | −.21* | (−.24) |

| RC | −.27** | (−.21) | −.28** | (−.11) | −.23* | (−.03) | −.31** | (−.22) |

| F/B Anger | .10 | (−.12) | −.02 | (−.13) | −.03 | (−.19) | −.004 | (−.05) |

| V Anger | .16 | (.15) | .14 | (.12) | .12 | (.04) | .14 | (.20) |

| F/B Sadness | −.01 | (−.05) | −.08 | (−13) | −.06 | (.15) | −.10 | (.09) |

| V Sadness | −.04 | (−.10) | −.16 | (−.18) | −.12 | (−.12) | −.18 | (−.23) |

| PMA | −.04 | (.01) | −.08 | (.23) | −.05 | (.32) | −.09 | (.06) |

| PV | .12 | (.09) | .11 | (−.01) | .10 | (−.06) | .11 | (.04) |

| GD Peek | −.04 | (−.44)** | −.08 | (−.43)* | −.03 | (−.23) | −.13 | (−.55)** |

| GD Touch | −.24* | (−.49)** | −.30* | (−.38)* | −.27* | (−.33) | −.30** | (−.37)* |

Note.

p<.05.

p<.01.

NA=Negative Affect. EC=Effortful Control. RC=Reactive Control. F/B Anger=Face & Body Anger. V Anger=Verbal Anger. F/B Sadness=Face & Body Sadness. V Sadness= Verbal Sadness. P M A=Positive Motor Acts. P V=Positive Vocals. GD Peek= Gift Delay Peek. GD Touch=Gift Delay Touch. P=Parent-report symptoms. (T)=Teacher-report symptoms.

3.2. Specificity of Associations Between Traits and Parent-Rated DBD

Since parent-rated temperament traits exhibited significant associations with most DBD symptom domains, specificity of associations between temperament traits and parent-rated DBD symptom domains was assessed via a set of regression analyses in which traits were the dependent variables and parent-rated DBD symptom domains were simultaneously entered as independent variables to partial out their shared covariance (Table 3). When symptom domains were entered simultaneously as predictors, high negative affect was significantly associated with ODD symptoms (β=.26, p<.05) and ADHD symptoms (β=.34, p<.01). However, when examining ADHD symptom domains, high negative affect was only significantly associated with hyperactivity-impulsivity (β=.68, p<.01), but not with inattention (β=−.15, p>.05). High surgency was significantly associated with ADHD symptoms (β=.40, p<.01), but not with ODD symptoms (β=.07, p>.05). When examining specific ADHD symptom domains, surgency was significantly positively associated with hyperactivity-impulsivity (β=.76, p<.01), but significantly negatively associated with inattention (β=−.30, p<.05). Low effortful control was significantly associated with ADHD symptoms (β=−.26, p<.05), but not ODD symptoms (β=.04, p>.05). When examining specific ADHD symptom domains, low effortful control was not significantly associated with either symptom domain (β=−.21 for inattention; β=−.15 for hyperactivity-impulsivity, both p>.05). Reactive control was not significantly associated with ODD or ADHD symptoms (β=−.15 for ODD; β=.−.18 for ADHD, both p>.05). When examining ADHD symptom domains, low reactive control was associated with high hyperactivity-impulsivity (β=−.43, p<.05), but not inattention (β=.14, p>.05). Thus, while negative affect appeared associated with DBD in general, effortful control appeared associated primarily with ADHD, and surgency and reactive control appeared most associated with hyperactivity-impulsivity, although it should be noted that these differences were not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Specificity of Associations Between Temperament Traits and DBD Symptoms

| DV | Negative Affect |

Surgency | Effortful Control |

Reactive Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV | ||||

| ODD Symptoms | .26* | .07 | .04 | −.15 |

| ADHD Symptoms | .34* | .40** | −.26* | −.18 |

| Inattention | −.15 | −.30* | −.21 | .14 |

| Hyperactivity- Impulsivity |

.68** | .76** | −.15 | −.43* |

Note.

p<.05.

p<.01.

3.3. Interactive Effects Between Negative Affect and Effortful Control and Curvilinear Associations of Reactive Control

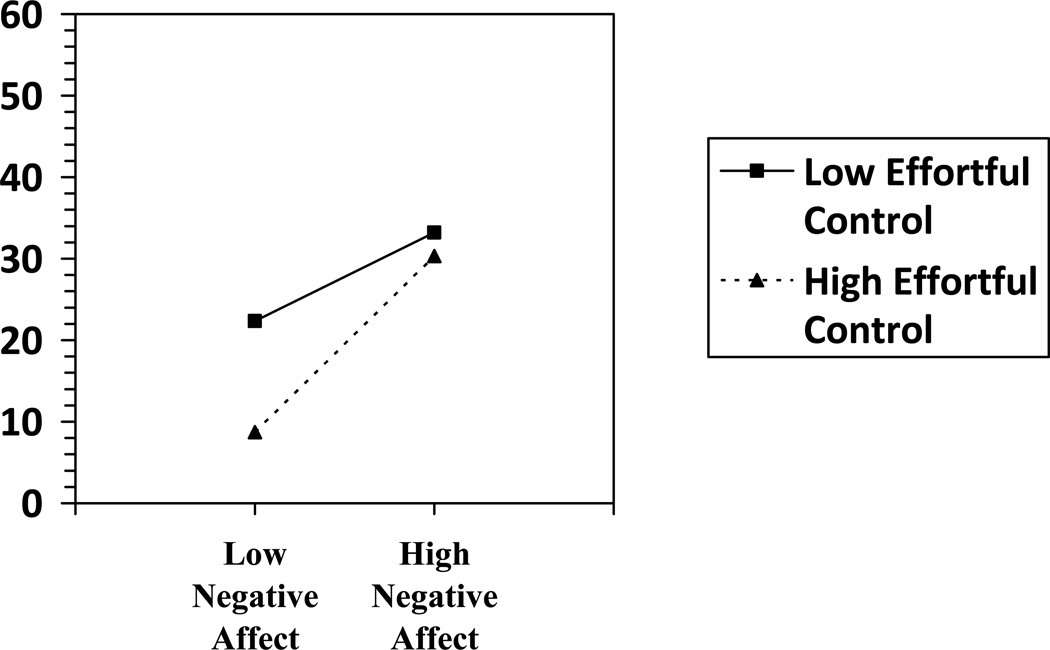

Two hierarchical regression analyses were conducted in order to examine interactive effects between negative affect and effortful control in relation to child DBD symptoms. Negative affect and effortful control did not significantly interact to predict parent- or teacher-rated ODD symptoms (p≥.35; ΔR2=.007–.02). Negative affect and effortful control significantly interacted to predict parent-rated ADHD symptoms (p=.04; ΔR2=.03), but not teacher-rated ADHD symptoms (p=.71; ΔR2=.003). Low effortful control was related to higher parent-rated ADHD symptoms, regardless of the level of negative affect (Figure 1), seeming to be a primary pathway of ADHD. However, when effortful control was high, higher negative affect was associated with increased ADHD symptoms, appearing to be a secondary pathway to ADHD.

Figure 1.

Negative Affect and Effortful Control Interact to Predict ADHD Symptoms

Two hierarchical regressions were conducted to examine curvilinear associations of reactive control with ODD and ADHD symptoms. Reactive control was curvilinearly associated with parent-rated ODD and ADHD symptoms (p=.01; R2=.1 for both), but not teacher-rated ODD or ADHD symptoms (p≥.23; R2=.03–.09). Both high and low levels of reactive were associated with increased parent-rated DBD symptoms.

4. DISCUSSION

Similar to associations in later childhood, preschoolers with DBD, particularly those with ODD+ADHD, appear characterized by increased negative affect and surgency and lower levels of effortful control than children without DBD. These findings provide further external validation of diagnosis of DBD during preschool (Cantwell, 1992; Robins & Guze, 1970), as well as some support for vulnerability or spectrum conceptualizations of trait-psychopathology associations (vs. scar models which suggest that psychopathology leads to changes in traits). Of course, this study cannot definitely rule out other models of trait-psychopathology associations (Shiner & Caspi, 2003; Tackett, 2006).

Rater effects were notable. Although negative affect, surgency, effortful control, and reactive control all appear to be associated with DBD and survived correction for shared source variance, associations between traits and DBD symptoms did differ somewhat based on rater, possibly due to rater sensitivity to situational demands on the child (Majdandzic & van den Boom, 2007; Mischel & Shoda, 1995). This work suggests that different raters provide equally valid information on traits and symptoms, as they are differentially manifested in specific contexts (Bartels et al., 2004; Bird, Gould, & Staghezza, 1992; Piacentini, Cohen, & Cohen, 1992).

Specificity of trait and parent-rated DBD associations were evident, in line with theory of trait mechanisms of DBD (Martel, 2009; Nigg, 2006). Negative affect was associated with most DBD symptom domains, as with most forms of psychopathology (Eisenberg et al., 2009; Lahey, 2009). However, surgency and reactive control were more specifically associated with preschool hyperactivity-impulsivity, and effortful control was most specifically associated with ADHD suggesting children may follow different routes to DBD (Martel, Nigg, & von Eye, 2009; Sonuga-Barke, 2003). Further, interactive and curvilinear effects were notable; effortful control and negative affect interacted to predict parent-rated ADHD, but not ODD, symptoms (Eisenberg et al., 2000; Martel & Nigg, 2006), and reactive control exhibited curvilinear associations with parent-rated ODD and ADHD symptoms (Eisenberg et al., 2003). Within-child constellations of temperament traits, especially extreme temperament traits, may increase risk for developmental psychopathology directly via influence on behavioral propensities, as well as indirectly via interactive effects on socialization influences such as parenting (Belsky, Hsieh, & Crnic, 1998; Lengua et al., 2000). An important direction for future work is to examine whether early temperament traits can prospectively predict the emergence of DBD.

Unfortunately, teacher ratings were only available on approximately half of the sample due to a relatively poor response rate so analyses involving teacher ratings were relatively underpowered. Further, observational measurement of traits were only available from a single paradigm for each trait; multiple measurements of each construct using multiple paradigms might have been useful in order to obtain more reliable, robust observational estimates of traits. Since the current study utilized a community-recruited, DBD-enriched clinical sample, present results should be replicated in other types of samples to assess generalizability.

4.1. Conclusions

Preschoolers with DBD are characterized by higher negative affect and surgency and lower effortful and reactive control than preschoolers without DBD, similar to school-age children. Extreme levels of temperament traits may increase risk for DBD as early as preschool.

Preschoolers with DBD have high negative affect/surgency and low effortful control.

Effortful control and negative affect interact to predict ADHD symptoms.

Reactive control exhibits curvilinear associations with ODD and ADHD.

Extreme levels of temperament traits may be good assessment tools in preschoolers.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40(1):57–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Murphy KR. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A clinical workbook. 3rd Ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels M, Boomsma DI, Hudziak J, Rietveld MJH, van Beijsterveldt TCEM, van den Oord EJCG. Disentangling genetic, environmental, and rater effects on internalizing and externalizing problem behavior in 10-year-old twins. Twin Research. 2004;7(2):162–175. doi: 10.1375/136905204323016140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Hsieh K, Crnic K. Mothering, fathering, and infant negativity as antecedents of boys’ externalizing problems and inhibition at age 3 years: Differential susceptibility to rearing experience? Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:301–319. doi: 10.1017/s095457949800162x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Gould MS, Staghezza B. Aggregating data from multiple informants in child psychiatry epidemiological research. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31(1):78–85. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block B. The Q-sort character appraisal: Encoding subjective impression of persons quantitatively. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association; 2008. California Q-Sort psychometrics; pp. 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Block JH, Block J. The role of ego-control and ego-resiliency in the organization of behavior. In: Collins WA, editor. Development of cognition, affect, and social relations: The Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology. Vol. 13. Hillsdale, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1980. pp. 39–101. [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell DP. Clinical phenomenology and nosology. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1992;1(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- De Pauw SSW, Mervielde I. The role of temperament and personality in problem behaviors of children with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:277–291. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9459-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC, Maszk P, Holmgren R, Suh K. The relations of regulation and emotionality to problem behavior in elementary school children. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:141–162. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Guthrie IK, Fabes RA, Shepard S, Losoya S, Murphy BC, Jones S, Poulin R, Reiser M. Prediction of elementary school children’s externalizing problem behaviors from attentional and behavioral regulation and negative emotionality. Child Development. 2000;71(5):1367–1382. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Fabes RA, Smith CL, Reiser M, Shepard SA, Losoya SH, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC, Cumberland AJ. The relations of effortful control and ego control to children’s resiliency and social functioning. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39(4):761–776. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.4.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Spinrad TL, Cumberland A, Liew J, Reiser M, Zhou Q, Losoya SH. Longitudinal relations of children’s effortful control, impulsivity, and negative emotionality to their externalizing, internalizing, and co-occurring behavior problems. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(4):988–1008. doi: 10.1037/a0016213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Reilly J, Lemery KS, Longley S, Prescott A. The Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery: Preschool version. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Haslam N, Williams B, Prior M, Haslam R, Graetz B, Sawyer M. The latent structure of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A taxonomic analysis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;40(8):639–647. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: Examples from the child-clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65(4):599–610. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huey SJ, Weisz JR. Ego control, ego resiliency, and the Five-Factor model as predictors of behavioral and emotional problems in clinic-referred children and adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:404–415. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Wakschlag LS. Can a valid diagnosis of disruptive behavior disorder be made in preschool children? The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(3):351–358. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Murray KT, Harlan ET. Effortful control in early childhood: Continuity and change, antecedents, and implications for social development. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36(2):220–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB. Public health significance of neuroticism. American Psychologist. 2009;64(4):241–256. doi: 10.1037/a0015309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc N, Boivin M, Dionne G, Brendgen M, Vitaro F, Tremblay RE, et al. The development of hyperactive-impulsive behaviors during the preschool years: The predictive validity of parental assessments. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:977–987. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9227-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, West SG. The additive and interactive effects of parenting and temperament in predicting adjustment problems of children of divorce. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29(2):232–244. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2902_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy F, Hay DA, McStephen M, Wood CH, Waldman I. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A category or a continuum? Genetic analysis of a large-scale twin study. American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:737–744. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majdandzic M, van den Boom DC. Multimethod longitudinal assessment of temperament in early childhood. Journal of Personality. 2007;75(1):121–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel MM. A new perspective on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Emotion dysregulation and trait models. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2009;50(9):1042M–1051. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel MM, Nigg JT. Child ADHD and personality/temperament traits of reactive and effortful control, resiliency, and emotionality. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47(11):1175–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel MM, Nigg JT, von Eye A. How do trait dimensions map onto ADHD symptom domains? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:337–348. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9255-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel MM, Nigg JT, Wong MM, Fitzgerald HE, Jester JM, Puttler LI, Glass JM, Adams KM, Zucker RA. Child and adolescent resiliency, regulation, and executive functioning in relation to adolescent problems and competence in a high-risk sample. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19(2):541–563. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartney K, Burchinal MR, Bub KL. Overton WF, Berry M. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. Vol. 285. 2006. Best practices in quantitative methods for developmentalists; p. 71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mischel W, Shoda Y. A cognitive-affect system theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychological Review. 1995;102(2):246–268. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.102.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Ollendick TH. The role of temperament in the etiology of child psychopathology. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Reviews. 2005;8(4):271–289. doi: 10.1007/s10567-005-8809-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Múthen LK, Múthen BO. MPlus User’s Guide, Fourth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Múthen & Múthen; 1998-2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT. Temperament and developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2006;47(3/4):395–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Goldsmith HH, Sachek J. Temperament and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: The development of a multiple pathway model. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(1):42–53. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson SL, Bates JE, Sandy JM, Schilling EM. Early developmental precursors of impulsive and inattentive behavior: From infancy to middle childhood. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2002;43(4):435–447. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JDA, Majeski SA, Collin VT. ADHD symptoms and personality: Relationships with the five-factor model. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;36:977–987. [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Foster M, Robb JA. The economic impact of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in children and adolescents. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2007;7(1S):121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier J, Collett B, Gimple G, Cowley S. Assessment of disruptive behaviors in preschoolers: Psychometric properties of the Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale and School Situations Questionnaire. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 2006;24(1):3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini JC, Cohen P, Cohen J. Combining discrepant diagnostic information from multiple sources: Are complex algorithms better than simple ones? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1992;20(1):51–63. doi: 10.1007/BF00927116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, Rothbart MK. Development of short and very short forms of the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2006;87(1):103–113. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8701_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins E, Guze SB. Establishment of diagnostic validity in psychiatric illness: Its application to schizophrenia. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1970;126(7):983–986. doi: 10.1176/ajp.126.7.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK. Temperament in childhood: A framework. In: Kohnstamm GA, Bates JE, Rothbart MK, editors. Temperament in Childhood. Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1989. pp. 59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Evans DE. Temperament and personality: Origin and outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;73(1):122–135. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hershey KL, Fisher P. Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. Child Development. 2001;72(5):1394–1408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Posner MI. Temperament, attention, and developmental psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen D, editors. Developmental Psychopathology (Vol. 2): Developmental Neuroscience. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons; 2006. pp. 465–501. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Keenan K, Vondra JI. Developmental precursors of externalizing behavior: Ages 1 to 3. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30(3):355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Shiner R, Caspi A. Personality differences in childhood and adolescence: Measurement, development, and consequences. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2003;44:2–32. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonuga-Barke EJS. The dual pathway model of AD/HD: An elaboration of neuro-developmental characteristics. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2003;27:593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonuga-Barke E, Bitsakou P, Thompson M. Beyond the dual pathway model: Evidence for the dissociation of timing, inhibitory control, and delay-related impairments in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49 (4):345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tackett JL. Evaluating models of the personality-psychopathology relationship in children and adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26:584–599. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Task Force on Research Diagnostic Criteria: Infancy and Preschool. Research diagnostic criteria for infants and preschool children: The process and empirical support. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(12):1504–1512. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000091504.46853.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiente C, Eisenberg N, Smith CL, Reiser M, Fabes RA, Losoya S, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC. The relations of effortful control and reactive control to children’s externalizing problems: A longitudinal assessment. Journal of Personality. 2003;71(6):1171–1196. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag LS, Tolan PH, Leventhal BL. ‘Ain’t misbehavin’: Towards a developmentally-specified nosology for preschool disruptive behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51(1):3–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02184.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]