Abstract

Controlled isomerization of the double bond of certain Diels-Alder reactions provides substrates that, upon oxidation, give rise to products whose gross structure corresponds to that of a Robinson annulation. In these cases, the stereochemistry of the Robinson annulation product reflects the fact that the initial combination occurred in a Diels-Alder mode. Using these principles, we have synthesized carissone and cosmosoic acid. In the latter case, our total synthesis raised serious questions as to the accuracy of the assigned structure of the natural product.

Introduction

Synthetic planning directed to conjugated octalones, of the type 1, traditionally tends to center around enolate and enol based progressions inherent in the expression “Robinson Annulation” (RA, see eq. 1).1,2,3 By contrast, nonconjugated octalone systems of the type 2 are perceived as likely to arise from a Diels-Alder based cycloaddition logic (DA, eq. 2).4,5,6,7

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

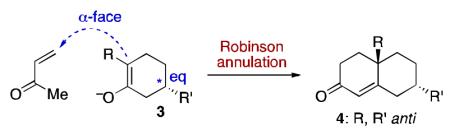

Not surprisingly, these widely used synthetic platforms lead to differing biases in diastereoselection. For instance, consider the consequences of these modalities for orchestrating a 1,4 stereorelationship in a bicyclic product arising from two kinds of cyclohexene substrates – an enolate (3) and an enone (5). In the R A m o d e , diastereofacial induction tends to be stereoelectronically, rather than sterically, driven for the RA progression.8 Thus, if enolate alkylation occurs in the preferred axial sense, with the resident C5 group (asterisk) equatorial, formation of an “anti product,” of the type 4 would be favored.9,10 By contrast, in the DA modality, preferred combination of the DA diene with 5 would tend to occur anti to the R group, leading to a “syn” type product (6).11

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

These differing stereopatterns are also associated with strikingly different displays of the key functional groups (olefin and ketone) in the bicyclic products (compare octalones 1 and 2). Given this situation, we addressed the question as to whether the conventional structural and diastereoselection tendencies can be exploited such that a DA “stereopattern” might be transmitted to a typical RA type product.

Recently, we described a somewhat fortuitous discovery, wherein the double bond of a Diels-Alder derived octalone of the type 7 can be isomerized under mediation by silica gel to afford 8 (Scheme 1).12,13 The latter type of structure is easily seen to be a double bond isomer of a standard Diels-Alder cycloaddition product. It could well be anticipated that Saegusa-Ito-type oxidation14,15 of 8 would give rise to 9, in which a DA stereochemical pattern is ensconced in an RA functional group arrangement (i.e. the expected “wild-type” RA stereomotif would be that shown in 10).

Scheme 1.

Diels-Alder/isomerization sequence.

Attention has already been drawn16 to the potential value of pattern recognition analysis (PRA) as a resource in the planning of the synthesis of complex targets. While the compelling logic of prioritized strategic bond disconnection, advanced by Corey and associates many years ago,17,18 still lies at the heart of contemporary retrosynthetic analysis, PRA, which seeks out identifiable holistic substructural domains, may provide a complementary venue for forward planning.16 Thus, the question we posed above, concerning the permutability of the diastereoselectivity biases of these key reaction types, has the potential to offer new avenues for synthetic planning, particularly in subtle issues of stereochemistry (vide infra, syntheses of carissone19 and of the reported structure of cosmosoic acid20).

Results and Discussion

As shown in Scheme 2, we began our inquiry by demonstrating how two mainstay products of classical RA-based strategies, the Hajos–Parrish ketone (13)21 and the Wieland–Miescher ketone (14),22 could be synthesized in quite reasonable overall yields from the easily available, appropriate α-methylcyclenones.23,24 Of course, in the particular cases of 13 and 14, there were no issues of relative stereochemistry to be addressed. Though we have not yet pursued the matter, enantioselectivity could, in principle, be realized from a catalyst that can impose absolute stereochemical guidance at the stage of the [4+2] cycloaddition event.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Hajos–Parrish ketone (13) and Wieland-Miescher ketone (14).a

aKey: (a) EtAlCl2, CH2Cl2, 0 °C → RT; (b) silica gel, 110 °C, toluene; (c) Pd(OAc)2. *Isomerization ratio.

We next turned to cases bearing C4 substitution on the dienophilic cyclenone substrate. As shown in Scheme 3, the facial stereoselection of the cycloaddition reaction is high (>10:1).25 At this writing, the ratio of Δ2:Δ 3 regioisomers in the double bond migration step in this series was somewhat disappointing.26,27 While the precise factors governing the selectivity of isomerization remain to be determined, they may well reflect minimization of peri interactions between C4 and C6 in the isomerized structure. Fortunately, we were able to retrieve the un-rearranged material and re-subject it to isomerization, thus improving our material throughput. Saegusa-Ito oxidation14,15 proceeded well to afford 17a and 18, respectively. That epimerization had not occurred at C6 during this step, was shown in the case of 17a by its non-identity with compound 17b, previously described and assigned in a rigorous way by Grieco and co-workers.28,29 Subjection of compound 17a to equilibrating conditions did, indeed, lead to epimerization, with emergence of 17b. Thus, the chemistry described above does lead to the otherwise difficultly accessible 6-axially alkylated Δ4 3-octalones.

Scheme 3.

C4–Substituted dienophiles.a

aKey: (a) EtAlCl2, CH2Cl2, 0 °C → RT; (b) silica gel, 110 °C, toluene; (c) 17a: Pd(OAc)2; (d) 18: DDQ, DTBMP. *Isomerization ratio.

This chemistry was next extended to a situation where the substituent on the cyclohexenone dienophile appears at C5. Four cases were examined (Table 1). As seen, the cycloadditions were, again, highly stereoselective, providing substantially one isomer in the Diels-Alder reaction.25 Again, silica gel mediation of the double bond isomerization occurred quite smoothly, this time in higher ratios than those contained in the 4-substituted series. Once again, Saegusa-Ito oxidations14,15 delivered the target octalones, this time bearing a substituent at C7,26 cis to the junction methyl group. This type of series is not readily generated from classical Robinson annulation strategies.

Table 1.

C5–Substituted dienophiles.

| entry | dienophile | isomerized adduct | enone |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

|

|

| 2 |

|

|

|

| 3 |

|

|

|

| 4 |

|

|

|

Key: (a) EtAlCl2, CH2Cl2, 0 °C → RT; (b) silica gel, 110 °C, toluene; (c) Pd(OAc)2; (d) DDQ, DTBMP.

Isomerization ratio.

Adding to the patterns accessible by this logic was the fact that the chemistry is also extendable to the situation where the Diels-Alder diene contains a methyl substituent group at a terminal carbon30 (Table 2). Once again, the levels of face selectivity in the cycloadditions were excellent, giving rise to the major adducts shown. Silica gel mediated isomerizations afforded the “iso-DA-type” products in high ratios relative to starting DA adducts. Following Saegusa oxidation, there were obtained the octalones 33, 35, and 37 with a cis relationship between the junction (C10) and the C6 or C7 substituents.26 As discussed above, this stereopattern is not readily obtained from Robinson annulation strategies, either due to epimerization, in the case of the 6-substituted product, or because of the stereoelectronics of alkylation which govern the case where the substituent is at C7.

Table 2.

Substituted diene.

| entry | dienophile | isomerized adduct | enone |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

|

|

| 2 |

|

|

|

| 3 |

|

|

|

Key: (a) EtAlCl2, CH2Cl2, 0 °C → RT; (b) silica gel, 110 °C, toluene; (c) Pd(OAc)2.

Isomerization ratio.

The applicability of this permuting of RA:DA logic was demonstrated in the context of two total synthesis programs. As will be seen, the targets were selected to exemplify the enhanced possibilities enabled by the chemistry described above. It was for the purpose of synthesizing the sesquiterpene carissone that we conducted the Diels-Alder reaction of 38 with 19.19,31 As shown in Table 2, cycloadition of 38 and 19 gave rise to a cycloadduct which underwent silica induced double bond isomerization, followed by Saegusa oxidation14 to afford 35. Not surprisingly,32 selective reduction of the non-conjugated ketone (C9) could readily be achieved to afford an alcohol (39), which, upon Barton deoxygenation,33 gave rise to 40. Deprotection, as shown, afforded (+)-carissone (41). We note that an elegant total synthesis of (+)-carissone, that does not draw from the chiral pool, has recently been described by Stoltz and colleagues.34 In the Stoltz synthesis, the C7–C10 stereorelationship was also managed through a non-RA program.

Recently, we noted a disclosure in the literature describing the isolation of a compound called cosmosoic acid (42)20 from Cosmos sulphureus, a plant native to Brazil and Mexico. This plant had been identified as a source of anti-malarial natural products, although antimalarial properties of 42, per se, were not reported. The gross structure and stereochemistry of cosmosoic acid had been determined strictly by spectroscopic methods, not supported by any degradative or crystallographic investigations.20 Given the Pattern Recognition Analysis line of thinking,16 one immediately notes the “iso-Diels-Alder” characteristic of cosmosoic acid.35 In this context, C3 of the C3–C4 iso-DA pattern carries a carboxyl group. One might well have considered synthesizing cosmosoic acid by a Diels-Alder reaction of diene 4336 with the generic dienophile 44, followed by isomerization of 45. To us, it seemed that such a program presented unlikely prospects for success. First, dienes of the type 43 tend to be quite unstable.37 Furthermore, the electron withdrawing carboxyl group at C2 would render this diene even less reactive in a hypothesized DA cycloaddition4-6 with an electron withdrawing dienophile of the type 44. Moreover, the key silica gel–mediated isomerization reaction has not been demonstrated in the context of octalin-related DA adducts arising from cycloadducts of the type 45. Instead, we preferred to resort to our usual 2-siloxybutadiene DA building block. If cycloaddition and isomerization would occur with appropriate selectivities, success would depend on converting the subsequently tautomerized ene-siloxy function in 47 to the corresponding unsaturated acid.

In the event, reaction of siloxydiene 4638 with the enone 4439 occurred quite smoothly in the presence EtAlCl2 to provide 49 in 90% yield. Happily, the silica gel–mediated isomerization of 49 proceeded, providing the isomerized silylenol ether (see 47). It seemed prudent to protect the ketone in the light of subsequent operations which were planned (vide infra). Remarkably, it was possible to convert the ketone function of 47 to its corresponding enol ether derivative, 50, via deprotonation with LDA and O-methylation with dimethyl sulfate. This method is not a common one for generating methyl enol ethers from ketones and could warrant future research as to its scope.

With compound 50 in hand, we turned to the conversion of the silylenol ether to the corresponding vinyl triflate. In the event, this subgoal was accomplished by generating the corresponding site-specific enolate via the action of 50 with methyllithium,40 whereupon quenching with the Comins reagent41 afforded the corresponding vinyl triflate 51. With compound 51 in hand, we examined the possibility of a modified Heck-carbonylation.42 Happily, this subgoal was accomplished relatively smoothly (75% yield) under the conditions shown. The intermediate acid was converted to its methyl ester 52. Hydrolysis of the enol ether function gave rise to ketone 53 in an overall yield of 75%. Saponification of the methyl ester gave rise to a product, tentatively assigned as structure 42.

Surprisingly, the NMR spectrum of presumed 42, thus obtained, exhibited certain clear differences from the NMR spectrum reported for cosmosoic acid.43 Obviously, we had reason to be concerned about a possible structural mis-assignment on our part, somewhere during our synthetic work. Upon reexamination of the intermediates generated in the total synthesis progression and our assignments along the way, we remained convinced that we had in fact synthesized 42 as shown. Happily, the matter was objectively established by an X-ray crystal structure of the synthetic material, which clearly revealed the end product of our total synthesis to be compound 42.44 At this stage, it seemed very likely that the structure of the natural product cosmosoic acid does not correspond to that shown in 42. Several attempts were made to network with the original authors,20 but these efforts did not provide any additional insight. No helpful samples or spectral readouts were obtained.

At the time of writing, we can only conclude that the structure of cosmosoic acid does not correspond to 42. Having no access to the natural product, itself, we are unable to provide an informed opinion as to the correct structure of naturally occurring cosmosoic acid.

Finally, we examined substitutions at C6 of the cyclohexenone (which would correspond to C8 of the resulting octalone26). In this connection we studied the case of compound 54.45 Attempted cycloadditions of 54 with diene 46 resulted in approximately 1:1 mixtures.46 Thus, the stereoguidance that we had successfully encountered in the cases of the 4- and 5-substituted 2-methylcyclohexenones, apparently does not provide useful margins with the 6-substituted system (cf. 54).25 This, in itself, is perhaps not surprising in the light of the nature of the Diels-Alder reaction.4-6 In the cycloaddition of a compound such as 54, one envisions the initial orienting bonding would occur at C3 of the cyclohexenone, and slightly later at C2 in the imperfectly concerted cycloaddition. That being the case, the methyl group at C6 would be only weakly directing, since it is in a 1,4-relationship to the emerging “lead” bond.

Conclusion

In summary, we have demonstrated modalities for permuting the stereochemistry and gross structural patterns emerging from a classical Robinson annulation (RA), with Diels-Alder (DA)-based technologies. The line of reasoning has led to stereospecific syntheses of carissone and the previously assigned structure of cosmosoic acid. In the latter case, the total synthesis work suggests that the structural assignment of the natural product is in error. We are hopeful that the successful demonstrations provided above for broadening the accessible relationships applicable to PRA can be applied to interchanging the structural and stereomotifs of other reaction dualities.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 4.

Total synthesis of (+)-carissone.

aKey: (a) EtAlCl2, CH2Cl2, 0 °C → RT; (b) silica gel, 110 °C, toluene, 94% yield, 15:1 isomerization ratio; (c) Pd(OAc)2, 79% yield; (d) NaBH4, EtOH, 0 °C, 95% yield; (e) TCDI, DMAP, toluene; then AIBN, Bu3SnH, 65% yield; (f) BrBMe2, DCM, –78 °C, 90%.

Scheme 5.

Synthetic strategy toward cosmosoic acid.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of 42.

aKey: (a) EtAlCl2, CH2Cl2, 0 °C → RT, 90% yield, (b) silica gel, 110 °C, toluene, 85% yield, 5:1 isomerization ratio, (c) LDA, Me2SO4, THF, –78 °C, 80% yield, (d) MeLi, PhNTf2, THF, 88% yield, (e) Pd(OAc)2, PPh3, Et3N, CO balloon, MeOH/DMF, (f) 1 N HCl, two steps 75% yield, (g) LiOH, THF/H2O, 95% yield.

Scheme 7.

DA of 6-Substituted Diene Systems.

aKey: (a) EtAlCl2, CH2Cl2, 0 °C → RT, 82%.

Acknowledgements

Financial support was provide by the National Institutes of Health (HL25848).

Notes and References

- 1.Rapson WS, Robinson R. J. Chem. Soc. 1935:1285–1288. [Google Scholar]

- 2 (a).Gawley RE. Synthesis. 1976:777–794. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jung ME. Tetrahedron. 1976;32:3–31. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heathcock CH. In: Comp. Org. Synth. Trost BM, Fleming I, editors. Vol. 1. Pergamon Press; Oxford: 1991. pp. 133–179. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diels O, Alder K. Ann. 1928;460:98–122. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oppolzer W. Intermolecular Diels-Alder Reactions. In: Trost BM, Fleming I, editors. Comp. Org. Synth. Vol. 5. Pergamon Press; Oxford: 1991. pp. 315–401. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicolaou KC, Snyder SA, Montagnon T, Vassilikogiannakis G. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:1668–1698. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020517)41:10<1668::aid-anie1668>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7 (a).Corey EJ, Guzman-Perez A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:388–401. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980302)37:4<388::AID-ANIE388>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Corey EJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:1650–1667. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020517)41:10<1650::aid-anie1650>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Corey EJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:2100–2117. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.House HO, Umen MJ. J. Org. Chem. 1973;38:1000–1003. [Google Scholar]

- 9 (a).Howe R, McQuillin FJ. J. Chem. Soc. 1955:2423–2428. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wenkert E, Berges DA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967;89:2507–2509. doi: 10.1021/ja00986a061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Heathcock CH, Graham SL, Pirrung MC, Flavac F, White CT. In: The Total Synthesis of Natural Products. ApSimon JE, editor. Vol. 5. Wiley; New York: 1983. p. 129. [Google Scholar]

- 10 (a).Caine D, Gupton JT. J. Org. Chem. 1974;39:2654–2656. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fringuelli F, Taticchi A, De Giuli G. Gazz. Chim. Ital. 1969;99:219–130. [Google Scholar]

- 11 (a).Harayama T, Cho H, Inubushi Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975;31:2693–2696. [Google Scholar]; (b) Oppolzer W, Petrzilka M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976;98:6722–6723. [Google Scholar]; (c) Angell EC, Fringuelli F, Minuti L, Pizzo F, Porter B, Taticchi A, Wenkert E. J. Org. Chem. 1985;50:686–4690. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haaksma AA, Jansen BJM, de Groot A. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:3121–3130. [Google Scholar]

- 13 (a).Angeles AR, Dorn DC, Kou CA, Moore MAS, Danishefsky SJ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:1451–1454. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Angeles AR, Waters SP, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13765–13770. doi: 10.1021/ja8048207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito Y, Hirao T, Saegusa T. J. Org. Chem. 1978;43:1011–1013. [Google Scholar]

- 15 (a).For other methods to accomplish this goal, see: Jung ME, Pan Y, Rathke MW, Sullivan DF, Woodbury RP. J. Org. Chem. 1977;42:3961–3963. Zhang H, Reddy MS, Phoenix SP, Deslongchamps P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:1272–1275. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704959.

- 16.Wilson RM, Danishefsky SJ. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:4293–4305. doi: 10.1021/jo070871s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17 (a).Corey EJ. Pure Appl. Chem. 1967:19–37. [Google Scholar]; (b) Corey EJ, Wipke WT. Science. 1969;166:178–192. doi: 10.1126/science.166.3902.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Corey EJ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1991;30:455–612. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corey EJ, Cheng X. The Logic of Chemical Synthesis. Wiley-VCH; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19 (a).Carissone isolation and bioactivity: Mohr K, Schindler O, Reichstein T. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1954;37:462–471. Joshi DV, Boyce SF. J. Org. Chem. 1957;22:95–97. Lindsay EA, Berry Y, Jamie JF, Bremner JB. Phytochemistry. 2000;55:403–406. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00343-5.

- 20.Wu J, Chang Y-F, Tung Y-T, Tsuzuki M, Izuka A, Wang S-Y, Kuo Y-H. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2010;93:753–756. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hajos ZG. J. Org. Chem. 1974;39:1615–1621. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wieland P, Miescher K. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1950;33:2215. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19480310650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Funk R, Vollhardt KPC. Synthesis. 1980;2:118–119. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warnhoff EW, Martin EG, Johnson WS. Organic Syntheses. 1957;37:8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angell EC, Fringuelli F, Pizzo F, Porter B, Taticchi A, Wenkert E. J. Org. Chem. 1986;51:2642–2649. [Google Scholar]

- 26.In this write-up, we employ the well-known numbering system used to identify carbon atoms in the AB rings of steroids.

- 27.In several instances, it was shown that the ratios of the Δ2:Δ 3 silyl enol ether isomers were virtually the same when we started with either of the components. Thus, it seems likely that we are generating substantially an equilibrium mixture. We also note that favoring of Δ2:Δ 3 isomer in these cis-fused compounds correlates well with the enolization tendencies of cis-fused decalones.

- 28 (a).(b) Grieco PA, Oguri T, Wang CJ, Williams E. J. Org. Chem. 1977;42:4113–4118. [Google Scholar]; (c) Grieco PA, Oguri T, Gilman S, DeTitta GT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978;100:1616–1617. [Google Scholar]; (d) Kato M, Kurihara H, Kosugi H, Watanae M, Asuka S, Yoshikoshi A. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin 1. 1977:2433–2436. A. [Google Scholar]; The detailed mechanism of this isomerization is unclear. It must involve electrophilic attack (either by proton or by a silicon-derived species) at C2 and deprotonation at C4. For a possible precedent for this type of silyl enol ether chemistry, see: Telschowand J, Reusch W. J. Org. Chem. 1975;40:862–865.

- 29 (a).Collins DJ, Hobbs JJ, Steinhell S. Aust. J. Chem. 1963;16:1030–1033. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wittstruck TA, Malhotra SK, Ringold HJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963;85:1699–1670. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu P, Sirois LE, Cheong PH, Yu Z, Hartung IV, Rieck H, Wender PA, Houk KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10127–10135. doi: 10.1021/ja103253d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mori K, Igarashi Y. Liebigs Annalen der Chemie. 1988;1:93–95. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hiroi K, Yamada S. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1975;23:1103–1107. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barton DHR, McCombie SW. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1975:1574–1585. [Google Scholar]

- 34 (a).For a synthesis of carissone, see: Levine SR, Krout MR, Stoltz BM. Org. Lett. 2009;11:289–292. doi: 10.1021/ol802409h. and refs cited there. For a route to carissone using general Robinson annulation logic followed by bond fragmentation, see: Aoyama Y, Araki Y, Konoike T. Synlett. 2001:1452–1454.

- 35 (a).Carter MJ, Fleming I. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1985:533–534. Carter MJ, Fleming I, Percival A. J. Chem. Soc. Perking Trans. 1. 1981:2415–2434. Sammis GM, Flamme EM, Xie H, Ho DM, Sorensen EJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:8612–8613. doi: 10.1021/ja052383c. Xie H, Sammis GM, Flamme EM, Kraml CM, Sorensen EJ. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:11131–11134. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102394. DA-Allylation Reactions: Vaultier M, Truchet F, Carboni B, Hoffmann RW, Denne I. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:4169–4172. Tailor J, Hall DG. Org. Lett. 2000;2:3715–3718. doi: 10.1021/ol006626b. Toure BB, Hoveyda HR, Tailor J, lesanko A. Ulaczky, Hall DG. Chem. Eur. J. 2003;9:466–474. doi: 10.1002/chem.200390049. Gao X, Hall DG. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:2231–2235. Gao X, Hall DG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:9308–9309. doi: 10.1021/ja036368o. Li D, Liu G, Hu Q, Wang C, Xi Z. Org. Lett. 2007;9:5433–5436. doi: 10.1021/ol702379s.

- 36.McIntosh JM, Sieler RA. J. Org. Chem. 1978;43:4431–4433. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poly W, Schomburg S, Hoffmann HMR. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:3701–3710. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones DW, Lock CJ. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1995;21:2747–2755. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicolaou KC, Wu TR, Sarlah D, Shaw DM, Rowcliffe E, Burton DR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:11114–11121. doi: 10.1021/ja802805c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stork G, Hudrlik PF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968;90:4464–4465. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Comins DL, Dehgani A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:6299–6302. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Findley TJK, Sucunza D, Miller LC, Davies DT, Procter DJ. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:6862–6865. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.See Supporting Information

- 44.See Supporting Information

- 45.Banwell MG, Jury JC. Organic Preparations and Procedures International. 2004;36:87–91. [Google Scholar]

- 46.At this writing, it is not clear whether the mixture strictly reflects the kinetic ratio of cycloaddition or some subsequent epimerization.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.