Abstract

Objective To do an indirect comparison analysis of apixaban against dabigatran etexilate (2 doses) and rivaroxaban (1 dose), as well as of rivaroxaban against dabigatranetexilate (2 doses), for their relative efficacy and safety against each other, with particular focus on the secondary prevention population for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. A secondary objective was to do the same analysis in the primary prevention cohort.

Design Indirect treatment comparisons of phase III clinical trials of stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation, with a focus on the secondary prevention cohorts. A secondary analysis was done on the primary prevention cohort.

Data sources Medline and Central (up to June 2012), clinical trials registers, conference proceedings, and websites of regulatory agencies.

Study selection Randomised controlled trials of rivaroxaban, dabigatran, or apixaban compared with warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation.

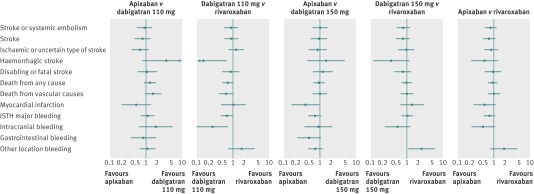

Results In the secondary prevention (previous stroke) subgroup, when apixaban was compared with dabigatran (110 mg and 150 mg twice daily) for efficacy and safety endpoints, the only significant difference seen was less myocardial infarction (hazard ratio 0.39, 95% confidence interval 0.16 to 0.95) with apixaban compared with dabigatran 150 mg twice daily. No significant differences were seen in efficacy and most safety endpoints between apixaban or dabigatran 150 mg twice daily versus rivaroxaban. Less haemorrhagic stroke (hazard ratio 0.15, 0.03 to 0.66), vascular death (0.64, 0.42 to 0.99), major bleeding (0.68, 0.47 to 0.99), and intracranial bleeding (0.27, 0.10 to 0.73) were seen with dabigatran 110 mg twice daily versus rivaroxaban. In the primary prevention (no previous stroke) subgroup, apixaban was superior to dabigatran 110 mg twice daily for disabling or fatal stroke (hazard ratio 0.59, 0.36 to 0.97). Compared with dabigatran 150 mg twice daily, apixaban was associated with more stroke (hazard ratio 1.45, 1.01 to 2.08) and with less major bleeding (0.75, 0.60 to 0.94), gastrointestinal bleeding (0.61, 0.42 to 0.89), and other location bleeding (0.74, 0.58 to 0.94). Compared with rivaroxaban, dabigatran 110 mg twice daily was associated with more myocardial infarction events. No significant differences were seen for the main efficacy and safety endpoints between dabigatran 150 mg twice daily and rivaroxaban, or in efficacy endpoints between apixaban and rivaroxaban. Apixaban was associated with less major bleeding (hazard ratio 0.61, 0.48 to 0.78) than rivaroxaban.

Conclusions For secondary prevention, apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran had broadly similar efficacy for the main endpoints, although the endpoints of haemorrhagic stroke, vascular death, major bleeding, and intracranial bleeding were less common with dabigatran 110 mg twice daily than with rivaroxaban. For primary prevention, the three drugs showed some differences in relation to efficacy and bleeding. These results are hypothesis generating and should be confirmed in a head to head randomised trial.

Introduction

Impressive phase III clinical trials against warfarin have been published for the novel oral anticoagulants—that is, the direct thrombin inhibitors (dabigatran) and the factor Xa inhibitors (for example, rivaroxaban, apixaban). All showed non-inferiority for the primary efficacy endpoint of stroke and systemic embolism; dabigatran 150 mg twice daily and apixaban achieved superiority over warfarin for this endpoint.1 With regards to safety, dabigatran 110 mg twice daily and apixaban had significantly less major bleeding (by 20% and 31%) compared with warfarin.

On the basis of these phase III trials, dabigatran (150 mg and 110 mg twice daily) and rivaroxaban are now approved for prevention of stroke in many countries. In Europe, the European Medicines Agency label recommends 150 mg twice daily for most patients, with the 110 mg twice daily dose recommended in people aged over 80, those taking interacting drugs such as verapamil, and those at high risk of bleeding. In the United States, dabigatran 110 mg twice daily is not available but use of a 75 mg twice daily dose is approved for patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance 15-29 mL/min) despite the absence of randomised trial evidence for this dose in atrial fibrillation. Apixaban is under regulatory submission.

A question remains as to which of the novel agents is best, in terms of efficacy and safety. In the absence of head to head trials, one method of making such a comparison is by an indirect comparison analysis. We recently published an indirect comparison analysis based on the overall clinical trial results, in which we found a significantly lower risk of stroke and systemic embolism (by 26%) for dabigatran (150 mg twice daily) compared with rivaroxaban, as well as of haemorrhagic stroke and non-disabling stroke.2 We found no significant differences for apixaban versus dabigatran (both doses) or rivaroxaban or for rivaroxaban versus dabigatran 110 mg twice daily in preventing stroke and systemic embolism. For ischaemic stroke, we found no significant differences between the novel agents. Major bleeding was significantly lower with apixaban than with dabigatran 150 mg twice daily (by 26%) and rivaroxaban (by 34%), but it was not significantly different from dabigatran 110 mg twice daily. When compared with rivaroxaban, dabigatran 110 mg twice daily was associated with less major bleeding (by 23%) and intracranial bleeding (by 54%). A subsequent indirect comparison analysis by Mantha and Ansell confirmed these results.3

Nevertheless, a comparison using one whole trial population against another is limited by very important heterogeneity between populations. In particular, the ROCKET-AF trial studied a population at much higher risk of stroke (mean CHADS2 score 3.5; 55% secondary prevention)4 compared with the RE-LY and ARISTOTLE trials (mean CHADS2 score 2.1; 20% and19% secondary prevention).5 6 7 One possible strategy to minimise the inter-trial heterogeneity is to use published data from the secondary prevention subgroups of the different trials with dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban to do the indirect comparison, thus allowing some degree of homogeneity of the study populations.

The aim of this study was to do an indirect comparison analysis of apixaban against dabigatran etexilate (two doses) and rivaroxaban, as well as of rivaroxaban against dabigatran etexilate (two doses), for their relative efficacy and safety against each other, with a particular focus on the secondary prevention population (patients with previous stroke). A secondary aim was to do the same analysis in the primary prevention cohort.

Methods

Following a literature search of Medline and Central (up to June 2012), clinical trials registers, conference proceedings, and websites of regulatory agencies, we reviewed the main efficacy and safety endpoints from the published secondary prevention cohorts of the RE-LY, ROCKET-AF, and ARISTOTLE clinical trials for comparability and consistency of definitions (see supplementary table A for the complete summary of trials’ characteristics).8 9 10 On the basis of their respective trial publications,8 9 10 supplementary table B summarises the patients’ characteristics in the secondary prevention cohort. Our efficacy and safety endpoints of interest were similar to those in our previous analysis.2

We compared data from only RE-LY, ROCKET-AF, and ARISTOTLE, as apart from these three randomised trials no other phase III trials have compared the new oral anticoagulants with warfarin or against each other in head to head trials. Thus, we did not do a formal systematic review and meta-analysis. Our primary focus was on the secondary prevention cohort to avoid inter-trial heterogeneity.

We used the so-called Bucher method for indirect comparisons using a common comparator,11 which is a statistical method for estimating the hazard rate ratio and corresponding uncertainty. The method is recommended as a preferred method for indirect comparison,8 superior to informal methods such as comparison of confidence intervals. For these comparisons, we let HRAB and HRCB be the reported hazard rate ratio of treatment A versus B and of treatment C versus B. Observing that B is the common reference comparator (warfarin), HRAC may be estimated as HRAC=HRAB/HRCB. We estimated a confidence interval by using the reported confidence intervals (CIl, CIu). We estimated the standard error (SE) of log(HR) as ½(log(CIu)−log(CIl))/1.96, where 1.96 is the 97.5% fractile of the standard normal distribution. The variance of log(HRAC), (SEAC)2, is under independence given as (SEAB)2+(SECB)2, so a 95% confidence interval of HRAC is exp(log(HRAC)±1.96×SEAC). Reported P values are for the hypothesis H0:log(HRAC)=0 versus HA:log(HRAC)≠0, assuming log(HRAC) is normal with variance (SEAC)2.

The application of the method relies on a similarity assumption that the hazard rate ratio HRAB was likely also to be obtained if it was based on the population from which HRCB was estimated.12 Importantly, the most direct way to consider this similarity assumption valid is to require that the clinical studies are absolutely comparable in terms of populations’ characteristics and conduct of the experiment (and as highlighted earlier, some differences exist between the whole trials, as shown in supplementary table A). However, inter-trial differences in population characteristics are minimised for the secondary prevention cohort (see supplementary table B), allowing the indirect comparisons.

Firstly, we estimated the expected effect of “any novel anticoagulant” versus warfarin as a weighted average by using the inverse of the variance of the log(HR) as weights. We used only results from the dabigatran 150 mg twice daily arm of the RE-LY study in combination with data from ARISTOTLE and ROCKET-AF to ensure independence between the components of the average. We made no statistical adjustments for multiple comparisons within this study. The second focus in this analysis was the indirect comparisons of apixaban versus dabigatran (both doses) and rivaroxaban, as well as rivaroxaban versus dabigatran (both doses). Direct comparisons of “dabigatran 110 mg twice daily versus dabigatran 150 mg twice daily” were already available from the RELY trial.5 6 We used Stata 11.2, R v2.12.1, and Microsoft Excel 2003 for Windows for the statistical analyses and graphical presentation.

Results

Secondary prevention (previous stroke) subgroup

As shown in supplementary table B, the mean age was comparable in the secondary prevention subgroups of all three trials (approximately 71 years), as was the proportion of women (approximately 38%). The risk profile according to CHADS2 score was also broadly similar, as were the proportions with diabetes mellitus (23-26%), hypertension (77-85%), and previous use of a vitamin K antagonist (56-61%).

When we compared apixaban with dabigatran (110 mg and 150 mg twice daily) for efficacy and safety endpoints, the only significant difference seen was less myocardial infarction (hazard ratio 0.39, 95% confidence interval 0.16 to 0.95) for apixaban compared with dabigatran 150 mg twice daily (table 1).

Table 1.

Indirect estimates of hazard ratio (95% CI), Bucher method

| Apixaban v dabigatran 110 mg | Apixaban v dabigatran 150 mg | Apixaban v rivaroxaban | Dabigatran 110 mg v rivaroxaban | Dabigatran 150 mg v rivaroxaban | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary prevention (previous stroke) subgroup | |||||

| Stroke or systemic embolism | 0.90 (0.56 to 1.45) | 1.01 (0.63 to 1.63) | 0.81 (0.56 to 1.17) | 0.89 (0.59 to 1.36) | 0.80 (0.52 to 1.21) |

| Stroke | 0.80 (0.49 to 1.30) | 0.93 (0.57 to 1.53) | 0.72 (0.49 to 1.06) | 0.91 (0.59 to 1.40) | 0.78 (0.50 to 1.20) |

| Ischaemic or uncertain type of stroke | 0.68 (0.40 to 1.17) | 0.86 (0.49 to 1.50) | 0.83 (0.55 to 1.27) | 1.22 (0.77 to 1.95) | 0.97 (0.60 to 1.58) |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 3.64 (0.79 to 16.7) | 1.48 (0.45 to 4.85) | 0.55 (0.23 to 1.29) | 0.15 (0.03 to 0.66) | 0.37 (0.12 to 1.14) |

| Disabling or fatal stroke | 1.07 (0.58 to 1.98) | 1.21 (0.65 to 2.24) | 0.94 (0.56 to 1.56) | 0.87 (0.52 to 1.47) | 0.77 (0.46 to 1.31) |

| Death from any cause | 1.27 (0.88 to 1.84) | 0.94 (0.66 to 1.33) | 0.92 (0.69 to 1.22) | 0.72 (0.52 to 1.00) | 0.98 (0.72 to 1.34) |

| Death from vascular causes | 1.56 (0.95 to 2.56) | 1.00 (0.63 to 1.59) | 1.00 (0.69 to 1.46) | 0.64 (0.42 to 0.99) | 1.00 (0.68 to 1.47) |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.53 (0.21 to 1.32) | 0.39 (0.16 to 0.95) | 0.55 (0.27 to 1.11) | 1.04 (0.48 to 2.24) | 1.39 (0.67 to 2.89) |

| ISTH major bleeding | 1.11 (0.72 to 1.69) | 0.72 (0.48 to 1.08) | 0.75 (0.53 to 1.07) | 0.68 (0.47 to 0.99) | 1.04 (0.74 to 1.47) |

| Intracranial bleeding | 1.85 (0.64 to 5.33) | 0.90 (0.37 to 2.18) | 0.50 (0.24 to 1.04) | 0.27 (0.10 to 0.73) | 0.55 (0.25 to 1.23) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 0.84 (0.38 to 1.85) | 0.50 (0.23 to 1.06) | – | – | – |

| Other location bleeding | 1.10 (0.68 to 1.80) | 0.75 (0.47 to 1.20) | 1.92 (0.83 to 4.46) | 1.74 (0.75 to 4.04) | 2.56 (1.12 to 5.88) |

| Primary prevention (no previous stroke) subgroup | |||||

| Stroke or systemic embolism | 0.88 (0.63 to 1.23) | 1.37 (0.95 to 1.96) | 1.06 (0.74 to 1.53) | 1.21 (0.84 to 1.74) | 0.78 (0.53 to 1.15) |

| Stroke | 0.91 (0.65 to 1.28) | 1.45 (1.01 to 2.08) | 1.11 (0.77 to 1.59) | 1.21 (0.83 to 1.77) | 0.76 (0.51 to 1.14) |

| Ischaemic or uncertain type of stroke | 0.93 (0.64 to 1.36) | 1.47 (0.98 to 2.21) | 1.10 (0.73 to 1.67) | 1.18 (0.78 to 1.79) | 0.75 (0.48 to 1.17) |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 1.34 (0.59 to 3.06) | 2.36 (0.90 to 6.17) | 1.44 (0.61 to 3.37) | 1.07 (0.40 to 2.87) | 0.61 (0.20 to 1.83) |

| Disabling or fatal stroke | 0.59 (0.36 to 0.97) | 0.97 (0.58 to 1.63) | 1.03 (0.60 to 1.79) | 1.74 (1.04 to 2.93) | 1.07 (0.62 to 1.84) |

| Death from any cause | 0.94 (0.77 to 1.14) | 1.05 (0.86 to 1.27) | 1.02 (0.83 to 1.25) | 1.09 (0.88 to 1.35) | 0.98 (0.79 to 1.21) |

| Death from vascular causes | 0.89 (0.69 to 1.14) | 1.09 (0.84 to 1.40) | 0.98 (0.75 to 1.27) | 1.10 (0.84 to 1.44) | 0.90 (0.68 to 1.18) |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.73 (0.46 to 1.16) | 0.82 (0.51 to 1.31) | 1.26 (0.80 to 1.99) | 1.73 (1.09 to 2.75) | 1.55 (0.96 to 2.48) |

| ISTH major bleeding | 0.80 (0.64 to 1.00) | 0.75 (0.60 to 0.94) | 0.61 (0.48 to 0.78) | 0.77 (0.60 to 0.98) | 0.82 (0.64 to 1.05) |

| Intracranial bleeding | 1.26 (0.67 to 2.37) | 1.02 (0.56 to 1.88) | 0.77 (0.40 to 1.49) | 0.61 (0.30 to 1.27) | 0.75 (0.38 to 1.52) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 0.78 (0.53 to 1.16) | 0.61 (0.42 to 0.89) | – | – | – |

| Other location bleeding | 0.78 (0.61 to 1.00) | 0.74 (0.58 to 0.94) | 1.23 (0.55 to 2.72) | 1.57 (0.71 to 3.48) | 1.67 (0.76 to 3.70) |

ISTH=International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

We found no significant differences in efficacy and most safety endpoints between apixaban or dabigatran 150 mg and rivaroxaban. The exception was “other location bleeding,” which was higher with dabigatran 150 mg twice daily than with rivaroxaban, although the 95% confidence intervals were wide. Significantly less haemorrhagic stroke (hazard ratio 0.15, 0.03 to 0.66), vascular death (0.64, 0.42 to 0.99), major bleeding (0.68, 0.47 to 0.99), and intracranial bleeding (0.27, 0.10 to 0.73) occurred with dabigatran 110 mg twice daily than with rivaroxaban. The figure shows forest plots for the comparisons.

Forest plots of hazard ratio (95% CI) for indirect comparisons between apixaban, dabigatran (110 mg and 150 mg twice daily), and rivaroxaban for secondary prevention of stroke in atrial fibrillation. ISTH=International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis

Primary prevention (no previous stroke) subgroup

In the primary prevention cohort, apixaban was superior to dabigatran 110 mg twice daily for disabling or fatal stroke (hazard ratio 0.59, 0.36 to 0.97). Compared with dabigatran 150 mg twice daily, apixaban was associated with more stroke (hazard ratio 1.45, 1.01 to 2.08) and with less major bleeding (0.75, 0.60 to 0.94), gastrointestinal bleeding (0.61, 0.42 to 0.89), and other location bleeding (0.74, 0.58 to 0.94) (table 1).

Dabigatran 110 mg twice daily was associated with more disabling or fatal stroke (hazard ratio 1.74, 1.04 to 2.93) and myocardial infarction (1.73, 1.09 to 2.75) compared with rivaroxaban, but the 95% confidence intervals are wide. We found no significant differences for efficacy and safety endpoints between dabigatran 150 mg twice daily and rivaroxaban or in efficacy endpoints between apixaban and rivaroxaban. Apixaban was associated with less major bleeding (hazard ratio 0.61, 0.48 to 0.78) than rivaroxaban.

Overall effect of novel oral anticoagulants versus warfarin

In the secondary prevention cohort (table 2), for any novel oral anticoagulant (dabigatran 110 mg twice daily, apixaban, rivaroxaban) versus warfarin, we found significant reductions in haemorrhagic stroke (P=0.001), major bleeding (P=0.012), and intracranial bleeding (P<0.001).

Table 2.

Overall effect of novel oral anticoagulants versus warfarin in secondary prevention (previous stroke) subgroup

| Outcome | Any NOAC (dabigatran 110 mg twice daily, apixaban, rivaroxaban*) v warfarin | Any NOAC (dabigatran 150 mg twice daily, apixaban, rivaroxaban*) v warfarin | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted average effect—hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | Weighted average effect—hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Stroke or systemic embolism | 0.87 (0.75 to 1.02) | 0.083 | 0.86 (0.73 to 1.00) | 0.047 | |

| Stroke | 0.89 (0.76 to 1.04) | 0.142 | 0.86 (0.74 to 1.01) | 0.070 | |

| Ischaemic or uncertain type of stroke | 1.02 (0.86 to 1.23) | 0.798 | 0.98 (0.82 to 1.17) | 0.825 | |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 0.50 (0.33 to 0.74) | 0.001 | 0.51 (0.35 to 0.75) | 0.001 | |

| Disabling or fatal stroke | 0.89 (0.72 to 1.09) | 0.260 | 0.87 (0.70 to 1.07) | 0.174 | |

| Death from anycause | 0.89 (0.79 to 1.01) | 0.070 | 0.94 (0.84 to 1.07) | 0.350 | |

| Death from vascular causes | 0.91 (0.78 to 1.06) | 0.238 | 0.98 (0.84 to 1.14) | 0.793 | |

| Myocardial infarction | 1.00 (0.76 to 1.32) | 0.997 | 1.06 (0.80 to 1.40) | 0.682 | |

| ISTH major bleeding | 0.83 (0.71 to 0.96) | 0.012 | 0.91 (0.79 to 1.06) | 0.221 | |

| Intracranial bleeding | 0.49 (0.36 to 0.69) | <0.001 | 0.53 (0.39 to 0.73) | <0.001 | |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 0.93 (0.63 to 1.36) | 0.698 | 1.34 (0.94 to 1.90) | 0.106 | |

| Other location bleeding | 0.86 (0.69 to 1.09) | 0.219 | 1.05 (0.84 to 1.31) | 0.675 | |

ISTH=International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis; NOAC=novel oral anticoagulant.

*Rivaroxaban not included for gastrointestinal bleeding outcome.

In the primary prevention cohort (table 3)], for any novel oral anticoagulant (dabigatran 110 mg twice daily, apixaban, rivaroxaban) versus warfarin, we found significant reductions in stroke/systemic embolism (P=0.019), stroke (P=0.022), haemorrhagic stroke (P<0.001), disabling/fatal stroke (P=0.005), and death (P=0.03). In terms of safety endpoints, less major bleeding and intracranial bleeding occurred (both P<0.001).

Table 3.

Overall effect of novel oral anticoagulants versus warfarin in primary prevention (no previous stroke) subgroup

| Outcome | Any NOAC (dabigatran 110 mg twice daily, apixaban, rivaroxaban*) v warfarin | Any NOAC (dabigatran 150 mg twice daily, apixaban, rivaroxaban*) v warfarin | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted average effect—hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | Weighted average effect—hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Stroke or systemic embolism | 0.84 (0.73 to 0.97) | 0.019 | 0.74 (0.63 to 0.85) | <0.001 | |

| Stroke | 0.85 (0.73 to 0.98) | 0.022 | 0.73 (0.63 to 0.85) | <0.001 | |

| Ischaemic or uncertain type of stroke | 0.97 (0.82 to 1.14) | 0.714 | 0.84 (0.71 to 1.00) | 0.043 | |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 0.51 (0.36 to 0.71) | <0.001 | 0.46 (0.33 to 0.66) | <0.001 | |

| Disabling or fatal stroke | 0.74 (0.60 to 0.91) | 0.005 | 0.60 (0.48 to 0.75) | <0.001 | |

| Death from any cause | 0.91 (0.84 to 0.99) | 0.030 | 0.88 (0.81 to 0.96) | 0.003 | |

| Death from vascular causes | 0.91 (0.82 to 1.01) | 0.089 | 0.85 (0.77 to 0.95) | 0.003 | |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.99 (0.82 to 1.20) | 0.937 | 0.95 (0.79 to 1.15) | 0.625 | |

| ISTH major bleeding | 0.84 (0.76 to 0.93) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.78 to 0.95) | 0.003 | |

| Intracranial bleeding | 0.44 (0.34 to 0.58) | <0.001 | 0.47 (0.36 to 0.60) | <0.001 | |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 1.00 (0.83 to 1.21) | 0.999 | 1.17 (0.97 to 1.41) | 0.094 | |

| Other location bleeding | 0.85 (0.75 to 0.96) | 0.007 | 0.88 (0.78 to 0.99) | 0.031 | |

ISTH=International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis; NOAC=novel oral anticoagulant.

*Rivaroxaban not included for gastrointestinal bleeding outcome.

When we used dabigatran 150 mg twice daily for this pooled analysis—that is, novel oral anticoagulant (dabigatran 150 mg twice daily, apixaban, rivaroxaban) versus warfarin—we still found significant reductions in stroke/systemic embolism and stroke (both P<0.001), ischaemic stroke (P=0.043), haemorrhagic stroke and disabling/fatal stroke (both P<0.001), death (P=0.003), and vascular mortality (P=0.003). For safety, significantly less major bleeding (P=0.003) and intracranial bleeding (P<0.001) occurred.

Discussion

An indirect comparison analysis has important limitations, but some differential effects for primary and secondary prevention of stroke may be evident with the novel oral anticoagulant drugs in atrial fibrillation. Our approach using published data from the secondary prevention subgroups of the different trials to do the indirect comparison minimises the important inter-trial heterogeneity (especially for the ROCKET-AF trial),8 9 10 thus allowing for some degree of homogeneity of study population for our indirect comparisons of the three novel anticoagulants.

In the analysis focused on indirect comparisons of the “high risk” secondary prevention cohort included in recent randomised trials, we found no profound differences in efficacy and safety endpoints for apixaban compared with dabigatran (both doses) or rivaroxaban, although haemorrhagic stroke, vascular death, major bleeding, and intracranial bleeding were less common with dabigatran 110 mg twice daily than with rivaroxaban.

In the secondary prevention cohort, myocardial infarction was less common only with apixaban compared with dabigatran 150 mg twice daily. For other indirect comparisons, no difference was seen. A non-significant numerical increase in myocardial infarction events was seen in the main RE-LY trial,6 but this did not translate into more hospital admissions for angina or more revascularisations, and dabigatran 150 mg twice daily was associated with significantly less vascular mortality.13 Also, no difference was apparent in cardiac events between patients with or without previous myocardial infarction, and the overall benefit in terms of the reduction in stroke and serious bleeding far outweighed the small absolute difference in myocardial infarction events with dabigatran.13

In the primary prevention cohort, the three drugs showed some differences in relation to efficacy and bleeding. Dabigatran 150 mg twice daily was associated with significantly less stroke but more major bleeding events compared with apixaban. Apixaban was associated with similar efficacy but less major bleeding compared with rivaroxaban. When rivaroxaban was compared with dabigatran 110 mg twice daily, the latter had lower efficacy for the prevention of disabling/fatal stroke and was associated with more myocardial infarction events. We noted no profound differences for safety and efficacy between dabigatran 150 mg twice daily and rivaroxaban.

This analysis extends previous studies of indirect comparisons of the whole trial results,2 3 by focusing separately on the secondary and primary prevention cohorts and thus avoiding a degree of population heterogeneity that was inherent in previous analyses, including one from our group.2 This is pertinent given that the overall main study population of ROCKET-AF was at much higher risk compared with the RE-LY and ARISTOTLE trials.

Our analysis also shows that the novel oral anticoagulants as a whole provide additional benefits over warfarin, in both secondary and primary prevention. However, well controlled, adjusted dose warfarin is associated with less stroke and serious bleeding than is poorly controlled warfarin,14 15 and this indirect comparison cannot adjust for this or investigate this aspect. In the trials, the average time in the therapeutic range was 55% in ROCKET-AF, 64% in RE-LY, and 62% in ARISTOTLE; however, wide variation in mean time in therapeutic range between countries is evident.16 Patients in the highest quarter of average centre based (not individual) time in therapeutic range may have less benefit in terms of stroke and systemic embolism with a novel drug than with warfarin.16 Efforts have also been made to improve control of time in therapeutic range, such as self monitoring of warfarin, and this approach may be non-inferior to the novel oral anticoagulants.17

Limitations

As with similar analyses,2 3 indirect comparison analyses have inherent limitations which we previously recognised in our analysis of the whole trial population.2 Because selection into each of the trials was different, this method of comparison cannot necessarily be considered straightforward, and comparisons of this kind can be considered to be only hypothesis generating and the basis for a head to head trial.

In the absence of head to head trials, this statistical method is one technique for comparing different drugs. Our analysis minimises trial population heterogeneity by particularly focusing on the secondary prevention cohort, with a secondary indirect comparison analysis of the primary prevention cohort. We have also compared marketed and approved doses of the various drugs. Some of the differences seen for dabigatran 110 mg twice daily may simply reflect the lower dose compared with the 150 mg twice daily dose, but the RE-LY trial (as opposed to the other trials) prospectively tested the two doses of dabigatran as separate intervention arms of the three arm randomised trial versus warfarin (although the dabigatran doses were given in blinded manner). Rivaroxaban and apixaban had dose adjustments based on certain clinical criteria (see supplementary table A), and the lower doses were given to only a minority of the whole trial population and were not tested as a separate trial intervention arm. Finally, although the phase III clinical trials used warfarin as the comparator, warfarin is not used (or even marketed) in many countries in Europe now. Phenprocoumon is more commonly used in these countries, and the efficacy of these new drugs compared with phenprocoumon has not yet been shown, which may be a question for future research.

Conclusion

This analysis suggests that for secondary prevention of stroke in atrial fibrillation, apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran have broadly similar efficacy for the main endpoints, although the endpoints of haemorrhagic stroke, vascular death, major bleeding, and intracranial bleeding were less common with dabigatran 110 mg twice daily than with rivaroxaban. For primary prevention, the three drugs showed some differences in efficacy and bleeding.

What is already known on this topic

Three novel oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban) have completed large phase III clinical trials for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation with warfarin as the comparator

Data from the secondary prevention subgroups (that is, patients with previous stroke) from these trials have recently been published

No head to head trials have directly compared these novel anticoagulants against each other

What this study adds

In indirect comparison analysis for secondary prevention, apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran had broadly similar efficacy for stroke/systemic embolism, ischaemic stroke, and all-cause mortality

Haemorrhagic stroke, vascular death, major bleeding, and intracranial bleeding were less common with dabigatran 110 mg twice daily than with rivaroxaban.

For primary prevention, the three drugs showed some differences in relation to efficacy and bleeding

Contributors: GYHL provided the idea for the article and contributed to drafting and subsequent revisions. LHR and TBL contributed to manuscript drafts and revisions. TG and FS did the analyses and contributed to manuscript revisions. LHR and GYHL are the guarantors.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; GYHL has served as a consultant for Bayer, Astellas, Merck, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, BMS/Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim and has been on the speaker bureau for Bayer, BMS/Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Sanofi; TBL and LHR have served as speakers for BMS/Pfizer and Boehringer Ingelheim; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;345:e7097

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

References

- 1.Potpara TS, Lip GY, Apostolakis S. New anticoagulant treatments to protect against stroke in atrial fibrillation. Heart 2012;98:1341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lip GY, Larsen TB, Skjøth F, Rasmussen LH. Indirect comparisons of new oral anticoagulant drugs for efficacy and safety when used for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:738-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mantha S, Ansell J. An indirect comparison of dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban for atrial fibrillation. Thromb Haemost 2012;108:476-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W, et al, for the ROCKET-AF Investigators. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;365:883-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, et al, for the RE-LY Steering Committee and Investigators. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1139-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Reilly PA, Wallentin L, for the Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy Investigators. Newly identified events in the RE-LY trial [letter]. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1875-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, Lopes RD, Hylek EM, Hanna M, et al, for the ARISTOTLE Committees and Investigators. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;365:981-92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diener HC, Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Wallentin L, Reilly PA, Yang S, et al, for the RE-LY Study Group. Dabigatran compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and previous transient ischaemic attack or stroke: a subgroup analysis of the RE-LY trial. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:1157-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hankey GJ, Patel MR, Stevens SR, Becker RC, Breithardt G, Carolei A, et al, for the ROCKET AF Steering Committee Investigators. Rivaroxaban compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack: a subgroup analysis of ROCKET AF. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:315-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Easton JD, Lopes RD, Bahit MC, Wojdyla DM, Granger CB, Wallentin L, et al, for the ARISTOTLE Committees and Investigators. Apixaban compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack: a subgroup analysis of the ARISTOTLE trial. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:503-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, Walter SD. The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50:683-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song F, Loke YK, Walsh T, Glenny AM, Eastwood AJ, Altman DG. Methodological problems in the use of indirect comparisons for evaluating healthcare interventions: survey of published systematic reviews. BMJ 2009;338:b1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holnloser SH, Oldgren J, Yang S, Wallentin L, Ezekowitz M, Reilly P, et al. Myocardial ischemic events in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with dabigatran or warfarin in the RE-LY(Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy) trial. Circulation 2012;125:669-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wan Y, Heneghan C, Perera R, Roberts N, Hollowell J, Glasziou P, et al. Anticoagulation control and prediction of adverse events in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2008;1:84-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallagher AM, Setakis E, Plumb JM, Clemens A, van Staa TP. Risks of stroke and mortality associated with suboptimal anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation patients. Thromb Haemost 2011;106:968-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallentin L, Yusuf S, Ezekowitz MD, Alings M, Flather M, Franzosi MG, et al, for the RE-LY Investigators. Efficacy and safety of dabigatran compared with warfarin at different levels of international normalised ratio control for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: an analysis of the RE-LY trial. Lancet 2010;376:975-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heneghan C, Ward A, Perera R, for the Self-Monitoring Trialist Collaboration. Self-monitoring of oral anticoagulation: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet 2012;379:322-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.