Abstract

The intricate, and often polarized, ingrowth walls of transfer cells (TCs) amplify their plasma membrane surface areas to confer a transport function of supporting high rates of nutrient exchange across apo-/symplasmic interfaces. The TC ingrowth wall comprises a uniform wall layer on which wall ingrowths are deposited. Signals and signal cascades inducing trans-differentiation events leading to formation of TC ingrowth walls are poorly understood. Vicia faba cotyledons offer a robust experimental model to examine TC induction as, when placed into culture, their adaxial epidermal cells rapidly (h) and synchronously form polarized ingrowth walls accessible for experimental observations. Using this model, we recently reported findings consistent with extracellular hydrogen peroxide, produced through a respiratory burst oxidase homolog/superoxide dismutase pathway, initiating cell wall biosynthetic activity and providing directional information guiding deposition of the polarized uniform wall. Our conclusions rested on observations derived from pharmacological manipulations of hydrogen peroxide production and correlative gene expression data sets. A series of additional studies were undertaken, the results of which verify that extracellular hydrogen peroxide contributes to regulating ingrowth wall formation and is generated by a respiratory burst oxidase homolog/superoxide dismutase pathway.

Keywords: Vicia faba, trans-differentiation, cell wall, cell wall peroxidase, hydrogen peroxide, respiratory burst oxidase, transfer cell

Nutrient partitioning within plants is primarily regulated at sites of intense apo-/symplasmic nutrient exchange such as loading/unloading of vascular systems and loading of developing seeds.1 Space constraints at these sites necessitate high nutrient fluxes per transport cell thus creating potential “transport bottlenecks” by substrate saturation of their membrane transporters. A striking solution to this problem has been the evolution of a cell design where plasma membrane surface areas are substantially amplified (up to 20x) by constructing intricately-invaginated ingrowth walls that form scaffolds to support amplified plasma membrane areas2 and hence accommodate high transport rates (e.g., see refs. 3, 4). These specialized cells, called transfer cells (TCs), are formed by trans-differentiating from a range of differentiated cell types. Their ingrowth walls are polarized to the direction of nutrient transport and comprise a uniform wall on which wall ingrowths (WIs) are deposited.2 Despite the key physiological significance of TCs in nutrient transport and plant productivity, the regulatory mechanisms directing assembly of their ingrowth walls are poorly understood.

We have explored regulation of ingrowth wall formation using Vicia faba cotyledons. Upon transfer to culture, their adaxial epidermal cells commence an immediate, rapid (h) and synchronous trans-differentiation program to form functional epidermal TCs, with a cell wall architecture equivalent to that of their abaxial counterparts that trans-differentiate in planta.5,6 Studies with the V. faba cotyledon system have discovered components of an epidermal-cell specific network of signaling molecules that regulate assembly of the ingrowth wall. The signaling cascade is instigated by a spontaneously-generated spike in intracellular auxin levels on cotyledon transfer to culture.7 The auxin spike induces an ethylene signal transduced through the Ethylene Insensitive 3 (EIN3) pathway8 antagonistically modulated by a converging hexokinase (HXK) pathway elicited by intracellular glucose.9 The regulatory influence of ethylene on ingrowth wall assembly is mediated, in part, through a burst in extracellular hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) production. The H2O2 signal activates cell wall biosynthesis and provides a positional cue directing polarized deposition of the uniform wall, the attenuation of which comprises WI formation.10 Findings presented in this Addendum confirm that extra- rather than intracellular produced H2O2 is the principal reactive oxygen species (ROS) driving TC trans-differentiation and that this ROS signal is generated by respiratory burst oxidase homologs (rbohs).

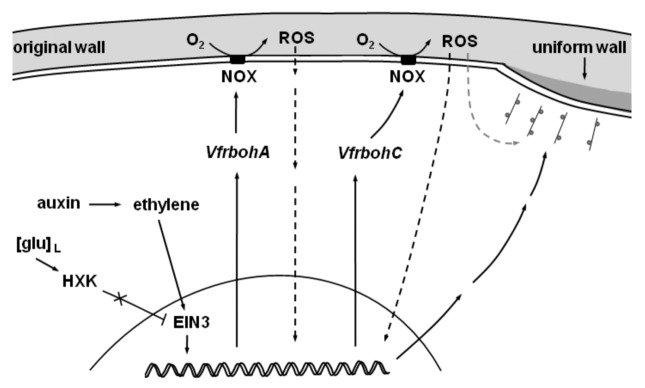

Our conclusion that extracellular H2O2 is a component of a signaling pathway regulating ingrowth wall formation relied on its inhibition by diphenyleneiodonium (DPI), a potent inhibitor of NADPH oxidases and other flavin-containing enzymes,11 and rescue from DPI inhibition by H2O2 supplementation.10 To remove any ambiguity introduced by possible dual DPI action on extra- and intracellular H2O2 synthesis,12 we explored the impact of selectively depleting extracellular H2O2 levels (see ref. 10) on uniform wall formation by culturing cotyledons on the extracellular Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD) inhibitor, diethyldithiocarbamate (DDC13), and ROS scavenger, ascorbic acid (AA14). These pharmacological treatments strongly suppressed extracellular H2O2 production.10 We repeated these experiments and monitored extra- and intracellular H2O2 production using acid loaded 3′,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) that forms a brown insoluble polymer on reacting with H2O2,15 Unfortunately AA interfered with DAB polymerization (data not shown). However, AA is unlikely to enter cotyledon epidermal cells as it will be ionized at pH 5.8 (pKa 4.2 and 11.6) in the MS medium. Thus we expect that AA selectively diminished extracellular ROS levels without impacting intracellular levels as was found for DDC (Fig. 1A vs B; C). In the presence of DDC, uniform wall thickness, and hence deposition, was reduced by 75 to 80% (Fig. 1C). In contrast, WI, and hence uniform wall, formation was unaffected (Fig. 1G) when intracellular H2O2 levels were depressed (Fig. 1D vs E, F; G) to a similar magnitude by DPI (data not shown), by culturing cotyledons on MS medium containing the antioxidants, butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) or flavone.16 These findings further demonstrate that extracellular H2O2 is the principal driver of the polarized assembly of the uniform wall on which WIs are deposited.

Figure 1. Cellular sources of (A - G), and biosynthetic pathway producing (H), H2O2 regulating ingrowth wall formation in adaxial epidermal cells of cultured cotyledons of Vicia faba. (A-G). Role of extra- (A - C) and intracellular (D - G) H2O2. Cotyledons were cultured for 15 h on MS medium without (A, D) or with (B) 1 mM DDC, (E) 500 µM BHA or (F) 1.3 mM flavone and thereafter processed as follows. (A - B; D - F) H2O2 was detected in outer periclinal walls and protoplasts of adaxial epidermal cells in 100 - 120 µm thick transverse sections of freshly-harvested cotyledons acid loaded (pH 3.5) with 10 mg/mL 3′,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB), contained within the MS medium. Upon reacting with H2O2, DAB forms a brown insoluble polymer. Sections were cut on a vibrotome. (C, G) Estimates of extra- and intracellular H2O2 levels derived from pixel densities of the cell wall (region outlined in A with white dashed line) and protoplasm (region outlined in A with black dashed line) scanned with ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/) and corrected for background. Cotyledons cultured on MS medium plus pharmacological reagents, but without DAB, were processed for (C) TEM to estimate thickness of the uniform wall or for (G) SEM to determine the percentages of adaxial epidermal cells containing WIs. Mean ± SE of four replicate cotyledons per treatment. ep, epidermal cell; sp, storage parenchyma cell. Bar for A, B = 30 µm, for D-f = 20 µm (H). Impact of 5 mM azide, a cell wall peroxidase inhibitor, on net efflux of H2O2. Cotyledons were cultured on MS medium for 1, 3 or 15 h. Thereafter, cotyledons were rinsed in several changes of distilled water before transferring each cotyledon, adaxial surface down, into a well of a 24 well plate containing Amplex Red solution with or without 5 mM sodium azide. After 15 min, the cotyledons were removed, re-rinsed in several changes of distilled water and the adaxial face of each cotyledon scanned for surface area determination by ImageJ software. Optical densities of the well solutions were determined at 560 nm spectrophometrically and amounts of H2O2 released into each solution determined from standard curves run concurrently. Net fluxes of H2O2 were estimated from the measurements described above. Mean ± SE of four replicate cotyledons per treatment (* p < 0.05 for treatment against control). For further procedural information, see ref. 10.

Extracellular H2O2 production by adaxial epidermal cells of cultured V. faba cotyledons is characterized temporally by two sequential oxidative bursts, the first peaking at 1 h followed by a second slower rise commencing at 3 h from the onset of cotyledon culture.10 Based on comparable inhibitions of H2O2 production by DPI and DDC, H2O2 production and expression of epidermal-specific Vfrbohs sharing similar temporal profiles and both being subject to ethylene regulation led us to conclude that the extracellular H2O2 signal was generated by a rboh-SOD pathway.10 However, DPI is known to inhibit H2O2 synthesis by not only rbohs, but also by haem-containing cell wall peroxidases.17 Furthermore, in some physiological contexts, cell wall peroxidases have been shown to contribute to bursts in extracellular H2O2 production (e.g., biotic stress responses18). This scenario could equally apply to generation of the H2O2 signal directing ingrowth wall formation in adaxial epidermal cells of V. faba cotyledons.10 We tested this possibility by determining responses of net H2O2 production to azide, an inhibitor of H2O2 synthesis by haem-containing cell wall peroxidases.17 To cover all possibilities we examined the impact of azide during the first (1 h) and second (15 h from the onset of cotyledon culture) bursts in extracellular H2O2 production as well as during the lag phase between bursts (3 h10). Consistent with the H2O2 signal being generated by plasma membrane rbohs alone, without any contribution by cell wall peroxidases, is supported by the absence of any azide inhibition of H2O2 production (Fig. 1H). Rather, cell wall peroxidases function to degrade the H2O2 signal as indicated by a diminishing azide stimulation of H2O2 production across cotyledon culture (Fig. 1H).

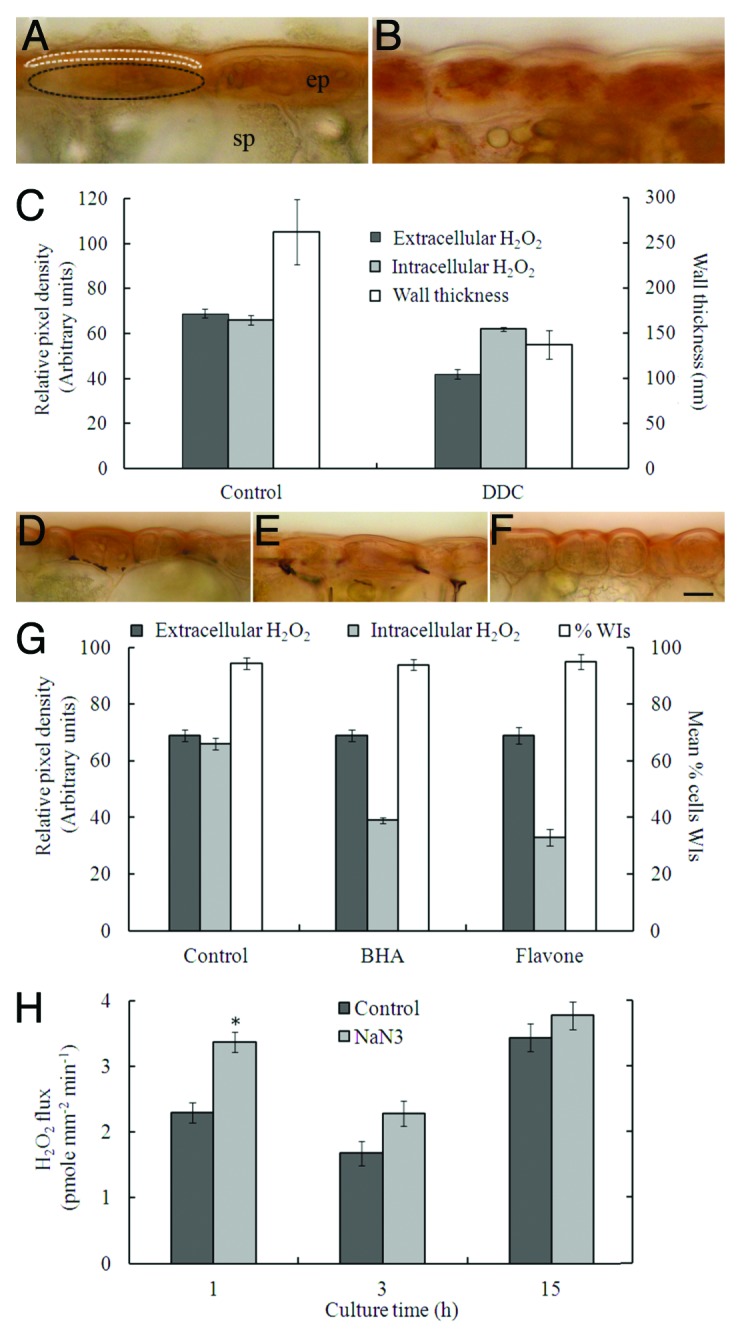

These findings, together with those reported earlier, are incorporated into a model describing identified signal and signaling pathways regulating ingrowth wall assembly during trans-differentiation of adaxial epidermal cells of cultured V. faba cotyledons to a TC morphology (Fig. 2). The trans-differentiation process is initiated by a rapid, cell-specific auxin-induced and auto-regulated burst in ethylene production, with subsequent activation of an ethylene-signaling cascade (Fig. Two and see refs. 7, 8). Glucose, sensed through HXK, acts as a gatekeeper of the ethylene signal by repressing ethylene biosynthesis and signaling.9 Coincident with the ethylene burst, intracellular glucose levels decline6 to a critical threshold at which repression on EIN3 abundance is released, promoting its accumulation in the presence of ethylene (Fig. Two and see ref. 9). As ethylene signaling proceeds, downstream targets of ethylene signaling are rapidly induced7 including expression of VfrbohA (Fig. Two and see ref. 10). We speculate that subsequent expression of VfrbohC is mediated by ROS produced by VfrbohA (Fig. 2) as found for ROS-dependent expression of rbohs during defense responses to pathogen attack (e.g., see ref. 18). The mechanism through which extracellular ROS regulates gene expression is unknown. We predict a signaling pathway is activated indirectly by ROS (Fig. 2), possibly via ROS reacting with an unidentified plasma membrane-bound sensor.19 Together, VfrbohA and VfrbohC generate the two consecutive and SOD-dependent bursts in extracellular H2O2 production (Fig. 1H; ref. 10), spatially restricted to the outer periclinal wall (Figs. 1A-C and 2;10). Acting through unknown signaling pathways, the extracellular H2O2 signal induces expression of cell wall biosynthetic machinery and provides the positional cue directing trafficking of this machinery to the outer periclinal wall to catalyze assembly of the polarized uniform wall (Figs. 1A-H and 2;10). Signals and signaling pathways regulating the subsequent re-organization of wall building machinery to orchestrate localized construction of WIs on the uniform wall is the subject of our ongoing investigations.

Figure 2. Model of signals and signaling pathways regulating uniform wall formation in adaxial epidermal cells of Vicia faba cotyledons. Auxin induces ethylene biosynthesis and lowering of intracellular glucose levels ([glu]L) removes the glu block on EIN3 allowing ethylene signaling to proceed. This leads to upregulated expression of VfrbohA that catalyzes a burst in extracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS). This induces VfrbohC expression through an unidentified signal transduction pathway (black broken arrow) to mediate a second burst in extracellular ROS production. The latter extracellular ROS signal acts through two unidentified signal transduction pathways. One induces expression of cell wall biosynthetic machinery (black broken arrow) and the other (gray broken arrow) provides the positional cue to direct polarized trafficking of wall building machinery to catalyze assembly of the polarized uniform wall.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joseph Enright for raising healthy experimental material. FA and H-M Z are grateful for the support of an Australian and University of Newcastle Postgraduate Award respectively.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- BHA

butylated hydroxyanisole

- DAB

3′,3′-diaminobenzidine

- DDC

diethyldithiocarbamate

- DPI

diphenyleneiodonium

- EIN3

Ethylene Insensitive 3

- ERFs

Ethylene Response Factors,

- HXK

hexokinase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- rboh

respiratory burst oxidase homologue

- SEM

scanning electron microscopy

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- TC

transfer cell

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/21320

References

- 1.Lalonde S, Tegeder M, Throne-Holst M, Frommer WB, Patrick JW. Phloem loading and unloading of amino acids and sugars. Plant Cell Environ. 2003;26:37–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2003.00847.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Offler CE, McCurdy DW, Patrick JW, Talbot MJ. Transfer cells: cells specialized for a special purpose. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2003;54:431–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amiard V, Demmig-Adams B, Mueh KE, Turgeon R, Combs AF, Adams WW., 3rd Role of light and jasmonic acid signaling in regulating foliar phloem cell wall ingrowth development. New Phytol. 2007;173:722–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maeda H, Sage TL, Isaac G, Welti R, Dellapenna D. Tocopherols modulate extraplastidic polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolism in Arabidopsis at low temperature. Plant Cell. 2008;20:452–70. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farley SJ, Patrick JW, Offler CE. Functional transfer cells differentiate in cultured cotyledons of Vicia faba L. seeds. Protoplasma. 2000;214:102–17. doi: 10.1007/BF02524267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wardini T, Talbot MJ, Offler CE, Patrick JW. Role of sugars in regulating transfer cell development in cotyledons of developing Vicia faba seeds. Protoplasma. 2007;230:75–88. doi: 10.1007/s00709-006-0194-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dibley SJ, Zhou Y, Andriunas FA, Talbot MJ, Offler CE, Patrick JW, et al. Early gene expression programs accompanying trans-differentiation of epidermal cells of Vicia faba cotyledons into transfer cells. New Phytol. 2009;182:863–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou Y, Andriunas F, Offler CE, McCurdy DW, Patrick JW. An epidermal-specific ethylene signal cascade regulates trans-differentiation of transfer cells in Vicia faba cotyledons. New Phytol. 2010;185:931–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andriunas FA, Zhang H-M, Weber H, McCurdy DW, Offler CE, Patrick JW. Glucose and ethylene signalling pathways converge to regulate trans-differentiation of epidermal transfer cells in Vicia narbonensis cotyledons. Plant J. 2011;68:987–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andriunas FA, Zhang H-M, Xia X, Offler CE, McCurdy DW, Patrick JW. Reactive oxygen species form part of a regulatory pathway initiating trans-differentiation of epidermal transfer cells in Vicia faba cotyledons. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:3617–29. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gapper C, Dolan L. Control of plant development by reactive oxygen species. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:341–5. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.079079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quan L-J, Zhang B, Shi W-W, Li H-Y. Hydrogen peroxide in plants: a versatile molecule of the reactive oxygen species network. J Integr Plant Biol. 2008;50:2–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2007.00599.x. www.jipb.net [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delledonne M, Zeier J, Marocco A, Lamb C. Signal interactions between nitric oxide and reactive oxygen intermediates in the plant hypersensitive disease resistance response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13454–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231178298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foyer CH, Noctor G. Ascorbate and glutathione: the heart of the redox hub. Plant Physiol. 2011;155:2–18. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.167569. www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.110.167569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thordal-Christensen H, Zhang Z, Wei Y, Collinge D. Subcellular localization of H2O2 in plants. H2O2 accumulation in papillae and hypersensitive response during the barley powdery mildew interaction. Plant J. 1997;11:1187–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.11061187.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maxwell DP, Wang Y, McIntosh L. The alternative oxidase lowers mitochondrial reactive oxygen production in plant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8271–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolwell GP, Daudi A. Reactive oxygen species in plant-pathogen interactions. In: Reactive Oxygen Species in Plant Signaling, Signaling and Communication in Plants. del Río LA, Puppo A (eds), Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. 2009; pp 113-33. (Eds doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-00390-5_7) [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Brien JA, Daudi A, Finch P, Butt VS, Whitelegge JP, Souda P, et al. A peroxidase-dependent apoplastic oxidative burst in cultured Arabidopsis cells functions in MAMP-elicited defense. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:2013–27. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.190140. www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.111.190140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mittler R, Vanderauwera S, Suzuki N, Miller G, Tognetti VB, Vandepoele K, et al. ROS signaling: the new wave? Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16:300–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]