Abstract

ARF (alternative reading frame) is one of the most important tumor regulator playing critical roles in controlling tumor initiation and progression. Recently, we have demonstrated a novel and unexpected role for ARF as modulator of inflammatory responses.

Keywords: cancer, inflammation, macrophages, p19ARF, tumor suppressor

The innate immune response is one of the main mechanisms of defense used by our organism to protect against invading pathogens and prevent tumor progression. The ability to discriminate between the self and non-self is achieved by the immune system through different receptors which recognize specific molecules that are not found on basal conditions (healthy situation). A classic example of these receptors is the family of Toll-like receptors (TLR) that interact with conserved microbial structures called pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Ligand recognition by TLRs leads to the activation of intracellular signals that induce gene transcription and expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and effector molecules.1

In this complex scenario, tumor suppressors have recently emerged as novel regulators of innate antiviral host defense. This is the case of the ARF. ARF acts as a main sensor of hyperproliferative signals, being frequently inactivated in human cancers.2 Although, p53 activation was initially described as the major pathway induced by ARF, numerous evidences indicate ARF-independent effects including its antiviral function.3 However, relevance of ARF in host defense against other pathogens is still unknown. In Traves et al.4 we addressed whether ARF have any role in regulation of inflammatory response. To this end, we administered LPS to ARF−/− mice, showing that ARF deficiency conferred resistance to LPS-endotoxic shock. Additionally, we observed a significant inhibition of leukocyte recruitment in a model of thyoglicolate-induced peritonitis, suggesting a key role of ARF in the regulation of inflammatory responses. In order to investigate the mechanisms involved in this regulation, we explored the functional activity of ARF−/− macrophages after stimulation with different TLR ligands. We found that ARF deficiency severely impaired the production of inflammatory mediators such as nitric oxide, cytokines and chemokines. We further demonstrated that downstream signaling pathways induced upon TLR-stimulation such as MAPKs and NF-κB activation were inhibited in ARF-deficient macrophages. Importantly, we observed a decrease in IκBα degradation, p65 translocation from the cytosol to the nucleus and NF-κB DNA binding activity. Notably, inhibition of IκBα degradation was also reported in ARF deficient macrophages stimulated with vesicular stomatis virus in an independent study by García et al.3

Since several reports have described ARF regulation after virus infection, type I IFN treatment or expression of viral proteins,5 we determined whether TLR ligands regulate ARF expression. Surprisingly, no changes in ARF mRNA were detected after LPS treatment. This raises the question how ARF affects TLR-mediated cytokine induction. Previous works by Taura et al.6 showed that the tumor suppressor p53 regulates TLR3 expression. Therefore, we hypothesized that ARF might modulate TLRs expression. Importantly, a significative downregulation in the levels of TLR4 and TLR2 in basal conditions and lack of response to LPS treatment were observed in ARF-deficient macrophages. Moreover, the rescue of the inflammatory phenotype in ARF−/− cells after ARF overexpression supported positive regulation of TLRs by ARF. However, an open question remains to be answered: How ARF modulate TLR expression?. Since p53 is the primary target of ARF signaling, one possibility is that this transcription factor is the main regulator of TLR expression by ARF. Strikingly, overexpression of p53 did not alter levels and regulation of these receptors illustrating the p53-independent functions of ARF.

Recent evidences suggest that the transcription factor E2F1 plays a central role in the modulation of ARF functions. In addition, E2F1 has been described to physically interact with p65 subunit of NF-κB, inhibiting the formation of functional NF-κB (p65/p50)7,8 and in consequence acting as a negative regulator of inflammation. We found that basal levels of E2F1 were increased in ARF-deficient macrophages. Moreover, LPS-stimulation also induced E2F1 expression in these cells and enhanced physical interaction of p65 and E2F1 as coimmunoprecipitation studies revealed. Based on these findings we suggested that overexpression of E2F1 in ARF−/−cells leads to suppression of NF-κB-dependent genes explaining the attenuation of inflammatory response in non-TLR models such as TPA-induced edema and thyoglicolate-induced peritonitis. Furthermore, in silico identification of E2F consensus binding sites in TLRs promoters suggested that E2F1 may inhibit TLR expression.

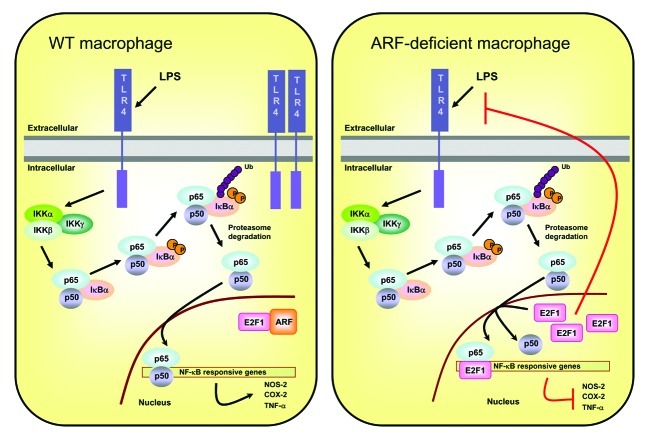

In summary, our findings provide evidence that ARF is a new regulator of inflammatory response and propose a potential mechanism by which ARF interacts with E2F1, regulating NF-κB signaling pathways and thereby inflammatory process (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Model of the regulation of inflammatory response by ARF. In normal cells, inflammatory stimuli induce NF-κB signaling pathways through the phosphorylation and subsequent ubiquitin-dependent degradation of IκBα by the 26S proteasome. Then, NF-κB translocates to the nucleus inducing target gene expression. ARF present in the nucleus, displays physical and functional interaction with E2F1 resulting in destabilization of E2F1 protein and activation of NF-κB. However, in the ARF-deficient macrophages, (p65/p50)NF-κB translocates to the nucleus but excessive E2F1 inhibits NF-κB by binding to its subunit p65 in competition with the heterodimeric partner p50. Moreover, excessive E2F1 may inhibit transcriptional expression of TLRs.

Although the role of tumor suppressors in innate immunity is still in early stage, our observations expand their functions in host cell defense against pathogens and contribute to better understand the link between tumor suppressors and inflammation.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/oncoimmunology/article/19948

References

- 1.Schnare M, Barton GM, Holt AC, Takeda K, Akira S, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors control activation of adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:947–50. doi: 10.1038/ni712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharpless NE, DePinho RA. The INK4A/ARF locus and its two gene products. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:22–30. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(99)80004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.García MA, Collado M, Muñoz-Fontela C, Matheu A, Marcos-Villar L, Arroyo J, et al. Antiviral action of the tumor suppressor ARF. EMBO J. 2006;25:4284–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Través PG, López-Fontal R, Luque A, Hortelano S. The tumor suppressor ARF regulates innate immune responses in mice. J Immunol. 2011;187:6527–38. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1004070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muñoz-Fontela C, García MA, Collado M, Marcos-Villar L, Gallego P, Esteban M, et al. Control of virus infection by tumour suppressors. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1140–4. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taura M, Eguma A, Suico MA, Shuto T, Koga T, Komatsu K, et al. p53 regulates Toll-like receptor 3 expression and function in human epithelial cell lines. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6557–67. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01202-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eymin B, Karayan L, Séité P, Brambilla C, Brambilla E, Larsen CJ, et al. Human ARF binds E2F1 and inhibits its transcriptional activity. Oncogene. 2001;20:1033–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka H, Matsumura I, Ezoe S, Satoh Y, Sakamaki T, Albanese C, et al. E2F1 and c-Myc potentiate apoptosis through inhibition of NF-kappaB activity that facilitates MnSOD-mediated ROS elimination. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1017–29. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00522-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]