Abstract

When food is plentiful, circadian rhythms of animals are powerfully entrained by the light-dark cycle. However, if animals have access to food only during their normal sleep cycle, they will shift most of their circadian rhythms to match the food availability. We studied the basis for entrainment of circadian rhythms by food and light in mice with targeted disruption of the clock gene Bmal1, which lack circadian rhythmicity. Injection of a viral vector containing the Bmal1 gene into the suprachiasmatic nuclei of the hypothalamus restored light-entrainable, but not food-entrainable, circadian rhythms. In contrast, restoration of the Bmal1 gene only in the dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus restored the ability of animals to entrain to food but not to light. These results demonstrate that the dorsomedial hypothalamus contains a Bmal1-based oscillator that can drive food entrainment of circadian rhythms.

The circadian timing system (CTS) exerts endogenous temporal control over a wide range of physiological and neurobehavioral variables, conferring the adaptive advantage of predictive homeostatic regulation (1). When food is freely available, light signals from the retina entrain circadian rhythms to the day-night cycle (2). However, when food is available only during the normal sleep period [restricted feeding (RF)], many of these rhythms are reset so that the active phase corresponds to the period of food availability (3, 4). In light entrainment, retinal ganglion cells that contain the photopigment melanopsin provide signals to neurons in the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) of the hypothalamus that generate circadian rhythms through a series of molecular transcriptional, translational, and posttranslational feedback loops (5). The SCN in turn synchronizes circadian rhythms in peripheral tissue clocks through synaptic and humoral outputs (5, 6). During RF, the SCN remains on the light cycle and SCN lesions do not prevent food entrainment, which suggests that another clock may supersede the SCN (3, 4, 7). Two recent studies have suggested that at least one food-entrainable clock may be located in the dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (DMH), but the importance of this clock for food entrainment has been disputed (3, 8-10).

The core components of the molecular clock include the activating transcription factors BMAL1 and CLOCK and the negative regulatory feedback elements encoded by the Per and Cry genes (11, 12). Bmal1 is the only circadian clock gene without a known functional paralog and hence the only one for which a single gene deletion causes a complete loss of behavioral and molecular rhythmicity (13). Because its gene product BMAL1 is a transcription factor that likely influences many downstream genes, Bmal1−/− mice also exhibit other physiological defects unrelated to the circadian defect (14), including progressive arthropathy, decreased locomotor activity levels and body mass, and a shortened life span (15-18).

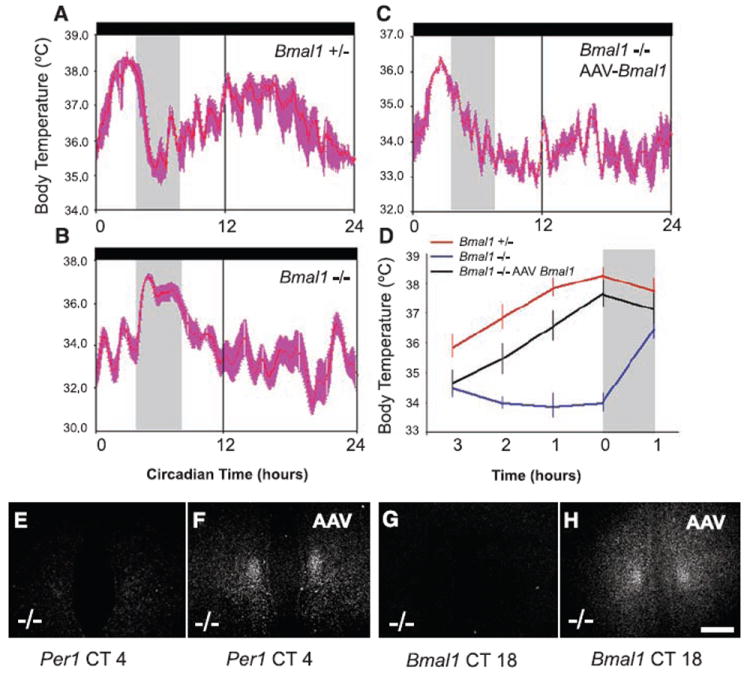

In this study, we used Bmal1−/− mice, which harbor a null allele at the Bmal1 locus (19). The circadian patterns of locomotor activity (LMA) and body temperature (Tb) were monitored by telemetry (Fig. 1, A to C, and fig. S2). As previously reported, these animals showed no circadian rhythms in a 12-hour-light/12-hour-dark (LD) cycle or constant darkness (DD) when given ad libitum (AL) access to food (Fig. 1B). We also attempted to entrain Bmal1−/− mice to a 4-hour window of RF during the normal sleep period for mice, under both LD [ZT4-8 (from 4 to 8 hours after light onset)] and DD [CT4-8 (from 4 to 8 hours after presumptive light onset)] conditions. In LD and DD conditions, wild-type (WT) and heterozygous littermates showed an elevation of Tb and LMA ~2 to 3 hours before food became available (Fig. 2, A and D, and fig S2). By contrast, Bmal1−/− mice did not show a comparable elevation in Tb or increase in LMA before the window of RF in DD; Tb and LMA were, however, markedly elevated in the Bmal1−/− mice after food presentation (Fig. 2, B and D, Fig. 3C, and fig. S2). In addition to the preprandial elevation in Tb under RF, WT and heterozygous littermates demonstrated a clear circadian Tb rhythm (Fig. 2A), whereas Bmal1−/− mice demonstrated a persisting ultradian Tb pattern throughout the remainder of the day (Fig. 2B). In DD conditions, Bmal1−/− mice occasionally showed periods of torpor (Tb below 31°C), which were distributed randomly across the circadian day. Consequently, the Bmal1−/− mice not only failed to show elevation of Tb or LMA in anticipation of the RF but often slept or were in torpor through the window of RF, requiring us to arouse them by gentle handling after presentation of the food to avoid their starvation and death during RF.

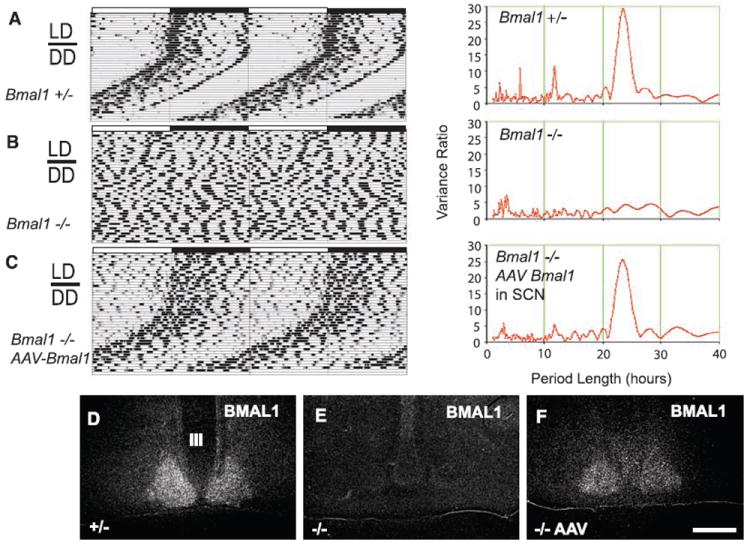

Fig. 1.

Bmal1 expression in SCN rescues circadian rhythms and light entrainment in Bmal1−/− mice. Representative body temperature (Tb) records (double-plotted actigrams) and period analyses for (A) Bmal1+/−, (B) Bmal1−/−, and (C) Bmal1−/− mice with AAV-BMAL1 injections into the SCN under both light-dark (LD) and constant darkness (DD) conditions with AL access to food. The power spectrum for period (right panel) shows a dominant frequency at 23.7 hours for both Bmal1 heterozygous littermates and mice with AAV-BMAL1 rescue in the SCN, and the lack of a ~24-hour harmonic in the Bmal1−/− mice. (D to F) Bmal1 mRNA expression (by in situ hybridization) in the SCN in (D) Bmal1+/− mice, (E) Bmal1−/− mice, and (F) after AAV-BMAL1 rescue by injection into the SCN (all ZT18). Scale bar, 100 μm.

Fig. 2.

Food entrainment of the Tb rhythm is rescued by AAV-BMAL1 injection into the DMH. Under DD conditions, Bmal1+/− and Bmal1−/− mice were placed under RF (food available CT4-8, gray vertical bar). (A) Bmal1+/− but not (B) Bmal1−/− mice demonstrated a clear rise in Tb ~2 to 3 hours before food availability under RF [(A) to (C) are waveforms showing mean ± SEM Tb on days 10 to 14 of RF for an individual mouse]. (C) After bilateral injection of AAV-BMAL1 into the DMH of Bmal1−/− mice, there was a preprandial elevation in Tb, but not a circadian rise in Tb during the presumptive dark cycle (CT12-24) [compare (C) with (A)]. As seen in the summary data plot, during the 3-hour window preceding food availability in RF (D), Bmal1−/− mice with DMH AAV-BMAL1 injections (n = 4, black trace) showed a comparable preprandial elevation in Tb (mean ± SEM) to that of Bmal1−/+ mice (red trace), whereas noninjected Bmal1−/− mice (blue trace) showed no preprandial elevation in Tb; an increase in Tb occurred only after food presentation in the noninjected Bmal1−/− mice (gray bar in D is first hour of food availability). Under RF, Bmal1−/− mice demonstrated very low expression levels of Per1 mRNA (E) (CT4 shown) and no expression of Bmal1 mRNA at CT18 (G) (near-peak expression time in the heterozygote littermates) in the DMH. By contrast, after AAV-BMAL1 injection into the DMH (F and H), Bmal1−/− mice demonstrated robust Per1 expression in the DMH at CT4 (F) and Bmal1 expression at CT18 (H).

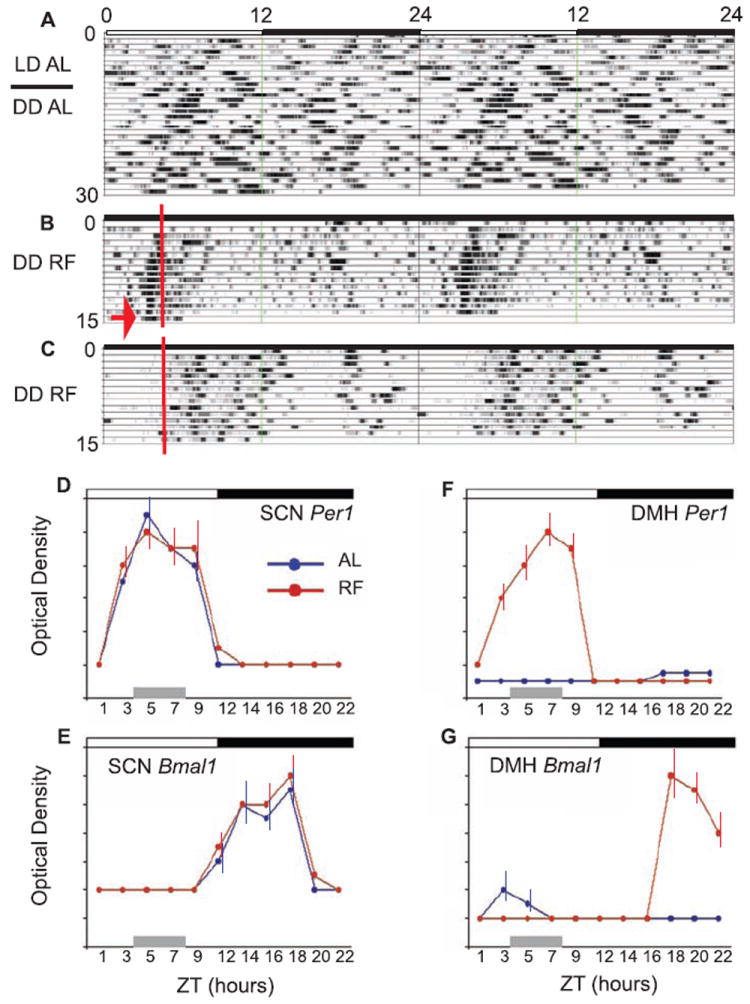

Fig. 3.

AAV-Bmal1 injection into the DMH rescues food entrainment but not light entrainment in Bmal1−/− mice. (A) A double-plotted actigram of Tb from a Bmal1−/− mouse after bilateral injections of AAV-Bmal1 into the DMH. These mice demonstrate the lack of entrainment to the light-dark (LD) cycle and persisting ultradian rhythmicity in constant darkness (DD) under AL feeding conditions (Fig. 1B). These same mice, however, demonstrated anticipation and entrainment (B) to a RF cycle (red line, food presentation) in DD conditions (arrow, last day, no food given). By contrast, noninjected Bmal1−/− mice (C) did not demonstrate anticipation or entrainment to the RF cycle. (D to G) Per1 and Bmal1 gene expression (optical density, mean ± SEM; n = 3 mice per time point) in WT mice across the circadian day under both AL and RF (all data 12:12 LD) at 2-hour intervals, except for a 3-hour interval between ZT9-12. (D) Per1 expression in the SCN showed a peak at ~ ZT6 under both AL and RF (gray bar, ZT4-8) conditions, demonstrating that the SCN remained phase-locked to the LD cycle during RF. (E) Bmal1 expression in the SCN showed a peak at ~ZT18 under both AL and RF, further indicating that the SCN remained synchronized to the LD cycle during RF. (F) Per1 expression in the DMH was undetectable at all ZT under AL; by contrast, Per1 expression was sharply up-regulated by RF, with a peak at ~ZT7-8. (G) Bmal1 expression in the DMH was also undetectable at all ZT (except very modest expression ~ZT 3-5) under AL, however, and similar to Per1, during RF Bmal1 demonstrated up-regulation with a peak at ~ ZT18.

After 14 days in this RF regimen, mice were killed to examine clock gene expression in the brain and were compared to mice that had been fed AL. As previously reported (8), WT animals with AL food showed peak expression of Per1 and Per2 mRNA at ZT5-6, and Bmal1 at ZT18-19 in the SCN (Fig. 3, D and E), but little or no expression at other hypothalamic sites. By contrast, WT animals under RF also showed no change in this expression pattern in the SCN (Fig. 3, D and E) but did show induction of Per1 and Per 2 at ~ZT3-9 (preceding, during, and after the RF window) in the DMH with peak expression levels at ZT7-8 (Fig. 3F). We also saw induction of Bmal1 mRNA in the DMH, with peak expression at ZT18-21 (Fig. 3G), consistent with neurons in the DMH showing induction of rhythmic expression of the entire suite of clock genes during RF. As previously reported for Per1 and Per2, Bmal1 gene expression was restricted to the compact region of the DMH. Finally, as expected in Bmal1−/− mice, no Bmal1 mRNA and very low expression levels of Per1 and Per2 were detected in the SCN and DMH under any feeding or lighting condition (Fig. 1E, Fig. 2, E to G, and fig. S4).

These results suggest that a BMAL1-based circadian clock may be induced in the DMH after starvation and refeeding to drive entrainment of circadian rhythms to the time of food availability. This hypothesis is consistent with previous studies showing that the DMH is a major recipient of direct and relayed input from the SCN and that it is important in relaying circadian signals for sleep-wake cycles, LMA, feeding, and corticosteroid rhythms to other brain systems (20). c-Fos expression in the DMH, but not in the SCN, is shifted to coincide with the activation of LMA and Tb during RF, and lesions of the DMH prevented entrainment of LMA, Tb, and sleep-wake cycles to RF [(3); also see (9, 10)].

To test the role of the DMH-inducible clock in entrainment of circadian rhythms, we attempted to rescue both light and food entrainment of circadian rhythms by injecting adeno-associated viral vectors (AAV, serotype 8) containing the Bmal1 gene (including both 5’ and 3’ promoter elements) (19) into the brains of Bmal1−/− mice. To test this construct, we first injected AAV-BMAL1 into the SCN. All mice with SCN injections (n = 6) (Fig. 1C), but none in which the injections missed the SCN (n = 16) or in which we injected a different AAV containing the gene for green fluorescent protein (GFP) into the SCN (n = 3), demonstrated entrainment of both LMA and Tb rhythms to a 12:12 LD cycle (Fig. 1C). When the mice were in DD conditions, this rhythm continued as a high-amplitude, free-running rhythm of 23.7 hours (Fig. 1C and fig. S1). Thus, focal bilateral injection of AAV-BMAL1 into the SCN of Bmal1−/− mice rescued the fundamental properties of the circadian oscillator, including light entrainment, free-running period, and rhythm amplitude. A previous study had shown that rescue of Bmal1−/− mice could be achieved by a transgene in which BMAL1 was placed under a constitutively active cytomegalovirus promoter (13). However, this gene construct, which was expressed continuously throughout the brain, produced a circadian period of ~22.7 hours, about 1 hour shorter than that of WT mice (13). By contrast, in our study, when we placed BMAL1 under its own promoter and restored this gene only to the SCN, the period of the circadian cycle was precisely the same as in WT animals (Fig. 1, A and C, right panel). Thus the expression of BMAL1 under its own promoter in the SCN alone is sufficient for recovery of light-entrained circadian rhythms. Our results also establish the SCN as sufficient for the generation of the circadian Tb rhythm, a point that has been in dispute (21).

On the other hand, similar to the mice with transgenic replacement of BMAL1 throughout the brain (14), locomotor activity levels in the animals with AAV-BMAL1 injections into the SCN remained significantly lower (P < 0.001) than those of WT and heterozygous littermate mice. Moreover, mice with AAV-BMAL1 injections into the SCN did not show improvement in any of the other physiologic deficits. Hence, these deficits are unlikely to be due to loss of circadian rhythmicity per se (14).

We next tested the animals with BMAL1 replacement in the SCN for their ability to entrain to a restricted temporal window of food availability. Previous studies had demonstrated that animals with lesions of the SCN could still entrain to food, suggesting that there was a food-entrainable oscillator elsewhere in the animals but not excluding participation of the SCN in intact animals (4, 7, 22). When animals with SCN injections of AAV-BMAL1 who had complete rescue of the light-entrained rhythms of LMA and Tb were placed into a food-restriction paradigm under DD conditions, we found that they maintained the rhythm that had been entrained by light (high-amplitude, free-running period of ~23.7 hours) and never showed an increase in LMA or Tb in anticipation of the food presentation (fig. S3). Hence, although a BMAL1-based clock is necessary to support food entrainment, restoration of clock function in the SCN alone is not able to rescue this behavior.

To test the hypothesis that the BMAL1-based clock induced in the DMH during restricted feeding might drive circadian entrainment, we performed stereotaxic bilateral delivery of AAV-BMAL1 (the same construct and vector as used in the SCN) into the DMH of Bmal1−/− mice. Mice who sustained bilateral DMH injections of the AAV-BMAL1 did not demonstrate entrainment to a 12:12 LD cycle or free-running rhythms of Tb or LMA in DD (Fig. 3A). By contrast, under conditions of food restriction in DD, they exhibited a clear anticipatory increase in Tb and LMA before food presentation (Fig. 2C and Fig. 3B). Each individual mouse showed very little day-to-day variation in the timing of the increase in Tb and LMA under DD (i.e., the phase angle of entrainment was stable). Finally, the increase in Tb and LMA before the predicted period of food presentation persisted during a 24-hour fast at the end of restricted feeding (arrow in Fig. 3B), demonstrating the circadian nature of the response.

In both our study and the study by Mieda et al. (8), clock gene expression in the DMH was largely restricted to cells in the compact part of the nucleus, which consists of small, closely packed neurons that are highly reminiscent of the SCN itself. These neurons appear mainly to have local connections with the adjacent output zones of the DMH (23), suggesting that the timing signal from the compact part of the DMH may impinge upon the same output neurons in the remainder of the DMH as are used to control light-entrained rhythms directed by the SCN. This relationship may explain how the DMH clock is able to override the SCN clock input during conditions of food entrainment in an intact animal. It is unlikely that feedback from the DMH alters activity in the SCN in any major way, because the SCN remains phase-locked to the LD cycle for many weeks during food entrainment (as long as the animals are not also hypocaloric). These observations also raise the interesting possibility that the DMH may form the neuroanatomic basis of the so-called methamphetamine-sensitive circadian oscillator (MASCO), which also operates independent of the SCN and does not entrain to light [for a review, see (24)].

Our data indicate that there is an inducible clock in the DMH that can override the SCN and drive circadian rhythms when the animal is faced with limited food availability. Thus, under restricted feeding conditions, the DMH clock can assume an executive role in the temporal regulation of behavioral state. For a small mammal, finding food on a daily basis is a critical mission. Even a few days of starvation, a common threat in natural environments, may result in death. Hence, it is adaptive for animals to have a secondary “master clock” that can allow the animal to switch its behavioral patterns rapidly after a period of starvation to maximize the opportunity of finding food sources at the same time on following days.

In an intact animal, peripheral oscillators in many tissues in the body, including the stomach and liver, as well as elsewhere in the brain, may contribute to food entrainment of circadian rhythms (25, 26). Consequently, it has been difficult to dissect this system by using lesions of individual components of the pathway (3, 9, 10). However, by starting with a genetically arrhythmic mouse and using focal genetic rescue in the brain, we have identified the SCN molecular clock as sufficient for light but not food entrainment of Tb and LMA rhythms in mice, and the DMH as sufficient for food but not light entrainment of circadian rhythms of Tb and LMA. These results demonstrate the power of viral-based gene replacement in the central nervous system to dissect complex neural functions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Q. Ha and M. Ha for technical work. Support was provided by U.S. Public Health Service grants HL60292, NS33987, NS051609, NS057119, and HL07901-08.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/320/5879/1074/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S4

References

References and Notes

- 1.Hastings MH, Reddy AB, Maywood ES. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:649. doi: 10.1038/nrn1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saper CB, Lu J, Chou TC, Gooley J. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:152. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gooley JJ, Schomer A, Saper CB. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:398. doi: 10.1038/nn1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stephan FK, Swann JM, Sisk CL. Behav Neural Biol. 1979;25:346. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(79)90415-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lowrey PL, Takahashi JS. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2004;5:407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.5.061903.175925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kramer A, et al. Science. 2001;294:2511. doi: 10.1126/science.1067716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stephan FK. Physiol Behav. 1989;46:489. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mieda M, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604189103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landry GJ, Simons MM, Webb IC, Mistlberger RE. Am J Physiol. 2006;290:6. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00874.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gooley JJ, Saper CB. J Biol Rhythms. 2008;22:479. doi: 10.1177/0748730407307810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gekakis N, et al. Science. 1998;280:1564. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng B, et al. Cell. 2001;105:683. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bunger MK, et al. Cell. 2000;103:1009. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00205-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDearmon EL, et al. Science. 2006;314:1304. doi: 10.1126/science.1132430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bunger MK, et al. Genesis. 2005;41:122. doi: 10.1002/gene.20102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laposky A, et al. Sleep. 2005;28:395. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimba S, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502383102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudic RD, et al. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online

- 20.Chou TC, et al. J Neuroscience. 2003;23:1069. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuller CA, et al. Am J Physiol. 1981;241:5. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1981.241.5.R385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krieger DT, Hauser H, Krey LC. Science. 1977;197:398. doi: 10.1126/science.877566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson RH, Canteras NS, Swanson LW. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1998;27:89. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiroshige T, Honma K, Honma S. Brain Res Bull. 1991;27:441. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(91)90139-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stokkan KA, et al. Science. 2001;291:490. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5503.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Damiola F, et al. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2950. doi: 10.1101/gad.183500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.