Abstract

RATIONAL

Fatty acids labeled with 18O at the carboxyl group, including oxidized species (FA18O), are a useful, low cost, and easy to prepare tool for quantitative and qualitative mass spectrometry (MS) analysis in biological systems. In addition, they are used to trace FA fate in metabolic pathways including FA re-esterification and lipid remodeling pathways. Although a rapid 18O exchange on FA18O in biological systems has been reported, the mechanism contributing to 18O exchange has not been fully evaluated. This gap of knowledge limits the use of FA18O as a standard for MS and complicate data interpretation for FA metabolism in biological systems.

METHODS

In the present study we have addressed a number of possible mechanisms for a rapid 18O exchange on prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) using rat plasma as a model. High performance liquid chromatography coupled with electro-spray ionization triple-quadrupole MS in the multiple reaction monitoring mode was used for quantification.

RESULTS

The major mechanism for a rapid 18O exchange on PGE218O in rat plasma is PGE2 processing with esterases, while FA re-esterification and non-enzymatic mechanisms do not significantly contribute to this phenomenon. In addition, we report a highly effective inhibition of 18O exchange with diethylumbelliferyl phosphate that can be used to stabilize FA18O in biological samples.

CONCLUSIONS

These data indicate the necessity to consider esterase activity when FA18O are used to study FA metabolism, and importance of esterase activity inhibition when FA18O are used as internal standards for MS analysis in biological systems. In addition, the results provide a rational for the development of new approaches to study esterase activities and affinity towards modified FA.

Keywords: Fatty acid metabolism, re-esterification, prostaglandins, mass spectrometry, HPLC

Introduction

Stable isotope labeled substrates are a powerful tool that allow for utilizing mass spectrometry (MS) in quantitative and qualitative analysis in biological systems. One of the tracers that has been used in MS are fatty acids, including oxidized species (FA), labeled with heavy 18O on carboxyl group (FA18O). The major advantage of FA18O is the ease and lost cost synthesis in an ordinary laboratory setup that allows for a fast preparation of large quantities of different FA18O, including modified FA [1]. One of the applications is utilizing FA18O as an internal or external standard for FA quantification including oxidized species [1–7] and structural identification of fatty acids [8–10]. In addition, FA18O might be used to trace FA fate in metabolic pathways, and to study kinetics of FA re-esterification and lipid remodeling pathways [11, 12]. Although a rapid 18O exchange on FA18O in biological systems has been reported [3, 11, 12], the mechanism contributing to 18O exchange has not been fully evaluated. This gap of knowledge might limit the use of FA18O as a standard for MS and complicate data interpretation for FA metabolism in biological systems. In the present study we have addressed a number of possible mechanisms for a rapid 18O exchange on prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) using rat plasma as a model. Our results indicate that the major mechanism for a rapid 18O exchange on PGE218O in rat plasma is PGE2 processing with esterases, while PGE2 re-esterification and non-enzymatic mechanisms do not significantly contribute to this phenomenon. This data provide important information for the development of new approaches to study esterase activities, especially if the esterase affinity towards modified FA is addressed. In addition, our data indicate that esterase activity should be considered when FA18O are used to study FA metabolism, and the necessity to inhibit esterase activity when FA18O are used as internal standards for MS analysis of biological matrix.

Methods

Animal Protocol

This study was performed according to the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication 80-23) and under an animal protocol approved by the IACUC at the University of North Dakota (Protocol #0806-1). The rat plasma was a pooled sample collected from Sprague Dawley rats using sodium heparin as an anticoagulant and was purchased commercially from Bioreclamation, LLC (Westbury, NY).

Chemicals

Water-18O, diethylumbelliferyl phosphate (DEUP) and Sigmacote® were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo). Porcine liver esterase was purchased from Lee Biosolutions (St. Louis, Mo). Deuterium labeled prostaglandin D2-17,17,18,18,19,19,20,20,20-d9 (PGD2d9), deuterium labeled prostaglandin E2-3,3,4,4-d4 (PGE2d4), prostaglandin E2-1-glyceryl ester (PGE2-Gly), and methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate (MAFP) were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). LC/MS/MS grade acetonitrile, water, methanol, and chloroform were from Fisher Scientific. All other chemicals of analytical or higher quality were purchased from VWR International (West Chester, PA)

Synthesis of Oxygen 18O labeled PGE2d4

PGE2d4 was labeled with 18O using porcine liver esterase to exchange the two oxygen atoms on the carboxylic acid with 18O from water-18O as previously described [4] with slight modifications. Briefly, porcine esterase (130 Units, 1mg) was dissolved in 250 μL water-18O (97% atom enrichment) and combined with 25 μg of PGE2d4 dissolved in 25 μL of methanol. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 hr. Acetone (0.5 mL) was added to precipitate the protein. Sodium chloride (2.5 mg) was added and the solution was acidified to pH 3.5 with formic acid. The labeled prostaglandin was then extracted using 0.5 mL CHCl3. The extract was dried under a stream of nitrogen and dissolved in ethanol. The percent of 18O into PGE2d4 (PGE218Od4) incorporation was determined using LC/MS/MS and was 91% for dual 18O labeled, 8% for mono 18O labeled, and below 1% for zero 18O labeled PGE2d4.

Kinetics studies

Stock solutions of each inhibitor and substrate were prepared in either DMSO (DEUP) or ethanol (MAFP and substrates). Rat plasma was diluted in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). Before each experiment, the inhibitor (DEUP or MAFP) was added to the plasma-PBS solution and pre-incubated for ten minutes. PGE2-Gly and PGE218Od4 were diluted in PBS and the reaction was started by adding the substrate-PBS solution to the rat plasma-PBS solution so the final concentrations were 20 ng/mL PGE2-Gly, 10 ng/mL PGE218Od4, and 10% rat plasma. The final volume of each reaction was 250 μL with less than 0.1% organic solvent. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C. The rate of 18O back exchange was calculated as the mass of PGE2 that lost one and two 18O labels per unit of time per plasma volume. The enzyme activity (ng/min/mL) towards PGE2-Gly was determined by measuring the amount of PGE2 released during the incubation time and dividing by incubation time and by the amount of plasma in the sample. For the IC50 calculation, the reaction rates were plotted against the decimal logarithm of inhibitor concentrations, and IC50 were determined from non-linear regression using GraphPad Prism 5 (Graphpad, San Diego, CA). The half life was calculated as ln2 divided by reaction constant.

Prostaglandin extraction and analysis

Prostaglandins were quantified using LC/MS/MS as previously described [13]. The prostaglandins were separated on a Luna C-18(2) column (3 μm, 100 Å pore diameter, 150 × 2.0 mm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) with a 0.5 μm stainless steel frit filter and a C-18 security guard cartridge (Phenomenex). The HPLC system consisted of an Agilent 1100 series LC pump with a wellplate autosampler (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) set at 4°C. The injection volume was 25 μL. The flow rate was 0.2 mL/min and the solvents used in the separation were 0.1 % formic acid in water (solvent A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (solvent B). Solvent B was increased from 20% to 42.5% over 50 min and was increased to 90% over the next 10.5 min. At 65.5 min solvent B was returned to 20% over 1 min to equilibrate the column for 14 min.

A quadrapole mass spectrometer (API3000; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with a TurbolonSpray ionization source was used for MS analysis. Instrument control, data acquisition, and data analysis were performed with Analyst software version 1.4.2 (Applied Biosystems). The mass spectrometer was operated in multiple reaction monitoring mode (MRM). The source was in negative ion electrospray mode at 350 °C, the electrospray voltage was -4250 V, the nebulizer gas was zero grade air at 8 L/min, and the curtain gas was ultrapure nitrogen at 11 L/min. The declustering potential was optimized for each analyte. The focusing potential was 2200 V, the entrance potential was 210 V, and the collision gas was 12 arbitrary units. The mass spectrometer was operated at unit resolution.

Prostaglandins were quantified using PGD2d9 as the internal standard. The mass transition used for MRM for non-labeled PGE2 was 351.2/189.1 that allows for its differentiation from endogenous isoprostanes [13], and for labeled PG we used more abundant 355.2/275.2 for PGE2d4, 360.3/280.2 for PGD2d9, 359.3/275.2 for PGE218O2d4, and 357.3/275.2 for PGE218O1d4.

ATP quantification

ATP was quantified using the ATP Determination Kit from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA) which is a firefly luciferase based assay with a limit of detection of 0.1 pmole ATP. To measure ATP in serum, 10 μL was added to 90 μL of the assay solution from the kit and the assay was performed according to manufacturer instructions. Luminescence at 560 nm was measured using a FlexStation III (Molecular Devices) plate reader.

Statistics

All statistical comparisons were calculated using one-way ANOVA analysis with Tukey post-test using GraphPad Prism 5 (Graphpad, San Diego, CA). Statistical significance was defined as <0.05. All values were expressed as mean ± SD.

Results and Discussion

A rapid 18O exchange during prostaglandin (PG) F2α18O incubation with human plasma has been previously reported [3]. Thus, we used plasma as a model system to address mechanisms contributing to 18O back exchange on FA. In the first set of experiments, we measured kinetics for 18O back exchange on PGE218O in rat plasma. Because of a high rate for 18O back exchange, we used a 10 fold dilution of rat serum with PBS (pH=7.4), and limited the incubation time to 60 min. In order to differentiate exogenous PGE2 that loses both 18O on carboxyl group during incubation from endogenous PGE2 found in plasma, we used dual labeled PGE2 with the 18O label at the carboxyl group, and 2H label on radical. The rate of 18O back exchange of PGE218Od4 with 16O from water was calculated as an amount of PGE2 that lost one or two 18O. Consistent with high rates reported for PGF2α18O [3], the rate for PGE218O exchange was very high (2.09±0.08 ng/min/mL) with reaction rate constant k=0.84 min−1. The calculated half life of oxygen on PGE2 carboxyl group was relatively short and equals 0.82±0.11 min.

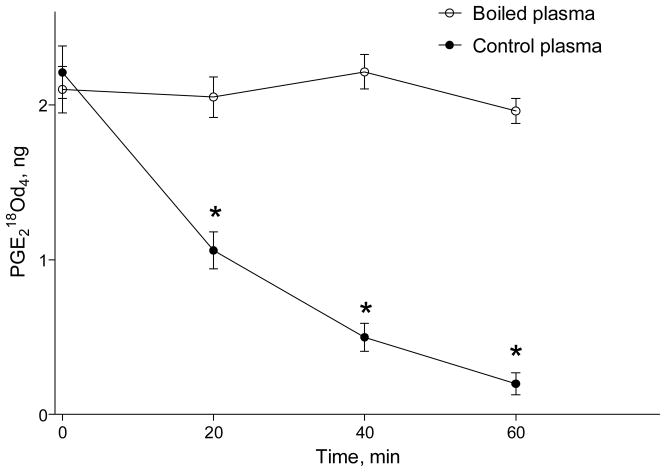

Next, we tested if non-enzymatic mechanisms contribute for a rapid 18O exchange on PGE218O in rat plasma. To test non-enzymatic mechanism, 10% rat plasma in PBS (pH=7.4) was boiled for 10 min in a closed container to heat denature proteins. As indicated in the Figure 1, there was no detectable 18O loss from PGE218O in boiled plasma, indicating that non-enzymatic, including albumin-catalyzed, mechanisms do not contribute to the 18O back exchange.

Figure 1.

Heat denaturing of plasma proteins prevents oxygen exchange on PGE2 carboxyl group.

Rat plasma (10% in PBS, pH=7.4) was boiled for 10 min in closed container to heat denature proteins. Two hundred fifty μL of boiled or control (not-boiled) plasma was incubated with 2 ng PGE218O at 37°C, and PG were extracted and analyzed using LC-MS as described in the Methods section. Results are mean ± SD, n=3.

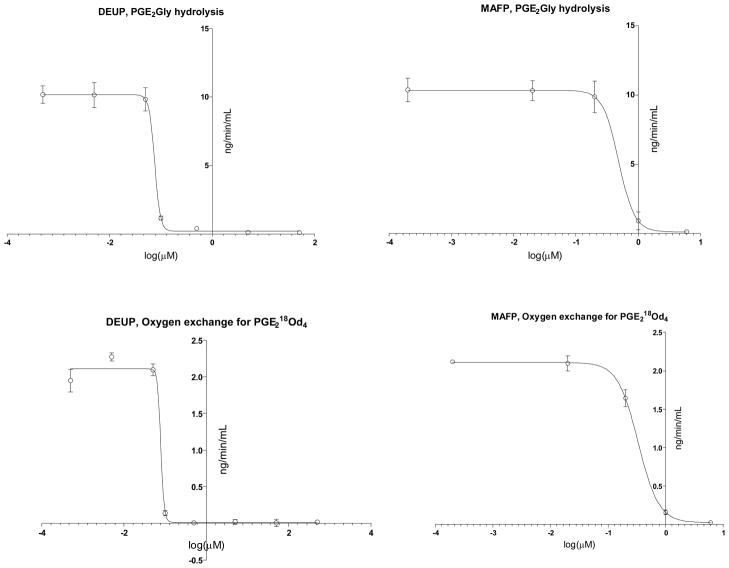

Because esterases are used for FA18O preparation by oxygen exchange with H218O [1–12], we next thought that esterases present in rat plasma might catalyze 18O exchange on PGE218O. The mechanism for esterase catalyzed oxygen exchange has been previously discussed [3]. To test this hypothesis, we used two different substrates: PGE218O and PGE2-1-glyceryl ester (PGE2Gly) and compared IC50 of esterase inhibitors for both substrates (Fig. 2). The calculated IC50 are presented in the Table 1. Both inhibitors tested, DEUP (esterase inhibitor [14–16]) and MAFP (serine dependent hydrolase inhibitor [17, 18]), completely inhibited 18O exchange and PGE2Gly with the same IC50 values, indicating that both reactions might be catalyzed by the same enzymes belonging to the esterase class.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of oxygen exchange and PGE2-glyceryl ester hydrolysis by DEUP and MAFP.

Two ng of prostaglandin E2 labeled with 18O at the carboxyl group (PGE218Od4, lower panel), and PGE2-1-glyceryl ester (PGE2Gly, upper panel) were incubated for 20 min at 37°C with 10% rat plasma in PBS (10%, pH=7.4, 250 mL total incubation volume) in the presence of different concentrations of diethylumbelliferyl phosphate (DEUP, esterase inhibitor) and methyl-arachidonoyl-fluorophosphate (MAFP, serine dependent hydrolase inhibitor). At the end of incubation, PG were extracted and analyzed using LC-MS as described in the Methods section. The rate of 18O back exchange from PGE218Od4 with 16O from water was calculated as an amount of PGE2 that lost one or two 18O. Results are mean ± SD, n=3.

Table 1.

IC50 values for inhibitors of oxygen exchange and PGE2-glyceryl ester hydrolysis hydrolysis

| Substrate used | Inhibitor, IC50, μM | |

|---|---|---|

| MAFP | DEUP | |

| Oxygen exchange for PGE218Od4 | 0.334±0.081 | 0.078±0.023 |

| PGE2Gly | 0.484±0.076 | 0.076±0.012 |

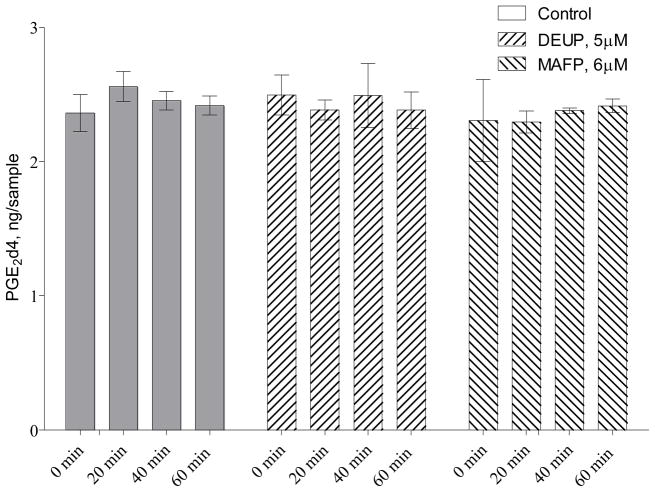

Finally, we addressed the role of a re-esterification mechanism in 18O exchange. According to the Fisher esterification mechanism, each cycle of esterification-hydrolysis (re-esterification) randomly exchanges one of the labeled oxygen atoms on carboxyl group of carboxylic acid on the oxygen from water. This mechanism has been previously applied to study re-esterification of FA and lipid remodeling [11, 12]. Because re-esterification cycle associated with oxygen exchange has been described for a number of different FA [19–22], we hypothesized that re-esterification contributes to the oxygen exchange on the PGE218O in rat plasma. Because esterification of the released free FA requires the energy of ATP [23], we measured ATP levels in rat plasma. Consistent with previous reports [24, 25], we found low but detectable ATP levels in rat plasma equal to 21.5±5.5 nM, that provides the possibility for a re-esterification mechanism. To further evaluate this mechanism, we measured the levels of labeled PGE2d4 during incubation with plasma in the presence of esterase inhibitors that inhibited 18O exchange (Table 1). Esterase inhibition is expected to inhibit hydrolysis of FA esters without altering the esterification reaction. Thus, if re-esterification contributes to 18O exchange, esterase inhibition should result in decreased free PG levels with increased esterified PG. As indicated in the Figure 3, the PGE2d4 levels were unchanged during incubation with or without esterase inhibitors, indicating that re-esterification does not contribute to oxygen exchange. This is important because this data indicate that oxygen exchange might not be associated with re-esterification cycle, and esterase activity should be considered in oxygen exchange experiments.

Figure 3.

Exogenous prostaglandin content is not changed during incubation with rat plasma

Deuterium labeled prostaglandin E2 (PGE2d4, 2ng) was incubated with rat plasma (10% in PBS, pH=7.4, 250 mL total incubation volume) at 37°C in the presence of diethylumbelliferyl phosphate (DEUP, 5 μM) and methyl-arachidonoyl-fluorophosphate (MAFP, 6 μM). At the indicated incubation times, PG were extracted and analyzed using LC-MS as described in the Methods section. Results are mean ± SD, n=3. * indicates statistically different values as compared to boiled plasma.

Together, our data provide evidence that oxygen exchange on FA18O might represent plasma esterase activity, and provides a rational for the development of new approaches to study esterase activities, especially if the esterase affinity towards modified FA is addressed. This might be of interest because of the ease and low cost for FA18O synthesis. In addition, our data indicate that esterase activity should be considered when FA18O are used to study FA metabolism, and the necessity to inhibit esterase activity when FA18O are used as internal standards for MS analysis of biological matrix.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant 5R21NS064480-02 (M.Y.G.), and the National Institutes of Health-funded Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE) Mass Spec Core Facility Grant 5P20RR017699.

List of Abbreviations

- DEUP

diethylumbelliferyl phosphate

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- FA18O

fatty acids labeled with 18O at the carboxyl

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- IC50

half maximal inhibitory concentration

- LC

liquid chromatography, MS, mass spectrometry

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PGD2d9

prostaglandin D2-17,17,18,18,19,19,20,20,20-d9

- PGE218Od4

a mixture of prostaglandin E2-1,1-18O-3,3,4,4-d4 (91%) and prostaglandin E2-1-18O-3,3,4,4-d4 (9%)

- PGE2d4

prostaglandin E2-3,3,4,4-d4

References

- 1.Murphy RC, Clay KL. In: Methods in Enzymology. James AM, editor. Vol. 193. Academic Press; 1990. p. 338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li H, Lawson JA, Reilly M, Adiyaman M, Hwang S-W, Rokach J, FitzGerald GA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:13381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pickett WC, Murphy RC. Analytical Biochemistry. 1981;111:115. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westcott JY, Clay KL, Murphy RC. Biological Mass Spectrometry. 1985;12:714. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200121208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehmann WD, Stephan M, Fürstenberger G. Analytical Biochemistry. 1992;204:158. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hishinuma T, Nakamura H, Itoh K, Ohyama Y, Ishibashi M, Mizugaki M. Prostaglandins. 1995;49:239. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(95)00016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerwin JL, Wiens AM, Ericsson LH. Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 1996;31:184. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(199602)31:2<184::AID-JMS283>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watson AD, Subbanagounder G, Welsbie DS, Faull KF, Navab M, Jung ME, Fogelman AM, Berliner JA. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:24787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.24787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moe MK, Strøm MB, Jensen E, Claeys M. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2004;18:1731. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hankin JA, Wheelan P, Murphy RC. Archives of Biochemistry & Biophysics. 1997;340:317. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.9921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmid PC, Johnson SB, Schmid HH. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266:13690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuwae T, Schmid PC, Schmid HHO. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Lipids and Lipid Metabolism. 1997;1344:74. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(96)00135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brose SA, Thuen BT, Golovko MY. Journal of Lipid Research. 2011;52:850. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D013441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrison EH, Bernard DW, Scholm P, Quinn DM, Rothblat GH, Glick JM. Journal of Lipid Research. 1990;31:2187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kellner-Weibel G, McHendry-Rinde B, Haynes MP, Adelman S. Journal of Lipid Research. 2001;42:768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gocze PM, Freeman DA. Cytometry. 1994;17:151. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990170207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balsinde J, Dennis EA. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:6758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.6758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Petrocellis L, Melck D, Ueda N, Maurelli S, Kurahashi Y, Yamamoto S, Marino G, Di Marzo V. Biochemical & Biophysical Research Communications. 1997;231:82. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golovko MY, Fargeman NJ, Cole NB, Castagnet PI, Nussbaum RL, Murphy EJ. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8251. doi: 10.1021/bi0502137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Golovko MY, Rosenberger TA, F‘rgeman NJ, Feddersen S, Cole NB, Pribill I, Berger J, Nussbaum RL, Murphy EJ. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6956. doi: 10.1021/bi0600289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Golovko MY, Rosenberger TA, Feddersen S, F‘rgeman NJ, Murphy EJ. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2007;101:201. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rapoport SI, Chang MCJ, Spector AA. Journal of Lipid Research. 2001;42:678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamashita A, Sugiura T, Waku K. Journal of Biochemistry. 1997;122:1. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hara N, Yamada K, Shibata T, Osago H, Tsuchiya M. PLoS ONE. 2011:6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gennady YG. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 2008;1783:673. [Google Scholar]