Abstract

Objective

This study examined whether childhood sexual abuse predicts initiation of injection drug use in a prospective cohort of youth.

Method

From October 2005 to November 2010, data were collected from the At Risk Youth Study (ARYS), a prospective cohort study of street-involved youth in Vancouver, Canada. Inclusion criteria were age 14-26 years, no lifetime drug injection, and non-injection drug use in the month preceding enrollment. Participants were interviewed at baseline and semiannually thereafter. Cox regression was employed to identify risk factors for initiating injection.

Results

Among 395 injection-naïve youth, 81 (20.5%) reported childhood sexual abuse. During a median follow-up of 15.9 months (total follow-up 606.6 person-years), 45 (11.4%) youth initiated injection drug use, resulting in an incidence density of 7.4 per 100 person-years. In univariate analyses, childhood sexual abuse was associated with increased risk of initiating injection (unadjusted hazard ratio [HR], 2.38; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.29–4.38; p=0.006), an effect that persisted in multivariate analysis despite adjustment for gender, age, Aboriginal ancestry and recent non-injection drug use (adjusted HR, 2.71; 95% CI, 1.42–5.20; p=0.003).

Conclusion

Childhood sexual abuse places drug users at risk for initiating injection. Addiction treatment programs should incorporate services for survivors of childhood maltreatment.

MeSH terms: child abuse, sexual, drug abuse, adolescent, cohort studies

1. Introduction

Injection drug use clearly places individuals at high risk of acquiring potentially fatal blood-borne pathogens such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV), and of experiencing other harms such as overdose (US Public Health Service, 1997; Des Jarlais and Friedman, 1987). The risk for becoming infected is especially high during the period immediately following the initiation of injection (Garfein et al., 1996; Roy et al., 2009). Survey-based studies of drug users have inquired retrospectively about individual and environmental factors associated with injection, revealing a number of factors more common among those who have ever injected compared to those who have not. Such factors include parental substance use (Martinez et al., 1998), familial dysfunction (Martinez et al., 1998), early onset of drug use (Sherman et al., 2005) and other early misconduct (Fuller et al., 2002; Tomas et al., 1990), forced institutionalization (Martinez et al., 1998; Roy et al., 2003), prior use of non-injection crack/cocaine, heroin or methamphetamine (Fuller et al., 2001; Hadland et al., 2010; Irwin et al., 1996; Sherman et al., 2005; Wood et al., 2008), homelessness (Martinez et al., 1998), violent victimization (Fuller et al., 2002), survival sex (Martinez et al., 1998), and high-risk peer networks and neighborhoods (Fuller et al., 2001).

With rare exception (Roy et al., 2003), however, these studies have tended to be limited by cross-sectional design, having recruited participants after they had already initiated injection drug use. Additionally, most of these studies recruited samples consisting predominantly of adult injection drug users (IDU), rather than young people. Conducting large, prospective cohort studies examining injection initiation among adolescents and young adults has proven difficult in many settings due to ethical concerns and difficulty locating and following at-risk youth populations, which in general are ‘hidden’ from traditional population-based sampling methods due to homelessness and extensive street involvement (Farrow et al., 1992). As a result, risk factors for transitioning to injection drug use among young people remain poorly elucidated.

One putative risk factor for initiating drug injection among youth is childhood sexual abuse, which is retrospectively reported by a large proportion of adult IDU (Ompad et al., 2005; Walton et al., 2011) and a well-established correlate of adult substance use in general (Molnar et al., 2001; Rounsaville et al., 1982). Cross-sectional studies of adult drug users suggest an association between lifetime sexual abuse and injection drug use (Cheng et al., 2006), with perhaps greater likelihood of early transition to drug injection during adolescence among those with a history of childhood sexual abuse (Holmes, 1997; Ompad et al., 2005). Prospective data of young adults following into middle adulthood demonstrate that those with a history of childhood maltreatment are more likely to use illicit drugs, to engage in polysubstance use, and to report substance use-related problems (Widom et al., 2006). Still, high quality studies drawing on prospective data from samples of youth are scarce (Roy et al., 2003), and the excess risk for initiating injection drug use conferred by childhood sexual abuse, if any, remains poorly quantified.

Reported prevalence of childhood sexual abuse among drug-using adolescents and young adults is high, with approximately one-third of youth disclosing prior abuse in several samples (Markowitz et al., 2011; Roy et al., 2004; Stoltz et al., 2007). The long-term mental health consequences of childhood sexual abuse are diverse and include depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder, some or all of which might in turn predispose to initiating drug injection (Browne and Finkelhor, 1986; Farrugia et al., 2011; Plotzker et al., 2007). Understanding which youth are at risk for transitioning to injection could help inform the allocation of already scarce public health efforts that seek to prevent the harms of injection drug use. In the present study, we hypothesize that history of childhood sexual abuse independently predisposes to initiating injection drug use among youth.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

The At Risk Youth Study (ARYS) followed a cohort of street-involved youth in Vancouver, Canada. Inclusion criteria for ARYS included: (1) aged 14 to 26 at the time of enrollment, and (2) use of an illicit drug other than or in addition to marijuana during the 30-day period prior to enrollment. The ARYS cohort relied on snowball sampling, with recruitment conducted in multiple neighborhoods in downtown Vancouver, including at night (Wood et al., 2006).

Following informed consent, all participants completed an extensive baseline interviewer-administered questionnaire pertaining to sociodemographic data, drug use behaviors, and lifetime history of childhood sexual abuse. They were then surveyed and examined for stigmata of injection drug use semiannually thereafter, with youth reporting on drug use patterns and other risk behaviors in the preceding six months. Participants were provided $20 CAN per visit as remuneration. ARYS was approved by the University of British Columbia/Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board.

From October 2005 to November 2010, 984 participants were recruited into the ARYS cohort, among whom 389 (39.5%) reported a prior history of injection. Those who had previously injected were more likely to be older and to have experienced childhood sexual abuse (both p<0.05), but otherwise did not differ according to gender or Aboriginal ancestry. Of the 595 youth who had not previously injected drugs at baseline, 395 (66.4%) returned for ≥1 follow-up visit and are included in the incidence analysis of injection drug use. Among the 395 youth included in the incidence analysis, the mean age of participants was 22.2 years (standard deviation [SD] = 2.7 years), and 269 (68.1%) youth were male and 105 (26.6%) were of Aboriginal ancestry. 81 (20.5%) youth reported childhood sexual abuse.

2.2. Dependent and independent variables

The primary outcome, or dependent variable, was self-reported initiation of injection drug use in the preceding six months. Participants were asked, “In the last six months have you used a needle to chip, fix or muscle even once? (Yes / No)” The sample in the present analysis was limited to all participants with no prior history of injection drug use at the time of enrollment. The primary independent variable of interest was self-reported history of childhood sexual abuse, based on earlier evidence from a study of street youth conducted elsewhere (Roy et al., 2003). At the baseline interview, participants were asked by a nurse in a separate, private interview in which confidentially was assured, “Before age 19, how many times were you sexually abused”, and participants were grouped into those with and without a prior history of abuse. An array of covariates was also examined, including gender, age (as a continuous variable), Aboriginal ancestry, high school education, self-reported sexual orientation, lifetime homelessness, lifetime incarceration, non-injection drug use in the preceding six months (including heroin, cocaine, crack, and crystal methamphetamine use), and sex work in the preceding six months.

2.3. Statistical analyses

Each of the variables listed above was initially examined in a series of bivariate associations with history of childhood sexual abuse. Next, applying Cox proportional hazards modeling, unadjusted hazard ratios for initiating injection drug use were computed for history of childhood sexual abuse and the other covariates. In addition, an interaction term examining prior sexual abuse according to gender as a risk factor for initiating drug injection was tested, which was not significant (data not shown); therefore, subsequent analyses were not stratified by gender. The final multivariate Cox regression model adjusted for gender, age, Aboriginal ancestry and recent drug use (i.e., non-injection use of heroin, cocaine or crystal methamphetamine in the preceding six months). Recent non-injection drug use was combined into a single variable to ensure parsimony, and a sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine whether this resulted in a different adjusted hazard ratio for the childhood sexual abuse, and it did not. Covariates included in the multivariate model were selected based on results of prior studies (Cheng et al., 2006; Fuller et al., 2001; Hadland et al., 2010; Irwin et al., 1996; Ompad et al., 2005; Sherman et al., 2005; Wood et al., 2008).

We performed all statistical analyses using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, North Carolina). Reported p values are two-sided and considered significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

Baseline characteristics of the 395 youth included in the incidence analysis of injection drug use are reported in Table 1 and compared with regard to history of childhood sexual abuse. Those with a history of childhood sexual abuse were more likely to be female (58.0% were female among those with history of childhood sexual abuse vs. 25.2% were female among those without history of childhood sexual abuse; p < 0.001), to be of Aboriginal ancestry (37.0% vs. 23.9%; p = 0.017), to identify as gay/lesbian/bisexual (34.6% vs. 10.5%; p < 0.001), and to have been recently involved in the sex trade (12.4% vs. 5.1%; p = 0.019). Of note, baseline rates of non-injection drug use did not differ between groups; the prevalence of non-injection heroin use among those with and without a history of childhood sexual abuse were, respectively, 14.8% vs. 13.4% (p = 0.737); of cocaine, 34.6% vs. 36.6% (p = 0.731); of crack, 48.2% vs. 45.5% (p = 0.675); and of crystal methamphetamine, 29.6% vs. 29.3% (p = 0.954).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of injection-naïve youth according to history of childhood sexual abuse in Vancouver, Canada, 2005-2010 (n = 395).

| Childhood Sexual Abuse | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Characteristic | Total (%) (n = 395) | No (%) (n = 314) | Yes (%) (n = 81) | p Value |

| Sociodemographic factors | ||||

| Female gender | 126 (31.9) | 79 (25.2) | 47 (58.0) | <0.001 |

| Mean age (SD) | 22.2 (2.7) | 22.2 (2.8) | 22.4 (2.8) | 0.415 |

| Aboriginal ancestry | 105 (26.6) | 75 (23.9) | 30 (37.0) | 0.017 |

| High school educationa | 194 (49.1) | 160 (51.0) | 34 (42.0) | 0.150 |

| Gay/lesbian/bisexual | 61 (15.4) | 33 (10.5) | 28 (34.6) | <0.001 |

| Ever homeless | 231 (58.5) | 179 (57.0) | 52 (64.2) | 0.242 |

| Ever incarcerated | 295 (74.7) | 241 (76.6) | 54 (66.7) | 0.063 |

| Drug use-related behaviors | ||||

| Non-injection heroin useb | 54 (13.7) | 42 (13.4) | 12 (14.8) | 0.737 |

| Non-injection cocaine useb | 143 (36.2) | 115 (36.6) | 28 (34.6) | 0.731 |

| Non-injection crack useb | 182 (46.1) | 143 (45.5) | 39 (48.2) | 0.675 |

| Non-injection crystal methamphetamine useb | 116 (29.4) | 92 (29.3) | 24 (29.6) | 0.954 |

| Mean age first drug use (SD) | 14.3 (2.6) | 14.4 (2.4) | 13.9 (3.3) | 0.898 |

| Sexual abuse history | ||||

| Sex workb | 26 (6.6) | 16 (5.1) | 10 (12.4) | 0.019 |

Prior completion of or current enrollment in high school

Denotes behavior in the preceding six months

During a median follow-up of 15.9 months per participant and a total study follow-up of 606.6 person-years, 45 (11.4%) of the 395 youth initiated injection, resulting in an incidence density of 7.4 per 100 person-years. Table 2 demonstrates crude incidence rates and unadjusted hazard ratios (HR) for select variables with regard to initiation of drug use. Table 3 demonstrates unadjusted and adjusted HR for these same variables, which were included in the multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model. Of note, the adjusted hazard ratio for childhood sexual abuse was not substantially affected by the combining together of recent non-injection drug use into a single variable; in a sensitivity analysis, when drugs were included as separate variables, the adjusted hazard ratio for childhood sexual abuse was 2.65 (95% CI, 1.37– 5.11; p = 0.004).

Table 2.

Crude incidence densities and unadjusted hazard ratios (HR) for factors related to initiation of injection drug use among youth in Vancouver, Canada, 2005-2010 (n = 395).

| Characteristic | Number of new injectors | Rate, per 100 person-years | HR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 14 | 2.4 | 1.03 (0.55 – 1.92) | 0.930 |

| Male | 31 | 2.4 | Reference | |

| Agea | ||||

| < 22 years | 24 | 5.9 | 1.96 (1.09 – 3.52) | 0.025 |

| ≥ 22 years | 21 | 3.0 | Reference | |

| Aboriginal ancestry | ||||

| Yes | 14 | 2.9 | 1.16 (0.62 – 2.19) | 0.637 |

| No | 31 | 2.3 | Reference | |

| Recent non-injection drug useb | ||||

| Yes | 41 | 6.2 | 2.63 (0.92 – 7.47) | 0.023 |

| No | 4 | 2.3 | Reference | |

| Childhood sexual abuse | ||||

| Yes | 16 | 4.4 | 2.38 (1.29 – 4.38) | 0.006 |

| No | 29 | 1.9 | Reference |

Included as dichotomous variable with median split for ease of interpretation (though treated as continuous variable in final multivariate model)

Denotes non-injection use of heroin, cocaine or crystal methamphetamine in the preceding six months

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) for factors related to initiation of injection drug use among youth in Vancouver, Canada, 2005-2010 (n = 395).

| Characteristic | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 1.03 (0.55 – 1.92) | 0.764 | 0.66 (0.32 – 1.35) | 0.256 |

| Age (per year younger) | 1.14 (1.03 – 1.26) | 0.010 | 1.11 (0.98 – 1.25) | 0.088 |

| Aboriginal ancestry | 1.16 (0.62 – 2.19) | 0.382 | 1.32 (0.67 – 2.59) | 0.424 |

| Recent non-injection drug usea | 2.63 (0.92 – 7.47) | 0.070 | 2.67 (0.92 – 7.70) | 0.070 |

| Childhood sexual abuse | 2.38 (1.29 – 4.38) | 0.006 | 2.71 (1.42 – 5.20) | 0.003 |

Denotes non-injection use of heroin, cocaine or crystal methamphetamine in the preceding six months

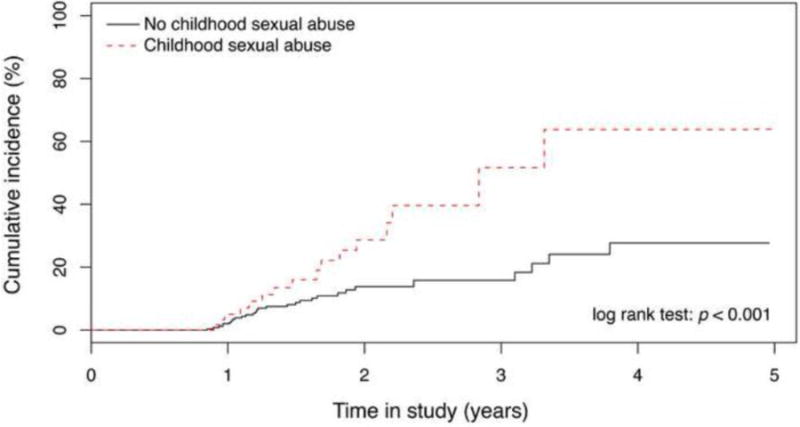

Figure 1 shows the cumulative incidence of initiating injection drug use according to history of childhood sexual abuse during follow-up (log-rank test, p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of initiation of injection drug among youth in Vancouver, Canada, 2005-2010 (n = 395).

4. Discussion

In this large, prospective cohort of adolescents and young adults, we observed that childhood sexual abuse placed youth at two to three times greater risk of initiating injection drug use. Notably, history of childhood sexual abuse was highly prevalent in our sample, with more than one-fifth of all participants reporting having been abused. We did not, however, observe any difference in risk for initiating drug injection between males and females according to history of childhood sexual abuse, a finding consistent with prior evidence that abuse may have equally damaging long-term effects for both genders (Dube et al., 2005).

Our results are consistent with prior cross-sectional data highlighting an association between prior sexual abuse and injection drug use among adults (Cheng et al., 2006). Indeed, adult IDU with a history of childhood sexual abuse frequently report transitioning to injection earlier (including during adolescence) than those without such a history (Holmes, 1997; Ompad et al., 2005). However, one of the only other prospective studies of youth injection initiation to date did not demonstrate increased risk for injection drug use among survivors of sexual abuse, although this study did not differentiate abuse during childhood from abuse later in life (Roy et al., 2003).

The pathways leading from childhood sexual abuse to risky drug use behaviors are likely to include a complex series of intermediate and more proximal factors (Ompad et al., 2005). Indeed, the factors may even differ among youth subpopulations, with heavily street-involved youth like those sampled in this study initiating injection drug use within an environment of homelessness, poverty, heavy non-injection drug use, and other important factors that may differ substantially from the environment in which other youth initiate injection drug use. Considered together, adverse childhood experiences – including sexual abuse, in addition to physical and emotional abuse/neglect, parental drug or alcohol abuse, parental incarceration, parental mental illness, domestic violence, or absence of one or both parents – have been correlated with a number of negative long-term outcomes, including subsequent alcohol use (Dube et al., 2006), illicit drug use (Dube et al., 2003), teen pregnancy (Hillis et al., 2004), and attempted suicide (Dube et al., 2001; Hadland et al., 2011), with depressive symptoms mediating many of these relationships. It is therefore possible that mental illness may indeed be a crucial intermediate in the pathway leading from childhood sexual abuse to later initiation of injection drug use. Complicating matters, childhood sexual abuse is often experienced as part of a ‘cluster’ of adverse childhood experiences, such as physical or emotional abuse/neglect, witnessing domestic violence, parental marital discord, or having a parent who is substance abusing, mentally ill, or criminally involved (Dong et al., 2003), all of which may have various contributions to risk. Future studies should therefore carefully examine the contribution of these various factors to initiating drug injection.

There are some limitations to the present study. First, our study recruitment employed extensive street-based outreach with snowball sampling. This method does not produce a truly random sample (Wood et al., 2006). However, the characteristics of our cohort are similar to those of other at-risk youth in western Canada (Miller et al., 2006; Ochnio et al., 2001). Also, because the sample was street-involved, they may not be fully representative of the general adolescent population at large. Second, our study relied heavily on self-report. Given that questions probed highly sensitive personal data, our results may have been affected by social desirability bias despite efforts to assure confidentiality (Briere, 1992). Recall bias may have also affected our results, particularly if those with heavier drug use patterns were more likely to recall a history of childhood sexual abuse (Widom et al., 1999). Finally, as outlined earlier, although our results show a strong relationship between childhood sexual abuse and initiating drug injection, our findings do not indicate which factors might be intermediates in this pathway.

5. Conclusion

In summary, we conclude that childhood sexual abuse is associated with substantially increased risk of initiating injection drug use among at-risk youth. These results highlight the dual need for programs that seek to prevent childhood maltreatment as well as those that mitigate the downstream consequences of sexual abuse during adolescence and young adulthood (Kerr et al., 2009). Indeed, adverse childhood experiences such as sexual abuse are likely to predispose to a range of risk behaviors and adverse health outcomes in adolescence and early adulthood that extend well beyond injection drug use (Anda et al., 2008; Chapman et al., 2004; Dube et al., 2005; Dube et al., 2003), and survivors of childhood abuse should remain a focus of research, policy and advocacy. A small body of evidence shows promise for home visit programs as well as population-level parenting education for preventing childhood abuse and neglect, while a reduction in adverse mental health outcomes has been demonstrated for sexually abused children with symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (MacMillan et al., 2009). Further developing these programs and ensuring wider implementation among at-risk youth may serve an important role in reducing injection drug use and its associated harms.

Highlights.

We examine whether childhood sexual abuse predicts injection drug use

We follow a prospective cohort of youth in Vancouver, Canada

More than one-fifth of youth report childhood sexual abuse

Abuse independently predicts risk for initiation of injection drug use

Addiction treatment should incorporate services for survivors of childhood abuse

Acknowledgments

We thank the At Risk Youth Study (ARYS) participants for their willingness to be included in the study, as well as current and past ARYS investigators and staff. We also acknowledge Deborah Graham, Tricia Collingham, Leslie Rae, Caitlin Johnston and Steve Kain for their assistance in research and administration. The corresponding author affirms that all who contributed significantly to the work are acknowledged here.

Role of Funding Source: This study was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (RO1 DA011591) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (HHP-67262). Dr. Kerr is additionally supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR). This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs program through a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Inner City Medicine which supports Dr Evan Wood. None of the aforementioned organizations had any further role in study design, the collection, analysis or interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: Dr. Montaner has received educational grants from, served as an ad hoc advisor to or spoken at various events sponsored by Abbott Laboratories, Agouron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc., Borean Pharma AS, Bristol–Myers Squibb, DuPont Pharma, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffmann–La Roche, Immune Response Corporation, Incyte, Janssen–Ortho Inc., Kucera Pharmaceutical Company, Merck Frosst Laboratories, Pfizer Canada Inc., Sanofi Pasteur, Shire Biochem Inc., Tibotec Pharmaceuticals Ltd. and Trimeris Inc.

Contributors: Drs. Hadland, Werb, Kerr, Montaner and Wood designed the study. Drs Hadland and Wood wrote the protocol. Dr. Hadland conducted the literature review and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Mr. Fu and Ms. Wang undertook statistical analyses with additional input from Dr. Hadland. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anda RF, Brown DW, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Giles WH. Adverse childhood experiences and prescription drug use in a cohort study of adult HMO patients. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:198. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J. Methodological issues in the study of sexual abuse effects. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1992;60:196–203. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne A, Finkelhor D. Impact of child sexual abuse: a review of the research. Psychol Bull. 1986;99:66–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. Journal of affective disorders. 2004;82:217–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Sherman SG, Srirat N, Vongchak T, Kawichai S, Jittiwutikarn J, Suriyanon V, Razak MH, Sripaipan T, et al. Risk factors associated with injection initiation among drug users in Northern Thailand. Harm Reduct J. 2006;3:10. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Friedman SR. HIV infection among intravenous drug users: epidemiology and risk reduction. AIDS. 1987;1:67–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Anda RF, Dube SR, Giles WH, Felitti VJ. The relationship of exposure to childhood sexual abuse to other forms of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction during childhood. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:625–39. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(03)00105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. JAMA. 2001;286:3089–96. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.24.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Whitfield CL, Brown DW, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Giles WH. Long-term consequences of childhood sexual abuse by gender of victim. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:430–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Chapman DP, Giles WH, Anda RF. Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: the adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics. 2003;111:564–72. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Miller JW, Brown DW, Giles WH, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and the association with ever using alcohol and initiating alcohol use during adolescence. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:444.e1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow JA, Deisher RW, Brown R, Kulig JW, Kipke MD. Health and health needs of homeless and runaway youth. A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 1992;13:717–26. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(92)90070-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrugia PL, Mills KL, Barrett E, Back SE, Teesson M, Baker A, Sannibale C, Hopwood S, Rosenfeld J, et al. Childhood trauma among individuals with co-morbid substance use and post traumatic stress disorder. Ment Health Subst Use. 2011;4:314–26. doi: 10.1080/17523281.2011.598462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller CM, Vlahov D, Arria AM, Ompad DC, Garfein R, Strathdee SA. Factors associated with adolescent initiation of injection drug use. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(1):136–45. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller CM, Vlahov D, Ompad DC, Shah N, Arria A, Strathdee SA. High-risk behaviors associated with transition from illicit non-injection to injection drug use among adolescent and young adult drug users: a case-control study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66:189–98. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfein RS, Vlahov D, Galai N, Doherty MC, Nelson KE. Viral infections in short-term injection drug users: the prevalence of the hepatitis C, hepatitis B, human immunodeficiency, and human T-lymphotropic viruses. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:655–61. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.5.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadland SE, Kerr T, Marshall BD, Small W, Lai C, Montaner JS, Wood E. Non-injection drug use patterns and history of injection among street youth. Eur Addict Res. 2010;16:91–8. doi: 10.1159/000279767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadland SE, Marshall BD, Kerr T, Qi J, Montaner JS, Wood E. Depressive symptoms and patterns of drug use among street youth. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48:585–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.009. Epub 2010 Dec 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis SD, Anda RF, Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA, Marks JS. The association between adverse childhood experiences and adolescent pregnancy, long-term psychosocial consequences, and fetal death. Pediatrics. 2004;113:320–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIV Prevention Bulletin: Medical Advice for Persons who Inject Illicit Drugs. Public Health Service, US Department of Health & Human Services; Washington, DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes WC. Association between a history of childhood sexual abuse and subsequent, adolescent psychoactive substance use disorder in a sample of HIV seropositive men. J Adolesc Health. 1997;20:414–9. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin KL, Edlin BR, Faruque S, McCoy HV, Word C, Serrano Y, Inciardi J, Bowser B, Holmberg SD. Crack cocaine smokers who turn to drug injection: characteristics, factors associated with injection, and implications for HIV transmission. The Multicenter Crack Cocaine and HIV Infection Study Team. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;42:85–92. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Stoltz JA, Marshall BD, Lai C, Strathdee SA, Wood E. Childhood trauma and injection drug use among high-risk youth. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45:300–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.007. Epub 2009 May 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan HL, Wathen CN, Barlow J, Fergusson DM, Leventhal JM, Taussig HN. Interventions to prevent child maltreatment and associated impairment. Lancet. 2009;373:250–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61708-0. Epub 2008 Dec 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz SM, O'Cleirigh C, Hendriksen ES, Bullis JR, Stein M, Safren SA. Childhood sexual abuse and health risk behaviors in patients with HIV and a history of injection drug use. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:1554–60. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9857-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez TE, Gleghorn A, Marx R, Clements K, Boman M, Katz MH. Psychosocial histories, social environment, and HIV risk behaviors of injection and noninjection drug using homeless youths. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1998;30:1–10. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1998.10399665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CL, Strathdee SA, Kerr T, Li K, Wood E. Factors associated with early adolescent initiation into injection drug use: implications for intervention programs. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:462–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Buxton J, Rhodes T, Guillemi S, Hogg R, Montaner J, Wood E. Dose-response effect of incarceration events on nonadherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy among injection drug users. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1215–21. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar BE, Buka SL, Kessler RC. Child sexual abuse and subsequent psychopathology: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:753–60. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochnio JJ, Patrick D, Ho M, Talling DN, Dobson SR. Past infection with hepatitis A virus among Vancouver street youth, injection drug users and men who have sex with men: implications for vaccination programs. CMAJ. 2001;165:293–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ompad DC, Ikeda RM, Shah N, Fuller CM, Bailey S, Morse E, Kerndt P, Maslow C, Wu Y, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and age at initiation of injection drug use. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:703–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.019372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotzker RE, Metzger DS, Holmes WC. Childhood sexual and physical abuse histories, PTSD, depression, and HIV risk outcomes in women injection drug users: a potential mediating pathway. Am J Addict. 2007;16:431–8. doi: 10.1080/10550490701643161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Weissman MM, Wilber CH, Kleber HD. Pathways to opiate addiction: an evaluation of differing antecedents. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;141:437–46. doi: 10.1192/bjp.141.5.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy E, Boudreau JF, Boivin JF. Hepatitis C virus incidence among young street-involved IDUs in relation to injection experience. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;102:158–61. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy E, Haley N, Leclerc P, Boivin JF, Cedras L, Vincelette J. Risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection among street youths. CMAJ. 2001;165:557–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy E, Haley N, Leclerc P, Cedras L, Blais L, Boivin JF. Drug injection among street youths in Montreal: predictors of initiation. J Urban Health. 2003;80:92–105. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy E, Haley N, Leclerc P, Sochanski B, Boudreau JF, Boivin JF. Mortality in a cohort of street youth in Montreal. JAMA. 2004;292:569–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.5.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SG, Fuller CM, Shah N, Ompad DV, Vlahov D, Strathdee SA. Correlates of initiation of injection drug use among young drug users in Baltimore, Maryland: the need for early intervention. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2005;37:437–43. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2005.10399817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small W, Wood E, Betteridge G, Montaner J, Kerr T. The impact of incarceration upon adherence to HIV treatment among HIV-positive injection drug users: a qualitative study. AIDS Care. 2009;21:708–14. doi: 10.1080/09540120802511869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltz JA, Shannon K, Kerr T, Zhang R, Montaner JS, Wood E. Associations between childhood maltreatment and sex work in a cohort of drug-using youth. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65:1214–21. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomas JM, Vlahov D, Anthony JC. Association between intravenous drug use and early misbehavior. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1990;25:79–89. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(90)90145-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton G, Co SJ, Milloy MJ, Qi J, Kerr T, Wood E. High prevalence of childhood emotional, physical and sexual trauma among a Canadian cohort of HIV-seropositive illicit drug users. AIDS Care. 2011;23:714–21. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.525618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Marmorstein NR, White HR. Childhood victimization and illicit drug use in middle adulthood. Psychol Addict Behav. 2006;20:394–403. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.4.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Weiler BL, Cottler LB. Childhood victimization and drug abuse: a comparison of prospective and retrospective findings. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1999;67:867–80. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Stoltz JA, Montaner JSG, Kerr T. Evaluating methamphetamine use and risks of injection initiation among street youth: the ARYS study. Harm Reduction Journal. 2006;3:18. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Stoltz JA, Zhang R, Strathdee SA, Montaner JS, Kerr T. Circumstances of first crystal methamphetamine use and initiation of injection drug use among high-risk youth. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27:270–6. doi: 10.1080/09595230801914750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]