Abstract

Mast cells (MCs) are implicated in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). MC-specific chymase and tryptase play important roles in inducing endothelial cell expression of adhesion molecules and chemokines to promote leukocyte recruitment, degrading matrix proteins and activating protease-activated receptors to trigger smooth-muscle cell apoptosis, and activating other proteases to degrade medial elastin and to enhance angiogenesis. In experimental AAA, absence or pharmacological inhibition of chymase or tryptase reduced AAA formation and associated arterial pathologies, proving that these MC proteases participate directly in AAA formation. Increased levels of these proteases in human AAA lesions and in plasma from AAA patients suggest that these proteases are also essential to human AAA pathogenesis. Development of chymase or tryptase inhibitors or their antibodies may have therapeutic potential among affected human subjects.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is an inflammatory arterial disease that affects up to 9% of males over age 65. Lack of routine monitoring may jeopardize AAA patients, particularly those who have asymptomatic rupture-prone AAAs. Although endovascular surgical repair remains the only clinical treatment for human AAA, recent discoveries in the molecular and cellular mechanisms of AAA may lead to the development of novel preventive strategies and medications. The pathogenesis of AAA involves enhanced expression of endothelial adhesion molecules and chemokines, inflammatory cell adhesion and trans-subendothelium migration, aortic media inflammation and matrix protein destruction, smooth-muscle cell (SMC) loss and arterial wall thinning, lumenal endothelial cell (EC) death and desquamation, and ultimately aortic thrombus formation and rupture. Macrophages, T cells, and neutrophils are well-known inflammatory cells in human AAA lesions. Recent studies demonstrated that mast cells (MCs) are also present in human and experimental AAAs, and participate directly in experimental AAA (Sun et al. 2007b, Tsuruda et al. 2008, Mäyränpää et al. 2009).

In normal human aortas, very few MCs are located at the adventitia and intima (Mäyränpää et al. 2009). In human atherosclerotic lesions, abundant MCs are present in the intima, media, and adventitia (Jeziorska et al. 1997). In contrast, MCs increase mainly in the media and adventitia in human AAA lesions, together with T cells and macrophages, but are negligible in the intima (Mäyränpää et al. 2009). The numbers of total and degranulated (activated) MCs in the outer media and adventitia of human AAA are significantly higher than those in early and advanced human atherosclerotic lesions and normal aortas (Tsuruda et al. 2008). MC numbers in human AAA lesions correlate with maximal aortic diameters. AAA tissue extract preparation showed increased expression and activities of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9 (by gelatin zymography) and increased expression of MC-specific tryptase and stem cell factor (SCF) (Tsuruda et al. 2008). Although the exact molecule that drives MCs accumulation in human AAA lesions remains unknown, increased mRNA and protein levels of leukotriene C4 and its three key enzymes (5-lipoxygenase [5-LO], 5-LO-activating protein, and LTC4 synthase) were detected at the site of enriched inflammatory cells (Di Gennaro et al. 2010), suggesting that leukotriene participates in MC recruitment in human AAA. Several of our studies established a direct role of MC cytokines, chymase, and tryptase in AAA formation (Sun et al. 2007b, Sun et al. 2009, Zhang et al. 2011). In this brief review, we summarize our current understanding of how MC chymase and tryptase participate in the pathogenesis of AAA.

Role of mast cells in experimental AAA

The direct participation of MCs in AAA formation recently has been tested in several experimental animals. In both aortic elastase perfusion-induced and peri-aortic CaCl2 injury-induced AAA in mice, the absence of MCs in KitW-sh/W-sh mice protected against AAA formation. AAA lesion characterization demonstrated that MC deficiency significantly reduced media elastin degradation, media SMC loss, lesion macrophage and T-cell contents, adventitial angiogenesis, and lesion activities of cysteinyl cathepsins, MMP-2, and MMP-9. Reduced AAA formation, lesion macrophage contents, inflammatory cytokines (e.g., interferon-γ [IFN-γ]), and protease activities (cathepsins and MMPs) in KitW-sh/W-sh mice are fully or partially restored after mice received exogenous MCs from wild-type (WT) or tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α-deficient mice, but not those from interleukin (IL)-6-deficient or IFN-γ-deficient mice. Compared with AAA formation in WT mice, MC activation with compound 48/80 enlarged AAA sizes, increased lesion inflammation, protease expression, and elastin degradation, and reduced lesion MC number. In contrast, all these phenotypes were diminished or partially suppressed after mice received the MC stabilizer cromolyn (Sun et al. 2007b). In peri-aortic CaCl2 injury-induced AAA in rats, both total and activated MCs were increased in AAA lesions at 3, 7, and 14 days after injury. Absence of MCs in Ws/Ws rats or stabilization of MCs with tranilast (N-[3,4-dimethoxycinnamonyl]-anthranilic acid, a mast cell blocker) preserved elastin degradation, reduced MMP-2 and MMP-9 activities, and prevented AAA formation. Although aortic wall tissue macrophage numbers did not change, T-cell content and capillary density were significantly blunted. In angiotensin-II (Ang-II) infusion-induced AAA in apolipoprotein E-deficient (Apoe−/−) mice, tranilast also reduced AAA lesion area, lesion total and degranulated MC contents, T-cell content, capillary density, and MMP-9 expression and activity (Tsuruda et al. 2008). These observations from several experimental AAA models prove a direct participation of MCs in experimental AAA.

Interactions between mast cells and AAA-pertinent cells

SMCs, ECs, and inflammatory cells, such as macrophages and T cells, are major cell types in human AAA lesions. MCs interact with these cells and change their pathological functions. MCs, for example, use TNF-α to induce MMP-9 expression in macrophages and T cells (Baram et al. 2001, Tchougounova et al. 2005). Treatment of human macrophages with anti-TNF-α antibody suppresses MC-induced MMP-9 expression (Tsuruda et al. 2008). Conversely, MCs are rich in MMP-9, and T cells induce MC release of MMP-9 (Baram et al. 2001), another important protease in AAA formation.

MCs interact with SMCs and induce SMC apoptosis via either pro-inflammatory cytokines or proteases. MC-derived TNF-α binds to SMC surface death receptor, and initiates caspase-mediated apoptosis (Kovanen 2007). MCs also induce SMC apoptosis via the anoikis mechanism. MC-derived chymase triggers SMC apoptosis by inhibiting SMC collagen synthesis (Wang et al. 2001) or degrading SMC fibronectin and vitronectin, leading to SMC focal adhesion complex disruption (Leskinen et al. 2006, Heikkilä et al. 2008). MCs also release granzyme B to induce SMC apoptosis and EC disorganization (Pardo et al. 2007). We have shown that MCs release IL-6 and IFN-γ to induce SMC and EC cysteinyl cathepsin expression (Sun et al. 2007a), which may indirectly affect SMC or EC apoptosis (Stoka et al. 2007).

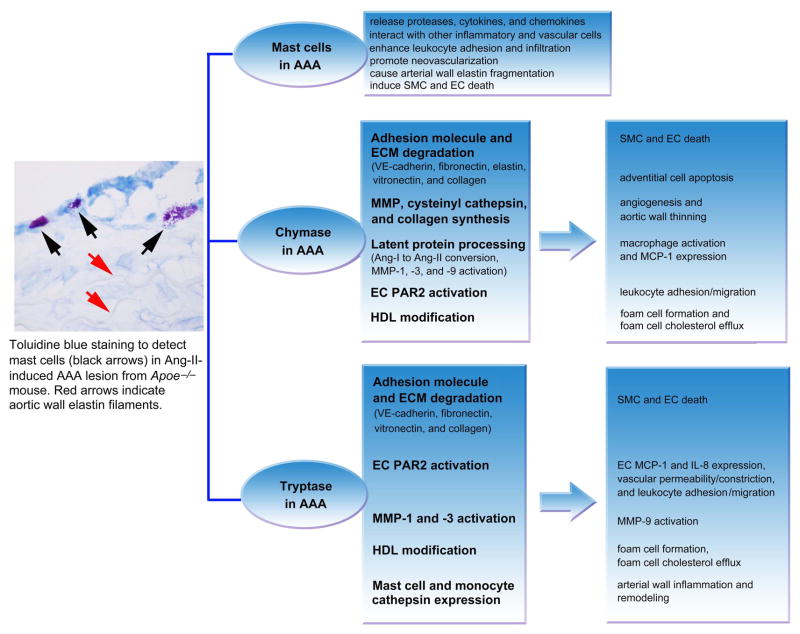

When MC releasate was added to rat or human ECs, it induced EC apoptosis by inactivating the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and Akt-dependent signaling pathways and activating caspase-8 and caspase-9 (Heikkilä et al. 2008). Chymase in the releasate degrades EC extracellular matrix protein vitronectin and fibronectin, providing additional mechanisms of MCs in inducing EC apoptosis. Antibodies against chymase or TNF-α improved EC survival (Heikkilä et al. 2008). Neovascularization is an important signature of human AAA — particularly prominent in thrombus-covered AAA or in thick aneurysmal wall — and correlates with medial MC density. Both MCs and neovascularization proportion in the media are significantly higher in human AAA lesions than in normal aortas. While human AAA tissue extracts have increased expression of proangiogenic factors (e.g., VE-cadherin, vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF], and its receptor, FLT1) and MC proteases (tryptase, chymase, and cathepsin G), AAA lumens contain CD42b+ platelet deposits and lack CD31+CD34+ ECs (Mäyränpää et al. 2009). Therefore, MC–EC interactions may promote angiogenesis in the microvessels, but may induce luminal EC death, endothelial erosion, and aortic rupture. Indeed, neovessels are more prevalent at the site of rupture in human AAA than in specimens from non-ruptured AAA (Choke et al. 2006). Essential roles of MCs in experimental AAA are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Role of mast cells, chymase, and tryptase in AAA. A representative AAA section from Apoe−/− mouse is shown to the left to indicate toluidine blue staining of mast cells in the adventitia. Direct roles of chymase and tryptase are shown in the middle two frames and consequent roles of chymase and tryptase are shown in the right two frames.

Mast cell protease functions related to AAA

Mast cell-specific neutral proteases include chymase, tryptase, and carboxypeptidase A (Pejler et al. 2010), and account for more than 25% of total cellular proteins (Schwartz et al. 1987, Pejler et al. 2010) —among which, tryptase is the predominant member and accounts for about 20% of total cellular proteins (Schwartz 1990), 3~50-fold greater mass than chymase (Schwartz et al. 1987). Chymase and tryptase are common antigens used to detect MCs. As in AAA lesions, chymase-positive and tryptase-positive MCs are next to von Willebrand factor-positive microvessels and correlate with each other in human atherosclerotic lesions (Kaartinen et al. 1996, Mäyränpää et al. 2006), suggesting a role of MC proteases in EC biology. Indeed, MCs induce EC death and chemokine expression. For example, treatment of fresh human coronary arteries intraluminally with recombinant human chymase or tryptase induced EC retraction, disruption, and desquamation, due to degradation of the EC adhesion molecules VE-cadherin, vitronectin, and fibronectin (Heikkilä et al. 2008, Mäyränpää et al. 2006). Although there is no study to detect MCs in the aortic wall from early AAA lesions, we have shown MC attachment in early human atherosclerotic lesions — i.e., fatty streaks (Xu and Shi 2012). Such attachment may induce EC chemokine expression, thereby recruiting other inflammatory cells, such as macrophages (Liu et al. 2009). When human umbilical cord ECs were treated with human leukemic MC granules for 24 hours, MC granules significantly increased EC expression of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) and IL-8 at protein and RNA levels. This MC granule activity can be blocked by anti-tryptase antibody, but not by chymase inhibitor SF-8257. Recombinant tryptase, but not recombinant chymase, also induces MCP-1 and IL-8 protein expression in ECs (Kinoshita et al. 2005). Tryptase-mediated chemoattractant molecule expression on ECs may also be mediated through protease-activated receptor (PAR) activation. Tryptase activates PAR-2 on ECs (Corvera et al. 1997), leading to increased vascular permeability, smooth muscle relaxation, systemic hypotension, bronchoconstriction, and leukocyte migration and infiltration (Vergnolle et al. 2001). As an alternative mechanism, tryptase activation of PAR-2 consequently activates membrane-associated iPLA2 (calcium-independent phospholipase A2) and enhances leukocyte adhesion to the EC monolayers (White and McHowat. 2007).

Tryptase and chymase share many proteolytic activities that are pertinent to AAA pathogenesis. Although MMP-9 activation in human AAA or in mice may depend on chymase (Tchougounova et al. 2005), chymase and tryptase both activate MMP-1 and MMP-3, which subsequently activate MMP-9 (Gruber et al. 1989, Saarinen et al. 1994). As in patients with coronary heart diseases, AAA patients have higher levels of serum low-density liproprotein (LDL) cholesterol, but lower levels of serum high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (Takagi et al. 2010). MC chymase and tryptase modify HDL by depleting preβ-HDL and other lipid-poor HDL particles, and reduce foam cell cholesterol efflux facilitated by ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) (Lee-Rueckert and Kovanen 2006). In human macrophages and possibly in SMCs, tryptase promotes intracellular lipid accumulation and foam-cell formation by reducing the expression of nuclear receptor LXRa (regulates lipid homeostasis), ABCA1, ABCG1 (involved in the cholesterol efflux pathway and macrophage foam-cell formation), and sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c) (regulates gene for de novo lipogenesis). Tryptase inhibitor APC366 can inhibit all of these activities (Yeong et al. 2010). These tryptase and chymase activities may explain why human AAA lesions also contain foam cells derived from macrophages and SMCs (Tanasković et al. 2010).

Chymase and tryptase also have their own unique activities. While chymase cleaves vitronectin and pro-collagen, tryptase degrades type IV collagen, although all of these contribute to diminished arterial wall structural integrity and enhanced propensity for AAA formation. Chymase, together with angiotensin-converting enzymes (ACEs), is essential in converting Ang-I into Ang-II (Miyazaki et al. 2006). We often consider Ang-II-forming activity as one of the readouts of chymase and ACE activities from AAA lesions. Indeed, both degranulated MC numbers and Ang-II-forming activities are higher in AAA lesions than in atherosclerotic lesions (Ihara et al. 1999). In addition to vasodilation activity, Ang-II also activates macrophages, leading to MCP-1 expression, which causes more monocyte/macrophage and neutrophil recruitment to the site of inflammation (Schieffer et al. 2000, Yusof et al. 2007).

Direct role of chymase and tryptase in AAA formation

MC accumulation in human AAA lesions has been confirmed using either chymase antibody-mediated or tryptase antibody-mediated immunohistological analysis. In a prospective clinical follow-up study of 103 Danish men, we found that plasma chymase levels correlated with AAA annual growth rate, but did not associate with initial AAA size (Sun et al. 2009). In a related Danish population-based randomized screening trial of 100 men with defined AAA and 35 age-matched male controls, plasma tryptase levels (after log transformation) were significantly higher in AAA patients than in controls, although many patients in the control group were smokers (42.9%) and had other cardiovascular complications, such as acute myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, stroke, or hypertension (total 25.7%). Initial AAA size and tryptase levels correlated weakly and insignificantly (P=0.106), but the mean annual AAA growth rate correlated significantly with plasma tryptase levels before (P=0.003) and after (P=0.005) adjustment for more than 10 potential AAA risk factors. Of note, Cox regression analysis demonstrated that high plasma tryptase levels in AAA patients increased the risk of later surgical repair before (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.74) and after (HR: 2.15) adjustment for AAA risk factors. Plasma tryptase levels also associated with overall mortality before (HR: 1.43) and after (HR: 3.17) adjustment (Zhang et al. 2011). These clinical observations suggest an important role of chymase and tryptase in human AAA.

The roles of chymase and tryptase in AAA have been tested in several experimental AAA models. In Ang-II infusion-induced AAA in Apoe−/− mice, oral administration of the chymase inhibitor NK3201 (30 mg/kg/day) significantly suppressed AAA lesion area, and reduced lesion MOMA-2+ monocyte/macrophage cells and MMP-9 expression and activity (Inoue et al. 2009). In elastase perfusion-induced AAA in dogs, while aortic diameter increased consistently at 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks post-perfusion, NK3201 (1 mg/kg/day) treatment prevented post-perfusion aortic diameter increase. NK3201 suppressed lumen area, aortic wall chymase levels, neutrophil contents, chymase and Ang-II forming activities, and MMP-9 activities (Furubayashi et al. 2007). In the same model in hamsters, NK3201 also attenuated AAA formation (Tsunemi et al. 2004). We recently proved a direct role of chymase in AAA. Using mice deficient in mouse MC protease-4 (MMCP-4; a human chymase ortholog) with aortic elastase perfusion-induced AAA, we demonstrated that MCs lacking chymase expression greatly reduced their ability to promote AAA formation. At 14 days post-perfusion, MMCP-4-deficient (Mcpt4−/−) mice were fully protected from AAA formation. At 8 weeks after elastase perfusion, Mcpt4−/− mice remained protected. Reduced AAA in Mcpt4−/− mice associated with reduced lesion adventitia cell apoptosis, media elastin degradation, and adventitia angiogenesis. All such improvements in Mcpt4−/− mice are partially reversed after mice receive adaptive transfer of MCs from WT mice, but not those from Mcpt4−/− mice (Sun et al. 2009). By unknown mechanisms, the absence of MMCP-4 reduced MMP and cysteinyl cathepsin expression in MCs, and reduced cathepsin activities in SMCs and the aortic wall. Reduced protease expression and activities may explain impaired media elastin degradation and adventitia angiogenesis. As discussed, chymase cleaves vitronectin (Heikkilä et al. 2008) and fibronectin (Leskinen et al. 2006), which may lead to SMC focal adhesion complex disruption. Chymase also inhibits SMC collagen synthesis (Wang et al. 2001). All these chymase activities contribute to SMC apoptosis, although we did not test whether matrix protein expression and deposition were altered in Mcpt4−/− mice. Unlike tryptase, chymase does not affect EC chemokine expression (Kinoshita et al. 2005), but it may still activate PAR-2 (Sharma et al. 2007). These activities may impair chymase-mediated leukocyte adhesion, migration, and accumulation in AAA lesions. Indeed, AAA lesion macrophage and T-cell contents in Mcpt4−/− mice were not always reduced at all three post-perfusion time points (Sun et al. 2009).

While chymase activity in AAA formation has been studied in several experimental AAA models using chymase inhibitor or chymase-deficient mice, tryptase inhibitors have not been tested in experimental AAA formation. Our recent study using mouse MC protease-6 (MMCP-6)–deficient (Mcpt6−/−) mice, however, proved that tryptase participates directly in AAA. In elastase perfusion-induced AAA, while aortic diameters increased over time at 7, 14, and 56 days post-perfusion in WT mice, those in Mcpt6−/− mice remained unchanged. Lesion macrophage and T-cell contents and major histocompatibility complex class-II (MHC-II) molecule expression were also significantly reduced in Mcpt6−/− mice (Zhang et al. 2011). Reduced AAA formation and lesion inflammation in Mcpt6−/− mice were largely reversed after mice receiving exogenously administered MCs obtained from WT mice, but not those from Mcpt6−/− mice, confirming a role of MC tryptase in experimental AAA. As discussed, tryptase induces EC expression of chemokines IL-8 and MCP-1 (Kinoshita et al. 2005). AAA lesions from Mcpt6−/− mice had significantly reduced MCP-1 expression at both 14 days and 56 days post-perfusion. ECs from Mcpt6−/− mice also had significantly reduced expression of (cytokines) TNF-α and IL-6 and of (chemokines) KC (an IL-8 homolog), MIP-2 (macrophage inflammatory protein-2), and LIX (lipopolysaccharide-induced CXC), which may all contribute to reduced leukocyte accumulation in AAA lesions in Mcpt6−/− mice — although we do not know whether PAR-2 activation was also impaired in AAA lesions from Mcpt6−/− mice. Furthermore, monocytes from Mcpt6−/− mice showed reduced migration in response to chemoattractant challenge. ECs and monocytes do not express tryptase, and we therefore do not have an explanation for these observations. Other mechanisms may exist.

Tryptase activates MMP-1 and MMP-3, which indirectly affect MMP-9 activities (Gruber et al. 1989, Saarinen et al. 1994), but absence of MMCP-6 only affected cathepsin expression and activities in monocytes and MCs, and did not affect MMP, cathepsin G, or chymase (Zhang et al. 2011). Tryptase mediates collagen-IV proteolysis (Iddamalgoda et al. 2008), which may affect SMC survival. In cultured mouse aortic SMCs, MCs induced SMC apoptosis, but those from Mcpt6−/− mice showed greatly reduced induction of SMC apoptosis (Zhang et al. 2011). Consistent with these observations, AAA lesion media SMC apoptosis was also reduced in Mcpt6−/− mice, compared with those from WT mice, but tryptase deficiency did not affect adventitia cell apoptosis (Zhang et al. 2011). While chymase deficiency reduced AAA lesion angiogenesis or in vitro microvessel growth, absence of tryptase did not affect angiogenesis in AAA lesions. Tryptase therefore may not play a major role in MC-induced angiogenesis (Sun et al. 2007b, Mäyränpää et al. 2009). Figure 1 summarizes the roles of both chymase and tryptase in experimental AAA.

Summary and future perspective

Both chymase and tryptase are increased in human and experimental AAA lesions, and in blood from AAA patients. Although more mechanisms may still be revealed, available evidence suggests that these proteases contribute to leukocyte adhesion and migration, EC and SMC apoptosis, expression and activation of MMP and cathepsins, and foam-cell formation. MC protease regulation of MMP and cysteinyl cathepsin expression and activation, which have been proven essential in human and experimental AAA and atherosclerosis (Keeling et al. 2005, Cheng et al. 2011, Cheng et al. 2012), suggests that chymase and tryptase indirectly influence AAA formation. Direct evidence of chymase and tryptase participation in AAA came from experimental AAA using mice deficient in MMCP-4 and MMCP-6. These lines of studies suggest the potential of using chymase and tryptase inhibitors or antibodies in human AAA medication. Although not tested in humans, positive data in several experimental AAA experiments with chymase inhibitor NK3201 strongly support this possibility. We believe that tryptase inhibitor will have similar inhibitory activity in experimental AAA, and possibly in human AAA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baram D, Vaday GG, Salamon P, Drucker I, Hershkoviz R, Mekori YA. Human mast cells release metalloproteinase-9 on contact with activated T cells: juxtacrine regulation by TNF-alpha. J Immunol. 2001;167:4008–4016. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.4008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng XW, Huang Z, Kuzuya M, Okumura K, Murohara T. Cysteine protease cathepsins in atherosclerosis-based vascular disease and its complications. Hypertension. 2011;58:978–986. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.180935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng XW, Shi GP, Kuzuya M, Sasaki T, Okumura K, Murohara T. Role for cysteine protease cathepsins in heart disease: focus on biology and mechanisms with clinical implication. Circulation. 2012;125:1551–1562. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.066712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choke E, Thompson MM, Dawson J, et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture is associated with increased medial neovascularization and overexpression of proangiogenic cytokines. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2077–2082. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000234944.22509.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corvera CU, Déry O, McConalogue K, et al. Mast cell tryptase regulates rat colonic myocytes through proteinase-activated receptor 2. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1383–1393. doi: 10.1172/JCI119658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Gennaro A, Wågsäter D, Mäyränpää MI, et al. Increased expression of leukotriene C4 synthase and predominant formation of cysteinyl-leukotrienes in human abdominal aortic aneurysm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:21093–21097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015166107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furubayashi K, Takai S, Jin D, et al. The significance of chymase in the progression of abdominal aortic aneurysms in dogs. Hypertens Res. 2007;30:349–357. doi: 10.1291/hypres.30.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber BL, Marchese MJ, Suzuki K, et al. Synovial procollagenase activation by human mast cell tryptase dependence upon matrix metalloproteinase 3 activation. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1657–1662. doi: 10.1172/JCI114344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkilä HM, Lätti S, Leskinen MJ, Hakala JK, Kovanen PT, Lindstedt KA. Activated mast cells induce endothelial cell apoptosis by a combined action of chymase and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:309–314. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.151340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iddamalgoda A, Le QT, Ito K, Tanaka K, Kojima H, Kido H. Mast cell tryptase and photoaging. possible involvement in the degradation of extra cellular matrix and basement membrane proteins. Arch Dermatol Res. 2008;300(Suppl 1):S69–S76. doi: 10.1007/s00403-007-0806-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihara M, Urata H, Kinoshita A, et al. Increased chymase-dependent angiotensin II formation in human atherosclerotic aorta. Hypertension. 1999;33:1399–1405. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.6.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue N, Muramatsu M, Jin D, et al. Effects of chymase inhibitor on angiotensin II-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm development in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204:359–364. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeziorska M, McCollum C, Woolley DE. Mast cell distribution, activation, and phenotype in atherosclerotic lesions of human carotid arteries. J Pathol. 1997;182:115–122. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199705)182:1<115::AID-PATH806>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaartinen M, Penttilä A, Kovanen PT. Mast cells accompany microvessels in human coronary atheromas. implications for intimal neovascularization and hemorrhage. Atherosclerosis. 1996;123:123–131. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(95)05794-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeling WB, Armstrong PA, Stone PA, Bandyk DF, Shames ML. An overview of matrix metalloproteinases in the pathogenesis and treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2005;39:457–464. doi: 10.1177/153857440503900601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita M, Okada M, Hara M, Furukawa Y, Matsumori A. Mast cell tryptase in mast cell granules enhances MCP-1 and interleukin-8 production in human endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1858–1863. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000174797.71708.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovanen PT. Mast cells. multipotent local effector cells in atherothrombosis. Immunol Rev. 2007;217:105–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee-Rueckert M, Kovanen PT. Mast cell proteases. physiological tools to study functional significance of high density lipoproteins in the initiation of reverse cholesterol transport. Atherosclerosis. 2006;189:8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leskinen MJ, Heikkilä HM, Speer MY, et al. Mast cell chymase induces smooth muscle cell apoptosis by disrupting NF-kappaB-mediated survival signaling. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:1289–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Divoux A, Sun J, et al. Genetic deficiency and pharmacological stabilization of mast cells reduce diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Nat Med. 2009;15:940–945. doi: 10.1038/nm.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäyränpää MI, Heikkilä HM, Lindstedt KA, Walls AF, Kovanen PT. Desquamation of human coronary artery endothelium by human mast cell proteases. implications for plaque erosion. Coron Artery Dis. 2006;17:611–621. doi: 10.1097/01.mca.0000224420.67304.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäyränpää MI, Trosien JA, Fontaine V, et al. Mast cells associate with neovessels in the media and adventitia of abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:388–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki M, Takai S, Jin D, Muramatsu M. Pathological roles of angiotensin II produced by mast cell chymase and the effects of chymase inhibition in animal models. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;112:668–676. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo J, Wallich R, Ebnet K, et al. Granzyme B is expressed in mouse mast cells in vivo and in vitro and causes delayed cell death independent of perforin. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1768–1779. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pejler G, Rönnberg E, Waern I, Wernersson S. Mast cell proteases. multifaceted regulators of inflammatory disease. Blood. 2010;115:4981–4990. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-257287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saarinen J, Kalkkinen N, Welgus HG, Kovanen PT. Activation of human interstitial procollagenase through direct cleavage of the Leu83-Thr84 bond by mast cell chymase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:18134–18140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieffer B, Schieffer E, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, et al. Expression of angiotensin II and interleukin 6 in human coronary atherosclerotic plaques. potential implications for inflammation and plaque instability. Circulation. 2000;101:1372–1378. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.12.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz LB. Tryptase from human mast cells. biochemistry, biology and clinical utility. Monogr Allergy. 1990;27:90–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz LB, Irani AM, Roller K, Castells MC, Schechter NM. Quantitation of histamine, tryptase, and chymase in dispersed human T and TC mast cells. J Immunol. 1987;138:2611–2615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R, Prasad V, McCarthy ET, et al. Chymase increases glomerular albumin permeability via protease-activated receptor-2. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;297:161–169. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9342-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoka V, Turk V, Turk B. Lysosomal cysteine cathepsins. signaling pathways in apoptosis. Biol Chem. 2007;388:555–560. doi: 10.1515/BC.2007.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Sukhova GK, Wolters PJ, et al. Mast cells promote atherosclerosis by releasing proinflammatory cytokines. Nat Med. 2007a;13:719–724. doi: 10.1038/nm1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Sukhova GK, Yang M, et al. Mast cells modulate the pathogenesis of elastase-induced abdominal aortic aneurysms in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007b;117:3359–3368. doi: 10.1172/JCI31311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Zhang J, Lindholt JS, et al. Critical role of mast cell chymase in mouse abdominal aortic aneurysm formation. Circulation. 120:973–982. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.849679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi H, Manabe H, Kawai N, Goto SN, Umemoto T. Serum high-density and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol is associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm presence. a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Angiol. 2010;29:371–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanasković I, Mladenović-Mihailović A, Usaj-Knezević S, et al. Histochemical and immunohistochemical analysis of ruptured atherosclerotic abdominal aortic aneurysm wall. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2010;67:959–964. doi: 10.2298/vsp1012959t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchougounova E, Lundequist A, Fajardo I, Winberg JO, Abrink M, Pejler G. A key role for mast cell chymase in the activation of pro-matrix metalloprotease-9 and pro-matrix metalloprotease-2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9291–9296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410396200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunemi K, Takai S, Nishimoto M, et al. A specific chymase inhibitor, 2-(5-formylamino-6-oxo-2-phenyl-1,6-dihydropyrimidine-1-yl)-N-[[3,4-dioxo-1-phenyl-7-(2-pyridyloxy)]-2-heptyl]acetamide (NK3201), suppresses development of abdominal aortic aneurysm in hamsters. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:879–883. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.063974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuruda T, Kato J, Hatakeyama K, et al. Adventitial mast cells contribute to pathogenesis in the progression of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Circ Res. 2008;102:1368–1377. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.173682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergnolle N, Wallace JL, Bunnett NW, Hollenberg MD. Protease-activated receptors in inflammation, neuronal signaling and pain. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:146–152. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01634-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Shiota N, Leskinen MJ, Lindstedt KA, Kovanen PT. Mast cell chymase inhibits smooth muscle cell growth and collagen expression in vitro. transforming growth factor-beta1-dependent and -independent effects. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1928–1933. doi: 10.1161/hq1201.100227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White MC, McHowat J. Protease activation of calcium-independent phospholipase A2 leads to neutrophil recruitment to coronary artery endothelial cells. Thromb Res. 2007;120:597–605. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu JM, Shi GP. Emerging role of mast cells and macrophages in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Endocr Rev. 2012;33:71–108. doi: 10.1210/er.2011-0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeong P, Ning Y, Xu Y, Li X, Yin L. Tryptase promotes human monocyte-derived macrophage foam cell formation by suppressing LXRalpha activation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:567–576. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusof M, Kamada K, Gaskin FS, Korthuis RJ. Angiotensin II mediates postischemic leukocyte-endothelial interactions. role of calcitonin gene-related peptide. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H3032–H3037. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01210.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Sun J, Lindholt JS, et al. Mast cell tryptase deficiency attenuates mouse abdominal aortic aneurysm formation. Circ Res. 2011;108:1316–1327. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]