Hu et al. explore whether silencing by promoter DNA methylation plays a role in cell fate choice during early nervous system and neural crest development. In chick embryo studies, the authors show that the neural specifier genes Sox2 and Sox3 are direct targets of DNA methyltransferase3A. They conclude that DNA methylation acts as a molecular switch that turns off neural tube transcription factors and so facilitates neural crest gene expression in the developing neural tube.

Keywords: DNMT3A, neural tube, neural crest, Sox2, Sox3

Abstract

Here, we explore whether silencing via promoter DNA methylation plays a role in neural versus neural crest cell lineage decisions. We show that DNA methyltransferase3A (DNMT3A) promotes neural crest specification by directly mediating repression of neural genes like Sox2 and Sox3. DNMT3A is expressed in the neural plate border, and its knockdown causes ectopic Sox2 and Sox3 expression at the expense of neural crest markers. In vivo chromatin immunoprecipitation of neural folds demonstrates that DNMT3A specifically associates with CpG islands in the Sox2 and Sox3 promoter regions, resulting in their repression by methylation. Thus, DNMT3A functions as a molecular switch, repressing neural to favor neural crest cell fate.

During development, neural crest stem cells contribute to many uniquely vertebrate derivatives, including peripheral ganglia and the craniofacial skeleton (Le Douarin 1982). Although neural crest precursors initially reside within the neural tube, they subsequently segregate from other neuroepithelial cells by a heretofore unknown mechanism. Whereas the remainder of the neural tube will form the CNS, neural crest cells undergo an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), emigrate from the CNS, and migrate into the periphery (Sauka-Spengler and Bronner-Fraser 2008). Single-cell lineage analysis has shown that individual cells within the dorsal neural tube can contribute to both the CNS and neural crest (Bronner-Fraser and Fraser 1988), suggesting that premigratory dorsal neural tube cells are not yet committed to a neural crest fate. Subsequently, a subpopulation of dorsal neural tube cells produces bona fide neural crest cells that migrate extensively to populate diverse derivatives, ranging from peripheral neurons to craniofacial cartilage and melanocytes. The molecular mechanisms underlying the neural tube-to-neural crest transition are a long-standing mystery. In this study, we explored the possibility that silencing via promoter DNA methylation plays a role in this cell fate choice during embryonic development.

De novo DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) recognize CpG islands and newly methylate DNA by catalyzing the transfer of a methyl group to cytosine residues (Cheng and Blumenthal 2008). In cancer and stem cells, when such CpG island methylation occurs in the promoter region, gene expression is inhibited (Momparler and Bovenzi 2000; Miranda and Jones 2007; Altun et al. 2010). The de novo DNMTs DNMT3A (Jurkowska et al. 2011) and DNMT3B are vital for normal mammalian development and have been implicated in disease (Linhart et al. 2007; Ehrlich et al. 2008; Yan et al. 2011). For example, DNMT3A−/− mice die several weeks after birth, and DNMT3B−/− embryos have rostral neural tube defects and growth impairment (Okano et al. 1999). Moreover, mutations in human DNMT3B result in immunodeficiency centromeric instability facial anomalies syndrome, in which patients exhibit craniofacial abnormalities (Jin et al. 2008), suggesting a defect in neural crest development. In contrast, the function of DNMT3A in early development is not understood. Here, we show that DNMT3A plays a critical function in de novo methylation during early nervous system and neural crest development.

Results and Discussion

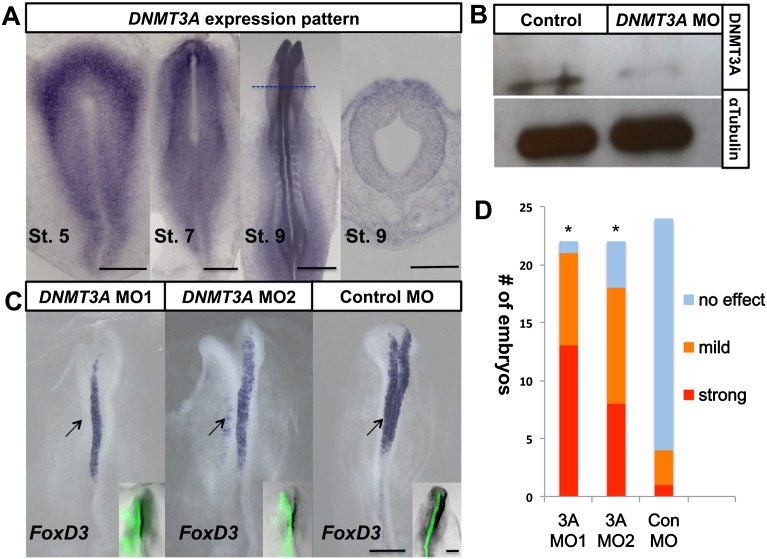

Expression pattern of DNMT3A in the early chick embryo

As a first step in analyzing its possible function, we examined the expression pattern of DNMT3A transcripts by in situ hybridization. Intriguingly, DNMT3A is highly expressed at the neural plate border at gastrula stages, contrasting with low levels in the neural plate (Fig. 1A, St. 5–7). Subsequently, transcripts are confined to the neural folds containing premigratory neural crest precursors (Fig. 1A, St. 9) and, later, in migrating neural crest cells, labeled with HNK-1 antibody (Supplemental Fig. S1A). Thus, at early developmental stages, DNMT3A is selectively expressed in tissues associated with neural crest and early neural tube development.

Figure 1.

DNMT3A is expressed at sites of neural crest formation, and its loss of function blocks expression of the neural crest specifier gene FoxD3. (A) Expression pattern of DNMT3A in stage 5–9 chick embryo by in situ hybridization. DNMT3A is strongly expressed in the neural plate border (St. 5–7) and dorsal neural tube (St. 9). Bars: whole mount, 500 μm; section, 100 μm. (B) Western blot of dorsal neural tubes (five pooled embryos) shows that DNMT3A protein level was reduced on the electroporated side compared with the control side; α-tubulin levels were unchanged. (C) Two morpholinos against DNMT3A (MO1 and MO2; FITC in inset) caused reduction of FoxD3 expression at stage 8 after electroporation (shown at left; arrow) compared with the contralateral internal control side or control morpholino-electroporated embryos. Bar, 200 μm. (D) Quantitation of numbers of DNMT3A MO-treated and control MO-treated embryos with either strong or mild loss of FoxD3 expression of MO versus the control side of same embryo. The asterisk indicates significant differences (P < 0.01) by contingency table followed by χ2 test. See also Supplemental Figure S1.

Knockdown of DNMT3A blocks neural crest specification, as assayed by FoxD3 expression, in a cell-autonomous manner

To test the functional consequences of loss of DNMT3A during neural crest specification, we designed two different fluorescein-tagged translation-blocking antisense morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) targeted against DNMT3A. These were electroporated into one-half of the early chick embryo at gastrulation stages 4/5, with the uninjected side serving as an internal control (Basch et al. 2006). To verify that the knockdown was effective, we performed Western blots comparing the protein levels in the electroporated side versus the control half of the same embryo and found that a band corresponding to DNMT3A protein was significantly decreased in the presence of DNMT3A MOs (Fig. 1B). We examined the effects of loss of DNMT3A on expression of FoxD3, as it is one of the earliest neural crest markers to appear in the dorsal neural tube. FoxD3 was dramatically down-regulated after loss of DNMT3A on the morpholino-electroporated side of the embryo (Fig. 1C,D) in an apparently dose-dependent fashion, as the severity of the phenotype increased with the amount of morpholino introduced (Supplemental Fig. S1B).

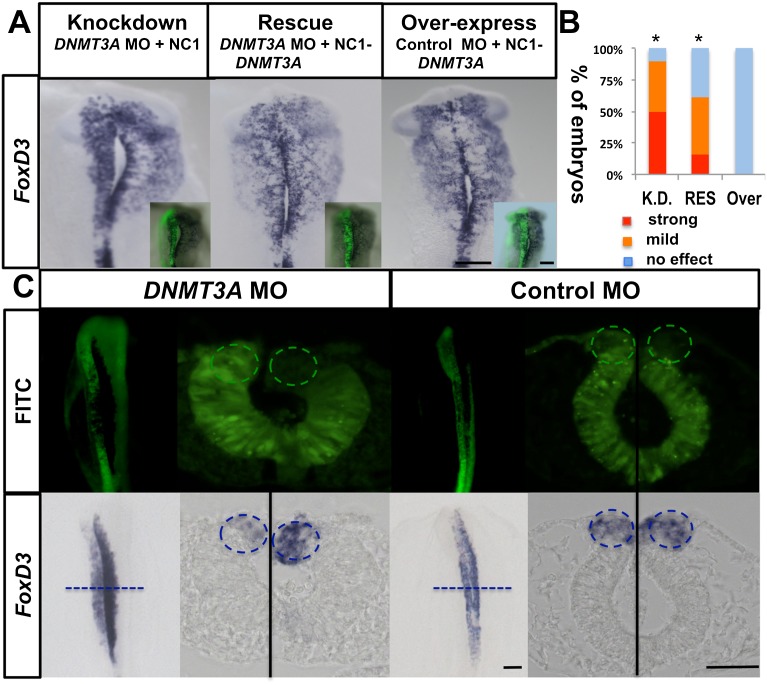

To control for the specificity of action of the DNMT3A morpholino and demonstrate that the observed phenotype was not due to off-target binding, we coelectroporated the DNMT3A MO with a construct encoding exogenous DNMT3A under the control of a cranial FoxD3 enhancer, NC1, which turns on at early stage 8. This enhancer drives exogenous DNMT3A only in premigratory cranial neural crest cells. Despite the fact that the morpholino was introduced much earlier, this resulted in marked rescue of the loss-of-function phenotype, restoring FoxD3 expression (Fig. 2A,B). To examine whether the catalytic activity of DNMT3A was important for its function, we coelectroporated the DNMT3A morpholino and a rescue construct in which the catalytic domains of DNMT3A were removed. Under coelectroporation conditions identical to those above, this mutated form of DNMT3A failed to rescue the loss-of-function phenotype (Supplemental Fig. S2A,B). This demonstrates that catalytic activity is critical for DNMT3A function during neural crest development.

Figure 2.

Loss of FoxD3 is rescued by exogenous DNMT3A in a neural crest cell-autonomous manner. (A) Expression of DNMT3A protein in premigratory neural crest rescues the loss of the FoxD3 phenotype: Each embryo was electroporated on the left side with either the DNMT3A MO or control MO (green in inset) in combination with either a DNMT3A rescue construct (NC1-DNMT3A) or empty vector (NC1 alone). The rescue construct contains the coding region of DNMT3A under the control of a cranial neural crest-specific enhancer for FoxD3 plus HSV-tk basal promoter. At stage 10, the loss of neural crest marker FoxD3 was largely rescued by NC1-DNMT3A plus the DNMT3A MO. Overexpression of the DNMT3A rescue construct alone did not alter FoxD3 expression. Bar, 500 μm. (B) Quantitation of the percentage of DNMT3A knockdown (K.D.), rescue (RES), and overexpression (Over) embryos in A with either strong or mild loss of FoxD3 expression. P < 0.01 by contingency table followed by χ2 test. Knockdown, n = 10; rescue, n = 13; overexpression, n = 5. (C) Effect of DNMT3A loss of function is cell-autonomous to the neural crest-forming region: The DNMT3A MO or control MO was electroporated throughout the neural tube on the left side and into the neural tube with the exception of the dorsal neural folds (circled) on the right side. Loss of FoxD3 only occurred when the dorsal neural fold was electroporated with the DNMT3A MO, as evident in the transverse section. DNMT3A MO, n = 8/8; control MO n = 12/12. P < 0.01 by contingency table followed by χ2 test. Bar, 100 μm. See also Supplemental Figure S2.

Although we hypothesize that DNMT3A acts in a cell-autonomous fashion in the presumptive neural crest cells, it is possible that aberrant interactions between neural crest precursors and more ventral neural tube cells result in a neural crest phenotype. DNMT3A is expressed at high levels at the neural plate border, neural folds, and premigratory neural crest but is also expressed in the neural tube, albeit at much lower levels. To test whether the function of DNMT3A is cell-autonomous, we compared its effect on the neural crest versus the rest of the neural tube. Because we cannot selectively target the neural crest region in a predictable fashion, we electroporated the morpholino into the entire neural tube on one side of each embryo and into the neural tube with the exception of the dorsal neural fold region on the opposite side. In 100% of cases, we noted that down-regulation of FoxD3 only occurred when DNTM3A protein was down-regulated in the presumptive neural crest itself (Fig. 2C). The finding that FoxD3 is absent from cells containing the DNMT3A MO but present in cells lacking the DNMT3A MO in the dorsal neural fold region definitively demonstrates that DNMT3A acts cell-autonomously (Supplemental Fig. S2D).

Multiplex analysis reveals that loss of DNMT3A up-regulates neural genes while down-regulating neural crest specifier genes

In order to understand global and multiplexed changes in gene expression caused by DNMT3A knockdown, we performed NanoString analysis to monitor and quantify 73 transcripts, including genes expressed in the neural crest, neural tube, neural plate, neural plate border, placodes, and nonneural ectoderm and those involved in cell proliferation and cell death. Each DNMT3A knockdown embryo was analyzed at late stage 8, by comparing the morpholino-electroporated side with the uninjected side of the same embryo. Because DNMTs are thought to inhibit transcription by methylating the promoter region of target genes, we were particularly interested in genes that were up-regulated as a consequence of down-regulating DNMT3A, as these represent potential direct targets. Interestingly, the results show that transcriptional regulators characteristic of neural fate specification—Sox2 and Sox3 as well as the neural plate border gene Zic1 and some EMT and placode-related genes—were up-regulated after DNMT3A knockdown (Fig. 3A; Supplemental Fig. S3A–C).

Figure 3.

Sox2, Sox3, and Zic1 are potential downstream targets of DNMT3A, as identified using multiplex NanoString analysis and verified by in situ hybridization. (A) NanoString analysis reveals genes up-regulated (above diagonal lines) and down-regulated (below diagonal lines) by DNMT3A knockdown. The injected side of DNMT3A MO-treated embryos shows >25% up-regulation of neural tube genes Sox2, Sox3, and Zic1 (n = 3), and there was >25% reduction of neural crest specifier genes Snail2, Sox9, TNIP1, FoxD3, Sox8, and Sox10 (see also Supplemental Fig. S3). No differences were noted in control morpholino-treated embryos (n = 3) (Supplemental Fig. S3). The blue line represents 25% variation between the injected and uninjected sides. (B) Transverse sections of stage 8 embryos electroporated with the DNMT3A MO (FITC; inset) confirm that Sox2, Sox3, and Zic1 expression was expanded into the neural crest territory (blue circle) when compared with the internal control side (n = 12 of 12). Bars: whole mount, 200 μm; section, 100 μm. (C) Transverse section of stage 8 embryos electroporated with the DNMT3A MO (green) confirms that Sox2 (red) protein expression was expanded into the neural crest territory (red circle) when compared with the internal control side, while FoxD3 (blue) protein expression was missing in the neural crest territory (blue circle). n = 7 of 8. Control morpholino-treated embryos show equivalent Sox2 and FoxD3 expression on both sides (Supplemental Fig. S3). Bar, 100 μm.

Sox2 (Pevny and Lovell-Badge 1997; Graham et al. 2003) was of particular interest, since its misexpression in the neural folds blocks expression of the neural crest gene Snail2 (Wakamatsu et al. 2004). Furthermore, Sox2 is a well-known pluripotency gene and is one of the four genes necessary to reprogram somatic cells into pluripotent stem cells (Pawlak and Jaenisch 2011). Therefore, we used in situ hybridization to verify the up-regulation of Sox2 noted by NanoString analysis. The results show that loss of DNMT3A causes expansion of Sox2 into the neural crest territory, whereas on the control side of the same embryo, Sox2 is absent from the neural crest domain (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, this is accompanied by changes in morphology of the dorsal neural tube, which appears less broad and more neuroepithelial than the control side. In contrast to Sox2, the pluripotency genes Nanog and Oct4/PouV exhibited little or no expression in the cranial neural tube (Canon et al. 2006; N Hu and ME Bronner, unpubl.). Moreover, their expression was unchanged after DNMT3A knockdown (data not shown).

Sox2 and Sox3 are paralogs with overlapping function. Therefore, we examined the effects of DNMT3A knockdown on Sox3 expression and found that, like Sox2, it is up-regulated in the dorsal neural tube after morpholino knockdown (Fig. 3B). Thus, both genes are affected similarly, although Sox2 comes on earlier than Sox3 and appears to be the dominant neural specifier. Like Sox2 and Sox3, Zic1 also was up-regulated in the dorsal neural tube after loss of DNMT3A (Fig. 3B).

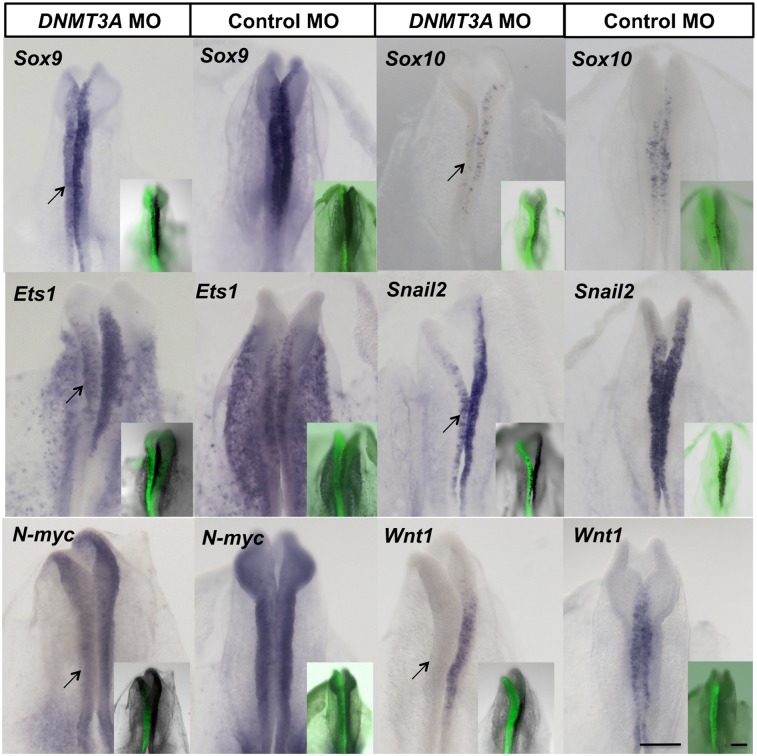

Concomitant with up-regulation of Sox2, neural crest specification markers were down-regulated in DNMT3A knockdown embryos, as shown in our NanoString data (Fig. 3A). This was verified by in situ hybridization for other neural crest specifiers and dorsal neural tube genes, including Sox9, Sox10, Snail2, Ets1, Wnt1, and N-Myc. Like FoxD3, all of these appeared to be down-regulated upon loss of DNMT3A (Fig. 4). Given that Wnt signaling has been implicated in neural crest specification and Wnt1 was down-regulated after DNMT3A knockdown, we tested whether activated β-catenin could rescue the DNMT3A morpholino phenotype. However, the results show no change in FoxD3 expression (Supplemental Fig. S4A,B).

Figure 4.

Neural crest specifier and dorsal neural tube genes are down-regulated after knockdown of DNMT3A. The DNMT3A MO or control MO was electroporated into the left side of the embryo (FITC, shown in insets), and the subsequent effects on expression patterns of neural crest and dorsal neural tube genes were examined by whole-mount in situ hybridization. Sox9, Sox10, Ets1, Snail2, N-myc, and Wnt1 are down-regulated (arrow) upon introduction of the DNMT3A MO when compared with the internal control side or control morpholino-electroporated embryos. Bar, 200 μm.

Coimmunostaining of Sox2 and FoxD3 in a single embryo treated with the DNMT3A MO further demonstrates that loss of DNMT3A up-regulates neural genes such as Sox2 while down-regulating neural crest specifier genes such as FoxD3 (Fig. 3C; Supplemental Fig. S3E). We noted no significant change in cell death, as shown by Casp-3 staining (Supplemental Fig. S4C). In addition, there was no change in the expression of neural plate border genes like Msx1 and BMP4 in the dorsal neural tube (Supplemental Fig. S4D).

To demonstrate a direct link between Sox2 up-regulation and the reduction of neural crest gene expression, we electroporated a construct containing avian Sox2 (Wakamatsu et al. 2004) into the stage 4–5 neural plate, resulting in overexpression throughout the neural tube, including ectopic expression in the dorsal region. Consistent with our findings after DNMT3A knockdown, this caused down-regulation of the neural crest specifier genes FoxD3, Sox10, and Snail2 (Supplemental Fig. S5). For the reciprocal experiment, we examined whether morpholino knockdown of Sox2 and/or Sox3 was sufficient to induce neural crest cell fate in the neural tube. Loss of Sox2, Sox3, or both in combination failed to convert neural tube to neural crest cells. However, these factors are critical for normal neural induction, and their loss, as expected, led to severe neural defects.

Neural specifier genes Sox2 and Sox3 are direct targets of DNMT3A

The NanoString and in situ data raise the intriguing possibility that de novo methylation of the Sox2 promoter region by DNMT3A may be essential for repression of the Sox2 in the dorsal neural folds and necessary for the switch in its identity from neural to neural crest. To test this in the in vivo context, we used chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) followed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) to assess whether Sox2 is a direct target of DNMT3A. To this end, dorsal neural folds were dissected from stage 8 embryos and processed for microChIP as previously described (Betancur et al. 2010; Strobl-Mazzulla et al. 2010). The data show that DNMT3A associates with the Sox2 promoter region but not with the N2 enhancer region of Sox2 (Fig. 5; Uchikawa et al. 2003). Similar to Sox2, ChIP analysis shows that DNMT3A also occupies the promoter region of Sox3, the paralog of Sox2 (Fig. 5). In contrast, Zic1, which was also up-regulated after DNMT3A knockdown, does not appear to be a direct target of DNMT3A, since ChIP analysis failed to show binding at its promoter region (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Sox2 and Sox3 are direct targets of DNMT3A. ChIP was used to detect binding of DNMT3A in the vicinity of the transcriptional start site (TSS) of Sox2 and Sox3. The Y-axis represents input percentage (ChIP enriched/input), and the X-axis represents the distance from the TSS in kilobases. (A) The results show high occupancy of DNMT3A at 0.5 kb from the TSS of Sox2 at stage 8. DNMT3A significantly binds to Sox2 at 0.5 kb (0.0044% input) compared with the negative control region ncN2 (0.0008% input) or IgG binding at 0.5 kb (0.0013% input). Graph shows mean value ± standard deviation (SD) of a representative experiment. (B) The results show high occupancy of DNMT3A at −0.5 kb and 0.5 kb from the TSS of Sox3 at stage 8. DNMT3A significantly binds to Sox3 at −0.5 kb (0.0102% input) and 0.5 kb (0.0069% input) compared with the negative control region ncN2 (0.0023% input) or IgG binding at −0.5 kb (0.0049% input) and 0.5 kb (0.0011% input). Graph shows mean value ± standard deviation (SD) of a representative experiment. (C) Schematic diagram summarizing the effects of DNMT3A knockdown. In wild-type (control side), DNMT3A (purple) directly represses Sox2/3 in the dorsal neural tube, thus facilitating expression of neural crest specifier genes like Snail2, FoxD3, and Sox10. After DNMT3A knockdown, Sox2/3 expression expands into the dorsal neural tube region, resulting in down-regulation of FoxD3, Snail2, Sox10, and other neural crest specifiers and thus conferring a neural tube rather than neural crest fate.

We further examined the methylation pattern of Sox2 and Sox3 in the dorsal neural tube at stage 8. As expected, the results show that both Sox2 and Sox3 are methylated in the vicinity of their promoters (Supplemental Fig. S2C). Taken together, these findings definitively show that DNMT3A directly binds to the promoter regions of Sox genes and represses their transcription via methylation, thus allowing the acquisition of neural crest gene expression.

Our data show that DNA methylation act as a molecular switch to turn off neural tube transcription factors, thus facilitating neural crest gene expression and fate acquisition. Previous studies on the molecular mechanisms of DNMT3A function have been focused on hematopoietic and neural stem cells and glioma cells in tissue culture. These studies using in vitro data show that DNMT3A can promote cell differentiation by repressing pluripotency genes (Trowbridge and Orkin 2011). Consistent with this, our results in the developing embryo demonstrate that DNMT3A promotes neural crest cell type specification in an in vivo context by repressing neural genes like Sox2 and Sox3. Although the mechanism by which DNMT3A is recruited to the promoter region of target genes is unknown, it has been shown to interact with numerous factors on transcription factor arrays (Hervouet et al. 2009). Although these have yet to be validated, particularly in vivo, this list includes some neural plate border and neural crest specifier genes like Msx1, tfAP2α, Id2, and Myc. Thus, it is intriguing to speculate that DNMT3A may be recruited to the Sox2 promoter by some of these factors that are selectively expressed in the neural crest-forming domain.

In some cases, de novo methyltransferases can also mediate methylation-independent gene repression by colocalizing with heterochromatin and associating with HP1 and MeCBP (methyl-CpG-binding protein). For example, in zebrafish neurogenesis, DNMT3B cooperates with histone methyltransferase G9a to inhibit expression of Lef1 (Rai et al. 2010). Thus, it is particularly interesting that, in the neural folds, DNMT3A acts via regulation of the promoter region rather than the enhancer region, as demonstrated by our ChIP data. This shows that, in addition to cis-regulatory events, epigenetic influences are a critical mechanism for regulating transcription. Our discovery that DNA methylation promotes neural crest specification at the expense of neural tube identity provides important insights into the mechanisms that determine whether a cell becomes part of the CNS or peripheral nervous system.

Materials and methods

Embryos

Fertilized chicken eggs were incubated at 37°C to the desired stages.

In situ hybridization

Embryos were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed with PBS/0.1% Tween, dehydrated in MeOH, and stored at −20°C. Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed as described (Wilkinson 1992; Acloque et al. 2008). Dioxigenin-labeled RNA probes were made from DNA plasmids or ESTs of DNMT3A, Sox2, Sox9, Sox10, Snail2, FoxD3, Wnt1, Ets1, Nmyc, Msx1, and Bmp4. Embryos were sectioned at 16–18 μm.

Electroporation

Embryos were electroporated at stage 4–5 as described (Sauka-Spengler and Barembaum 2008) using DNMT3AMO1 (over ATG codon) (TGGGTGTGTCACTGCTTTCCACCAT) and/or DNMT3AMO2 (95 nucleotides upstream of ATG) (CAGTGTCCCCACGGCGCTTCCTGCT). The rescue construct included the coding region of DNMT3A (NM001024832.1) under the control of NC1 or empty NC1 as control. For each embryo, 0.6 mM MO + 0.5 μg/μL DNA was used for knockdown experiments, and 0.4 mM MO + 1.5 μg/μL DNA was used for rescue experiments. The MO was targeted to the presumptive neural crest region with five 50-msec pulses of 5.2 V at 100-msec intervals. Electroporated embryos were maintained in culture dishes with 1 mL of albumen and then fixed.

NanoString nCounter

Half-dorsal neural folds of DNMT3A MO-treated embryos were dissected in lysis buffer (Ambion RNAqueous-Micro Isolation kit). RNA lysates were hybridized to the probe set, incubated overnight at 65°C, washed, eluted according to the nCounter Prep Station manual, and counted by nCounter Digital Analyzer.

ChIP

Dorsal neural tubes from 25 stage eight embryos were dissected and extracted (three experiments per condition). Cells were cross-linked and sonicated to yield 300- to 800-base-pair fragments. Samples were evenly split for DNMT3A antibody (Abcam), control rabbit anti-IgG (Abcam), and Input. Antibodies were preincubated with Protein A magnetic beads (Invitrogen) before incubation with a sonicated protein–DNA complex. Samples were washed, eluted, and reverse cross-linked. Final DNA pull-down was purified and served as a template for qPCR of the Sox2 promoter region. Three replicates were loaded for each sample, and the results were quantified using the DDCt method. Analysis was done using Applied Biosystems' instructions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. M. Simoes-Costa and M. Barembaum for helpful discussions. We are grateful to Dr. Yoshio Wakamatsu for kindly providing the Sox2 overexpression construct. This work was supported by F31DE021643 and 5 T32 GM07616 to N.H., and HD037105 and DE16459 to M.E.B.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.198747.112.

References

- Acloque H, Wilkinson DG, Nieto MA 2008. In situ hybridization analysis of chick embryos in whole-mount and tissue sections. Methods Cell Biol 87: 169–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altun G, Loring JF, Laurent LC 2010. DNA methylation in embryonic stem cells. J Cell Biochem 109: 1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basch ML, Bronner-Fraser M, Garcia-Castro MI 2006. Specification of the neural crest occurs during gastrulation and requires Pax7. Nature 441: 218–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancur P, Bronner-Fraser M, Sauka-Spengler T 2010. Genomic code for Sox10 activation reveals a key regulatory enhancer for cranial neural crest. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 3570–3575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronner-Fraser M, Fraser S 1988. Cell lineage analysis shows multipotentiality of some avian neural crest cells. Nature 335: 161–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canon S, Herranz C, Manzanares M 2006. Germ cell restricted expression of chick Nanog. Dev Dyn 235: 2889–2894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X, Blumenthal RM 2008. Mammalian DNA methyltransferases: A structural perspective. Cell Press Structure 16: 341–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich M, Sanchez C, Shao C, Nishiyama R, Kehrl J, Kuick R, Kubota T, Hanash SM 2008. ICF, an immunodeficiency syndrome: DNA methyltransferase 3B involvement, chromosome anomalies, and gene dysregulation. Autoimmunity 41: 253–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham V, Khudyakov PE, Pevny L 2003. Sox2 functions to maintain neural progenitor identity. Neuron 39: 749–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervouet E, Vallette FM, Cartron PF 2009. Dnmt3/transcription factor interactions as crucial players in targeted DNA methylation. Epigenetics 4: 487–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin B, Tao Q, Peng J, Soo HM, Wu W, Ying J, Fields CR, Delmas AL, Liu X, Qiu J, et al. 2008. DNA methyltransferase 3B (DNMT3B) mutations in ICF syndrome lead to altered epigenetic modifications and aberrant expression of genes regulating development, neurogenesis and immune function. Hum Mol Genet 17: 690–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkowska RZ, Jurkowski TP, Jeltsch A 2011. Structure and function of mammalian DNA methyltransferases. ChemBioChem 12: 206–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin N. 1982 The neural crest. Cambridge University Press. New York. [Google Scholar]

- Linhart HG, Lin H, Yamada Y, Moran E, Steine EJ, Gokhale S, Lo G, Cantu E, Ehrich M, He T, et al. 2007. Dnmt3b promotes tumorigenesis in vivo by gene-specific de novo methylation and transcriptional silencing. Genes Dev 21: 3110–3122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda TB, Jones PA 2007. DNA methylation: The nuts and bolts of repression. J Cell Physiol 213: 384–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momparler RL, Bovenzi V 2000. DNA methylation and cancer. J Cell Physiol 183: 145–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano M, Bell DW, Haber DA, Li E 1999. DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are essential for de novo methylation and mammalian development. Cell 99: 247–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak M, Jaenisch R 2011. De novo DNA methylation by Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b is dispensable for nuclear reprogramming of somatic cells to a pluripotent state. Genes Dev 25: 1035–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pevny L, Lovell-Badge R 1997. Sox genes find their feet. Curr Opin Genet Dev 7: 338–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai K, Jafri IF, Chidester S, James SR, Karpf AR, Cairns BR, Jones DA 2010. Dnmt3 and G9a cooperate for tissue-specific development in zebrafish. J Biol Chem 285: 4110–4121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauka-Spengler T, Barembaum M 2008. Gain- and loss-of-function approaches in the chick embryo. Methods Cell Biol 87: 237–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauka-Spengler T, Bronner-Fraser M 2008. A gene regulatory network orchestrates neural crest formation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 557–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobl-Mazzulla P, Sauka-Spengler T, Bronner-Fraser M 2010. Histone demethylase JmjD2A regulates neural crest specification. Dev Cell 19: 460–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trowbridge JJ, Orkin SH 2011. Dnmt3a silences hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal. Nat Genet 44: 13–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchikawa M, Ishida Y, Takemoto T, Kamachi Y, Kondoh H 2003. Functional analysis of chicken Sox2 enhancers highlights an array of diverse regulatory elements that are conserved in mammals. Dev Cell 4: 509–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakamatsu Y, Endo Y, Osumi O, Weston JA 2004. Multiple roles of SOX2, an HMG-box transcription factor in avian neural crest development. Dev Dyn 229: 74–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson DG. 1992 Whole mount in situ hybridization of vertebrate embryos. In situ hybridization: A practical approach (ed. D.G. Wilkinson), pp. 75–83. IRL Press, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Yan XJ, Xu J, Gu ZH, Pan CM, Lu G, Shen Y, Shi JY, Zhu YM, Tang L, Zhang XW, et al. 2011. Exome sequencing identifies somatic mutations of DNA methyltransferase gene DNMT3A in acute monocytic leukemia. Nat Genet 43: 309–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]