Abstract

Purpose

Hot flashes (HFs) are a particularly common and distressing symptom in breast cancer survivors (BCS). Given its low rate of side effects, acupuncture shows promise as a therapeutic approach for HFs but little is known about BCS’s decision-making about use of acupuncture. This study seeks to identify attitudes and beliefs about using acupuncture for HFs by BCS.

Methods

Using the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) as a conceptual framework, we conducted semi-structured interviews among women with stage I–III breast cancer who had finished primary treatment and were currently experiencing HFs. Interviews were taped, transcribed, and coded. We used a modified grounded theory approach to analyze the data.

Results

Twenty-five BCS (13 Caucasian/12 African American) participated in the study. Respondents stated that their intended use of acupuncture for HFs would be dependent on: 1) Expected therapeutic effects (e.g. pain relief, energy); 2) Practical concerns (e.g. fear of needles, practitioner experience, time commitment); and 3) Source of decision support/validation (e.g. family members, physicians, self). Although constructs in the TPB accounted for many decision factors, respondents identified two major themes outside of the TPB: 1) Viewing acupuncture as a natural alternative to medications, and 2) Assessing the degree of HFs as bothersome enough in the context of other medical co-morbidities to trigger the need for therapy.

Conclusion

BCS expressed varied expected therapeutic benefits, practical concerns, and decision support, emphasizing the “natural appeal” and symptom appraisal as key determinants in using acupuncture for HFs. Incorporating these factors in counseling BCS may promote patient-centered communication leading to improved hot flash management and quality of life.

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer survivors (BCS), 2.5 million in number, constitute the largest group of cancer survivors in the U.S.1 Hot flashes (HFs) are a common and disruptive clinical problem affecting nearly two-thirds of all breast cancer survivors (BCS).2–4 Many cancer therapies such as oophorectomy, chemotherapy, and endocrine therapies may produce a rapid and drastic estrogen withdrawal that can lead to onset or worsening of HFs. Compared to women without breast cancer, BCS experience HFs of greater frequency, severity, and duration.3 Previous studies have shown that HFs are also correlated with insomnia, fatigue, reduced libido, and poor quality of life in BCS.3, 5–7 Following treatments, as many BCS return to their primary care physicians (PCPs),8 management of HFs is a common issue faced by both parties.1

Treatment of HFs in BCS has proven difficult due to the limitations and side effects of conventional therapies. Estrogen replacement, the most effective treatment for HFs,9 has been found to cause new cancer events in BCS10 and is now generally avoided.9 Safer non-estrogen therapies have recently emerged, including clonidine,11 megestrol acetate,12–14 gabapentin,15, 16 and several SSRI/SNRIs.17–20 However, the effectiveness of these treatments has been moderate at best, and many of the therapies can have unpleasant toxicities such as insomnia, weight gain, or sexual side effects.21 Further, a recent study found that paroxetine may decrease the efficacy of tamoxifen and increase breast cancer mortality.22 As a result, some women are reluctant to take medications to control their HFs and seek non-pharmacologic interventions.23, 24

Breast cancer survivors are known to use complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) extensively.25–27 Preliminary studies suggest that acupuncture may reduce HFs in BCS with fewer side effects than conventional pharmacologic therapies.28, 29 Use of acupuncture has been shown to reduce hot flashes in BCS by greater than 50%, both during the day and at night.29 Acupuncture is associated with improved sleep quality in postmenopausal women,30 and has been shown to continue to reduce HFs as long as 6 months after treatment.31 Despite promising early results, evidence of acupuncture’s therapeutic effects remains inconclusive, given the non-equivocal benefit compared against sham controls and study design limitations.32, 33 Like decision making for cancer treatment, BCS often have a difficult time making decisions to manage HFs when several options exist and evidence is not clear as to the best option. In this setting, an understanding of individual patient attitudes and preferences are particularly important to help inform patient-centered decision making. Thus, we conducted this qualitative study to identify the specific attitudes, beliefs, and barriers held by BCS about making decisions to use acupuncture for hot flashes and general beliefs about acupuncture. We also explored how these beliefs differ for Caucasians and African Americans.

METHODS

We conducted open-ended, semi-structured interviews with women with stage I–III breast cancer who had finished primary cancer treatments (surgery, chemotherapy, radiation) and were currently experiencing daily HFs. Participants were recruited from an outpatient breast cancer oncology clinic in an urban academic hospital. Purposeful sampling was used to ensure the sample was diverse in race, age, and hot flash severity. Specifically, we created a table to help guide enrollment so there were approximately equal numbers of subjects enrolled in the categories of Caucasian/African American and perceived hot flash severity (mild/moderate, severe/very severe). As we analyzed the transcripts of already enrolled subjects, we then aimed at enriching specific demographics (e.g. women younger than 50) to capture a greater variation in the sample. Regulatory approval was obtained through the University of Pennsylvania’s Instituional Review Board as well as the Abramson Cancer Center’s Clinical Trials Scientific Review and Monitoring Committee.

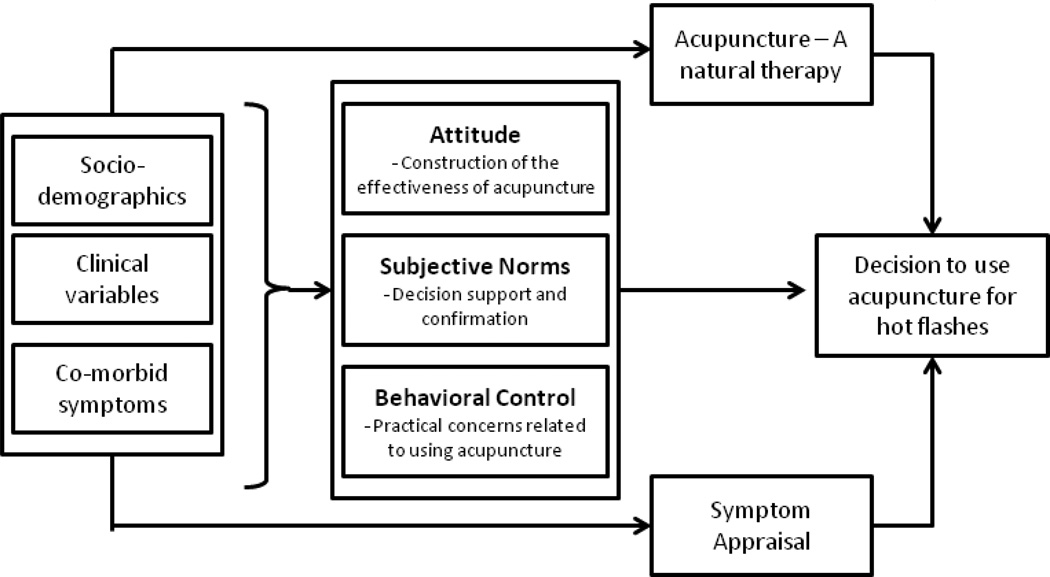

The interview guide was developed using the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)34 as a conceptual framework. The TPB model contains three domains: attitude toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control that contribute to one’s behavioral intention.34 This model has been used in numerous research settings to understand the decisions about specific health behaviors such as mammogram use35, 36 and also in the context of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) research.37, 38 The interview questions were pilot tested and revised for clarity. Interviewers were all trained and supervised in semi-structured interviewing techniques by the study medical anthropologist (Barg). Each interview lasted approximately one hour and was recorded and then transcribed by a professional transcription company. Participants also completed self-reported surveys to collect general socio-demographic and health information.

De-identified transcripts were imported into QSR NVivo 8.0 (QSR International Pty Ltd, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia) to manage the data. A coding scheme and coding dictionary were developed by the research team based on a close reading of the transcripts. Team members coded 5 transcripts together in order to improve the reliability of coding and to standardize code definitions. Research assistants coded the remainder of the transcripts. Coding consistency was determined using a feature built into the software for this purpose. Transcripts and codes were discussed weekly in team meetings. We achieved saturation on all major themes after 25 interviews.

RESULTS

The study participants included 13 Caucasian (52%) and 12 African American women (48%). The median age for participants was 57 years (range: 38–79 years). Fifteen (60%) study participants had a college degree or greater, while 10 (40%) reported less than college. Eleven (44%) women reported entering menopause naturally, while therapy-induced menopause (defined as menopause being brought on by either surgical or medical processes) was identified in 13 (52%) women. Among the participants, 15 (60%) had used some form of CAM in the past 12 months, while 10 (40%) had not. Furthermore, only four participants had used acupuncture in the past for symptoms unrelated to hot flashes. Each participant’s characteristics can be seen in Table 1. We identified three themes related to decisions to use acupuncture among BCS that fit into the main constructs of the TPB: 1) Construction of the effectiveness of acupuncture (Attitude); 2) Practical concerns related to using acupuncture (Perceived behavioral control); 3) Decision support and confirmation (Subjective norms). However, two themes directly relate to patients’ final decisions to use acupuncture were beyond the constructs in the TBP. They were: 4) Viewing acupuncture as a natural alternative to medicine; and 5) Symptom appraisal in the context of other medical co-morbidities.

Table 1.

Specific Characteristics of Subjects

| Subject | Age | Race* | Education** | Reason for Menopause | Current General Health Status |

Severity of HF, Daily |

CAM*** Use |

Prior Acupuncture Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 58 | Caucasian | Grad/Prof | Natural | Fair | Very Severe | Yes | Yes |

| B | 46 | Caucasian | College | Peri-menopausal | Very Good | Very Severe | Yes | No |

| C | 62 | Caucasian | College | Natural | Very Good | Severe | Yes | Yes |

| D | 53 | Caucasian | Grad/Prof | Chemotherapy | Very Good | Moderate | No | No |

| E | 65 | Caucasian | College | Natural | Good | Severe | Yes | No |

| F | 62 | Caucasian | College | Natural | Good | Severe | Yes | Yes |

| G | 38 | Caucasian | College | Surgical | Very Good | Severe | Yes | No |

| H | 79 | AA | High School | Surgical | Good | Severe | No | No |

| I | 62 | Caucasian | Grad/Prof | Natural | Good | Moderate | Yes | No |

| J | 53 | Caucasian | Grad/Prof | Chemotherapy | Very Good | Very Severe | Yes | Yes |

| K | 69 | AA | College | Natural | Good | Mild | No | No |

| L | 73 | AA | High School | Natural | Good | Mild | Yes | No |

| M | 42 | Caucasian | Grad/Prof | Chemotherapy | Very Good | Mild | Yes | No |

| N | 49 | Caucasian | College | Chemotherapy | Very Good | Mild | No | No |

| O | 73 | AA | High School | Surgical | Fair | Severe | No | No |

| P | 48 | AA | Grad/Prof | Chemotherapy | Very Good | Severe | Yes | No |

| Q | 59 | AA | Grad/Prof | Surgical | Good | Moderate | No | No |

| R | 51 | AA | College | Natural | Very Good | Moderate | No | No |

| S | 56 | AA | College | Natural | Fair | Very Severe | Yes | No |

| T | 45 | Caucasian | Grad/Prof | Chemotherapy | Good | Moderate | Yes | No |

| U | 54 | AA | College | Chemotherapy | Excellent | Mild | Yes | No |

| V | 60 | AA | High School | Surgical | Fair | Mild | Yes | No |

| W | 57 | Caucasian | Grad/Prof | Natural | Excellent | Moderate | No | No |

| X | 67 | AA | College | Natural | Good | Mild | No | No |

| Y | 48 | AA | Grad/Prof | Surgical | Good | Mild | No | No |

Race: AA=African American

Education: Grad/Prof=Graduate or Professional

CAM: Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Construction of the effectiveness of acupuncture

Most participants had a modest general understanding of acupuncture and no one had any specific prior knowledge of acupuncture’s effectiveness for hot flashes. However, many individuals built varying levels of expected benefits of acupuncture upon their personal experiences or those of their family members/friends, mostly related to using acupuncture to treat pain. Some drew from the exposure to mass media such as television and the internet. They generalized what they learned about acupuncture for specific conditions (e.g. back pain) to a much broader perceived benefit of acupuncture. Several African American women relied on acupuncture’s long history and wide use in China as evidence that the therapy has been tested by time and therefore must have some benefit for them. African American women were also more likely to state that they had little exposure to acupuncture themselves or via family members than Caucasian women. Two Caucasian women with greater education specified the need for evidence generated from clinical trials targeted at hot flashes to aid their decision for using acupuncture for hot flashes (see Table 2a).

Table 2.

Constructs from the Theory of Planned Behavior

| a: Construction of Effectiveness (Perceived benefits) | ||

| My friend who had acupuncture for a frozen shoulder is a breast cancer survivor, and so if I was gonna do acupuncture I would talk to her about her experience, which was very positive, you know, for her because physical therapy didn’t improve her range of motion but acupuncture did. | ||

| Subject P: 48yrs, African American, Graduate/Professional education | ||

| I remember the movie that I saw where the guy, I can’t remember what his name was, who was dying of cancer, went to a Chinese acupuncturist to try to get him to relax and to do some inner thoughts. | ||

| Subject Q: 59yrs, African American, High School education | ||

| I know that when I was very depressed one time, when my relationship of many, many years ended and I was really severely depressed I went to a place in New York and I went in an acupuncture program with a Dr. [redacted] up there and it helped. | ||

| Subject B: 46yrs, Caucasian, College education | ||

| Just what my husband tells me and that it helps reconfigurate the flow sometimes of pain or different things. He has a lot of pain so and it helps with his back pain and shoulder pain. And he’s had five hip replacements so he uses it for that. And he said it’s also relaxing for him…I know it helps, acupuncture helps. | ||

| Subject E: 65yrs, Caucasian, College education | ||

| My grandmother had crippling rheumatoid arthritis and in the 1970s, late seventies, she used to drag herself into Chinatown in New York City to have acupuncture…And she got tremendous relief from it. And that was my first personal… she was the first person I knew who ever used acupuncture. And for everything I hear and read and see it’s very effective for a lot of things. | ||

| Subject I: 62yrs, Caucasian, Graduate/Professional education | ||

| I don’t know how it would work, but it’s been working for the Chinese, I guess it would work for me. | ||

| Subject S: 56yrs, African American, College education | ||

| If I guess maybe if there was an ongoing study that was maybe yielding a lot of positive results, you know, and then maybe I would consider it. | ||

| Subject G: 38yrs, Caucasian, College education | ||

| b: Practical concerns related to using acupuncture (Perceived behavior controls) | ||

| I would be concerned about the person who was doing the sterility, the cleanliness, their experience doing it. | ||

| Subject I: 62yrs, Caucasian, Graduate/Professional education | ||

| I always wondered whether it was going to hurt. I just couldn’t believe that needles sticking out of your forehead, but I don’t know. | ||

| Subject Q: 59yrs, African American, Graduate/Professional education | ||

| I guess I am just thinking back because I do have issues with lymphedema, so slight because I manage it. I get very, very concerned and paranoid when people come on my left side because it is like I am very guarded. That is the area that you stay away from. | ||

| Subject U: 54 yrs, African American, College education | ||

| I’m a pretty lazy person. So if I can just be at home and pop a pill in my mouth rather than have to go somewhere and have acupuncture. | ||

| Subject D: 53yrs, Caucasian, College education | ||

| I think the one issue with acupuncture as far as I understand it is that having to get the treatment, I guess, on a certain schedule, whether it be once a week or twice a week, and having to sort of persist with that. | ||

| Subject P: 48yrs, African American, Graduate/Professional education | ||

| c: Decision Support and Confirmation (Social norm) | ||

| I would go to my doctor, but when it came to the decision on me doing the acupuncture, the decision was mine alone. | ||

| Subject X: 67yrs, African American, College education | ||

| I may ask my husband or my three children, but the final decision is mine. | ||

| Subject E: 65yrs, Caucasian, College education | ||

| I would ask my primary care physician. I would ask a person who does acupuncture. And I would ask a family member who’s a doctor. | ||

| Subject C: 62yrs, Caucasian, College education | ||

| I would probably go to my sister and she probably would research something and tell me whether to agree with them or not. | ||

| Subject D: 53yrs, Caucasian, Graduate/Professional education | ||

| I do rely very heavily on Dr… He’s my internist that I’ve had for over twenty years. | ||

| Subject E: 65yrs, Caucasian, College education | ||

| My primary care doctor’s the one I go through with just about any and everything that I have to have done. | ||

| Subject O: 73yrs, African American, High School education | ||

Practical concerns related to using acupuncture

Some respondents stated that they would never want acupuncture because of their fear of needles. A few respondents wondered how acupuncture may affect their lymphedema (i.e. Will needling make their lymphedema worse?) or other medical conditions. Two women stated that pills are easy to take therefore are a more desired choice in comparison to acupuncture. A number of women also listed finding a credible practitioner, location of practice proximal to their residence, and the time commitment to the therapy as potential barriers to using acupuncture (see Table 2b).

Decision support and confirmation

The majority of the participants indicated that the decision to choose a treatment modality for hot flashes is entirely theirs. Participants often cited two groups of individuals they turn to when they make decisions about medical care in general: 1) Family members (spouse, partner, or adult children); and 2) Physicians. Interestingly, while some breast cancer survivors, especially Caucasian survivors, turn to their oncologists for issues related to symptom management, African Americans see their PCP as their main resource with the information to assist their decision making about treating hot flashes (see Table 2c).

Viewing acupuncture as a natural alternative to medicine

When we asked why individuals may choose acupuncture for managing hot flashes, most responses were actually centered not so much on what acupuncture is, but rather what acupuncture is not, specifically, not a medication. This was true for all African American and most Caucasian respondents. Many of the women described medications as “toxic,” “foreign,” and having other side effects that may be worse than the hot flashes themselves. At the same time, they endorsed using a treatment that is natural even when effectiveness is uncertain. Several African American women stated that they were already taking many medications for a variety of other conditions and they would not consider adding another pill to manage hot flashes as a viable option; thus, they prefer a natural alternative. African American women used particularly emotional descriptors (“I hate pills”) when discussing their aversion to another medicine (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Viewing acupuncture as a natural alternative to medicine

| I’d rather have acupuncture instead of medication because it something that I don’t have to put in my body. |

| Subject V: 60yrs, African American, High School education |

| I hate taking pills. I have enough of ‘em to take as it is. |

| Subject K: 69yrs, African American, College education |

| Because I think as a cancer person, who has had cancer and has been treated with very invasive means, surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, you don’t want another foreign object in your body. |

| Subject T: 45yrs, Caucasian, Graduate/Professional education |

| I’m not a person that likes to take meds. So, I would think there would be a little bit more natural for you. |

| Subject S: 56yrs, African American, College education |

| …Because I’m taking enough medicine now…I take six pills…seven, eight, nine, ten pills a day…you, that’s just too many pills. |

| Subject O: 73yrs, African American, High School education |

Symptom appraisal in the context of other medical co-morbidities

Another main theme that emerged relates directly to whether an individual perceived her hot flashes as bothersome enough to initiate treatment of any kind. Women spoke specifically about evaluating whether their hot flashes were severe or bothersome enough to warrant another intervention in the context of their other medical conditions. While some individuals cited their HFs as tolerable, several African American women with severe HFs, considered treating other symptoms (e.g. back pain) as more important and needing more urgent treatment by acupuncture than their hot flashes (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Symptom appraisal in the context of other medical co-morbidities

| If he [the oncologist] told me “Well it [acupuncture] will help with your hot flashes…” I mean my hot flashes aren’t gonna kill me. You know what I mean…I’m not gonna subject myself to acupuncture because it will help with my hot flashes. If he told me that it was a guarantee that I would never again have cancer, then sign me up, you know. I would be the first one out the door. |

| Subject G: 38yrs, Caucasian, College education |

| The only thing that I really have a problem with is I have back problems and that’s about the only thing I would wanna, you know, use it [acupuncture] for if I was gonna use it for anything. |

| Subject K: 69yrs, African American, College education |

| I would like there to be a study on migraines and acupuncture. That is my main problem right now. |

| Subject N: 49yrs, Caucasian, College education |

| I would still be going for acupuncture for hot flashes except I don’t have the time and they’re not so intense that I want to take the time off from work to do it. |

| Subject J: 53yrs, Caucasian, Graduate/Professional education |

| So if the hot flashes are bad but they don’t completely stop my life and they don’t completely keep me in bed and all that, I might just wing it and not participate in anything. |

| Subject C: 62yrs, Caucasian, College education |

| I’m at my life end almost, you know what I’m saying? So I really don’t need something like this [acupuncture] that would help the younger girls, women that are married and have husbands and things and going through all of these things. If that acupuncture help ‘em, help ‘em. See with me right now, I don’t… It’s not gonna help me. It may help me but it wouldn’t be that I have to keep up with my husband or my children. My children are almost as old as I am and my husband’s gone so I mean I don’t have anybody to really have to worry about. |

| Subject H: 79yrs, African American, High School education |

DISCUSSION

Hot flashes are a bothersome symptom affecting hundreds of thousands of breast cancer survivors. In this study, we identified attitudes/beliefs, aspects of perceived behavioral control, and social norms related to the intention of using acupuncture for hot flashes. As expected from the TPB, we found that patients constructed therapeutic benefit and practical concerns in the setting of limited knowledge about acupuncture. While they rely on family and physicians for treatment information and decision support; survivors often ‘own’ the final decision. Beyond constructs in the TPB, we found that a desire for natural alternatives to medication was the main driver for survivors’ intentions to use acupuncture. The primary reason survivors would not want acupuncture for hot flashes was an appraisal that their hot flashes were not bothersome or urgent enough to be treated when they were experiencing other co-morbid conditions.

Several previous qualitative studies of factors affecting general use of CAM (rather than acupuncture specifically) among BCS39–42 have reported similar themes, such as that survivors believe that CAM therapies have minimal side effects39, 41, 42 and can be safely used to complement conventional therapies.39–42 Our study specifically found that one of the major determinants of acupuncture use among BCS was its appeal as a natural alternative. Studies also suggest that CAM is often used for managing symptoms related to cancer and its treatments and for boosting the immune system.39, 41, 42 Our study focused on hot flashes, a prevalent and bothersome symptom experienced by BCS, and revealed symptom appraisal of the severity of hot flashes to be one of the primary reasons for acupuncture use among BCS. However, to our knowledge, no qualitative studies have focused specifically on understanding the use of a single CAM modality among BCS to alleviate hot flashes. Furthermore, our study included BCS from both Caucasian and African American groups, as well as different educational backgrounds and prior CAM experience. Our approach overcomes some of the sampling limitations of previous research, such as including only CAM users,39 mostly Caucasians with higher socio-economic levels,42 or only Chinese participants.40

Given the fairly modest understanding of acupuncture and a lack of specific knowledge of acupuncture for hot flashes, an individual often relies on her family and consults her physician about the use of acupuncture for hot flashes. Compared with Caucasian women, African Americans tend to turn to their PCPs for information and decision support for symptom management. This is consistent with a previous study that found African Americans were more likely to endorse the delivery of survivorship care by PCPs.8 Our study underlines the importance for PCPs to be knowledgeable about acupuncture as well as therapeutic options for managing hot flashes in the context of survivorship so they can be well-equipped to facilitate decision making by their patients.

Although the TPB has been used to explain intentions to use CAM,37, 38 we were interested to find that it did not account for all of the factors that women described as affecting their intentions to use acupuncture. The TPB, like much of traditional health behavior theory, is based on the underlying notion of rational thought in which patients are assumed to be highly motivated to maintain or return to a universally agreed upon definition of good health.43, 44 Rational health decisions are based on maximizing benefits and minimizing losses or costs.45 For example, the TPB posits that if a woman has a positive attitude about acupuncture (attitude), has no significant barriers to obtaining acupuncture (perceived behavioral control), and has important others in her social network who advocate for using modalities such as acupuncture (subjective norms), she will likely intend to use acupuncture for symptoms such as HFs. Despite this, we found that symptom appraisal and desire for a natural remedy were important determinants as well, even though they did not fit into the TPB model. Many interventions operate under a similar premise that women will use a utilitarian model for making decisions about treating breast cancer symptoms. It is tempting to use traditional help-seeking models in research and practice because they explain much middle-class health-seeking behavior. However, these approaches treat as external to the model personal, cultural, and social factors which contribute to the meaning and experience of cancer related symptoms. We have modified the original constructs in the TPB to include symptom appraisal and a subjective appreciation for treatment properties to capture the additional elements that women utilized when making decisions about using acupuncture for HFs (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Factors Linking Acupuncture with Symptoms of Hot flashes (FLASH Model)

Our study is among the first to explore demographic differences in treatment decisions related to hot flashes by breast cancer survivors. African Americans appear to be much more willing to accept the empirical evidence from historical use as a rationale for their willingness to try acupuncture. While we observed that all African American and most Caucasian patients endorsed acupuncture as a natural alternative, they arrived at this idea from different paths. Compared with Caucasians, African American women were much more likely to voice concerns about existing polypharmacy as a reason why another pill is not an option for them. At the same time, medical co-morbidities such as ongoing pain may also serve as a barrier to using acupuncture for hot flashes for African Americans. Our findings may reflect the clinical reality that African American patients are likely to have greater medical co-morbidity and often their decision of using a therapy for a condition is driven by multiple competing medical needs.

Several limitations of our study need to be acknowledged. Our sample was of limited size and drawn from an urban tertiary medical center. While these factors affect the generalizability of the findings, we did reach saturation of topics (i.e. no new themes emerged) by the twenty-fifth interview and thus feel confident that a larger sample size would not have yielded additional information. We studied decision making around intended use of acupuncture rather than actual use so the factors may not fully capture the complexity of a true clinical decision. Additionally, we conducted research from the perspectives of a primary care physician who practices integrative medicine (JJM) and a medical anthropologist (FB), thus, some degree of bias may present in our interpretation of the data. However, we often negotiated our different world views during research meetings. Finally, qualitative research seeks to identify a range of issues that are important in a group of people. It should not be used to infer causation or to quantify the magnitude of difference between groups in terms of beliefs or behaviors.

Summary and implication

As early detection and better treatments for breast cancer have decreased mortality rates, the survivorship period has become a new area of research and importance. PCPs and oncologists need a range of options for women who are experiencing distressing HFs as a result of their breast cancer treatment. The evaluation of acupuncture for hot flashes is limited and ongoing; thus the evidence base for it is limited with conflicting results.32 This raises the dilemma for physicians to recommend or recommend against acupuncture. In a situation in which there is no clear winner, incorporating patients’ perspectives may lead to more satisfied decision making and outcomes. Our study found that acupuncture may be more congruent with some women’s preferences for natural approaches to symptom management, thereby minimizing the need for additional medication. Clinicians need to understand that perceptions about the attributes of acupuncture are likely to vary according to racial group and symptom burden. In establishing the effectiveness of acupuncture in the real world, researchers must account for this variation in the acupuncture interventions that they test. As PCPs play a critical role in decision support for cancer survivors, this understanding may help facilitate patient-centered communication in assisting patients to choose therapeutic options that are acceptable and lead to symptom reduction and better quality of life.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND FUNDING: This project is supported in part by the American Cancer Society CCCDA-08-107-03 and the National Institutes of Health [1K23 AT004112-04]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the American Cancer Society or the National Institutes of Health. We thank the Penn Mixed Methods Research Lab for their assistance with the design, interviewee training, data analysis, and interpretation. We also thank all of the breast cancer survivors for sharing their stories.

Footnotes

CONFLICTING AND COMPETING INTERESTS: The authors declare that they have no conflicting or competing interests.

PRIOR PRESENTATIONS: Podium presentation at the 6th International Society for Complementary Medicine Research Congress, Chengdu, China, May 2011

REFERENCES

- 1.Chalasani P, Downey L, Stopeck AT. Caring for the breast cancer survivor: a guide for primary care physicians. Am J Med. 2010 Jun;123(6):489–495. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA, Cordova M, et al. Hot flashes in postmenopausal women treated for breast carcinoma: prevalence, severity, correlates, management, and relation to quality of life. Cancer. 1998 May 1;82(9):1682–1691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carpenter JS, Johnson D, Wagner L, Andrykowski M. Hot flashes and related outcomes in breast cancer survivors and matched comparison women. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002 Apr;29(3):E16–E25. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.E16-E25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Su HI, Sammel MD, Springer E, Freeman EW, Demichele A, Mao JJ. Weight gain is associated with increased risk of hot flashes in breast cancer survivors on aromatase inhibitors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010 Feb 25; doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0802-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tchen N, Juffs HG, Downie FP, et al. Cognitive function, fatigue, and menopausal symptoms in women receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Nov 15;21(22):4175–4183. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savard J, Davidson JR, Ivers H, et al. The association between nocturnal hot flashes and sleep in breast cancer survivors. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004 Jun;27(6):513–522. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodwin PJ, Ennis M, Pritchard KI, et al. Adjuvant treatment and onset of menopause predict weight gain after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 1999 Jan;17(1):120–129. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mao JJ, Bowman MA, Stricker CT, et al. Delivery of survivorship care by primary care physicians: the perspective of breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Feb 20;27(6):933–938. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kligman L, Younus J. Management of hot flashes in women with breast cancer. Curr Oncol. 2010 Jan;17(1):81–86. doi: 10.3747/co.v17i1.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmberg L, Anderson H. HABITS (hormonal replacement therapy after breast cancer--is it safe?), a randomised comparison: trial stopped. Lancet. 2004 Feb 7;363(9407):453–455. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15493-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pandya KJ, Raubertas RF, Flynn PJ, et al. Oral clonidine in postmenopausal patients with breast cancer experiencing tamoxifen-induced hot flashes: a University of Rochester Cancer Center Community Clinical Oncology Program study. Ann Intern Med. 2000 May 16;132(10):788–793. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-10-200005160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loprinzi CL, Michalak JC, Quella SK, et al. Megestrol acetate for the prevention of hot flashes. N Engl J Med. 1994 Aug 11;331(6):347–352. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408113310602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quella SK, Loprinzi CL, Sloan JA, et al. Long term use of megestrol acetate by cancer survivors for the treatment of hot flashes. Cancer. 1998 May 1;82(9):1784–1788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bertelli G, Venturini M, Del Mastro L, et al. Intramuscular depot medroxyprogesterone versus oral megestrol for the control of postmenopausal hot flashes in breast cancer patients: a randomized study. Ann Oncol. 2002 Jun;13(6):883–888. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pandya KJ, Morrow GR, Roscoe JA, et al. Gabapentin for hot flashes in 420 women with breast cancer: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2005 Sep 3–9;366(9488):818–824. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67215-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loprinzi CL. 900 mg daily of gabapentin was effective for hot flashes in women with breast cancer. ACP J Club. 2006 Mar-Apr;144(2):41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stearns V, Slack R, Greep N, et al. Paroxetine is an effective treatment for hot flashes: results from a prospective randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Oct 1;23(28):6919–6930. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stearns V, Hayes DF. Approach to menopausal symptoms in women with breast cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2002 Apr;3(2):179–190. doi: 10.1007/s11864-002-0064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loprinzi CL, Kugler JW, Sloan JA, et al. Venlafaxine in management of hot flashes in survivors of breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000 Dec 16;356(9247):2059–2063. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stearns V, Ullmer L, Lopez JF, Smith Y, Isaacs C, Hayes D. Hot flushes. Lancet. 2002 Dec 7;360(9348):1851–1861. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11774-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson HD, Vesco KK, Haney E, et al. Nonhormonal therapies for menopausal hot flashes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama. 2006 May 3;295(17):2057–2071. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly CM, Juurlink DN, Gomes T, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and breast cancer mortality in women receiving tamoxifen: a population based cohort study. BMJ. 2010;340:c693. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ganz PA, Greendale GA, Petersen L, Zibecchi L, Kahn B, Belin TR. Managing menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000 Jul 5;92(13):1054–1064. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.13.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kronenberg F, Fugh-Berman A. Complementary and alternative medicine for menopausal symptoms: a review of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2002 Nov 19;137(10):805–813. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-10-200211190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boon HS, Olatunde F, Zick SM. Trends in complementary/alternative medicine use by breast cancer survivors: comparing survey data from 1998 and 2005. BMC Womens Health. 2007;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenlee H, Kwan ML, Ergas IJ, et al. Complementary and alternative therapy use before and after breast cancer diagnosis: the Pathways Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009 Oct;117(3):653–665. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0315-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mao JJ, Palmer CS, Healy KE, Desai K, Amsterdam J. Complementary and alternative medicine use among cancer survivors: a population-based study. J Cancer Surviv. 2011 Mar;5(1):8–17. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0153-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker EM, Rodriguez AI, Kohn B, et al. Acupuncture versus venlafaxine for the management of vasomotor symptoms in patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Feb 1;28(4):634–640. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.5150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hervik J, Mjaland O. Acupuncture for the treatment of hot flashes in breast cancer patients, a randomized, controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009 Jul;116(2):311–316. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang MI, Nir Y, Chen B, Schnyer R, Manber R. A randomized controlled pilot study of acupuncture for postmenopausal hot flashes: effect on nocturnal hot flashes and sleep quality. Fertil Steril. 2006 Sep;86(3):700–710. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.02.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nedstrand E, Wijma K, Wyon Y, Hammar M. Vasomotor symptoms decrease in women with breast cancer randomized to treatment with applied relaxation or electro-acupuncture: a preliminary study. Climacteric. 2005 Sep;8(3):243–250. doi: 10.1080/13697130500118050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee MS, Kim KH, Choi SM, Ernst E. Acupuncture for treating hot flashes in breast cancer patients: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009 Jun;115(3):497–503. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0230-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee MS, Shin BC, Ernst E. Acupuncture for treating menopausal hot flushes: a systematic review. Climacteric. 2009 Feb;12(1):16–25. doi: 10.1080/13697130802566980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuyama H, Nagao K, Yamakawa GI, Akahoshi K, Naito K. Retroperitoneal hematoma due to rupture of a pseudoaneurysm caused by acupuncture therapy. J Urol. 1998 Jun;159(6):2087–2088. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)63262-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goddard G, Shen Y, Steele B, Springer N. A controlled trial of placebo versus real acupuncture. J Pain. 2005 Apr;6(4):237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Godin G, Beaulieu D, Touchette JS, Lambert LD, Dodin S. Intention to encourage complementary and alternative medicine among general practitioners and medical students. Behav Med. 2007 Summer;33(2):67–77. doi: 10.3200/BMED.33.2.67-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirai K, Komura K, Tokoro A, et al. Psychological and behavioral mechanisms influencing the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2008 Jan;19(1):49–55. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balneaves LG, Truant TL, Kelly M, Verhoef MJ, Davison BJ. Bridging the gap: decision-making processes of women with breast cancer using complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) Support Care Cancer. 2007 Aug;15(8):973–983. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0282-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong-Kim E, Merighi JR. Complementary and alternative medicine for pain management in U.S.- and foreign-born Chinese women with breast cancer. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007 Nov;18(4 Suppl):118–129. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Canales M, Geller B. Surviving breast cancer: the role of complementary therapies. Fam Community Health. 2003 Jan-Mar;26(1):11–24. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200301000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boon H, Brown JB, Gavin A, Kennard MA, Stewart M. Breast cancer survivors' perceptions of complementary/alternative medicine (CAM): making the decision to use or not to use. Qual Health Res. 1999 Sep;9(5):639–653. doi: 10.1177/104973299129122135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lau RR. Cognitive representations of health and illness, Handbook of Health Behavior Research. New York: Plenum Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 44.DiGiacomo SM. Can there be a "cultural epidemiology"? Med Anthropol Q. 1999 Dec;13(4):436–457. doi: 10.1525/maq.1999.13.4.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garro LC. Remembering what one knows and the construction of the past: A comparison of cultural consensus theory and cultural schema theory. Ethos. 2000;28(3):275–319. [Google Scholar]