Abstract

HIV is a health issue for women offenders who are at particularly high risk. Women's prisons can be opportune settings for HIV prevention interventions. How women perceive partner relationships could be central to targeting HIV interventions. Consequently, this study examines changes in women offenders' risky relationships. Baseline and follow-up data are presented from 344 women offenders. Intent-to-treat analysis is used as well as analysis of covariance to control for baseline values. Findings indicate that women released to the community from prison who were randomized into the prevention intervention were significantly more likely to report changes in five of seven risky relationship thinking myths. Findings suggest that a relationship theory–based prevention intervention for reducing HIV risk could be promising for women offenders reentering the community after prison. Additional research is suggested.

The HIV virus is more prevalent among offenders than in the general U.S. population (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2005), with about 25 percent of all HIV-infected individuals cycling through the criminal justice system annually (Hammett, Harmon, & Rhodes, 2002). Women are the fastest growing group of U.S. prisoners (Harrison & Beck, 2006), and HIV risks increase when they return to the community (Re-Entry Policy Council, 2005). These risks include sex exchange (Cotton-Oldenburg, Martin, Jordan, Sadowski, & Kupper, 1997); sharing drug injection equipment (Cotton-Oldenburg, Jordan, Martin, & Kupper, 1999); engaging in unprotected sex with multiple partners (Hankins et al., 1994; Staton-Tindall et al., 2011); and inconsistent condom use (Epperson et al., 2010; Knudsen et al., 2008).

In response to the HIV risks faced by women, gender-specific HIV prevention interventions have been developed (see Surrat & Inciardi, 2001; Vigilante et al, 1999; Weschberg, Dennis, & Stevens, 1998), as have targeted interventions that focus on practicing safer sex (Schilling, El-Bassel, Gilbert, & Glassman, 1993; Schilling, El-Bassel, Leeper, & Freeman, 1991). In addition, HIV prevention interventions have been developed specifically for women offenders (St. Lawrence et al., 1997; Vigilante et al., 1999). However, these interventions have not targeted risky relationships.

Risky relationships are common among women offenders and can contribute to criminality (Khan et al., 2011; Knudsen et al., 2008; Millay et al., 2009; Sheridan, 1996; Staton-Tindall et al., 2011). Women offenders can have complicated histories of emotional, sexual, and/or physical abuse relationships, which have been related to criminal activities and accompanying risk behaviors (Bond & Semaan, 1996; Millay, et al., 2009; Staton-Tindall, et al., 2007b). Covington (1998, 2008) promotes the idea that relationships can increase the likelihood of a woman's risky thinking and supports Miller's Relational Model (Miller, 1976), which suggests that women develop a sense of self through relationships and strive to maintain connectedness (Finkelstein & Piedade, 1993), For this study, “risky” is defined as hazardous knowledge, attitudes, or behaviors that are associated with a woman's drug use and sexual encounters. Women can engage in behaviors they perceive will sustain and enhance relationships even if the relationships are risky (Jones, 2006; Staton-Tindall et al., 2007a). Given the complicated histories that can be characterized by problematic relationships, women offenders can develop flawed thinking, which is what we call risky relationship thinking myths (Leukefeld et al., 2009).

The purpose of this study is to examine changes in risky relationship thinking myths associated with HIV among women offenders transitioning from prison to the community. It was expected that a targeted prevention intervention would increase positive changes in the HIV relationship thinking myths at 3-month follow-up.

INTERVENTION

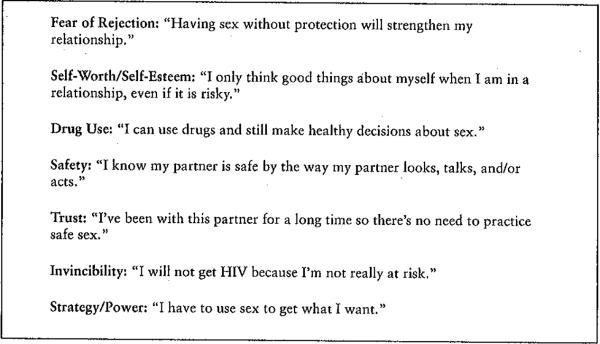

As part of the study, an educational intervention was developed, which is grounded in risky relationship thinking myths, called Reducing Risky Relationships for HIV (RRR). Conceptually, the intervention helps women offenders use relationship thinking myths in their decision-making process to cognitively generate alternatives to risky thinking in order to make healthier and safer decisions about risky sex and drug use. A risky thinking myth is flawed thinking associated with a woman's drug use and sexual behavior. A unique component of the intervention is that each thinking myth targets a specific relationship experience. In other words, a risky partner relationship along with risky thinking can increase a woman's vulnerability to HIV, for example, to engage in sex and/or drug use to get what she needs or wants. Thus, the desire to sustain a relationship may override a woman's ability to clearly assess a partner's risk factors (Jones, 2006; Morrill, Ickovics, Golubchikov, Beren, & Rodin, 1996).

The intervention was developed in two phases: six focus groups that identified relationships, beliefs, and assumptions which could decrease women's abilities to refuse and/or avoid HIV risk as well as a pilot; these are described in more detail by Staton-Tindall and colleagues (2007a). For the focus groups, facilitators used a script to guide the groups. After consenting, 56 women participated. Transcripts were analyzed and themes coded. This phase was followed by a meeting of women substance abuse treatment clinicians and researchers who identified key themes. After a pilot, these themes were formalized into seven risky relationship thinking myths (see Figure 1) that were used to tailor an intervention to increase a woman's ability to protect herself against HIV.

FIGURE 1.

Seven Risky Relationships Thinking Myths

A manual (available from the corresponding author) was developed. The intervention consists of five 90-minute prison-based group sessions and one face-to-face or telephone session after community reentry. The manual incorporates relationship thinking to promote safety. Each of the prison-based group intervention sessions includes didactic and skill-building exercises focused on each thinking myth. In addition, session one incorporates HIV prevention information from the NIDA HIV intervention (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1995).

To ensure fidelity, women who delivered the intervention were trained to use the manual and received weekly supervision from one person. Bi-weekly cross-site conference calls updated implementation, reviewed data, and resolved issues. Adherence was high since almost three-fourths of those randomized to the intervention attended all five sessions (Havens et al., 2009).

METHODS

The two-arm randomized study was conducted between March 2007 and December 2008 as part of the Criminal Justice Drug Abuse Treatment Studies (CJ-DATS) (Fletcher, 2003). Consenting women offenders were randomized into either (1) the prevention intervention group, which received five prison-based sessions that began about six weeks before community reentry and one telephone or face-to-face community booster session, or (2) the comparison group, which received an AIDS awareness video titled “Drug Abuse and HIV: Reaching Those at Risk,” a 17-minute video that features HIV/AIDS risk-reduction information (National Clearinghouse for Alcohol and Drug Information, NCADI Stock #VHS-74). The prevention intervention group also received the video.

Incarcerated women were recruited from four state prisons in Connecticut, Delaware, Kentucky, and Rhode Island (Havens et al., 2009; Staton-Tindall et al., 2007a). Before each monthly recruitment session, a list of women scheduled for community reentry within six to eight weeks received letters about the study screening sessions. Eligibility criteria were: female, age 18 and older, consenting to participate, reporting at least weekly substance use before incarceration, and not prescribed antipsychotics. After consenting, 444 women were randomized using the Research Randomizer (2010). Of the 444 women who were randomized, 15% (n = 66) were not released from prison and were not eligible for follow-up, which yielded a sample of 378. Among the 378 released to the community, the follow-up rate was 90.8% for the 3-month interview, resulting in the final sample of 344 (77.5% of the 444 who consented and were randomized). Follow-up rates did not differ significantly by site or study condition (data not reported here). Women received $20 for completing the baseline interview and an HIV test, as well as at follow-up interview. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Brown University, the University of Connecticut, the University of Delaware, and the University of Kentucky. Baseline data were collected in private prison visitation rooms.

MEASURES

An interviewer-administered questionnaire was used by trained interviewers to collect information that included the following measures:

Demographics

Demographic characteristics included race/ethnicity (White, African American, Hispanic, other), marital status (married/cohabitating, never married, and separated/divorced/widowed), employment before incarceration (full-time, part-time, or unemployed), education (median years), number of children, median number of arrests, and substance use.

HIV/HCV

Oral swabs detected HIV antibodies (OraQuick® ADVANCE™ Rapid HIV-1/2 Antibody Test (Bethlehem, PA), and for HCV, blood samples were tested for the presence of anti-HCV using Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) (Home Access Health Corporation, Hoffman Estates, IL). Pre- and post-test counseling followed Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines (CDC, 2006). Interviewers completed state training to provide HIV testing and pre- and post-test counseling.

HIV knowledge

HIV knowledge was measured using the HIV Knowledge Questionnaire (18-item version) (HIV-KQ-18) (Carey & Schroder, 2002). This 18-item true/false scale was used at baseline and 90-day follow-up, with Cronbach's alphas of .75 and .89 and test-retest of .76 and .94, respectively.

AIDS risks

AIDS risks were measured by the NIDA Risk Behavioral Assessment (RBA) at baseline and the Risk Behavior Follow-up Assessment (RBFA) at follow-up. The RBA and the RBFA include questions on sexual risks of which two were of interest: sex partners and unprotected sex (NIDA, 1995). At baseline, women were asked to report the number of sex partners during the six months before incarceration as well as the number of unprotected sexual encounters without a condom in the six-months before incarceration. At follow-up, women were asked to report the number of sex partners and the number of unprotected sexual encounters in the previous 3 months.

Relationship power

Relationship power was measured by the 23-item Sexual Relationship Power Scale (SRPS) (Pulerwitz, Amaro, Dejong, Gortmaker, & Rudd, 2002) which includes two subscales: the 15-item Relationship Control (RC) and 8-item Decision-Making Dominance (DMD) subscales. Scale items measure relationships, safer sex negotiation, control in relationships, and decision making to examine relationship power and sexual practices. Internal reliability for the total scale is 0.84, Relationship Control (.86), and Decision Making at .62 (Pulerwitz, Gortmaker, & DeJong, 2000).

Self-esteem

Self-esteem was measured by the Rosenberg Scale (Rosenberg, 1965) which has demonstrated reliability and validity in multiple studies to measure self-esteem from low to high, with Cronbach's alphas of .77 to .88 and test-retest of .82 to .85, respectively (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1990).

Thinking myths

Thinking myth measures were developed by the authors. The RRR-HIV scale is 21 items on HIV risk behavior knowledge, which focus on thinking myth risk behaviors (e.g., “Having sex without protection will strengthen my relationship”). Participants rated these statements from 1 to 5, where 1 = “Definitely False”; 2 = “Maybe False”; 3 = “Unsure”; 4 = “Maybe True”; and 5 = “Definitely True.'” To determine possible changes in thinking myths, the RRR Thinking Myths Scale (RRR-TMS) was also developed by the authors. The RRR-TMS is 11 items that explored attitudes on each thinking myth (e.g., “Sex without protection will strengthen my relationship”). Participants were asked to rate each statement from 1 to 10, with 1 corresponding to “Definitely True” and 10 to “Definitely False.” These scales were administered at baseline and at 3-month follow-up.

Condom use

The Condom Self-Efficacy Scale, a 28-item scale, was used to examine confidence about purchasing and using condoms as well as negotiating condom use with a new partner and has been demonstrated to predict condom use (Brafford & Beck, 1991), with a Cronbach's alpha of .91 and test-retest correlation of .81 (Kowaleski, Longhshore, & Anglin, 1994).

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses were used for group comparisons, regardless of participation. For baseline measures, women in the prevention intervention and the comparison groups were compared using contingency table analyses and the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test for categorical and continuous variables. For change analyses, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to compare groups on the targeted risky relationship thinking myths for change at 3-month follow-up, adjusting for baseline measures of each variable and for baseline cocaine and heroin use, which were the only baseline measures that differed between groups. A post-estimation command (ω2) was used to calculate the effect sizes for each change variable using ANCOVA. It should be noted that for effect sizes estimated via ω2, small, medium, and large effect sizes correspond to the values of 0.01, 0.06, and 0.14, respectively (Cohen, 1988). STATA, version 10.0 (College Station, TX), was used for analyses.

RESULTS

The median participant age was 34.6 (interquartile range (IQR): 27.7 to 41.7). Most women were white (70.5%), averaged 11 years of education (IQR: 10 to 12), and had two children (IQR: 1 to 3). Most had never been married and were unemployed before prison. The overall HIV and HCV positive rates were 1.6% and 25.4%, respectively. There were no significant differences between the intervention and the comparison groups at baseline measures on HIV (1.4% and 1.9%, respectively) and HCV (28,2% and 25,7%, respectively). There were also no significant differences in demographic characteristics between the intervention (n = 226, 50.9%) and the comparison group (n = 218, 49.1%). However, twice as many intervention group women reported daily heroin use (10.2% versus 5.0%, p = 0.05) and cocaine use (18.6% versus 9.2%, 0.006) in the 30 days before prison.

There were few baseline differences between the groups on HIV knowledge, sexual relationship power, self-esteem, and knowledge on selected domains for most thinking myths (data not presented here). For two of the thinking myths, women in the comparison group were significantly more likely than women in the prevention intervention group to indicate that the following statement was true: “I don't make healthy choices about HIV protection when I use drugs” (Drug Use Thinking Myth), and that this statement was false: “I know my partner is safe by how he/she looks” (Safety Thinking Myth).

When 3-month changes in thinking myths were examined, women in the intervention group were significantly more likely to report overall increased knowledge of HIV risk behaviors (HIVKQ-18) (see Table 1). There was also a significant greater increase in self-esteem (Self-Worth Thinking Myth) (p = 0.032). For the Sexual Relationship Power Scale (SRPS), the intervention group reported higher sexual relationship power and relationship control (Strategy/Power Thinking Myth) at follow-up, after adjusting for baseline SRPS measures as well as baseline cocaine and heroin use. Medium to large effect sizes were seen for HIV risk knowledge, which were associated with a thinking myth. Specifically, women in the intervention group were significantly more likely to indicate that a person can get HIV through sharing works (ω2 = 0.13) (Drug Use Thinking Myth); that male and female condoms should not be used together (ω2 = 0.32) (Fear of Rejection Thinking Myth); and that women who use drugs do not make healthy choices about HIV protection (ω2 = 0.12) (Drug Use Thinking Myth). Women in the intervention group were also significantly more likely to indicate that knowledge improved in certain domains: the thinking myths “I can use drugs and still make healthy choices about sex” (Drug Use Thinking Myth) and “I know my partner is safe by the way they look/talk/act” (Safety Thinking Myth) were false.

TABLE 1.

90-Day Change for the Intervention and Comparison Condition, Adjusting for Baseline Values (n = 344)

| Intervention | Comparison | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| n = 178 | n = 166 | Effect Size | ||||

|

|

||||||

| mean | SE | mean | SE | R | p-value | |

| Number sex partners in past 90 days | 1.23 | 0.33 | 1.57 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 0.494 |

| Number unprotected sexual encounters in past 90 days | 17.1 | 3.21 | 22.9 | 3.33 | 0.04 | 0.215 |

| HIV Knowledge Questionnaire | 16.9 | 0.10 | 16.5 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.024 |

| Condom Self-Efficacy Scale | 89.7 | 1.06 | 86.9 | 1.11 | 0.07 | 0.066 |

| Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale | 21.0 | 0.35 | 19.9 | 0.36 | 0.09 | 0.032 |

| HIV Knowledgea | ||||||

| There is a cure for HIV | 1.20 | 0.06 | 1.34 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.142 |

| There is no vaccination for hepatitis B | 1.99 | 0.10 | 2.00 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.935 |

| Can get HIV through sharing works | 4.77 | 0.07 | 4.50 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.008 |

| Crack/cocaine users at increased HIV risk | 4.72 | 0.08 | 4.50 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.053 |

| Female/male condom not used together | 3.93 | 0.12 | 2.79 | 0.12 | 0.32 | <0.001 |

| Women use drugs make healthy choices | 1.63 | 0.10 | 2.01 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.011 |

| Unhealthy relationships increase HIV risk | 4.66 | 0.07 | 4.57 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.396 |

| Women use drugs to keep relationship | 4.75 | 0.05 | 4.66 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.296 |

| Having sex w/o protection strengthen relationship | 1.31 | 0.07 | 1.45 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.180 |

| Can't get HIV from unprotected sex 1 time | 1.37 | 0.07 | 1.18 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.066 |

| Sexual Relationship Power Scale | 2.83 | 0.04 | 2.69 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.018 |

| Relationship Control subscale | 2.99 | 0.05 | 2.83 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.019 |

| Decision-Making Dominance subscale | 2.69 | 0.05 | 2.56 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.055 |

| Thinking Mythsb | ||||||

| Sex w/o protection will strengthen relationship | 9.39 | 0.14 | 9.32 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.744 |

| Using drugs w/partner strengthen relationship | 9.71 | 0.10 | 9.60 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.423 |

| Only think good things re: self in relationship | 8.07 | 0.24 | 7.94 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.698 |

| Think good things re: self if not in relationship | 2.62 | 0.23 | 3.13 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.133 |

| Use drugs & make healthy choices re: protection | 9.00 | 0.20 | 8.11 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.002 |

| Unhealthy choices re: protection when using drugs | 4.27 | 0.29 | 5.40 | 0.31 | 0.13 | 0.009 |

| Know partner safe from HIV by looks | 9.84 | 0.09 | 9.58 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.058 |

| Know partner safe from HIV by how talks | 9.87 | 0.10 | 9.52 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.014 |

| Know partner safe from HIV by how acts | 9.85 | 0.09 | 9.57 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.032 |

| Will not get HIV because not at risk | 8.75 | 0.22 | 8.13 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.048 |

| Will get HIV because at risk | 6.54 | 0.19 | 6.54 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.245 |

Note.

1 = Definitely False, 2 = Maybe false, 3 = Unsure, 4 = Maybe True, 5 = Definitely True.

1 = Definitely True through 10 = Definitely False.

DISCUSSION

HIV is a health issue for women offenders. However, only about half of correctional agencies test for HIV (Oser, Staton-Tindall, & Leukefeld, 2007) even though periods of incarceration provide opportunities to intervene. Nevertheless, there are few HIV prevention interventions for women offenders and fewer target women's relationships, or risky relationship thinking myths, associated with HIV. The intervention examined in this study was developed as a theory-based approach to change women's HIV risky relationship thinking myths.

In this study, women in the intervention group experienced positive changes in HIV knowledge when compared with women in the comparison group. Although studies have reported no association between HIV knowledge and risky sexual behavior (Bachanas et al., 2002), HIV knowledge remains a key feature of interventions (Meader, Li, Des Jarlais, & Pilling, 2010). A recent Cochrane Review of HIV interventions adds that knowledge-based interventions were effective at reducing HIV risky behaviors (Meader et al., 2010).

When the seven Thinking Myths were examined, women reported gains in HIV knowledge and positive changes in attitudes associated with sexual risks. Specifically, compared to women in the comparison group, self-esteem rates at 90 days post-release were significantly higher for women in the intervention group (i.e., Self Worth Thinking Myth). Women's lower self-esteem/self-worth has been associated with having sex for pay, sexual risk-taking, condom use attitudes, condom self-efficacy, and overall HIV risk behavior (Sterk, Klein, & Elifson, 2004). These self-esteem differences could be related to the intervention strategies which target the thinking myth, “I only think good things about myself when I am in a relationship, risky or not.” The intervention could help women understand and use techniques to enhance control and protection in risky situations.

Another variable of interest was relationship power (Strategy/Power Thinking Myth). The intervention significantly enhanced women's relationship power when outcomes from the Sexual Relationship Power Scale (SRPS) were examined. Previous studies have demonstrated that low relationship power impedes a woman's ability to negotiate safe sex (Soet, Dudley, & Dilorio, 1993; Woolf & Maisto, 2008). Although the increase in relationship power among intervention group participants when compared with the comparison group did not result in significantly fewer unprotected sexual encounters at 3-month follow-up, intervention group women reported 25% fewer unprotected sexual encounters. Consequently, increased relationship power may have helped women in the intervention group when compared with the comparison group negotiate condom use. Additional research including women's focus groups could help to understand how changes could lead to reduced risks.

When the Fear of Rejection thinking myth (“Having sex without protection will strengthen my relationship”) was examined, women in the intervention group when compared with the comparison group reported that sexual protection (i.e., use of condoms) should be used when drugs are involved. In addition, the intervention group when compared to the comparison group reported the need for enhanced safety (Safety Thinking Myth) to consider the ways a partner talks and acts, but not how a partner looks. Perhaps reentering women don't think the way a partner looks is important since these women had been away from the community. Further research is needed to better understand these findings.

There were two thinking myths, the Trust thinking myth and the Invincibility thinking myth, for which none of the measures showed differences between the intervention and the comparison groups. Perhaps the Trust thinking myth—“I've been with this partner for a long time so there's no need to practice safe sex”—is less relevant for women reentering the community from prison since these women had not been in recent long-term relationships. Consequently, reentering women may not think that trust is important since they have been separated, and practicing safe sex may not be important at that time. This may be similar for the Invincibility Myth—“I will not get HIV because I'm not really at risk”—since reentering women may believe that they are at little risk for HIV at reentry. This is an area for further research that could add to understanding why reentering women do not think they are at risk for HIV during reentry.

Although additional studies are needed, this study suggests that understanding women's risky relationships and thinking myths could help women change their risky relationships. This study supports the assumption that a prevention intervention focused on thinking myths is promising for HIV prevention among women offenders who are at high risk for HIV. The group format and relatively brief nature of the intervention could make the intervention an attractive choice for women offenders.

LIMITATIONS

There are several study limitations. The first is that study participants were not a random sample of women offenders since four prisons were purposively selected. However, every woman eligible for release was approached in each of the prisons and asked to voluntarily participate in the study. Second, data are self-reported, which can have biases related to recall and truthfulness. There are also additional issues of recall associated with self-reported measures of risky sexual and other behaviors that occurred before prison. Further, since questions about sexual risk behaviors and drug use focused on specific and potentially sensitive activities, the possibility exists that some participants, those who are less comfortable discussing these issues, may underreport. It is also more difficult to establish the validity of self-reported sexual behaviors because there are no biological markers. However, self-reported risky sexual behaviors are commonly used in research studies.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite these limitations, this study suggests that risky relationships and thinking myths could be promising. Additional research should examine the utility of risky relationship thinking myths. It should also be noted that the study was successfully implemented in four different state prisons. Clearly, the involved prison officials were aware of the importance of developing, interventions for women offenders and understood that reentry is an opportunity. Reentry situations can be challenging for women and for their relationships when partner needs are considered. For example, although not examined in this study, relationships and thinking myths at reentry could be more strenuous for women with children, which averaged two for study participants. In addition, relationship thinking myths could be more strained, but in a different way, for women who reenter the community without a partner or with multiple partners and/or for women who engage in sex trading.

HIV risky relationship thinking myths is a unique focus of an intervention. In the current study, changes were reported for five of the seven thinking myths. A better understanding of changes in sexual relationship risk thinking myths as well as other risky relationship thinking myths on behavior outcomes—such HIV behaviors and drug use—is needed. Incorporating booster sessions in future studies could also be important.

This study adds to understanding the importance of women offenders' HIV risks and relationship thinking myths as well as the importance of prison settings for future research, There is also a need for studies to better understand the association and interaction of risky thinking, partner relationships, and self-esteem. This understanding is not only important theoretically but also practically to develop women's focused interventions. Future research could examine women's trust within relationships, particularly risky relationship thinking myths and could consider possible relationship similarities and/or differences associated with factors such as criminality during community reentry. In addition, future analysis should explore thinking myths as mediators or moderators of HIV risk behaviors. Finally, risky relationship thinking myths can provide a way to conceptually ground interventions and help women think about HIV risks, which this study supports as being common among women offenders.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded under a cooperative agreement (U01 DA16205) from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIH/NIDA). The authors gratefully acknowledge the following CJ-DATS collaborating Research Centers for their hard work in collecting data for this study: National Development and Research Institutes, Inc., Center for Therapeutic Community Research and Center for the Integration of Research and Practice; University of Delaware, Center for Drug and Alcohol Studies; University of Kentucky, Center on Drug and Alcohol Research; University of California at Los Angeles, Integrated Substance Abuse Programs; and Texas Christian University, Institute of Behavioral Research. The authors also acknowledge the collaborative contributions by federal staff from NIDA, members of the Coordinating Center (Virginia Commonwealth University and University of Maryland at College Park, Bureau of Governmental Research), and the other Research Center grantees of the NIH/NIDA CJ-DATS Cooperative (Brown University, Lifespan Hospital; Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services; and University of Miami, Center for Treatment Research on Adolescent Drug Abuse). In addition, we gratefully acknowledge the individuals who volunteered as research subjects for this study and for their cooperation, which made the research possible. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIH/NIDA or other participants in CJ-DATS, including the correctional agencies that participated in this study.

Footnotes

Copyright of AIDS Education & Prevention is the property of Guilford Publications Inc. and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

REFERENCES

- Bachanas PJ, Morris MK, Lewis-Gess JK, Saret-Cuasay EJ, Flores AL, Sirl KS, et al. Psychological adjustment, substance use, HIV knowledge, and risky sexual behavior in at-risk minority females: Developmental differences during adolescence. Journal ofPediatric Psychology. 2002;27:373–384. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.4.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blascovich J, Tomaka J. Measures of self-esteem. In: Robinson J, Shaver P, Wrightsman L, editors. Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes. Academic Press; New York: 1990. pp. 115–160. [Google Scholar]

- Bond L, Semaan S. At risk for HIV infection: Incarcerated women in a county jail in Philadelphia. Women's Health. 1996;24(4):27–45. doi: 10.1300/j013v24n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brafford LJ, Beck KH. Development and validation of a condom self-efficacy scale for college students. Journal of American College Health. 1991;39:219–225. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1991.9936238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics Prisoners in 2004. 2005 Retrieved July 31, 2007, from http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/abstract/p04.htm.

- Carey MP, Schroder KEE. Development and psychometric evaluation of the brief HIV Knowledge Questionnaire. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2002;14(2):172–182. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.2.172.23902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2006;55(RR-14):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton-Oldenburg NU, Jordan K, Martin SL, Kupper L. Women inmates' risky sex and drug behaviors: Are they related? American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1999;25(1):129–149. doi: 10.1081/ada-100101850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton-Oldenburg NU, Martin SL, Jordan BK, Sadowski SL, Kupper L. Preincarceration risky behaviors among women inmates: Opportunities for prevention. Prison Journal. 1997;77(3):281–294. [Google Scholar]

- Covington S. Women and addiction: A trauma-informed approach. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;5:377–385. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington S. Women in prison: Approaches in the treatment of our most invisible population. Women and Therapy. 1998;21(1):141–155. [Google Scholar]

- Epperson MW, Khan MR, Miller DP, Perron BE, El-Bassel N, Gilbert L. Assessing criminal justice involvement as an indicator of human immunodeficiency virus risk among women in methadone treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;38(4):375–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein N, Piedade E. The relational-model and the treatment of addicted females. Counselor Magazine. 1993 May-Jun;:8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher B. The National Criminal Justice Drug Abuse Treatment Studies. Offender Substance Abuse Report. 2003;3:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hammett TM, Harmon P, Rhodes W. The burden of infectious disease among inmates and releasees from US correctional facilities, 1997. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:189–194. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankins CA, Gendron S, Handley MA, Richard C, Tung M,T, O'Shaughnessy M. HIV infection among women in prison: An assessment of risk factors using a non-nominaf methodology. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(10):1637–1640. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.10.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PM, Beck AJ. Prison and jail inmates at midyear 2005. US DOJ, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; Washington, DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Havens JR, Leukefeld CG, Oser CB, Staton-Tindall M, Knudsen HK, Mooney J, Duvall JL, Clarke JG, Frisman L, Surratt HL, Inciardi JA. Examination of an interventionist-led HIV intervention among criminal justice-involved female prisoners. Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2009;5(3):245–273. doi: 10.1007/s11292-009-9081-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. Sex scripts and power: A framework to explain urban women's HIV sexual risk with main partners. Nursing Clinics of North America. 2006;41(3):425–436. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MR, Behrend L, Adimora AA, Weir SS, Tisdale C, Wohl DA. Dissolution of primary intimate relationships during incarceration and associations with post-reiease STI/HIV risk behavior in a Southeastern city. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2011;38(1):43–47. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181e969d0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Leukefeld C, Havens JR, Duvall JL, Oser CB, Staton-Tindall M, et al. Partner relationships and HIV risk behaviors among women offenders. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40:471–481. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowaleski MR, Longhshore D, Anglin MD. The AIDS Risk Reduction Model: Examining intentions to use condoms among injection drug users. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1994;24:2002–2027. [Google Scholar]

- Leukefeld CG, Oser CB, Havens J, Staton-Tindall M, Mooney J, Duvall J, Knudsen H. Drug abuse treatment: Beyond prison walls. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2009;5(1):24–30. doi: 10.1151/ascp095124. PMCID: PMC2749213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meader N, Li R, Des Jarlais DC, Pilling S. Psychosocia) interventions for reducing injection and sexual risk behavior for preventing HIV in drug users. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010;(Issue 1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007192.pub2. Art. No. CD007192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millay TA, Satyanarayana VA, O'Leary CC, Crecelius R, Cottler LB. Risky business: Focus group analysis of sexual behaviors, drug use, and victimization among incarcerated women in St. Louis. Journal of Urban Health. 2009;86(5):810–817. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9381-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JB. Toward a psychology of women. Beacon Press; Boston, MA: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Morrill AC, Ickovics JR, Golubchikov VV, Beren SE, Rodin J. Safer sex: Social and psychological predictors of behavioral maintenance and change among heterosexual women. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(4):819–828. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.4.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Risk behavior assessment. NIDA; Rockville, MD: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Oser C, Staton-Tindall M, Leukefeld C. HIV/AIDS testing in correctional agencies and community treatment programs: The impact of internal organizational structure. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;32:301–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Amaro H, DeJong W, Gortmaker SL, Rudd R. Relationship power, condom use and HIV risk among women in the USA. AIDS Care. 2002;4:789–800. doi: 10.1080/0954012021000031868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Gortmaker SL, DeJong W. Measuring sexual relationship power in HIV/STD research. Sex Roles. 2000;42(7–8):637–660. [Google Scholar]

- Re-Entry Policy Council The report of the re-entry policy council. 2005 Retrieved August 5, 2007, from www.reentrypolicy.org.

- Research Randomizer Research randomizer: Free random sampling and random assignment. 2010 Retrieved April 13, 2010, from http://randomizer.org/

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling RF, El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Glassman M. Predictors of changes in sexual behavior among women on methadone. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1993;19:409–423. doi: 10.3109/00952999309001631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling RF, El-Bassel N, Leeper MA, Freeman L. Acceptance of the female condom by Latin and African-American women. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;10:1345–1346. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.10.1345-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan MJ. Comparison of the life experiences and personal functioning of men and women in prison. Families in Society. 1996;77:423–434. [Google Scholar]

- Soet JE, Dudley WN, Dilorio C. The effects of ethnicity and perceived power on women's sexual behavior. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1993;23:707–723. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1999.tb00393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Lawrence JS, Eldridge GD, Shelby MC, Little CE, Brasfield TL, O'Brannon RE. HIV risk reduction for incarcerated women: A comparison of brief interventions based on two theoretical models. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology. 1997;65(3):504–509. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton-Tindall M, Duvall J, Leukefeld C, Oser C. Health, mental health, substance use, and service utilization among rural and urban incarcerated women. Women's Health Issues. 2007b;17(4):183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton-Tindall M, Frisman L, Lin HJ, Leukefeld C, Oser C, Havens JR, Prendergast M, Surratt HL, Clarke J. Relationship influence and health risk behavior among re-entering women offenders. Women's Health Issues. 2011;21(3):230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton-Tindall M, Leukefeld CG, Palmer J, Oser C, Kaplan A, Krietemeyer J, et al. Relationships and HIV risk among incarcerated women. Prison Journal. 2007;87(1):143–165. [Google Scholar]

- Sterk CE, Klein H, Elifson KW. Self-esteem and “at risk” women: Determinants and relevance to sexual and HIV-related risk behaviors. Women's Health. 2004;40:75–92. doi: 10.1300/j013v40n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surratt HL, Inciardi JA. Developing HIV and hepatitis prevention initiatives for women sex workers in Miami, Florida. Health Services Disparities and Addictions Conference; Galveston, Texas. October 31–November 2, 2001; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Vigilante KC, Flynn MM, Affleck PC, Stunkle JC, Merriman NA, Flanigan TP, Mitty JA, Rich JD. Reduction in recidivism of incarcerated women through primary care, peer counseling, and discharge planning. Journal of Women's Health. 1999;8(3):409–415. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1999.8.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Dennis ML, Stevens S. Cluster analysis of women substance abusers in HIV interventions: Characteristics and outcomes. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1998;24(2):239–257. doi: 10.3109/00952999809001711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf SE, Maisto SA. Gender differences in condom use behavior? Sex Roles. 2008;58(9–10):689–701. [Google Scholar]