Introduction

The ability to hear sound is one of the fundamental ways that organisms are able to perceive the external environment. It is speculated that hearing evolved as a distance sense, a function driven by a need for animals to detect potential danger, food, or mates that could not be seen because of darkness or dense foliage. Animals have the ability to sense perturbations in the air, and in vertebrates, the internal ear is a highly developed sensory structure that enables this function. Cats have especially keen hearing [1]. Their ability to hunt, avoid predators and oncoming motor vehicles, and interact with their owners depends on their hearing. Cats with hearing loss and/or deafness are vulnerable to danger.

For terrestrial vertebrates, sound is created by vibrations in air [2]. These vibrations may be characterized by frequency (cycles per second, Hz), which is correlated to the sensation of pitch, the magnitude of the pressure of the vibrations (loudness), their timing (e.g., onset, offset, duration, cadence), and the location. Two ears allow the extraction of important acoustic cues: the ear closer to the sound source will hear the sound sooner (interaural timing difference) and louder (interaural level difference) than the more distant ear. These binaural differences allow the brain to calculate sound location, and survival can depend on knowing if the sound comes from the right or the left. Sound arriving from the front has a different character than sound arriving from behind due to interference by the external ear. This interference is called a head-related transfer function. The cat learns about the transfer functions so that it can also distinguish between sound in the front and back, an ability that is important to survival.

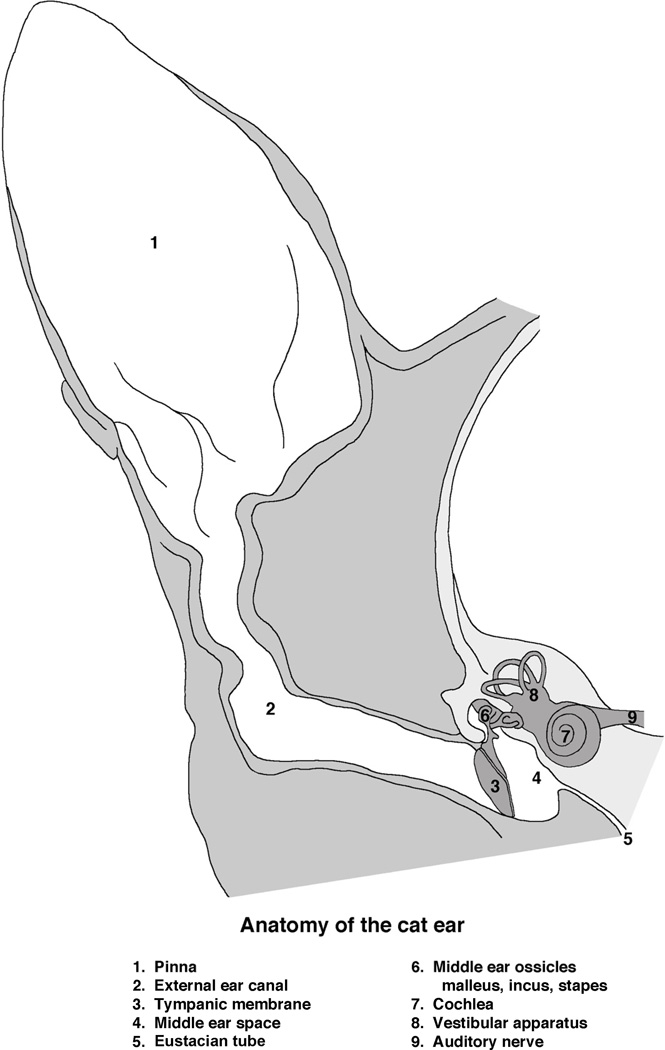

Sound is captured by the pinna, the external portion of the ear, and funneled through the ear canal to the tympanic membrane or eardrum (Fig. 1). The tympanic membrane is mechanically coupled to the three middle ear ossicles – the malleus, incus, and stapes – whose combined function is to deliver the vibrations to the fluid-filled internal ear with the same power as that delivered to the tympanic membrane. The vibrations in air become vibrations in fluid and are transmitted to the sensory hair cell receptors that reside in the organ of Corti. This mechanical signal is converted to neural signals and relayed to the brain by the cochlear (or auditory) branch of cranial nerve VIII (also known as the vestibulocochlear nerve). The brain receives and interprets these signals and the result is what we perceive as hearing.

Mammalian hearing relies on two broad categories of function -- mechanical and electrochemical.

The mechanical component involves the capture of sound by the external ear and its transmission into the fluid-filled cochlea. The vibrations in the fluids mechanically stimulate different regions of the internal ear based on frequency, where these perturbations mechanically stimulate the cochlear hair cell bundle.

The electrochemical component results from hair bundles that border the endolymphatic space. The endolymph has a positive potential (~80 mV) that drives K+ into the cytoplasm of stimulated hair cells. Receptor cell responses are converted to action potentials in fibers of the cochlear nerve and conveyed to the brain. Malfunction of either of these auditory processing components results in hearing loss.

- Two types of hearing loss are identified and considered as separate entities. “Conductive” hearing loss refers to problems of the peripheral auditory system, whereas “sensorineural” hearing loss refers to malfunction of the neuronal components of the auditory system.

- “Conductive” hearing loss results from external ear occlusion, tympanic membrane perforation, ossicular chain discontinuity or fixation, or middle ear infections. For cats, conductive hearing loss is often amenable to improvement with cleaning the external ear canal, antibiotics to clear middle ear infection, or surgical procedures to repair the tympanic membrane or ossicular function.

- “Sensorineural” hearing loss, on the other hand, can result from pathology anywhere along the auditory pathway, from the hair cell receptors to higher order central auditory processing centers. Deafness due to sensorineural hearing loss resembles a train wreck—it can result from many diverse causes but the outcome is always hearing loss.

- Sensorineural deafness can be classified into two broad classes: congenital deafness and acquired deafness.

- Congenital deafness is a condition that exists at birth and often prior to birth, or that develops during the first month of life regardless of etiology. In humans, nearly half of the causes of deafness can be attributed to genetic abnormalities. One-third of these defects is accompanied by identified disorders in other systems, and is considered “syndromic” deafness. The remaining two-thirds, however, are isolated to hearing loss and considered “non-syndromic.”

- Acquired deafness refers to a loss of hearing that is not present at birth but develops during the animal’s lifetime. The causes of acquired hearing loss can be illness (e.g., meningitis), head trauma, ototoxic drugs, and exposure to loud noise. In industrialized society, cats exhibit a significant amount of “normal pathology” that is assumed to arise from street noise [1].

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing of the cat ear. The external ear consists of the pinna (1) and external ear canal (2) that conducts airborne sound to the tympanic membrane (3, ear drum). The tympanic membrane and three middle ear bones (6) occupy the middle ear space (4). These moving parts convert vibrations in air to vibrations in the inner ear (7). The middle ear space is confluent with the pharynx by way of the Eustachian tube (5). Behind the cochlea, the auditory component of the inner ear, lies the vestibular structures (8). The eighth cranial nerve, the auditory-vestibular nerve (9), conducts sensory information from the sense organ to the brain. (Drawn by Catherine Connelly, Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Sydney, Australia.)

Genetics of Deafness

Considerable progress has been made in identifying the genes and genetic loci associated with mammalian deafness. The list of genes is well over one hundred and an updated database of the non-syndromic deafness genes and loci is maintained at the Hereditary Hearing Loss Homepage (http://hereditaryhearingloss.org). With the identification of hereditary deafness genes and the proteins they encode, molecular elements of basic hearing mechanisms emerge. As the function of these identified molecular elements continue to be unraveled, we can begin to understand the remarkable complexity of hearing. Multiple genes interact and express themselves at multiple loci such that rarely is a single gene responsible for the normal functioning of any system. The goal of this chapter is to summarize the function of some of the proteins implicated in hearing and genetic deafness while using the deaf white cat as the model (Fig. 2). The white cat is a good model for study because it has good low frequency hearing like humans, and when deaf, its deafness is naturally occurring, has a genetic basis, and exhibits variable expression.

Figure 2.

Photograph of a congenitally deaf white cat. Note the heterochromia of the irides. This particular cat is healthy with no balance deficiencies; only deafness. (Courtesy of Dr. David K. Ryugo, Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Sydney, Australia).

The deaf white cat has long held a fascination to man, attracting the attention of Charles Darwin, among others [3,4]. The product of a single autosomal dominant locus, White (W), demonstrates pleiotropic effects, including a white coat, blue iris, and deafness, all three of which can be attributed to an absence or abnormality of melanocytes. The correlation between white coat color, blue irises and deafness is, however, imperfect. Thus, white cats exhibit a uniform white coat, although they can be born with a colored spot that fades with age, and they may be either unilaterally or bilaterally deaf, demonstrating varying degrees of severity, from mild to profound. Additionally, their irises are often blue due to the absence of melanin, and the likelihood of deafness has been calculated at 80% with the frequency of blue irises [5,6].

The white, deaf phenotype has been reported in multiple species, including the mouse, dog, mink, horse, rat, Syrian hamster, alpaca, and human [7–19]. Type 2 Waardenburg syndrome most closely describes the phenotype in humans with distinctive hypopigmentation of skin and hair and congenital cochleosaccule dysplasia that resembles the Scheibe deformity. Investigation of the genetic basis for distinctive coat color phenotypes represent some of the earliest mapped and characterized genetic mutations [20]. Early in embryogenesis, melanoblasts, or pigment precursor cells, migrate from the neural crest to the skin, regions of the eye, and the internal ear. Mutations affecting any step in this pathway, be it proliferation, survival, migration or distribution of melanoblasts is often manifested as coat color variation. Genes identified in these early events of pigmentation, many of which were characterized in the mouse white spotting mutants, include Pax3, Mitf, Slug, Ednrb, Edn3, Sox10 and Kit [21–30].

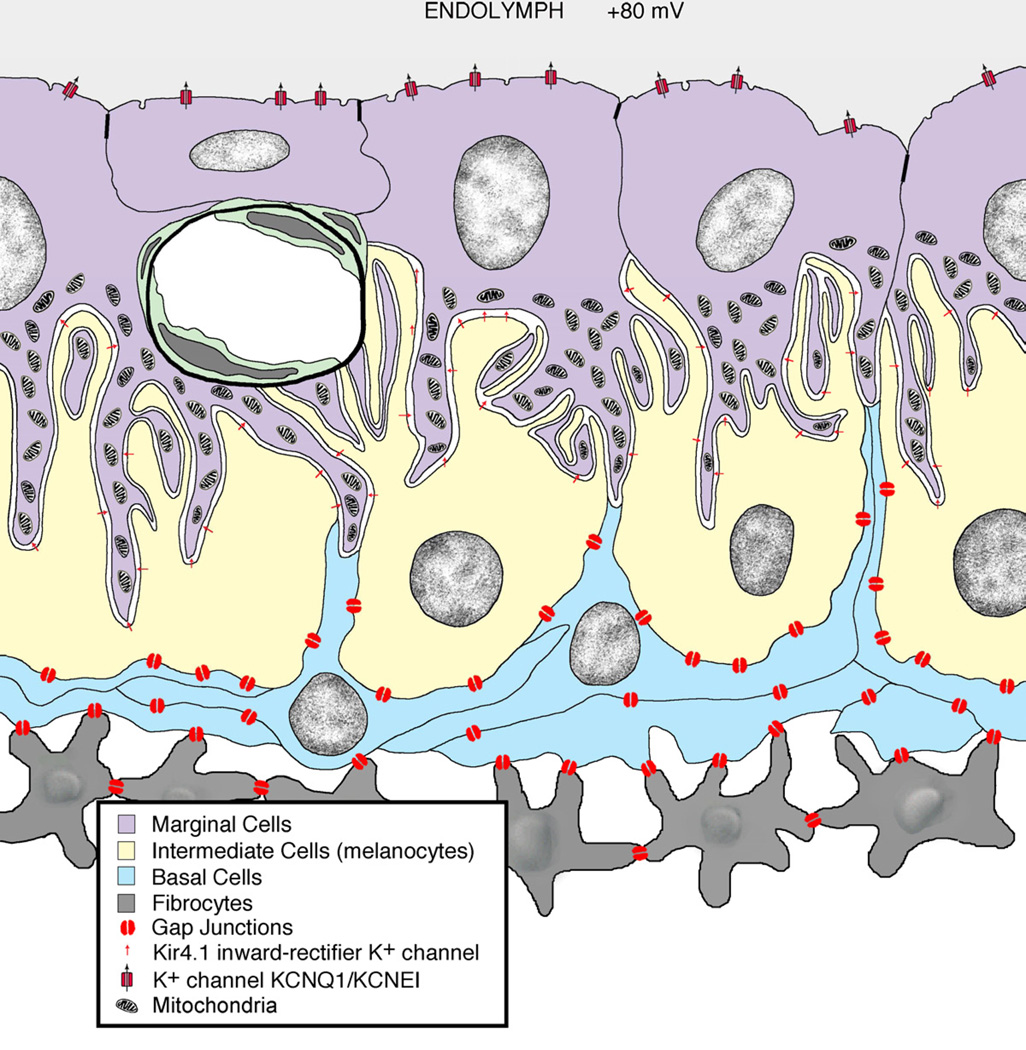

In spite of the long-standing interest in coat color and deafness, only recently has the role of melanocytes in hearing been studied. In the internal ear, melanocytes are largely observed in the stria vascularis, the vascularized epithelium responsible for secreting high levels of K+ into the endolymph, which establishes the endocochlear potential (EP) [31]. The +80 mV EP is crucial for the normal function of the auditory receptor cells. Melanocytes are the only cell type in the stria vascularis to express the potassium channel protein, KCNJ10 (Kir4.1), providing the structural basis for the rate-limiting step that establishes the EP [32]. Knockouts of the Kcnj10 gene in mice eliminate the EP and reduce endolymph potassium concentration, with resultant deafness [32].

The incomplete penetrance for iris color and deafness has made it challenging to interpret an individual’s genetic condition by classic linkage approaches because those who possess the particular gene won’t necessarily exhibit features of the gene [33]. Reduced penetrance is thought to result from a combination of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors, many of which are not known. Our approach to this dilemma is to perform linkage analysis for White in a pedigree segregating for white coat color. Information on the mutational mechanism can be applied to the segregation of deafness in an extended pedigree to examine features associated with the incomplete penetrance for deafness (i.e., the impact of homozygosity vs. heterozygosity for the mutation on phenotype.) A pedigree segregating for White has been generated and a candidate gene approach is employed by genotyping short tandem repeat loci (STRs), tightly linked to the strong candidate genes Pax3, Mitf, Slug, Ednrb, Edn3, Sox10, Kit, previously noted as causative of hypopigmentation and deafness in other mammalian species [21–30].

If significant linkage is not detected to a candidate gene, a whole genome scan will be performed using the newly available cat SNP chip [34]. The identified mutation will then be characterized in this extended colony and in a population genetic survey of cats (283 of registered breed, 19 mixed breed), including pigmented individuals and 34 unrelated Dominant White individuals to examine the correlation between the characterized mutation with white coat color and/or deafness [35].

White cats are neither necessarily deaf nor blue-eyed.

Examination of a large white deaf colony revealed a correlation between the likelihood that an individual will be deaf and/or blue-eyed based on their genotype (homozygous or heterozygous) at W inferred from designed breeding studies [36]. This correlation does not mean that the relationship is causal.

A potential explanation to the reduced penetrance at the feline W locus has been suggested. Melanocytes can be subdivided into cutaneous and noncutaneous lineages that respond differently to KIT signalling during development [37]. Cutaneous or “classical” murine melanocytes that “color” skin and hair are highly sensitive to KIT signalling, whereas melanocytes which populate the internal ear and portions of the eye (iris and choroid) are more effectively stimulated by endothelin 3 (EDN3) or hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) [37].

KIT has recently been implicated in two hypopigmentation phenotypes in the cat: White Spotting (S), in which significant linkage has been reported to KIT [38], and the glove gene [39]. The perceived lack of penetrance at W for deafness could be explained if KIT is identified as the feline White locus [37]. In individuals heterozygous for the mutation, some melanocytes could survive migration to the internal ear and iris as they are less sensitive to a decrease in KIT signalling, as opposed to melanocytes destined to pigment hair, which are highly sensitive to KIT signaling. The completion of linkage analysis may provide the answer to this question of penetrance.

Cochlear Anatomy and Physiology

Understanding mechanisms of deafness begins with a basic knowledge of the normal anatomy and physiology of the auditory pathway. Because the auditory system is complicated with many working parts, there are innumerable potential sources and locations where problems could arise. The first part of this review highlights structural and functional features of the peripheral and central auditory system. This background will provide a context with which to review the pathophysiology of hereditary and acquired deafness.

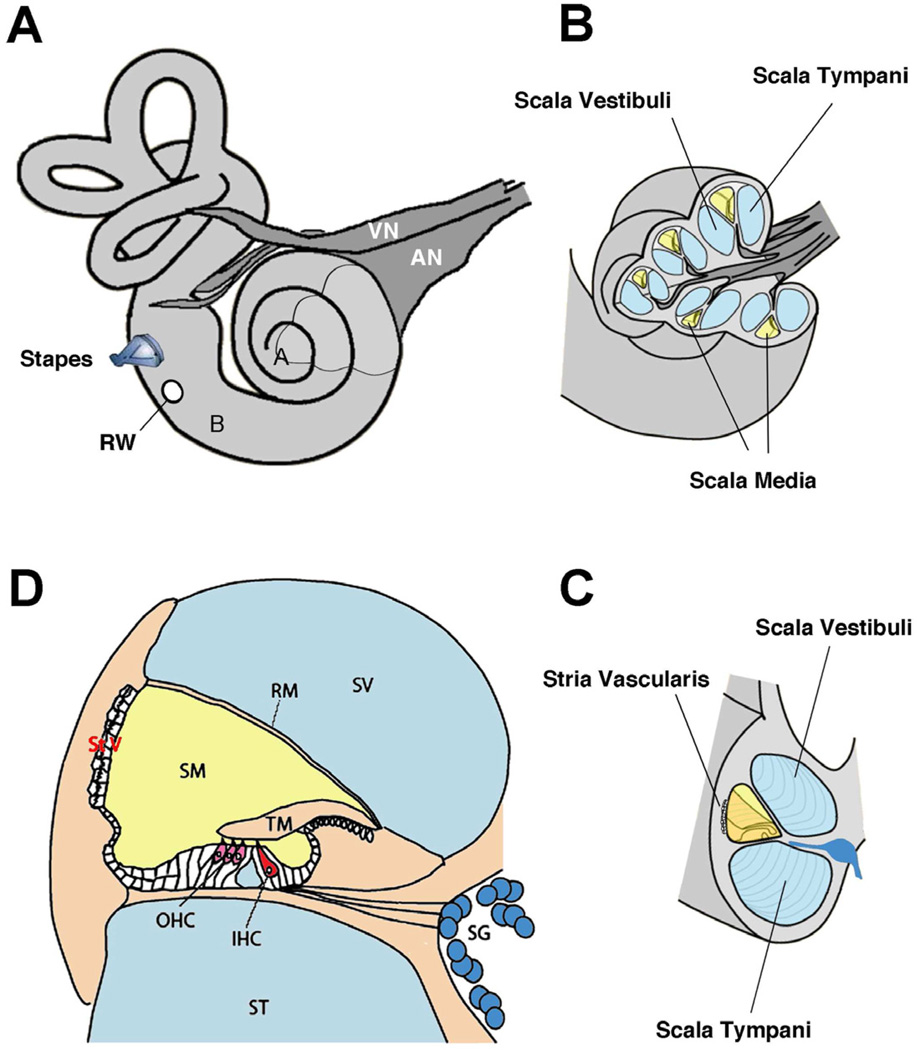

The cochlea is a spiraled bony tube housing three fluid-filled chambers that spiral along its length (Fig. 3). Highly specialized cells within the cochlea regulate the ionic composition of these chambers. One chamber is folded back at the apex to form two outer chambers (scala tympani and scala vestibuli) that sandwich a middle chamber (scala media). These outer chambers are confluent at the apex and contain perilymph, a filtrate of cerebrospinal fluid of similar composition to extracellular fluid (e.g., high sodium, low potassium). The middle chamber contains endolymph, a high-potassium, low-sodium fluid of similar composition to intracellular fluid. The outer wall of scala media is partially lined by the stria vascularis (Fig. 3). The stria is a vascularized, multilayered epithelial structure formed by three different cell types: marginal, intermediate, and basal cells (Fig. 4). A superficial layer of marginal cells borders the endolymph. Pale-staining basal cells are linked to each other, to intermediate cells, and to fibrocytes of the spiral ligament by gap junctions. This network provides cytoplasmic confluence that allows the free diffusion of K+ toward the marginal cells. Intermediate cells are marked by the presence of melanosomes and by deep infoldings of the plasma membrane that are matched by those of the overlying marginal cells. The resulting dense, labyrinthine membrane system of narrow compartments is filled with mitochondria and surround the penetrating capillaries that course longitudinally along the epithelium. The elaborate infoldings of membrane greatly amplify the cell surface in order to transfer K+ into marginal cells for secretion into the endolymph [40,41].

Figure 3.

Anatomy of the inner ear. (A) view of right hearing and balance apparatus. The cochlea is the coiled structure on the right and the semicircular canals of the vestibular system are on the left. For the cochlea, “A” indicates the apex (low frequencies) and “B” indicates the base (high frequencies). The stapes, a middle ear bone, inserts into the vestibule of the inner ear; the round window (RW) is covered by a membrane that relieves the pressure when the stapes “pistons” into the ear. The auditory (AN) and vestibular (VN) nerves bundle together to form the 8th cranial nerve. (B) A section of the otic capsule has been cut away (indicated in A) to reveal the three chambers of the labyrinth. The sensory organ resides in the scala media (yellow). (C) A rotated view of the cut end of a cochlear turn showing the three chambers, with the scala media (yellow) and the stria vascularis. (D) Enlarged diagram showing a cross-section through the scala media, emphasizing the organ of Corti and the hair cell receptors.

Abbreviations: IHC, inner hair cell; OHC, outer hair cells; RM, Reissner’s membrane; SG, spiral ganglion; SM, scala media; ST, scala tympani; StV, stria vascularis; SV, scala vestibuli; TM, tectorial membrane. Adapted from Fig. 1, Eisen and Ryugo, 2007. (Eisen MD, Ryugo DK, Hearing molecules: contributions from genetic deafness, Cell Mol Life Sci 2007; Mar 64(5): 566-80, with permission.)

Figure 4.

Schematic drawing of the stria vascularis. Movement of K+ ions through the gap junctions and then into the endolymph by way of ion pumps is crucial. This structure is the part of the inner ear that provides the special chemical environment that allows the system to function. (Courtesy of Dr. David K. Ryugo, Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Sydney, Australia.)

As a result of the differences in ionic composition between the compartments, the potential difference between endolymph and perilymph is about +80 mV. This positive potential is the largest found in the body. Since the intracellular resting potential of hair cell receptors is around −70 mV, the potential difference across the hair cell apex is a remarkable 150 mV. This large potential difference represents a tremendous ionic force and serves as the engine driving the mechanoelectrical transduction process of the hair cell [42]. Membrane specializations that feature gap junctions allow free passage of K+ ions through fibrocytes and basal cells and into intermediate cells. K+ channels and pumps transfer K+ from intermediate cells into the intrastrial fluid and then it gets concentrated in the marginal cells. K+ is driven into the endolymph down the K+ concentration gradient established in the marginal cells. The cycling of K+ through the receptor cells and back into the endolymph is key to normal cochlear function.

Gap junctions are channels that allow rapid transport of ions and small molecules between cells. In the stria vascularis, the ion is potassium (K+).

Connexins are transmembrane proteins that form gap junction channels. Four different connexin molecules have been identified in the cochlea, including connexin 26, 30, 31, and 43 [43].

Mutations that affect internal ear connexins result in hearing impairment and deafness.

Mutations that affect K+ transport result in hearing impairment and deafness.

Properties of the cochlea

Sound vibrations are eventually delivered to the stapes, whose footplate serves as a kind of piston and imparts vibrations to the fluids of the scala vestibuli. Specializations within the cochlea decompose the mechanical stimulus of sound into its frequency components. The basilar membrane is a fibrous sheet stretched across the floor of scala media. Its width and thickness vary systematically from the base to the apex of the cochlea in that there is a continuous elasticity gradient from one end to the other. The base is narrow and thick, whereas the apex is wide and thin. This structure functions like a frequency analyzer where it resonates to high frequencies at the base and to progressively lower frequencies along towards the apex.

The organ of Corti is the sensory organ for hearing.

- It is a multisensory structure that consists of the following:

- Basilar membrane

- Support cells

- Inner hair cells that are the primary sensory receptor

- Outer hair cells that modify the activity of the inner hair cells

- The tectorial membrane

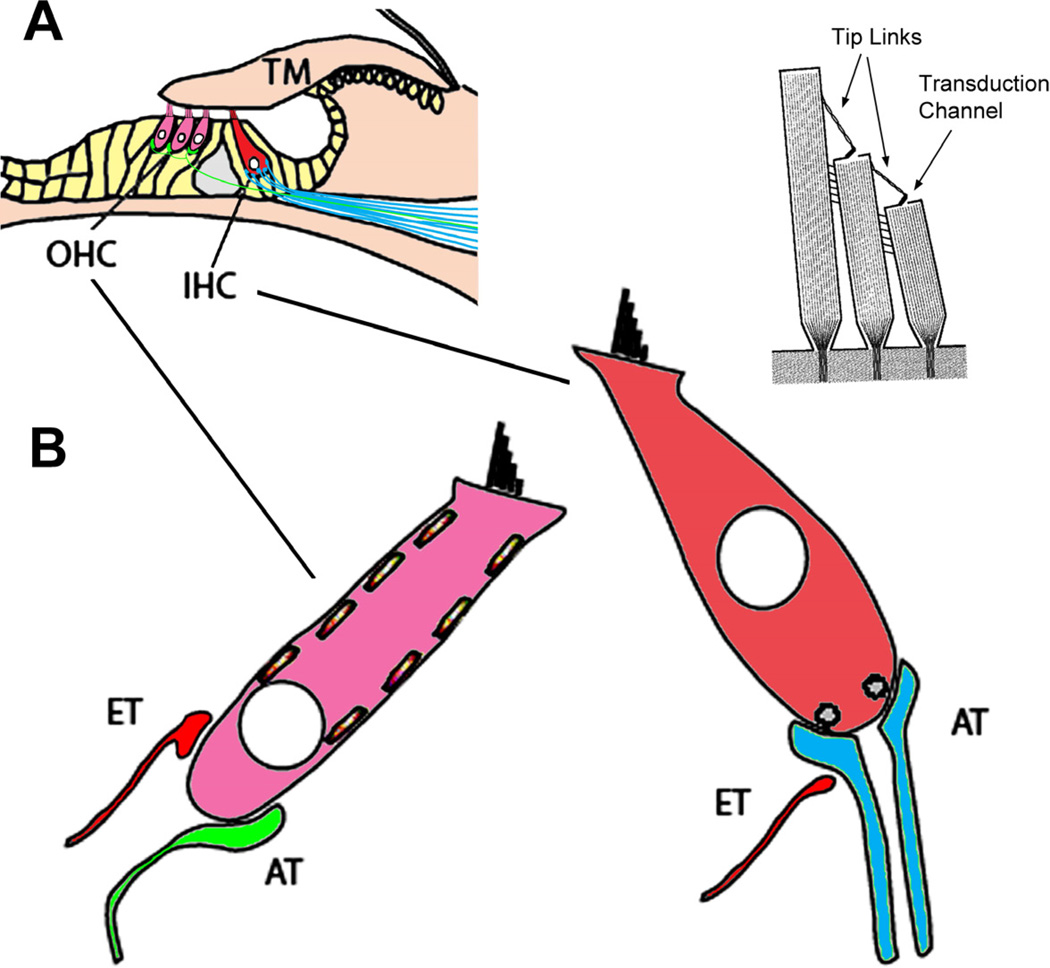

The organ of Corti rests on top of the basilar membrane (Fig. 5). Inner hair cells synapse onto afferent endings of the myelinated cochlear nerve fibers and are primarily responsible for conveying sensory information to the brain. In contrast, outer hair cells synapse on a small number of unmyelinated cochlear nerve fibers and receive large efferent nerve endings. The outer hair cells also contain contractile machinery that responds to membrane voltage changes. The outer hair cell’s function appears more involved with amplifying and manipulating the sound stimulus. Specialized supporting cells in the organ of Corti complement the hair cells and have a vital role in maintaining the integrity and function of the hair cells. A final component of the cochlea’s functional apparatus is the tectorial membrane, a gelatinous ribbon of extracellular matrix attached medially and contacting the outer hair cell hair bundles.

Figure 5.

Components of the organ of Corti. (A) The organ of Corti rests on the basilar membrane, and is composed of the sensory receptor cells (OHCs and IHCs), supporting cells (yellow) and the tectorial membrane (TM). (B) The hair cell receptors are innervated by afferent type I (blue) and type II (green) terminals as well as by efferent (ET, red) terminals whose cell bodies reside in the brain stem. At the apical ends of the receptor cells are stereocilia that form part of the transduction apparatus with tip-links and channels (upper right). Adapted from Fig. 1, Eisen and Ryugo, 2007. (Eisen MD, Ryugo DK, Hearing molecules: contributions from genetic deafness, Cell Mol Life Sci 2007; Mar 64(5): 566-80, with permission.)

Hair cell anatomy, function, and innervation

Hair cells are polarized in that a bundle of stereocilia protrude from one end of the cell, their apex, which are composed of actin filaments (Fig. 5), whereas afferent innervation occurs only at the opposite end, the base. Interconnecting links from the tip of a shorter stereocilia to the shaft of a longer neighbor, called “tip links”, attach to the mechanoelectric transduction channel [44,45]. Mechanical oscillations of the basilar membrane cause stereocilia within hair bundles to be displaced relative to each other. This displacement puts the tip links under tension and “pulls open” cation channels. Due to the high endocochlear potential, cations flow into the hair bundle and depolarize the hair cell membrane potential. Where the apical end of the cell transduces mechanical energy, the basal end releases neurotransmitter and activates afferent synapses.

The intracellular processes that respond to changes in membrane potential are distinctly different between the two types of auditory hair cells. Inner hair cells form afferent synapses where membrane voltage changes are converted to action potentials in myelinated cochlear nerve fibers; outer hair cells, however, contain electromotile elements within their cell membrane and generally serve as mechanical amplifiers of the sound stimuli for inner hair cells [46].

The pre-synaptic machinery of inner hair cells is geared to generate graded release of neurotransmitter along their basolateral surface. Voltage-dependent Ca++ channels are localized with neurotransmitter release sites that open in response to membrane depolarization, which in turn results in the release of neurotransmitter. The amount of transmitter release is modulated by the magnitude of the membrane voltage change. Neurotransmitter diffuses across the synaptic cleft and binds to postsynaptic receptors on afferent dendrites of cochlear nerve fibers. This process begins the generation and propagation of action potentials along the afferent fibers.

Outer hair cells contain a contractile apparatus that responds to membrane voltage changes with contractions or elongations of the cell proper. This mechanical response appears to be conformational changes in cytoskeletal proteins of the plasma membrane wall that serve to modulate the oscillations transmitted to the inner hair cells’ hair bundles. In addition to the electromotile apparatus within the outer hair cell, a system of efferent auditory feedback innervates the hair cells. Both systems work in concert to tune and amplify the sound source [46].

The spiral ganglion

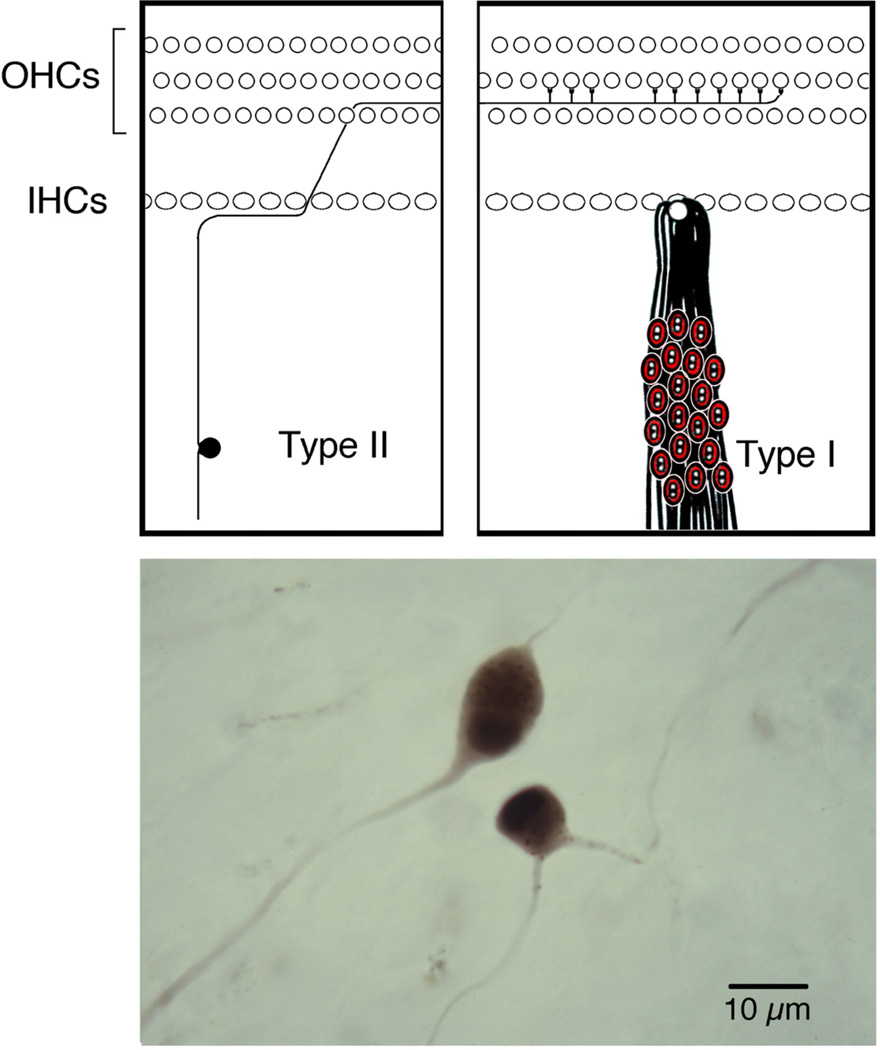

Spiral ganglion cells reside in Rosenthal’s canal of the cochlea (Fig. 6). Their peripheral processes innervate the hair cell receptors, and their central processes conduct auditory information to the brain. Two types of ganglion cells have been described [47,48].

Type I ganglion cells are large (20–30 µm in diameter), have myelinated processes, represent 90–95% of the population, and innervate inner hair cells.

Type II ganglion cells are small (15–20 µm in diameter), unmyelinated, represent the remainder of the ganglion population, and innervate exclusively outer hair cells.

Figure 6.

Receptor innervation by ganglion cells. (Top) drawing that illustrates the segregated innervation of hair cells by the two types of spiral ganglion cells. Type II neurons represent only 5–10% of the population and innervate multiple outer hair cells. In contrast, type I neurons represent the remaining 90–95% and innervate exclusively inner hair cells. Each IHC is innervated by 10–20 ganglion cells. (Bottom) photomicrograph of representative type I and type II ganglion cells as stained by horseradish peroxidase [100] (Kiang, NY-S, Morest, DK, Godfrey, DA, et al. Stimulus coding at caudal levels of the cat's auditory nervous system. I. Response characteristics of single units. In: Basic Mechanisms of Hearing. AR Moller, eds. New York: Academic Press; 1973. pp. 455–478.)

Cats have approximately 50,000 ganglion cells in each ear [49]. The central axons of the spiral ganglion cells collect within the central core of the cochlea, called the modiolus, and form the cochlear nerve. The cochlear nerve joins with the vestibular nerve to form the vestibulocochlear nerve, which together, along with the facial nerve, occupies the internal acoustic meatus within the petrous portion of the temporal bone. The vestibulocochlear nerve travels toward the brainstem where the cochlear branch enters and terminates within the cochlear nucleus, whereas the vestibular branch pass beneath and around the cochlear nucleus to arch up to the vestibular nuclei.

Effects of Deafness on the Auditory System

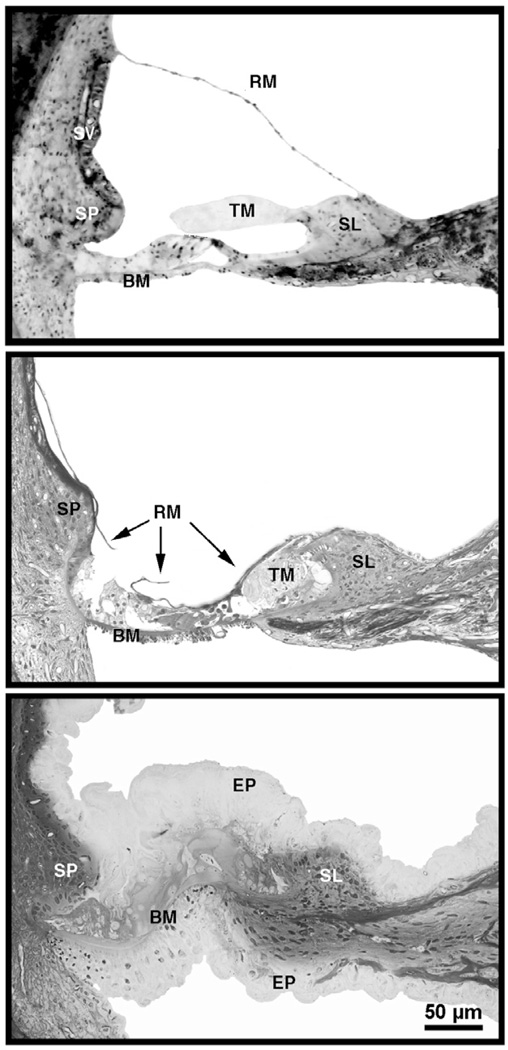

White cats with blue eyes are undoubtedly the best-known representatives of feline deafness. It has been extensively studied with a number of scholarly publications on the subject [5,6,36,50]. The most common cause of deafness in these cats is degeneration of the cochlea and saccule, termed cochleo-saccular degeneration (Fig. 7). This deafness mimics the Scheibe deformity of humans [5,51–53], which features early postnatal onset of sensorineural hearing impairment that is transmitted in an autosomal dominant pattern with incomplete penetrance [5,36,54–56].

Blue-eyed white cats can have what is called cochleosaccule degeneration, causing profound deafness.

White cats can also exhibit “spongioform” degeneration of the internal ear, also causing deafness.

White cats are not necessarily albino cats. White cats can exhibit varying amounts of melanin, whereas albino cats have no melanin. Some white cats are deaf; albino cats are not deaf.

Figure 7.

Photomicrographs of organ of Corti in cats with normal hearing (top), cats deafened by the collapse of Reissner’s membrane, thinning of the stria vascularis, and obliteration of the sensory epithelium (middle), and cats deafened by spongioform hypertrophy that destroys the organ of Corti (bottom) [65]. Scale bar equals 50 µm. Abbreviations: BM, basilar membrane; EP, epithelium; RM, Reissner’s membrane; SL, spiral limbus; SP, spiral prominence; SV, stria vascularis; TM, tectorial membrane. (from Ryugo, DK, Cahill, HB, Rose, LS, et al. Separate forms of pathology in the cochlea of congenitally deaf white cats. Hear. Res. 2003;181: 73–84, with permission.)

Deaf white cats show an absence of melanocytes [57], whereas albinos have a normal distribution of melanocytes but lack the enzyme tyrosinase and so are incapable of producing melanin pigment [58]. Although albino cats are not deaf they exhibit abnormal auditory evoked brainstem responses (ABR) at least when compared to pigmented cats [59]. Although ABR thresholds, peak shapes, and peak latencies can vary considerably from lab to lab [60–62], there is a distinct loss of sensitivity in albino cats. The underlying causes of these variations are unknown but definite atrophic changes in the auditory pathway occur as a result of pigment-related alterations of internal ear development [63].

The appearance of the internal ear of deaf cats is strikingly different from that of hearing cats. Cats were given hearing tests when they were 30 days postnatal. At this age, cats with normal hearing stabilize their pinna reflex, orient appropriately to sounds in space, and learn to differentiate between sounds [64]. Moreover, mesenchyme has cleared from the middle ear and the external ear canal is open to the tympanic membrane [65]. Deafness is indicated by a failure to elicit a sound evoked brain response and is coupled to cochlear pathology. Deafness in white cats has been correlated with two types of structural abnormalities. The more common form resembled that which has been previously reported [5,6,66,67] in which Reissner’s membrane is collapsed on the organ of Corti and the scala media is obliterated (middle panel, Fig. 7). The collapse occurs during the first ten postnatal days. The stria vascularis is present but is distinctly thinner than normal (compare top and middle panel, Fig. 7). By the time the external ear canal opens (after the third postnatal week), kittens that are completely unresponsive to acoustic stimulation have no scala media upon histological examination. In older deaf cats, the organ of Corti is virtually unrecognizable.

The other form of cochlear pathology in white cats featured a proliferation of cells throughout the cochlear spiral (bottom panel, Fig. 7). There was a hypertrophy of Reissner’s membrane such that it became highly irregular and folded, eventually filling the scala media [65]. The supporting cells of the organ of Corti and epithelial cells of the basilar membrane hypertrophied as well. The basilar membrane was buckled, the tunnel of Corti never attained its characteristic triangular shape, hair cells did not differentiate, and the stria vascularis was obscured. Overall, the tissue exhibited a “spongiform” appearance.

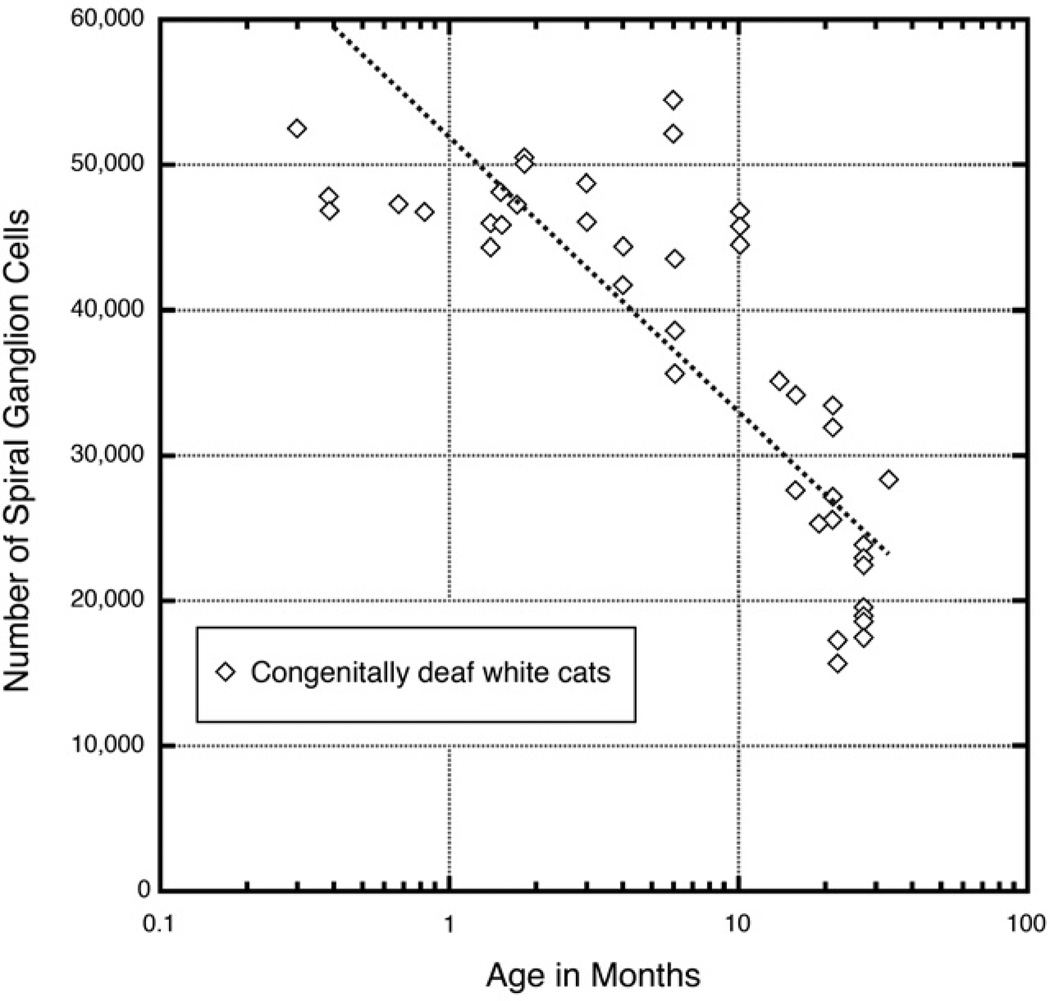

Spiral ganglion cells have their cell bodies in the peripheral auditory system, but extend their central terminations into the central auditory system. The survival of these ganglion neurons is dependent upon the health of the organ of Corti because they undergo degeneration that is associated with hair cell loss and sensorineural deafness [68–72]. In congenitally deaf white cats, there is a gradual loss of spiral ganglion cells with age with about half the population surviving after a year (Fig. 8). Several studies have addressed the effects of intracochlear electrical stimulation on spiral ganglion cell survival following neonatal deafness because of the importance these cells play in the outcome of cochlear implants. The actual benefits of electrical stimulation are still subject of debate because of conflicting outcomes [73–80].

Figure 8.

Plot of spiral ganglion cell loss over time as determined for congenitally deaf white cats. Data taken from [6, 49].

Trans-synaptic Changes in the Auditory Pathway: Cochlear Nucleus

Afferent activity is essential for the normal development and maintenance of the central auditory system in mammals. Reductions of cochlear nerve input to the brain have been produced by drugs, nerve section or cochlear ablation, and noise trauma. These measures produce dramatic changes in the structure and function of the central auditory pathway [81–90]. Are the pathologic changes due to the side effects of experimental manipulations, missing sensory receptors, absent cochlear nerve activity, or deafness regardless of cause? Does auditory enrichment have an opposing effect on brain structure and function as compared to auditory deprivation? In order to better understand the “nurture” component of brain development, we need to establish baseline features for the normal central auditory system as well as for the hearing impaired system.

Electrophysiological recordings from cochlear nerve fibers of pigmented cats with normal hearing provided standard tuning curves and thresholds [67]. These cats also exhibited normal startle and orientation responses to hand claps presented behind them. In contrast, deaf white cats exhibit no such behavioral responses, no sound-evoked spike activity, and greatly reduced spontaneous activity. The sampling of fibers was based upon intracellular penetration, so we did not bias our results by searching for the presence of “extracellular” action potentials. The sudden potential drop from 0 to −40 mV indicated that the recording tip of the electrode was “inside” an individual cochlear nerve fiber [91,92] so fibers with near zero spontaneous activity were not missed.

Activity and Structure

Roughly 60% of cochlear nerve fibers exhibit high levels of spontaneous spike discharges (40–100 spikes per second) in normal hearing cats. It is no wonder that neural activity exerts an influence on cellular morphology. Sensorineural hearing loss results in a loss of activity whose effect on target cell size in the cochlear nucleus can vary among the different cell types [93–95]. The cochlear nucleus is not a homogeneous structure. A number of different neuron populations have been described that are associated with different classes of cochlear nerve endings [96–99]. The idea has been suggested that the relationship between inputs and cell morphology defines the neuron’s response to sound [100,101]. What has emerged over the years is the notion that neuron classes can be defined by shared physiological response properties, morphologic characteristics, and synaptic inputs, and that they form different cell populations that have separate outputs to higher centers. These divergent circuits process different features of sound but converge again at a “central processor” to produce a percept of the auditory signal.

The timing and synchrony of this processing is crucial because continuity is what unifies sounds into a coherent stream. We will describe one circuit involved in acoustic “timing” to illustrate this idea. Brain changes caused by peripheral hearing loss must be mediated, at least in part, by cochlear nerve fibers and their interactions in the cochlear nucleus. Since the cochlear nucleus is the gateway to the central auditory system, any corruption of signal processing that occurs there will be felt at higher centers. The pathophysiology manifest at the cochlear nucleus will indicate where else in the auditory system defects might appear.

At the termination of the ascending branch of each cochlear nerve fiber is a prominent axosomatic terminal ending that is distinguished by its large size and complex arborization around the postsynaptic cell body (Fig. 9). This distinctive class of synaptic ending is called an endbulb [99,102,103]. Interestingly, in every land vertebrate examined, cochlear nerve fibers terminate in the cochlear nucleus with an endbulb [104]. The evolutionary conservation and large size emphasize its importance to auditory processing. The numerous synaptic release sites that embrace the cell body of a spherical bushy cell suggest a fail-safe transmission from nerve fiber to brain cell, exactly the relationship necessary to preserve timing in the auditory signal. Recall that the ability to localize the source of a sound depends on two ears: the ear closer to the source hears the sound sooner and louder than the far ear. The difference in time of arrival and loudness between the two ears provides the cues for sound localization. The endbulb and its postsynaptic neuron form the start of the brain circuit that encodes timing.

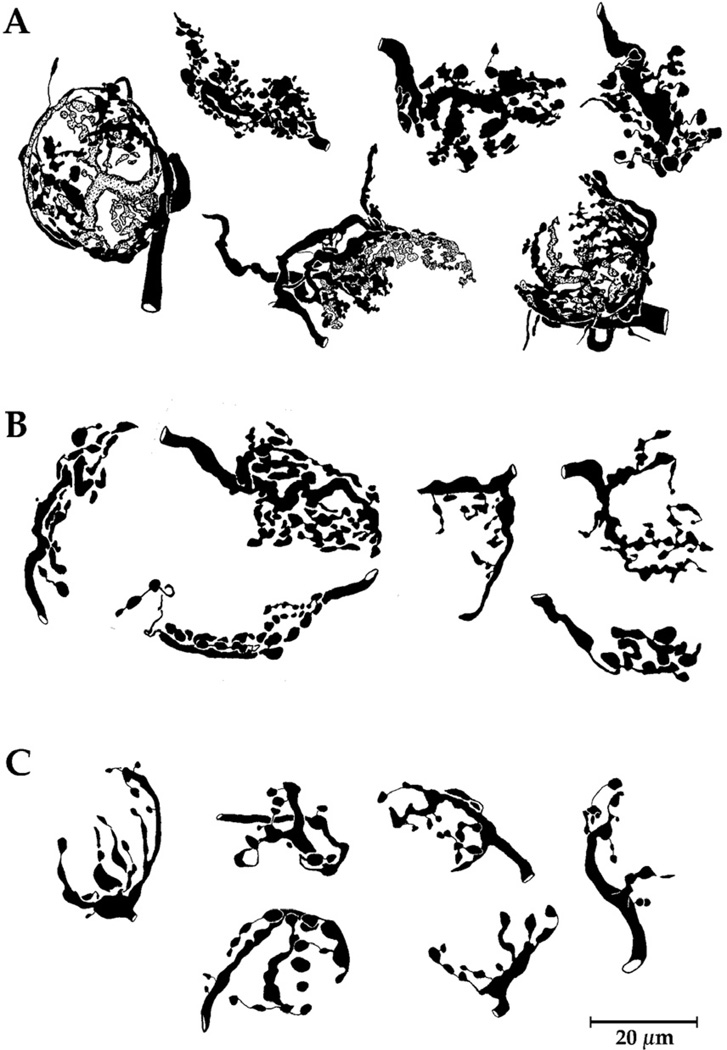

Figure 9.

Photomicrographs of typical endbulbs stained by horseradish peroxidase in the cochlear nucleus of the cat. Note their large size and elaborate branching pattern. A cell body is nestled within the grasp of the endbulb arborization. (Courtesy of Dr. David K. Ryugo, Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Sydney, Australia.).

It had been observed that endbulb morphology was distinctly related to the spontaneous discharge rate (SR) and threshold of the cochlear nerve fiber in normal hearing cats. Those endbulbs arising from fibers with low activity exhibit smaller but more highly complex arborizations in comparison to those fibers of high activity [105]. This activity-related difference in endbulb morphology is subtle and required fractal analysis to provide conclusive evidence of this variation. In the cats with hearing loss, analysis revealed endbulb size and branching complexity to be correlated with hearing sensitivity and fiber activity (Fig. 10).

Figure 10.

Camera lucida drawings of endbulbs from normal hearing cat (A), white cat with 50 dB hearing loss (B), and congenitally deaf white cat (C). Note that the complexity of the shape of endbulbs diminishes with hearing loss. Figure taken from Fig. 10 [67] (Ryugo, DK, Rosenbaum, BT, Kim, PJ, et al. Single unit recordings in the auditory nerve of congenitally deaf white cats: morphological correlates in the cochlea and cochlear nucleus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1998;397: 532–548, with permission.)

Endbulb synapses

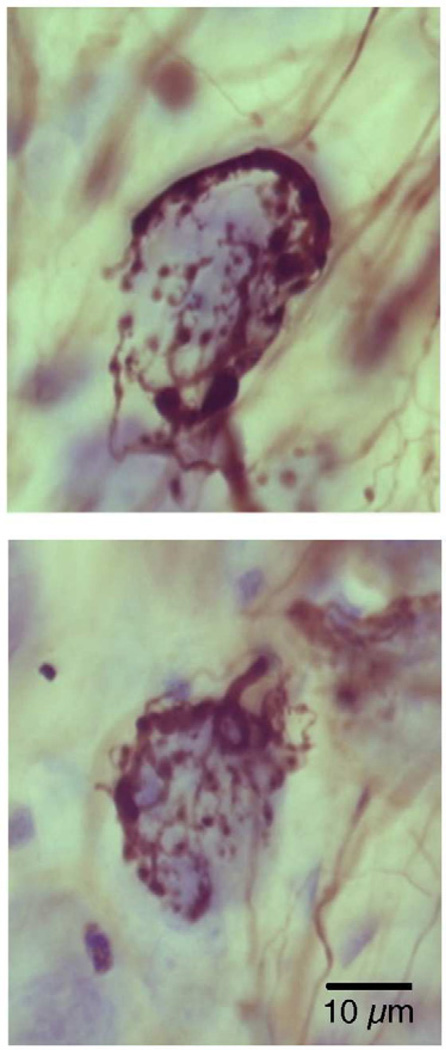

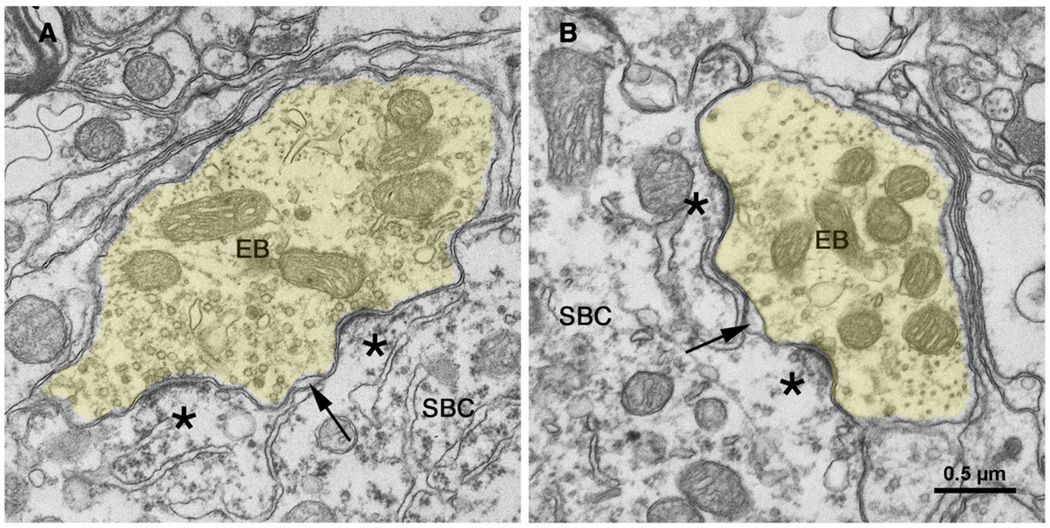

Differences in endbulb branching complexity were observed as a reflection of hearing status. Endbulb synapses were then examined with the aid of an electron microscope because synapses represent the crucial functional unit. Cochlear nerve synapses from normal hearing cats have been well described [106,107], so they will be only briefly mentioned for comparison purposes to those of the white cats. Transmitter release sites form around discrete postsynaptic densities, where the postsynaptic membrane bulges into the presynaptic endbulb to form a dome (Fig. 11). Clear, round synaptic vesicles are scattered throughout the endbulb cytoplasm but are concentrated around the release sites. A normal endbulb may have up to 2,000 individual presynaptic release sites [108], which oppose round-to-oval membrane thickenings called the postsynaptic density (PSD). These membrane specializations contain transmitter receptors and are distributed relatively uniformly beneath the overlying endbulb.

Figure 11.

Electron micrographs through synapses of endbulbs (EB) from cats with normal hearing [135]. The endbulb (yellow) forms synapses opposite dome-shaped postsynaptic densities (*) and round synaptic vesicles accumulate along the presynaptic membrane. Cisternae (arrow) form between the membrane of the endbulb and that of the postsynaptic spherical bushy cell (SBC); these intermembraneous channels may serve as “gutters” to facilitate transmitter diffusion away from the synapse. Scale bar equals 0.5 µm. [135] (O'Neil, JN, Limb, CJ, Baker, CA, et al. Bilateral effects of unilateral cochlear implantation in congenitally deaf cats. J. Comp. Neurol. 2010;518: 2382–2404, with permission.)

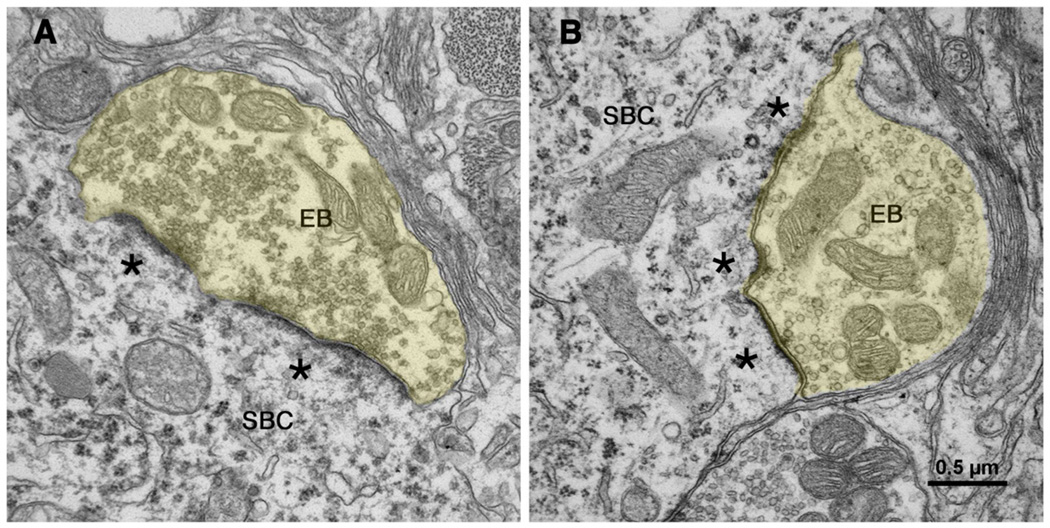

In contrast, synapses from totally deaf white cats appear distinctly different. Presynaptic vesicle density is distinctly increased and postsynaptic densities are thicker and considerably expanded (Fig. 12). Reconstructing the postsynaptic membrane, which lay beneath the presynaptic endbulb, demonstrated PSD hypertrophy by its expansion over the surface of the neuron. Synapses of partially deaf cats (e.g., those with elevated thresholds), however, seemed to represent a transition between normal and deaf synapses [67].

Figure 12.

Electron micrographs through synapses of endbulbs (EB) of congenitally deaf cats [135]. The postsynaptic densities of these synapses have hypertrophied (*) and become more flattened. Synaptic vesicles have proliferated in the endbulb (yellow) cytoplasm and intermembraneous channels have disappeared. The scale bar equals 0.5 µm. [135] (O'Neil, JN, Limb, CJ, Baker, CA, et al. Bilateral effects of unilateral cochlear implantation in congenitally deaf cats. J. Comp. Neurol. 2010;518: 2382–2404, with permission.)

Trans-synaptic Changes in the Auditory Pathway: Superior Olivary Complex

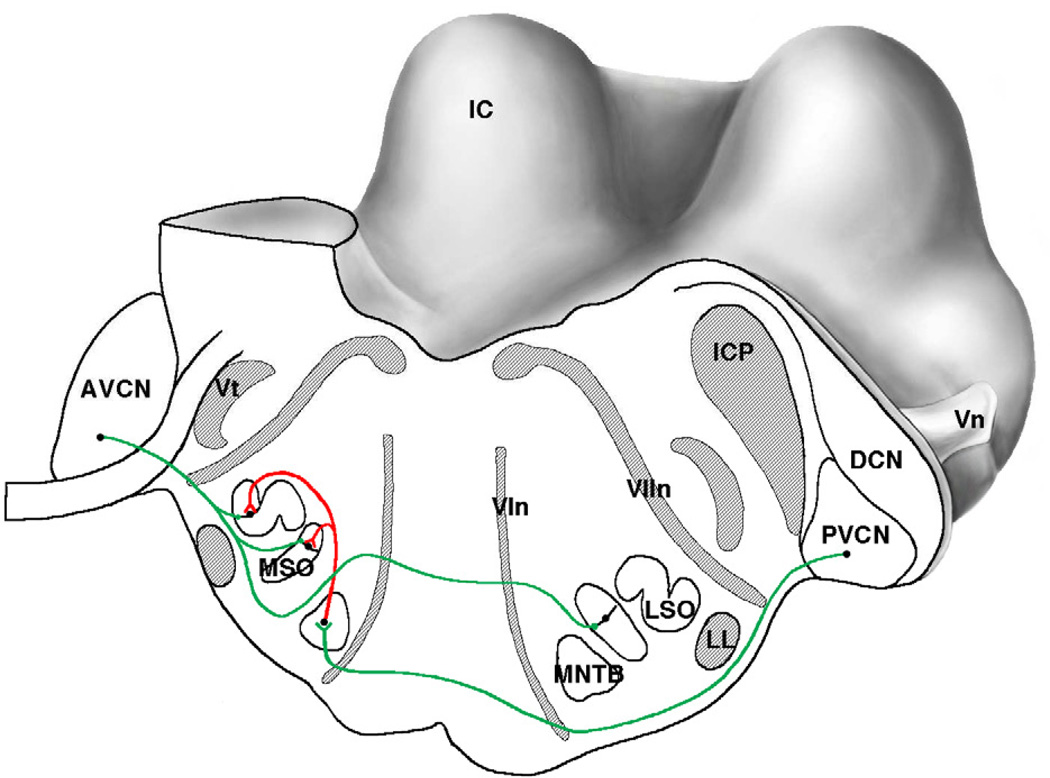

The medial superior olive (MSO) is the first site in the central auditory pathway where convergence of neural information from the two ears occurs (Fig. 13). The convergence arises from the cochlear nucleus neurons that are the recipients of endbulb synapses. The principal neurons of the MSO are aligned in a vertical sheet with its diametrically opposed bipolar dendrites facing medially and laterally [109]. Excitatory inputs are segregated such that ipsilateral input innervates lateral dendrites in the ipsilateral MSO and medial dendrites of the contralateral MSO [110,111]. These neurons have a proposed function as a “coincidence detector” for processing interaural timing differences (ITD) [112]. In addition, inhibitory input to the MSO arise from the medial (MNTB) and lateral nucleus of the trapezoid body (LNTB), are confined to the cell bodies of MSO neurons, and function to adjust the output signal of MSO neurons to higher centers [113,114].

Figure 13.

Caudal-lateral view of the cat brain stem where the cut surface passes through the superior olivary complex. The cut is angled so that it also passes through different parts of the cochlear nucleus on the left and right. The excitatory path from the spherical bushy cells of the left anteroventral cochlear nucleus (AVCN) initiates processing of interaural timing differences in the medial superior olive (MSO) and interaural level differences in the lateral superior olive (LSO). The excitatory path from globular bushy cells of the right posteroventral cochlear nucleus (PVCN) initiates the processing of interaural level differences, and its target is the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB). The output of the MNTB is inhibitory (red) and it terminates in the MSO and LSO. Abbreviations: AVCN, anteroventral cochlear nucleus; DCN, dorsal cochlear nucleus; IC, inferior colliculus; ICP, inferior cerebellar peduncle; LL, lateral lemniscus; LSO, lateral superior olive; MNTB, medial nucleus of the trapezoid body; MSO, medial superior olive; VIn, abducens (6th) nerve root; VIIn, facial (7th) nerve root; Vn, trigeminal (5th) cranial nerve; Vt, spinal trigeminal tract. (Drawn by Catherine Connelly, Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Sydney, Australia.)

Congenital deafness causes a bilateral disruption in the spatially segregated inputs to the MSO principal neurons such that inhibitory input at the cell body is significantly reduced compared to what is observed in hearing animals [90,111]. This change in axosomatic inhibition was manifest by a loss of staining for gephyrin, an anchoring protein for the glycine receptor [111] and the migration of terminals containing flattened and pleomorphic synaptic vesicles (indicative of inhibitory synapses) away from the cell body [90]. Excitatory inputs to the dendrites were severely shrunken [90] and the dendrites themselves atrophied [115].

Trans-synaptic Changes in the Auditory Pathway: Inferior Colliculus

The inferior colliculus (IC) is a complex, tonotopically organized nucleus of the midbrain receiving auditory inputs from many ascending brainstem sources including both cochlear nuclei, superior olivary complex, and nuclei of the lateral lemniscus as well as descending inputs from the auditory cortex and superior colliculus [116–118]. It is a large bilateral nucleus. A rudimentary tonotopic organization within the IC has been shown to exist in long-term deafened animals [119,120]. This organization is evident even in congenitally deaf animals, implying that a blueprint for connections is in place and can develop even without the benefit of hearing [121].

Acute deafness did not increase temporal dispersion in spike timing to trains of electric pulse stimulation in the cochlear nerve nor impair ITD sensitivity [122,123]. Congenital deafness, however, did reduce ITD sensitivity in the responses of IC units. Single cell recordings in the IC showed that half as many neurons in the congenitally deaf cat showed ITD sensitivity to electrical stimulation when compared to the acutely deafened animals. In neurons that showed ITD tuning, they were found to be broad and variable [124]. The synaptic changes that disrupt the electrophysiological response properties are a reflection of neuronal response profiles that arise from lower structures in the pathway [125–128]. Collectively, the data imply that ITD discrimination is a highly demanding process and that even with near perfect synapse restoration, the task is sufficiently difficult that perhaps only complete restoration of synapses will enable the full return of function.

Trans-synaptic Changes in the Auditory Pathway: Auditory Cortex

The endpoint of stimulus coding along the auditory pathway presumably occurs in the auditory areas of the cerebral cortex. Acoustic features such as distance, location, pitch, motion, and significance are carried by the auditory stream and become unified into a single percept. This unity is coordinated by a system of multiple auditory areas that are fed by the parallel sets of ascending pathways. Hierarchically processed acoustic events are distributed across the different cortical areas and assembled for cognitive interpretation (Fig. 14). The number and complexity of cortical areas is testament to the computational demands on hearing [129]. Not surprisingly, congenital deafness leads to functional and morphological abnormalities along the auditory pathway including auditory cortex [130,131]. The repair of these defects, fortunately, can be achieved through the timely restoration of normal activity in the auditory system [132–134].

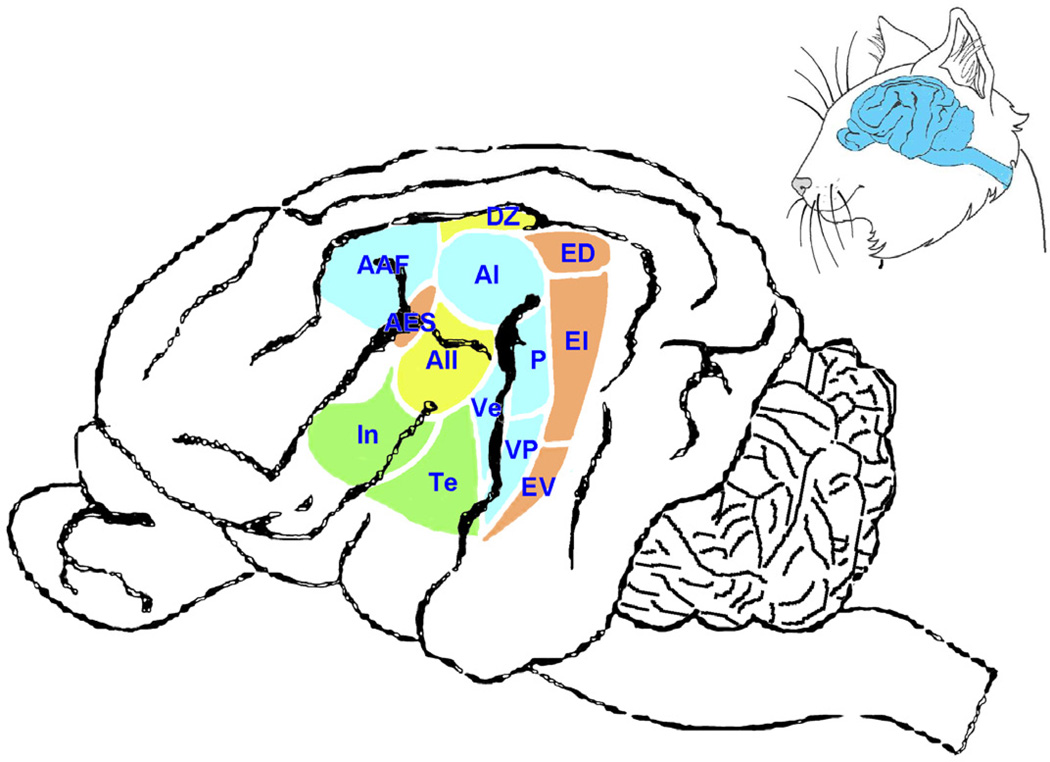

Figure 14.

Drawing of side view of cat brain. The inset (upper right) illustrates the position of the brain relative to the head. The gyral patterns of the cortex are fairly reproducible across individual cats but they are not identical; thus, they are not reliable markers for cortical function. The many auditory areas reflect the complex processing involved in creating sound awareness. Nomenclature adopted from [129]. Abbreviations: AAF, anterior auditory field; AES, anterior ectosylvian sulcus area; AI, primary auditory cortex; AII, secondary auditory cortex; DZ, dorsal auditory zone; ED, posterior ectosylvian gyrus; EI, posterior ectosylvian gyrus, intermediate part; EV, posterior ectosylvian gyrus, ventral part; In, insular cortex; P, auditory cortex, posterior area; Te, temporal cortex; Ve, auditory cortex, ventral area; VP, auditory cortex, ventral posterior area. (Courtesy of David K. Ryugo, Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Sydney, Australia.)

Conclusion

In summary, hearing is a vital sense in the everyday life of cats. It enables them to be constantly aware of their environment especially when vision is insufficient. Hearing loss represents a huge disadvantage to them, and there are many possible sources of this disability. Deafness can be a result of genetic mutation, disease, industrial noise, ototoxic chemicals, or trauma. Any of these sources could cause abnormalities in sensory transduction in the ear that lead to brain pathology in structure, chemistry, synaptic transmission, or perceptual dysfunction due to fouled circuits. Regardless of the cause, sensorineural deafness produces change in many parts of the nervous system that in general, cannot be treated, but contribute to the pathology.

Key Points.

Cats have among the best hearing of all mammals in that they are very sensitive to a broad range of frequencies. The rattle of the cat’s food box or the hiss of a can opening should be sufficient to summon your cat no matter where it is in the house. Failure to call your cat this way is a sign that it is ill or losing its hearing.

The ear is a highly complex structure that is delicately balanced in terms of its biochemistry, types of receptors, ion channels, mechanical properties, and cellular organization. Minor perturbations of any component of hearing can cause loss of function.

Sensorineural deafness is usually caused by “flawed” genes that are inherited from one or both parents. Defects can appear as a disturbance in chemistry, failure of the receptive sensory elements, or impaired biomechanics. Hearing loss can also be acquired as a result of noise trauma from industrialized environment, viral infection, or blunt trauma. To date, it is not practical to intervene and attempt to correct these forms of deafness.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the published data of their colleagues that made this review possible, and to Karen Henoch-Ryugo and Bradley L. Njaa for editorial comments on earlier drafts. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services or the National Health and Medical Research Council, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. or Australian Governments.

1DKR is supported by NHMRC grant #1009842, The Garnett Passe and Rodney Williams Memorial Foundation, NSW Office of Science and Medical Research, the Curran Foundation, and NIH/NIDCD grant DC004395; 2MMR is supported with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract HHSN26120080001E.

Glossary

- ABR

ABR is the acronym for a sound-evoked auditory brainstem response. It is a noninvasive means of assessing auditory responses of the brain as recorded from the scalp. Because of the relatively large distance from recording site to brain, the response must be averaged over 500–1000 stimulus presentations.

- Action potential, membrane potential

Action potential refers to a rapid change in electrical potential that is measured between the inside and outside of a nerve or muscle cell when stimulated. It is the common unit of communication between nerve cells.

- Afferent

Afferent is a term used to describe individual neurons, systems of neurons, or parts of neurons that convey information toward another neuron or into the central nervous system.

- Arborization

Arborization is a term used to describe a “treelike” appearance of certain neuron outgrowths, either an axon or its termination or the shape of dendritic branching.

- Autosomal dominant locus

Autosome refers to any chromosome that is not a sex-determining chromosome (e.g., not X and not Y). Two copies of every gene are located on a chromosome and tend to work together; when one gene overpowers the other, it is said to be dominant. The locus refers to the gene’s specific location on an identified chromosome.

- Axosomatic

Axosomatic refers to the relationship between an incoming synaptic terminal and the postsynaptic target, where “axo” refers to the incoming presynaptic structure and “somatic” indicates the postsynaptic cell body or soma. In this case, the axon terminal forms a synapse on the cell body of the target neuron. Axodendritic describes the case where an incoming axon terminal synapses on the dendrite. And so on.

- Candidate gene approach

The candidate gene approach focuses on associations between genetic variation within specified genes of interest and phenotypic expression of disease state or trait.

- Central auditory system

The central auditory system is that part of the hearing system that resides within the brain. It is composed of many neuronal structures that are linked together by axonal pathways to form an integrated system. Its normal function is to convert the physical attributes of sound into conscious perceptions of auditory meaning.

- Cochleosaccule dysplasia

Cochleosaccule dysplasia is pathology of the saccule (vestibular sensory organ) and cochlea (hearing organ). The dysplasia is characterized by a collapse of the saccular membrane and Reissner’s membrane, respectively, onto the sensory epithelium.

- Efferent

Efferent is the term used to describe individual neurons, systems of neurons, or parts of neurons that convey information away from its origin, as away from the cell body or away from the central nervous system.

- Endolymph, endolymphatic space, endocochlear potential

Endolymph is the specialized fluid of the inner ear that bathes the organ of Corti. It is contained within the endolymphatic space, which is equivalent to the cochlear duct. Its special high potassium content endows it with a positive potential (approximately +80 mV) relative to ground and the potential is called the endocochlear potential.

- Gap junctions

Gap junctions are membrane specializations between two cells that allow electrical coupling and the passage of ions and small molecules. These specializations underlie electrical synapses.

- Gloving

The gloving gene is implicated in the white feet of pigmented cats.

- Interaural time disparity

Interaural time disparity refers to the circumstance where a sound located away from the listener’s midline arrives at the closer ear before it arrives at the further ear. The difference in time of arrival is computed by the brain to inform the organism where along the horizontal plane, with respect to the head, the sound originated.

- KIT

Kit is a gene that is involved in the production of melanocytes, blood cells, mast cells, and stem cells. Mutations of this gene are known to cause white coat color.

- Knockouts

Knockouts or gene knockouts refer to a genetically engineered mouse where a gene has been inactivated or deleted (“knocked out”).

- Linkage

Linkage is the tendency of genes that are located near each other on a chromosome to be inherited together. The probability of such an occurrence is calculated by testing if the two loci are linked compared to observing the same traits purely by chance.

- Melanocytes

Melanocytes are neural-crest-derived, melanin-producing cells found mainly in the epidermis but also in eyes, ears, and meninges.

- Mesenchyme

Mesenchyme refers to cells of mesodermal origin that are capable of developing into connective tissue, blood, or endothelial tissue.

- Myelinated

Myelin is an insulating sheath around individual axons formed by the tight wrapping of cell membrane of oligodendrocytes in the central nervous system and Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system.

- Peripheral auditory system

The peripheral auditory system is that part of the hearing apparatus that resides in the cochlea (or inner ear).

- Pitch

Pitch is related to the frequency of sound vibrations and is an attribute of auditory sensation whereby sounds may be ordered from low to high.

- Pleiotropic effects

Pleiotropic refers to having multiple effects from a single gene.

- Pleomorphic synaptic vesicles

Pleomorphic synaptic vesicles is the term used to describe the circumstance where synaptic vesicles in aldehyde-preserved tissue, when examined with an electron microscope, exhibit a variety of shapes from round to oval to flattened. This variety of vesicle shapes is inferred to indicate inhibitory action at the associated synapse.

- Potential difference

Potential difference refers to the voltage difference between two points. In the case of endolymph and perilymph, it reflects the differential distribution of Na+, K+, and Cl− within two closed compartments.

- Receptor cell

Receptor cells are specialized to convert energy in the form of light, chemical, or mechanical into neural signals.

- Spongiform

Spongiform is an adjective used to describe the sponge-like appearance of a pathologic overgrowth of cells in the cochlea.

- Spontaneous discharge rate

Spontaneous discharge rate refers to the situation where a neuron gives rise to action potentials in the absence of experimenter-delivered stimulation.

- Stereocilia

Stereocilia are specialized microvilli that form on the top surface of auditory and vestibular sensory receptor cells. Deformation of the stereocilia in one direction opens ion channels, whereas deformation in the opposite direction closes them.

- Synapse

The synapse is a structure at the point of communication between two neurons where chemical or electrical signals can be passed.

- Syndromic deafness, nonsyndromic deafness

Syndromic deafness refers to hearing loss that is associated with other distinctive medical conditions; nonsyndromic deafness occurs by itself.

- Tonotopic

Tonotopic is a term used to describe the systematic organization of frequency across an auditory structure, where there is a progression of frequency representation from low to high.

- W

The primary gene responsible for white color. It is dominant over other colors, so white cats can be either Ww or WW. Cats that are ww express pigmentation patterns determined by other genes.

- Waardenburg syndrome

Waardenburg syndrome is a group of inherited conditions passed down through families that involve deafness and pale skin, hair and eye color.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Liberman MC. Auditory-nerve response from cats raised in a low-noise chamber. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1978;63:442–455. doi: 10.1121/1.381736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pickles JO. An Introduction to the Physiology of Hearing. U.K.: Emerald; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darwin C. The Origin of Species: 150th Anniversary Edition. New York: New American Library; 1859. republished in 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tait L. Note on deafness in white cats. Nature. 1883;29:164. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosher S, Hallpike C. Observations on the histological features, development and pathogenesis of the inner ear degeneration of the deaf white cat. Proc. Roy. Soc. B. 1965;162:147–170. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1965.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mair IW. Hereditary deafness in the white cat. Acta. Otolaryngol. (Suppl) 1973;314:1–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chabot B, Stephenson DA, Chapman VM, et al. The proto-oncogene c-kit encoding a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor maps to the mouse W locus. Nature. 1988;335:88–89. doi: 10.1038/335088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark LA, Wahl JM, Rees CA, et al. Retrotransposon insertion in SILV is responsible for merle patterning of the domestic dog. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:1376–1381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506940103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flottorp G, Foss I. Development of hearing in hereditarily deaf white mink (Hedlund) and normal mink (standard) and the subsequent deterioration of the auditory response in Hedlund mink. Acta Otolaryngol. 1979;87:16–27. doi: 10.3109/00016487909126383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gauly M, Vaughan J, Hogreve SK, et al. Brainstem auditory-evoked potential assessment of auditory function and congenital deafness in llamas (Lama glama) and alpacas (L. pacos) J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2005;19:756–760. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2005)19[756:bapaoa]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haase B, Brooks SA, Schlumbaum A, et al. Allelic heterogeneity at the equine KIT locus in dominant white (W) horses. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haase B, Brooks SA, Tozaki T, et al. Seven novel KIT mutations in horses with white coat colour phenotypes. Anim. Genet. 2009;40:623–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2009.01893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hilding DA, Sugiura A, Nakai Y. Deaf white mink: electron microscopic study of the inner ear. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1967;76:647–663. doi: 10.1177/000348946707600310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hodgkinson CA, Nakayama A, Li H, et al. Mutation at the anophthalmic white locus in Syrian hamsters: haploinsufficiency in the Mitf gene mimics human Waardenburg syndrome type 2. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998;7:703–708. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.4.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hudson W, Ruben R. Hereditary deafness in the dalmation dog. Arch. Otolaryngol. 1962;75:213–219. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1962.00740040221007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karlsson EK, Baranowska I, Wade CM, et al. Efficient mapping of mendelian traits in dogs through genome-wide association. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1321–1328. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magdesian KG, Williams DC, Aleman M, et al. Evaluation of deafness in American Paint Horses by phenotype, brainstem auditory-evoked responses, and endothelin receptor B genotype. J. Am. Vet.Med. Assoc. 2009;235:1204–1211. doi: 10.2460/javma.235.10.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruan HB, Zhang N, Gao X. Identification of a novel point mutation of mouse proto-oncogene c-kit through N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea mutagenesis. Genetics. 2005;169:819–831. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.027177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsujimura T, Hirota S, Nomura S, et al. Characterization of Ws mutant allele of rats: a 12-base deletion in tyrosine kinase domain of c-kit gene. Blood. 1991;78:1942–1946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silvers WK. The Coat Colors of Mice: a Model for Mammalian Gene Action and Interaction. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epstein DJ, Vekemans M, Gros P. Splotch (Sp2H), a mutation affecting development of the mouse neural tube, shows a deletion within the paired homeodomain of Pax-3. Cell. 1991;67:767–774. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tachibana M, Hara Y, Vyas D, et al. Cochlear disorder associated with melanocyte anomaly in mice with a transgenic insertional mutation. Mo.l Cell. Neurosci. 1992;3:433–445. doi: 10.1016/1044-7431(92)90055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hodgkinson CA, Moore KJ, Nakayama A, et al. Mutations at the mouse microphthalmia locus are associated with defects in a gene encoding a novel basic-helix-loop-helix-zipper protein. Cell. 1993;74:395–404. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90429-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baynash AG, Hosoda K, Giaid A, et al. Interaction of endothelin-3 with endothelin-B receptor is essential for development of epidermal melanocytes and enteric neurons. Cell. 1994;79:1277–1285. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tachibana M, Perez-Jurado LA, Nakayama A, et al. Cloning of MITF, the human homolog of the mouse microphthalmia gene and assignment to chromosome 3p14.1-p12.3. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1994;3:553–557. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.4.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Attie T, Till M, Pelet A, et al. Mutation of the endothelin-receptor B gene in Waardenburg-Hirschsprung disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1995;4:2407–2409. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.12.2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Southard-Smith EM, Kos L, Pavan WJ. Sox10 mutation disrupts neural crest development in Dom Hirschsprung mouse model. Nat. Genet. 1998;18:60–64. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Syrris P, Carter ND, Patton MA. Novel nonsense mutation of the endothelin-B receptor gene in a family with Waardenburg-Hirschsprung disease. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1999;87:69–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herbarth B, Pingault V, Bondurand N, et al. Mutation of the Sry-related Sox10 gene in Dominant megacolon, a mouse model for human Hirschsprung disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:5161–5165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanchez-Martin M, Rodriguez-Garcia A, Perez-Losada J, et al. SLUG (SNAI2) deletions in patients with Waardenburg disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:3231–3236. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.25.3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tasaki I, Spyropoulos CS. Stria vascularis as source of endocochlear potential. J. Neurophysiol. 1959;22:149–155. doi: 10.1152/jn.1959.22.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marcus DC, Wu T, Wangemann P, et al. KCNJ10 (Kir4.1) potassium channel knockout abolishes endocochlear potential. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C403–C407. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00312.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geigy CA, Heid S, Steffen F, et al. Does a pleiotropic gene explain deafness and blue irises in white cats? Vet. J. 2007;173:548–553. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2006.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mullikin JC, Hansen NF, Shen L, et al. Light whole genome sequence for SNP discovery across domestic cat breeds. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:406. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Menotti-Raymond M, David VA, Pflueger S, et al. Widespread retinal degenerative disease mutation (rdAc) discovered among a large number of popular cat breeds. Vet. J. 2010;186:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bergsma D, Brown K. White fur, blue eyes, and deafness in the domestic cat. J. Hered. 1971;62:171–185. doi: 10.1093/jhered/62.3.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aoki H, Yamada Y, Hara A, et al. Two distinct types of mouse melanocyte: differential signaling requirement for the maintenance of non-cutaneous and dermal versus epidermal melanocytes. Development. 2009;136:2511–2521. doi: 10.1242/dev.037168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooper MP, Fretwell N, Bailey SJ, et al. White spotting in the domestic cat (Felis catus) maps near KIT on feline chromosome B1. Anim. Genet. 2006;37:163–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2005.01389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lyons LA. Feline genetics: clinical applications and genetic testing. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 2010;25:203–212. doi: 10.1053/j.tcam.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dallos P. Overview: cochlear neurobiology. In: Dallos P, Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. The Cochlea. New York: Springer; 1996. pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wangemann P. K+ cycling and the endocochlear potential. Hear. Res. 2002;165:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wangemann P, Schacht J. Homeostasic mechanisms in the cochlea. In: Dallos P, Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. The Cochlea. New York: Springer; 1996. pp. 130–185. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cohen-Salmon M, Regnault B, Cayet N, et al. Connexin30 deficiency causes instrastrial fluid-blood barrier disruption within the cochlear stria vascularis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:6229–6234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605108104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rhys Evans PH, Comis SD, Osborne MP, et al. Cross-links between stereocilia in the human organ of Corti. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1985;99:11–19. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100096237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pickles JO, Comis SD, Osborne MP. Cross-links between stereocilia in the guinea pig organ of Corti, and their possible relation to sensory transduction. Hear. Res. 1984;15:103–112. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(84)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dallos P. The active cochlea. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:4575–4585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-12-04575.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spoendlin H. The innervation of the cochlea receptor. In: Moller AR, editor. Mechanisms in Hearing. New York: Academic Press; 1973. pp. 185–229. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kiang NY, Rho JM, Northrop CC, et al. Hair-cell innervation by spiral ganglion cells in adult cats. 1982;217:175–177. doi: 10.1126/science.7089553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen I, Limb CJ, Ryugo DK. The effect of cochlear implant-mediated electrical stimulation on spiral ganglion cells in congenitally deaf white cats. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2010;11:587–603. doi: 10.1007/s10162-010-0234-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strain GM. Deafness in Dogs and Cats. Wallingford: CABI; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deol MS. The relationship between abnormalities of pigmentation and of the inner ear. Proc. Royal Soc. Lond. 1970;175:201–217. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1970.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suga F, Hattler KW. Physiological and histopathological correlates of hereditary deafness in animals. Laryngoscope. 1970;80:81–104. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197001000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brighton P, Ramesar R, Winship I. Hearing impairment and pigmentary disturbance. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1991;630:152–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb19584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rawitz B. Gehörorgan und gehirn eines weissen Hundes mit blauen Augen. Morphol. Arbeit. 1896;6:545–554. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wolff D. Three generations of deaf white cats. J. Hered. 1942;33:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bosher SK, Hallpike CS. Observations on the histogenesis of the inner ear degeneration of the deaf white cat and its possible relationship to the aetiology of certain unexplained varieties of human congenital deafness. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1966;80:222–235. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100065191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Billingham RE, Silvers WK. The melanocytes of mammals. Quart. Rev. Biol. 1960;35:1–40. doi: 10.1086/402951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Imes DL, Geary LA, Grahn RA, et al. Albinism in the domestic cat (Felis catus) is associated with a tyrosinase (TYR) mutation. Anim. Genet. 2006;37:175–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2005.01409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Creel D, Conlee JW, Parks TN. Auditory brainstem anomalies in albino cats. I. Evoked potential studies. Brain Res. 1983;260:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90758-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Buchwald JS, Huang C-M. Far-Field acoustic response: Origins in the cat. Science. 1975;189:382–384. doi: 10.1126/science.1145206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Berry H, Blair RL, Bilbao J, et al. Click evoked eighth nerve and brain stem responses (electrocochleogram)--experimental observations in the cat. J. Otolaryngol. 1976;5:64–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Achor LJ, Starr A. Auditory brain stem responses in the cat. I. Intracranial and extracranial recordings. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1980;48:154–173. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(80)90301-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Conlee JW, Parks TN, Romero C, et al. Auditory brainstem anomalies in albino cats: II. Neuronal atrophy in the superior olive. J. Comp. Neurol. 1984;225:141–148. doi: 10.1002/cne.902250115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Villablanca JR, Olmstead CE. Neurological development in kittens. Dev. Psychobiol. 1979;12:101–127. doi: 10.1002/dev.420120204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ryugo DK, Cahill HB, Rose LS, et al. Separate forms of pathology in the cochlea of congenitally deaf white cats. Hear. Res. 2003;181:73–84. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00171-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rebillard M, Pujol R, Rebillard G. Variability of the hereditary deafness in the white cat. II. Histology. Hear. Res. 1981b;5:189–200. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(81)90045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ryugo DK, Rosenbaum BT, Kim PJ, et al. Single unit recordings in the auditory nerve of congenitally deaf white cats: morphological correlates in the cochlea and cochlear nucleus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1998;397:532–548. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980810)397:4<532::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Webster M, Webster DB. Spiral ganglion neuron loss following organ of Corti loss: a quantitative study. Brain Res. 1981;212:17–30. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Spoendlin H. Factors inducing retrograde degeneration of the cochlear nerve. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1984;112(Suppl):76–82. doi: 10.1177/00034894840930s415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Leake PA, Hradek GT. Cochlear pathology of long term neomycin induced deafness in cats. Hear. Res. 1988;33:11–34. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(88)90018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hardie NA, Shepherd RK. Sensorineural hearing loss during development: morphological and physiological response of the cochlea and auditory brainstem. Hear. Res. 1999;128:147–165. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shepherd RK, Meltzer NE, Fallon JB, et al. Consequences of deafness and electrical stimulation on the peripheral and central auditory system. In: Waltzman SB, Roland JT, editors. Cochlear Implants. New York: Thieme Medical PUblishers Inc.; 2006. pp. 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lousteau RJ. Increased spiral ganglion cell survival in electrically stimulated, deafened guinea pig cochleae. Laryngoscope. 1987;97:836–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Leake PA, Hradek GT, Rebscher SJ, et al. Chronic intracochlear electrical stimulation induces selective survivial of spiral ganglion neurons in neonatally deaffened cats. Hearing Res. 1991;54:251–271. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(91)90120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leake PA, Hradek GT, Snyder RL. Chronic electrical stimulation by a cochlear implant promotes survival of spiral ganglion neurons after neonatal deafness. J. Comp. Neurol. 1999;412:543–562. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19991004)412:4<543::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Leake PA, Stakhovskaya O, Hradek GT, et al. Factors influencing neurotrophic effects of electrical stimulation in the deafened developing auditory system. Hear. Res. 2008;242:86–99. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Araki S, Kawano A, Seldon L, et al. Effects of chronic electrical stimulation on spiral ganglion neuron survival and size in deafened kittens. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:687–695. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199805000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li L, Parkins CW, Webster DB. Does electrical stimulation of deaf cochleae prevent spiral ganglion degeneration? 1999;133:27–39. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shepherd RK, Matsushima J, Martin RL, et al. Cochlear pathology following chronic electrical stimulation of the auditory nerve: II. Deafened kittens. Hear. Res. 1994;81:150–166. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Coco A, Epp SB, Fallon JB, et al. Does cochlear implantation and electrical stimulation affect residual hair cells and spiral ganglion neurons? Hear. Res. 2007;225:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Powell TPS, Erulkar SD. Transneuronal cell degeneration in the auditory relay nuclei of the cat. J. Anat. 1962;96:219–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.West CD, Harrison JM. Transneuronal cell atrophy in the deaf white cat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1973;151:377–398. doi: 10.1002/cne.901510406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Parks TN. Afferent influences on the development of the brain stem auditory nuclei of the chicken: otocyst ablation. J. Comp. Neurol. 1979;183:665–677. doi: 10.1002/cne.901830313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nordeen KW, Killackey HP, Kitzes LM. Ascending projections to the inferior colliculus following unilateral cochlear ablation in the neonatal gerbil, Meriones unguiculatus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1983;214:144–153. doi: 10.1002/cne.902140204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Moore DR, Kowalchuk NE. Auditory brainstem of the ferret: Effects of unilateral cochlear lesions on cochlear nucleus volume and projections to the inferior colliculus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1988;272:503–515. doi: 10.1002/cne.902720405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hardie NA, Martsi-McClintock A, Aitkin LM, et al. Neonatal sensorineural hearing loss affects synaptic density in the auditory midbrain. NeuroReport. 1998;9:2019–2022. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199806220-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kral A, Hartmann R, Tillein J, et al. Hearing after congenital deafness: central auditory plasticity and sensory deprivation. Cereb. Cortex. 2002;12:797–807. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.8.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Harris JA, Hardie NA, Bermingham-McDonogh O, et al. Gene expression differences over a critical period of afferent-dependent neuron survival in the mouse auditory brainstem. J. Comp. Neurol. 2005;493:460–474. doi: 10.1002/cne.20776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Müller M, Smolders JW. Shift in the cochlear place-frequency map after noise damage in the mouse. Neuroreport. 2005;16:1183–1187. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200508010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tirko NN, Ryugo DK. Synaptic plasticity in the medial superior olive of hearing, deaf, and cochlear-implanted cats. J. Comp. Neurol. 2012;520:2202–2217. doi: 10.1002/cne.23038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liberman MC. Single neuron labelling in the cat auditory nerve. Science. 1982b;216:1239–1241. doi: 10.1126/science.7079757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fekete DM, Rouiller EM, Liberman MC, et al. The central projections of intracellularly labeled auditory nerve fibers in cats. J. Comp. Neurol. 1984;229:432–450. doi: 10.1002/cne.902290311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Saada AA, Niparko JK, Ryugo DK. Morphological changes in the cochlear nucleus of congenitally deaf white cats. Brain Res. 1996;736:315–328. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00719-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Redd EE, Pongstaporn T, Ryugo DK. The effects of congenital deafness on auditory nerve synapses and globular bushy cells in cats. Hear. Res. 2000;147:160–174. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]