Abstract

Suspension-cultured Chenopodium album L. cells are capable of continuous, long-term growth on a boron-deficient medium. Compared with cultures grown with boron, these cultures contained more enlarged and detached cells, had increased turbidity due to the rupture of a small number of cells, and contained cells with an increased cell wall pore size. These characteristics were reversed by the addition of boric acid (≥7 μm) to the boron-deficient cells. C. album cells grown in the presence of 100 μm boric acid entered the stationary phase when they were not subcultured, and remained viable for at least 3 weeks. The transition from the growth phase to the stationary phase was accompanied by a decrease in the wall pore size. Cells grown without boric acid or with 7 μm boric acid were not able to reduce their wall pore size at the transition to the stationary phase. These cells could not be kept viable in the stationary phase, because they continued to expand and died as a result of wall rupture. The addition of 100 μm boric acid prevented wall rupture and the wall pore size was reduced to normal values. We conclude that boron is required to maintain the normal pore structure of the wall matrix and to mechanically stabilize the wall at growth termination.

The ultrastructure and physical properties of plant cell walls are known to be affected by boron deficiency (Kouchi and Kumazawa, 1976; Hirsch and Torrey, 1980; Fischer and Hecht-Buchholz, 1985; Matoh et al., 1992; Hu and Brown, 1994; Findeklee and Goldbach, 1996). Moreover, boron is predominantly localized in the cell wall when plants are grown with suboptimal boron (Loomis and Durst, 1991; Matoh et al., 1992; Hu and Brown, 1994; Hu et al., 1996). In radish, >80% of the cell wall boron is present in the pectic polysaccharide RG-II (Matoh et al., 1993; Kobayashi et al., 1996), which is now known to exist as a dimer that is cross-linked by a borate ester between two apiosyl residues (Kobayashi et al., 1996; O'Neill et al., 1996). Dimeric RG-II is unusually stable at low pH and is present in a large number of plant species (Ishii and Matsunaga, 1996; Kobayashi et al., 1996, 1997; Matoh et al., 1996; O'Neill et al., 1996; Pellerin et al., 1996; Kaneko et al., 1997). The widespread occurrence and conserved structure of RG-II (Darvill et al., 1978; O'Neill et al., 1990) have led to the suggestion that borate ester cross-linked RG-II is required for the development of a normal cell wall (O'Neill et al., 1996; Matoh, 1997).

One approach for determining the function of boron in plant cell walls is to compare the responses to boron deficiency of growing plant cells that are dividing and synthesizing primary cell walls with those of growth-limited plant cells in which the synthesis of primary cell walls is negligible. Suspension-cultured cells are well suited for this purpose because they may be reversibly transferred from a growth phase to a stationary phase. Continuous cell growth phase is maintained by frequent transfer of the cells into new growth medium (King, 1981; Kandarakov et al., 1994), whereas a stationary cell population is obtained by feeding the cells with Suc and by not subculturing them. Cells in the stationary phase are characterized by mechanically stabilized primary walls and reduced biosynthetic activity. Here we describe the responses of suspension-cultured Chenopodium album L. cells in the growth and stationary phases to boron deficiency. These cells have a high specific-growth rate, no significant lag phase, and reproducible changes in their wall pore size during the transition from the growth phase to the stationary phase (Titel et al., 1997).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

Chenopodium album L. cells (strain C.9.1. described by Knösche and Günther, 1988) were grown on a modified Murashige and Skoog medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) containing KH2PO4 (0.4 g L−1), Suc (40 g L−1), myo-inositol (100 mg L−1), thiamine hydrochloride (0.4 mg L−1), 2,4-D (0.3 mg L−1), and 6-furfurylaminopurine (0.1 mg L−1). The boron concentration of the standard medium was varied as required. Cultures (150 mL) were grown at 27°C in 500-mL flasks under dim light on a rotary shaker at 200 rpm. Media with low boron concentrations (≤7 μm) were prepared in autoclavable polypropylene containers with bidistilled water from concentrated stock solutions (macroelements, 20-fold; microelements, 100-fold; and Suc, 10-fold) that had been assayed for the absence of boron (detection limit, 2 μm) by inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry (Unicam 701, Unicam Ltd., Cambridge, UK). Suc stock solutions were passed over a column with a boron-absorbing ion-exchange resin (IRA-743, Sigma) before autoclaving (20 volumes/bed volume). All reagents used were of analytical grade. At subcultivations cells grown at low boron concentration or “without boron” remained in the same quartz vessels, and the harvested suspension volume was replaced by fresh boron-deficient medium. The boron content in fresh medium was determined colorimetrically using curcumin after extraction of boric acid from the acidified medium with hexanediol/chloroform (Mair and Day, 1972). The procedure was modified by reducing the dye concentration from 0.375% to 0.05% and by using water to extract the uncomplexed dye from the organic phase. This method has a detection limit of 0.03 μm boron.

Propagation Culture

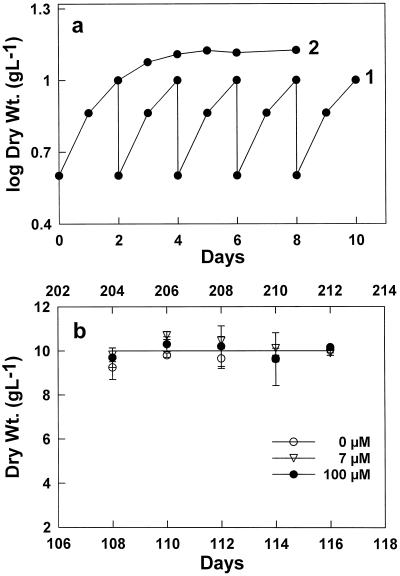

Cultures that had been previously subcultivated weekly (1:6 dilution) were subcultivated at high frequency (2:5 dilution every 2nd d). Under these conditions the transition to the stationary phase did not occur because the cells were diluted with fresh medium before the nutrients became limiting and cell number reached an inhibiting level (Fig. 1a, curve 1). This high-frequency subcultivation ensured that the culture was continuously maintained (>180 subcultivations) in the growth phase and was used to grow cells in the absence of added boron and at different boron concentrations. The final biomass concentration (ct) at subcultivation time and the initial biomass concentration (co) were constant (see Fig. 1b) and, therefore, the mean specific-growth rate (μ = 1/2 d [ln ct − ln 2]) equals the mean dilution rate (r = 1/2 d [ln 5 − ln 2] = 0.46 d−1). This specific-growth rate is only slightly below the maximum growth rate of C. album.

Figure 1.

Changes in the dry weights of C. album cells during their growth phase and during the transition from the growth phase to the stationary phase. a, Changes in the dry weights of growing cells that were diluted with fresh medium every 2 d (curve 1). Dry weight increase of the cells in transition from the growth phase to the stationary phase (curve 2); before the transition to the stationary phase, the cells had been maintained for 60 passages in the growth phase (100 μm boric acid). The dilution of the cells with fresh medium was at time 0, and at d 2 Suc (2 g/100 mL) was added. b, Maximum dry weights of cells grown continuously with a high frequency of subcultivation (every 2 d) at different boron concentrations. Dry weights (Dry Wt.) were determined before subcultivation. The time in days is the length of time that the cells had been grown continuously at the given boron concentration. The upper x axis is the time for cells grown with 100 and 7 μm boron and the lower x axis is the time for cells grown in the absence of added boron.

Transition to the Stationary Phase

A sterile solution of Suc (5 mL, 400 g L−1) was added to cells (100 mL) that had been subcultured every 2nd d in propagation culture for more than 20 cycles, and the cells were then maintained axenically without the addition of fresh medium. These conditions initially generated cells in transition from the growing phase to the stationary phase and then cells in the stationary phase. The cells were considered to be in the stationary phase when their fresh and dry weights did not increase (Fig. 1a, curve 2) and there was no mitosis. The cells were maintained for long periods in the stationary phase by the addition of Suc when the concentration of solubles decreased to less than 0.5% on the Suc scale of the refractometer. Cell viability remained high even though the growth rate decreased rapidly when the cells were maintained on standard medium containing 100 μm boron. The pH of the medium changed from 5.2 (autoclaved medium) to approximately 3.8 during the 1st d, increased to approximately 4.9 by the 2nd d, and reached approximately 6.0 in the stationary phase.

Cell Viability and Release of Organelles into the Medium

Cell viability was determined qualitatively by mixing small volumes of the cells with Evans blue (Gaff and Okong'o-Ogola, 1971) to give a dye concentration of 0.05%. Dead cells stained deeply and were readily distinguished from viable cells after an incubation time of 10 min. The portion of dead cells was quantified by determining the FAV. This is a measure of the volume of dead cells and cell walls in the cell clusters and was determined, by a polarimetric method, as the difference between the partition volumes of methyl β-d-arabinopyranoside (Sigma) and Dextran T250 (Pharmacia) in filtered cells and expressed on a fresh-weight basis (Fleischer and Ehwald, 1995). The release of organelles from dead cells caused the turbidity of the medium to increase and was estimated from the A490 of the filtered medium.

Determination of the Fresh and Dry Weights of Cells

At the designated sampling times cell cultures (10 mL) were filtered through a G2 glass frit and the turbidity and Suc concentration (refractive index) of the filtrate were determined. The cells were washed with deionized water (2 × 10 mL) and then drained with a flow of air before determination of their fresh weights. The cells were dried for 24 h at 105°C and their dry weights were then determined.

Generation of Denatured Cells for Analysis of Particle Size and Wall Pore Size

Cells for particle and wall pore size measurements were denatured by treating packed cells on a filter with a solution (1 bed volume) containing ethanol (80%), water (19%), and acetic acid (1%), and then with an excess of 80% ethanol. The denatured cells were suspended in 96% ethanol and stored at 6°C.

Determination of the Pore Size of Cell Walls Using Dextran-Permeation Analysis

Denatured and ethanol-saturated cells (from approximately 2 g fresh weight of cells) were rehydrated and thoroughly washed on a polypropylene filter (thickness, 0.5 mm; pore size, 35 μm) with 1 mm CaCl2 and then with potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, containing 100 mm NaCl and 0.05% NaN3. The excess water was removed by gentle suction and the material was then treated for 30 min with a polydisperse dextran-probing solution (1.5–2.0 mL). The size dependence of dextran partitioning was analyzed by size-exclusion chromatography, as described by Woehlecke and Ehwald (1995) and Titel et al. (1997).

Particle-Size Analysis of C. album Cells and Cell Clusters

Ethanol-saturated cells were washed with 1 mm CaCl2 to remove the ethanol. The cell clusters were disaggregated to single cells by sonicating (240 W, 35 kHz, 30°C) a suspension of cells (1 volume) for 1 h in 5% chromic acid (10 volumes) in a Sonorex Super sonicator (Bandelin GmbH, Berlin, Germany). The suspension was then sheared by two passages through a fine needle (0.8 mm in diameter and 40 mm in length). Light-microscopic analysis showed that the cell clumps were completely disintegrated to single cells. The volume fractions of different particle size classes in disintegrated and nondisintegrated cell clusters were determined with a laser analyzer (Analysette 22, Fritsch GmbH, Idar-Oberstein, Germany).

Cell numbers in the suspension were calculated from the fresh weight and the size distribution of the cells in the disintegrated samples. The following assumptions were used: the cell volume per gram fresh weight is 0.7 mL (Fleischer and Ehwald, 1995) and the cells have a spherical shape. The single cells obtained by the disintegrating treatment were more or less spherical.

RESULTS

Growth of C. album Cells on Media with Different Boron Concentrations

C. album cells have a mean specific-growth rate of approximately 0.5 d−1 during the first 2 d of batch culture in standard medium and the stationary phase is reached by the 5th d (compare Titel et al., 1997). When a boron-deficient medium is used, the cells die after the third or fourth transfer at the end of the growth phase, although there is no marked inhibition in dry-weight increase before loss of cell viability. Cell death in the batch-culture regime is preceded by an increase in cell size and a slight decrease in flavonol content, and is accompanied by a strong increase in the turbidity of the liquid medium.

C. album cells can be kept continuously in their growth phase by subculturing every 2nd d at a dilution rate of 2:5. Therefore, the effect of boron deficiency on cell division and growth was determined under these conditions. Cells were first grown on standard medium and on a medium containing 7 μm boron. After approximately 50 transfers the cells' ability to grow in the absence of added boron (<0.1 μm) was determined. Somewhat unexpectedly, the cells grew in the absence of added boron and their dry weights did not differ significantly from those of cells grown in the presence of 7 and 100 μm boron (Fig. 1b). The growth rate of the boron-deficient cells remained constant for more than 180 transfers. The transfer of cells from the boron-containing medium to the medium without added boron was done four times and in all cases a specific growth rate of 0.46 d−1 was maintained.

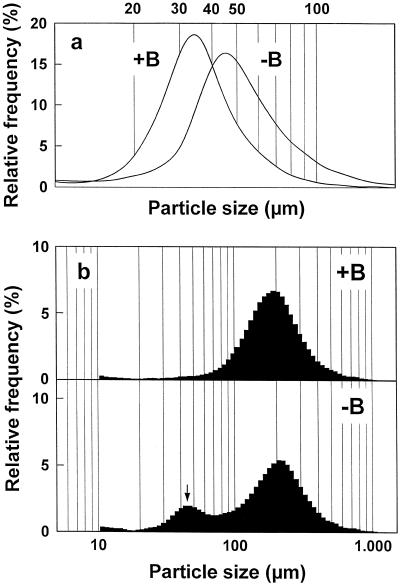

Cells growing without added boron and those growing with 7 and 100 μm boron differed visually even though their growth rates were similar and all cultures did not contain a significant fraction of dead cells. Cultures without added boron contained increased numbers of single cells or cell pairs and, most notably, highly enlarged cells (Figs. 2 and 4). Because the cells are larger under boron deficiency, the smaller number of cells per gram fresh weight (4.23 × 107 in the boron-deficient culture and 5.91 × 107 in the control culture) may be correlated with fewer chromoplasts on a volume and dry-weight basis. This may explain the observed reduction in flavonol content (to 75% of the control). Growing cells without boron consistently caused a discernible increase in the turbidity of the medium. This turbidity increase was less pronounced in the growing cultures than in cultures at the stationary phase, but in both cases was caused by the release of organelles through cell bursting.

Figure 2.

Particle-size distribution curves of disaggregated and untreated clusters of growth-phase C. album cells. a, Particle-size distribution curves of suspension-cultured C. album cells after disaggregating treatment without boron (−B) or with 100 μm boron (+B). The particle-size distribution after disaggregating treatment is equivalent to the cell-size distribution. b, Particle-size distribution curves of untreated suspension-cultured C. album cell clusters grown with or without boron. The peak at approximately 45 μm (↓) corresponds to single cells that have separated from cell clusters during their cultivation. Particle size is equivalent to the diameter of a spherical particle and was determined with a laser particle-size analyzer.

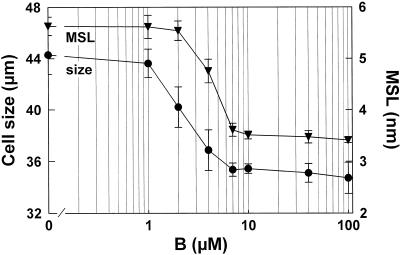

Figure 4.

Effect of boron concentrations on the cell size and the mean size limits (MSL) of the walls of C. album cells. ▾, Mean size limits ± sd (n = 10). •, Cell size (mode of the cell size distribution) of mechanically disaggregated clusters ± sd (n = 8). Cells were grown continuously in media containing different boric acid concentrations. With the exception of the control, cells were previously grown without boron and, before analysis, subcultivated at least five times in media of the given boron concentrations.

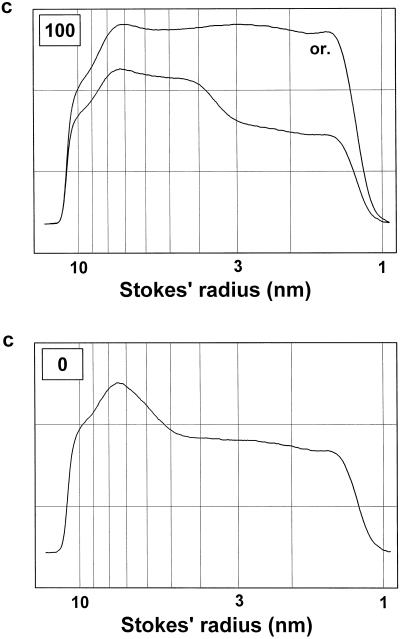

The size limits of the cell wall for permeation by dextrans were determined by treating the denatured cells with a polydisperse dextran-probing solution (Woehlecke and Ehwald, 1995). Large dextran molecules are excluded from the cells and remain in the probing solution, whereas smaller dextrans penetrate the wall into the cell lumina and are partially removed from the probing solution. The dextrans that did not diffuse into the cell lumina were analyzed by high-performance size-exclusion chromatography (Fig. 3). The elution profiles of the cell-exposed dextran solutions contained “steps,” more gradual changes attributable to the size-dependent diffusion of the dextrans into the cell lumina (Fig. 3). The curves were analyzed as described by Woehlecke and Ehwald (1995) to determine the size limits for approximate equilibration with 95%, 50%, and 5% of the inner cell volume, which correspond to the lower size limit, the mean size limit, and the upper size limit of cell wall permeation, respectively. In cells growing in boron-deficient medium, all of these size limits were greatly increased (Table I).

Figure 3.

Particle-size distribution profiles of the polydisperse dextran-probing solutions after equilibration with denatured growth-phase cells. Denatured cells derived from cells grown in the presence of 100 μm boron (top) and in the absence of added boron (bottom) were equilibrated for 30 min with the polydisperse dextran-probing solution. The particle-size distribution profile of the dextrans was modified by their partial diffusion into the cell lumina. Untreated (or.) and treated dextran solutions were fractionated by size-exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 HR 10/30 column. The eluate was monitored with a polarimetric detector. The dextran concentration (c) is given in arbitrary units. The Stokes' radii of the dextrans were derived from their elution times using a calibration function (Woehlecke and Ehwald, 1995).

Table I.

The wall-pore size limits of growing and stationary C. album cells

| Phase and Size Limit | Boric Acid Concentration

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 μma | 7 μm | 100 μm | |

| nm | |||

| Growthb | |||

| LSLc | 4.19 ± 0.32 | 2.73 ± 0.14 | 2.62 ± 0.12 |

| MSLd | 5.62 ± 0.20 | 3.60 ± 0.13 | 3.41 ± 0.05 |

| USLe | 8.34 ± 0.28 | 5.66 ± 0.20 | 5.16 ± 0.44 |

| Stationaryf | |||

| LSL | Viability lost | 2.75 ± 0.30 | 2.26 ± 0.10 |

| MSL | n.d.g | 2.85 ± 0.18 | |

| USL | n.d. | 4.12 ± 0.13 | |

Cells were grown in media containing different boric acid concentrations. Samples were taken 2 d after their last subcultivation (growing cells) or after a subsequent 4 d of cultivation in the presence of Suc (stationary cells).

<0.1 μm boric acid.

Mean ± sd of 10 independent replicates.

LSL, Lower size limit of permeation; critical Stokes' radius for equilibration of all cell lumina.

MSL, Mean size limit; Stokes' radius for equilibration in one-half of the cell volume.

USL, Upper size limit of permeation; critical Stokes' radius for complete exclusion from cell lumina.

Mean ± sd of at least six independent replicates.

n.d., Not determinable; upper size limit beyond the range of analysis (>9 nm).

To estimate the boron concentrations that are required to decrease wall pore size, reduce medium turbidity, and decrease the number of single cells, cultures grown continuously without boron were transferred to media with boron concentrations between 1 and 100 μm. The mean size limit of cell wall permeation was comparable to that of control cells when the boron concentration was 7 μm (boron content of the cells at harvest time was approximately 8 μg g−1 dry weight). No change in the pore size of the cell wall was obtained with 1 or 2 μm boron (Fig. 4), whereas 4 μm boron resulted in an intermediate pore size. The apparent half-effect concentration was 4.5 μm. The dependence of cell size on boron concentration was similar to that of the wall pore size, although 2 μm boron did have a discernible effect (Fig. 4). In contrast, the lowest boron concentrations (1 and 2 μm) were sufficient to reduce the mechanical cell breakdown (turbidity) and to decrease the number of single cells (Table II).

Table II.

The effect of the addition of boric acid on cell rupture and the frequency of single cells and small clusters of C. album cells

| Parameter | Boric Acid Concentration

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 μma | 1 μm | 2 μm | 100 μm | |

| A490b | 0.077 ± 0.023 | 0.039 ± 0.012 | 0.039 ± 0.011 | 0.017 ± 0.006 |

| Frequency of particles (% of total particle volume)c | ||||

| <50 μm (mainly single cells) | 11.50 ± 2.46 | 6.63 ± 0.74 | 4.60 ± 0.48 | 4.22 ± 0.64 |

| <100 μm (includes small cluster) | 27.68 ± 4.82 | 16.67 ± 1.85 | 10.64 ± 0.98 | 12.68 ± 2.12 |

Cells were grown continuously in media containing different boric acid concentrations. Cells with 1 and 2 μm boron were previously grown without boron and, before analysis, subcultivated at least five times in media of the given boron concentrations. Cell rupture was estimated by measuring the A490 of the medium, and particle size was determined with a laser analyzer.

<0.1 μm boric acid.

Mean ± sd of at least 10 independent replicates.

Compare Figure 2 (mean ± sd of 10 independent replicates).

Transition from the Growth Phase to the Stationary Phase for Cells Grown in the Presence of Different Boron Concentrations

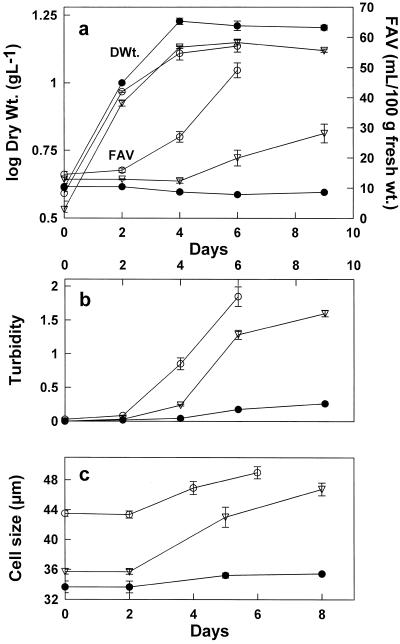

The growth rate of C. album cells was significantly reduced on the 4th d of cultivation if the cultures were fed with Suc and not diluted with fresh medium (Fig. 1a). Cell wall expansion in stationary control suspensions was strongly reduced, although no secondary walls were formed (cells resume growth after subcultivation). At the transition to the stationary phase intercellular spaces increased, meristematic spheric or oval cell complexes with plane-segmenting walls disappeared, and cells became nearly sphere shaped. Stationary cells were smaller and more uniform when obtained from cultures grown with 100 rather than with 7 μm boron (Fig. 5). The stationary cells (100 μm boron) remained viable for more than 3 weeks without a significant increase in cell size. The cell diameter increased at the transition phase and remained constant during the stationary phase. Stationary control cells did not release turbid material and their FAV remained low if Suc depletion was prevented (Fig. 6, a and b). When cells grown in the absence of boron or at 7 μm boron were fed with Suc and not diluted, their dry-weight increase was similar to that of control cells (Fig. 6a). However, the turbidity of the medium, an indication of cell bursting, increased at the onset of the stationary phase, as did the number of dead cells and the FAV (Fig. 6, a and b). The FAV is a measure of the liquid-volume fraction of cell walls and dead cells. A FAV of 50% corresponds to the death of most cells (see Fig. 6a), since the FAV includes neither liquid volumes within intercellular spaces and surface film nor the volumes of solid materials (Fleischer and Ehwald, 1995). Almost complete cell damage was confirmed by staining with Evans blue. In addition, the size of the cells grown without boron or with 7 μm boron increased during the transition to the stationary phase (Fig. 6c).

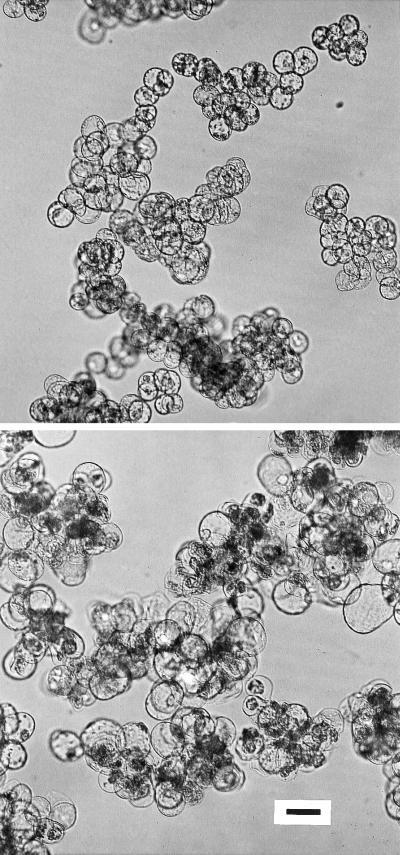

Figure 5.

Light micrographs of clusters of stationary-phase C. album cells obtained from cultures grown with 100 or 7 μm boric acid. Before the transition to the stationary phase the cells were grown continuously in medium containing 100 μm boron (top) or 7 μm boron (bottom). Scale bar, 50 μm. Cells were photographed 9 d after their last subcultivation.

Figure 6.

Effect of boron concentrations on the dry weight, FAV, turbidity, and cell size during the transition of cells from the growth to the stationary phase. Cells grown continuously for 125 passages in the absence of added boron (○), 7 μm boron (▿), or 100 μm boron (•) were not diluted with fresh medium but supplied with Suc (2%, w/v) 2 d after the last subcultivation. a, Increase in dry weight (DWt.) and FAV. b, Turbidity of the filtered medium (A490). c, Cell size (mode of the size distribution of the mechanically disaggregated cell clusters). The data are means ± sd obtained from three independent experiments.

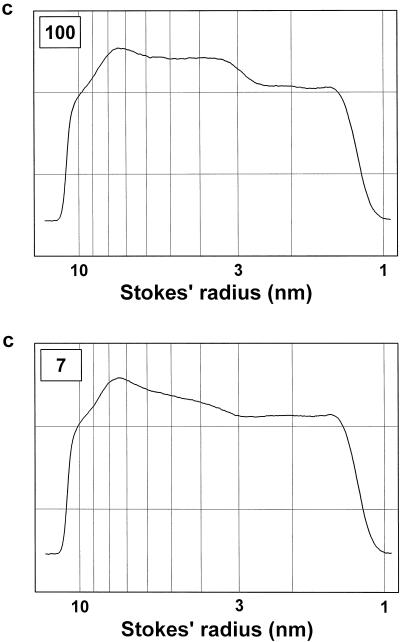

Stationary cells pregrown with 7 μm boron were characterized by a broadening of the dextran-permeation region due to selective increase of the upper size limit to values beyond the range of analysis (Fig. 7; Table I). The strong increase in the upper size limit of boron-deficient stationary cultures may be explained at least partly by ruptured cells. In stationary boron-deficient cells only the lower size limit could be easily compared with that of the control. Whereas the control showed a significant decrease in all size limits at the transition to the stationary phase, there was no decrease in the lower size limit of boron-deficient cells (Table I).

Figure 7.

Pore-size distribution profiles of the polydisperse dextran-probing solutions after equilibration with denatured stationary cells. Denatured stationary cells derived from cells grown in medium containing 100 μm boron (top) or 7 μm boron (bottom). The pore-size distribution profile of the untreated dextran-probing solution is shown in Figure 3. c, Dextran concentration.

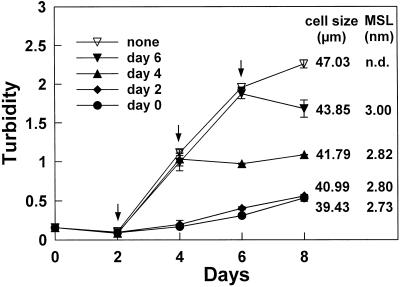

The progression of cell necrosis in the stationary phase was interrupted by supplementing the media with boron (Fig. 8). The addition of boron (100 μm) to boron-deficient cells during the transition phase stopped further cell enlargement and organelle release, and after 8 d the wall-pore size of these cells and control cells were comparable (Table I; Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

The effect of 100 μm boron on cells grown at 7 μm boron during their transition to the stationary phase. Cells were grown in medium containing 7 μm boron and at time 0 kept without dilution and allowed to reach the stationary phase. Boric acid (100 μm) was added at time 0 or at the times indicated by the arrows. Suc was added at d 2. Cell rupture was followed by measuring the turbidity (A490) of the filtered medium. Cell size (mode of the size distribution of the mechanically disaggregated cell clusters) and the mean size limit (MSL) of the walls were measured at d 8. n.d., Not determinable; upper size limit beyond the range of analysis (>9 nm).

A reduction in water potential by Suc (10 g L−1, 0.8 MPa), which is sufficient to compensate the osmotic potential of the cell sap in C. album (Fleischer and Ehwald, 1995), caused a transient (3–4 d) halt in the increase in the fresh weight and cell size that typically occurs during the transition of boron-deficient cells to the stationary phase. The reduction in turgor also caused a marked reduction in the increase of turbidity and reduced the percentage of dead cells (stained with Evans blue; data not shown), but had no significant effect on the size limits of cell wall pores (Table III).

Table III.

The effect of reduced osmotic potential on the enlargement, rupture, and wall-pore size of stationary-phase C. album cells maintained at low boric acid concentration

| Parametera | Boric Acid Concentration

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 μm | 100 μm | |||

| Reduction in osmotic potential of the medium (MPa) | 0.16 | 0.80 | 0.16 | 0.80 |

| Fresh wt (g L−1) | ||||

| d 2 | 187.79 ± 8.21 | 187.79 ± 8.21 | 171.38 ± 5.20 | 171.38 ± 5.20 |

| d 5 | 276.42 ± 3.86 | 189.78 ± 2.26 | 264.63 ± 13.27 | 195.78 ± 4.16 |

| Cell size (μm) | ||||

| d 2 | 35.68 ± 0.33 | 35.68 ± 0.33 | 33.66 ± 0.96 | 33.66 ± 0.96 |

| d 5 | 43.03 ± 1.36 | 35.24 ± 0.85 | 35.22 ± 0.39 | 33.90 ± 0.76 |

| MSLb(nm) | ||||

| d 2 | 3.68 ± 0.08 | 3.68 ± 0.08 | 3.30 ± 0.10 | 3.30 ± 0.10 |

| d 5 | n.d.c | n.d. | 2.75 ± 0.05 | 2.77 ± 0.11 |

| A490 | ||||

| d 2 | 0.055 ± 0.011 | 0.055 ± 0.011 | 0.019 ± 0.003 | 0.019 ± 0.003 |

| d 5 | 1.050 ± 0.118 | 0.420 ± 0.058 | 0.042 ± 0.013 | 0.026 ± 0.007 |

Cells grown continuously in the presence of 7 or 100 μm boric acid were cultivated without dilution to reach their stationary phase. The media were supplemented with Suc (20 or 100 g L−1) at d 2 to determine the effect of reduced turgor pressure on the development of boron-deficiency symptoms at the onset of the stationary phase.

Each value represents the mean ± sd of three independent replicates.

MSL, Mean size limit; Stokes' radius for equilibration in one-half of the cell volume.

n.d., Not determinable, upper size limit beyond the range of analysis (>9 nm).

DISCUSSION

The Boron Requirement for Plant Cell Division and Growth

All vascular plants need boron (Augsten and Eichhorn, 1976; Dugger, 1983; Loomis and Durst, 1992), but this does not necessarily imply that boron is essential for the viability of all suspension-cultured higher plant cells. Our results show a striking difference in the boron requirement of growing and stationary C. album cells and provide evidence that these cells continue to divide and grow even in the absence of added boron. However, the presence of nanomolar concentrations of boron in the growth medium cannot be excluded, nor can the possibility that submicromolar levels of boron are essential for cell growth.

It is unlikely that long-term propagation of C. album cells at a low boron concentration resulted in the selection of cells with both an irreversibly altered wall structure and a low boron demand, because these cells have been transferred several times from standard medium to boron-deficient medium without a reduction in their mean specific-growth rate. Furthermore, the symptoms of boron deficiency are stable and are reversed by transferring growing cells from a medium without boron to the standard medium. Finally, the sensitivity of stationary cells to boron deficiency is not reduced by long-term growth without boron.

The rupture of a small number of cells in the boron-deficient growth medium may be attributable to a subpopulation of cells that have left the cell-division cycle and entered the stationary phase. These cells, like cells in the early stationary phase, would then be considerably more sensitive to boron deficiency (Fig. 6). The presence of a subpopulation of stationary cells may not be completely prevented even by the high frequency of subcultivation.

Although in the whole plant it is difficult to separate the direct and indirect effects of boron deficiency on early meristematic growth because meristems are under correlative control by other plant parts, cell enlargement is believed to require higher boron levels than cell division (Torssell, 1956; Slack and Whittington, 1964; Birnbaum et al., 1974; Kouchi and Kumazawa, 1976; Dell and Huang, 1997). Our findings are consistent with a lower boron requirement for cell division growth, but are in apparent contrast to studies reporting growth reduction of suspension-cultured cells at suboptimal boron concentrations (Seresinhe and Oertli, 1991; Matoh et al., 1992; Hu and Brown, 1994). Those studies used batch cultures that were made boron deficient by washing the cells with a boron-deficient medium and thus are not comparable to our growth conditions. By this treatment, conditioning factors are removed and a pronounced lag phase is induced. Suspension-cultured plant cells may be more sensitive to boron deficiency during the lag phase than in the growth phase. However, suspension cultures appear to differ in their ability to maintain high rates of propagation growth at low boron concentrations. For example, a culture derived from carrot grows in the absence of added boron, whereas a culture of Dioscorea deltoidea Wall. requires boron to maintain continuous growth (A. Fleischer, unpublished results).

The Effect of Boron on Cell Wall Structure

C. album cells maintain a high specific-growth rate for an apparently unlimited period of time, even at extremely low boron concentrations in the growth medium. Nevertheless, symptoms of boron deficiency that indicate an altered cell wall structure are observed in these cells. These symptoms, which include decreased cell wall resistance to mechanical stress (cell-cluster disintegration, uncontrolled cell expansion, and the bursting of cells), are comparable to the effects of boron deficiency in other plants (Loomis and Durst, 1992). The high frequency of single cells and small clusters of cells (see Fig. 2b) is consistent with the weakening of wall-to-wall contact between cells; a weakened middle lamella has been reported to be a symptom of boron deficiency in plant organs (Loomis and Durst, 1992; Marschner, 1995). We have also shown that C. album cells grown in the absence of boron are larger than the cells grown with boron. Again, such a result is consistent with the reported uncontrolled enlargement of cells in the growing regions of boron-deficient plants (Loomis and Durst, 1992).

The results of our study provide evidence that in a boron-deficient medium cell death is caused primarily by the weakening of the cell wall. The death of resting cells is accompanied by the release of cell organelles, which is indicative of cell wall rupture. The rupture of boron-deficient cell walls results from plasmoptysis, a phenomenon in which localized bursting of the cell wall causes damage to the plasma membrane (Küster, 1958). Plasmoptysis may be induced by local weakening of cell walls (defect plasmoptysis) or by an increase in turgor pressure (osmotic plasmoptysis). Plasmoptysis may account for the tip bursting that occurs at low boron concentrations during pollen-tube growth of some plants (Schmucker, 1934) and may also account for the increased solute efflux and cell damage in boron-deficient plants that has been reported (Cakmak et al., 1995). Solute leakage may be misinterpreted as indicating a high permeability of lipid membranes if plasmoptysis is not taken into account (compare e.g. Simon, 1977; Ehwald et al., 1980, 1984).

To our knowledge, our data are the first to show that pore size in the cell wall is markedly affected by the presence or absence of boron. The pore size of the cell walls, i.e. the size of pores limiting unrestricted diffusion of polymers through the wall, has been shown to depend on the concentration and/or conformation of the pectic polymers (Baron-Epel et al., 1988; Ehwald et al., 1992; Carpita and Gibeaut, 1993). The increased pore size limits of the wall in the boron-deficient cells is indicative of a disorganized pectic network and may result from the absence of borate ester cross-linked RG-II.

We suggest that in the cell wall, borate ester cross-linked RG-II regulates the macroscopic conformation of the pectin network and that the formation of borate ester cross-linked RG-II is required for normal cell growth. We also suggest that the boron-dependent pectin conformation, which itself may control the permeation of macromolecules through the wall, will affect the accessibility of load-bearing structures to wall-loosening protein molecules, since the size limits of cell wall permeation and wall extensibility are reduced at the transition to the stationary phase and both changes require high boron concentrations. Another possibility to explain the observed parallel changes of wall extensibility and pore size might be the influence of pore size on the retention of polymer compounds (Bonilla et al., 1997) that are necessary for wall stiffening, e.g. extensins and Pro-rich proteins (Carpita and Gibeaut, 1993).

The increase in the mean size limit of cell wall permeation of growing cells was the most sensitive of the boron-deficiency symptoms observed. The restoration of the mean size limit of cell wall permeation to normal values required higher boron concentrations than were required to reduce the turbidity of the growth medium and to decrease the number of single cells (compare Fig. 4 and Table II). The ability of boron to alter cell wall pore size was not a secondary effect resulting from increased wall expansion, since it also occurred at reduced water potential, under which cell enlargement was completely prevented (Table III). Moreover, the wall pore size of boron-deficient enlarged cells was reduced by adding boron to the cells (Fig. 8).

Stationary-phase cells had a much higher boron requirement than growing cells. For example, 7 μm boron was sufficient to keep the porosity values of propagating cells comparable to those of control cells (Fig. 4; Table I), but was not sufficient for the decrease of the wall pore size at the transition from the growth phase to the stationary phase (Fig. 7; Table I). A decrease of all wall size limits at the transition to the stationary phase is characteristic of control cells (Table I) (Titel et al., 1997).

The disappearance of boron-deficiency symptoms in stationary-phase cells after the addition of boron (Fig. 8) suggests that boron affects wall structure even in nongrowing cells, in which an increase in cell wall dry weight is negligible. In C. album cells, boron appears to be essential for wall stiffening at growth termination. This may allow the cells to maintain their size within certain limits and over long periods of time, when genes for the synthesis of wall polymers are not expressed and the deposition of new wall polymers does not occur. The boron-deficiency symptoms most likely result from insufficient boron in the cell wall rather than from a boron deficiency in the cytoplasm, because at low boron concentrations the cell wall boron is the predominant boron pool in suspension-cultured cells and higher plant tissues (Loomis and Durst, 1991; Matoh et al., 1992; Hu and Brown, 1994; Hu et al., 1996).

In summary, we have shown that C. album cells grow in the absence of added boron and that several cell wall-related symptoms of boron deficiency in growing and stationary cells can be examined. These deficiency symptoms are reversed by the addition of boron to the cells. For preventing boron-deficiency symptoms much higher boron concentrations are necessary in the stationary phase than in the growth phase. It is not known if the failure to form a borate ester cross-linked RG-II dimer is directly responsible for the effects of boron deficiency on wall structure. Determining the monomeric RG-II content of boron-deficient C. album cell walls and determining if the amount of RG-II in their walls increases at the onset of the stationary phase may provide evidence for the physiological role of this boron-binding pectic polysaccharide.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Dr. M.A. O'Neill (Complex Carbohydrate Research Center, The University of Georgia, Athens) for critical review and improvement of the manuscript.

Abbreviations:

- FAV

free apoplasmic volume

- RG-II

rhamnogalacturonan II

Footnotes

This research was supported by grant no. Eh 14471-1 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Bonn, Germany.

LITERATURE CITED

- Augsten H, Eichhorn M. Biochemie und Physiologie der Borwirkung bei Pflanzen. Biol Rundsch. 1976;14:268–285. [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Epel O, Gharyal PK, Schindler M. Pectins as mediators of wall porosity in soybean cells. Planta. 1988;175:389–395. doi: 10.1007/BF00396345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum EH, Beasley CA, Dugger WM. Boron deficiency in unfertilized cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) ovules grown in vitro. Plant Physiol. 1974;54:931–935. doi: 10.1104/pp.54.6.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla I, Mergold-Villasenor C, Campos ME, Sanchez N, Perez H, Lopez L, Castrejon L, Sanchez F, Cassab GI. The aberrant cell walls of boron-deficient bean root nodules have no covalently bound hydroxyproline-/proline-rich proteins. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:1329–1340. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.4.1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cakmak I, Kurz H, Marschner H. Short-term effects of boron, germanium and high light intensity of membrane permeability in boron deficient leaves of sunflower. Physiol Plant. 1995;95:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Carpita NC, Gibeaut DM. Structural models of primary cell walls in flowering plants: consistency of molecular structure with the physical properties of the walls during growth. Plant J. 1993;3:1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.1993.tb00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darvill AG, McNeil M, Albersheim P. Structure of plant cell walls. VIII. A new pectic polysaccharide. Plant Physiol. 1978;62:418–422. doi: 10.1104/pp.62.3.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell B, Huang L. Physiological response of plants to low boron. Plant Soil. 1997;193:103–120. [Google Scholar]

- Dugger WM. Boron in plant metabolism. In: Läuchli A, Bieleski RL, editors. Encyclopedia of Plant Physiology, Vol 15B: Inorganic Plant Nutrition. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1983. pp. 626–650. [Google Scholar]

- Ehwald R, Kowallik D, Meshcheryakov AB, Kholodova VP. Sucrose leakage from isolated parenchyma of sugar beet roots. J Exp Bot. 1980;31:607–620. [Google Scholar]

- Ehwald R, Richter E, Schlangstaedt M. Solute leakage from the isolated parenchyma of Allium cepa and Kalanchoe daigremontiana. J Exp Bot. 1984;35:1095–1103. [Google Scholar]

- Ehwald R, Woehlecke H, Titel C. Cell wall microcapsules with different porosity from suspension cultured Chenopodium album. Phytochemistry. 1992;31:3033–3038. [Google Scholar]

- Findeklee P, Goldbach HE. Rapid effects of boron deficiency on cell wall elasticity modulus in Cucurbita pepo roots. Bot Acta. 1996;109:463–465. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer G, Hecht-Buchholz C. The influence of boron deficiency on glandular scale development and structure in Mentha piperita. Planta Med. 1985;5:371–377. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-969523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer A, Ehwald R. The free space of sugars in plant tissues: external film and apoplastic volume. J Exp Bot. 1995;46:647–654. [Google Scholar]

- Gaff DF, Okong'o-Ogola O. The use of non-permeating pigments for testing the survival of cells. J Exp Bot. 1971;22:756–761. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch AM, Torrey JG. Ultrastructural changes in sunflower root cells in relation to boron deficiency and added auxin. Can J Bot. 1980;58:856–866. [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Brown PH. Localization of boron in cell walls of squash and tobacco and its association with pectin. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:681–689. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.2.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Brown PH, Labavitch JH. Species variability in boron requirement is correlated with cell wall pectin. J Exp Bot. 1996;47:227–232. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T, Matsunaga T. Isolation and characterization of a boron-rhamnogalacturonan II complex from cell walls of sugar beet pulp. Carbohydr Res. 1996;284:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kandarakov OF, Vorob'ev AS, Nosov AM. Biosynthetic characteristics of Dioscorea deltoidea cell population grown in continuous culture. Russ J Plant Physiol. 1994;41:805–809. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko S, Ishii T, Matsunaga T. A boron-rhamnogalacturonan II complex from bamboo shoot cell walls. Phytochemistry. 1997;44:243–248. [Google Scholar]

- King PJ. Plant tissue culture and the cell cycle. In: Fiechter A, editor. Plant Cell Cultures II. Akademie- Berlin: Verlag; 1981. pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Knösche R, Günther G. A cell division cycle in suspension cultures from Chenopodium album with unspecific arrest at G1 and G2 phase under stationary growth conditions. Biol Zentralbl. 1988;107:653–661. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Matoh T, Azuma J. Two chains of rhamnogalacturonan II are cross-linked by borate-diol ester bonds in higher plant cell walls. Plant Physiol. 1996;110:1017–1020. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.3.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Ohno K, Matoh T. Boron nutrition of cultured tobacco BY-2 cells. II. Characterization of the boron-polysaccharide complex. Plant Cell Physiol. 1997;38:676–683. [Google Scholar]

- Kouchi H, Kumazawa K. Anatomical responses of root tips to boron deficiency. III. Effect of boron deficiency on sub-cellular structure of root tips, particularly on morphology of cell wall and its related organelles. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 1976;22:53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Küster E (1958) Plasmoptyse. In LV Heilbrunn, F Weber, eds, Protoplasmotologia, Vol II C 7b. Springer-Verlag, Vienna, pp 1–33

- Loomis WD, Durst RW (1991) Boron and cell walls. In DD Randall, DG Blevins, CD Miles, eds, Current Topics in Plant Biochemistry and Physiology, Vol 10. University of Missouri, Columbia, pp 149–178

- Loomis WD, Durst RW. Chemistry and biology of boron. BioFactors. 1992;3:229–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mair JW, Day HG. Curcumin method for spectrophotometric determination of boron extracted from radiofrequency ashed animal tissues using 2-ethyl-1,3-hexanediol. Anal Chem. 1972;44:2015–2017. doi: 10.1021/ac60320a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschner H (1995) Mineral nutrition of higher plants, Ed 2. Academic Press, London, pp 379–396

- Matoh T. Boron in plant cell walls. Plant Soil. 1997;193:59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Matoh T, Ishigaki K, Mizutani M, Matsunaga W, Takabe K. Boron nutrition of cultured tobacco BY-2 cells. I. Requirement for and intracellular localization of boron and selection of cells that tolerate low levels of boron. Plant Cell Physiol. 1992;33:1135–1141. [Google Scholar]

- Matoh T, Ishigaki K, Ohno K, Azuma J. Isolation and characterization of a boron-polysaccharide complex from radish roots. Plant Cell Physiol. 1993;34:639–642. [Google Scholar]

- Matoh T, Kawaguchi S, Kobayashi M. Ubiquity of a borate-rhamnogalacturonan II complex in the cell walls of higher plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 1996;37:636–640. [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15:473–497. [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill M, Albersheim P, Darvill A. The pectic polysaccharides of primary cell walls. In: Dey PM, Harborne JB, editors. Methods in Plant Biochemistry, Vol 2: Carbohydrates. London: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 415–441. [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill MA, Warrenfeltz D, Kates K, Pellerin P, Doco T, Darvill AG, Albersheim P. Rhamnogalacturonan II, a pectic polysaccharide in the walls of growing plant cells, forms a dimer that is covalently cross-linked by a borate ester. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22923–22930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellerin P, Doco T, Vidal S, Williams P, Brillouet JM, O'Neill MA. Structural characterization of red wine rhamnogalacturonan II. Carbohydr Res. 1996;290:183–197. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(96)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmucker T. Über den Einfluβ von Borsäure auf Pflanzen, insbesondere keimende Pollenkörner. Planta. 1934;23:264–283. [Google Scholar]

- Seresinhe PSJW, Oertli JJ. Effects of boron on growth of tomato cell suspensions. Physiol Plant. 1991;81:31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Simon EW. Leakage from fruit cells into water. J Exp Bot. 1977;28:1147–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Slack CR, Whittington WJ. The role of boron in plant growth. III. The effects of differentiation and deficiency on radicle metabolism. J Exp Bot. 1964;15:495–514. [Google Scholar]

- Titel C, Woehlecke H, Afifi I, Ehwald R. Dynamics of limiting cell wall porosity in plant suspension cultures. Planta. 1997;203:320–326. [Google Scholar]

- Torssell K. Chemistry of arylboric acids. VI. Effects of arylboric acids on wheat roots and the role of boron in plants. Physiol Plant. 1956;9:652–664. [Google Scholar]

- Woehlecke H, Ehwald R. Characterization of size-permeation limits of cell walls and porous separation materials by high-performance size-exclusion chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1995;708:263–271. [Google Scholar]