Abstract

The role of protein flexibility in enzyme-catalyzed activation of chemical bonds is an evolving perspective in enzymology. Here we examine the role of protein motions in the hydride transfer reaction catalyzed by thymidylate synthase (TSase). Being remote from the chemical reaction site, the Y209W mutation of E. coli TSase significantly reduces the protein activity, despite the remarkable similarity between the crystal structures of the wild type and mutant enzymes with ligands representing their Michaelis complexes. The most conspicuous difference between those two crystal structures is in the anisotropic B-factors, which indicates disruption of the correlated atomic vibrations of protein residues in the mutant. This dynamically altered mutant allows a variety of small thiols to compete for the reaction intermediate that precedes the hydride transfer, indicating disruption of motions that preorganize the protein environment for this chemical step. Although the mutation causes higher enthalpy of activation of the hydride transfer, it only shows a small effect on the temperature-dependence of the intrinsic KIE, suggesting marginal changes in the geometry and dynamics of the H-donor and acceptor at the tunneling ready state. These observations suggest that that the mutation disrupts the concerted motions that bring the H-donor and acceptor together during the pre- and re-organization of the protein environment. The integrated structural and kinetic data allow us to probe the impact of protein motions on different timescales on the hydride transfer reaction within a complex enzymatic mechanism.

Keywords: Enzyme Dynamics, Enzyme Kinetics, Hydride Transfer, Marcus-like Models, Quantum Mechanical Tunneling, Kinetic Isotope Effect, X-ray Crystallography, Thymidylate Synthase

Introduction

Enzyme catalysis has been a focus of biochemistry research due to its importance in multiple disciplines such as life science, clinical research, and bioengineering. While the views for enzyme-substrate interaction have developed from Fischer’s “lock-and-key” model to Koshland’s “induced fit” model, Pauling’s transition state (TS) stabilization theory remains to be the most recognized principle for the chemical rate enhancement by enzymes. In the past few decades, the advanced experimental and computational techniques unraveled structural and dynamic features of numerous enzymes, allowing researchers to seek for the physical origin of “TS stabilization”. This investigation has led to an emerging hypothesis that extends the “induced fit” model and proposes that motions of protein, solvent, and substrates are an important component in a full description of enzyme-catalyzed reactions. Although immense work has examined this hypothesis, it has been most challenging to experimentally illustrate the impacts of protein motions at various timescales on a chemical bond activation step within a complex enzymatic mechanism.

For the examination of enzyme-catalyzed H-transfer reactions, a useful technique is the temperature dependence of kinetic isotope effects (KIEs).1–14 The analysis of the temperature dependence (or independence) of KIEs has stimulated the development of various phenomenological models, often summarized as the Marcus-like model (or environmentally-coupled tunneling, protein-promoting vibrations, vibrationally-enhanced tunneling, etc.).2,10,11,13–21 We have discussed this model in previous publications,11,14,22–26 and Figure S1 in the Supporting Information (SI) provides a brief description for the reader’s reference. This model designates three categories of protein motions that contribute to an enzymatic H-transfer. First, conformational fluctuations of the protein create a favorable environment for formation of the “reactive complexes” for the chemical step. This effect has been previously addressed as “preorganization”,10,27–30 and occurs on the second to submillisecond timescales.31 At this ensemble of reactive complexes, faster motions of protein, solvent, and ligands (e.g. on the nanosecond to picosecond timescales) constitute the “reorganization” of the active site that assists the structural changes in the substrates going from the reactant state to the tunneling ready state (TRS). At the TRS, the fluctuation of donor-acceptor distance (DAD) affects the H-tunneling probability (Figure S1). While the DAD fluctuation at TRS determines the magnitude and temperature dependence of the intrinsic KIE, pre- and re-organization affects the rate of the H-transfer and thus the “kinetic commitment” factor in the experimental exposure of KIEs.32,33 Previous experiments have found temperature-independent KIEs on H-transfer reactions in various wild type (WT) enzymes. These observations suggest the pre- and re-organization of the active site allows the system to reach a well-defined TRS for the H-transfer, which is characterized by a short and narrow DAD distribution.10,21,22,26,34,35

In this work we examine the relationship between structure, motions, and reactivity in the enzyme thymidylate synthase (TSase, EC 2.1.1.45) from E. coli. This enzyme catalyzes the last step of de novo synthesis of 2′-deoxythymidine-5′-monophosphate (dTMP) by reductive methylation of 2′-deoxyuridine-5′-monophosphate (dUMP), using (6R)-N5,N10-methylene-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrofolate (CH2H4folate) as a cofactor (Scheme 1).36 Since dTMP is one of the four DNA nucleotides, TSase is medicinally important as a common target for many antibiotic and chemotherapeutic drugs (e.g. Tomudex and 5-fluorouracil). In addition, the large collection of structural and kinetic data of TSase suggested that certain protein residues move synergistically during the catalytic cascade.37,38 These findings have initiated in-depth examinations of its molecular mechanisms by both experimentalists and theoreticians.23,39–47 Our previous studies found a temperature-independent KIE on the hydride transfer of WT ecTSase,39 suggesting the enzyme has evolved to bring the H-donor and acceptor to a well reorganized TRS. This interpretation has been supported by recent quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) calculations.44–47

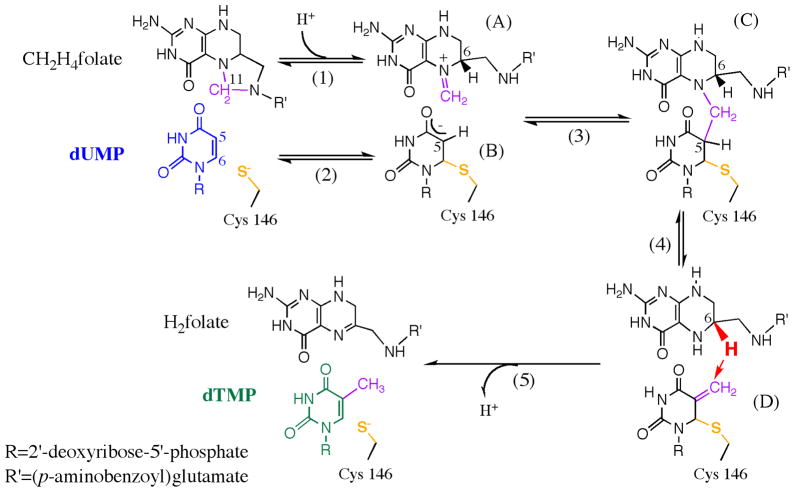

Scheme 1.

The proposed mechanism for thymidylate synthase (adapted from Ref 23 with permission from ACS). This reaction involves a series of chemical conversions (1–5) with several intermediates (A–D). All the chemical transformations happen at the “chemical reaction site” near the C146 residue (yellow), which forms the only covalent bond between the protein and the substrate during the catalytic turnover.

Here we employ both X-ray crystallography and kinetic measurements to study the impacts of protein motions at various timescales on the hydride transfer reaction. A highly conserved tyrosine residue (Y209 in ecTSase) forms one of only two H-bonds with the ribose ring of dUMP, which is remote from the chemical reaction site in ecTSase (Scheme 1). The crystal structures of the WT and Y209W ternary complexes with dUMP and an analogue of the cofactor, CB3717 (PDB IDs 2G8O and 2G8M, respectively), closely overlapped at a resolution of 1.30 Å.41 The most conspicuous difference between those two structures was in their anisotropic B factors, which revealed that the atomic vibrations of active site residues are highly correlated in the WT but not in the mutant crystals. This analysis indicated a dynamic effect48 that may account for the significantly reduced activity.41 However, the kinetic experiments preformed in Ref 41 did not identify which specific catalyzed step(s) is/are affected by the mutation. The current study extends the examination of the structural and kinetic properties of this mutant, and compares the temperature dependence of KIEs on the WT- and Y209W-catalyzed hydride transfer reactions. The correlation between the structural and kinetic data allows us to distinguish the mutational effects on protein motions at various timescales that influence the hydride transfer reaction and other catalytic steps.

Results and Discussions

Trapped Reaction Intermediate (Complex D)—Impaired “Preorganization”

Previous studies of Y209W employed β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME) to preserve a reducing environment in the reaction mixture. Our experiments under the same conditions yielded a new peak in the HPLC analysis of the reaction mixture (Figure S2). To investigate the origin of the new peak, we exploited radiolabeled reactants to study this side reaction. When [2-14C]dUMP and [6R-3H]CH2H4folate were used, the new byproduct contained 14C but no 3H radioactivity; and when non-radioactive dUMP and [11-14C]CH2H4folate were used, it contained 14C radioactivity. This indicates that the by-product is formed after the methylene transfer (step 4 in Scheme 1) but before the hydride transfer (step 5). Replacing β-ME with dithiothreitol (DTT) shifted the elution time of the new peak on the HPLC chromatograph (Table S2), indicating the by-product contained the thiol reagent. LC-MS analyses of the samples revealed that the molecular weight of the material was 397 or 473 when β-ME or DTT was used, respectively, which agree with the structures of 5-(2-hydroxyethyl)thiomethyl-dUMP (HETM-dUMP) and the corresponding DTT-derivative (Scheme 2). These observations suggest the by-products are formed by nucleophilic attack of the thiols at C7 of the exocyclic intermediate (Complex D in Scheme 1). This finding indicates that both β-ME and DTT can diffuse into the active site of Y209W and compete with the hydride donor for the hydride acceptor.

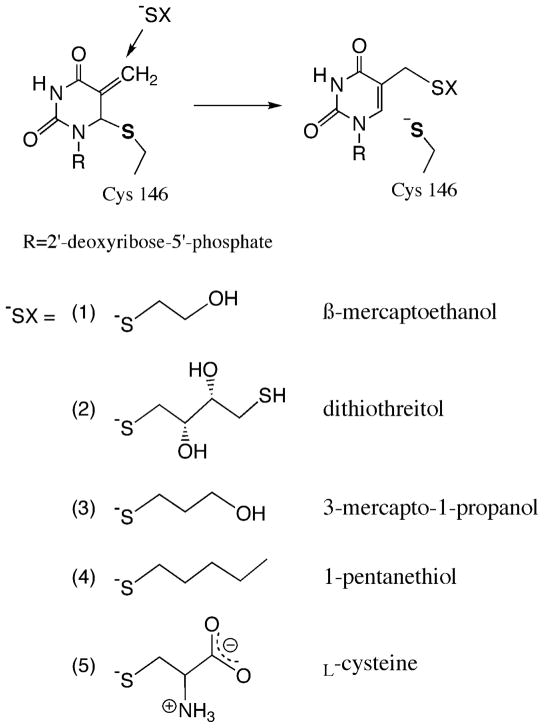

Scheme 2.

A variety of thiols (−SX) were tested as potential reagents to trap the exocyclic intermediate (Complex D in Scheme 1) in Y209W ecTSase-catalyzed reaction. This reaction directly competes with the hydride transfer step (step 5 in Scheme 1).

In order to evaluate the integrity of the active site of Y209W, we used a few other thiols of different sizes (Scheme 2) to compare their ability to access the ternary complex prior to the hydride transfer (Table 1). The results suggest that this ability is influenced by the size, hydrophilicity, polarity and flexibility in the structure of the thiol reagent. Particularly, the smallest reagent β-ME is the most favorable thiol to trap the intermediate. DTT traps almost equal amount of the intermediate with β-ME despite its larger molecular size than all other thiols, probably owing to extra hydrophilic groups in its structure that form favorable interactions with the active site environment. L-cysteine does not trap the intermediate at a detectable level, probably due to the strong polarity and rigidity in its structure that hinder its ability to diffuse into the active site.

Table 1.

Competitive formation of dTMP and the exocyclic intermediate trapped by different thiol reagents (trapped intermediate, TI) after 150 min incubation with Y209W at 25 °C. The percentage of TI in the products (%TI) reflects how easy each thiol diffuses into the active site to compete with the hydride transfer (step 5 in Scheme 1). The structure of each thiol is shown in Scheme 2.

| Thiol Reagents | %TI in products |

|---|---|

| 1. β-mercaptoethanol | 73% |

| 2. dithiolthreitol | 70% |

| 3. 3-mercapto-1-propanol | 59% |

| 4. 1-pentanethiol | 8% |

| 5. L-Cysteine | 0% |

Prior to the current study, only mutations close to the reaction site, i.e., on residues W82 and V316 (C-terminus) in L. Casei TSase (equivalent to residues W80 and I264 in ecTSase) have been reported to produce HETM-dUMP.49–51 W80 interacts with L143 and orients the latter to seal the active site cavity, and I264 interacts with the cofactor and is crucial for the ternary complex formation.37,38,40 Being farther from the hydride transfer site, the effect of Y209 on the solvent-accessibility of the exocyclic intermediate is not trivial. However, DTT can trap 70% of the exocyclic intermediate in Y209W but only an insignificant amount in W80M,40 suggesting that the reactive complex prior to the hydride transfer is less stable in the former. The formation of thiol-trapped intermediates suggest that the Y209W mutation deteriorates the ability of the enzyme to preorganize the active site for the hydride transfer, which significantly reduces the hydride transfer rate and thus the overall activity of the protein.

Steady-State Kinetics and Activation Parameters

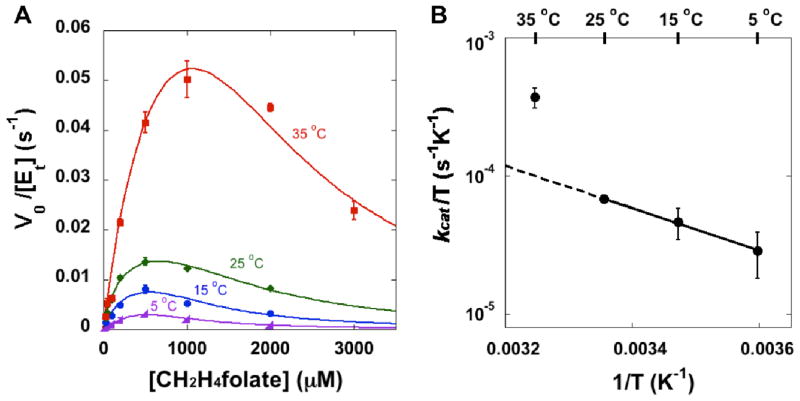

Due to the formation of HETM-dUMP, the presence of β-ME in the previous experiments41 has distorted the measured kinetic data of Y209W. Thus, we employed a non-thiol reducing agent, tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP),52 to ensure accurate measurements of the kinetic parameters of Y209W. Similar to the WT TSase,39 the activity of Y209W is inhibited by high concentrations of the cofactor CH2H4folate (Figure 1). The concentration of the substrate dUMP was kept constant close to saturation, and the data at each temperature were fit to the non-linear Michaelis-Menten equation with substrate inhibition (Figure 1A):39,53

Figure 1.

(A) Steady-state initial velocities of Y209W ecTSase vs. the concentration of CH2H4folate at 200 μM dUMP. At each temperature, the data were fit to Eq. 1 by least-squares nonlinear regression. For clarity purpose, this figure only shows the average with standard deviation for each data point, although all the measurements (at least triplicates for each point) were used in the nonlinear regression for each temperature. (B) The Eyring plot of kcat is in accordance with a change in the rate-limiting step above 25 °C (see text).

| (1) |

where [E]t is the total enzyme concentration; [S] is the concentration of CH2H4folate; and are the Michaelis constant and the inhibition constant of CH2H4folate, respectively. We also measured the Michaelis constant of dUMP ( ) at 25 °C (Figure S3).

Table 2 compares the kinetic parameters of the WT and Y209W TSase with β-ME or with TCEP at 25 °C. In contrast to our previous study of Y209W with β-ME,41 the data with TCEP indicate a larger effect on than on (the last column of Table 2). This discrepancy probably arises from the presence of β-ME in the previous experiment, which complicated the observed kinetics of Y209W as discussed earlier. The new observation agrees with previous findings for other Y209 mutants (F, M, and A),41 and suggests that although Y209 only forms H-bond with dUMP, mutations on this residue lead to a non-local effect on the interactions with CH2H4folate. Based on our new kinetic data, the Y209W mutation causes about 500-fold decrease in kcat, and more than 2000-fold and 7000-fold decrease in kcat/Km’s for dUMP and CH2H4folate, respectively. The values of , and at different temperatures are summarized in Table S3. The activation parameters of the initial velocities are summarized in Table 3. Compared with the WT enzyme, the Y209W mutation mainly affects ΔH‡ of kcat in the lower temperature range (5–25 °C, see Figure 1B and Table 3). The temperature dependence of kcat changes above 25 °C (i.e., kcat at 35 °C is higher than the extrapolation from the lower temperature range), which agrees with the change in the rate-limiting step revealed by the KIE experiment below.

Table 2.

Steady state kinetic parameters of the WT and Y209W ecTSase at 25 °C. The value in the parenthesis below each number is the magnitude of that value relative to the corresponding WT parameter.

| TSase | kcat (s−1) |

|

|

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT w/β-MEa | 8.8 (1) | 4.1 ± 0.4 (1) | 13.6 ± 0.2 (1) | 0.30 (1) | |||

| Y209W w/β-MEa | 0.05 ± 0.01 (0.005) | 118 ± 40 (28.8) | 172 ± 26 (12.6) | 0.69 (2.3) | |||

| Y209W w/TCEP | 0.020 ± 0.001 (0.002) | 19 ± 2b (4.6) | 214 ± 27 (15.7) | 0.089 (0.30) |

Data from Ref 41. A comparison of WT activity with β-ME and with TCEP found no difference.

Details shown in SI.

Table 3.

Activation parameters for kcat of WT and Y209W ecTSase.

| TSase | temperature range | ΔH‡ kcal/mol | TΔS‡ at 25 °C kcal/mol | ΔG‡ kcal/mol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 5–35 °C | 3.4 ± 0.2 | −12.8 ± 0.2 | 16.2 ± 0.4 |

| Y209W | 5–25 °C | 7.0 ± 0.3 | −12.8 ± 0.4 | 19.8 ± 0.7 |

| 25–35 °C | lower limit: ca. 30 | lower limit: ca. 11 | N.D. |

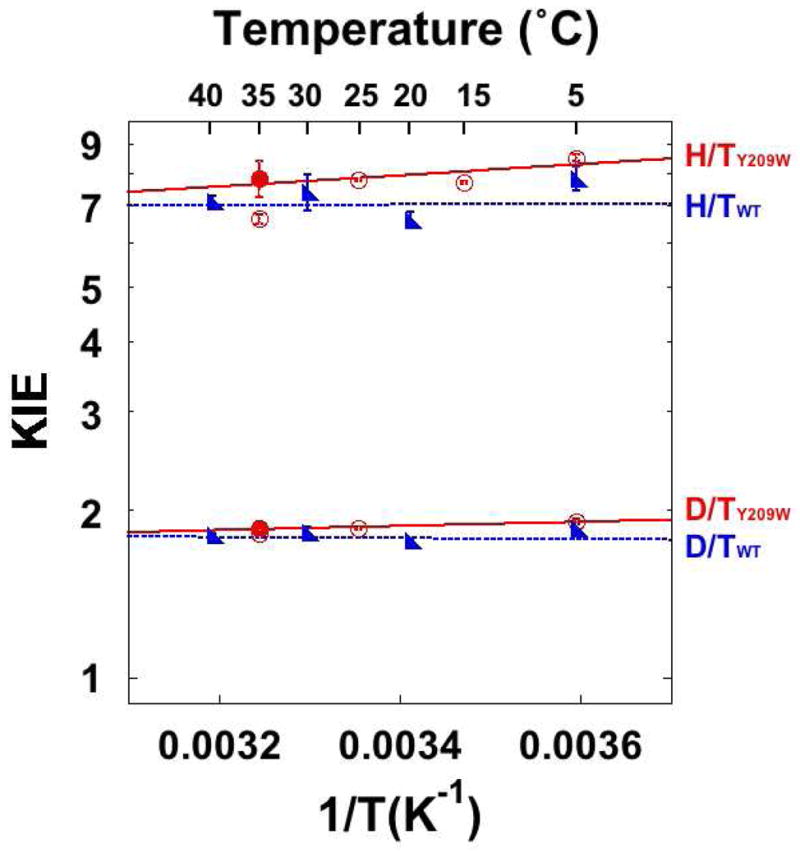

KIE on the Hydride Transfer Step – Effects on the “Reorganization” and TRS

We used the competitive H/T and D/T method11,24,32,33 to measure the H/T and D/T KIEs on the second order rate constant, kcat/KM with Y209W in 5–35 °C. The observed KIEs follow the Swain-Schaad relationship at 5 and 25 °C (Table S4), indicating that hydride transfer is rate limiting in the 5–25 °C temperature range, and the intrinsic KIEs are the same with the observed values at each temperature.11,24,32,33 Thus, the higher ΔH‡ of kcat (vs. WT TSase) in this temperature range suggests the Y209W mutation increases the reorganization energy for the hydride transfer.10,27–30 At 35 °C, the observed KIEs do not follow the Swain-Schaad relationship, and we used the Northrop method to extract the intrinsic KIEs from the observed values.32,33 The observed KIEs being smaller than their intrinsic values indicates that the hydride transfer is not rate limiting at that temperature due to kinetic complexity.11,24,32,33 These data corroborates the steady state kinetic data in the previous section that suggested a change in the kinetics between 25 °C and 35 °C. Since hydride transfer is not rate limiting for Y209W at 35 °C, the significant increase in both ΔH‡ and ΔS‡ of kcat at this temperature (Table 3) suggests that the mutation also affects other kinetic steps during the catalytic turnover.

Figure 2 shows the temperature dependence of intrinsic KIEs on the WT- and Y209W-catalyzed hydride transfers, and the observed KIEs for the mutant at 35 °C. The intrinsic KIEs were fit to the Arrhenius equation:

| (2) |

where the subscripts L and T denote the light isotope (H or D) and the heavy isotope (T) of hydrogen, respectively; k is the microscopic rate constant of the isotopic sensitive step (the hydride transfer step in this case), and ΔEa is the difference in the activation energies of that microscopic step between the light and heavy isotopes (ΔEa = EaL − EaT); AL/AT is the isotope effect on the pre-exponential Arrhenius parameter; R is the gas constant and T is the absolute temperature. Table 4 summarizes the H/T isotope effects on the Arrhenius parameters of both the WT- and Y209W-catalyzed hydride transfers (H/T, D/T, or H/D isotope effects refer to the same effect and follow the same trend).

Figure 2.

KIEs on the hydride transfers catalyzed by the WT (blue)39 and Y209W (red) ecTSase. The lines represent the least-squares nonlinear regression of the intrinsic KIEs to Eq. 2. The empty circles represent the observed KIEs, and filled circles represent the intrinsic KIEs when different from the observed, i.e. at 35 °C.

Table 4.

Isotope effects on Arrhenius parameters of the hydride transfers catalyzed by the WT and Y209W ecTSase.

Compared with the WT enzyme, the KIE on the hydride transfer of Y209W is more temperature-dependent with slightly larger magnitude in the 5–35 °C temperature range, leading to a smaller isotope effect on the pre-exponential parameter (AL/AT). However, AH/AT is still above the semi-classical limit (Table 4), suggesting that Y209W-catalyzed hydride transfer also occurs predominantly via quantum mechanical tunneling.11,14,24,58 Based on the Marcus-like models, these observations suggest that although the mutation is remote from the reaction site, the altered structural and dynamic properties of the mutant slightly change the DAD distribution at the TRS. In contrast, although the active site mutation W80M also produces HETM-dUMP, it shows no effect on the hydride transfer KIE.39 This further suggests the Y209 residue is connected to the hydride transfer site through a long range of interactions that are important for the hydride transfer.

Dynamic Effects of the Y209W mutation –Structural and Kinetic Evidence United

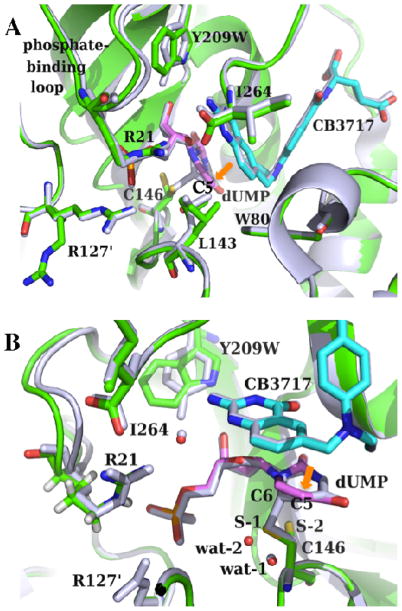

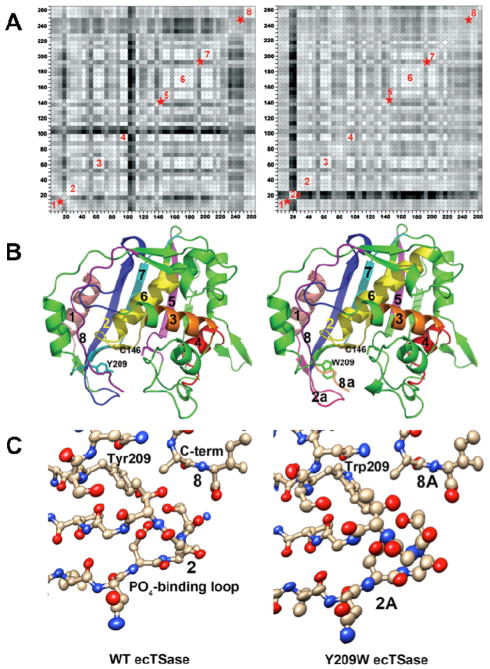

To elucidate the structural origin of the observed kinetic effects presented above, we carefully investigated the previously published electron density maps of the WT and Y209W ternary complexes (PDB IDs 2G8O and 4GEV, Figure 3),41 and performed new refinement of the latter. Here we only focus on new perspectives on the structural data in the context of observed kinetics in the current study. For a complete discussion on the crystal structures of various Y209 mutants, we would refer the reader to Ref 41.

Figure 3.

(A) Crystal structures of the ternary complexes of the WT (gray; PDB ID 2G8O) and Y209W (green; PDB ID 4GEV) ecTSase with dUMP (magenta) and CB3717 (cyan) are remarkably similar. The mutant shows two conformations for each of the residues R127′, L143, and C146. The mutation also causes interesting dynamic effect including the shift-away and increased mobility of the phosphate-binding loop, and the less correlated atomic vibrations of protein residues and ligands. All the catalyzed chemical bond activations happen around the C5 of dUMP (orange arrow). (B) A closer view of the active site. The additional conformation of C146 (S-2) in Y209W cannot form a covalent bond with dUMP, which is accompanied by the displacement of a nearby water molecule (from wat-1 to wat-2). R21 on this phosphate-binding loop also forms H-bonds with both I264 and the cofactor (through a water molecule).

Our previous studies showed that the crystal structure of the Y209W-dUMP-CB3717 complex is remarkably similar to the WT ternary complex with the same ligands (Figure 3). The difference electron density map of those two structures suggests that several residues exist in two conformations in Y209W, including R127′ (R127 from the other subunit of the protein), L143, and C146. The C146 residue is the active site sulfhydryl that nucleophilically attacks the C6 position of dUMP to initiate the catalyzed reaction (Scheme 1), and its additional conformation in Y209W cannot form this important covalent bond with dUMP (Figure 3B). The additional conformation of R127′ places its side chain away from the active site, which could allow the reactive thiols to diffuse into the active site to access the reaction intermediate. A previous study with W80G proposed two mechanisms for the formation of HETM-dUMP:51 (1) the mutation causes premature release of H4folate, allowing β-ME to diffuse into the active site and react with the intermediate; or (2) the active site of the W80G mutant is large enough to accommodate β-ME in addition to H4folate and the dUMP exocyclic intermediate. The W80G-dUMP-CB3717 crystal structure showed that the L143 side chain is exclusively in a conformation that impinges on the space occupied by the W80 side chain in WT TSase, which exposes the C7 of the exocyclic intermediate to bulk solvent.51 In contrast, the alternate conformation of L143 in Y209W is similar to its conformation in the WT enzyme, and is only occupied 30% of the time (Figure 3A). Although the alternate conformation of R127′ expands the active site cavity of Y209W, the residues around the hydride transfer site almost perfectly overlap with their conformations in the WT enzyme, which would not allow coexistence of a thiol and H4folate around C7 of the exocyclic intermediate. Therefore, it is more probable that the Y209W mutation causes premature release of the H4folate (i.e. hydride source), after which the reactive thiol can attack C7 of the exocyclic intermediate (i.e. hydride acceptor). Regardless of the exact mechanism of thiol attacking, the additional conformations of those three residues agree with our kinetic data that suggested a decreased fraction of the reactive complex, i.e. deteriorated “preorganization”, for the hydride transfer in Y209W.

The other observable difference in the Y209W ternary complex is that the dUMP phosphate-binding loop (residues 19–25 in ecTSase) shifts 1.0 ± 0.2 Å away from the active site, which is accompanied by higher normalized isotropic B factors in both this loop and dUMP (Figure 4).41 This observation indicates that both the substrate and the phosphate-binding loop are more mobile in the Y209W mutant. Crystal structures of the WT TSase suggested the phosphate-binding loop progressively closes towards the active site and becomes more rigid as the substrate and cofactor bind to the enzyme.37 Particularly, the highly conserved R21 residue in this loop not only forms H-bond with the phosphate group of dUMP, but also interact with both I264 and L143 (Figure 3). Consequently, the mutational effect on the location and mobility of this loop can propagate to the opposite wall of the active site cavity, leading to a “global” impact on the active site. Analysis of the anisotropic B factors revealed that in the WT TSase-dUMP-CB3717 complex, the atomic vibrations of active site residues are highly correlated with each other and, to a less extent, with the ligands, suggesting the protein residues can move concertedly (i.e. rigid-body vibrations) during the structural changes in the ligands.41 In contrast, the atomic vibrations in the Y209W-dUMP-CB3717 complex are much less correlated in several protein segments including the phosphate-binding loop, the C terminus, and the loop containing L143 and C146 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

(A) Plots showing correlations of anisotropic B-factor displacements between ecTSase atom pairs identified by the (x,y) grid coordinates of the plot (reproduced from Ref 41 with permission form ACS). The left plot is for WT ecTSase and the right plot is for Y209W. Grid points are shaded from white to black with white representing highest correlation, where degree of correlation is determined by similarity of projections of anisotropic displacements along the interatomic vector.59 Blocks of light colored squares along the diagonals of the plots indicate protein segments that vibrate as rigid bodies. Eight such segments are labeled in the plots, and red stars indicate segments where rigid body movement appears to have been disrupted by the mutation. Segment 2a in the Y209W plot is the phosphate-binding loop, whose vibrations are no longer correlated with the rest of the proteins segments. (B) Ribbon plots of WT ecTSase (left) and Y209W ecTSase (right). Segments labeled in (A) are labeled and colored. The catalytic cysteine and the mutated residue are shown as sticks. (C) Plot of the thermal ellipsoids of the phosphate-binding loop for WT (left) and Y209W ecTSase (right). This loop shifts to close the active site cavity during binding of the substrate and cofactor, and it has a key role in orienting the ligands and shielding the cavity from bulk solvent. R21 in this loop makes hydrogen bonds to the phosphate moiety of dUMP and to the protein C-terminus. The thermal ellipsoids are derived from the refined anisotropic B-factors of the structures and the radii of the ellipsoids are proportional to the root-mean-square displacements from the atom positions (see Experimental Details). The B-factors for the loop are larger in the mutant structure, as seen by the larger volumes of the ellipsoids. The thermal vibrations of atoms in the loop are also less well correlated with each other in the mutant, as evidenced by more random orientations of the long axes of the ellipsoids. In addition, the thermal vibrations of the atoms in the loop are no longer correlated with those of other protein segments lining the active site cavity, such as the segments containing S210 and the mutated Y209 or the C-terminal segment. The phosphate-binding loops and C-terminal residues are labeled with the segment numbers from the plots in (A).

Taken together, our structural and kinetic data indicate the Y209W mutation impairs the hydride transfer by affecting both the conformational fluctuations of specific active site residues, and the rigid-body vibrations of several protein segments that align the active site cavity. These altered protein motions are likely to occur at different timescales and have different activation parameters, which can explain the curvature in the Eyring plot of kcat in Y209W. The Y209W mutation perturbs the location and mobility of the phosphate-binding loop, where R21 propagates these effects to the C146-containing loop and the C-terminus that are closer to the hydride transfer reaction site. This long range of interactions can explain the unusual kinetics observed in Y209W, such as the reaction intermediate trapped by thiols, and a larger increase in than in . Furthermore, the rigid-body vibrations of the protein segments in the WT TSase ternary complex have very small amplitude (ca. 0.1 Å), indicating very high frequency that is on the timescale (picosecond) of the proposed reorganization motions in the Marcus-like model (Figure S1). Therefore, those rigid-body vibrations may contribute to the heavy atom reorganization that “optimize” the TRS for the hydride transfer in the WT TSase. The disruption of those vibrations in the Y209W mutant suggests defective heavy atom reorganization that generates a slightly different TRS, where the DADs are longer and/or the DAD distribution is wider, leading to marginally temperature dependent KIEs with larger magnitude (Figure 2 and Table 4).

Conclusions

Whether and how enzyme motions contribute to chemical bond activations is an important contemporary question in enzymology. Mutations remote from the chemical reaction site are of particular interest in addressing this question, since their effect usually requires structural and dynamic perturbations through a long range of interactions in the protein-ligands complex. A “dynamic network of coupled motions” has been proposed for dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) based on NMR relaxation experiments, genomic analysis, and QM/MM calculations.60–63 This proposal was substantiated by a couple of remote mutations that altered the temperature dependence of the hydride transfer KIE.64 Recent studies also reported several remote mutations that affected the chemical bond activations catalyzed by human purine nucleoside phosphorylase65,66 and soybean lipoxygenase-167. The current study integrates kinetic data with high-resolution crystal structures and anisotropic B-factors to analyze the effects of protein motions on different aspects (e.g. pre- and re-organization, and H-tunneling at the TRS) of a C-H→C transfer in a complex catalytic cascade. Our experiments with various thiols trapped the reaction intermediate prior to the hydride transfer in a remote mutant of ecTSase, Y209W. This suggests the mutation deteriorates the protein’s ability to preorganize the active site for the hydride transfer, which is further supported by additional conformations of several active site residues in its crystal structure. The poorly preorganized protein environment causes higher penalty of reorganization energy for the hydride transfer, as revealed by our steady state and KIE experiments. Some rigid-body vibrations in the WT crystal structure are lost in the mutant, suggesting potential contribution of these high frequency motions to the reorganization of protein environment for the hydride transfer. The marginal changes in the temperature dependence of hydride transfer KIE implicates slightly altered protein motions that modulate the DADs at the TRS. The remote location of the current mutation and the high structural similarity of its ternary complex to the WT enzyme spotlight the alteration of enzyme dynamics and their role in disrupting mechanistic and kinetic aspects, including the chemical conversion itself. These observations agree with our predictions from QM/MM calculations that some concerted protein motions in ecTSase can enhance the hydride transfer step.45–47 Future investigations on these concerted motions can examine the possibility of a “dynamic network” for TSase catalysis, and may provide new insights for rational drug designs that target TSase. In addition, these new findings provide another piece of the grand puzzle describing the relationship between motions and chemical reactivity in enzymes.

Experimental Section

Materials and Instruments

[2-14C] dUMP (specific radioactivity 53 Ci/mol) was from Moravek Biochemicals. [3H]NaBH4 (specific radioactivity 15 Ci/mmol) was from American Radiolabeled Chemicals. [2H]NaBH4 (> 99.5% D) was from Cambridge Isotopes. Unlabeled CH2H4folate was a generous gift from EPROVA (Switzerland). Ultima Gold liquid scintillation cocktails were from Packard Bioscience. Liquid scintillation vials were from Research Products International Corp. [2-3H]iPrOH and [2-2H]iPrOH were prepared by reduction of acetone with [3H]NaBH4 and [2H]NaBH4, respectively.68 Dihydrofolate (H2folate) was synthesized using Blakely’s method.69 The WT70 and Y209W41 ecTSase enzymes were expressed and purified following the previously published procedures. All other materials were purchased from Sigma. The steady state kinetic experiments were performed using a Hewlett-Packard Model 8452A diode-array spectrophotometer equipped with a temperature-controlled cuvette assembly. All the purifications and analytical separations were performed using an Agilent Technologies model 1100 HPLC system with a Supelco Discovery® C18 reverse phase column. The radioactive samples were analyzed using a Packard Flo-One radioactivity detector or a Liquid Scintillation Counter (LSC).

Experimental Details

Synthesis of [6R-xH]CH2H4folate for KIE Experiments

The [6R-xH]CH2H4folate was synthesized by adapting the published procedure71 with some modification. Briefly, the synthesis is a one-pot preparation that combines two enzymatic reactions and one chemical reaction: (1) alcohol dehydrogenase from thermoanarobium brockii (tbADH) catalyzes the reduction of NADP+ by [2-xH]iPrOH to produce [4R-xH]NADPH; (2) DHFR catalyzes the reduction of H2folate by [4R-xH]NADPH to produce [6S-xH]H2folate; (3) formaldehyde is added into the reaction mixture to trap [6S-xH]H2folate and form [6R-xH]CH2H4folate. The previous procedure used DTT in the reaction mixture, whereas we used glucose/glucose oxidase in situ oxygen scavenging system to maintain strict anaerobic conditions. The synthesized [6R-xH]CH2H4folate was purified by reverse phase HPLC (RP HPLC), lyophilized, and stored at −80 °C prior to use.

Formation of Thiol-trapped Intermediates

The final reaction mixtures for the comparison studies (Table 1) contained 100 μM dUMP, 200 μM CH2H4folate, 2 mM TCEP, 50 mM MgCl2 and 25 mM thiol reagent in 100 mM tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris)/HCl buffer (pH 7.5). The reaction was initiated by adding Y209W ecTSase, and incubated for 150 min at 25 °C prior to HPLC analysis. We used [2-14C]dUMP to track the formation of both dTMP and the thio-trapped intermediate, of which the relative amounts were analyzed by HPLC separation followed by Flo-One radioactivity detector. The RP-HPLC separation method and the elution times for the compounds in the reaction mixture are provided in SI (Table S1 and Table S2).

Steady-State Kinetics

The steady state initial velocities were measured by following the increase of absorbance at 340 nm that indicates the conversion of CH2H4folate to H2folate (Δε340nm = 6.4 mM−1cm−1), using the published procedure for the WT enzyme39 with modification. The reaction mixture for the mutant contained 2 mM TCEP instead of 50 mM DTT to avoid intermediate trapping by the thiols. The kcat and Km of CH2H4folate were measured with 200 μM dUMP at 5, 15, 25, and 35 °C, and the Km of dUMP was measured with 50 μM CH2H4folate at 25 °C. The steady state kinetic data at each temperature were analyzed with the least squares nonlinear regression available in KaleidaGraph (Version 4.03). This analysis provided the steady state rate constants of the reaction at four different temperatures, which were fit to the Eyring equation (Eq. 3) to evaluate the activation parameters (Figure 1.B, Table 3). Although the activation parameters for 25–35 °C were only based on two data points, they provide a reliable qualitative comparison with data in the low temperature range.

| (3) |

Observed and intrinsic KIEs on the Hydride Transfer

The competitive method11,24,32,33 was used to measure the KIE on the hydride transfer step in the temperature range of 5–35 °C, following the procedure published for the WT enzyme39 with modification. For the same reasons described above, the reaction mixture for the mutant replaced DTT with 2 mM TCEP. The Northrop method was used to extract the intrinsic KIEs from the observed values.32,33

New Refinement of the Crystal Structure of Y209W-dUMP-CB3717 Complex

Difference density (Fo-Fc)αcalc maps, computed with refined coordinates of Y209W ecTSase,41 were examined for evidence of disorder that would allow solvent to access the active site. At low contour levels, alternate conformations could be identified for L143 and C146 in both active sites and for R127 in one of the active sites. Two conformations were fitted to density for these three residues, and a new water molecule near the dUMP of the most disordered active site was also built into density (Figure 4.B). Updated coordinates were refined in Phenix against a complete data set between 45.8Å and 1.3Å resolution using a maximum likelihood target function and anisotropic temperature factors for all non-hydrogen atoms. Occupancies for the two conformations of each disordered residue were refined with the constraint that they summed to 1.0. Refinement converged at R=12.79% and Rfree=15.24%. RMS deviations in bonds and angles were 0.009Å and 1.34°, respectively, and 99% of the residues had backbone (ϕ, ψ) angles in the most favored regions of the Ramachandran diagram. The clash score (number of steric overlaps > 4Å per 1000 atoms) was 3.92. Figures 3 and 4 illustrate the differences in the structures and dynamics of the WT and Y209W ternary enzyme complexes. Figure 3 and Figure 4B were generated by Pymol v1.5.0.4, and Figure 4C was generated by Chimera.72

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH GM065368 and NSF CHE-1149023 (AK), a fellowship from the Center for Bioprocessing and Biocatalysis at the University of Iowa (ZW), and GM51232 (RMS).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Descriptions of Marcus-like model for H-transfer reactions; HPLC separation of the reaction mixtures; steady state kinetic parameters and the observed and intrinsic KIE values at different temperatures; steady state initial velocities vs. dUMP concentrations. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

References

- 1.Gao J, Ma S, Major DT, Nam K, Pu J, Truhlar DG. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3188–3209. doi: 10.1021/cr050293k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammes-Schiffer S. Accounts Chem Res. 2006;39:93–100. doi: 10.1021/ar040199a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kohen A, Limbach H-H. Isotope Effects in Chemistry and Biology. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; Boca Raton, FL: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutcliffe MJ, Masgrau L, Roujeinikova A, Johannissen LO, Hothi P, Basran J, Ranaghan KE, Mulholland AJ, Leys D, Scrutton NS. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361:1375–1386. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pu J, Gao J, Truhlar DG. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3140–3169. doi: 10.1021/cr050308e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knapp MJ, Meyer M, Klinman JP. In: Hydrogen-Transfer Reactions. Hynes JT, Klinman JP, Limbach H-H, Schowen RL, editors. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2007. pp. 1241–1284. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu H, Warshel A. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:7852–7861. doi: 10.1021/jp070938f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quaye O, Gadda G. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;489:10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loveridge EJ, Allemann RK. Biochemistry. 2010;49:5390–5396. doi: 10.1021/bi100761x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagel ZD, Klinman JP. Chem Rev. 2010;110:PR41–PR67. doi: 10.1021/cr1001035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sen A, Kohen A. J Phys Org Chem. 2010;23:613–619. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glowacki DR, Harvey JN, Mulholland AJ. Nat Chem. 2012;4:169–176. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hay S, Scrutton NS. Nat Chem. 2012;4:161–168. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Z, Roston D, Kohen A. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2012;87:155–180. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-398312-1.00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borgis DC, Lee SY, Hynes JT. Chem Phys Lett. 1989;162:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuznetsov AM, Ulstrup J. Can J Chem. 1999;77:1085–1096. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcus RA. J Chem Phys. 2006;125:194504. doi: 10.1063/1.2372496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marcus RA. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:6643–6654. doi: 10.1021/jp071589s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartz SD, Schramm VL. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:551–558. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Truhlar DG. J Phys Org Chem. 2010;23:660–676. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pudney CR, Johannissen LO, Sutcliffe MJ, Hay S, Scrutton NS. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:11329–11335. doi: 10.1021/ja1048048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bandaria JN, Dutta S, Nydegger MW, Rock W, Kohen A, Cheatum CM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:17974–17979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912190107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Z, Kohen A. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:9820–9825. doi: 10.1021/ja103010b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohen A, Roston D, Stojkoviæ V, Wang Z. In: Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry. Meyers RA, editor. S1–S3. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; Chichester, UK: 2011. pp. 77–99. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roston D, Cheatum CM, Kohen A. Biochemistry. 2012;51:6860–6870. doi: 10.1021/bi300613e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stojkovic V, Perissinotti LL, Willmer D, Benkovic SJ, Kohen A. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:1738–1745. doi: 10.1021/ja209425w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warshel A. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27035–27038. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cannon WR, Benkovic SJ. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26257–26260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajagopalan PT, Benkovic SJ. Chem Rec. 2002;2:24–36. doi: 10.1002/tcr.10009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hammes-Schiffer S, Benkovic SJ. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:519–541. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Preorganization includes all the kinetic steps that lead to formation of the reactive complex. In the current context, it includes the lifetime of the intermediate prior to the H-transfer step, i.e. the conformational fluctuations that bring the H-donor to the vicinity of the H-acceptor.

- 32.Northrop DB. In: Enzyme Mechanism from Isotope Effects. Cook PF, editor. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1991. pp. 181–202. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cook PF, Cleland WW. Enzyme Kinetics and Mechanism. Garland Science; London; New York: 2007. pp. 253–324. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fan F, Gadda G. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17954–17961. doi: 10.1021/ja0560377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roston D, Kohen A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:9572–9577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000931107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carreras CW, Santi DV. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:721–762. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.003445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stroud RM, Finer-Moore JS. Biochemistry. 2003;42:239–247. doi: 10.1021/bi020598i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Finer-Moore JS, Santi DV, Stroud RM. Biochemistry. 2003;42:248–256. doi: 10.1021/bi020599a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Agrawal N, Hong B, Mihai C, Kohen A. Biochemistry. 2004;43:1998–2006. doi: 10.1021/bi036124g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hong B, Haddad M, Maley F, Jensen JH, Kohen A. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:5636–5637. doi: 10.1021/ja060196o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Newby Z, Lee TT, Morse RJ, Liu Y, Liu L, Venkatraman P, Santi DV, Finer-Moore JS, Stroud RM. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7415–7428. doi: 10.1021/bi060152s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hong B, Maley F, Kohen A. Biochemistry. 2007;46:14188–14197. doi: 10.1021/bi701363s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kanaan N, Martí S, Moliner V, Kohen A. Biochemistry. 2007;46:3704–3713. doi: 10.1021/bi061953y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kanaan N, Marti S, Moliner V, Kohen A. J Phys Chem A. 2009;113:2176–2182. doi: 10.1021/jp810548d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kanaan N, Roca M, Tunon I, Marti S, Moliner V. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:13593–13600. doi: 10.1021/jp1072457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kanaan N, Roca M, Tunon I, Marti S, Moliner V. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2010;12:11657–11664. doi: 10.1039/c003799k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kanaan N, Ferrer S, Marti S, Garcia-Viloca M, Kohen A, Moliner V. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:6692–6702. doi: 10.1021/ja1114369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Here we do not distinguish “dynamics” as nonequilibrium or nonstatistical dynamics. Thus, the “dynamic effect” simply means the influence of motions of the protein, solvent, and ligands.

- 49.Barrett JE, Lucero CM, Schultz PG. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:7965–7966. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Variath P, Liu Y, Lee TT, Stroud RM, Santi DV. Biochemistry. 2000;39:2429–2435. doi: 10.1021/bi991802d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fritz TA, Liu L, Finer-Moore JS, Stroud RM. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7021–7029. doi: 10.1021/bi012108c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cline DJ, Redding SE, Brohawn SG, Psathas JN, Schneider JP, Thorpe C. Biochemistry. 2004;43:15195–15203. doi: 10.1021/bi048329a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cook PF, Cleland WW. Enzyme Kinetics and Mechanism. Garland Science; London; New York: 2007. pp. 121–204. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stern MJ, Weston JRE. J Chem Phys. 1974;60:2803–2807. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stern MJ, Weston JRE. J Chem Phys. 1974;60:2808–2814. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stern MJ, Weston JRE. J Chem Phys. 1974;60:2815–2821. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Melander LCS, Saunders WH. Reaction Rates of Isotopic Molecules. R.E. Krieger Pub. Co; Malabar, Fla: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kohen A. In: Hydrogen-Transfer Reactions. Hynes JT, Klinman JP, Limbach H-H, Schowen RL, editors. Vol. 4. Wiley_VCH; Weinheim: 2007. pp. 1311–1340. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rosenfield RE, Trueblood KN, Dunitz JD. Acta Crystallogr A. 1978;34:828–829. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Agarwal PK, Billeter SR, Rajagopalan PT, Benkovic SJ, Hammes-Schiffer S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2794–2799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052005999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wong KF, Selzer T, Benkovic SJ, Hammes-Schiffer S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6807–6812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408343102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nashine VC, Hammes-Schiffer S, Benkovic SJ. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:644–651. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hammes GG, Benkovic SJ, Hammes-Schiffer S. Biochemistry. 2011;50:10422–10430. doi: 10.1021/bi201486f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang L, Goodey NM, Benkovic SJ, Kohen A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15753–15758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606976103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saen-Oon S, Ghanem M, Schramm VL, Schwartz SD. Biophys J. 2008;94:4078–4088. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.121913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ghanem M, Li L, Wing C, Schramm VL. Biochemistry. 2008;47:2559–2564. doi: 10.1021/bi702132e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Meyer MP, Tomchick DR, Klinman JP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:1146–1151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710643105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Agrawal N, Kohen A. Anal Biochem. 2003;322:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Blakley RL. Nature. 1960;188:231–232. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Changchien L-M, Garibian A, Frasca V, Lobo A, Maley GF, Maley F. Prot Expres Pur. 2000;19:265–270. doi: 10.1006/prep.2000.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Agrawal N, Mihai C, Kohen A. Anal Biochem. 2004;328:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.