Abstract

I have documented the shift in youth alcoholic beverage preference from beer to distilled spirits between 2001 and 2009.

I have assessed the role of distilled spirits industry marketing strategies to promote this shift using the Smirnoff brand marketing campaign as a case example.

I conclude with a discussion of the similarities in corporate tactics across consumer products with adverse public health impacts, the importance of studying corporate marketing and public relations practices, and the implications of those practices for public health.

THE ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGE market has experienced 2 dramatic shifts in the past 4 decades. Between 1970 and 1997, beer became the dominant beverage of choice, taking substantial market share from distilled spirits. This trend was precipitated by young consumers, who began choosing beer and wine over distilled spirits as they came of age. Distilled spirits became identified with older generations.

Market forecasters predicted the slow demise of the distilled spirits category, in part because of these shifting demographics. These projections proved to be premature. Beginning in the late 1990s, young people's beverage preferences began shifting again, beer's growth flattened, and the distilled spirits market grew rapidly, with most growth concentrated in particular brands of “white goods”—vodka, rum, and tequila.

What accounts for this change in fortunes for the distilled spirits industry? The short answer is youth marketing innovation. I have described this market transformation, focusing on the marketing strategies associated with the Smirnoff Vodka brand as a case study. I conclude by analyzing the public health implications of this transformation.

THE DECLINE OF THE DISTILLED SPIRITS MARKET

Distilled spirits were the alcoholic beverage of choice during Prohibition. After Repeal, beer and distilled spirits had approximately the same market share (based on absolute alcohol consumption), and the markets for both products grew rapidly for the next several decades.1 Beginning around 1970, however, an important shift occurred; beer sales kept increasing whereas distilled spirits began a steady, steep decline.2

Distillers faced 3 major hurdles in keeping pace with beer. At the end of Prohibition, distilled spirits were considered the most hazardous of the 3 types of beverages because of their high alcohol content and their link to organized crime and moonshining. Beer and wine were seen as beverages of moderation.3,4 To encourage consumers to shift their alcoholic beverage preferences, policymakers established 3 key policies:

Tax distilled spirits at much higher rates per unit of alcohol.

Make distilled spirits much less available by strictly limiting the types of retail outlets where they can be sold.

Allow beer and wine, but not distilled spirits, to advertise on electronic media including television and radio.

The electronic media ban was a voluntary agreement between distillers and electronic media stations instituted as a response to 9 congressional hearings between 1947 and 1958. The voluntary ban helped convince Congress not to pass a legislative ban.5

The beer industry exploited these regulatory advantages, increasing its share of the alcohol market at the expense of the distilled spirits industry. Philip Morris, the world's largest tobacco company at that time, bought Miller Beer and adapted its tobacco marketing strategies to the beer industry, transforming the beer market. Television advertising expenditures soared, youth-oriented advertisement copy became common, and Miller and Anheuser Busch, who came to dominate the beer market, became fierce competitors.6,7 During this same period, the population was shifting rapidly to the suburbs, spurring the proliferation of convenience stores. Beer and tobacco became key staples of these new retail outlets. Brewers also centralized the brewing process, establishing high-tech breweries that greatly reduced the per-unit cost of production. Beer prices dropped steadily relative to inflation.7

A June 1991 federal study documented the new dominance of beer in the youth market. Beer was by far the alcoholic beverage of choice among junior high and high school students who reported binge drinking; these individuals were averaging 13.3 servings of beer per week compared with only 1.2 servings of distilled spirits per week.8

Distillers could not compete effectively for the youth market in this policy climate. Unable to use the media most popular with young people, their products became increasingly identified with older and aging consumers and were not considered youth friendly because of their relatively harsh flavor. Convenience stores typically do not sell distilled spirits, so the gap between the number of beer and distilled spirits retailers grew. Distilled spirit prices were higher than were those of beer because of tax differentials.

Beer's advantage among underage drinkers had important financial implications for distillers because of the critical role underage drinking generally plays in the alcohol market. The average age of first use among youths younger than 21 years is 15.8 years, and those who begin drinking before age 15 years are significantly more likely to become heavy consumers and to experience a wide range of alcohol problems than are those who wait until age 21 years.9 According to a National Research Council/Institute of Medicine report, underage drinkers consume between 10% and 19% of the alcohol on the market (almost all of which is consumed in binge drinking episodes), producing between $10 and $20 billion in annual revenues.10 Underage drinkers’ increasing preference for beer, therefore, meant that distillers were losing revenues to beer in the short term and facing a shrinking market in the long term as underage drinkers became adults.

THE DISTILLERS RESPOND: THE SMIRNOFF BRAND CASE STUDY

In 1997, Grand Metropolitan and Guinness merged to form Diageo, a British-based multinational corporation. Diageo has been the largest distilled spirits producer in the world since that time. A top priority for the new company was to reverse the downward sales trend of its core brands in the United States.

The company's primary focus turned to its white distilled spirits brands, which did not have the harsh tastes associated with “brown” distilled spirits (whiskeys and bourbons) and gin.2,11 The white brands could be mixed with fruit flavors and sugar to create a beverage more akin to soft drinks. This was an important characteristic because during the previous 2 decades, soft drinks had become the most popular commercial beverage in the US market, capturing an increasing “stomach share” from alcoholic beverages, coffee, teas, milk, and tap water, particularly among young people.6 Other types of commercial beverage producers viewed soft drinks as competitors and sought ways to imitate their tastes and marketing strategies.

Diageo developed a sophisticated marketing strategy to reenergize its Smirnoff Vodka brand using 3 key components:

Develop a beverage that tasted like soft drinks.

Use the Smirnoff Vodka brand name but market the product as a malt beverage to compete effectively with beer in terms of price, availability, and advertising in electronic media.

Reorient Smirnoff Vodka itself as a young person's brand by adding new fruit flavors and using other marketing innovations.

Smirnoff Ice: The Transition Beverage

Diageo introduced Smirnoff Ice in 1999 and initiated an aggressive marketing program in 2000. The company claimed that it was a “flavored malt beverage” and therefore should be regulated as a beer because the production process started with beer. Both federal and state regulators accepted this representation. Diageo adopted marketing strategies associated with the beer industry. Public health groups, concerned that the product was designed for the youth market, used the term “alcopop” for Smirnoff Ice and other sweet, malt-based products because of their similarity to soda pop.12

Smirnoff Ice quickly became the dominant beverage in the alcopop category. It invested nearly $40 million in 2001 and $50 million in 2002 for advertising in measured media (television, radio, magazines, newspapers, and outdoor platforms), mostly television.2,13 Smirnoff Ice advertising shot up from 2% to 50% of all alcopop advertising between 2000 and 2001.

Diageo placed its Smirnoff Ice advertising in media venues with relatively large youth audiences. The Center for Alcohol Marketing and Youth (CAMY) conducted a series of studies documenting the extent to which alcohol advertising was placed in television programming with disproportionately youthful audiences (> 15% of the audience being aged 12–20 years, despite this age group comprising only 15% of the total viewing audience). For 2002, CAMY reported that Smirnoff Ice placed more than 1500 alcohol advertisements on television programming with disproportionately youthful audiences. A substantial number of the advertisements were on television shows with youth audiences of greater than 30%, violating the industry's own voluntary standard.14 In 2005, there were more than 1300 Smirnoff Ice and Smirnoff Twisted V alcopop television advertisements that violated the industry's 30% standard, placing it among the worst alcohol brands for overexposing youths.15 In 2007, CAMY reported that Smirnoff Ice was the brand with the highest number of television advertisements placed on programs that overexposed youths.16

Although beer remained the dominant type of alcohol advertised on television, Diageo avoided the voluntary ban on distilled spirits by advertising on electronic media and thereby competed with beer companies to reach youth audiences with its Smirnoff brand. Diageo spent approximately $45 million on electronic media advertising to launch Smirnoff Ice in 2002, for example; only the 4 most popular beer brands (Bud Light, Miller Lite, Budweiser, and Coors Light) had higher electronic media advertisement spending that year.17

Other alcopop producers followed Diageo's lead. Measured media advertising expenditure for all alcopop brands went from $27.5 million to $196.3 million between 2000 and 2002, significantly increasing the total amount of youth exposure to alcohol advertising and contributing to a rapid growth in consumption from 105.1 million gallons in 2000 to nearly 180.0 million gallons in 2002.2,14,18 Smirnoff Ice accounted for 68.0% of the increase, producing 52.0 million gallons in 2002. Between 2000 and 2002, Diageo increased its market share in the alcopop market from 0.6% to 29.0%.2

Young people, particularly girls, contributed substantially to alcopops’ surge in popularity. According to the 2009 federally funded Monitoring the Future survey, 9.5% of 8th graders, 19.0% of 10th graders, and 27.0% of 12th graders had consumed alcopops at least once in the past month, with girls’ rates substantially higher.19 Moreover, these figures underestimate the impact of alcopops as a transition beverage. When examining only youths who report regular alcohol consumption (defined as at least 1 drinking episode in the past 30 days), 64.0% of 8th graders reported regular use of alcopops.19 The use of alcopops among drinkers declines sharply with age, with only 24.0% of drinkers aged 29 to 30 years reporting regular consumption of alcopops.20 Alcopops are more popular than is beer among teenage girls even though alcopops constitute a mere 2% of the beer market.13,19

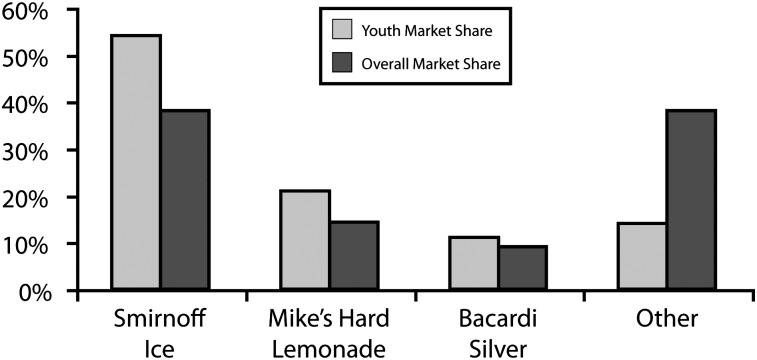

Diageo's marketing tactics contributed disproportionately to this youth appeal compared with tactics used by other alcopop producers. For example, Wolfson et al. conducted a multistate survey of alcopop use among 6800 youths in 2005 and found that Smirnoff Ice was the brand of choice for 54% of respondents who reported alcohol consumption—making it 2.5 times more popular than its nearest competitor and substantially more popular among youths than among the general population (Figure 1).21 Another study conducted in the San Francisco Bay area asked 6th, 7th, and 8th graders about their familiarity with various alcopop brands; it reported that Smirnoff Ice was 3 times more likely to be named than any of its competitors.22

FIGURE 1—

Alcopop brand preferences among underage drinkers.

Is Smirnoff Ice Properly Classified as Beer?

As noted in the previous section, a key to Diageo's marketing strategy was having alcopops classified as beer instead of distilled spirits under applicable federal and state laws. Without this classification, Smirnoff Ice would have been taxed at much higher rates and been unavailable in most convenience stores, and Diageo would not have been able to advertise the product on electronic media. To achieve this end, the company had to overcome a serious barrier: the malt base had an unpleasant, bitter taste.23 To address the taste problem, alcopop producers including Diageo developed a complex manufacturing process. According to a study conducted in 2003 by the US Department of Treasury's Alcohol and Tobacco Tax Trade Bureau (TTB),24 alcopop producers filtered the malt beverage base to remove most or all taste, odor, carbonation, and fermented alcohol. Either before or after this filtering process, most of the beer base was drained (typically 75% or more of the original liquid) and replaced with other liquids, including “flavoring” that contained distilled spirits. Until 2005, distilled spirits made up most (up to 99%) of the alcohol in alcopops.24 In 2005, the TTB required producers to limit the added distilled spirits to 50% of the total alcohol in the product.25 The TTB summarized its findings by stating that “flavored malt beverages exhibit little or no traditional beer or malt beverage character.”24(p14 293)

This production process puts into serious question whether alcopops are “beer” under federal and most state laws.12,26 The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, TTB's predecessor agency, held in 1996 that beer containing distilled spirits was properly classified as a distilled spirit under federal law.27 However, the holding was never enforced, and TTB reversed it in 2005 when it set the 50% limit, citing potential financial hardship for producers to justify its decision.12,25,26

The TTB action does not affect state laws, which in many cases appear to require that alcopops be regulated as distilled spirits, thus taking away the regulatory benefits that Diageo and other manufacturers are seeking.26 Four state attorneys general (in California, Connecticut, Maine, and Maryland) have taken action or issued letters or opinions concluding that alcopops should be regulated as distilled spirits in their states.28 In Nebraska, a court reversed the attorney general's opinion reaching the opposite conclusion, although the court's decision has since been appealed.29 In response, the industry has sponsored state legislation to redefine beer to include alcopops, succeeding in at least 8 states thus far.28 In short, regulating Smirnoff Ice and other alcopops as beer—a critical element of the marketing plan—appears to violate many state laws.26

Smirnoff Ice's Link to Smirnoff Vodka

The alcopops beverage category did not sustain the rapid growth it experienced between 2000 and 2002. Starting in 2003, sales slumped significantly and continued to decline through 2008.13 Smirnoff Ice sales were no exception; although its sales climbed through 2004, they dropped 36% between 2005 and 2008, according to the most recent data available.13 As with wine coolers in the 1980s, alcopops appear to have been something of a fad, gaining popularity when first introduced but then fading and reaching a plateau. They continue to be popular among young drinkers, however, and continue to play the transition role of introducing younger teenagers, particularly girls, to alcoholic beverages.19

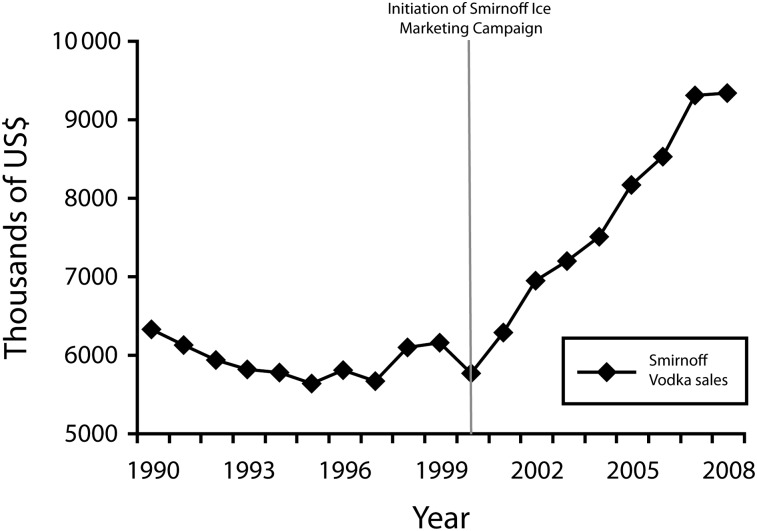

Unfortunately, data are not available to assess shifts in brand-level awareness, comprehension, and persuasion among young people. Nevertheless, an examination of sales and marketing data suggests that the drop in Smirnoff Ice sales may have been anticipated by Diageo and may have been part of a long-term strategy for reaching the youth market. As previously noted, Diageo used Smirnoff Ice to introduce the Smirnoff brand to young consumers, thereby overcoming the slide in Smirnoff Vodka sales. Available data suggest that Diageo appears to have achieved this goal; since the introduction of Smirnoff Ice in 2000, Smirnoff Vodka sales have experienced a steady increase in sales (61% between 2000 and 2008; Figure 2). This stands in sharp contrast to the previous decade, during which the brand experienced a 9% decline in sales.13

FIGURE 2—

Smirnoff Vodka sales: United States, 1990–2008.

Source. Impact Databank.13

Diageo coordinated the marketing strategies for Smirnoff Vodka and Smirnoff Ice to encourage the linking of the 2 products in the minds of consumers. It created numerous fruit-flavored Smirnoff Vodka Twist flavors that had similar tastes, containers, advertising, and flavorings as the Smirnoff Twisted V alcopop brands. Perhaps most significant, starting in 2003, Diageo began an aggressive television advertising campaign for Smirnoff Vodka as well as other Diageo brands. The distilled spirits industry had lifted its voluntary ban on television and radio advertising in 1996. This initially did not have much effect because network television stations continued their own voluntary ban. However, cable networks opened the airways to the industry, and television distilled spirits advertising subsequently underwent a rapid increase, from 1973 advertisements in 2001 to 62 776 advertisements in 2007, with Diageo playing a leading role.30

As with Smirnoff Ice, Diageo's placements of its Smirnoff Vodka television advertisements were often on programming with a disproportionate number of underage viewers. For 2005, CAMY reported that 11.8% of its advertising (338 advertisements total) was placed in shows with 30% or higher youth audiences, violating the industry's own voluntary advertising placement standard.15 No other vodka brand came close to this level of violation, and only 2 other distilled spirits brands had a higher number (one of which was Diageo's tequila brand, José Cuervo). CAMY rated Smirnoff Vodka television advertising among the 10 worst performing alcohol brands in 2007 in terms of overexposing youths. It was the only vodka brand on the list and 1 of only 3 distilled spirits brands included.16

Diageo's television advertising strategy was augmented with an aggressive push into the digital marketing arena. Creating interactive Web sites; positioning on social network sites such as Facebook, Internet games, YouTube videos, and viral marketing; and other strategies are now staples for Smirnoff and other Diageo brands, most notably Captain Morgan Rum.31 Diageo announced that in 2010, digital marketing will account for 21% of its marketing budget.32 This form of marketing is largely unregulated and has a high likelihood of reaching underage youths, who are frequent participants in these interactive marketing activities.31

A drinking game called “icing” illustrates the potential reach and impact of this type of marketing. Started at a fraternity, the game involves an “attacker” who hands a bottle of Smirnoff Ice to a friend who must drink it all at once unless he has a bottle in his possession. The game usually involves men and is a spoof of the sugary taste and female appeal of the beverage. It rapidly became a national phenomenon, gaining great notoriety on Web-based social networks and significant press coverage, apparently without any direct involvement by Diageo.33

Industry observers agree that these marketing efforts to reposition Smirnoff Vodka as a youth-oriented product appear to have been successful. In 2003, a commentary in Impact Magazine (a premier industry periodical) observed,

Diageo rolled out Smirnoff Ice in the US market … it suddenly put the once-stodgy Smirnoff name on the tips of millions of echo boomers’ tongues.34(p4)

(Echo boomers were born between 1977 and 1994, and most were underage at the time this quote was made.) Smirnoff was named the most powerful alcoholic beverage brand in 2010 by Intangible Business in its Power 100 report, citing Smirnoff's modern, cool image.35

The Smirnoff brand case study clearly highlights the importance of branding; different brands are marketed to reach distinct audiences. For example, Diageo's youth marketing strategy for Smirnoff contrasted sharply with its marketing strategies for its other vodkas and the vodkas of most competitors. Although the vodka category generally increased in the past 10 years, a large percentage of that increase is attributable to the Smirnoff brand.13

Distilled Spirits and the Youth Market Today

Diageo's and other distillers’ marketing innovations over the past decade have had a dramatic impact on the alcohol market. The Smirnoff example is not unique. For example, Diageo's Captain Morgan Rum and José Cuervo Tequila brands received similar marketing treatment and have experienced similar gains in sales. Barcardi Rum, Skyy Vodka, and Hennessy Cognac are among the other brands with notably innovative youth-oriented market strategies.

Distillers have reversed the trends and are now gaining on beer in terms of market share. Although beer remains the dominant beverage of choice among all drinkers, distilled spirits have experienced a 16% increase in per-capita alcohol consumption since 1999, whereas beer has shown a 2% decline. The gains have occurred almost exclusively among vodka, rum, and tequila brands, which together experienced a 56% increase in sales. Sales of whiskey, bourbon, and gin, despite ending their steep decline from the previous 2 decades, were flat, and specialties (cordials, brandies, liqueurs, and mixed drinks) showed only modest increases.13 The growth within the white goods category is attributable to a small number of brands and parallels the marketing expenditures and innovations used by successful brands. Market analysts anticipate this trend continuing over the next decade.13

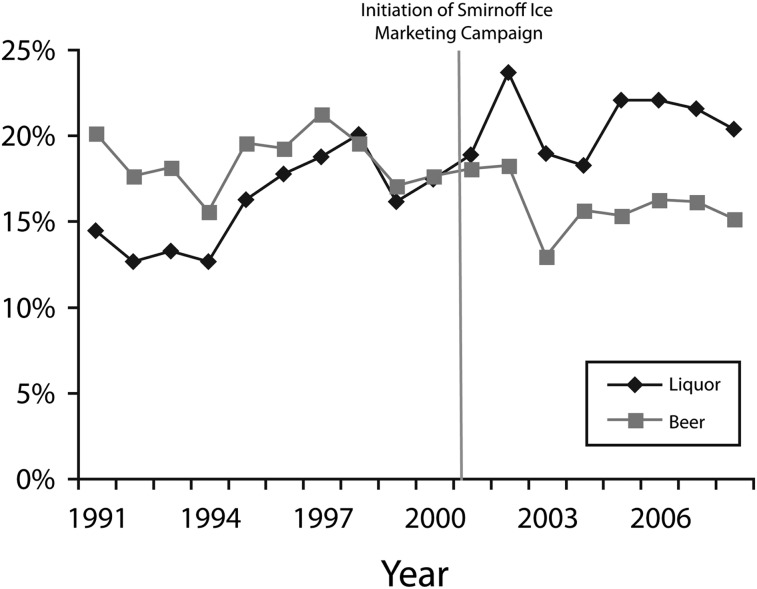

Surveys of underage drinking document a similar shift in alcoholic beverage preference among young people in the past decade that parallels the overall market shift, particularly among girls. The Monitoring the Future national survey of 8th, 10th, and 12th graders found that 12th-grade girls were significantly more likely to drink beer than distilled spirits in 2000; by 2008, their drink of choice had shifted to distilled spirits.19 The shift in preference was more pronounced among 12th-grade girls who engaged in binge drinking (Figure 3). Boys reported an increased preference for distilled spirits as well, but beer remains their most preferred beverage.

FIGURE 3—

Beverage choice among 12th-grade girls who engage in binge drinking (≥ 5 drinks per sitting): United States, 1991–2008.

Source. Johnston et al.19

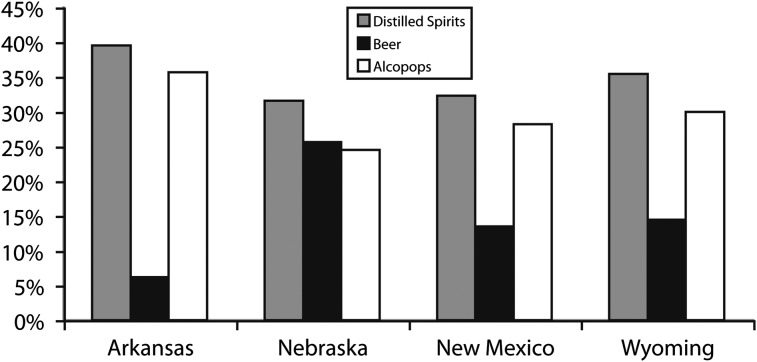

The Monitoring the Future data are limited because they do not include data for younger teens. Reports from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggest that the beverage preference shift among younger cohorts may be much more significant.36 Data from 4 states from the Youth Behavioral Risk Survey show that, among 9th- through 12th-grade girls who have consumed alcohol in the past 30 days, distilled spirits and alcopops are more popular than is beer. In 3 of the 4 states, this beverage preference is pronounced (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4—

Beverage choice among 9th- through 12th-grade girls (30 day prevalence): United States, 2005.

Source. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.36

Unfortunately, there are no brand-specific data to measure these shifting tastes among young people. As noted previously, every brand has its own marketing niche, and most brands are not designed for the youth and young adult market. Aggregate data will dilute the effects of brand-specific youth marketing tactics. With brand-specific data, the link between youth-oriented market innovations for specific brands such as Smirnoff Vodka could be documented. Without it, the connection cannot be described definitively.

Diageo's Public Relations Campaign

Diageo initiated a sophisticated public relations program during the same period that it launched the Smirnoff brand campaign. Its purpose was to convince policymakers, public health and medical groups, and the public that the company was committed to deterring underage drinking and other social harms associated with its products. Diageo hired Guy Smith, a former vice president of Philip Morris, a veteran of the tobacco wars, and a former advisor to President Clinton, to head up its marketing public relations division, which would design and implement the campaign. The following strategies were used.

1. Establish a self-regulatory structure to monitor the company's alcohol advertising. Diageo established its own responsible marketing code, which it describes as “a beacon for responsible marketing and brand innovation” according to DrinkIQ.37 The code, established in 1997, is periodically updated and states that the company's advertising must

Be aimed only at adults and never target those younger than the legal purchase age for alcohol [and] be designed and placed for an adult audience, and never be designed or constructed or placed in a way that appeals primarily to individuals younger than the legal purchase age for alcohol.38(p4)

Diageo also complies with the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States marketing code. Diageo's and the alcohol industry's self-regulatory practices generally suffer from several weaknesses, including lack of independent compliance monitors; a 30% youth audience standard, which allows for extensive youth exposure to measured media; weak controls on youth access to digital and Internet marketing; and weak standards of advertising content, that is, allowing advertising so long as it does not “primarily” appeal to underage drinkers.18,31,39

2. Broadcast “responsibility” advertisements. Between 2001 and 2005, Diageo spent 17.7% of its advertising budget on responsibility television advertising, which is focused primarily on educating viewers about how to prevent underage drinking and drunk driving—far more than any other alcoholic beverage producer.18 Even so, underage youths were far more likely to see a Diageo product advertisement than a responsibility advertisement during this period.18 The effectiveness of industry responsibility advertising has been questioned,10,18 and at least 1 study has suggested that the advertisements are designed to reinforce brand advertising messages.40

3. Fund prevention programs that focus on education, public awareness, and responsible retail practices. According to Diageo's 2009 Corporate Citizenship Report,

We support practical programmes in many of our markets to tackle particular examples of harm from alcohol misuse… . This year we led or supported over 130 such initiatives in over 40 countries. The Diageo Responsible Drinking Fund, which had resources this year of £400,000, provided financial support, backed up by expert guidance.41(p9)

Examples include DrinkIQ, a Web site providing information on alcohol and alcohol problems, programs focused on responsible alcohol retail practices, and drinking and driving and underage drinking awareness programs. As with most alcohol industry responsibility efforts, Diageo's sponsored programs are seldom evaluated and predominantly focus on providing information to consumers. The National Research Council/Institute of Medicine report concluded that such programs “have been demonstrated to be ineffective at reducing alcohol use and should be avoided.”10(p132)

4. Build partnerships with medical and public health organizations and government agencies. According to Diageo, most of its funded programs are

undertaken in partnership with other organizations including governments, non-governmental organizations, universities, researchers, physicians, [and] law enforcement.41(p10)

Medical and public health groups are a high priority for building partnerships; governmental agencies are equally important. For example, Diageo42 has reached out to the Federal Trade Commission, which regulates alcohol advertising and called for the industry to support the Federal Trade Commission's “We Don't Serve Teens Campaign.” The company's cooperation with governmental agencies on prevention efforts dovetail with Diageo's extensive political lobbying activities. Diageo and other distillers have also sponsored scientific research and sought to influence public perceptions regarding research findings.43

5. Establish industry-based “social aspects” organizations. Over the past decade, Diageo has helped organize and fund 14 social aspects organizations worldwide, including the Century Council and the International Center on Alcohol Policy in the United States.41 These industry-member organizations sponsor programs similar to those funded by the Diageo Responsible Drinking Fund and further the goals of the Diageo public relations campaign. Social aspects organizations serve the long-term marketing interests of their industry members.44

These components fit a strategy used by several industries that have products with potential public health harms: they promote ineffective self-regulatory programs, discourage governmental regulation, broadcast a message of corporate responsibility, fund programs with public relations value that do not interfere with marketing, recruit potential opponents with corporate funds, and seek opportunities to cooperate with governmental agencies that might otherwise interfere with marketing goals.

ANALYSIS

Underage drinking constitutes a public health crisis in the United States. As stated in the 2007 Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking,

The short- and long-term consequences that arise from underage alcohol consumption are astonishing in their range and magnitude… . [It] is a leading contributor to death from injuries, which are the main cause of death for people under 21 and plays a significant role in risky sexual behavior, physical and sexual assault, academic failure, and illicit drug use, among other adverse consequences.45(p10)

There is now a robust research literature documenting the effectiveness of various alcohol policies in preventing these public health harms, including raising alcohol prices through increased alcohol taxes and reducing alcohol availability.10,43 Counteradvertising (public service advertisements designed to discredit product advertising messages) and other controls of alcohol advertising and promotions are also promising policy interventions.10,43 Applying these strategies to alcopops, which have a particular appeal for youths, is an important aspect of reducing problems associated with underage drinking.

As the Smirnoff case study documents, the alcohol industry is involved in an intense competition for the youth market. The industry's ability to engage in this competition is dependent on engaging in and expanding the very practices that these alcohol policies would restrict. This fact suggests the importance of Diageo's public relations and lobbying activities. The industry's success is particularly noteworthy, given the fact that surveys repeatedly show that the public supports these and other alcohol policy interventions.46

The practices documented here are not unique to Diageo or the alcohol industry. They are commonly used by corporations to sell a wide variety of consumer products that have potentially adverse effects on public health, including tobacco, prescription drugs, automobiles, firearms, and unhealthy foods.47–51 The dynamics are remarkably similar in terms of corporate marketing strategies, use of public relations, and reliance on political lobbying.

Case studies of corporate practices that use qualitative research methods but do not include control groups or baseline measures cannot support causal inferences regarding public health effects.52 In particular, this case study does not provide a basis for concluding that overall youth consumption increased as a result of Diageo's Smirnoff campaign. Nevertheless, case studies can provide insights into the dynamics of the interaction between those practices and public health outcomes and can serve as a foundation for identifying priorities for research studies using more sophisticated methodologies and for designing and implementing advocacy campaigns.53 Case studies of tobacco industry marketing practices, such as those examining R.J. Reynolds's Joe Camel marketing campaign, illustrate this point: they served as a foundation for significant public health gains in tobacco control.47

Experiences in related fields can serve to guide alcohol policy research and advocacy. Unfortunately, the alcohol industry's practices are understudied relative to many other corporate sectors. The Smirnoff case study, therefore, addresses an important gap in the research literature. It points to several important research questions, such as

How do alcohol industry practices compare with the actions of other corporate players?

What lessons can be learned from tobacco control efforts?

Has the increased popularity of specific distilled spirits brands influenced youth consumption and related problems and, if so, how?

Are Diageo's lobbying and public relations activities integral to its marketing plans, and what effect do they have on alcohol policy development and public health advocacy?

Research studies addressing other consumer products provide some guidance on these issues. For example, tobacco control studies have found that corporate marketing contributes to youth and young adult tobacco use; research also indicates that tobacco company public relations and marketing campaigns are directly linked.47,49,54

Because alcohol industry practices have not been a priority for public health, basic surveillance data (e.g., brand preferences among youths and information regarding digital marketing activities) are not collected, and public health agencies at local, state, and federal levels are largely silent on the topic. Collecting and analyzing these data, conducting research studies that focus on corporate practices, and promoting the implementation of effective alcohol policies should be high priorities for the public health field.

Acknowledgments

Partial funding for the article was provided by the Institute on Medicine as a Profession (IMAP).

An earlier version of this article was delivered at the Industry-Medicine Conference sponsored by IMAP, Columbia University, November 2, 2009.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was needed because no human research participants were involved.

References

- 1.Moore M, Gerstein D, Alcohol and Public Policy: Beyond the Shadow of Prohibition. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1981 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Impact Databank Impact Databank Review and Forecast: The U.S. Spirits Market. New York: M. Shanken Communications; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine HG. The birth of American alcohol control: Prohibition, the power elite, and the problem of lawlessness. Contemp Drug Probl. 1985;12:63–115 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stack M, Gartland M. The repeal of Prohibition and the resurgence of the national breweries: productive efficiency or path creation? J Manage Hist. 2005;43(3):420–432 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pennock P. The evolution of U.S. temperance movements since repeal: a comparison of two campaigns to control alcohol marketing, 1950s and 1980s. Soc Hist Alcohol Drugs. 2005;20(1):14–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosher JF, Cowan C. Public health implications of beverage marketing: alcohol as an ordinary consumer product. Contemp Drug Probl. 1985;12(4):621–657 [Google Scholar]

- 7.McBride R. Industry structure, marketing, and public health: a case study of the U.S. beer industry. Contemp Drug Probl. 1985;12:593–612 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kusserow R. Youth and Alcohol: A National Survey. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General; 1991. Publication OEI-09-91-00652 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Volume I: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies; 2010. NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS publication no. SMA 10-4856 [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Research Council & Institute of Medicine Reducing Underage Drinking: A Collective Responsibility. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mintel Oxygen Group Distilled spirits: white spirits—US; February 2005. Available at: http://oxygen.mintel.com/sinatra/oxygen/display/id=150060/display/id=150060/display/id=150060. Accessed June 13, 2011

- 12.Mosher JF, Johnsson D. Flavored alcoholic beverages: an international marketing campaign that targets youth. J Public Health Policy. 2005;26(3):326–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Impact Databank Impact Databank Review and Forecast: The U.S. Spirits Market. New York: M. Shanken Communications; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth Youth Exposure to Alcohol Ads on Television, 2002. Washington, DC: Georgetown University; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth Still Growing After All These Years: Youth Exposure to Alcohol Advertising on Television, 2001–2005. Washington, DC: Georgetown University; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth Youth Exposure to Alcohol Advertising on Television, 2001–2007. Washington, DC: Georgetown University; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Impact Databank Impact Databank Review and Forecast: The U.S. Spirits Market. New York: M. Shanken Communications; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth Drowned Out: Alcohol Industry “Responsibility” Advertising on Television 2001–2005. Washington, DC: Georgetown University; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnston L, O'Malley P, Bachman J, Schulenberg J. Monitoring the Future National Results on Adolescent Drug Use, 1975–2009. Volume 1: Secondary School Students. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2010. NIH publication 09-7402 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnston L, O'Malley P, Bachman J, Schulenberg J. Monitoring the Future National Results on Adolescent Drug Use, 1975–2009. Volume 2: College Students and Adults Ages 19–50. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2010. NIH publication 09-7403 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolfson M, Martin B, Wagoner K, Song E. FMB use in a multi-state sample of adolescents. Paper presented at: 133rd Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association; December 2005; Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dauphinee A, Henderson V, Henrikson L. Alcopop Consumption and Ad Recognition Among Ethnic/Racial Minority Middle School Students. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford University School of Medicine; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flavored Malt Beverage Coalition Fact Sheet. Greens Farms, CT; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Department of the Treasury, Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau Flavored malt beverages and related proposals. Fed Regist. 2003;68:14 292–14 303 [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Department of the Treasury, Alcohol and Tobacco Trade and Tax Bureau Flavored malt beverages and related regulatory amendments. Fed Regist. 2005;70:194–237 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mosher JF. Litigation and alcohol policy: lessons from the US tobacco wars. Addiction. 2009;104(suppl 1):27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.US Department of the Treasury, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms ATF Ruling 96–1; March 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mosher J. Special Report: Status of State Campaigns to Restrict the Availability of Alcopops. Felton, CA: Alcohol Policy Consultations; 2009. Available at: http://www.alcoholpolicyconsultations.com/downloads/Alcopop_status_report_2-09-09.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stoddard M. Malt drink tax ruling appealed. World Herald; February 23, 2011. Available at: http://omaha.com/article/20110223/NEWS97/702239887/0. Accessed March 23, 2011

- 30.Elliot S. Liquor industry ends its ad ban in broadcasting. New York Times. November 8, 1996:A1 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chester J, Montgomery K, Dorfman L. Alcohol Marketing in the Digital Age. Washington, DC: Center for Digital Democracy; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bloomberg News Service Diageo woos iPhone users, women to beef up price. Bloomberg News Service; March 1, 2010. Available at: http://www.punchng.com/Articl.aspx?theartic=Art201003010184140. Accessed May 11, 2010

- 33.Goodman J. Popular new drinking game raises question, who's “icing” whom? New York Times; June 6, 2010. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/09/business/media/09adco.html?_r=1. Accessed June 11, 2011

- 34.Impact Ready-to-drinks category expands. Impact Magazine. May 15, 2003:4 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brownsell A. Smirnoff named most valuable drinks brand. Marketing Magazine; May 10, 2010. Available at: http://marketingmagazine.co.uk/news/1001904/Smirnoff-named-valuable-drinks-brand. Accessed May 11, 2010

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Types of alcoholic beverages usually consumed by students in 9th–12th grades—four states. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(29):737–740 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drink IQ. Diageo and Responsible Drinking. Available at: http://www.drinkiq.com/en-US/pages/diageo-history-of-responsibility.aspx. Accessed March 23, 2011

- 38.Diageo Marketing Code: Promoting Responsible Drinking. Available at: http://www.dmcapproval.com/codes/Diageo-Marketing-Code%20DMC.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2011

- 39.Xuan Z, Babor T. Perceptions of alcohol advertising content by vulnerable populations: is industry self-regulation sufficient? Paper presented at: 135th Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association; November 6, 2007; Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dejong W, Atkins CK, Wallack L. A critical analysis of “moderation” advertising sponsored by the beer industry: are responsibility drinking commercials done responsibly? Milbank Q. 1992;70(4):661–678 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diageo Corporate citizenship report. London: Diageo; 2009. Available at: http://www.diageo.com/Lists/Resources/Attachments/218/Diageo_CR09.pdf. Accessed June 21, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diageo. Diageo calls on alcohol industry to support “We Don't Serve Teens Campaign”. [press release]; March 1, 2007. Available at: http://hispanicprwire.com/News/in/8150/7/diageo-invita-a-la-industria-del. Accessed March 23, 2011.

- 43.Babor T, Caetano R, Casswell Set al. Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity. 2nd ed New York: Oxford University Press; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jernigan D. Confusion, Contention and Collaboration: Alcohol Producers and Global Public Health. Baltimore, MD: Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 45.US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking. Washington, DC; 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wagenaar AC, Harwood EM, Toomey TL, Denk CE, Zander KM. Public opinion on alcohol policies in the United States: results from a national survey. J Public Health Policy. 2000;21(3):303–327 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cohen JB. Playing to win: marketing and public policy at odds over Joe Camel. JPP&M. 2000;19(2):155–167 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Freudenberg N, Galea S. The impact of corporate practices on health: implications for health policy. J Public Health Policy. 2008;29(1):86–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glantz S, Slade J, Bero L, Hanauer P, Barnes D. The Cigarette Papers. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harris JL, Pomeranz JL, Lobstein T, Brownell KD. A crisis in the marketplace: how food marketing contributes to childhood obesity and what can be done. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:211–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nestle M. Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hornik R. Evaluation design for public health communication programs. : Hornik R, Public Health Communication: Evidence for Behavior Change. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002:385–405 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Freudenberg N, Bradley SP, Serrano M. Public health campaigns to change industry practices that damage health: an analysis of 12 case studies. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36(2):230–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Biener L, Siegel M. Tobacco marketing and adolescent smoking: more support for a causal inference. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(3):407–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]