Abstract

We used a quasi-experimental design to examine the impact of intensive case management (ICM) on preventing 3-year subsequent births for low-income adolescent mothers. We used χ2 and mediation analyses, respectively, to test whether ICM reduced likelihood of subsequent births and whether birth control and perceived social support mediated this relationship. Participants in ICM were less likely to have a subsequent birth within 3 years, but we found no evidence for mediators. This study suggests that ICM may be effective in preventing subsequent births for adolescents.

The United States has the highest adolescent pregnancy rate of any industrialized country with 7% of female adolescents aged 15 to 19 years becoming pregnant annually.1,2 Adolescent parenting puts both mother and child at risk for poor health and socioeconomic outcomes, resulting in significant costs to our nation.3

An estimated 20% to 37% of adolescent mothers have a subsequent birth within 2 years of their first child.4–6 Such adolescents are at great risk for premature birth,7 long-term poverty, school difficulties, drug use, and delinquency.8,9 Ethnic minority status, lower educational attainment,10 involvement or living with a partner, and birth control5,11–16 appear to be associated with subsequent births for adolescent mothers.

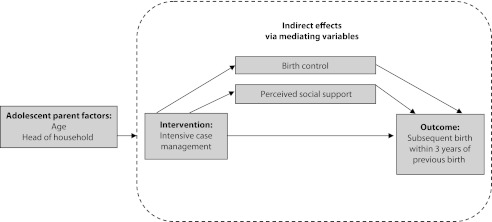

Social support programs, including mentoring, nurse home visitation, and school-based models,17,18 demonstrate positive outcomes19–21; however, the mechanisms that prevent subsequent births are not well understood.16 A relationship-focused, intensive case management (ICM) program employed case managers with college degrees to deliver a resiliency-based developmental assets22–24 approach to serving low-income parenting adolescents. The long-term, supportive relationship between client and case manager (minimum bimonthly contacts for up to 3 years) was expected to foster social support and birth control that would mediate a reduction in subsequent births (Figure 1).5

FIGURE 1—

Conceptual model for intensive case management client outcome.

METHODS

We used a quasi-experimental design to make comparisons between ICM for at least 6 months (mean = 2.25 years; SD = 0.97 years) and no ICM. We tracked subsequent births within 3 years. We assessed social support biannually; we assessed birth control and head of household quarterly. For feasibility, case managers administered measures to ICM participants. Protocol was approved by university Office of Research Support.

Sample

We recruited the ICM clients onsite (25% declined); for the comparison group, we used fliers to recruit recipients of Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children who were attending adolescent health clinics. Overall, 85% were Hispanic, 60% were in their second or third trimester, and the remainder were parents of children younger than 18 months.

Overall, 144 female participants (86 ICM; 58 comparison) consented and completed baseline assessments. We used data from 87 participants (55 ICM; 32 comparison) in the analysis because birth status information was available through case and medical records. The comparison group was older and more often head of household with partner. No significant baseline differences occurred between participants and those who dropped out.

Measures and Analyses

The dependent variable was subsequent birth within 3 years. The independent variable was ICM. Control variables included age and head of household. Mediating variables included birth control (yes or no; and then open-ended, forced choice of primary method used quarterly, including abstinence) and social support (Family Support Scale, 0.77 estimated reliability for 18 items that measure helpfulness to mothers).25

Because of the small sample, we used a 10% significance level. We conducted χ2 analysis to assess differences in subsequent birth rate between groups. We conducted path analysis with MPlus version 5.1 (Muthén and Muthén, Los Angeles, CA) to assess whether social support and birth control mediated the relationship between ICM and subsequent birth rate. We examined mediation through a series of regression equations.26 First, we examined the total effects of the model. Next, we examined the relationship between the intervention and the mediators to assess indirect effects. Finally, we examined the relationship between mediators and subsequent births.

RESULTS

About 16% of the ICM group experienced a subsequent birth within 3 years compared with 31% of comparison group (χ21 = 2.63; P < .09; Table 1).

TABLE 1—

Results From Primary Analyses of Intensive Case Management Versus Comparison Group on 3-Year Subsequent Births Among Adolescent Mothers

| Descriptive Analysis |

Meditational Analysis of Subsequent Births (n = 87) |

|||||

| Intervention (n = 55), % or Mean (SD) | Comparison (n = 32), % or Mean (SD) | Coefficient (SE) | z Statistic | 2-Tailed P | Bootstrap 95% CI | |

| Model results | ||||||

| Intervention* | 16 | 31 | −0.05 (0.53) | −0.09 | .93 | … |

| Age,*** y | 15.4 (1.6) | 17.7 (1.0) | 0.12 (0.15) | 0.754 | .45 | … |

| Head of household | ||||||

| With partner** | 9 | 28 | ||||

| Self | 13 | 19 | −0.07 (1.04) | −0.066 | .95 | … |

| An adult | 78 | 53 | 0.17 (0.49) | 0.334 | .74 | … |

| Birth control | 87 | 78 | −0.38 (0.22) | −1.780 | .08 | … |

| Social supporta,* | 27.2 (12.2) | 23.2 (6.8) | −0.03 (0.02) | −1.329 | .18 | … |

| Indirect effects of intervention on mediators | ||||||

| Birth control | 0.70 (0.60) | 1.157 | .25 | -0.29, 1.69 | ||

| Social support | 3.36 (2.19) | 1.533 | .13 | -0.25, 6.96 | ||

| Indirect effects of mediators on subsequent births | ||||||

| Birth control | −0.27 (0.33) | −0.814 | .42 | -0.81, 0.27 | ||

| Social support | −0.08 (0.10) | −0.856 | .39 | -0.24, 0.08 | ||

Note. CI = confidence interval.

The sum of the participants' ratings for 18 items representing helpfulness from available supports, such as parents, each scored from 0 to 4 (0 = not at all helpful to 4 = extremely helpful).

*P ≤ .1; **P ≤ .01; ***P ≤ .001; significant differences between intervention and comparison groups. The small sample size, we considered significance at P ≤ .1.

The overall model was not significant. In addition, ICM had no significant indirect effects on mediating variables, and proposed mediating variables had no significant indirect effects on the outcome.

The only significant finding was in the full model for the relationship between birth control and subsequent births. In a posthoc analysis, adolescents with a subsequent birth were less likely to report using birth control (χ21 = 4.14; P < .05). At last report, primary birth control method included abstinence, condoms, Depo-Provera, intrauterine device, NuvaRing, patch, and pill.

DISCUSSION

Although this study provided some evidence that ICM reduces subsequent births, there was no evidence for the proposed mediation. Adolescents who reported using birth control were less likely to experience subsequent births, although 18% of adolescents who reported using birth control had subsequent births.

It is curious that social support did not appear to mediate the relationship between ICM and subsequent births. Although it is likely that small sample size and measurement (especially for younger clients) played a role, other intervention factors may be more salient. Research shows that mothers often report knowledge of contraception and how to access it, but that their pregnancies are more intentional than previously understood.27 Extensive qualitative research with young, urban mothers has demonstrated that they choose motherhood as an entry into adulthood, formulating career and relationships around their role as mother.27

Limitations of this study include small sample size, nonrandom assignment, between-group differences, higher attrition rate for the comparison, and potential social desirability. A more precise measure of birth control that includes consistency is desirable. Selection bias and group differences may help account for the difference in subsequent birth rates.

Although results suggest that ICM may help prevent subsequent births for low-income parenting adolescents, actual prevention mechanisms need further exploration.

Acknowledgments

This article and research was supported by the Office of Adolescent Pregnancy Programs, Office of Population Affairs, US Department of Health and Human Services (grant APH200602270).

The authors thank program directors Robin Rosell, Peg Gavin, Monica Perez, Amy Pierce, Jill Smith, and Karen Hopkins; the case managers; and the participants for their contributions to this research. We also extend appreciation to LifeWorks, People's Community Clinic, Any Baby Can, Austin Child Guidance Center, and St David's Foundation for their collaboration and support of this project and to RTI International for its input and review. We also acknowledge guidance from Nate Marti on the statistical analyses.

Note. The interpretations and conclusions presented in this article do not necessarily represent the position of the Office of Adolescent Pregnancy Programs or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Human Participant Protection

The institutional review board of The University of Texas at Austin approved the protocol for this study, 2005-11-0097.

References

- 1.Kost K, Henshaw S. US Teenage Pregnancies, Births and Abortions, 2008: National Trends by Age, Race and Ethnicity. New York, NY: Guttmacher Institute; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demographic Yearbook 2006. Vol. 58 New York, NY: United Nations Publications; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffman SD. Kids Having Kids: Economic Costs & Social Consequences of Teen Pregnancy. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meade CS, Ickovics JR. Systematic review of sexual risk among pregnant and mothering teens in the USA: pregnancy as an opportunity for integrated prevention of STD and repeat pregnancy, Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(4):661–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klerman L. Another Chance: Preventing Additional Births to Teen Mothers. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rigsby DC, Macones GA, Driscoll DA. Risk factors for rapid repeat pregnancy among adolescent mothers: a review of the literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 1998;11(3):115–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith GC, Pell JP. Teenage pregnancy and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes associated with first and second births: population based retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2001;323(7311):476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furstenberg FF, Brooks-Gunn J, Morgan SP. Adolescent Mothers in Later Life. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polit DF, Kahn JR. Early subsequent pregnancy among economically disadvantaged teenage mothers. Am J Public Health. 1986;76(2):167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore KA, Ryan S, Manlove J, Mincieli L, Schelar E. High-risk subsequent births among co-residential couples: the role of fathers, mothers, and couples. Fathering. 2009;7(1):91–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Black MM, Bentley ME, Papas MAet al. Delaying second births among adolescent mothers: a randomized, controlled trial of a home-based mentoring program. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):e1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boardman LA, Allsworth J, Phipps MG, Lapane KL. Risk factors for unintended versus intended rapid repeat pregnancies among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(4):597.e1–e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillmore MR, Lewis SM, Lohr MJ, Spencer MS, White RD. Repeat pregnancies among adolescent mothers. J Marriage Fam. 1997;59(3):536–550 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalmuss DS, Namerow PB. Subsequent childbearing among teenage mothers: the determinants of a closely spaced second birth. Fam Plann Perspect. 1994;26(4):149–153, 159 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens-Simon C, Kelly L, Kulick R. A village would be nice but… : it takes a long-acting contraceptive to prevent repeat adolescent pregnancies. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21(1):60–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raneri LG, Wiemann CM. Social ecological predictors of repeat adolescent pregnancy. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2007;39(1):39–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Key JD, Barbosa GA, Owens VJ. The Second Chance Club: repeat adolescent pregnancy prevention with a school-based intervention. J Adolesc Health. 2001;28(3):167–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Solomon R, Liefeld CP. Effectiveness of a family support center approach to adolescent mothers: repeat pregnancy and school drop-out rates. Fam Relat. 1998;47(2):139–144 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Prevention Council National Prevention Strategy. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Omar HA, Fowler A, McClanahan KK. Significant reduction of repeat teen pregnancy in a comprehensive young parent program. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2008;21(5):283–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rabin JM, Seltzer V, Pollack S. The long term benefits of a comprehensive teenage pregnancy program. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1991;30(5):305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scales PC, Benson PL, Leffert N, Blyth DA. Contribution of developmental assets to the prediction of thriving among adolescents. Appl Dev Sci. 2000;4(1):27–46 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scales PC, Leffert N. Developmental Assets: A Synthesis of the Scientific Research on Adolescent Development. Minneapolis, MN: Search Institute; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scarborough MK, Lewis CM, Kulkarni S. Enhancing adolescent brain development through goal-setting activities. Soc Work. 2010;55(3):276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cherniss C, Herzog E. Impact of home-based family therapy on maternal and child outcomes in disadvantaged adolescent mothers. Fam Relat. 1996;45(1):72–79 [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edin K, Kefalas M. Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood Before Marriage. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press; 2007 [Google Scholar]