Abstract

The interaction of macrophages with infectious agents leads to the activation of several signaling cascades, including mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases, such as p38. We now demonstrate that p38 MAP kinase–mediated responses are critical components to the immune response to Borrelia burgdorferi. The pharmacological and genetic inhibition of p38 MAP kinase activity during infection with the spirochete results in increased carditis. In transgenic mice that express a dominant negative form of p38 MAP kinase specifically in macrophages, production of the invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cell–attracting chemokine MCP-1 and of the antigen-presenting molecule CD1d are significantly reduced. The expression of the transgene therefore results in the deficient infiltration of iNKT cells, their decreased activation, and a diminished production of interferon γ (IFN-γ), leading to increased bacterial burdens and inflammation. These results show that p38 MAP kinase provides critical checkpoints for the protective immune response to the spirochete during infection of the heart.

Macrophages play a critical role in the defense against infectious microorganisms. These phagocytic cells detect pathogens via pattern recognition receptors, such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), scavenger receptors, and integrins [1–3]. This interaction results in the initiation of an array of signaling pathways, leading to the activation of the transcription factor NF-κB, as well as mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases, such as p38 [4, 5]. The end result is the production of proinflammatory factors, internalization and degradation of the infecting agent, and the increased ability to present antigen to CD4+ T and invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells [6–8].

Signal transduction via MAP kinases is important in a variety of cellular responses. Several MAP kinase signal transduction pathways have been defined in mammalian cells [9, 10] that are activated by phosphorylation on Thr and Tyr residues by dual-specificity MAP kinases [11]. In mammalian cells, p38 MAP kinase is activated by MKK3 and MKK6 [12–15] and can be triggered by multiple stimuli, such as proinflammatory cytokines (eg, interleukin 1β and tumor necrosis factor), Toll-like receptor (TLR) stimulation, and physical-chemical changes in the extracellular milieu caused by environmental stress [11, 16–18]. The kinase is a selective target for pyridinyl imidazole [19] and other synthetic molecules [20]. Several clinical trials have tested the use of these drugs for the treatment of, among others, inflammatory neural disorders and rheumatoid arthritis [21–23]. The potential clinical use of p38 MAP kinase inhibitors is based on their ability to inhibit proinflammatory responses. However, the kinase also regulates other cellular processes [24], including those important for controlling infection.

B. burgdorferi is the causative agent of Lyme disease, a prevalent vector-transmitted infection that is endemic in areas of the United States. Among the symptoms occurring as a result of infection with B. burgdorferi, Lyme arthritis and carditis may present to varying degrees in patients infected with the spirochete. The cellular infiltrate in the inflamed joints and hearts of patients and mice experimentally infected with the spirochete are distinct: neutrophils are predominant in arthritis, while carditis is characterized by a macrophage infiltrate at the base of the heart, surrounding the aortic valve [25, 26]. Spirochete colonization of the heart results in early infiltration of macrophages and proinflammatory cytokine production in response to spirochetal antigens [25, 27, 28]. p38 MAP kinase activity controls the proinflammatory response to B. burgdorferi in phagocytic cells by regulating the activation of NF-κB in a MSK1-dependent fashion [17]. p38 MAP kinase also regulates the effector cell function, but not the differentiation, of spirochete-specific CD4+ T cells [29]. The analysis of mice that are deficient for the upstream p38 MAP kinase activator, MKK3, showed decreased arthritis incidence [5]. The role of MKK3 in carditis severity, however, was not addressed. Importantly, the specific role of p38 MAP kinase in the control of inflammation severity during infection with B. burgdorferi has not been assessed.

Here we show that the inhibition of p38 MAP kinase increases B. burgdorferi–induced carditis. Moreover, specific inhibition of p38 MAP kinase in macrophages increases the number of heart spirochetes and perturbs iNKT cell recruitment and activation through its ability to regulate the expression of the chemokine MCP-1 and the antigen-presenting molecule CD1d, respectively. Thus, activation of p38 MAP kinase in macrophages is an essential component in the clearance of B. burgdorferi from the host.

METHODS

Generation of cd11b-dnp38 Transgenic Mice

The cd11b-dnp38 MAP kinase transgene was constructed using the cd11b promoter extending from base pairs −1704 to +83 and included 83 base pairs of the 5′ untranslated region, extending up to the ATG codon (kindly provided by Dr Daniel G. Tenen [30]). The plasmid also contains a 2.1-kb fragment of the polyadenylation signals and intron sequences of the human growth hormone [31] (Figure 2A). The dnp38 gene was inserted between both sequences by digestion with HindIII and XbaI. The transgene was digested with HindIII and NotI and purified by electroelution prior to microinjection into fertilized eggs. The microinjected fertilized eggs were then implanted into pseudopregnant females. Founders were identified by slot blot, using a BamHI-SacI 0.5-kb fragment from the human growth hormone gene (hGH), and by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), using the primers (5′-AGG ATC CCA AGG CCC AAC TCC-3′ and 5′-CTC CTT AGT CTC CTC CTC TTA T-3′). The transgenic (Tg) mice have been backcrossed into the C3H/HeN background for at least 10 generations to establish stable Tg mouse lines. The experiments described herein have been obtained using 2 lines of Tg mice (171 and 178). The expression of the transgene in different tissues and bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMMs) was determined by reverse-transcription PCR (RT-PCR), using the primers 5′-GCC CTT GCA CAT GCC TAC TTT GC-3′ and 5′-GAG GGA GGT CTG GGG GTT CTG-3′.

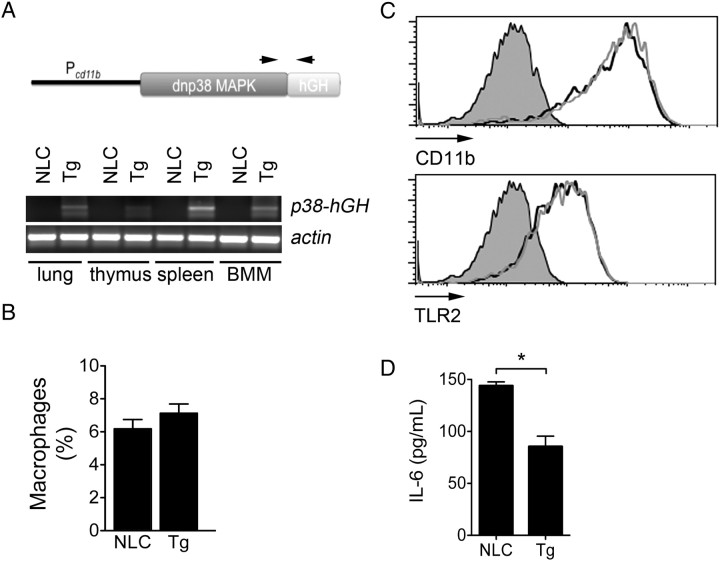

Figure 2.

Generation of cd11b-dnp38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase transgenic (Tg) mice. A, Schematic representation of the dnp38 MAP kinase gene used to generate the Tg mice (top), showing the promoter (cd11b), the dnp38 gene, and the human growth hormone polyA/intron signal sequence. The arrows represent the localization of the primers used to detect messenger RNA expression in different tissues (bottom) plus bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMMs). Primers for actin were used as control. B, Percentage of F4/80+ cells in the spleens of Tg and negative littermate control (NLC) mice. Mice aged 6–8 weeks were analyzed for macrophage concentration by flow cytometry upon staining with an anti-F4/80 monoclonal antibody. The analysis was performed on gated live cells according to their forward scatter versus side scatter profile. C, Surface expression levels of CD11b (top) and TLR2 (bottom) in BMMs from Tg mice (grey histograms) and NCL mice (black histograms), determined by flow cytometry. D, Tg and NLC BMMs were stimulated with Borrelia burgdorferi (multiplicity of infection = 25) for 16 hours. The stimulation supernatants were then assessed for interleukin 6 (IL-6) by enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay. *P < .01, by the Student t test.

Infection With B. burgdorferi and Evaluation of Joint and Cardiac Inflammation

Groups of 5–6 mice were infected by subcutaneous injection with 105 B. burgdorferi in the midline of the back, as previously described [29]. At sacrifice, the mice were analyzed for inflammation by histological evaluations of arthritis and carditis. Joints and hearts (cut in half across the atria and ventricles) were fixed in 10% formalin and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The joints were also decalcified. Signs of arthritis were evaluated as described previously [32] on the basis of assessment of histological parameters, such as exudation of fibrin and inflammatory cells into the joints, alteration in the thickness of tendons or ligament sheaths, and hypertrophy of the synovium [33–35]. Signs of carditis were evaluated on the basis of the cardiac inflammatory infiltrate [33, 36]. Inflammation was blindly scored on a scale of 0 (no inflammation), 1 (mild inflammation), 2 (moderate inflammation), or 3 (severe inflammation). The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Massachusetts–Amherst approved all procedures involving animals.

Determination of Bacterial Burdens

The number of spirochetes in skin (ear) and heart tissue was determined by real-time PCR, using primers specific for the recA gene (5′-GTG GAT CTA TTG TAT TAG ATG AGG CTC TCG-3′ and 5′-GCC AAA GTT CTG CAA CAT TAA CAC CTA AAG-3′) [37] and the fluorescent DNA dye SYBR Green (Roche, Nutley, NJ). Total DNA was extracted using the Qiagen tissue kit in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). PCR conditions were as follows: forty 30-second cycles of denaturing (at 95°C) and annealing/extension (at 60°C). Use of these conditions permits detection of approximately 10 spirochetes per picogram of total DNA [38]. The number of spirochetes in each sample were standardized to micrograms of total DNA with the use of primers corresponding to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (5′-CCA TCA CCA TCT TCC AGG AGC GAG-3′ and 5′-CAC AGT CTT CTG GGT GGC AGT GAT-3′) by real-time PCR [38].

Inhibition of p38 MAP Kinase During Infection With B. burgdorferi

The pharmacological inhibitor SB203580 (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) was resuspended in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), followed by dilution in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). C3H/HeN mice were administered SB203580 (1 mg/kg) or vehicle (PBS, DMSO) by intraperitoneal injection, in a 200 μL volume, every other day beginning the day of infection with B. burgdorferi [29]. Mice were sacrificed at 2 weeks of infection.

Determination of Expression Levels of cd1d, inkt, mcp-1, and ifnγ in Cardiac Tissue

RNA was extracted from half of the heart by the isothiocyanate method, following the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The RNA was treated with DNase I (Promega, Madison, WI), and reverse transcribed using oligo dT primers (Promega) and Moloney-murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega) to generate complementary DNA. Real-time PCR was then performed using the primers for cd1d (5′-GAC ACC TGC CCC CTA TTT GT-3′ and 5′-TGG CTT CTC TTG CTT CTC TAG GTC-3′), vα14i-jα18 (NKT cells; 5′-CAC CCT GCT GGA TGA CAC TGC C-3′ and CTC CAA AAT GCA GCC TCC CTA AG-3′), ifnγ (5′-GCG TCA TTG AAT CAC ACC-3′ and 5′-GGA CCT GTG GGT TGT TGA CC-3′), mcp-1 (5′-CGG AAC CAA ATG AGA TCA GAA CC-3′ and 5′-GCT GCA GAT TTA CGG GTC AAC TTC-3′), and actin (5′-GAC GAT GCT CCC CGG GCT GTA TTC-3′ and 5′-TCT CTT GCT CTG GGC CTC GTC ACC-3′) in an Mx3005P QPCR System (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Fold-induction of the genes were calculated relative to actin values, using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Generation of BMMs

Murine BMMs were generated as described elsewhere [33]. Cells were collected from the femoral shafts by flushing with 1 mL of cold Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and antibiotics. The cell suspensions were dispersed of cell clumps, treated with ACK lysis buffer, and cultured with 20% L929 supplemented RPMI in 100 mm × 15 mm Petri dishes (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) for 8 days. Following incubation, nonadherent cells were eliminated, and adherent macrophages were scraped, counted, and prepared for analysis.

Phagocytosis Assay

GFP-expressing B. burgdorferi, strain 297 (Bb914 [39]), were incubated with BMMs in antibiotic-free medium at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10. To distinguish between binding and internalization of spirochetes, the cells were incubated at 4°C and 37°C in parallel. The incubation at 4°C results in the binding but not internalization of spirochetes [40]. After the incubation, the cells were extensively washed to eliminate surface-bound spirochetes and were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Cytokine and B. burgdorferi–specific Immunoglobulin G (IgG) Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbant Assay (ELISA)

The levels of IFN-γ produced ex vivo by splenocytes following injection of cd11b-dnp38 mice and negative littermate controls (NLCs) with α-galactosylceramide (αGalCer) were determined by capture ELISA, according to manufacturer's recommendations, using the BD optEIA IFN-γ kit II (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). MCP-1 and interleukin 6 (IL-6) levels produced by BMMs were determined using the BD optEIA MCP-1 and IL-6 kits, respectively (BD Biosciences).

The analysis of B. burgdorferi–specific sera IgG levels was determined by coating 96-well plates with 0.5 μg/mL of a B. burgdorferi lysate incubated with serial 2-fold dilutions starting at 1/100, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (BD Biosciences) (1/10 000 dilution). The reactions were developed using 1-component tetramethylbenzidine substrate and were stopped with tetramethylbenzidine stop solution (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD).

Flow Cytometry

A total of 106 splenocytes were incubated for 5 minutes with Fc block (BD Biosciences) and for 45 minutes at 4°C with F4/80APC (BM8, eBioscience, San Diego, CA). The cells were washed and resuspended in PBS plus 1% FCS for analysis by flow cytometry, using an LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The data were analyzed with FlowJo for Mac, version 8.6 (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

To evaluate the surface expression in BMMs, 106 cells were incubated for 5 minutes with Fc block and for 45 minutes at 4°C with TLR2PE (6C2, eBioscience), CD11bPE (M1/70, BD Biosciences), or CD1dPE (1B1, BD Biosciences). The macrophages were washed and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Cytokine Induction by αGalCer

A suspension of αGalCer (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY) was prepared in DMSO, followed by dilution in PBS plus 0.5% Tween-20. αGalCer (100 ng/g) or vehicle (PBS plus 0.5% Tween-20) was administered by intraperitoneal injection in a 100 μL volume. NLC and cd11b-dnp38 mouse splenocytes were harvested after 12 hours and cultured in Click's media (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% FCS (Hyclone Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Lonza, Allendale, NJ), L-glutamine (Sigma), and 4.4 μL/L of 2-metcaptoethanol (Sigma) for 72 hours. Supernatants were collected and analyzed by ELISA for cytokine production.

Statistical Analysis

The results are presented as means ± standard error. Significant differences between means were calculated with the Student t test. P values of ≤.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

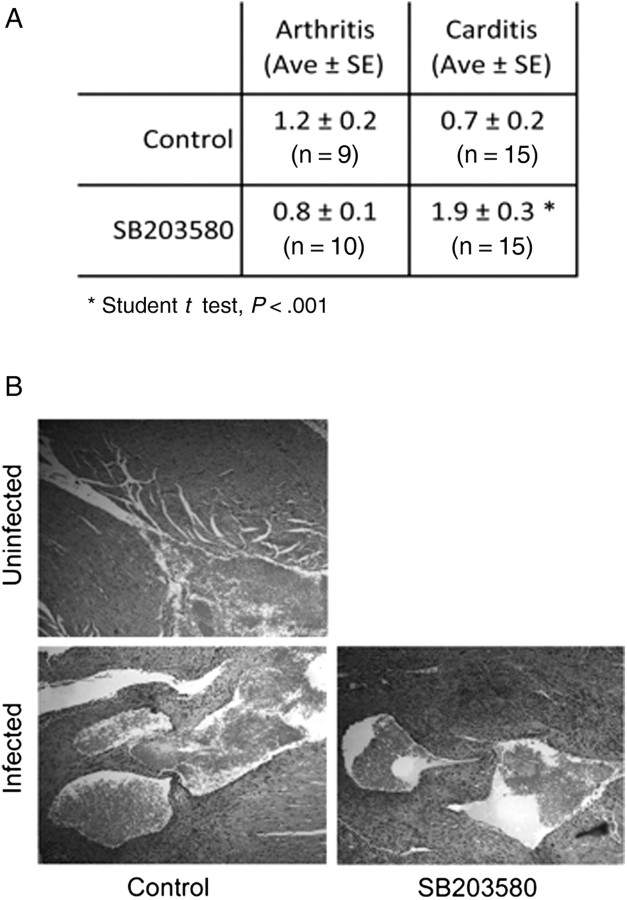

Inhibition of p38 MAP Kinase During Infection With B. burgdorferi Results in Increased Carditis

p38 MAP kinase is an important regulator of innate and adaptive immune responses [24]. To assess the specific role of p38 MAP kinase activity in the development of acute inflammation during infection with B. burgdorferi, we first investigated pathology in mice that had been treated with the specific pharmacological inhibitor of p38 MAP kinase, SB203580, during infection. Although the arthritis severity in the SB203580-treated mice was reduced compared with that in control-treated mice, the difference was not significant (P > .05, by the Student t test; Figure 1A). However, SB203580 treatment resulted in a significant increase in the severity of cardiac inflammation, compared with vehicle control–treated, B. burgdorferi–infected mice (Figure 1A and 1B).

Figure 1.

Inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase during infection with Borrelia burgdorferi results in increased Lyme carditis. A, Arthritis and carditis in C3H mice infected with B. burgdorferi and treated with the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580 every other day during infection or in control injected mice (Control). The mice were infected with 105 spirochetes and treated with 1 mg/kg of SB203580. The mice were analyzed after 2 weeks of infection. Ave, average; SE, standard error. B, Representative hematoxylin and eosin histological sections of the hearts of the infected mice. Carditis was scored on the basis of inflammatory infiltrate, including the infiltration of connective tissue with macrophages at the base of the heart, surrounding the aortic valve and the atria.

Development of Macrophages and Their Homeostasis Is Not Affected in cd11b-dnp38 Transgenic Mice

Macrophages are the main infiltrating cell in the inflamed heart during infection with B. burgdorferi [27]. Because p38 MAP kinase inhibition reduced B. burgdorferi–induced carditis, we speculated that p38 MAP kinase activity in macrophages negatively regulates cardiac inflammation. We thus generated Tg mice expressing a mutant of p38 MAP kinase that has been previously shown to act as a dominant negative [31], expressed under the control of the CD11b promoter to target its expression to macrophages. The mice were backcrossed to the C3H/HeN background for >10 generations. The transgene was detected in the lung, thymus, and spleen (Figure 2A). BMMs were also tested by RT-PCR for the expression of the dnp38 transgene. The transgene was readily detected in BMMs generated from the Tg mice (Figure 2A).

The cd11b-dnp38 Tg mice developed normally and were born at the expected Mendelian ratio. They showed no signs of gross abnormalities. The expression of the transgene did not affect macrophage generation or homeostasis, as evidenced by flow cytometric analysis of splenic F4/80+ cells (Figure 2B). Macrophage percentages were similar in the Tg and NLC mice (Figure 2B). The levels of expression of CD11b and TLR2 were also equivalent in dnp38-Tg and NLC BMMs (Figure 2C). However, the stimulation of Tg BMMs with B. burgdorferi resulted in a significant reduction in the production of IL-6, compared to NLC BMMs (Figure 2D). Overall, these results show that the expression of the transgene does not affect macrophages development and homeostasis but regulates the induction of cytokines in response to B. burgdorferi stimulation.

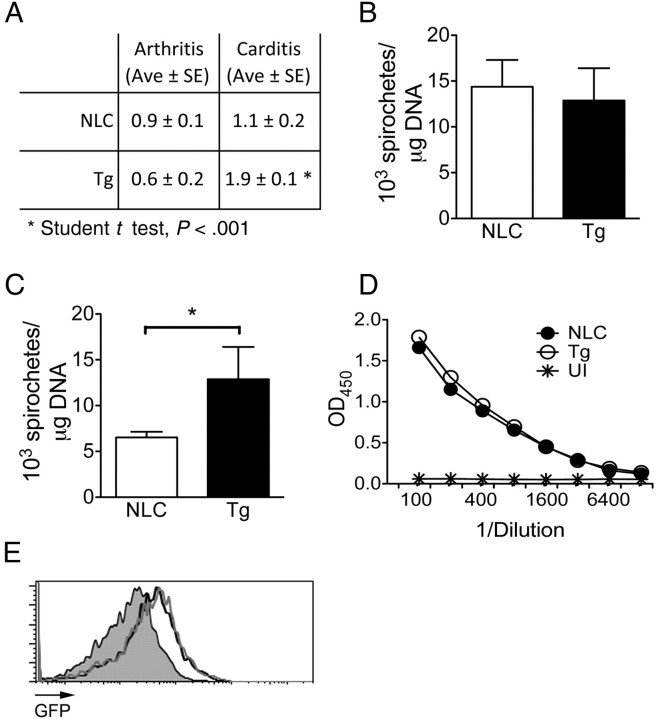

Increased Heart Pathology in cd11b-dnp38 Transgenic Mice Infected With B. burgdorferi

cd11b-dnp38 Tg mice were infected with B. burgdorferi and analyzed for cardiac and joint inflammation after 2 weeks of infection. Similar to the results obtained with SB203580, no significant differences were observed in arthritis severity between Tg and NLC mice (Figure 3A). In contrast, the degree of carditis was significantly higher in the Tg animals as compared to the controls (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Infection of cd11b-dnp38 transgenic (Tg) mice with Borrelia burgdorferi results in increased carditis. A, Arthritis and carditis in 2-week infected cd11b-dnp38 Tg and negative littermate control (NLC) mice. Groups of mice were infected with B. burgdorferi and analyzed for joint and cardiac inflammation. The results represent the average (Ave) ± standard error (SE) of X10 mice in 2 independent experiments. B. burgdorferi levels in the ear (B) and heart (C) of the Tg and NLC infected mice. The results represent the average ± SE of X10 mice in 2 independent experiments. TLR2, Toll-like receptor 2. D, B. burgdorferi–specific immunoglobulin G levels in the sera of Tg and NLC infected mice. Serial dilutions of murine sera were probed in a microtiter plate coated with 0.5 μg/mL of a B. burgdorferi lysate. OD, optical density; UI, uninfected NLC control. The results correspond to 5 mice per group and are representative of 2 experiments. E, Phagocytosis of GFP-expressing B. burgdorferi by BMMs of Tg mice (grey histogram) and NLC mice (black histogram). The cells were incubated at a multiplicity of infection of 10 for 4 hours, followed by washing and flow cytometry analysis. The grey-filled histogram represents the 4°C control.

We next determined spirochete levels in skin and heart tissue to assess the ability of the Tg mice to control infection. While the number of spirochetes in the ear tissue was equivalent between Tg and NLC mice (Figure 3B), the number of B. burgdorferi in the infected hearts of the Tg animals were significantly higher (Figure 3C). To determine whether the higher spirochetal numbers in the Tg mice were due to a differential antibody response, we measured the antibody titers specific for B. burgdorferi antigens in the infected Tg mouse sera. B. burgdorferi–specific sera IgG levels were indistinguishable between Tg and NLC infected mice (Figure 3D). We also determined the capacity of Tg BMMs to phagocytose B. burgdorferi to assess whether p38 MAP kinase regulates the capacity to eliminate the spirochete. BMMs generated from Tg mice internalized GFP-expressing B. burgdorferi as efficiently as NLC BMMs (Figure 3E), suggesting that the expression of the dnp38 transgene did not affect their intrinsic phagocytic capacity.

Infection of cd11b-dnp38 Tg Mice With B. burgdorferi Results in Reduced Levels of ifnγ Gene Expression in the Heart

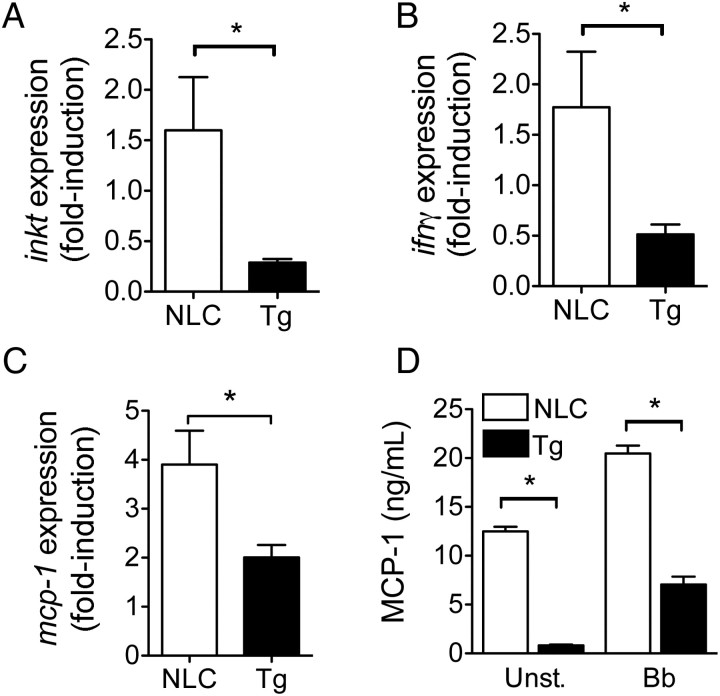

The production of IFN-γ by iNKT cells in the heart of infected mice increases the phagocytic activity of CD1d+ macrophages, resulting in enhanced bacterial clearance and reduced cardiac inflammation [8]. We measured iNKT cell infiltration of infected hearts by quantitative real-time PCR. Infected cd11b-dnp38 Tg mice had significantly fewer iNKT cells in the heart as compared to infected NLCs (Figure 4A). Uninfected mice did not contain iNKT cells in the heart, as reported elsewhere [8]. In correlation, the levels of ifnγ messenger RNA (mRNA) detected in the hearts of the infected mice were significantly reduced in the Tg mice (Figure 4B), confirming that iNKT cells are a significant source of the cytokine [8].

Figure 4.

Decreased invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cell infiltration and interferon γ (IFN-γ) production in the hearts of infected transgenic (Tg) mice. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of Tg (black bars) and negative littermate control (NLC; white bars) mouse heart messenger RNA (mRNA) for the quantification of vα14i-jα18 NKT cells (A) and ifnγ relative to actin expression (B). C, Relative expression of mcp-1 in the hearts of Tg and NLC infected mice. mRNA was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR with primers specific for mcp-1. The expression levels were determined relative to those of actin. The results in A–C represent the average ± standard error (SE) of 10 mice per group from 2 independent experiments. *P < .05, by the Student t test. D, Expression of MCP-1 by BMMs from Tg and NLC mice stimulated with B. burgdorferi (Bb; multiplicity of infection = 50) or left unstimulated (Unst.). The results represent the average ± SE of 1 experiment performed in triplicate and are representative of 2 experiments. *P < .05, by the Student t test.

The migration of iNKT cells to sites of infection or tumor implantation is governed by the local production of chemokines. The chemokine MCP-1 (ie, CCL-2) has been implicated in the translocation of iNKT cells to the lungs upon infection with Cryptococcus neoformans, as well as to tumors of diverse etiology [41–43]. We therefore analyzed the level of expression of the mcp-1 gene in the hearts of Tg and NLC infected mice. The levels of mcp-1 mRNA were significantly lower in B. burgdorferi–infected, Tg mice as compared to NLC mice (Figure 4C). Furthermore, BMMs in Tg mice secreted significantly lower basal levels of MCP-1 as compared to BMMs in NLC mice, as well as in response to B. burgdorferi stimulation in vitro (Figure 4D). These results show that p38 MAP kinase regulates the expression of MCP-1, the infiltration of iNKT cells to the heart, and the production of the protective cytokine IFN-γ.

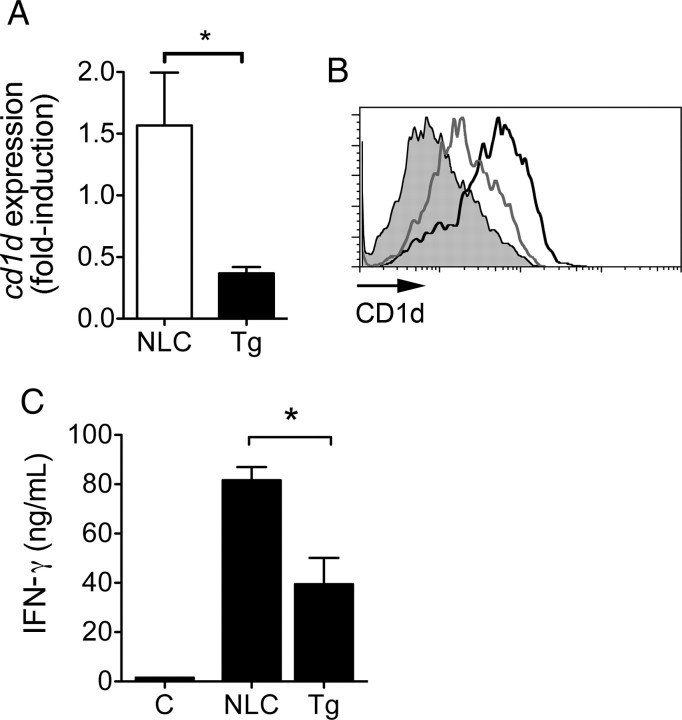

Expression of the dnp38 Transgene Results in Reduced Levels of CD1d in Macrophages

IFN-γ increases the expression of the antigen-presenting molecule CD1d in macrophages [8], leading to a positive feedback loop that further increases antigen presentation by CD1d+ macrophages. We analyzed the expression of CD1d in the cardiac tissue upon infection of the Tg mice. The expression levels of cd1d were significantly lower in the Tg mice, compared with the NLC mice (Figure 5A). To determine whether the lower expression levels of cd1d were due to the lower levels of IFN-γ in the infected tissue or, alternatively, due to p38 MAP kinase regulation of antigen-presenting molecule expression, we determined surface CD1d levels in Tg and NLC BMMs. The analysis of CD1d levels in BMMs by flow cytometry showed reduced surface levels in dnp38 macrophages (Figure 5B), indicating that p38 MAP kinase regulates cd1d expression, as reported elsewhere [44].

Figure 5.

Decreased expression of CD1d and invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cell activation in cd11b-dnp38 transgenic (Tg) mice. A, Relative expression of cd1d in the hearts of infected Tg and negative littermate control (NLC) mice. Messenger RNA was analyzed by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction, and the expression levels of cd1d were calculated relative to actin expression. The results represent the average ± standard error (SE) of 10 mice per group from 2 independent experiments. *P < .05, by the Student t test. B, Surface expression levels of CD1d in BMMs from Tg and NLC mice. BMMs were generated from Tg (grey histogram) and NLC (black histogram) mice and stained with a specific anti-CD1d monoclonal antibody, labeled with PE. The cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. The grey-filled histogram represents the isotype-labeled control. The result is representative of 3 experiments. C, Decreased production of interferon γ (IFN-γ) ex vivo by splenocytes from the cd11b-dnp38 Tg mice (black bar) as compared to NLC mice (white bar) treated with the prototypic iNKT antigen α-galactosylceramide (αGalCer). Groups of 5 mice were injected with 100 ng/g of αGalCer, and 12 hours later whole splenocytes were incubated ex vivo for 72 hours. IFN-γ levels were then determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay. *P < .05, by the Student t test.

We next assessed the functional effect of the expression of the dnp38 transgene in macrophages on the ability of iNKT cells to respond to the prototypical antigen, αGalCer. Groups of Tg and NLC mice were injected with αGalCer, and 12 hours later the level of IFN-γ produced by whole splenocytes was assessed ex vivo without further stimulation. The levels of INF-γ induced by αGalCer in Tg splenocytes were significantly reduced as compared to control cells (Figure 5C). Overall, these results demonstrated that p38 MAP kinase regulates the expression of CD1d and the ability of macrophages to present antigen and induce the activation of iNKT cells.

DISCUSSION

Cardiac inflammation during infection with B. burgdorferi involves the migration and activation of macrophages and other cell types, including invariant NKT cells and T cells. The production of IFN-γ predominantly by iNKT and other cell types ameliorates inflammation through the activation of macrophages [8, 36]. The interaction of macrophages and NKT cells involves feedback mechanisms between both cell types: macrophages present antigen to iNKT cells in the context of the antigen-presenting molecule CD1d, resulting in IFN-γ production; in turn, IFN-γ increases both the phagocytic activity of macrophages and the expression of CD1d, thereby increasing their capacity to present antigen to iNKT cells [8]. However, the factors that intrinsically regulate antigen presentation by macrophages and the infiltration of iNKTs to the infected heart remain poorly understood. The data presented here show that p38 MAP kinase activity regulates the development of cardiac, but not joint, inflammation upon infection with B. burgdorferi. These data support a role for p38 MAP kinase activity in the regulation of CD1d expression in macrophages, the migration and activation of iNKT cells, and the production of the protective cytokine IFN-γ. Our data also indicate that iNKT cell activation is critical for the control of cardiac inflammation in the C3H background, similar to what was observed in B6 mice [8]. These results also underline the differential etiology of inflammation occurring in the joints and the heart [45, 46].

p38 MAP kinase regulates the expression of IFN-γ by iNKT cells in response to αGalCer through a mechanism that involves the kinase MNK1 and the elongation factor eIF-4e [47]. We now demonstrate another level of control of iNKT cell activation controlled by the kinase through the regulation of the production of the chemokine MCP-1, as well as through antigen presentation mediated by CD1d. The results using the specific p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580 are consistent with a central role of the kinase in the control of cardiac inflammation during infection with the spirochete. Importantly, however, these data indicate that the activity of the MAP kinase in infiltrating macrophages critically regulates both the infiltration and activation of NKT cells.

The recruitment of iNKT cells to sites of inflammation or tumors occurs through the expression of chemokines. Several studies have shown that the chemokine MCP-1 (ie, CCL-2) regulates the infiltration of these cells to inflamed tissues and tumors [41–43], although MCP-1 has been classically associated with the migration of monocytes [48]. Our results show that in response to the spirochete, macrophages produce MCP-1 in a p38 MAP kinase–dependent manner. Thus, dnp38 BMMs produce significantly lower levels of the chemokine in vitro. Importantly, the expression of mcp-1 in the infected hearts of Tg mice is significantly reduced as compared to that in controls. Overall, our results support a model in which the colonization of B. burgdorferi–infected cardiac tissue by macrophages results in p38 MAP kinase–dependent production of MCP-1 and iNKT recruitment. Our results also show that p38 MAP kinase also regulates CD1d expression and antigen presentation to iNKT cells, resulting in the production of the protective cytokine IFN-γ. p38 MAP kinase therefore plays a critical role during the development of the immune response to B. burgdorferi.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We are grateful to Daniel G. Tenen for providing the cd11b promoter.

Financial support. This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant (AR 048265 to J. A.), a UMass Amherst Faculty Research Grant (to J. A.), and a fellowship from the American Heart Association to (C. M. J. O.).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Wooten RM, Ma Y, Yoder RA, et al. Toll-like receptor 2 is required for innate, but not acquired, host defense to Borrelia burgdorferi. J Immunol. 2002;168:348–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behera AK, Hildebrand E, Uematsu S, Akira S, Coburn J, Hu LT. Identification of a TLR-independent pathway for Borrelia burgdorferi-induced expression of matrix metalloproteinases and inflammatory mediators through binding to integrin α3β1. J Immunol. 2006;177:657–64. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirschfeld M, Kirschning CJ, Schwandner R, et al. Cutting edge: inflammatory signaling by Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins is mediated by toll-like receptor 2. J Immunol. 1999;163:2382–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ebnet K, Brown KD, Siebenlist UK, Simon MM, Shaw S. Borrelia burgdorferi activates nuclear factor-kappa B and is a potent inducer of chemokine and adhesion molecule gene expression in endothelial cells and fibroblasts. J Immunol. 1997;158:3285–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anguita J, Barthold SW, Persinski R, et al. Murine Lyme arthritis development mediated by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activity. J Immunol. 2002;168:6352–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Defosse DL, Johnson RC. In vitro and in vivo induction of tumor necrosis factor alpha by Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1109–13. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.1109-1113.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma Y, Weis JJ. Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface lipoproteins OspA and OspB possess B-cell mitogenic and cytokine-stimulatory properties. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3843–53. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.9.3843-3853.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olson CM, Jr, Bates TC, Izadi H, et al. Local production of IFN-γ by invariant NKT cells modulates acute Lyme carditis. J Immunol. 2009;182:3728–34. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ip YT, Davis RJ. Signal transduction by the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)—from inflammation to development. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:205–19. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitmarsh AJ, Davis RJ. Transcription factor AP-1 regulation by mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways. J Mol Med. 1996;74:589–607. doi: 10.1007/s001090050063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raingeaud J, Gupta S, Rogers JS, et al. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and environmental stress cause p38 mitogen- activated protein kinase activation by dual phosphorylation on tyrosine and threonine. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7420–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Derijard B, Raingeaud J, Barrett T, et al. Independent human MAP-kinase signal transduction pathways defined by MEK and MKK isoforms. Science. 1995;267:682–5. doi: 10.1126/science.7839144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han J, Lee JD, Jiang Y, Li Z, Feng L, Ulevitch RJ. Characterization of the structure and function of a novel MAP kinase kinase (MKK6) J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2886–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moriguchi T, Kuroyanagi N, Yamaguchi K, et al. A novel kinase cascade mediated by mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 6 and MKK3. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13675–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raingeaud J, Whitmarsh AJ, Barrett T, Derijard B, Davis RJ. MKK3- and MKK6-regulated gene expression is mediated by the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1247–55. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freshney NW, Rawlinson L, Guesdon F, et al. Interleukin-1 activates a novel protein kinase cascade that results in the phosphorylation of Hsp27. Cell. 1994;78:1039–49. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90278-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olson CM, Hedrick MN, Izadi H, Bates TC, Olivera ER, Anguita J. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase controls NF-κB transcriptional activation and tumor necrosis factor alpha production through RelA phosphorylation mediated by mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1 in response to Borrelia burgdorferi antigens. Infect Immun. 2007;75:270–7. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01412-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han J, Lee JD, Bibbs L, Ulevitch RJ. A MAP kinase targeted by endotoxin and hyperosmolarity in mammalian cells. Science. 1994;265:808–11. doi: 10.1126/science.7914033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JC, Laydon JT, McDonnell PC, et al. A protein kinase involved in the regulation of inflammatory cytokine biosynthesis. Nature. 1994;372:739–46. doi: 10.1038/372739a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mavunkel BJ, Chakravarty S, Perumattam JJ, et al. Indole-based heterocyclic inhibitors of p38α MAP kinase: designing a conformationally restricted analogue. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:3087–90. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00653-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anand P, Shenoy R, Palmer JE, et al. Clinical trial of the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor dilmapimod in neuropathic pain following nerve injury. Eur J Pain. 2011;15:1040–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Genovese MC, Cohen SB, Wofsy D, et al. A 24-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group study of the efficacy of oral SCIO-469, a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor, in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:846–54. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yasuda S, Sugiura H, Tanaka H, Takigami S, Yamagata K. p38 MAP kinase inhibitors as potential therapeutic drugs for neural diseases. Cent Nerv Syst Agents Med Chem. 2011;11:45–59. doi: 10.2174/187152411794961040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rincon M, Davis RJ. Regulation of the immune response by stress-activated protein kinases. Immunol Rev. 2009;228:212–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Armstrong AL, Barthold SW, Persing DH, Beck DS. Carditis in Lyme disease susceptible and resistant strains of laboratory mice infected with Borrelia burgdorferi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;47:249–58. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barthold SW, Beck DS, Hansen GM, Terwilliger GA, Moody KD. Lyme borreliosis in selected strains and ages of laboratory mice. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:133–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruderman EM, Kerr JS, Telford SR, Spielman A, Glimcher LH, Gravallese EM. Early murine Lyme carditis has a macrophage predominance and is independent of major histocompatibility complex class II-CD4+ T cell interactions. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:362–70. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.2.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zimmer G, Schaible UE, Kramer MD, Mall G, Museteanu C, Simon MM. Lyme carditis in immunodeficient mice during experimental infection of Borrelia burgdorferi. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1990;417:129–35. doi: 10.1007/BF02190530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hedrick MN, Olson CM, Jr, Conze DB, Bates TC, Rincon M, Anguita J. Control of Borrelia burgdorferi-specific CD4+ T-cell effector function by interleukin-12- and T-cell receptor-induced p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activity. Infect Immun. 2006;74:5713–7. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00623-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dziennis S, Van Etten RA, Pahl HL, et al. The CD11b promoter directs high-level expression of reporter genes in macrophages in transgenic mice. Blood. 1995;85:319–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rincón M, Enslen H, Raingeaud J, et al. Interferon-gamma expression by Th1 effector T cells mediated by the p38 MAP kinase signaling pathway. EMBO J. 1998;17:2817–29. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.10.2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pal U, Wang P, Bao F, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi basic membrane proteins A and B participate in the genesis of Lyme arthritis. J Exp Med. 2008;205:133–41. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barthold SW, Hodzic E, Tunev S, Feng S. Antibody-mediated disease remission in the mouse model of lyme borreliosis. Infect Immun. 2006;74:4817–25. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00469-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bolz DD, Sundsbak RS, Ma Y, et al. MyD88 plays a unique role in host defense but not arthritis development in Lyme disease. J Immunol. 2004;173:2003–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X, Ma Y, Weis JH, Zachary JF, Kirschning CJ, Weis JJ. Relative contributions of innate and acquired host responses to bacterial control and arthritis development in Lyme disease. Infect Immun. 2005;73:657–60. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.657-660.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bockenstedt LK, Kang I, Chang C, Persing D, Hayday A, Barthold SW. CD4+ T helper 1 cells facilitate regression of murine Lyme carditis. Infect Immun. 2001;69:5264–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5264-5269.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morrison TB, Ma Y, Weis JH, Weis JJ. Rapid and sensitive quantification of Borrelia burgdorferi-infected mouse tissues by continuous fluorescent monitoring of PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:987–92. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.987-992.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Motameni AR, Bates TC, Juncadella IJ, Petty C, Hedrick MN, Anguita J. Distinct bacterial dissemination and disease outcome in mice subcutaneously infected with Borrelia burgdorferi in the midline of the back and the footpad. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2005;45:279–84. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunham-Ems SM, Caimano MJ, Pal U, et al. Live imaging reveals a biphasic mode of dissemination of Borrelia burgdorferi within ticks. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3652–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI39401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blander JM, Medzhitov R. Regulation of phagosome maturation by signals from toll-like receptors. Science. 2004;304:1014–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1096158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nowak M, Arredouani MS, Tun-Kyi A, et al. Defective NKT cell activation by CD1d+ TRAMP prostate tumor cells is corrected by interleukin-12 with alpha-galactosylceramide. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song L, Ara T, Wu HW, et al. Oncogene MYCN regulates localization of NKT cells to the site of disease in neuroblastoma. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2702–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI30751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawakami K, Kinjo Y, Uezu K, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1-dependent increase of V alpha 14 NKT cells in lungs and their roles in Th1 response and host defense in cryptococcal infection. J Immunol. 2001;167:6525–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Renukaradhya GJ, Webb TJ, Khan MA, et al. Virus-induced inhibition of CD1d1-mediated antigen presentation: reciprocal regulation by p38 and ERK. J Immunol. 2005;175:4301–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anguita J, Barthold SW, Samanta S, Ryan J, Fikrig E. Selective anti-inflammatory action of interleukin-11 in murine Lyme disease: arthritis decreases while carditis persists. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:734–7. doi: 10.1086/314613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown CR, Blaho VA, Fritsche KL, Loiacono CM. Stat1 deficiency exacerbates carditis but not arthritis during experimental lyme borreliosis. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2006;26:390–9. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.26.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagaleekar VK, Sabio G, Aktan I, et al. Translational control of NKT cell cytokine production by p38 MAPK. J Immunol. 2011;186:4140–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yadav A, Saini V, Arora S. MCP-1: chemoattractant with a role beyond immunity: a review. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:1570–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]