Dendrimers and other 3-D molecular assemblies are attractive scaffolds for biological delivery agents and diagnostic probes[1,2] due to their globular shape, modular structure, monodispersity and plurality of functional end groups.[3] To address this potential, a number of strategies and related dendritic architectures have been developed for delivery of bioactive molecules to desired cells or tissue,[4] with encapsulation[5] and covalent attachment to the dendritic chain ends being two major approaches.[6] While the encapsulation of drugs or dyes within the inner cavities of the dendrimer is promising,[5] in most cases only a limited number of guest molecules can be encapsulated even with dendrimers of high generations.[4d] Moreover, the non-covalent nature of the encapsulation makes it a challenge to control the stability of the loaded carrier and subsequent release of the payload.[4e] An alternative strategy exploits the large number of dendritic chain ends to carry the cargo molecules.[6] However, loading of large amounts of hydrophobic drugs or dyes can alter the dendrimer surface properties and decrease its solubility and bio-compatibility.[7] Partial functionalization[8] alleviates this issue but results in random chain end modification leading to a dispersity in loading, variable bio-performance and in many cases only low degrees of surface functionalization can be achieved without significantly changing the surface properties.[9]

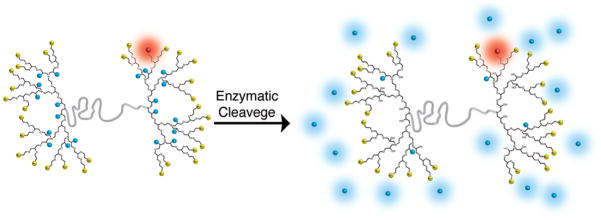

In order to maintain both high loading and mono-dispersity, an alternative design is to covalently attach the cargo molecules to the interior of the dendrimer.[10] This strategy overcomes the challenges associated with surface functionalization, allowing high and reproducible loading without significantly altering the surface properties of the dendritic scaffold. To illustrate the power of this novel strategy, we report an accelerated synthesis of orthogonal surface and internally functionalized dendrimers[11] and their application as multi-functional dendritic scaffolds (Figure 1). As model delivery and diagnostic units, two different dyes were conjugated to the dendrimer: multiple coumarin units (blue in figure) were loaded internally through a cleavable linker and a single Alexa647 dye (red in figure) was conjugated to the surface through a stable amide bond. This dual labelling allows the dendritic scaffold and the model payload to be individually tracked in living cells at the same time. An additional facet of the platform design is the presence of numerous protonated amino groups at the chain ends of the dendritic fragments (yellow in figure), which are designed to induce cell internalization through endocytosis and while cationic materials may be toxic, they serve as a useful model system. Once inside the cell, it is envisaged that hydrolytic enzymes would cleave the internal coumarin units from the scaffold, resulting in release of the model coumarin payload and appearance of fluorescence.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the modular design of dendritic scaffolds with protonated amino groups at the chain ends for cellular uptake (yellow). Upon enzymatic cleavage, the covalently attached, internal “blue” dyes are released while the non-cleavable “red” dye allows for monitoring of the dendrimer itself.

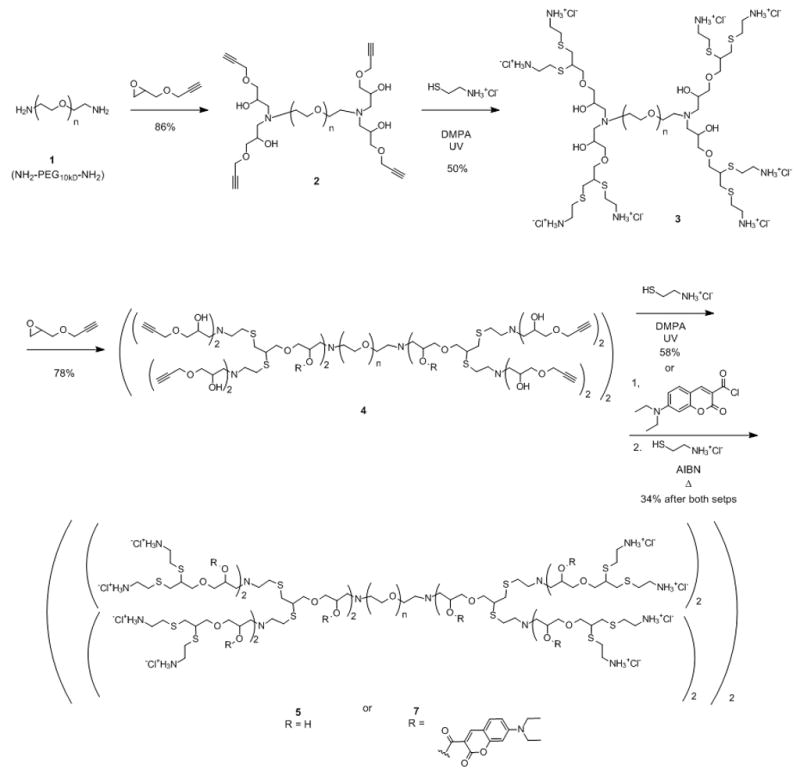

The numerous structural requirements for these multi-functional dendritic scaffolds necessitated the development of an alternating sequence of ‘amine-epoxy’ and ‘thiol-yne’ coupling reactions (Scheme 1). In contrast to traditional thiol-ene chemistry used previously,[11] thiol-yne coupling leads to the addition of two thiols across the triple bond which, when combined with amine-epoxy chemistry, results in accelerated generation growth at each step of the synthesis (an AB2/CD2 approach)[12a] with the internal hydroxyl groups being carried through the synthesis without the need for protection/deprotection chemistry.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic strategy for the synthesis of internally functionalized, hybrid dendritic macromolecule, [G-4]-(coumarin)20 7, based on a 10 kDa PEG core.

The starting material was a 10kDa bis-amine chain end terminated polyethylene glycol (PEG), 1, which functions as a core[12b] to enhance water solubility of the dendritic scaffold while also serving as a soluble support, simplifying purification of these hybrid dendritic-linear macromolecules.[13] The initial reaction involves the addition of propargyl glycidyl ether, to the PEG-diamine, 1, to give the tetra-alkyne, 2, which on thiol-yne coupling[14] with cysteamine hydrochloride gives the second generation, octaamine, 3. Repetition of this 2-step procedure then gives the corresponding 4th generation macromolecule which contains 20 internal hydroxyl groups and 32 primary amino groups at the chain ends, 5. Alternatively, functionalization of the internal hydroxyl groups was performed at the terminal alkyne stage of the synthesis (i.e. 4) through facile esterification with an excess of 7-(diethylamino)coumarin-3-carbonyl chloride. The internally functionalized derivative, 6, was dialyzed to remove excess coumarin, followed by thermal thiol-yne coupling with cysteamine hydrochloride in the presence of AIBN to give the hybrid dendritic structure, [G-4]-(coumarin)20 7, which was shown by 1H-NMR to contain ca. 20 coumarin units attached to the internal hydroxyl groups. A combination of NMR spectroscopy, MALDI mass spectroscopy and GPC allowed full structural characterization of these novel functionalized, hybrid dendritic-linear macromolecules.

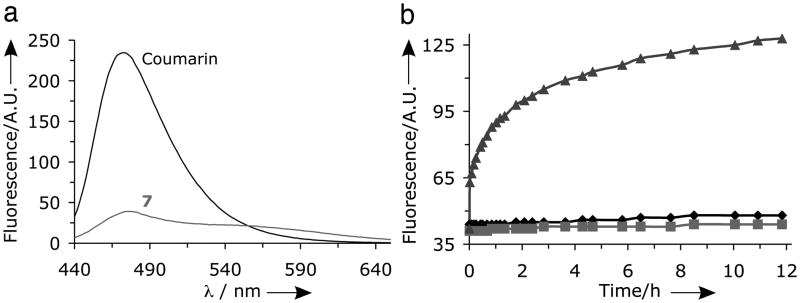

The core-shell structure of the labelled dendritic-linear macromolecules was initially examined by fluorescence spectroscopy, which showed significant quenching for the dendrimer-bonded coumarin (Figure 2a) when compared to the corresponding small molecule. This quenching of fluorescence is due to the high local concentration of coumarin groups attached to the interior of the dendrimer[6a,15] and on release of the model coumarin payload, the fluorescence should be restored. To demonstrate that the covalently attached dyes inside the dendrimer are accessible to enzymes, and therefore susceptible to enzymatic cleavage, functionalized dendrimer 7 was incubated with Porcine Liver Esterase (PLE).[16] A kinetic plot of the maximum intensity at 480 nm as a function of time is presented in figure 2b and shows a significant increase in fluorescence only in the presence of PLE.

Figure 2.

Fluorescence spectra of (a) free coumarin and [G-4]-(Coumarin)20, 7; (b) Fluorescence intensity of 7 at 480 nm as a function of time in the presence of esterase at pH 7.4 (▲) and in the absence of esterase at pH = 5.0 (

) and 7.4 (◆).

) and 7.4 (◆).

This implies that PLE can access and hydrolyze the internal ester bonds connecting the coumarin units to the dendritic scaffold with only minor cleavage being observed at pH 5.0 or 7.4. The cleavage of the internal coumarin units were also confirmed by HPLC experiments which showed release only in the presence of esterase (see SI). The dequenching of the coumarin dye after release is of crucial importance for the cell studies as it provides insight into ester bond cleavage inside living cells while also allowing independent tracking of the payload and the scaffold.

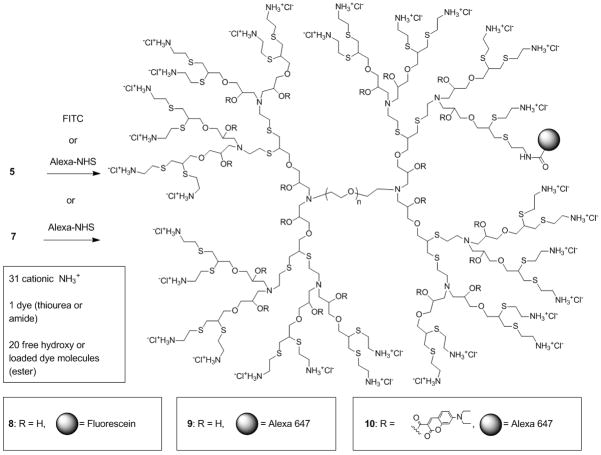

Having demonstrated the increase in fluorescence on payload release, a series of model compounds were prepared for in-vitro experiments and to examine the internalization of these hybrid structures into living cells.[17] For tracking of the dendritic scaffold, the amino functionalized dendrimer 5 was conjugated with an average of one FITC dye to yield the labelled 4th generation dendrimer, 8. Alternatively, Alexa647 was coupled with the dendrimers 5 and 7 to yield the labelled derivatives, [G-4]-Alexa, 9, and [G-4]-(Coumarin)20-Alexa, 10, respectively, each having an average of one Alexa dye at the chain ends and in the latter case, ~20 coumarin units were also attached to the internal dendrimer framework.

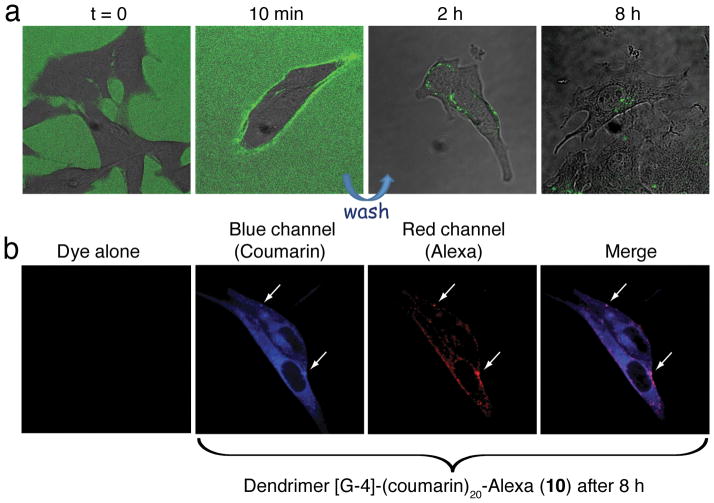

To understand the internalization and intracellular trafficking of the unloaded dendritic carrier with internal hydroxyl groups, B16 mouse melanoma or HeLa cells were incubated with [G-4]-FITC, 8, at 37 °C and 4 °C. Subcellular confocal fluorescence microscopy images reveals membrane binding at both temperatures but internalization only occurs at 37 °C. The cells were then washed to remove excess dendrimer with the formation of endocytic vesicles observed at ca. 2 hours and final intracellular targeting to the perinuclear region in about 8 hours at 37 °C. Similar results were obtained for the corresponding Alexa647-labeled dendrimer, [G-4]-Alexa 9 (see SI).

This behavior is in agreement with previously reported results for the internalization of cationic PAMAM dendrimers, suggesting that after endocytosis the dendrimer is delivered to the lysosome.[18] Having verified the internalization of the hybrid dendritic scaffold, the B16 cells were incubated with the internally functionalized [G-4]-(Coumarin)20-Alexa dendrimer, 10, which allows both the dendritic scaffold and the coumarin payload to be tracked at the same time. While the dye alone, showed no internalization, indicating that it is not membrane permeable in its free form, the images of dye-loaded dendrimer show coumarin release inside the cells; a blue fluorescence signal is observed in the cytoplasm and this signal intensity increases over a period of 8 hours (Figure 3b). The red signal from Alexa647 dye indicates that the dendritic scaffold is localized only inside endocytic vesicles, probably due to its large size and hydrophilicity and is not able to escape the vesicle membrane. Significantly, colocalization between the blue (payload) and red (scaffold) signals in the vesicles was observed (Figure 3b and SI), indicating that the coumarin units are released from the dendrimer before escaping the vesicles. Additionally, the payload carrying scaffold, [G-4]-(Coumarin)20-Alexa dendrimer, 10, displays a slightly slower internalization rate in comparison to labeled derivative with no functionalization of the internal hydroxyl groups, [G-4]-Alexa 9. This can be attributed to the more hydrophobic interior due to the presence of the internal coumarin units. These results demonstrate the power of this dual functionalization strategy in providing well-defined delivery systems, which allow for fundamental insights into the intra-cellular behavior of both scaffolds and their payloads.

Figure 3.

Subcellular confocal images of B-16 cells treated with (A) dendrimer [G-4]-FITC, 8, (green) and (B) dendrimer [G-4]-(Coumarin)20-Alexa, 10, (coumarin –blue and Alexa – red) at 8 hours.

In summary, we have introduced a novel strategy for the facile synthesis of orthogonally functionalized hybrid dendritic-linear delivery systems, incorporating reactive groups at the chain ends as well as internally, through a combination of ‘amine-epoxy’ and ‘thiol-yne’ click chemistry. Starting from bis-amino-PEG, a 4th generation dendritic scaffold having chain end amino groups, a single FITC or Alexa dye and 20 internal coumarin units could be prepared. Even with this high loading of coumarin units (~25 wt%), confocal microscopy on living cells revealed that upon membrane binding and internalization of the scaffold, intracellular enzymes cleaved the coumarin payload, allowing release into the cytoplasm. As a result, both the dendritic scaffold and the release of its payload can be monitored simultaneously inside living cells.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of labelled dendrimers [G-4]-FITC, 8, [G-4]-Alexa, 9 and [G-4]-(Coumarin)20-Alexa, 10

Footnotes

This material is based upon work supported by the National Institutes of Health as a Program of Excellence in Nanotechnology (HHSN268201000046C). This work was partially supported by the MRSEC Program of the National Science Foundation through the MRL Central Facilities, the Research Experience for Teachers program (DMR 05-20415) and by fellowship support from Samsung (TK).

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

Contributor Information

Dr. Roey J. Amir, Materials Research Laboratory, University of California Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA 93106-5121, USA, Fax: (+1-805) 893-8797

Lorenzo Albertazzi, Email: l.albertazzi@sns.it, Materials Research Laboratory, University of California Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA 93106-5121, USA, Fax: (+1-805) 893-8797. NEST, Scuola Normale Superiore and CNR-INFM, and IIT@NEST, Center for Nanotechnology Innovation, Piazza San Silvestro 12, 56126 Pisa, Italy.

Jenny Willis, Materials Research Laboratory, University of California Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA 93106-5121, USA, Fax: (+1-805) 893-8797.

Prof. Anzar Khan, Department of Materials, Institute of Polymers, ETH-Zurich, Wolfgang-Pauli-Strasse 10, HCl H-520, 8093 Zurich Switzerland

Taegon Kang, Materials Research Laboratory, University of California Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA 93106-5121, USA, Fax: (+1-805) 893-8797.

Prof. Craig J. Hawker, Email: hawker@mrl.ucsb.edu, Materials Research Laboratory, University of California Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA 93106-5121, USA, Fax: (+1-805) 893-8797

References

- 1.Tomalia DA, Reyna LA, Svenson S. Biochem Soc T. 2007;35:61–67. doi: 10.1042/BST0350061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Gillies ER, Frèchet JMJ. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:35–43. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wu W, Hsiao SC, Carrico ZM, Francis MB. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2009;48:9493–9497. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Rosen BM, Peterca M, Huang C, Zeng X, Ungar G, Percec V. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2010;49:7002–7005. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lee C, MacKay JA, Frechet JMJ, Szoka FC. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1517–1526. doi: 10.1038/nbt1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Killops KL, Campos LM, Hawker CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5062–5064. doi: 10.1021/ja8006325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Venditto VJ, Allred K, Allred CD, Simanek EE. Chem Comm. 2009:5541–5542. doi: 10.1039/b911353c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Morgan MT, Nakanishi Y, Kroll DJ, Griset AP, Carnahan MA, Wathier M, Oberlies NH, Manikumar G, Wani MC, Grinstaff MW. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11913–11921. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Galeazzi S, Hermans TM, Paolino M, Anzini M, Mennuni L, Giordani A, Caselli G, Makovec F, Meijer EW, Vomero S, Cappelli A. Biomacromolecules. 2010:182–186. doi: 10.1021/bm901055a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Radowski MR, Shukla A, von Berlepsch H, Bottcher C, Pickaert G, Rehage H, Haag R. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2007;46:1265–1269. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Shabat D. J Polym Sci, Part A: Polym Chem. 2006;44:1569–1578. [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Moorefield CN, Newkome GR. CR Chim. 2003;6:715–724. [Google Scholar]; b) D’Emanuele A, Attwood D. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57:2147–2162. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Almutairi A, Guillaudeu S, Berezin M, Achilefu S, Frèchet JMJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:444–445. doi: 10.1021/ja078147e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Crampton HL, Simanek EE. Polym Int. 2007;56:489–496. doi: 10.1002/pi.2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Langereis S, de Lussanet QG, van Genderen MHP, Meijer EW, Beets-Tan RGH, Griffioen AW, van Engelshoven JMA, Backes WH. NMR Biomed. 2006;19:133–141. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Lee C, Gillies ER, Fox ME, Guillaudeu SJ, Frèchet JMJ, Dy EE, Szoka FC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16649–16654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607705103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Hourani R, Jain M, Maysinger D, Kakkar A. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:6164–6168. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duncan R, Izzo L. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57:2215–2237. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Waddell JN, Mullen DG, Orr BG, Banaszak Holl MM, Sander LM. Phys Rev E. 2010;82:036108. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.82.036108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kurtoglu YE, Navath RS, Wang B, Kannan S, Romero R, Kannan RM. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2112–2121. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Mullen DG, Borgmeier EL, Desai AM, van Dongen MA, Barash M, Cheng X-m, Baker JJR, Banaszak Holl MM. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:10675–10678. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Mullen DG, Borgmeier EL, Fang M, McNerny DQ, Desai AM, Baker JJR, Orr BG, Banaszak Holl MM. Macromolecules. 2010;43:6577–6587. doi: 10.1021/ma100663c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurtoglu YE, Mishra MK, Kannan S, Kannan RM. Int J Pharmaceut. 2010;384:189–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antoni P, Hed Y, Nordberg A, Nyström D, Von Holst H, Hult A, Malkoch M. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2009;48:2126–2130. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang T, Amir RJ, Khan A, Ohshimizu K, Hunt J, Sivanandan K, Montañez M, Malkoch M, Ueda M, Hawker CJ. Chem Comm. 2010;46:1556–1158. doi: 10.1039/b921598k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antoni P, Nystrom D, Hawker CJ, Hult A, Malkoch M. Chem Comm. 2007;22:2249–2251. doi: 10.1039/b703547k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Degoricija L, Carnahan MA, Johnson CS, Kim T, Grinstaff MW. Macromolecules. 2006;39:8952–8958. [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Okuro K, Kinbara K, Takeda K, Inoue Y, Ishijima A, Aida T. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2010;49:3030–3033. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kim TI, Seo HJ, Choi JS, Jang HS, Baek J, Kim K, Park JS. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:2487–2492. doi: 10.1021/bm049563j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Hoogenboom R. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2010;49:3415–3417. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hoyle CE, Bowman CN. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2010;49:1540–1573. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wängler C, Moldenhauer G, Saffrich R, Knapp EM, Beijer B, Schnölzer M, Wängler B, Eisenhut M, Haberkorn U, Mier W. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:8116–8130. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azagarsamy MA, Sokkalingam P, Thayumanavan S. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:14184–14185. doi: 10.1021/ja906162u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sisson AL, Steinhilber D, Rossow T, Welker P, Licha K, Haag R. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2010;49:7540–7575. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albertazzi L, Serresi M, Albanese A, Beltram F. Mol Pharm. 2010;7:680–688. doi: 10.1021/mp9002464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.