Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of stressful life events (SLE on medication adherence (3 day, 30 day) as mediated by sense of coherence (SOC), self-compassion (SCS), and engagement with the health care provider (eHCP) and whether this differed by international site. Data were obtained from a cross-sectional sample of 2082 HIV positive adults between September 2009 and January 2011 from sites in Canada, China, Namibia, Puerto Rico, Thailand and the U.S. Statistical tests to explore the effects of stressful life events on antiretroviral medication adherence included descriptive statistics, multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis, and path analysis. An examination by international site of the relationships between SLE, SCS, SOC and eHCP with adherence (3 day, 30 day) indicated these combined variables were related to adherence whether 3 day or 30 day to different degrees at the various sites. SLE, SCS, SOC, and eHCP were significant predictors of adherence past 3 days for the U.S (p= <.001), Canada (p= .006), and Namibia (p= .019). The combined independent variables were significant predictors of adherence past 30 days only in the U.S. and Canada.

Engagement with the provider was a significant correlate for antiretroviral adherence in most, but not all, of these countries. Thus the importance of eHCP cannot be overstated. Nonetheless, our findings need to be accompanied by the caveat that research on variables of interest while enriched by a sample obtained from international sites, may not have the same relationships in each country. Mediators of antiretroviral adherence: a multisite international study

Keywords: adherence, stressful life events, sense of coherence, self compassion, engagement with the provider, HIV/AIDS

Introduction

Adherence to antiretroviral (ARV) medications has been of concern to healthcare providers (HCP) since the first antiretroviral medication became available in 1986 (Volberding, 1989). The emphasis on taking Zidovudine every four hours was to prolong life (Fischl, et al., 1987). Studies demonstrating that an undetectable viral load decreases HIV transmission transformed ARV adherence to a public health priority (Anglemyer, Rutherford, Egger, & Siegfried, 2011; Cohen, Shaw, McMichael & Haynes, 2011; Vaughn, Wagner, Miyashiro, Ryan & Scott, 2011). The urgency with which optimal adherence must occur is amplified when governments expend resources for a “test and treat” approach to prevention (Cohen, Chen, et. al., 2011; Montaner, 2011).

Antiretroviral adherence has been demonstrated to be essential for optimal viral suppression (Alakija Kazeem, Fadeyl, Ogunmodede, & Desalu, 2010). Adherence above 90% has been associated with better physical function, general health, vitality, social functioning, mental health, and higher CD4 count (Wang, et al., 2009). Researchers have shown that stressful life events (SLE) have a negative impact on medication adherence and quality of life (QOL) (Bottonari, Safren, McQuaid, Hsiao, & Roberts, 2010; Sayles, Wong, Kinsler, Martins, & Cunningham, 2009; Tosevski & Milovancevic, 2006). Leserman, Ironson, O’Cleirigh, Fordiani, and Balbin (2008) found that “those with three or more stressful life events in the previous six months were 2.5 to 3 times more likely to be non-adherent” to ARV medications (p. 403). The evidence indicates that SLEs have a significant influence on overall sense of well-being.

Sense of coherence (SOC), reflects “an individual’s overall wellbeing and ability to cope with stress” (Pham, Vinck, Kinkodi, & Weinstein, 2010, p. 313), and lower SOC and health-related QOL were associated (p < 0.05 to < 0.001) in HIV-infected patients (Langius-Eklof, Lidman, & Wredling, 2009). SOC influences QOL but does not address the degree of self-compassion (SCS) that an individual has for him/herself.

Self-compassion was defined by Neff (2003) as “being kind and understanding toward oneself in instances of pain or failure rather than being harshly self-critical----“(p. 223). Subsequently, Neff, Rude and Kirkpatrick (2007) found SCS associated with happiness (r=.57) and optimism (r=.62). Heffernan, Griffin, McNulty, & Fitzpatrick (2010) observe that the elements of SCS include common humanity, self-kindness and mindfulness.

Optimal ARV adherence is facilitated by positive relationships with the healthcare provider (HCP) (Bakken, et al., 2000; Demmer, 2003; Sandelowski, Voils, Chang, & Lee. 2009; Schneider, Kaplan, Greenfield, Li & Wilson, 2004). Further, Johnson and colleagues (2006) demonstrated the importance of adherence self-efficacy as mediating the relationship between the HCP and adherence. In the current study, we investigated whether SOC, SCS and engagement with the HCP (eHCP), mediated the effects of SLEs on ARV adherence (3 day, 30 day) and whether this differed by international site.

Social Action Theory (SAT), with its’ emphasis on self-protective behavior, served as the theoretical foundation for this study (Ewart, 1991; Johnson, Carrico, Chesney, & Morin, 2008; Traube, Holloway & Smith, 2011). SAT hypothesizes that both individual level psychological factors and external environmental factors affect individual health behavior and public health priorities including ARV adherence. Possible covariates based on the literature review included (a) age, (b) gender, (c) ethnicity, (d) education, (e) country (international data collection site), (f) work for pay, and (g) AIDS status.

Method

Research design

This study is part of a multi-site cross-sectional investigation that examined the role of SCS, self-efficacy and self-esteem for HIV-positive individuals. Participants were recruited from fourteen sites in the United States (Boston; Chicago; Cleveland; Corpus Christi; Durham, (NC); Harlington, (TX); Newark; New York; San Francisco (3 sites); Seattle (2 sites); and Wilmington (NC), as well as one site each from Canada, China, Namibia, Puerto Rico and Thailand. These sites included HIV clinics, community-based organizations, medical centers, social service agencies, government hospitals, and an ARV clinic. Study eligibility included: 18 years or older, HIV-positive, able to provide informed consent, and site-specific language ability. There was no requirement that participants be on antiretroviral therapy. The study was administered in English at most US sites and in Canada; Chinese in China; English, Oshiwambi, Afrikaans or Otjiherero in Namibia; Spanish in Puerto Rico and Texas; and Thai in Thailand. People were excluded from the study if there was evidence of cognitive impairment, active psychosis, or significant confusion. Data were collected between September 2009 and January 2011 by self-administered questionnaires, with support provided by assistants as needed; computer assisted self-interview (China); or one-to-one interview (Bangkok, Newark, Namibia, Wilmington) (Webel, et al., 2011).

Protection of Human Subjects

The University of California-San Francisco (UCSF) secured approval for the overall study. Approval was obtained by each site director from their Protection of Human Subjects Committee and included approval for data-sharing with the central data repository at UCSF. Code numbers were used to protect the confidentiality of the research participants.

Instruments

Demographic Questionnaire

This instrument consists of 20 items concerning such demographic questions as age, gender, ethnicity, education, work for pay as well as queries about CD4 count, viral load, other health conditions as well as other illness characteristics (Wantland, et al., 2007).

Stressful Life Events

This 20 item instrument was modified from the List of Threatening Experiences Questionnaire (LTE-Q) (Brugha, Bebbington, Tennant & Hurry, 1985) that queried whether events occurred (Yes/No) in the last six or three months. Holzemer (2005) revised the questionnaire, adding eight items relevant to persons with HIV/AIDS to create the 20-item Stressful Life Events Questionnaire (SLE-Q) changing the time frame to one month. The SLE-Q measures the experience of SLE such as serious illness, injury, death of a parent or spouse, unemployment, and stigma and scores can range from 0–20. The Cronbach’s alpha (a measure of the internal consistency of the scale items) for this new scale (and in the current study) was 0.89.

Sense of Coherence

This 13 item scale focuses on meaningfulness (4 items), comprehensibility (5 items), and manageability (4 items) using a 7 point Likert-type scale with anchors 1 (very often) and 7 (very seldom; never). Total scores range from 13 to 91. Higher scores indicate a stronger SOC. The test-retest correlations demonstrated stability (Antonovsky, 1987, 1993; Konttinen, Haukkala & Uutela, 2008). While Cronbach’s alpha have ranged from 0.74 to 0.91, Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was 0.60.

Self Compassion Scale

This twelve item instrument, adapted from Neff’s (2003) 26 item Self-Compassion scale, queries participants regarding their response to difficult situations using a five point Likert-type scale with response options of 1 = almost never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = frequently, and 5 = almost always with scores ranging from 26–130. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability for the original 26 item instrument was 0.92 and current Cronbach’s alpha reliability is 0.72.

Engagement with the Provider

The thirteen scale items evaluate the relationship of the research participant with their HCP (Bakken, et al., 2000). Item responses range from 1 = always true to 4 = never with scores ranging from 13–52. An initial question asks the participant who their HCP is by professional discipline i.e. doctor, nurse, nurse practitioner, physician’s assistant. Cronbach’s alpha for the current study was 0.96.

Adherence

Antiretroviral medication adherence was assessed by two one item measures; namely, the 3 and 30 day self-report visual analog scales based on Walsh and colleagues’ 30 day adherence assessment (Walsh, Mandalia & Gazzard, 2002). Participants indicate on a scale from 0% to 100% “For the past 3 days (30 days), what percent of the time were you able to take your medications exactly as prescribed?” The construct validity of the 3 day visual analog scale was supported in a study by Rivet and colleagues (2006).

Data analysis

Statistical tests included (a) descriptive statistics, (b) multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) in which several independent variables and dependent variables are examined for the significance of group differences, analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis in which several independent variables are related to one dependent variable to examine the significance of differences, and (c) path analysis which examined the magnitude and significance of the hypothesized relationships (Myers, Gamst, & Guarino, 2006). All tests were conducted using SPSS 19 and Amos19 statistical packages.

Results

The sample (N=2082) was composed primarily of men (68.3%; n=1404) and was largely African American/black (41.2%, n=849) white (21.4%, n=441) or Hispanic (20.2%, n = 415). The mean age for the sample was 44.9 years (SD=9.4). The sample was relatively equally divided by education although only 25% (n=515) worked for pay. Statistically significant differences by site included age, work for pay and whether participants were informed of their AIDS status.

The mean number of SLEs for the total sample was 5.69 (SD=4.88) and 89% of the sample had at least one SLE. Other statistically significant differences (p= <.01) included; the Canadian site having the highest average number of SLEs (M=7.28), lowest SOC (M=53.1), and the lowest adherence whether for the past 3 days (M=86.49) or past 30 days (M=84.12); the Chinese site with the least eHCP (M=24.75) and lowest average number of SLEs (M=2.6); and the Namibian site exhibiting the highest SOC (M=60.99), the most SCS (M=38.23), lowest eHCP (M=14.92) (lower values indicate higher levels of eHCP, and adherence whether of 3 days (M=96.21) or 30 days (M=95.81).

A one-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed on six dependent variables: (a) SLEs, (b) SOC, (c) SCS, (d) eHCP, and (e) antiretroviral adherence past 3 days and past 30 days. The independent variable was international site at five levels, (a) U.S., (b) Canada, (c) Puerto Rico, (d) Namibia, and (e) China was employed to determine whether the sites differed with respect to the dependent variables. The results of the MANOVA indicated a significant effect, F(28,5932) = 10.91, p < .001, partial η2 = .044 warranting further investigation as to the relationships of the independent variables by site.

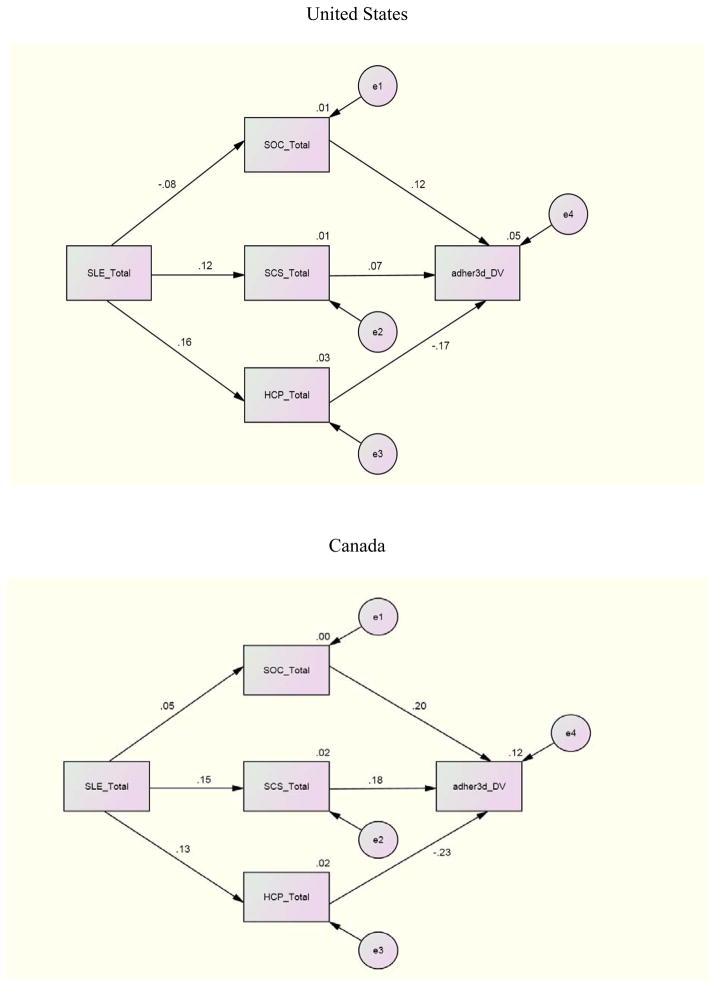

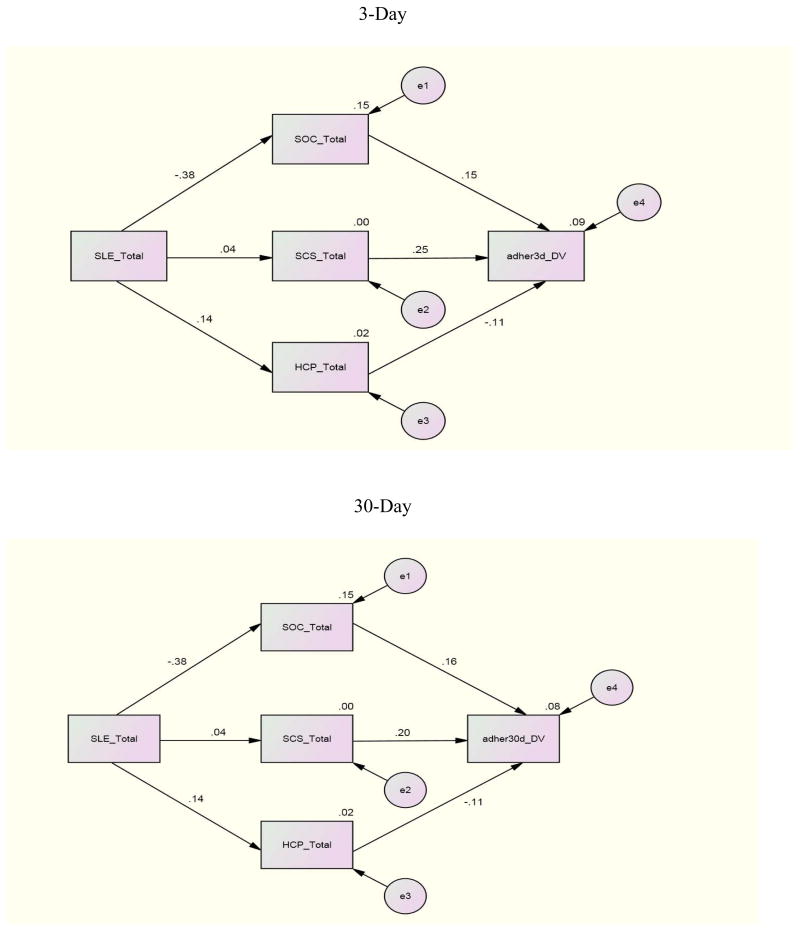

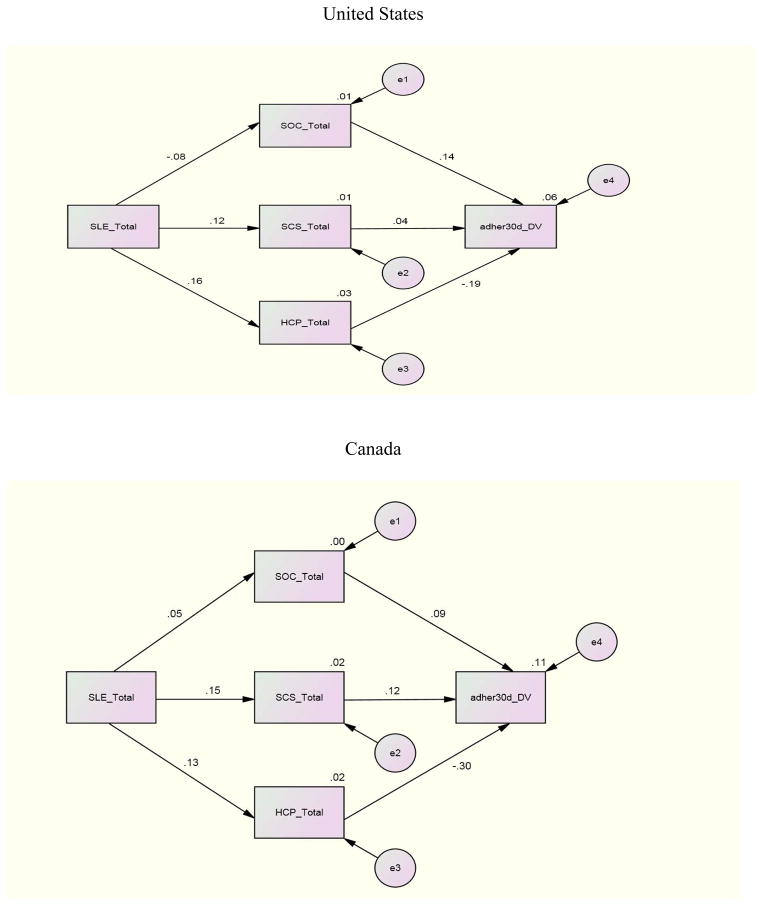

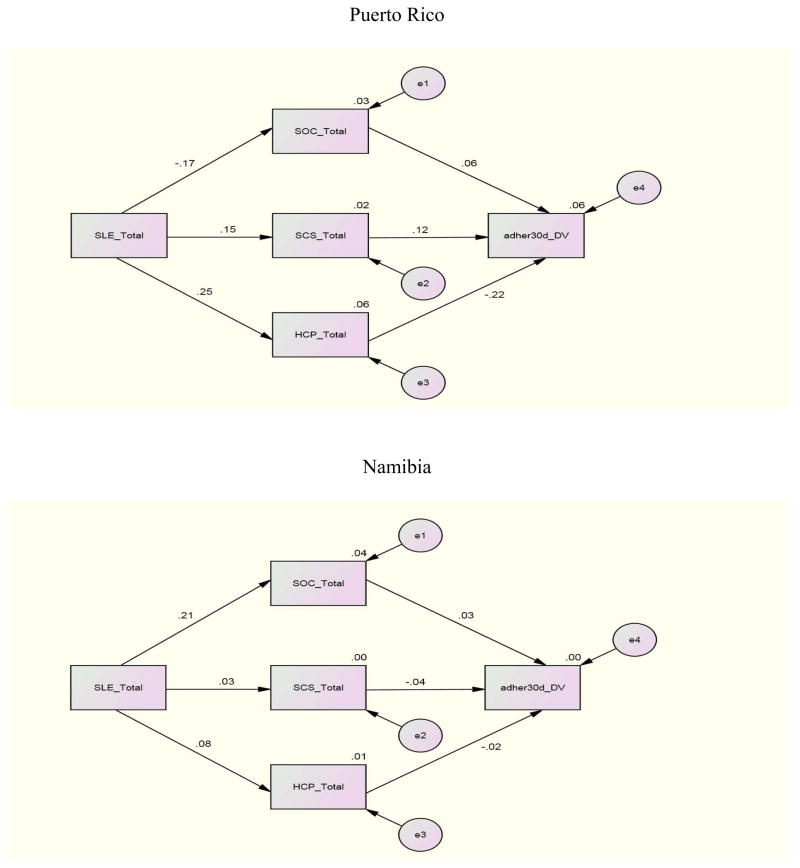

For the structural equation where adherence (past 3 day) was regressed on SOC, SCS, and eHCP to investigate the individual relationships between these variables, Canada demonstrated significant paths between SOC (β = .20), eHCP (β = −.23) and adherence (past 3 day). Namibia and Puerto Rico demonstrated a significant path only between eHCP (β = −.26; β = −.34) and adherence (3 day). No other international site demonstrated significant paths for the first structural equation. Other relationships between variables included a significant path between SLE and SOC with β =.21 and β = −.38 for Namibia and China and a significant path (β =.25) between SLE and eHCP for Puerto Rico. There were no significant structural paths between these variables for the U.S. and the data were not available for Thailand.

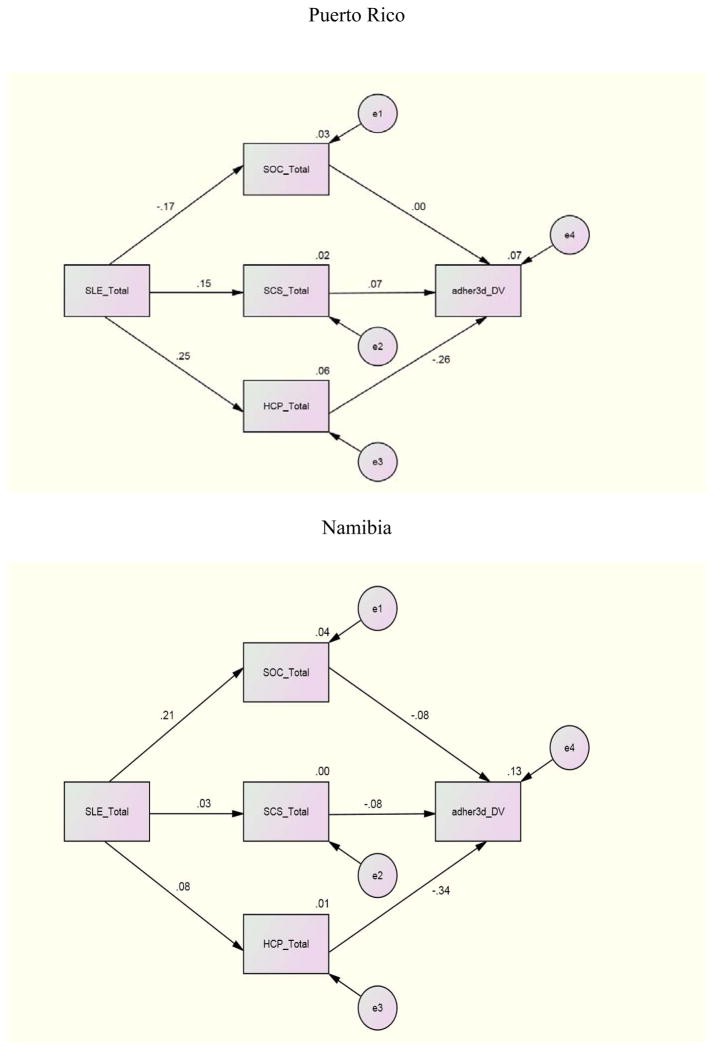

For the relationships for adherence (30 day) with the independent variables for each individual site, Canada and Puerto Rico demonstrated significant paths between eHCP and adherence (30 day) with paths of β = −.30 and β = −.22 respectively. China demonstrated a significant path (β =.20) between SCS and adherence (30 day); China and Namibia reported significant paths between SLE and SOC with coefficients of β = −.38 and β =.21 respectively

To investigate the combined impact of the independent variables on adherence by international site, an examination of the relationships between SLE, SCS, SOC and eHCP with adherence (3 day, 30 day) by international site indicated these combined variables were related to adherence whether 3 day or 30 day to different degrees at the various sites. The combination of SLE, SCS, SOC, and eHCP was a significant predictor of adherence past 3 days for the U.S (p= <.001), Canada (p= .006), and Namibia (p= .019). The combined independent variables were significant predictors of adherence past 30 days only in the U.S. and Canada.

Further analyses for the international sites where significant results occurred indicated that for the U.S. whether for 3 or 30 day adherence all of the independent variables contributed to an explanation of the variance. For Namibia, 11% of the 12% explained variance was due to the relationship of eHCP with adherence 3 day. In Canada, eHCP contributed almost half (6.7% of 14%) of the explained variance for 30 day adherence but less for 3 day adherence (3.6% of 17%). These finding underscore the importance of eHCP for explaining adherence whether 3 day or 30 day.

Discussion

We found statistically significant (p <.001) socio-demographic differences by international site including age, gender, ethnicity, education, work for pay, and AIDS diagnosis. Whether one works for pay is a reflection of the country’s economic situation, availability of jobs, and individual’s health and support. Similarly, whether one responds they have been informed they have AIDS reflects memory, whether HCPs reveal such information, and the participant’s illness stage. It is interesting that the Thai participants were both more likely to have been diagnosed with AIDS and to be employed. The Chinese sample was just a little more likely than not (56.1%) to work for pay but most hadn’t been informed they have AIDS (86%). Whether these findings reflect differences in study participants or larger cultural differences is not clear.

Antiretroviral adherence is influenced by numerous factors but eHCP is primary with even stronger relationships with 30 day adherence. Simoni, Kurth, Pearson, Pantalone, O’Merrill, and Frick (2004) suggest that longer recall periods are more likely to be correlated with viral load. The exceptions to the strength of the longer recall period are Puerto Rico and Namibia where declines in the relationship were experienced. Given that Namibia does not educate its own physicians and pharmacists and is experiencing rapid nurse turnover, the opportunity for long-term HCP relationships may be affected (UNGASS, 2010). The lack of a full-time senior professional nurse or doctor was a significant risk factor for retention on ARVs in South Africa (Vella, et al., 2010). These results emphasize the importance of both HCP availability and quality of the patient-provider relationship (Aragones, Sanchez, Campos, & Perez, 2011; Kagee, 2008).

Our Canadian data underscore the importance of addressing adherence as a public health challenge that requires intersectoral collaboration to optimize the outcomes of large-scale ARV therapy interventions such as those in British Columbia and being planned in China (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, 2011; Lima, Hogg, & Montaner, 2010; Montaner, et al., 2010). Financial difficulties in paying for care reflect both site differences in availability of free care and individual differences in affording required care. Boyer and colleagues (2011) identified financial difficulties as significant for treatment interruption.

The variables investigated in this study were of varying salience for the international sites. Much of the variance for antiretroviral adherence remained unexplained attesting to the multi-natured aspect to achieving adherence. That none of the independent variables contributed to the explained variance for Canada which had the highest overall explained variance (17%), reflects issues of shared variance and the complexity of ARV adherence. Further, the environmental/contextual factors (SLE), regulatory factors, (SOC, SCS, eHCP) with outcome (ARV adherence) varied among the study’s international sites. The significance of eHCP for adherence was highlighted as it was by Watt and colleagues (2010) who emphasized the importance of the quality of that interaction.

This study’s limitations include: the unequal representation of participants with most of the sample from the United States; self-selected participation; cross-sectional design precluding investigation of changes over time; and the question of the transferability of concepts to different international sites as potentially illustrated by the of 0.60 Cronbach’s alpha reliability for SOC, lower than that found in other studies (Eriksson & Lindstrom, 2006). In addition, the self-reported adherence measure may be subject both to recall bias and social desirability bias and may have resulted in overestimates of adherence (Grossberg, Zhang & Gross, 2004). Nevertheless, self-report is noted to be the least burdensome and least costly measure (Simoni, Kurth, Pearson, Pantalone, O’Merrill, & Frick, 2004).

We have accommodated for unequal sample size by comparing within country differences. Nevertheless, the disadvantage of too large a sample is that analyses may result in statistical significance but not practical significance and limited power to detect differences between those sites with a small sample compared with composite U. S. sites. Differences in the criteria used for prescription of antiretroviral therapy (CD4<350/mm3 for all sites other than Thailand (CD4 count of <200/mm3) likely did not affect the results given the Thai site did not collect data on all of the study instruments and thus was not included in many analyses.

Given the significance of eHCP for ARV adherence, further investigation as to factors that enhance or impede the development of positive relationships, including the impact of relationship continuity, would be helpful. In addition, identifying variables with greater salience in different countries will help researchers isolate factors key to understanding outcomes of concern such as the different types of adherence i.e. antiretroviral, appointment, or condom use.

Conclusions

The relationship between SLEs and adherence is mediated through complex associations among cultural context (site) and degree of SCS, SOC, and eHCP. And while these complex relationships differ by international site, eHCP consistently demonstrated statistical significance for ARV adherence in most of these countries. Another study contribution is to underscore that similarity of relationships for variables of interest cannot be assumed for different countries.

The importance of regular and positive eHCP cannot be overstated. Of all of this study’s independent variables, eHCP made the largest contribution to both 3 and 30 day adherence. As Remien, Stiratt, Dognin, Day, El-Bassel, and Warne (2006) note, social support makes an important contribution to adherence. The items in the eHCP scale query the degree to which the provider listens to the patient, spends enough time with the patient, and incorporates the patient in decision-making, as well as other indicators of caring and attention. This suggests it is not so much what the HCP says but the degree to which the patient feels he or she is heard. The challenge is to make such engagement as high a priority as checking viral load, CD4 count, and the number of pills remaining in the bottle, if the patient is to remain adherent.

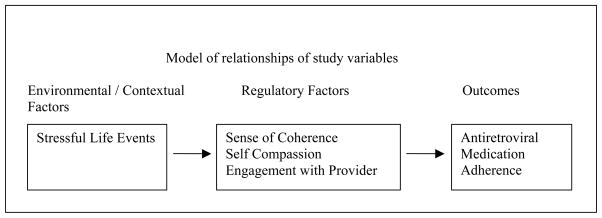

Figure 1.

Social Action Theory

Figure 2.

Path Analysis Model of 3-Day ARV Adherence – United States, Canada

Figure 3.

Path Analysis Model of 3-Dau ARV Adherence – Puerto Rico, Namibia

Figure 4.

Path Analysis Model of 3-Day and 30-Day ARV Adherence - China

Figure 5.

Path Analysis Model of 30-Day ARV Adherence – United States, Canada

Figure 6.

Path Analysis Model of 30-Day ARV Adherence – Puerto Rico, Namibia

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample by International Site by International Site

| Variable | Total | U.S. | Canada | P.R. | Namibia | China | Thailand | Cramer’s V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age M, (SD) | 44.9 (9.4) | 45.9 (9.2) | 47.1(8.2) | 45.0(8.7) | 39.3(9.1) | 37.6(9.7) | 39.7(7.9) | .233* |

|

| ||||||||

| Gender | 2057 | 1557 | 93 | 98 | 102 | 107 | 100 | .162* |

|

| ||||||||

| Female | 608 (29.6) | 420 (27) | 14 (15.1) | 54(55.1) | 53(52) | 17(15.9) | 50 (50) | |

| Male | 1404 (68.3) | 1099 (70.6) | 74 (79.6) | 44 (44.9) | 47(46.1) | 90(84.1) | 50 (50) | |

| Transgender | 45 (2.2) | 38 (2.4) | 5 (5.4) | 0 | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | |

| Ethnicity | 2056 | 1547 | 100 | 100 | 102 | 107 | 100 | .504* |

|

| ||||||||

| Asian/P.I. | 233 (11.3) | 22 (1.4) | 4(4) | 0 | 0 | 107(100) | 100 | |

| AA/Black | 849 (41.2) | 749(48.4) | 2(2) | 1(1) | 97 (95.1) | 0 | 0 | |

| Hispan/Latin | 415 (20.2) | 317(20.5) | 2(2) | 96 (96) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| White | 441 21.4 |

389 (25.1) | 51(51) | 1(1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Nat.Amer In | 64 (3.1) | 30(1.9) | 34(34) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 54(2.6) | 40 (2.6) | 7 (7) | 2 (2) | 5(4.9) | 0 | 0 | |

| Education | 2064 | 1557 | 99 | 100 | 102 | 107 | 100 | .145* |

|

| ||||||||

| 11th grade or < | 610 (30) | 397 (25.5) | 47(47.5) | 37(37) | 46(45.1) | 24(22,4) | 59(59) | |

| H.S,/GED | 778 (38) | 645(41.4) | 21(21.2) | 36(36) | 11(10.8) | 40(37.4) | 25(25) | |

| College + | 677 (33) | 515(33.1) | 31(31.3) | 27(27) | 45(44.1) | 43(40.2) | 16(16) | |

| Work for Pay | 2059 | 1562 | 91 | 100 | 102 | 107 | 97 | .353* |

|

| ||||||||

| Yes | 515 (25) | 314(20.1) | 21(23.1) | 9(9) | 32(31.4) | 60(56.1) | 79(81.4) | |

| No | 1544 (75) | 1248(79.9) | 70(76.9) | 91(91) | 70(68.6) | 47(43.9) | 18(18.6) | |

| Told AIDS | 2022 | 1548 | 91 | 98 | 96 | 107 | 82 | .291* |

|

| ||||||||

| Yes | 887(43.9) | 664(42.9) | 36(39.6) | 33(33.7) | 75(78.1) | 15(14) | 64(78) | |

| No | 1097(54.3) | 887(56) | 54(59.3) | 63(64.3) | 21(21.9) | 92(86) | 0 | |

| Don’t Know | 38 (1.9) | 17(1.1) | 1(1.1) | 2(2) | 0 | 0 | 18(22) | |

p < .001

Table 2.

Mean differences in Stressful Events, Sense of Coherence, Self-Compassion, Engagement with Health Care Provider Adherence to ARNs (3 day, 30 day) by International Site

| Variable | Country | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. | Canada | P.R. | Namibia | China | Thailand | ||

| Stressful Life Events* (Range 0–20) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| n | 1571 | 98 | 100 | 102 | 106 | n/a | 1977 |

| M | 5.77 | 7.28 | 5.0 | 6.78 | 2.60 | 5.69 | |

| SD | 4.91 | 5.39 | 4.8 | 4.04 | 3.15 | 4.88 | |

| Sense of Coherence* (Range 13–91) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| n | 1573 | 99 | 100 | 102 | 106 | n/a | 1980 |

| M | 55.82 | 53.1 | 57.64 | 60.99 | 55.83 | 56.04 | |

| SD | 10.49 | 10.89 | 12.52 | 12.91 | 10.3 | 10.82 | |

| Self-Compassion* (Range 26–130) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| n | 1573 | 98 | 99 | 102 | 107 | 100 | 2079 |

| M | 34.99 | 33.7 | 36.66 | 38.23 | 33.19 | 30.85 | 34.88 |

| SD | 6.82 | 7.51 | 9.1 | 9.88 | 7.12 | 7.75 | 7.32 |

| Engagement with Health Care Provider* (Range 13–52) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| n | 1562 | 93 | 99 | 102 | 107 | n/a | 1963 |

| M | 17.77 | 19.46 | 15.35 | 14.92 | 24.75** | 17.96 | |

| SD | 7.51 | 8.45 | 5.08 | 3.98 | 9.68 | 7.67 | |

| Adherence to ARVs – past 3 days* (Range 0–100) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| n | 1327 | 87 | 91 | 99 | 88 | 99 | 1791 |

| M | 88 | 86.49 | 89.03 | 96.21 | 91.8 | 91.52 | 88.82 |

| SD | 22.25 | 26.13 | 19.61 | 8.98 | 14.34 | 11.55 | 21.10 |

| Adherence to ARVs – past 30 days* (Range 0–100) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| n | 1323 | 85 | 91 | 99 | 88 | 98 | 1784 |

| M | 85.37 | 84-.12 | 88.66 | 95.81 | 90.82 | 91.63 | 86.67 |

| SD | 22.09 | 24.67 | 20.06 | 12.03 | 14.40 | 10.12 | 21.05 |

Indicates that there were statistically significant differences among the sites with p < .01.

Higher means indicate less engagement with the provider.

Table 3.

ARV adherence past 3 days, and past 30 days related to Stressful Life Events (SLE), Self Compassion (SCS), Sense of Coherence (SOC) and Engagement with Health Care Provider (eHCP) for U.S., Canada, Puerto Rico, Namibia and China

| Country | Adherence past 3 days | R | R2 | d/f | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. | .241 | .06 | 4.3 | 20.24 | <.001* | |

| Canada | .408 | .06 | 4.79 | 3.96 | .006* | |

| Puerto Rico | .279 | .08 | 4.84 | 1.77 | .143 | |

| Namibia | .341 | .12 | 4.94 | 3.10 | .019 | |

| China | .304 | .09 | 4.82 | 2.08 | .090 | |

| Adherence past 30 days | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| U.S. | .284 | .08 | 4.13 | 28.82 | <.001* | |

| Canada | .375 | .14 | 4.77 | 3.15 | .019* | |

| Puerto Rico | .258 | .07 | 4.84 | 1.49 | .211 | |

| Namibia | .141 | .02 | 4.94 | .47 | .755 | |

| China | .273 | .07 | 4.82 | 1.65 | .170 | |

Table 4.

B-weights, Beta, Part-correlation squared (s2), significance level for 3 day ARV adherence U.S. Canada and Namibia; 30 day ARV adherence U.S. and Canada

| US 3 day adherence R 2 = 6% | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Model | Un-standardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Correlations | ||

|

|

|

||||||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | s2 | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 75.813 | 4.675 | 16.215 | .000 | ||

| SLE Total | −.528 | .124 | −.117 | −4.263 | .000 | .013 | |

| SCS Total | .273 | .088 | .084 | 3.117 | .002 | .006 | |

| SOC Total | .234 | .058 | .109 | 4.059 | .000 | .012 | |

| HCP Total | −.423 | .082 | −.140 | −5.148 | .000 | .019 | |

| Canada 3 day adherence R 2= 17% | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Model | Un-standardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Correlations | ||

|

|

|

||||||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | s2 | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 55.828 | 20.498 | 2.724 | .008 | ||

| SLE Total | −.643 | .537 | −.126 | −1.198 | .235 | .015 | |

| SCS Total | .654 | .377 | .181 | 1.735 | .087 | .032 | |

| SOC Total | .484 | .273 | .200 | 1.768 | .081 | .033 | |

| HCP Total | −.661 | .355 | −.211 | −1.862 | .066 | .036 | |

| Namibia 3 day adherence R 2 = 12% | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Model | Un-standardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Correlations | ||

|

|

|

||||||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | s2 | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 113.859 | 6.290 | 18.102 | .000 | ||

| SLE Total | .014 | .221 | .006 | .065 | .948 | < .001 | |

| SCS Total | −.070 | .090 | −.079 | −.784 | .435 | .006 | |

| SOC Total | −.057 | .071 | −.082 | −.793 | .430 | .006 | |

| HCP Total | −.785 | .231 | −.334 | −3.404 | .001 | .110 | |

| US 30 day adherence R 2 = 8% | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Model | Un-standardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Correlations | ||

|

|

|

||||||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | s2 | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 75.678 | 4.566 | 16.576 | .000 | ||

| SLE_Total | −.756 | .121 | −.169 | −6.237 | .000 | .027 | |

| SCS_Total | .199 | .087 | .061 | 2.297 | .022 | .004 | |

| SOC_Total | .269 | .056 | .127 | 4.796 | .000 | .016 | |

| HCP_Total | −.458 | .082 | −.150 | −5.567 | .000 | .022 | |

| Canada 30 day adherence R 2 = 14% | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Model | Non-standardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Correlations | ||

|

|

|

||||||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | s2 | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 77.575 | 19.790 | 3.920 | .000 | ||

| SLE_Total | −.478 | .519 | −.100 | −.920 | .360 | .009 | |

| SCS_Total | .440 | .363 | .130 | 1.212 | .229 | .016 | |

| SOC_Total | .206 | .263 | .092 | .785 | .435 | .007 | |

| HCP_Total | −.852 | .348 | −.286 | −2.445 | .017 | .067 | |

Dependent Variable: adher3d_DV for past 3 days, what percent of time were you able to take meds

Dependent Variable: adher3d_DV for past 3 days, what percent of time were you able to take meds

Dependent Variable: adher3d_DV for past 3 days, what percent of time were you able to take meds

Dependent Variable: adher30d_DV for past 30 days, what percent of time were you able to take meds

Dependent Variable: adher30d_DV for past 30 days, what percent of time were you able to take meds

References

- Alakija Kazeem S, Fadeyl A, Ogunmodede JA, Desalu O. Factors influencing adherence to antiretroviral medication in Ilorin, Nigeria. Journal of the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care. 2010;9(3):191–195. doi: 10.1177/1545109710368722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglemyer A, Rutherford GW, Egger M, Siegfried N. Antiretroviral therapy for prevention of HIV Transmission in HIV-discordant couples. Cochrane Database Systematic Review. 2011;5:CD009153. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Social Science & Medicine. 1993;36(6):725–33. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health. How people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Aragones C, Sachez L, Campos JR, Perez J. Antiretroviral therapy adherence in Persons with HIV/AIDS in Cuba. MEDICC Review. 2011;13(2):17–23. doi: 10.37757/MR2011V13.N2.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakken S, Holzemer WL, Brown MA, Powell-Cope GM, Turner JG, Inouye J, Corless IB. Relationships between perception of engagement with health care provider and demographic characteristics, health status, and adherence to therapeutic regimen in persons with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2000;14(4):189–197. doi: 10.1089/108729100317795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottonari K, Safren S, McQuaid J, Hsiao C-B, Roberts J. A longitudinal investigation of the impact of life stress on HIV treatment adherence. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;33(6):486–495. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9273-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer S, Clerc I, Bonono C, Marcellin F, Bile P, Ventelou B. Non-adherence to antiretroviral treatment and unplanned treatment interruption among people living with HIV/AIDS in Cameroon: Individual and healthcare supply-related factors. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72(8):1383–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS. China implements BC-CFE’s Treatment as Prevention Strategy as the Country’s National HIV/AIDS Policy. BC Centre; 2011. Feb 24, Retrieved from http://www.cfnet.ubc.ca/news/releases/china-implements-bc-cfe's-treatment-prevention-strategy-country's-national-hivaids-pol. [Google Scholar]

- Brugha TS, Bebbington PE, Tennant C, Hurry J. The List of Threatening Experiences: a subset of 12 life event categories with considerable long-term contextual threat. Psychological Medicine. 1985;15(1):189–194. doi: 10.1017/S00329170002150X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N the HPTN 052 Study Team. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011 Jul 18; epub. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Shaw GM, McMichael MB, Haynes BF. Acute HIC-1 infection. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364(20):1943–1954. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1011874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demmer C. Relationship with health care provider and adherence to HIV medications. Psychological Reports. 2003;93(2):494–496. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2003.93.2.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson M, Lindstrom B. Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale and relation with health: a systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2006;60(5):376–381. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.041616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewart CK. Social action theory for a public health psychology. American Psychologist. 1991;46(9):931–946. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.9.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl MA, Richman DD, Grieco MH, Gottlieb MS, Volberding PA, Laskin OL the AZT Collaborative Working Group. The efficacy of azidothymidine (AZT) in the treatment of patients with AIDS and AIDS-related complex. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. New England Journal of Medicine. 1987;317(4):185–191. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198707233170401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossberg R, Zhang Y, Gross R. A time-to-prescription measure of antiretroviral adgerence predicted changes in viral load in HIV. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2004;57:1107–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan M, Griffin MT, McNulty R, Sr, Fitzpatrick JJ. Self-compassion and emotional intelligence in nurses. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2010;16(4):366–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2010.01853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzemer WL. The efficacy of an HIV symptom management manual. Protocol 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MO, Carrico AW, Chesney MA, Morin SF. Internalized heterosexism among HIV-positive, gay-identified men; implications for HIV prevention and care. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(5):829–839. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.5.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MO, Chesny MA, Goldstein RB, Remien RH, Catz S, Gore-Felton C the NIMH healthy living Project team. Positive provider interactions, adherence self-efficacy, and adherence to antiretroviral medications among HIV-infected adults: A mediation model. AIDS Patients Care and STDs. 2006;20(4):115–125. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagee A. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in the context of the national roll-out in South Africa: Defining a research agenda for psychology. South African Journal in Psychology. 2008;38(2):413–428. [Google Scholar]

- Konttinen H, Haukkala A, Uutela A. Comparing sense of coherence, depressive symptoms and anxiety, and their relationships with health in a population-based study. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;66(12):2401–2412. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langius-Eklof A, Lidman K, Wredling R. Health-related quality of life in relation to sense of coherence in a Swedish group of HIV-infected patients over a two-year-follow-up. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2009;23(1):59–64. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J, Ironson G, O’Cleirigh C, Fordiani JM, Balbin E. Stressful life events and adherence in HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2008;22(5):403–411. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima VD, Hogg RS, Montaner JSG. Expanding HAART treatment to all currently eligible individuals under the 2008 IAS-USA guidelines in British Columbia, Canada. PLOS ONE. 2010;5(6):e10991. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaner J. Treatment as prevention–a double hat-trick. Lancet. 2011;378(9787):208–209. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60821-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaner JS, Wood E, Kerr T, Lima V, Barrios R, Shannon K, Hogg R. Expanded highly active antiretroviral therapy coverage among HIV-positive drug users to improve individual and public health outcomes. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2010;55(Supplement 1):S5–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f9c1f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers L, Gamst G, Guarino AJ. Applied multivariate research Design and Interpretation. Newbury Park, CA: Sage publishing Co; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity. 2003;2:223–250. [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD, Rude S, Kirkpatrick KL. An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41:908–916. [Google Scholar]

- Pham PN, Vinck P, Kinkodi DK, Weinstein HM. Sense of coherence and association with exposure to traumatic events, post-traumatic stress disorder, and depression in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23:313–321. doi: 10.1002/jts.20527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remien RH, Stiratt MJ, Dignin J, Day E, El-Bassel N, Warne P. Moving from theory to research to practice. Implementingan effective dyadic intervention to improve antiretroviral adherence for clinic patients. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2006;43(S1, Suppl):69–78. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248340.20685.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivet AK, Fisher WA, Cornman DH, Shuper PA, Redding CG, Konkle-Parker DJ, Fisher JD. Visual Analog scale of ART adherence: Association with 3-day self-report and adherence barriers. Journal of Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;42(4):455–459. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000225020.73760.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M, Voils CI, Chang Y, Lee EJ. A systematic review comparing antiretroviral adherence descriptive and intervention studies conducted in the USA. AIDS Care. 2009;21(8):953–966. doi: 10.1080/09540120802626212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayles JN, Wong MD, Kinsler JJ, Martins D, Cunningham WE. The association of stigma with self-reported access to medical care and antiretroviral adherence in persons living with HIV/AIDS. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24:1101–1108. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1068-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J, Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Li W, Wilson IB. Better physician-patient relationships are associated with higher reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19:1096–1103. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30418.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Kurth AE, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, O’Merrill JO, Frick PA. Self –report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: A review with recommendations for HIV research and clinical management. AIDS Behavior. 2004;10:227–245. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9078-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosevski DL, Milovancevic MP. Stressful life events and physical health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2006;19(2):184–189. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000214346.44625.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traube DE, Holloway IW, Smith L. Theory development for HIV behavioral health: empirical validation of behavior health models specific to HIV risk. AIDS Care. 23(6):663–670. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.532532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNGASS (United Nations General Assembly Special Session) UNGASS Country Report. Republic of Namibia Ministry of Health and Social Services Reporting Period 2008–2009. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/monitoringcountryprogress/progressreports/2010countries/namibia_2010_country_progress_report_en.pdf.

- Vaughn C, Wagner G, Miyashiro L, Ryan G, Scott JD. The role of home environment and routinization in ART adherence. Journal of the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care. 2011;10(3):176–182. doi: 10.1177/1545109711399365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vella V, Govender T, Diamini S, Taylor M, Moodley I, David V, Jinabhai C. Retrospective study on the critical factors for retaining patients on antiretroviral therapy in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes: JAIDS. 2010;55(1):109–115. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e7744e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volberding PA. AIDS Overview. In: Corless Inge B, Pittman-Lindeman Mary., editors. AIDS: Principles, Practices, and Politics. New York: Hemisphere Publishing Corporation; 1989. pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh JC, Mandalia S, Gazzard BG. Responses to a 1 month self-report on adherence to antiretroviral therapy are consistent with electronic data and virological treatment outcomes. AIDS. 2002;16:269–277. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200201250-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Zhou J, He G, Luo Y, Li X, Yang A, Fennie K, Williams AB. Consistent ART adherence is associated with improved quality of life, CD4 counts, and reduced hospital costs in central China. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2009;25(8):757–763. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wantland DJ, Holzemer WL, Moezzi S, Willard SS, Arudo J, Kirksey KM, Huang E. A randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy of an HIV/AIDS symptom management manual. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2008;36(3):235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt MH, Maman S, Golin CE, Earp JA, Eng E, Bangdiwala SI, Jacobson M. Factors associated with self-reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a Tanzanian setting. AIDS Care. 2010;22(3):381–389. doi: 10.1080/09540120903193708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webel A, Phillips JC, Dawson Rose C, Holzemer WL, Chen W-T, Tyer-Viola L, Salata RA. A cross-sectional description of social capital in an international sample of persons living with HIV/AIDS (PLWH) BMC Public Health. 2012;12:188. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]