Abstract

Open reading frame (ORF) phage display is a new branch of phage display aimed at improving its efficiency to identify cellular proteins with specific binding or functional activities. Despite the success of phage display with antibody libraries and random peptide libraries, phage display with cDNA libraries of cellular proteins identifies a high percentage of non-ORF clones encoding unnatural short peptides with minimal biological implications. This is mainly because of the uncontrollable reading frames of cellular proteins in conventional cDNA libraries. ORF phage display solves this problem by eliminating non-ORF clones to generate ORF cDNA libraries. Here I summarize the procedures of ORF phage display, discuss the factors influencing its efficiency, present examples of its versatile applications, and highlight evidence of its capability of identifying biologically relevant cellular proteins. ORF phage display coupled with different selection strategies is capable of delineating diverse functions of cellular proteins with unique advantages.

Keywords: Open reading frame phage display, ORF phage display, Protein-protein interaction, Phagocytosis ligand, Functional proteomics

1. Introduction

1.1. Phage display with different libraries

Phage display is a technology to express foreign proteins or peptides as phage capsid fusion proteins so that the surfaced-displayed proteins can be physically linked to their cDNA inserts inside the same phage particles. Multi-round phage selection and amplification efficiently enrich clones displaying proteins with specific binding or functional activities [1–3]. The proteins displayed on enriched phages are conveniently identified by sequencing their cDNA inserts.

Since its first description in 1985 [4], phage display has been widely used to identify antibodies or short peptides with specific binding activities from antibody libraries or random peptide libraries [3,5]. These identified antibodies and peptides have been demonstrated for their valuable applications in basic research, clinical diagnosis and disease therapy [6]. It was expected that this powerful technology would also revolutionize our capability to identify cellular proteins with specific functional activities. Surprisingly, conventional phage display has not been used to systematically delineate cellular protein functions as have other technologies of functional proteomics, e.g., yeast two-hybrid systems and mass spectrometry. Overall, only ~5% of more than 5,000 phage display-related papers in the PubMed database deal with cDNA libraries [7]. The majority of the published studies focus on antibody libraries or random peptide libraries. The question is then why phage display has been underexploited for delineating cellular protein functions.

The answer lies mainly in the lingering problem of how to genetically fuse cellular library proteins to a phage capsid in the correct reading frames for appropriate expression and display of the fusion proteins on the phage surface. Given that antibodies with different amino acid residues in antibody variable regions have predictable reading frames, it is relatively convenient to generate phage display antibody cDNA libraries without reading frame problems [8]. Random peptide libraries have minimal concern on protein reading frames. However, cellular library proteins with unpredictable reading frames will interfere with the expression and display of their capsid fusion proteins. A high percentage of enriched phage clones (~90–94%) from conventional cDNA libraries are non-open reading frames (non-ORFs), encoding unnatural short peptides with minimal biological implication [9,10]. Consequently, phage display has not been used as a technology of functional proteomics to map cellular protein functions.

1.2. The principle of ORF phage display

A typical cDNA sequence of cellular proteins consists of a 5′-untranslated region (UTR), a start codon, a coding region, a stop codon and a 3′-UTR. All coding sequences have six reading frames in two orientations. When full-length cDNA sequences generated by oligoT priming methods are fused to the N-terminus of a phage capsid protein, such as gene III capsid protein (pIII) in filamentous phages, the stop codon and 3′-UTR may interfere with the expression of the C-terminal capsid. Uncontrollable protein reading frames of cDNA sequences further complicate the construction of fusion protein libraries. cDNA sequences generated by random priming methods may minimize the interference of the stop codon and UTRs but have the same problem of uncontrollable reading frames. Non-ORF sequences, including UTRs and coding sequences in incorrect reading frames, have high frequency of stop codons that will prevent the appropriate expression of fusion proteins.

Several strategies have been developed to address the reading frame problems. These include pJuFo phagemid [11] and other phage vectors [12,13] for C-terminal display of library proteins to minimize the interference of non-ORFs with the capsid expression. However, C-terminal display cannot solve the problem of incorrect reading frames for cDNA library proteins themselves.

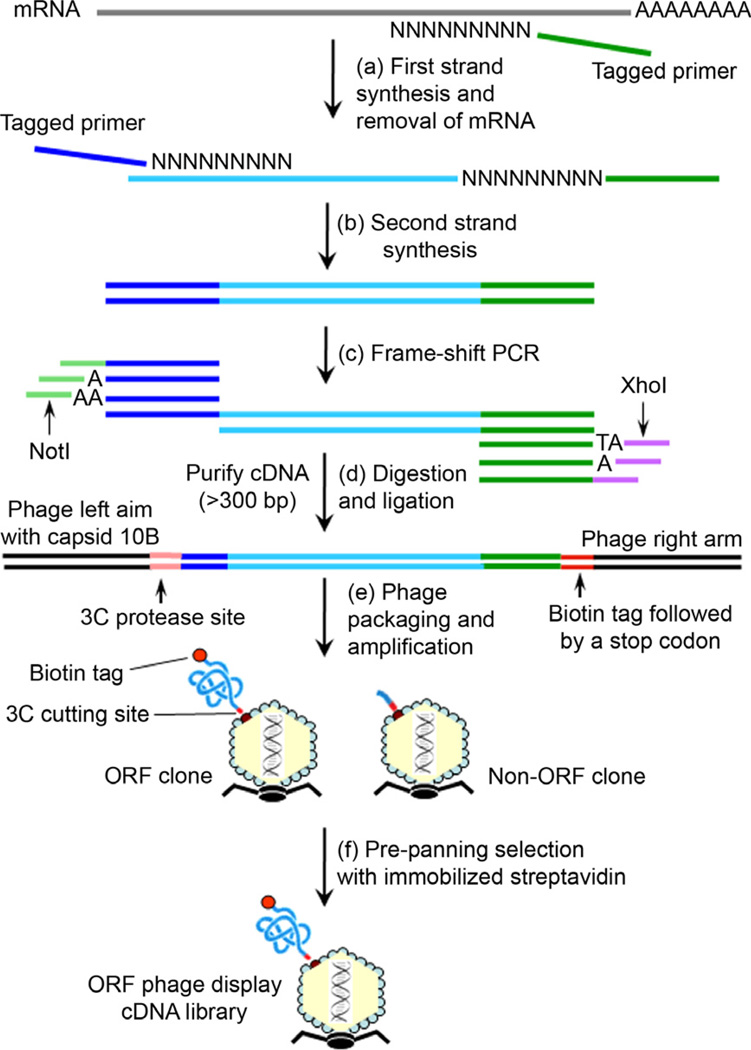

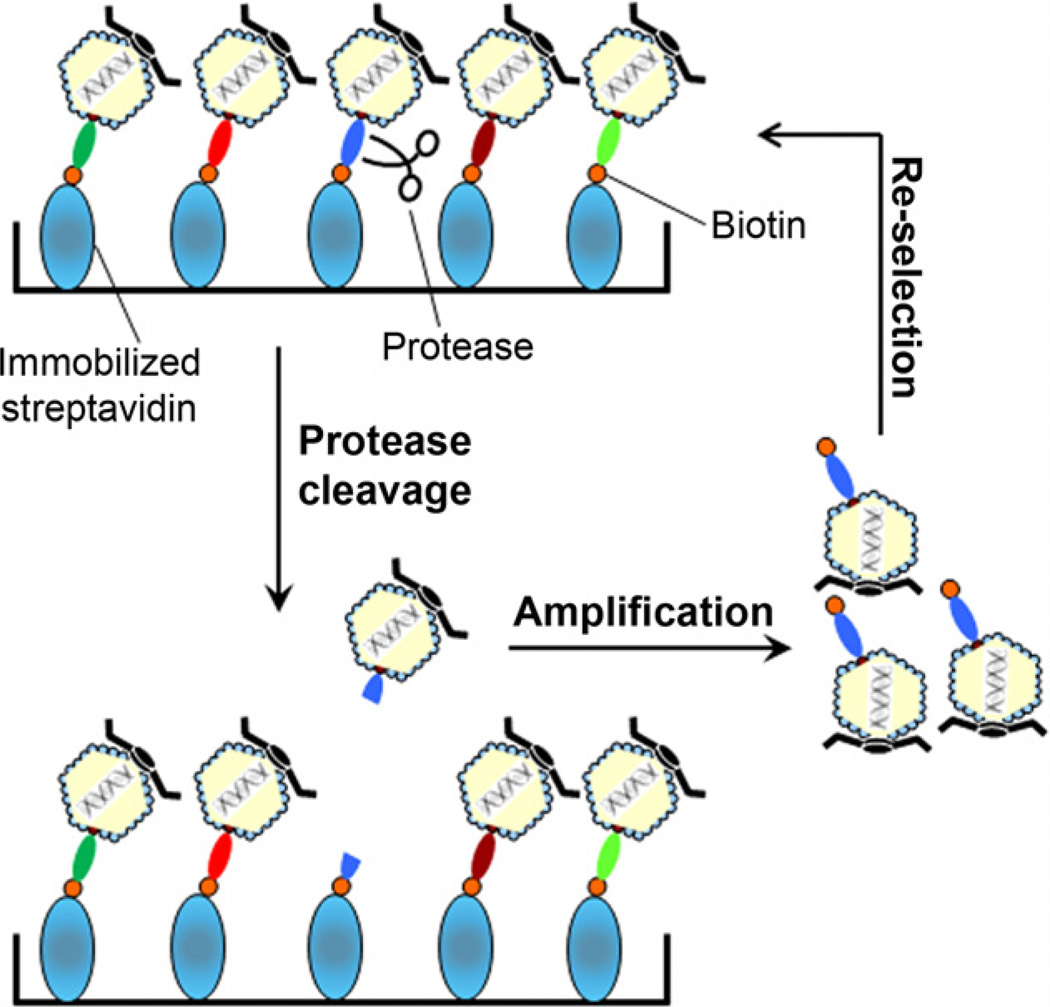

An alternative strategy to tackle the problem is ORF phage display [7]. The principle of this strategy is that ~96% of 200-bp non-ORF cDNAs have at least one stop codon [14]. This number is drastically increased to 99.6% for non-ORF cDNAs with 300 bp. A C-terminal selection marker expressed only with ORF cDNA inserts without a stop codon can be used to generate ORF libraries by eliminating non-ORFs (Fig. 1). For example, a C-terminal biotin tag is expressed and spontaneously biotinylated by the BirA enzyme of Escherichia coli for the selection of ORF clones with immobilized streptavidin [15,16]. Alternatively, a C-terminal β-lactamase gene can be used as a marker for ampicillin selection to eliminate non-ORF clones [17,18]. Other C-terminal selection strategies for ORF phage display were summarized in our earlier review [7].

Fig. 1.

The procedure to construct ORF phage display cDNA library [20,21]. (a) The first strand cDNAs are synthesized from purified mRNA using a random primer with a tagged sequence. (b) After the removal of mRNA by RNase H, the second strand cDNAs are generated with a random primer tagged with a different sequence. (c) The double-stranded cDNAs are used as templates for frame-shift PCR. (d) The orientation-directed PCR products are digested with NotI and XhoI, and ligated into T7Bio3C vector, which has been engineered with a 3C protease cleavage site and C-terminal biotinylation tag as indicated. (e) The ligated DNAs are packaged into T7 phage. The initial phage titer is quantified by plaque assay before phage amplification. (f) The library phages are amplified in bacteria BLT5615 and selected with immobilized streptavidin. ORF phage clones expressing the C-terminal biotin tag are enriched to generate ORF phage display cDNA library.

1.3. Phage vector for ORF phage display

Several phage vectors have been developed for protein display, including M13, fl, fd, T7 and lambda bacteriophages. They can be classified into two major categories: non-lytic (M13, fl and fd) and lytic (T7 and lambda) phages [1,8,12,16]. M13 is the most commonly used vector for antibody and random peptide display. Filamentous phage vectors have been engineered as phagemids so that they can be conveniently manipulated like circular plasmids, including phagemid amplification and library construction. The drawback of these filamentous phage vectors is that foreign proteins displayed on filamentous phages have to be secreted into the periplasma through E. coli membrane with possible sequence bias [1,2,19]. In contrast, lytic phage vectors are linear DNA of large sizes. It is technically more challenging to construct cDNA libraries with lytic phage vectors. However, lytic phages do not require the displayed proteins to be secreted through E. coli membrane and are particularly suitable for unbiased display of mammalian proteins [12,19]. Thus, we prefer lytic phages, such as T7 phage, with unbiased C-terminal protein display for ORF phage display.

2. Description of methods

2.1. Construction of ORF phage display cDNA library

A method of constructing ORF phage display cDNA libraries was described in detail in our recent publications [20,21]. The general procedures and special technical considerations are summarized here (Fig. 1). To minimize the interference of 5′- and 3′-UTRs and to improve the translation of coding sequences as a phage capsid fusion protein, a random priming method is preferred over the oligoT priming method for the synthesis of double-stranded cDNAs. To ensure a correct orientation of the cDNA inserts, the first strand cDNAs are synthesized using a random primer tagged with a unique primer sequence, and the second strand cDNAs are generated using a random primer with a different tag sequence. The resulting double-stranded cDNAs are used as templates for frame-shifting PCR with three upstream and three downstream primers in different frames. NotI and XhoI restriction sites with rare frequencies in mammalian genomes are imbedded in the upstream and downstream primers, respectively. The PCR products are resolved on agarose gel or by other fractionation methods to purify cDNA fragments of 300–1,500 bp, digested with NotI and XhoI, and ligated into an engineered T7Bio3C T7 phage vector at the same cutting sites [20,21]. The ligated DNAs are packaged into phages using T7 package extract (EMD Bioscience). The packaged phages are then quantified by plaque assay to determine the initial phage titer, amplified in BLT5615 bacteria and selected with immobilized streptavidin by eliminating non-ORFs to generate an ORF phage display cDNA library.

The ratios of the primers to the template for the first and second strand cDNA synthesis are critical to generate the double-stranded cDNA fragments in appropriate sizes. If the ratios are too high, the resulting cDNA fragments are relatively short. If the ratios are too low, the resulting cDNAs are too long for some small proteins with short ORFs and natural stop codons. Perhaps an ideal solution to this dichotomy is to generate short and long double-stranded cDNAs (all >300 bp) separately by different primer:template ratios. The resulting ORF libraries would then be characterized for library quality as described below and then pooled together to accommodate both small and large library proteins.

An important improvement for ORF phage display is the integration of the cleavage site for human rhinovirus 3C protease between capsid protein and library protein in T7Bio3C vector (Fig. 1) [20]. The 3C protease specifically cleaves and releases phages bound to bait molecules through the displayed library proteins at 4 °C. In contrast, the conventional elution methods use low pH, SDS (sodium dodecyl sulfate) or less specific trypsin digestion [8]. Phages bound to bait molecules through other phage surface proteins may also be eluted by these non-specific elution methods. 3C protease with high substrate specificity [22] should minimally cleave bait proteins to release non-specifically bound phages. In addition, 3C protease cleavage at 4 °C should have less reversible dissociation of bound phages than trypsin digestion at 37 °C.

A recent study described an ORF peptide library [23], which was generated from ~413,000 synthetic oligos to cover most of the ORF sequences in the human genome. Each oligo encoded 36 amino acids, including an overlap with 7 residues, and is optimized for protein codons and restriction enzyme sites. Additional primers at both ends enabled PCR amplification for library construction. The advantage of this approach is that the library representation is independent of mRNA transcript levels in specific tissues. The limitation is that the relative short peptides may lack necessary conformational epitopes or binding domains for many protein–protein interactions.

2.2. Characterization of ORF cDNA library

The quality of ORF cDNA libraries is the key for efficient identification of cellular proteins with minimal reading frame problems and is defined by three parameters: the initial phage titer, size distribution of cDNA inserts and percentage of ORF phage clones. The initial phage titer before phage amplification represents the library complexity, which is important for covering ~23,000 genes in the human genome. Because of UTRs and frame-shifting PCR, we estimate that an ORF library with an initial titer of 1 × 108 plaque forming unit (pfu) covers each ORF in the human genome in correct reading frames about ~160 times on average.

Given that shorter cDNA inserts have higher ligation efficiency, it is important to characterize the size distribution of cDNA inserts in ORF libraries to ensure the library quality. A higher percentage of small cDNA inserts (<300 bp) may increase the probability of non-ORF clones without a stop codon. The size distribution can be characterized by randomly picking library clones and analyzing their cDNA insert sizes by PCR using flanking primers [20]. The percentage of ORF phage clones can be verified by immunoblot analysis to detect the expression of C-terminal biotin tag using horse-radish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin [20]. Alternatively, the cDNA inserts of randomly-picked phage clones can be amplified by PCR and directly sequenced to characterize both the cDNA insert sizes and percentage of ORF phage clones.

2.3. Pre- and post-panning selection to eliminate non-ORF clones

ORF cDNA libraries can be generated before multi-round phage selection, e.g., panning or biopanning in multi-well plates, by tag-based affinity selection to eliminate non-ORF clones. Such pre-panning ORF selection minimizes the interference of non-ORF clones and improves the efficiency of ORF phage selection. During multi-round phage selection, however, non-ORF clones displaying unnatural short peptides with high activities may re-emerge but can be conveniently re-eliminated by post-panning ORF selection [24]. Enriched phages after the post-panning selection should have a high percentage of ORF clones that encode real endogenous proteins with specific binding or functional activities. Because β-lactamase interferes with unbiased display of library proteins, the selection marker has to be removed through DNA recombination [17]. In this case, post-panning ORF selection is not possible for β-lactamase-based ORF cDNA libraries.

Our experience indicated that stringent post-panning ORF selection is important to ORF phage display, particularly with antibody bait [24]. If necessary, multi-round post-panning ORF selection may be performed to ensure a high percentage of ORF clones. For pre- and post-panning selection with biotin tag, streptavidin immobilized on ELISA plates can be used for enrichment of ORF clones. In addition, large-scale pre-panning selection of phage libraries can also be performed with streptavidin immobilized on magnetic beads [21].

3. Application of ORF phage display

3.1. Principle of phage selection

The key to successful phage display, including ORF phage display, is to select or separate phage clones with specific activities from those without activity. Recovered active clones are amplified and used as inputs for the next round of selection. Multi-round selection and amplification enrich phage clones displaying functionally active proteins. The selection strategies can be classified into two major categories: affinity selection and functional selection.

Affinity selection is based on the binding activities of displayed proteins to bait molecules, which can be purified proteins or non-protein molecules. The baits are usually immobilized on ELISA plates or microbeads to facilitate the separation of bound from unbound phages. Functional selection is more complicated than the affinity selection because proteins have different types of biological functions. Functional selection schemes have to be custom designed according to the function of interest. The following are several examples of affinity and functional selection for ORF phage display.

3.2. Protein–protein interactions

Protein–protein interactions are involved in nearly every biological process and are the most important type of protein function to delineate biological interaction networks, disease mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Many technologies have been developed to identify unknown binding proteins, including yeast-two hybrid system and mass spectrometry [25,26]. Compared with these technologies, one of the major advantages of ORF phage display is its multi-round selection and amplification for sensitive enrichment and identification of less abundant binding proteins with high affinity. All other technologies without such protein amplification capability are less sensitive in identifying binding proteins. Compared with conventional phage display, ORF phage display has better efficiency to delineate protein–protein interactions with minimal reading frame problem.

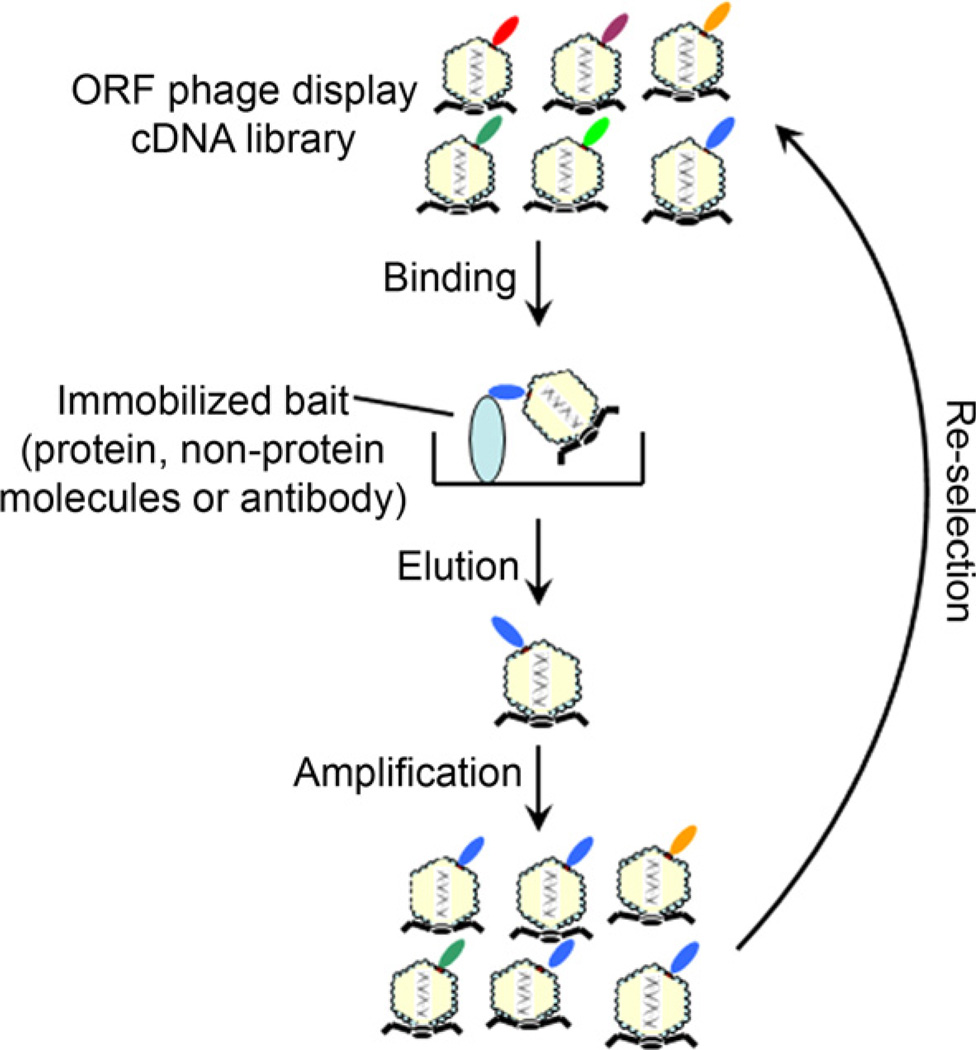

Purified proteins with molecular weight higher than 10–20 kDa can be directly coated on ELISA plates (Fig. 2). Alternatively, purified proteins can be covalently conjugated to microbeads for phage selection. Recombinant proteins with affinity tags can be expressed and purified with affinity columns. These purified proteins, while still binding to their affinity columns, could be directly used for multi-round phage selection, and the bound phages can be eluted along with the purified bait proteins or by 3C protease cleavage. Different affinity tags, such as FLAG tag, HA tag, polyhistidine tag, calmodulin-binding domain, biotin-binding domain, glutathione S-transferase (GST) and maltose-binding protein (MBP), can be used for recombinant protein purification and phage selection. Affinity tag alone without bait protein should be included as a mock control to detect bait-specific enrichment or binding activity.

Fig. 2.

Affinity selection. Purified bait (proteins, non-protein molecules or antibodies) can be immobilized on ELISA plates, blocked and incubated with ORF phage display cDNA libraries. After washing, bound phages are eluted by 3C protease cleavage and quantified by plaque assay. Eluted phages are amplified in bacteria and used as input for the next round of selection. After multi-round selection and amplification, individual phages are randomly picked from the plates of enriched phages and analyzed for their binding activity to the bait or mock control by phage binding assay.

Our group demonstrated that ORF phage display can identify the binding proteins of tubby [20], whose mutation causes adult-onset obesity, retinal and cochlear degeneration by undefined molecular mechanism [27]. We identified 16 new tubby-binding proteins and independently verified 10 out of 14 identified proteins by yeast two-hybrid assay or protein-pulldown assays. The accuracy rate of ORF phage display was estimated to be ~71% [20], suggesting that ORF phage display is a sensitive, efficient and reliable technology to identify unknown binding proteins. Other groups used β-lactamase-based ORF phage display to identify binding proteins for transglutaminase [17,18]. It is worth noting that Di Niro et al. combined next generation DNA sequencing with filamentous ORF phage display to efficiently identify binding proteins for transglutaminase 2 [18].

3.3. Protein interactions with non-protein molecules

Many cellular molecules other than proteins, such as lipids, phospholipids, polysaccharides, DNA and RNA, have been used as non-protein baits for conventional phage display [28–32]. ORF phage display can be applied to all these non-protein baits to efficiently identify their cellular binding proteins with minimal reading frame problem. Phospholipids, such as phosphatidylserine, have been well-characterized for their roles in intracellular and extracellular signaling [33]. RNA binding proteins are of interest because of their regulation of RNA stability, intracellular sorting and translational regulation [30]. DNA binding proteins can regulate transcriptional activity and DNA repair. The key to ORF phage display with non-protein baits is how to immobilize them for efficient phage selection. Biotinylated DNA and RNA can bind to immobilized streptavidin. DNA can also be directly coated as in DNA microarray. Lipids and phospholipids can be dissolved in organic solvents and coated on ELISA plates [21,28]. Polysaccharides anchored on proteins can be directly immobilized on ELISA plates along with polysaccharide-free control proteins. Alternatively, non-protein molecules can be chemically engineered and covalently conjugated to plate surface or microbeads. We immobilized phosphatidylserine on ELISA plates with an organic solvent and demonstrated the application of ORF phage display by identifying 13 phosphatidylserine-binding proteins and independently verifying 3 of them [21].

3.4. Autoantigen biomarkers

Autoantigens are of considerable interest for many diseases with autoantibody responses, including autoimmune diseases [34], cancers [35,36] and degenerative diseases [37]. Autoantigens not only are important disease biomarkers [34,36], but also will advance our understanding of the underlying mechanisms of autoimmune diseases. Quantification of serological autoantibodies requires pre-identification of their autoantigens. Various technologies have been developed to identify unknown autoantigens, including protein microarray, phage display, mass spectrometry and SEREX (serological identification of antigens by recombinant expression cloning) technologies [10,35,36,38]. Protein microarray is too costly for large-scale screening to identify disease-associated autoantigens, and mass spectrometry is too complicated to identify unknown autoantigens [35]. Yeast two-hybrid system is not suitable for this application. Compared with other technologies, phage display with multi-round selection and amplification has the advantage for sensitive and efficient detection of less abundant autoantigens.

Although conventional phage display, including phage microarray, has been used to identify autoantigens for different diseases [10,39], the drawback is that the majority of the identified phage clones are non-ORFs encoding unnatural peptides or mimotopes (mimicking epitopes) with no biological implication [9,10]. The interpretation of autoantibody binding to these mimotopes is problematic. We demonstrated the application of ORF phage display to identify real autoantigens for autoimmune uveitis, an autoimmune disease in the eye, and independently validated the identified autoantigens by Western blot using purified recombinant autoantigens [24]. These results suggested that ORF phage display can improve our ability to efficiently identify real autoantigens as disease biomarkers. The ORF peptide library can also be used for autoantigen identification [23]. However, because of short peptides in the library, identified clones likely encode linear antigenic epitopes, rather than conformational epitopes.

3.5. Protein-cell interactions

3.5.1. Phagocytosis-based functional selection

We chose to demonstrate the unique application of ORF phage display for protein-cell interactions, to which all other available technologies, including mass spectrometry, yeast two-hybrid system and protein microarray, are not applicable. This is an example of functional selection for ORF phage display.

Phagocytosis of apoptotic cells or cellular debris plays crucial roles in many biological processes, including morphogenesis, cell homeostasis, injury repair, immune tolerance and resolution of inflammation in multicellular organisms [40,41]. Defects in phagocytosis can lead to diseases, such as retinal degeneration, autoimmune diseases, and neurodegeneration [41,42]. Phagocytosis ligands control the initiation of the event and hold key to in-depth understanding of physiological and pathological roles of various phagocytes [41]. However, phagocytosis ligands are traditionally identified on a case-by-case basis with daunting technical challenges. Consequently, knowledge gap in molecular phagocyte biology and phagocytosis ligands has hindered our capability to harness their therapeutic potentials in disease conditions [41].

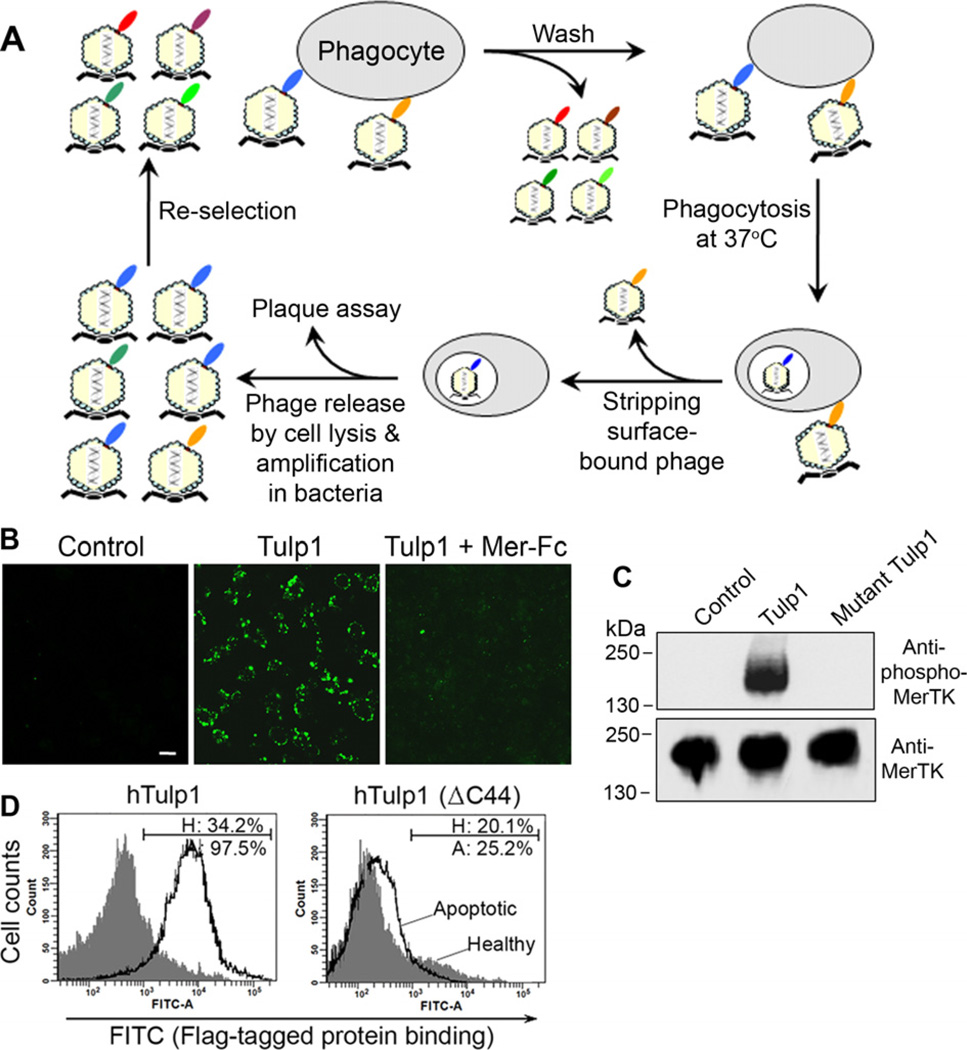

We developed a novel strategy of phagocytosis-based functional selection to identify unknown phagocytosis ligands in the absence of receptor information (Fig. 3A) and identified 9 putative phagocytosis ligands, including tubby-like protein 1 (Tulp1) [15]. Biological relevance is of the critical importance for ORF phage display. We demonstrated that Tulp1 is a biologically relevant phagocytosis ligand with the following data [15,43]. (a) Purified recombinant Tulp1 was independently verified to facilitate the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells or cellular debris (Fig. 3B); (b) Tulp1 was characterized as a new ligand with binding activity to the well-known phagocytic receptor of Mer receptor tyrosine kinase (MerTK); (c) Tulp1 induced MerTK activation with receptor autophosphorylation and intracellular signaling cascade (Fig. 3C); (d) Excess soluble MerTK extracellular domain blocked Tulp1-induced phagocytosis (Fig. 3B); (e) Five K/R(X)1–2KKK motifs in the N-terminal region of Tulp1 were mapped as essential MerTK-binding domain; (f) Mutation of all these five motifs to K/R(X)1–2AAA abolished Tulp1-induced phagocytosis, MerTK binding and MerTK activation (Fig. 3C); (g) Tulp1 was characterized as a bridging molecule with its N-terminal region binding to MerTK and the C-terminal phagocytosis prey-binding domain (PPBD) interacting with apoptotic cells, but not healthy cells (Fig. 3D). The specific binding of Tulp1 to apoptotic cells was necessary for their selective clearance by phagocytosis; (h) Tubby in the same protein family was characterized with structural and functional similarities [43]. These findings demonstrated that Tulp1 is a genuine phagocytosis ligand, which in turn supports the validity of ORF phage display to identify functionally relevant cellular ligands in the absence of receptor information. The identified ligands, such as Tulp1, can be used as molecular probes to identify their receptors. Phagocytosis-based functional selection by ORF phage display is applicable to other professional and non-professional phagocytes.

Fig. 3.

Phagocytosis-based affinity selection. (A) The scheme for the functional selection. (B) Recombinant Tulp1 facilitates phagocytosis by retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells. Fluorescence-labeled plasma membrane vesicles were incubated with RPE cells for phagocytosis in the presence or absence of Tulp1 and excess Mer-Fc (MerTK extracellular domain fused to human IgG1 Fc domain), washed and analyzed for phagocytosed vesicles by confocal microscopy. Bar = 10 µm. (C) Tulp1 activates MerTK with receptor autophosphorylation. D407 RPE cells were treated with purified Tulp1 or mutant Tulp1 with all five K/R(X)1–2KKK mutated to K/R(X)1–2AAA. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot using anti-phospho-MerTK and anti-MerTK antibodies. (D) Tulp1 specifically binds to apoptotic cells. FLAG-tagged human Tulp1 and its mutant with deletion of C-terminal 44 amino acids [hTulp1(ΔC44)] were purified and analyzed for their binding to apoptotic and healthy Jurkat cells by flow cytometry. H, healthy cells; A, apoptotic cells. This figure is reproduced with permission from Refs. [15,43].

3.5.2. Dual functional cloning

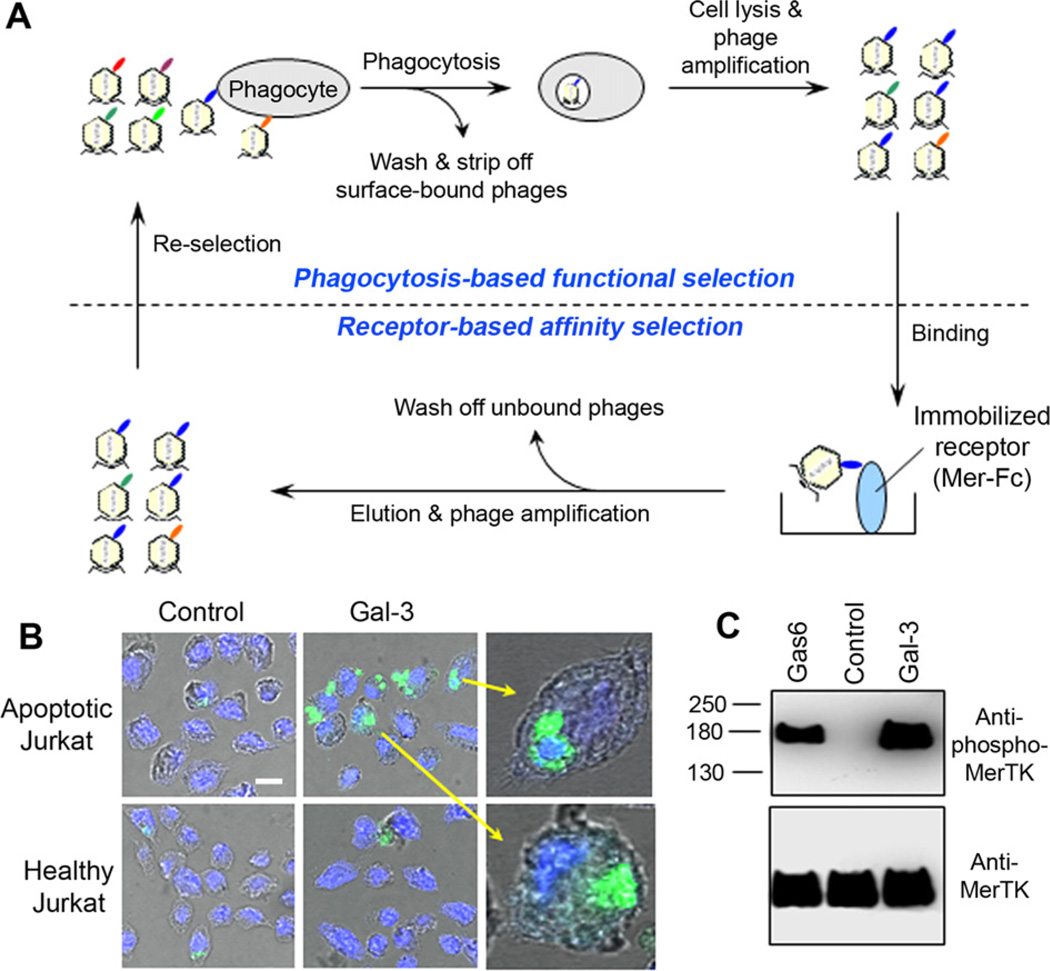

Similar to the identification of phagocytosis ligands in the absence of receptor information, the identification of receptor-specific phagocytosis ligands is equally challenging. Several phagocytic receptors, such as TREM2 and SIRPβ1, still lack a known ligand [42]. Although other receptors have one or two known ligands, we really do not know how many more ligands are yet to be identified. To address these difficulties, we further developed a dual functional cloning strategy by combining phagocytosis-based functional selection with receptor-based affinity selection (Fig. 4A) [44]. The former selection enriched biologically relevant ligands with the capacity to activate their receptors for cellular internalization, and the latter selected the ligands with receptor-binding specificity. We demonstrated the feasibility of dual functional cloning by identifying Tulp1 and galectins-3 (Gal-3) as MerTK-specific phagocytosis ligands [44]. Gal-3 was independently verified as a new MerTK ligand with the capacity to induce phagocytosis of apoptotic cells and MerTK autophosphorylation (Fig. 4B and C). Excess soluble MerTK extracellular domain blocked Gal-3-induced phagocytosis [44]. These results suggested that dual functional cloning is a valid approach for unbiased identification of receptor-specific phagocytosis ligands with biological relevance. Together, phagocytosis-based functional selection and dual functional cloning with applicability to many other phagocytes and phagocytic receptors will advance our understanding of molecular phagocyte biology, thereby improving our ability to exploit the therapeutic potentials of various phagocytes [41].

Fig. 4.

Dual functional cloning. (A) The scheme of dual functional cloning for MerTK-specific ligands. (B) Gal-3 facilitates phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages. Apoptotic and healthy Jurkat cells were labeled with green fluorescence, washed, incubated with J774 macrophages in the presence or absence of Gal-3 and analyzed by confocal microscopy. The confocal images of phagocytosed cells (green) and nuclei (blue) are superimposed with the cognate bright fields to reveal the internalized Jurkat cells. Bar = 10 µm. (C) Gal-3 induces MerTK activation. MerTK activation induced by Gal-3 was analyzed as in Fig. 3C. Gas6 is a known MerTK ligand as a positive control. This figure is reproduced with permission from Ref. [44].

3.6. Protease substrates

Phage display with random peptide libraries has been used to map the substrate specificity of proteases [45,46]. However, the identified mimotopes have minimal biological implication in protease pathways. We demonstrated that ORF phage display can be used to identify endogenous protease substrates, rather than mimotopes, to facilitate the delineation of protease functions (Fig. 5) [47]. However, the drawback of ORF phage display in this application is that the protease cleavage sites are unknown. Mass spectrometry has the capacity of mapping the approximate cleavage sites for proteases [48]. The advantages of ORF phage display are its sensitivity in detecting less abundant substrates and its convenience for repetitively quantifying substrate specificity with identified phage clones to avoid laborious purification of recombinant substrates [47].

Fig. 5.

Selection of protease substrates by ORF phage display. ORF phage display cDNA library with C-terminal biotin binds to streptavidin immobilized on ELISA plates. After washing, bound phages are eluted by protease cleavage, amplified, and used as input for the next round of selection. Phages enriched by multi-round selection can be individually isolated, amplified and verified for their release activity by protease cleavage.

3.7. Other applications

Conventional phage display has been reported with many other applications over the past two decades [1,49]. ORF phage display is applicable to most of these applications to efficiently map cellular protein functions. For example, ORF phage display can be used to identify cellular binding proteins not only for lipids, polysaccharides, RNA and DNA as discussed but also for multimolecular complexes, such as viruses and whole cells [50,51]. ORF phage display can also be used to identify endogenous ligands with specific binding activity to neovascular vessels by in vivo selection [52]. Other functional selections include identification of substrates for tyrosine kinases [53]. Rather than identifying mimotopes by conventional phage display, ORF phage display will efficiently identify real endogenous proteins with specific binding or functional activities.

4. Conclusions

ORF phage display reinvigorates the old technology of phage display with a new capability to map diverse functions of cellular proteins. As a result, ORF phage display can be used as a new technology of functional proteomics with versatile applications, including the unique applications of phagocytosis-based functional cloning and dual functional cloning. Next generation sequencing will further improve the efficiency of ORF phage display. Compared with yeast two-hybrid system, mass spectrometry and protein microarray, ORF phage display with multi-round selection and amplification will sensitively enrich and identify less abundant cellular proteins. In a sense, the new technology is an equivalent of “protein-PCR” for the amplification and identification of cellular proteins based on their functional activities rather than DNA sequences. Similarly, dual functional selection is analogous to “nest protein-PCR”, in which different functional selections could be coupled with affinity selection to improve the reliability and specificity of ORF phage display to delineate cellular protein functions.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported in part by NIH grant R01GM094449-01A1, R01EY016211-05S1 and Florida Department of Health James and Esther King Biomedical Research Program 1KF01-38241. The author thanks Dr. N. Caberoy for discussion.

References

- 1.Kehoe JW, Kay BK. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:4056–4072. doi: 10.1021/cr000261r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paschke M. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006;70:2–11. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0270-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pande J, Szewczyk MM, Grover AK. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010;28:849–858. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith GP. Science. 1985;228:1315–1317. doi: 10.1126/science.4001944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bratkovic T. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2010;67:749–767. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0192-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schirrmann T, Meyer T, Schutte M, Frenzel A, Hust M. Molecules. 2011;16:412–426. doi: 10.3390/molecules16010412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li W, Caberoy NB. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;85:909–919. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2277-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbas CF, 3rd, Burton DR, Scott JK, Silverman GJ. Phage Display: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalnina Z, Silina K, Meistere I, Zayakin P, Rivosh A, Abols A, Leja M, Minenkova O, Schadendorf D, Line A. J. Immunol. Methods. 2008;334:37–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin HS, Talwar HS, Tarca AL, Ionan A, Chatterjee M, Ye B, Wojciechowski J, Mohapatra S, Basson MD, Yoo GH, Peshek B, Lonardo F, Pan CJ, Folbe AJ, Draghici S, Abrams J, Tainsky MA. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2396–2405. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crameri R, Suter M. Gene. 1993;137:69–75. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90253-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenberg A, Griffin K, Studier FW, McCormick M, Berg J, Novy R, Mierendorf R. Innovations. 1996;6:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jestin JL. Biochimie. 2008;90:1273–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garufi G, Minenkova O, Lo Passo C, Pernice I, Felici F. Biotechnol. Annu. Rev. 2005;11:153–190. doi: 10.1016/S1387-2656(05)11005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caberoy NB, Maiguel D, Kim Y, Li W. Exp. Cell Res. 2010;316:245–257. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ansuini H, Cicchini C, Nicosia A, Tripodi M, Cortese R, Luzzago A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e78. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnf077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zacchi P, Sblattero D, Florian F, Marzari R, Bradbury AR. Genome Res. 2003;13:980–990. doi: 10.1101/gr.861503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Niro R, Sulic AM, Mignone F, D’Angelo S, Bordoni R, Iacono M, Marzari R, Gaiotto T, Lavric M, Bradbury AR, Biancone L, Zevin-Sonkin D, De Bellis G, Santoro C, Sblattero D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e110. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krumpe LR, Atkinson AJ, Smythers GW, Kandel A, Schumacher KM, McMahon JB, Makowski L, Mori T. Proteomics. 2006;6:4210–4222. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caberoy NB, Zhou Y, Jiang X, Alvarado G, Li W. J. Mol. Recognit. 2010;23:74–83. doi: 10.1002/jmr.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caberoy NB, Zhou Y, Alvarado G, Fan X, Li W. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;386:197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nallamsetty S, Kapust RB, Tozser J, Cherry S, Tropea JE, Copeland TD, Waugh DS. Protein Expr. Purif. 2004;38:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larman HB, Zhao Z, Laserson U, Li MZ, Ciccia A, Gakidis MA, Church GM, Kesari S, Leproust EM, Solimini NL, Elledge SJ. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:535–541. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim Y, Caberoy NB, Alvarado G, Davis JL, Feuer WJ, Li W. Clin. Immunol. 2011;138:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins MO, Choudhary JS. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2008;19:324–330. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suter B, Kittanakom S, Stagljar I. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2008;19:316–323. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carroll K, Gomez C, Shapiro L. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:55–63. doi: 10.1038/nrm1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakai Y, Nomura Y, Sato T, Shiratsuchi A, Nakanishi Y. J. Biochem. 2005;137:593–599. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvi072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deng SJ, MacKenzie CR, Sadowska J, Michniewicz J, Young NM, Bundle DR, Narang SA. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:9533–9538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Danner S, Belasco JG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:12954–12959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211439598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gargir A, Ofek I, Meron-Sudai S, Tanamy MG, Kabouridis PS, Nissim A. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1569:167–173. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(01)00245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cicchini C, Ansuini H, Amicone L, Alonzi T, Nicosia A, Cortese R, Tripodi M, Luzzago A. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;322:697–706. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00851-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stace CL, Ktistakis NT. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1761:913–926. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyons R, Narain S, Nichols C, Satoh M, Reeves WH. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005;1050:217–228. doi: 10.1196/annals.1313.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caron M, Choquet-Kastylevsky G, Joubert-Caron R. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:1115–1122. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R600016-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kijanka G, Murphy D. J. Proteomics. 2009;72:936–944. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colasanti T, Barbati C, Rosano G, Malorni W, Ortona E. Autoimmun. Rev. 2010;9:807–811. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jager D SEREX. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;360:319–326. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-165-7:319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Babel I, Barderas R, Diaz-Uriarte R, Moreno V, Suarez A, Fernandez-Acenero MJ, Salazar R, Capella G, Casal JI. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2011;10 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.001784. M110001784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Erwig LP, Henson PM. Am. J. Pathol. 2007;171:2–8. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li W. J. Cell Physiol. 2012;227:1291–1297. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neumann H, Takahashi K. J. Neuroimmunol. 2007;184:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caberoy NB, Zhou Y, Li W. EMBO J. 2010;29:3898–3910. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caberoy NB, Alvarado G, Bigcas JL, Li W. J. Cell Physiol. 2012;227:401–407. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Diamond SL. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2007;11:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matthews DJ, Wells JA. Science. 1993;260:1113–1117. doi: 10.1126/science.8493554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caberoy NB, Alvarado G, Li W. Molecules. 2011;16:1739–1748. doi: 10.3390/molecules16021739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Agard NJ, Wells JA. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2009;13:503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sidhu SS. Phage Display in Biotechnology and Drug Discovery. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rajik M, Jahanshiri F, Omar AR, Ideris A, Hassan SS, Yusoff K. Virol. J. 2009;6:74. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Akita N, Maruta F, Seymour LW, Kerr DJ, Parker AL, Asai T, Oku N, Nakayama J, Miyagawa S. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:1075–1081. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00291.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Valadon P, Garnett JD, Testa JE, Bauerle M, Oh P, Schnitzer JE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:407–412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506938103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmitz R, Baumann G, Gram H. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;260:664–677. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]