Abstract

C2-Arylethynyladenosine-5′-N-methyluronamides containing a bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane [(N)-methanocarba] ring are selective A3 adenosine receptor (AR) agonists. Similar 4′-truncated C2-arylethynyl-(N)-methanocarba nucleosides containing alkyl or alkylaryl groups at the N6 position were low-efficacy agonists or antagonists of the human A3AR with high selectivity. Higher hA3AR affinity was associated with N6-methyl and ethyl (Ki = 3–6 nM) than with N6-arylalkyl groups. However, combined C2-phenylethynyl and N6-2-phenylethyl substitutions in selective antagonist 15 provided a Ki of 20 nM. Differences between 4′-truncated and nontruncated analogues of extended C2-p-biphenylethynyl substitution suggested a ligand reorientation in AR binding, dominated by bulky N6 groups in analogues lacking a stabilizing 5′-uronamide moiety. Thus, 4′-truncation of C2-arylethynyl-(N)-methanocarba adenosine derivatives is compatible with general preservation of A3AR selectivity, especially with small N6 groups, but reduced efficacy in A3AR-induced inhibition of adenylate cyclase.

Keywords: G protein-coupled receptor, purines, molecular modeling, structure−activity relationship, radioligand binding, adenosine receptor

Extracellular adenosine acts in cell signaling through four subtypes of rhodopsin-like G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), that is, A1 adenosine receptor (AR), A2AAR, A2BAR, and A3AR.1 The A3AR is the least widely distributed of the subtypes in the body and has become a target in drug discovery for various disease conditions.2−4 A3AR-selective agonists have successfully progressed to phase 2 and 3 clinical trials for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (including subsequent to hepatitis C viral infection), autoimmune inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and osteoarthritis, glaucoma, and dry eye disease. A3AR agonists are also under consideration for treating uveitis, Crohn's disease, neuropathic pain, loss of skin pigmentation, lung injury, and ischemia of brain, heart, and skeletal muscle.2,5−7 A3AR-selective antagonists are being explored for treatment of asthma, septic shock, glaucoma, and other conditions.8−14

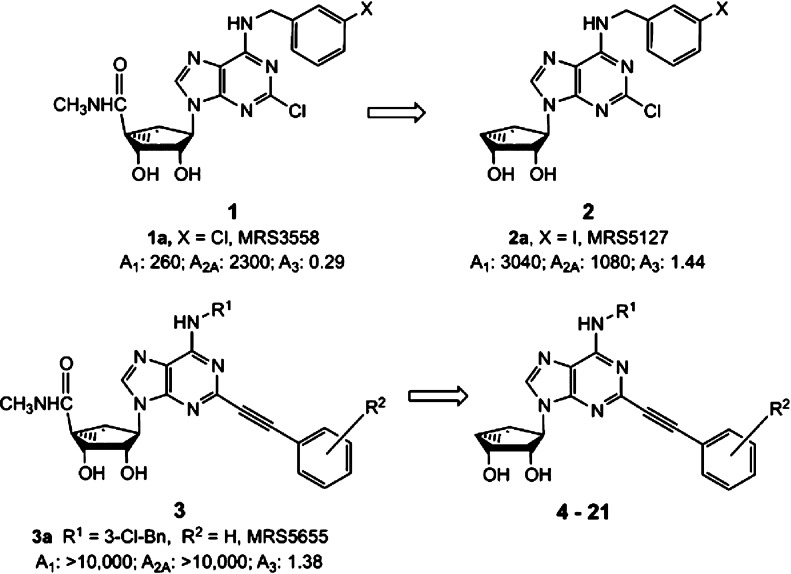

The structure–activity relationship (SAR) of nucleosides at the A3AR has been extensively explored.4 Selective agonists of the A3AR are typically adenine-9-ribosides containing both 5′-N-methyluronamide (facilitates complete activation of A3AR) and N6-(3-halobenzyl) groups. A general means of enhancing A3AR affinity and selectivity is the replacement of the flexible ribose ring with a conformationally constrained bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane (methanocarba) ring system that enforces a receptor-preferred North (N) conformation,15,16 as in the selective agonist 1a (MRS3558) and its congeners (Chart 1).

Chart 1. (N)-Methanocarba-adenosine Derivatives as Selective A3AR Ligands (hAR Affinity in nM): Full Agonists in the 5′-N-Methyluronamide Series (1 and 3) and Truncated Nucleosides (2) That Act as A3AR Antagonists and Partial Agonists, Including the Present Target Structures (4–21).

The effects of truncation of adenosine derivatives at the 4′ carbon, that is, loss of the CH2OH of adenosine, have been extensively explored in the 4′-thio, 4′-oxo, and (N)-methanocarba series of nucleosides. An effect of this truncation is typically retention of affinity at the A3AR and reduction of affinity at other AR subtypes.17−19 Specifically, in the (N)-methanocarba series of N6-(3-halobenzyl) derivatives, that is, full A3AR agonists 1, truncation resulted in series 2 that retains hA3AR affinity and selectivity but is typically reduced in efficacy at A3 and A1ARs but not A2AAR.20 The functional activity of 2a (MRS5127) and its congeners range from full competitive antagonism (KB = 8.9 nM,19 by Schild analysis in blocking agonist-induced guanine nucleotide binding) to partial agonism of ∼50% efficacy (in inhibition of adenylate cyclase). Compound 2a was radioiodinated and studied in binding to ARs in different species,21 and its high affinity and selectivity for the A3AR were independent of species.

We recently demonstrated that (N)-methanocarba adenosine 5′-N-methyluronamide derivatives tolerate the introduction of rigid, extended C2-arylalkynyl groups.22,22b Previously, similar groups were included in potent A3AR agonists in the relatively flexible riboside series.23 In the rigid (N)-methanocarba series, the much larger planar groups, such as large as 2-pyrenylethynyl, than anticipated were tolerated at the human (h) A3AR.

The present study establishes that truncation of the 4′ group of 2-arylethynyl-(N)-methanocarba adenosine agonists in general preserves selectivity for the A3AR, while the effects of such truncation on the relative agonist efficacy at this receptor are complex. These truncated partial agonists/antagonists of the A3AR have favorable physicochemical properties, such as low polarity, which will likely alter pharmacokinetic behavior in vivo. The SAR in AR binding of 4′-truncated (N)-methanocarba-adenosine derivatives was characterized by Melman et al.19 and Tosh et al.22b The derivatives contained mainly N6-3-halobenzyl groups and relatively flexible, straight chain alkynyl groups at the C2 position, such as 2d (Table 1), but substitution with rigid, linear C2-arylethynyl groups was not included in the previous studies. We have explored such rigid C2 substituents in the present study and also varied the N6 group.

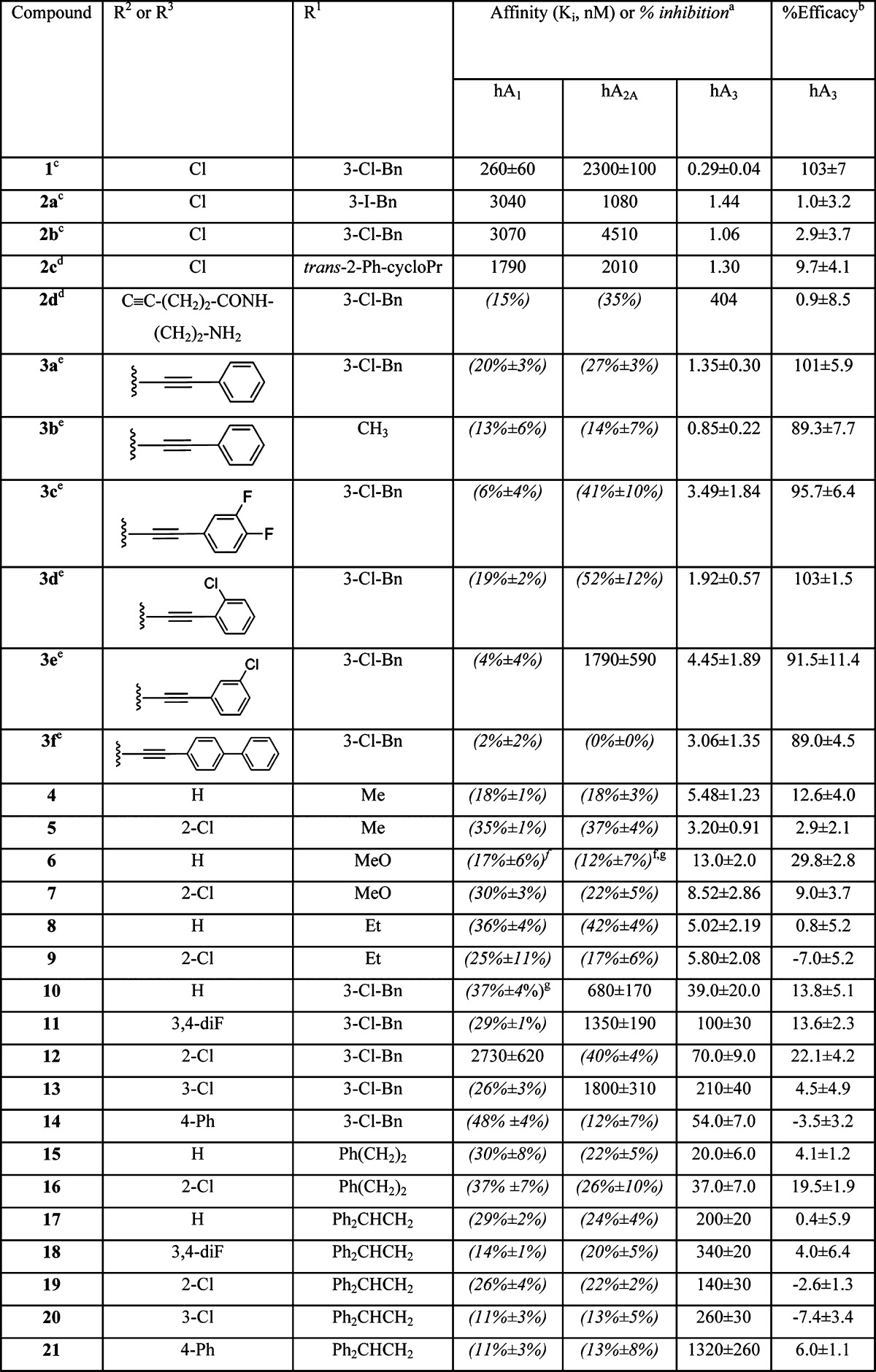

Table 1. Affinity of a Series of (N)-Methanocarba adenosine Derivatives at hARs and Functional Efficacy at the hA3AR.

Binding in membranes of CHO or HEK293 (A2A only) cells stably expressing one of three hAR subtypes. The binding affinity for hA1, A2A, and A3ARs was expressed as Ki values using agonists [3H]N6-R-phenylisopropyladenosine, [3H]2-[p-(2-carboxyethyl)phenyl-ethylamino]-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine, or [125I]N6-(4-amino-3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide, respectively. A percent in parentheses refers to inhibition of binding at 10 μM.

Inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP production in hA3AR-transfected CHO cells. At 10 μM, in comparison to the maximal effect of 10 μM 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (=100%). Selected compounds (10 μM) were evaluated for stimulation of cyclic AMP production (% of full agonist 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine) in hA2BAR-transfected CHO cells: 3c, 28 ± 3; 3e, 28 ± 4; 5, 49 ± 7; 6, 38 ± 3; 9, 44 ± 10; 10, 33 ± 11; 13, 40 ± 9; and 15, 46 ± 14. Data are expressed as means ± standard errors (n = 3, unless noted).

Data from Melman et al.19

Data from Tosh et al.30

Inhibition of radioligand binding at 1 μM.

n = 2.

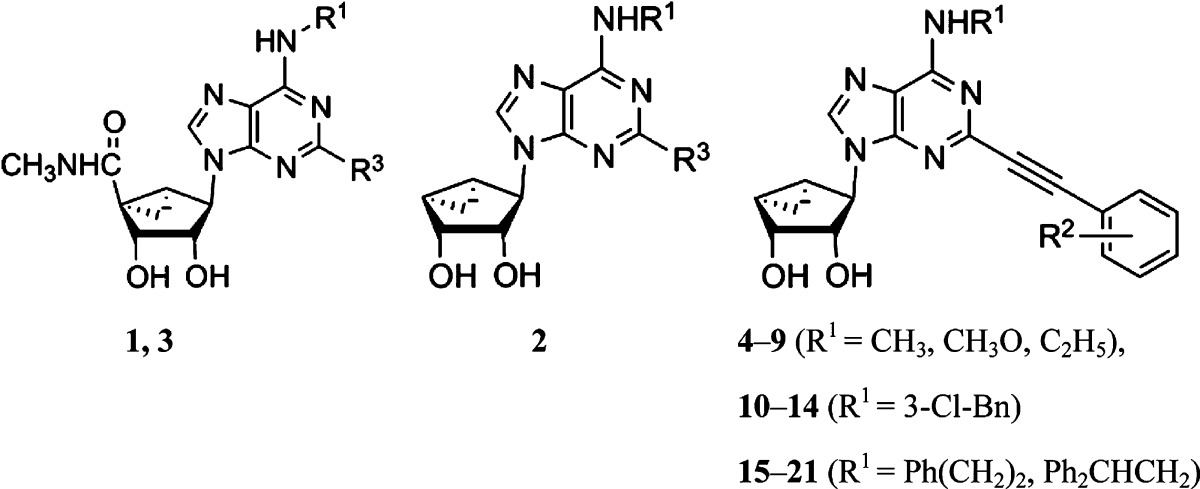

The 4′-truncated analogues contain varied N6 substitution (N6-methyl, methoxy, or ethyl: 4–9; N6-3-chlorobenzyl: 10–14; and N6-2-phenylethyl or 2,2-diphenylethyl: 15–21) (Table 1). With small N6 substitution, only two phenylethynyl variations were placed at the C2 position: unsubstituted and 2-chloro, which was previously shown to promote A3AR affinity.22,22b However, in the N6-3-chlorobenzyl series, several other C2-phenylethynyl substitutions were used, that is, 3,4-difluoro (11), 3-chloro (13), and 4-phenyl (14). N6-Methyl and adenosines are typically more potent at the hA3AR than rat (r) A3AR, while N6-(3-halobenzyl)adenosines tend to display greater species-independent selectivity.21 Thus, it is useful to have a range of N6 groups present.

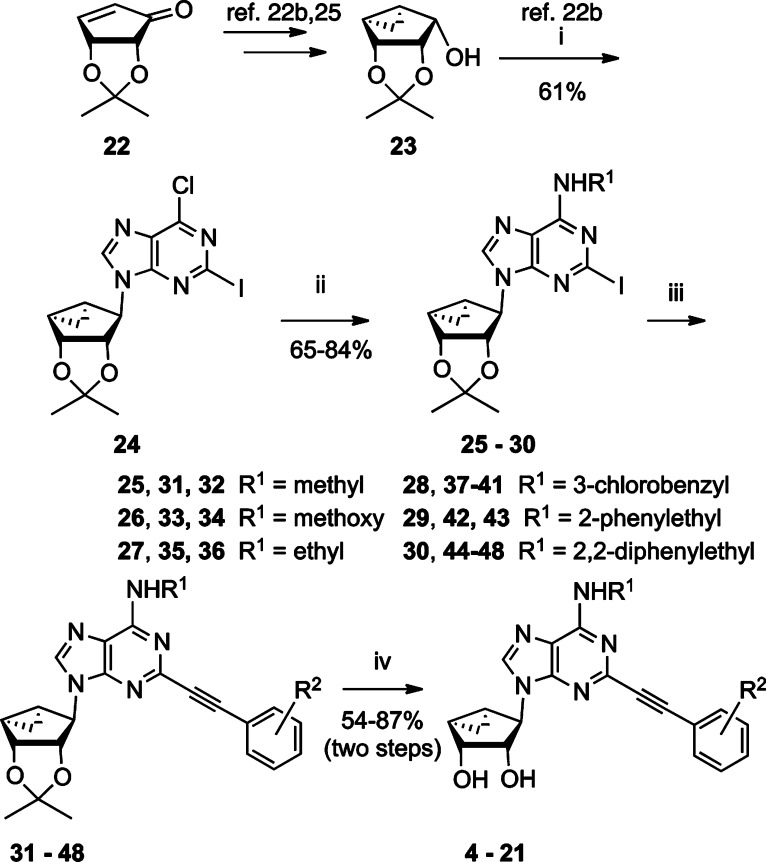

The synthetic route used to prepare truncated (N)-methanocarba derivatives containing a C2-arylethynyl group is shown in Scheme 1. Initially, d-ribose was converted as previously reported into the 2′,3′-protected intermediate cyclopentenone 22.25 Compound 22 was then converted stereoselectively in two steps to the alcohol 23, which was subjected to a Mitsunobu reaction with 2-iodo-6-chloropurine to give intermediate 24.26,30 Nucleophilic substitution with the appropriate amine at room temperature provided the N6-substituted intermediates 25–30. A Sonogashira reaction24 was then carried out with a variety of commercially available phenylalkynes, followed by acid hydrolysis of the 2′,3′-isopropylidene group to provide truncated nucleosides 4–21.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Truncated (N)-Methanocarba-adenosine Analogues.

Reagents: (i) 2-Iodo-6-chloropurine, Ph3P, DIAD, THF, rt. (ii) R1NH2, Et3N, MeOH, rt. (iii) Substituted HC≡C-Ph-R2, Pd(PPh3)2Cl2, CuI, Et3N, DMF, rt. (iv) 50% TFA (aq.), MeOH:CH2Cl2 (3:1), rt.

Radioligand binding assays were performed at three hAR subtypes using standard 3H- and 125I-labeled nucleoside ligands of high affinity (Table 1).19 A3AR binding curves of the truncated nucleosides generally showed a Hill coefficient of ∼1. Selected compounds in the (N)-methanocarba nucleoside series were assayed at the hA2BAR and found to be weakly active, as this ring system was previously found to reduce hA2BAR affinity.15 Some previously reported 2-chloro (2a–c) and 2-alkynyl (2d and 3a–f) (N)-methanocarba-adenosine derivatives were used for comparison in the biological assays.16,22,22b,27

The N6-methyl C2-phenylethynyl analogue 4 displayed a Ki value of 5.5 nM in binding to the hA3AR and was nearly inactive at the hA1AR and hA2AAR with only 18% inhibition of binding at 10 μM. Therefore, the degree of A3AR selectivity of 4 was estimated to be >2000-fold. A variety of other 4′-truncated C2-arylethynyl-(N)-methanocarba nucleosides containing N6-methoxy, N6-ethyl, N6-3-chlorobenzyl, N6-2-phenylethyl, or N6-2,2-diphenylethyl groups displayed a range of high-to-moderate affinities at the hA3AR and generally with A3AR selectivity. The hA3AR affinity of these derivatives demonstrated a freedom of substitution at C2. The smaller groups at N6 in 4–9 were associated with higher affinity at the A3AR. Thus, N6-methyl (5, Ki = 3.2 nM) and ethyl (9, Ki = 5.8 nM) in the set of 2-(2-chlorophenylethynyl) derivatives provided the highest hA3AR affinity with only weak binding to A1 and A2AARs, implying a selectivity of ≥1000-fold, and a N6-methoxy derivative 7 was slightly less potent. In the N6-3-chlorobenzyl series, the unsubstituted phenylethynyl derivative 10 was the most potent in binding at the A3AR (Ki = 39 nM). However, unlike the 5′-N-methyluronamide series, halo substitution in 3,4-difluorophenylethynyl 11 and 2-chlorophenylethynyl 12 analogues significantly reduced A3AR affinity. N6-2-Phenylethyl substitution in C2-phenylethynyl analogue 15 provided a Ki value of 20 nM at the hA3AR. A 2-p-biphenylethynyl substitution was well tolerated at the A3AR in the N6-3-chlorobenzyl 14 but not N6-(2,2-diphenylethyl) 21 series.

At the hA1AR, only 10–40% of binding inhibition was typically seen at 10 μM for a variety of substitutions, except for the 2-chlorophenylethynyl analogue 12 (Ki = 2.7 μM). However, the variability of affinity upon substitution of the arylethynyl moiety was greater at hA2AAR than at hA1AR. For example, three N6-3-chlorobenzyl compounds (10, 11, and 13) had Ki values in the range of 0.7–1.8 μM at the hA2AAR. As in the 5′-N-methyluronamide series,22,22b hA2AAR affinity increased substantially upon replacement with a C2-(3-chlorophenylethynyl) group in 13, leading to only 8.6-fold selectivity in A3AR binding.

Functional data were determined at a single, saturating concentration (10 μM) in an assay of hA3AR-induced inhibition of the forskolin-stimulated production of adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cyclic AMP) in membranes of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells expressing the hA3AR (Table 1).26 Inhibition by 10 μM 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA) was set at 100% relative efficacy. The novel truncated derivatives were generally low-efficacy partial agonists (e.g., 6, 12, and 16) or antagonists of the hA3AR. Although N6-ethyl and 2,2-diphenylethyl derivatives tended to be antagonists of the hA3AR, N6-methyl derivative 4 and N6-methoxy derivative 6 had significant residual efficacy. The efficacy of N6-Cl-benzyl and 2-phenylethyl derivatives 10–17 varied depending on the substitution of the phenylethynyl group. The highly selective ligands 10 and 15 displayed 14% and 4% relative efficacy, respectively.

Because of the sterically bulky hydrocarbon group at the C2 position, these compounds display increased hydrophobicity in comparison to previously described truncated adenosine analogues. The large differences in steric bulk and hydrophobicity with respect to the conventional ribonucleoside series could influence the pharmacokinetics and the spectrum of biological activities at the A3AR. For example, the cLog P values of potent C2-arylethynyl derivatives having N6-methyl 5, N6-3-chlorobenzyl 10, N6-2-phenylethyl 15, and N6-2,2-diphenylethyl 17 substituents were 2.32, 3.76, 3.70, and 5.14, respectively. The total polar surface area of all four derivatives was 92.8 Å2, which is within the desired range.28 These physicochemical parameters are predicitive of bioavailability, although in vivo pharmacological and pharmacokinetic properties of these analogues have not been measured.

Flexibility of a 5′-N-alkyluronamido moiety of adenosine agonists, which is entirely lacking in the present analogues, is closely associated with full A3AR activation. Consistently, these analogues have low or minimal levels of efficacy in the A3AR-induced inhibition of adenylate cyclase, but the functional efficacy for other effector systems coupled to the same receptor has not been measured. For comparison, other truncated (N)-methanocarba-adenosine derivatives were shown to be full antagonists in a guanine nucleotide binding assay, which is relatively poorly coupled, and partial agonists in an assay of cyclic AMP.21 The unusual shape of these nucleoside ligands might translate to ligand-dependent differences in the conformation of the nucleoside-bound A3AR, which could have functional implications on effects induced by this receptor. There is already an indication that nucleoside ligands of the A3AR can display a functional bias.29

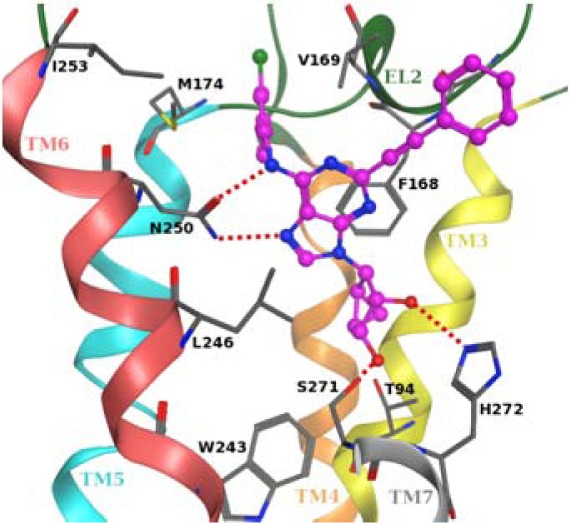

The observation of high affinity at the A3AR in the 5′-N-methyluronamido series was explained in terms of a proposed outward shift of transmembrane helix 2 (TM2) from its position in a homology model based on the agonist-bound A2AAR structure.22,22b The present 4′-truncated derivatives were subjected to similar molecular modeling analysis (Supporting Information) to predict a similar 7 Å shift of TM2, similar to its position in opsin, to accommodate the bulky, extended C2 substituent. As for the 5′-N-methyluronamides,22,22b the 3′- and 2′-hydroxyl groups of docked 10 formed H-bonds with Ser271 (7.42) and His272 (7.43) side chains, respectively. The side chain of Asn250 (6.55) strongly interacted with the 6-amino group and the adenine N7 atom. Moreover, the adenine ring was anchored inside the binding site by a π–π stacking interaction with Phe168 (EL2) and strong hydrophobic contacts with Leu246 (6.51) and Ile268 (7.39). Substituents at the N6 (TM5, TM6, and EL2) and C2 positions (TM2 and EL1) were located in hydrophobic extracellular portions of the hA3AR binding pocket. While the 5′-N-methyluronamides22,22b were able to form a H-bond with the side chain hydroxyl group of Thr94 (3.36), truncation prevented an interaction with this key residue, a putative explanation of the low efficacy profile of these 4′-truncated nucleosides.

In the 5′-N-methyluronamido series, an enhancement of A2AAR affinity was observed for 2-(3-chlorophenylethynyl) analogues, which suggested halogen–π interactions with Tyr9 (1.35) and Tyr272 (7.36) of the A2AAR.22,22b In the present truncated series, compound 13 contained the same C2-(3-chlorophenylethynyl) group, and the A2AAR affinity was enhanced, likely reflecting a common interaction with the same site on the hA2AAR. However, 2-(3-chlorophenylethynyl) derivative 20 did not display this characteristic enhancement, suggesting a reorientation of the bound ligand, likely stemming from the bulky N6-2,2-diphenylethyl group and the lack of stabilizing 5′-uronamido interactions.

In conclusion, we have found a new series of highly potent and selective, low-efficacy partial agonists (e.g., 6 and 16) or antagonists (e.g., 5, 8, 9, and 15) at the A3AR, containing combined arylethynyl groups at the adenine C2 position and varied N6 substitution. The binding affinities demonstrated tolerance of steric bulk on the extended C2 position substituents, allowed by a proposed plasticity of the A3AR.22,22b Smaller N6 substitutuents, such as methyl and ethyl, provided higher A3AR affinity than N6-arylalkyl substitutuents. This difference contrasts with the analogues having an additional receptor anchor, that is, the 5′-N-methyluronamido group in the region of TMs 3 and 7, for which the A3AR affinity was less dependent on the N6 substitutuent. Overall, truncation of the 4′ group of 2-arylethynyl-(N)-methanocarba adenosine derivatives was shown to be compatible with retention of A3AR selectivity. Substitution of the phenylethynyl group modulated the agonist efficacy (0–30% of full agonism in adenylate cyclase inhibition) at this receptor in a complex manner. These potent, truncated ligands that have improved druglike physical properties and should be useful in future pharmacological studies of the action of this receptor in disease models of the cardiovascular, inflammatory, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, and central nervous systems and in studies that relate ligand structure (and possibly receptor conformation) to functional selectivity of GPCR action.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. John Lloyd and Dr. Noel Whittaker (NIDDK) for mass spectral determinations.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AR

adenosine receptor

- cyclic AMP

adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- DIAD

diisopropyl azodicarboxylate

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- NECA

5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- TM

transmembrane helix

Supporting Information Available

Procedures for chemical synthesis (with selected spectra), biological assays, and molecular modeling. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to this manuscript and have given approval to its final version.

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIDDK.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Fredholm B. B.; IJzerman A. P.; Jacobson K. A.; Linden J.; Müller C. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors—An update. Pharmacol. Rev. 2011, 63, 1–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman P.; Bar-Yehuda S.; Liang B. T.; Jacobson K. A. Pharmacological and therapeutic effects of A3 adenosine receptor (A3AR) agonists. Drug Discovery Today 2012, 17, 359–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessi S.; Merighi S.; Varani K.; Cattabriga E.; Benini A.; Mirandola P.; Leung E.; MacLennan S.; Feo C.; Baraldi S.; Borea P. A. Adenosine receptors in colon carcinoma tissues and colon tumoral cell lines: focus on the A3 adenosine subtype. J. Cell. Physiol. 2007, 211, 826–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessi S.; Merighi S.; Sacchetto V.; Simioni C.; Borea P. A. Adenosine receptors and cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1808, 1400–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong S. L.; Federico S.; Venkatesan G.; Mandel A. L.; Shao Y. M.; Moro S.; Spalluto G.; Pastorin G. The A3 adenosine receptor as multifaceted therapeutic target: pharmacology, medicinal chemistry, and in silico approaches. Med. Res. Rev. 2012, 10.1002/med.20254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Yehuda S.; Luger D.; Ochaion A.; Cohen S.; Patokaa R.; Zozulya G.; Silver P. B.; Garcia Ruiz de Morales J. M.; Caspi R. R.; Fishman P. Inhibition of experimental auto-immune uveitis by the A3 adenosine receptor agonist CF101. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2011, 28, 727–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madi L. L.; Korenstein R.. A3 adenosine receptor ligands for modulation of pigmentation. WO/2011/010306, 2011.

- Chen Z.; Janes K.; Chen C.; Doyle T.; Tosh D. K.; Jacobson K. A.; Salvemini D. Controlling murine and rat chronic pain through A3 adenosine receptor activation. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 1855–1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fozard J. R.From hypertension (+) to asthma: Interactions with the adenosine A3 receptors in muscle protection. In A3 Adenosine Receptors from Cell Biology to Pharmacology and Therapeutics; Borea P. A., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, 2010; Chapter 1, pp 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bulger E. M.; Tower C. M.; Warner K. J.; Garland T.; Cuschieri J.; Rizoli S.; Rhind S.; Junger W. G. Increased neutrophil adenosine A3 receptor expression is associated with hemorrhagic shock and injury severity in trauma patients. Shock 2011, 36, 435–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila M. Y.; Stone R. A.; Civan M. M. Knockout of A3 adenosine receptors reduces mouse intraocular pressure. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002, 43, 3021–3026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morschl E.; Molina J. G.; Volmer J. B.; Mohsenin A.; Pero R. S.; Hong J. S.; Kheradmand F.; Lee J. J.; Blackburn M. R. A3 adenosine receptor signaling influences pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2008, 39, 697–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsawa K.; Sanagi T.; Namakura Y.; Suzuki E.; Inoue K.; Kohsaka S. Adenosine A3 receptor is involved in ADP-induced microglial process extension and migration. J. Neurochem. 2012, 121, 217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C. B.; Lindler K. M.; Campbell N. G.; Sutcliffe J. S.; Hewlett W. A.; Blakely R. D. Colocalization and regulated physical association of presynaptic serotonin transporters with A3 adenosine receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2011, 80, 458–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren T.; Grants I.; Alhaj M.; McKiernan M.; Jacobson M.; Hassanian H. H.; Frankel W.; Wunderlich J.; Christofi F. L. Impact of disrupting adenosine A3 receptors (A3–/–AR) on colonic motility or progression of colitis in the mouse. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2011, 17, 1698–1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson K. A.; Ji X.-D.; Li A. H.; Melman N.; Siddiqui M. A.; Shin K. J.; Marquez V. E.; Ravi R. G. Methanocarba analogues of purine nucleosides as potent and selective adenosine receptor agonists. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 2196–2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchilibon S.; Joshi B. V.; Kim S. K.; Duong H. T.; Gao Z. G.; Jacobson K. A. Methanocarba 2,N6-disubstituted adenine nucleosides as highly potent and selective A3 adenosine receptor agonists. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 1745–1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson K. A.; Siddiqi S. M.; Olah M. E.; Ji X. D.; Melman N.; Bellamkonda K.; Meshulam Y.; Stiles G. L.; Kim H. O. Structure-activity relationships of 9-alkyladenine and ribose-modified adenosine derivatives at rat A3 adenosine receptors. J. Med. Chem. 1995, 38, 1720–1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong L. S.; Pal S.; Choe S. A.; Choi W. J.; Jacobson K. A.; Gao Z. G.; Klutz A. M.; Hou X.; Kim H. O.; Lee H. W.; Lee S. K.; Tosh D. K.; Moon H. R. Structure activity relationships of truncated D- and L- 4′-thioadenosine derivatives as species-independent A3 adenosine receptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 6609–6613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melman A.; Wang B.; Joshi B. V.; Gao Z. G.; de Castro S.; Heller C. L.; Kim S. K.; Jeong L. S.; Jacobson K. A. Selective A3 adenosine receptor antagonists derived from nucleosides containing a bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane ring system. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 8546–8556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou X.; Majik M. S.; Kim K.; Pyee Y.; Lee Y.; Alexander V.; Chung H. J.; Lee H. W.; Chandra G.; Lee J. H.; Park S. G.; Choi W. J.; Kim H. O.; Phan K.; Gao Z. G.; Jacobson K. A.; Choi S.; Lee S. K.; Jeong L. S. Structure-activity relationships of truncated C2- or C8-substituted adenosine derivatives as dual acting A2A and A3 adenosine receptor ligands. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 342–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auchampach J. A.; Gizewski E.; Wan T. C.; de Castro S.; Brown G. G.; Jacobson K. A. Synthesis and pharmacological characterization of [125I]MRS5127, a high affinity, selective agonist radioligand for the A3 adenosine receptor. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010, 79, 967–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosh D. K.; Deflorian F.; Phan K.; Gao Z. G.; Wan T. C.; Gizewski E.; Auchampach J. A.; Jacobson K. A. Structure-guided design of A3 adenosine receptor-selective nucleosides: Combination of 2-arylethynyl and bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane substitutions. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 4847–4860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosh D. K.; Chinn M.; Ivanov A. A.; Klutz A. M.; Gao Z. G.; Jacobson K. A. Functionalized congeners of A3 adenosine receptor-selective nucleosides containing a bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane ring system. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 7580–7592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpini R.; Buccioni M.; Dal Ben D.; Lambertucci C.; Lammi C.; Marucci G.; Ramadori A. T.; Klotz K. N.; Cristalli G. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 2-alkynyl-N6-methyl-5′-N-methylcarboxamidoadenosine derivatives as potent and highly selective agonists for the human adenosine A3 receptor. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 7897–7900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinchilla R.; Nájera C. The Sonogashira reaction: A booming methodology in synthetic organic chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 874–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi W. J.; Park J. G.; Yoo S. J.; Kim H. P.; Moon H. R.; Chun M. W.; Jung Y. H.; Jeong L. S. Syntheses of D- and L-cyclopentenone derivatives using ring-closing metathesis: versatile intermediates for the synthesis of D- and L-carbocyclic nucleosides. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 6490–6494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi B. V.; Melman A.; Mackman R. L.; Jacobson K. A. Synthesis of ethyl (1S,2R,3S,4S,5S)-2,3-O-(isopropylidene)-4-hydroxy-bicyclo [3.1.0] hexane-carboxylate from L-ribose: A versatile chiral synthon for preparation of adenosine and P2 receptor ligands. Nucleosides, Nucleotides, Nucleic Acids 2008, 27, 279–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordstedt C.; Fredholm B. B. A modification of a protein-binding method for rapid quantification of cAMP in cell-culture supernatants and body fluid. Anal. Biochem. 1990, 189, 231–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeson P. D.; Springthorpe B. The influence of drug-like concepts on decision-making in medicinal chemistry. Nature Rev. Drug Discovery 2007, 6, 881–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z. G.; Verzijl D.; Zweemer A.; Ye K.; Göblyös A.; IJzerman A. P.; Jacobson K. A. Functionally biased modulation of A3 adenosine receptor agonist efficacy and potency by imidazoquinolinamine allosteric enhancers. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011, 82, 658–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.