Abstract

The adult mammalian intestine has long been used as a model to study adult stem cell function and tissue renewal as the intestinal epithelium is constantly undergoing self-renewal throughout adult life. This is accomplished through the proliferation and subsequent differentiation of the adult stem cells located in the crypt. The development of this self-renewal system is, however, poorly understood. A number of studies suggest that the formation/maturation of the adult intestine is conserved in vertebrates and depends on endogenous thyroid hormone (T3). In amphibians such as Xenopus laevis, the process takes place during metamorphosis, which is totally dependent upon T3 and resembles postembryonic development in mammals when T3 levels are also high. During metamorphosis, the larval epithelial cells in the tadpole intestine undergo apoptosis and concurrently, adult epithelial stem/progenitor cells are formed de novo, which subsequently lead to the formation of a trough-crest axis of the epithelial fold in the frog, resembling the crypt-villus axis in the adult mammalian intestine. Here we will review some recent molecular and genetic studies that support the conservation of the development of the adult intestinal stem cells in vertebrates. We will discuss the mechanisms by which T3 regulates this process via its nuclear receptors.

Keywords: adult organ-specific stem cell; histone methyltransferase; transcriptional coactivator; thyroid hormone receptor; dedifferentiation, Xenopus laevis, metamorphosis.

Introduction

Organ homeostasis and tissue repair is dependent upon organ-specific adult stem cells. When needed, the adult stem cells proliferate and their offspring subsequently differentiate to replace the cells lost physiologically or due to tissue damage. Because of the obvious potential medical applications, extensive studies have been carried out on the properties and functions of various adult stem cells. One of the best-studied models for adult stem cells is the vertebrate intestine. Throughout adult life, the intestinal epithelium, the tissue responsible for the main physiological function of the intestine, is constantly renewed. In mammals, the stem cells located in the crypts proliferate and their offspring then differentiate as they migrate up along the villus/crypt axis to replace the fully differentiated cells undergoing physiological apoptosis or programmed cell death near the tip of the villus. This allows the entire intestinal epithelium to be replaced once every 1-6 days 1-3. A similar self-renewing system exists in other vertebrates as well. In the case of metamorphosing amphibians such as Xenopus laevis, the epithelium is self-renewed every 2 weeks or so 4.

While extensive studies have been done to characterize the adult stem cells in the mammalian intestine 3, 5-7, there is only limited information on their formation during development. In mammals, the maturation of the intestine takes place around birth 6-9, a period termed post-embryonic development when plasma thyroid hormone (T3) concentrations are high 10. Interestingly, this postembryonic period resembles the T3-dependent amphibian metamorphosis 10 when the larval intestine transforms into the frog intestine in a process involving de novo formation of the intestinal stem cells 6, 8, 11. Here we will review some recent findings on the regulation of the adult intestinal stem cell formation by T3.

Adult stem cell formation during postembryonic development

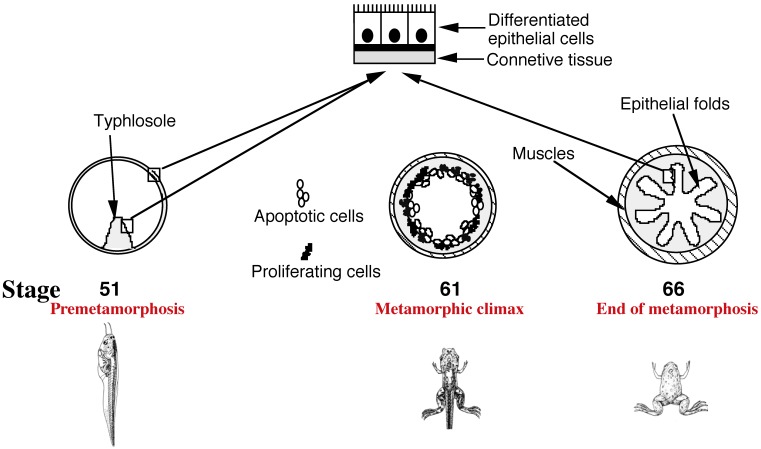

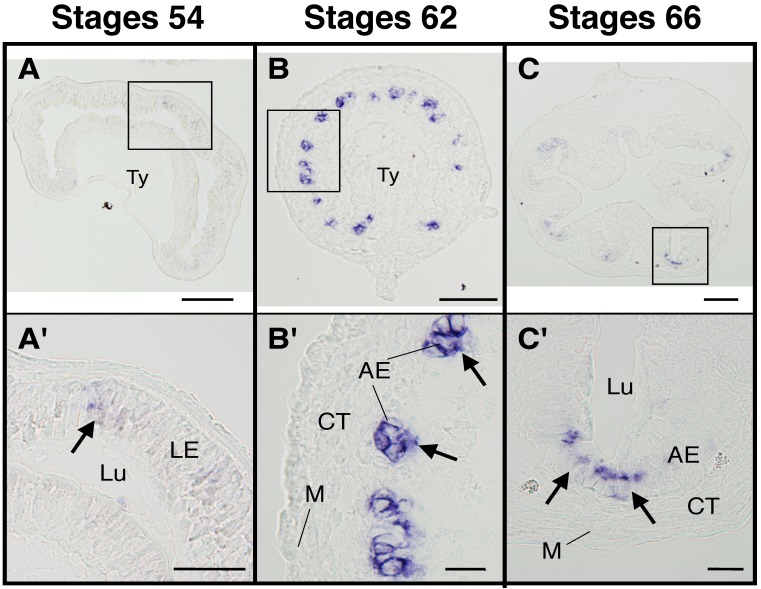

In mammals, a functional intestine is formed during embryogenesis. The intestine, however, undergoes extensive maturation around birth to form the adult intestine 6, 7, 9. During mouse embryogenesis, villus formation begins around embryonic day 14.5 (E14.5) but crypt formation and the establishment of the mature villus-crypt axis, where the adult stem cells are localized in the crypts, take place in the first 3 weeks after birth 6, 7, 9. In Xenopus laevis, arguably the best studied amphibian species, a functional intestine is formed at the end of embryogenesis in a feeding tadpole 11. The tadpole intestine has a much simpler structure than the frog intestine. In premetamorphic tadpoles, the intestine is made of mostly a single layer of larval epithelial cells, with little surrounding connective tissue and muscles except in the typhlosole, the single epithelial fold in the tadpole intestine 11 (Fig. 1). During metamorphosis, the larval epithelial cells undergo programmed cell death or apoptosis and concurrently, adult epithelial progenitor cells are formed de novo and rapidly proliferate 6, 8, 11-13. These cells express strongly the typical markers, such as LGR5 (Fig. 2) 14, which are expressed in the mammalian adult intestinal stem cells (and thus for simplicity, we will refer them as adult stem cells or progenitor cells interchangeably). Subsequently these cells differentiate to form a multiply folded adult epithelium with elaborate connective tissue and muscles (Fig. 1). While there is no further formation of the crypt-villus axis along the epithelial folds, the frog trough-crest axis of the epithelial folds formed by the end of metamorphosis, with the adult stem cells eventually restricted to the trough of the fold, resembles the crypt-villus axis in adult mammals.

Fig 1.

Intestinal remodeling during Xenopus laevis metamorphosis as a model to study adult organ-specific stem cell development in vertebrates. In premetamorphic tadpoles at stage 51, the intestine has only a single fold, the typhlosole, and is structurally similar to the mammalian embryonic intestine. At the metamorphic climax around stage 61, the larval epithelial cells begin to undergo apoptosis, as indicated by the open circles. Concurrently, the proliferating adult progenitor/stem cells are developed de novo from larval epithelial cells through dedifferentiation, as indicated by black dots. By the end of metamorphosis at stage 66, the newly differentiated adult epithelial cells form a multiply folded epithelium, similar to mammalian adult intestines.

Fig 2.

The adult intestinal stem cell marker gene LGR5 is upregulated at the climax of intestinal metamorphosis. Cross-sections of the intestine at premetamorphic stage 54 (A, A'), metamorphic climax stage 62 (B, B'), and the end of metamorphosis (stage 66) (C, C') were analyzed by in situ hybridization for LGR5 expression. Arrows indicate the cells expressing LGR5 (A'-C'). Higher magnification of boxed areas in (A)-(C) are shown in (A')-(C'). AE: adult epithelial progenitor/stem cells, CT: connective tissue, LE: larval epithelial cell, Lu: lumen, M: muscle layer, Ty: typhlosole. Scale bars are 100 µm (A-C) and 20 µm (A'-C'), respectively. Based on 14.

T3 regulation of adult intestinal stem cell formation

T3 has long been known to be essential and sufficient for frog metamorphosis 15, 16. In premetamorphic tadpoles, there is little T3. The endogenous T3 becomes detectable around stage 55 in Xenopus laevis, the onset of metamorphosis. As metamorphosis proceeds, the plasma T3 rises to a peak level around stage 62, the climax of metamorphosis. By the end of metamorphosis as tail resorption completes, plasma T3 is reduced to much lower levels 17. Importantly, while different organs undergo vastly different changes, including total resorption of the tail at the end of metamorphosis, de novo formation of the limbs early during metamorphosis, all metamorphic events are controlled by T3. Blocking the synthesis of endogenous T3 leads to metamorphosis inhibition and the formation of giant tadpoles while addition of exogenous, physiological levels of T3 induces precocious metamorphosis in premetamorphic tadpoles. More importantly, the effect of T3 on different organs appear to be organ autonomous since cultures of different organs such as tail, limb, and intestine, from premetamorphic tadpoles can be induced to metamorphose with the addition of T3 to the medium 15, 16. When Xenopus laevis tadpole intestine is cultured with T3, both larval cell death and adult epithelium development are induced, indicating not only that T3 controls the formation of the adult intestinal stem cells but also that the stem cells are originated from the larval intestine.

To determine the origin of the adult stem/progenitor cells, we have recently made use of the ability to induce intestinal metamorphosis in organ cultures with T3 treatment and the existence of a transgenic frog line expressing GFP ubiquitously. We isolated intestine from premetamorphic transgenic tadpoles as well as wild type siblings and separated the epithelium from the rest of the intestine (the non-epithelium). We recombined epithelium derived from wild type or GFP-expressing transgenic tadpoles with the non-epithelium from either wild type or GFP-expressing transgenic tadpoles. We treated the cultures with T3 to induce metamorphosis, leading to the formation of adult progenitor/stem cells after 5 days and eventually adult epithelium after longer treatment. We showed that GFP-labeled adult stem cells and GFP-labeled differentiated adult epithelium were formed only when the epithelium used for the recombinant organ cultures was derived from transgenic tadpoles expressing GFP 12, indicating that the intestinal progenitor/stem cells originate from the larval epithelium, likely through T3-induced dedifferentiation of some larval epithelial cells.

Similarly, T3 appears to play a critical role in the development of mammalian adult intestinal stem cells. As indicated above, intestinal maturation occurs around birth in mammals when plasma T3 levels are high, just like during amphibian metamorphosis. In mouse, this corresponds to the first 3 weeks after birth with plasma T3 level peaks around 2 weeks after birth 18. T3 or T3 receptor (TR, see below) deficiency leads to reduction in the number of epithelial cells along the crypt-villus axis and abnormal intestinal morphology 19-23, arguing that proper T3 signaling is important for adult stem cell formation.

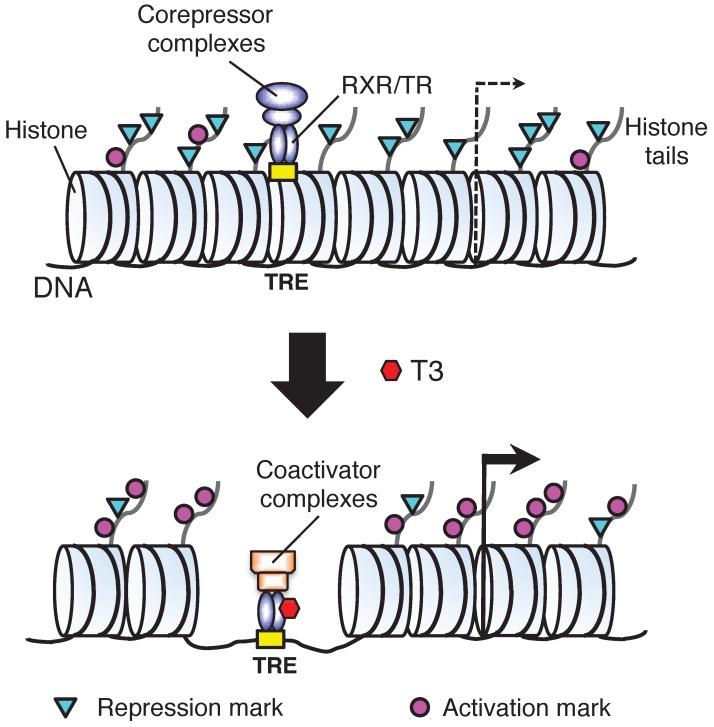

Mechanism of gene regulation by T3

T3 functions mainly by regulating gene expression via its nuclear receptors or TRs. T3 can both activate and repress target gene expression. Most studies on T3 have been on genes induced by T3. In vitro and in vivo studies by using reporter genes have shown that TRs mainly function as heterodimers with 9-cis retinoic acid receptors (RXRs) to bind to T3 response element (TRE) in T3 inducible target genes 24-27. In the absence of T3, TR/RXR represses target genes by recruiting corepressor complexes that contain histone deacetylases while when T3 is present, liganded TR/RXR recruits coactivator complexes containing various histone modification enzymes and chromatin remodeling proteins to alter local chromatin and activate transcription 25, 28-36. Importantly, we and others have shown that during Xenopus laevis development, unliganded TR/RXR binds to target genes in premetamorphic tadpoles and recruits corepressor complexes, which are important to regulate the timing of metamorphosis 36-39. On the other hand, liganded TR is required to recruit coactivators to the endogenous target genes during metamorphosis to activate their expression and induce metamorphosis 36, 40-53.

A number of studies have shown that the T3-dependent recruitment of various cofactor complexes correlates with local histone modifications, particularly acetylation and methylations, and gene regulation at target genes during metamorphosis 36-39, 47, 49-56. In addition to histone modifications, gene activation by liganded TR in the frog oocyte transcription system, where the DNA is chromatinized, also leads to chromatin disruption 57-59, resulting in a loss of up to 3 nucleosomes per receptor binding locus 58. Such nucleosome removal by liganded TR may be mediated by the recruit chromatin remodeling complexes containing Brg1 and BAF57 to the TRE of the reporter gene 60, 61. Interestingly, both Brg1 and BAF57 are expressed during intestinal metamorphosis in Xenopus laevis 61, suggesting that similar nucleosome removal occurs during intestinal metamorphosis. Indeed, we have recently shown that in Xenopus tropicalis, a species highly related to Xenopus laevis, gene activation by T3 causes the loss of core histones at TR target genes both during natural and T3-induced intestinal remodeling 55. Thus, T3 regulates target gene transcription during intestinal stem cell development via both histone modifications and nucleosomal removal to facilitate the recruitment of transcriptional machinery (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

A model for gene regulation by TR. T3 functions by regulating gene transcription through T3 receptors (TRs). In the absence of T3 (as in premetamorphic tadpole), TR forms heterodimers with RXR (9-cis retinoic acid receptor) and the heterodimer binds to the T3 response elements (TREs) in the target genes to repress their expression by recruiting corepressor complexes containing histone deacetylases. When T3 is present, the corepressor complexes are released and the liganded TR/RXR recruits coactivator complexes containing histone acetyltransferases and histone methyltransferases such as PRMT1 (protein arginine methyltransferase 1). The coactivator complexes will modify histones or cause the removal of nucleosomes, leading to the activation of gene expression. Based on 55.

Gene regulation during adult stem cell development

The total dependence on T3 of intestinal metamorphosis in amphibians offers a means to identify genes likely involved in adult stem cell development. We and others have previously isolated genes that are regulated by T3 in the intestine of Xenopus laevis 62-66. In particular, genome-wide microarray studies have identified many genes and signaling pathways whose regulation correlates with stem cell development and larval cell death during intestinal metamorphosis 63, 65. Interestingly, a comparative study found that among the genes that are highly upregulated in the intestine (7 fold or more) at the climax of metamorphosis (stage 61) compared to pre- or end of metamorphosis, most of the homologous genes in mouse (19 out of 27 analyzed) have their peak levels of expression in the intestine within the first 2 weeks after birth 65, when the mouse intestine matures into the adult form. These findings suggest that similar T3-dependent gene regulation programs function in the formation of the adult intestinal stem cells in both amphibians and mammals.

Among the genes upregulated during intestinal metamorphosis is protein arginine methyltransferase 1 (PRMT1) 49, 67, which functions as TR-coactivator. PRMT1 is highly expressed in the adult progenitor/stem cells but not in larval or adult differentiated epithelial cells 68. Transgenic overexpression of PRMT1 leads to increased adult progenitor/stem cells, while knocking down the endogenous PRMT1 expression reduces these cells, arguing that PRMT1 is important for the formation and/or proliferation of the adult progenitor and/or stem cells 68.

Interestingly, when PRMT1 expression was analyzed during mouse and zebrafish development, a similar spatiotemporal pattern was observed 68. That is, little PRMT1 expression was detected in the larval/neonatal intestine in zebrafish or mouse when plasma T3 levels were low. During the transition to the adult intestine when T3 levels were high, PRMT1 was upregulated in the presumptive developing adult stem cells. These findings suggest that the embryonic/neonatal mouse or zebrafish intestinal stem cells are molecularly distinct from those in the adult intestine and that the formation of the adult intestinal stem cells may utilize conserved mechanisms, such as the dependence on T3 and involvement of PRMT1, during vertebrate development. PRMT1 upregulation thus represents the first reported molecular events during mouse or zebrafish adult stem cell development.

Two recent studies in mouse have provided further evidence that mouse adult intestinal stem cells are distinct from the embryonic/neonatal epithelial or stem cells. Harper et al. 9 and Muncan et al. 69 studied the transcriptional repressor, B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein 1 (Blimp1) during mouse development by using knockout animals. Blimp1 is strongly expressed throughout the intestinal epithelium of embryonic and newborn mice. Shortly after birth as the intestine matures into the adult form, Blimp1 expression is down-regulated in the intervillus pockets where crypts begin to develop, while its expression in the rest of the epithelium cells persists. As the crypts develop, all cells in the newly formed crypts lack Blimp1 expression. Subsequently, the epithelial cells in the villus gradually loses Blimp1 expression, first at the bottom and then toward the tip of the villus, likely due to the replacement of the neonatal epithelial cells by the newly differentiated epithelial cells derived from the crypt cells lacking Blimp1 expression that are migrating toward the tip of the villus. Eventually, in the adult intestine, Blimp1 expression is absent throughout the epithelium. Thus, the loss of Blimp1 expression in the developing crypt is likely one of the early events for the embryonic/neonatal epithelial cells to develop into the adult stem cells, whose offspring subsequently populate the epithelium in the adult intestine. Consistently and more importantly, intestinal epithelium-specific knockout of Blimp1 causes fetal intestinal epithelium to adopt the adult epithelium fate, indicating that Blimp1 functions to delay maturation of the intestinal epithelium. Thus, like in amphibians, the adult stem cells are distinct from the embryonic/neonatal stem cells but are derived from the immature fetal epithelial cells.

Conclusion

Adult organ-specific stem cells have attracted a great deal of attention due to their potential application in tissue replacement therapies. The constant self-renewal of the intestinal epithelium has made intestinal stem cells an excellent model to study stem cell property and function. Studies on intestinal metamorphosis in amphibians and intestinal maturation in mouse have shown that the adult stem cells of the intestine are distinct from the larval/neonatal intestinal epithelial (stem) cells and that they are formed during postembryonic development in a T3 dependent manner. Furthermore, many genes are similarly regulated during the development of the adult intestinal stem cells in mouse and Xenopus laevis. In particular, PRMT1 has been shown to be important for adult intestinal stem cell development in Xenopus laevis while Blimp1 is important for delaying the formation of the adult intestine in mouse, a process important for neonatal survival of the animal 9, 69. These findings raise many interesting questions for future studies. One obvious question is whether the downregulation of Blimp1 and upregulation of PRMT1 in the intestine during mouse postembryonic development are also regulated by T3. What is the relationship, if any, between Blimp 1 downregulation and PRMT1 upregulation? Conversely, the regulation and function of Blimp1 gene during amphibian metamorphosis will also be a subject of future research. Additionally, stem cell formation and survival also depend on the presence of proper stem cell niche. The nature and function of such niche during adult intestinal stem cell development remain to be investigated. Interestingly, our recent recombinant organ culture studies with transgenic animals expressing a constitutively active TR suggest that T3 induces the larval/tadpole epithelium to undergo cell-autonomous formation of adult progenitor cells and also induces the non-epithelial tissues, most likely the connective tissue, to form or contribute to the establishment of the adult stem cell niche 70. The actions of T3 in both the epithelium and non-epithelium are required for the formation of true adult stem cells expressing the adult intestinal stem cell markers and eventually the adult epithelium. It is tempting to speculate the during mammalian postembryonic development, T3 also induces the non-epithelium to help the formation of adult stem cell niche for the transformation of the Blimp1 positive embryonic/neonatal cells to Blimp1 negative adult intestinal stem cells. Identifying the genes and factors induced by T3 in the non-epithelium is clearly important toward understanding the nature of the stem cell niche and the mechanism of stem cell development during vertebrate development.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China No.30870113 and the Intramural Research Program of NICHD, NIH.

References

- 1.MacDonald WC, Trier JS, Everett NB. Cell proliferation and migration in the stomach, duodenum, and rectum of man: Radioautographic studies. Gastroenterology. 1964;46:405–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toner PG, Carr KE, Wyburn GM. The Digestive System: An Ultrastructural Atlas and Review. London: Butterworth; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Flier LG, Clevers H. Stem Cells, Self-Renewal, and Differentiation in the Intestinal Epithelium. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:241–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McAvoy JW, Dixon KE. Cell proliferation and renewal in the small intestinal epithelium of metamorphosing and adult Xenopus laevis. J Exp Zool. 1977;202:129–138. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sancho E, Eduard Batlle E, Clevers H. Signaling pathways in intestinal development and cancer. Annu Rev Cell DevBiol. 2004;20:695–723. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.092805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishizuya-Oka A, Shi YB. Evolutionary insights into postembryonic development of adult intestinal stem cells. Cell Biosci. 2011;1:37. doi: 10.1186/2045-3701-1-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crosnier C, Stamataki D, Lewis J. Organizing cell renewal in the intestine: stem cells, signals and combinatorial control. NATURE REVIEWS | GENETICS. 2006;7:349–359. doi: 10.1038/nrg1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi YB, Hasebe T, Fu L, Fujimoto K, Ishizuya-Oka A. The development of the adult intestinal stem cells: Insights from studies on thyroid hormone-dependent amphibian metamorphosis. Cell Biosci. 2011;1:30. doi: 10.1186/2045-3701-1-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harper J, Mould A, Andrews RM, Bikoff EK, Robertson EJ. The transcriptional repressor Blimp1/Prdm1 regulates postnatal reprogramming of intestinal enterocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:10585–10590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105852108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tata JR. Gene expression during metamorphosis: an ideal model for post-embryonic development. Bioessays. 1993;15:239–248. doi: 10.1002/bies.950150404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi Y-B, Ishizuya-Oka A. Biphasic intestinal development in amphibians: Embryogensis and remodeling during metamorphosis. Current Topics in Develop Biol. 1996;32:205–235. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60429-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishizuya-Oka A, Hasebe T, Buchholz DR, Kajita M, Fu L, Shi YB. Origin of the adult intestinal stem cells induced by thyroid hormone in Xenopus laevis. Faseb J. 2009;23:2568–2575. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-128124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schreiber AM, Cai L, Brown DD. Remodeling of the intestine during metamorphosis of Xenopus laevis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3720–3725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409868102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun G, Hasebe T, Fujimoto K, Lu R, Fu L, Matsuda H, Kajita M, Ishizuya-Oka A, Shi YB. Spatio-temporal expression profile of stem cell-associated gene LGR5 in the intestine during thyroid hormone-dependent metamorphosis in Xenopus laevis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilbert LI, Tata JR, Atkinson BG. Metamorphosis: Post-embryonic reprogramming of gene expression in amphibian and insect cells. New York: Academic Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi Y-B. Amphibian Metamorphosis: From morphology to molecular biology. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leloup J, Buscaglia M. La triiodothyronine: hormone de la métamorphose des amphibiens. CR Acad Sci. 1977;284:2261–2263. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedrichsen S, Christ S, Heuer H, Schäfer MKH, Mansouri A, Bauer K, Visser TJ. Regulation of iodothyronine deiodinases in the Pax8-/- mouse model of congenital hypothyroidism. Endocrinology. 2003;144:777–784. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plateroti M, Gauthier K, Domon-Dell C, Freund JN, Samarut J, Chassande O. Functional interference between thyroid hormone receptor alpha (TRalpha) and natural truncated TRDeltaalpha isoforms in the control of intestine development. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4761–4772. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.14.4761-4772.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flamant F, Poguet AL, Plateroti M, Chassande O, Gauthier K, Streichenberger N, Mansouri A, Samarut J. Congenital hypothyroid Pax8(-/-) mutant mice can be rescued by inactivating the TRalpha gene. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:24–32. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.1.0766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kress E, Rezza A, Nadjar J, Samarut J, Plateroti M. The frizzled-related sFRP2 gene is a target of thyroid hormone receptor alpha1 and activates beta-catenin signaling in mouse intestine. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1234–1241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806548200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plateroti M, Chassande O, Fraichard A, Gauthier K, Freund JN, Samarut J, Kedinger M. Involvement of T3Ralpha- and beta-receptor subtypes in mediation of T3 functions during postnatal murine intestinal development. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1367–1378. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70501-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plateroti M, Kress E, Mori JI, Samarut J. Thyroid hormone receptor alpha1 directly controls transcription of the beta-catenin gene in intestinal epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3204–3214. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.8.3204-3214.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lazar MA. Thyroid hormone receptors: multiple forms, multiple possibilities. Endocr Rev. 1993;14:184–193. doi: 10.1210/edrv-14-2-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yen PM. Physiological and molecular basis of thyroid hormone action. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1097–1142. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, Herrlich P, Schutz G, Umesono K, Blumberg B, Kastner P, Mark M, Chambon P. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83:835–839. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Ann Rev Biochem. 1994;63:451–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ito M, Roeder RG. The TRAP/SMCC/Mediator complex and thyroid hormone receptor function. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2001;12:127–134. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rachez C, Freedman LP. Mechanisms of gene regulation by vitamin D(3) receptor: a network of coactivator interactions. Gene. 2000;246:9–21. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J, Lazar MA. The mechanism of action of thyroid hormones. Annu Rev Physiol. 2000;62:439–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.62.1.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burke LJ, Baniahmad A. Co-repressors 2000. FASEB J. 2000;14:1876–1888. doi: 10.1096/fj.99-0943rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jepsen K, Rosenfeld MG. Biological roles and mechanistic actions of co-repressor complexes. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:689–698. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.4.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones PL, Shi Y-B. N-CoR-HDAC corepressor complexes: Roles in transcriptional regulation by nuclear hormone receptors. In: Workman JL, editor. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology: Protein Complexes that Modify Chromatin; Volume 274. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2003. pp. 237–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rachez C, Freedman LP. Mediator complexes and transcription. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:274–280. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu X, Lazar MA. Transcriptional Repression by Nuclear Hormone Receptors. TEM. 2000;11(1):6–10. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(99)00215-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi Y-B. Dual functions of thyroid hormone receptors in vertebrate development: the roles of histone-modifying cofactor complexes. Thyroid. 2009;19:987–999. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomita A, Buchholz DR, Shi Y-B. Recruitment of N-CoR/SMRT-TBLR1 corepressor complex by unliganded thyroid hormone receptor for gene repression during frog development. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3337–3346. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.8.3337-3346.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sachs LM, Jones PL, Havis E, Rouse N, Demeneix BA, Shi Y-B. N-CoR recruitment by unliganded thyroid hormone receptor in gene repression during Xenopus laevis development. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:8527–8538. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.24.8527-8538.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sato Y, Buchholz DR, Paul BD, Shi Y-B. A role of unliganded thyroid hormone receptor in postembryonic development in Xenopus laevis. Mechanisms of Development. 2007;124:476–488. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schreiber AM, Das B, Huang H, Marsh-Armstrong N, Brown DD. Diverse developmental programs of Xenopus laevis metamorphosis are inhibited by a dominant negative thyroid hormone receptor. PNAS. 2001;98:10739–10744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191361698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown DD, Cai L. Amphibian metamorphosis. Dev Biol. 2007;306:20–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buchholz DR, Hsia VS-C, Fu L, Shi Y-B. A dominant negative thyroid hormone receptor blocks amphibian metamorphosis by retaining corepressors at target genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6750–6758. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.19.6750-6758.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buchholz DR, Tomita A, Fu L, Paul BD, Shi Y-B. Transgenic analysis reveals that thyroid hormone receptor is sufficient to mediate the thyroid hormone signal in frog metamorphosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9026–9037. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.20.9026-9037.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buchholz DR, Paul BD, Fu L, Shi YB. Molecular and developmental analyses of thyroid hormone receptor function in Xenopus laevis, the African clawed frog. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2006;145:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakajima K, Yaoita Y. Dual mechanisms governing muscle cell death in tadpole tail during amphibian metamorphosis. Dev Dyn. 2003;227:246–255. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Denver RJ, Hu F, Scanlan TS, Furlow JD. Thyroid hormone receptor subtype specificity for hormone-dependent neurogenesis in Xenopus laevis. Dev Biol. 2009;326:155–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bagamasbad P, Howdeshell KL, Sachs LM, Demeneix BA, Denver RJ. A role for basic transcription element-binding protein 1 (BTEB1) in the autoinduction of thyroid hormone receptor beta. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2275–2285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709306200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schreiber AM, Mukhi S, Brown DD. Cell-cell interactions during remodeling of the intestine at metamorphosis in Xenopus laevis. Dev Biol. 2009;331:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsuda H, Paul BD, Choi CY, Hasebe T, Shi Y-B. Novel functions of protein arginine methyltransferase 1 in thyroid hormone receptor-mediated transcription and in the regulation of metamorphic rate in Xenopus laevis. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:745–757. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00827-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paul BD, Buchholz DR, Fu L, Shi Y-B. Tissue- and gene-specific recruitment of steroid receptor coactivator-3 by thyroid hormone receptor during development. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:27165–27172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503999200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paul BD, Fu L, Buchholz DR, Shi Y-B. Coactivator recruitment is essential for liganded thyroid hormone receptor to initiate amphibian metamorphosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5712–5724. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5712-5724.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paul BD, Buchholz DR, Fu L, Shi Y-B. SRC-p300 coactivator complex is required for thyroid hormone induced amphibian metamorphosis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7472–7481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607589200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Havis E, Sachs LM, Demeneix BA. Metamorphic T3-response genes have specific co-regulator requirements. EMBO Reports. 2003;4:883– 888. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bilesimo P, Jolivet P, Alfama G, Buisine N, Le Mevel S, Havis E, Demeneix BA, Sachs LM. Specific Histone Lysine 4 Methylation Patterns Define TR-Binding Capacity and Differentiate Direct T3 Responses. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:225–237. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matsuura K, Fujimoto K, Fu L, Shi Y-B. Liganded thyroid hormone receptor induces nucleosome removal and histone modifications to activate transcription during larval intestinal cell death and adult stem cell development. Endocrinology. 2012;153:961–972. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matsuura K, Fujimoto K, Das B, Fu L, Lu CD, Shi YB. Histone H3K79 methyltransferase Dot1L is directly activated by thyroid hormone receptor during Xenopus metamorphosis. Cell Biosci. 2012;2:25. doi: 10.1186/2045-3701-2-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wong J, Shi YB, Wolffe AP. A role for nucleosome assembly in both silencing and activation of the Xenopus TR beta A gene by the thyroid hormone receptor. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2696–2711. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.21.2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wong J, Shi Y-B, Wolffe AP. Determinants of chromatin disruption and transcriptional regulation instigated by the thyroid hormone receptor: hormone-regulated chromatin disruption is not sufficient for transcriptinal activation. EMBO J. 1997;16:3158–3171. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hsia SC, Shi YB. Chromatin disruption and histone acetylation in regulation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat by thyroid hormone receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:4043–4052. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.12.4043-4052.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang Z-Q, Li J, Sachs LM, Cole PA, Wong J. A role for cofactor-cofactor and cofactor-histone interactions in targeting p300, SWI/SNF and Mediator for transcription. EMBO J. 2003;22:2146–2155. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heimeier RA, Hsia VS-C, Shi Y-B. Participation of BAF57 and BRG1-Containing Chromatin Remodeling Complexes in Thyroid Hormone-Dependent Gene Activation during Vertebrate Development. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:1065–1077. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shi Y-B, Brown DD. The earliest changes in gene expression in tadpole intestine induced by thyroid hormone. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:20312–20317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buchholz DR, Heimeier RA, Das B, Washington T, Shi Y-B. Pairing morphology with gene expression in thyroid hormone-induced intestinal remodeling and identification of a core set of TH-induced genes across tadpole tissues. Dev Biol. 2007;303:576–590. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heimeier RA, Das B, Buchholz DR, Shi YB. The xenoestrogen bisphenol A inhibits postembryonic vertebrate development by antagonizing gene regulation by thyroid hormone. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2964–2973. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heimeier RA, Das B, Buchholz DR, Fiorentino M, Shi YB. Studies on Xenopus laevis intestine reveal biological pathways underlying vertebrate gut adaptation from embryo to adult. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R55. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-5-r55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Amano T, Yoshizato K. Isolation of genes involved in intestinal remodeling during anuran metamorphosis. Wound Repair Regen. 1998;6:302–313. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.1998.60406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fujimoto K, Matsuura K, Hu-Wang E, Lu R, Shi YB. Thyroid Hormone Activates Protein Arginine Methyltransferase 1 Expression by Directly Inducing c-Myc Transcription during Xenopus Intestinal Stem Cell Development. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:10039–10050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.335661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Matsuda H, Shi YB. An essential and evolutionarily conserved role of protein arginine methyltransferase 1 for adult intestinal stem cells during postembryonic development. Stem Cells. 2010;28:2073–2083. doi: 10.1002/stem.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Muncan V, Heijmans J, Krasinski SD, Buller NV, Wildenberg ME, Meisner S, Radonjic M, Stapleton KA, Lamers WH, Biemond I. et al. Blimp1 regulates the transition of neonatal to adult intestinal epithelium. Nat Commun. 2011;2:452. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hasebe T, Buchholz DR, Shi YB, Ishizuya-Oka A. Epithelial-connective tissue interactions induced by thyroid hormone receptor are essential for adult stem cell development in the Xenopus laevis intestine. Stem Cells. 2011;29:154–161. doi: 10.1002/stem.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]