Abstract

Ebolavirus, a member of the family Filoviridae, causes high lethality in humans and nonhuman primates. Research focused on protection and therapy for Ebola virus infection has investigated the potential role of antibodies. Recent evidence suggests that antibodies can be effective in protection from lethal challenge with Ebola virus in nonhuman primates. However, despite these encouraging results, studies have not yet determined the optimal antibodies and composition of an antibody cocktail, if required, which might serve as a highly effective and efficient prophylactic. To better understand optimal antibodies and their targets, which might be important for protection from Ebola virus infection, we sought to determine the profile of viral protein-specific antibodies generated during a natural cycle of infection in humans. To this end, we characterized the profile of antibodies against individual viral proteins of Sudan Ebola virus (Gulu) in human survivors and nonsurvivors of the outbreak in Gulu, Uganda, in 2000-2001. We developed a unique chemiluminescence enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for this purpose based on the full-length recombinant viral proteins NP, VP30, and VP40 and two recombinant forms of the viral glycoprotein (GP1-294 and GP1-649) of Sudan Ebola virus (Gulu). Screening results revealed that the greatest immunoreactivity was directed to the viral proteins NP and GP1-649, followed by VP40. Comparison of positive immunoreactivity between the viral proteins NP, GP1-649, and VP40 demonstrated a high correlation of immunoreactivity between these viral proteins, which is also linked with survival. Overall, our studies of the profile of immunorecognition of antibodies against four viral proteins of Sudan Ebola virus in human survivors may facilitate development of effective monoclonal antibody cocktails in the future.

INTRODUCTION

Ebolavirus, a member of the family Filoviridae, is the cause of Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF) (17, 28). The single-strand, negative-sense RNA genome encodes seven proteins (36), four of which, i.e., the nucleoprotein (NP), VP35, VP30, and the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L), are necessary for replication and transcription of viral RNA (vRNA) (26). The glycoprotein (GP) is responsible for viral entry, and the viral proteins VP40 and VP24 are responsible for assembly and release of the virion (39).

Many studies have investigated the role of humoral immunity and specific antibody recognition of different viral proteins of Ebola virus to identify antibodies that might protect from EHF and play a role in recovery (1, 8, 25). It has been observed in individuals infected with Ebola virus that adaptive immunity and several cytokine markers of early innate responses were lacking in those that ultimately succumbed to infection (2, 3, 21). Thus, in most fatal cases, patients fail to produce significant antibodies against the virus and die with persistently high viremia (15, 35, 40). Other studies, which focused on serosurveillance of individuals in regions where outbreaks previously occurred, suggested that the majority of antibodies directed against Ebola virus primarily targeted the viral proteins NP, VP40, and GP of the virus (12, 19, 22). However, these studies did not use sera from infected individuals during an outbreak.

The present study was initiated to understand the profile of the adaptive humoral immune response to individual viral proteins of Sudan Ebola virus (Gulu) (SUDV-gul) during the course of infection in human survivors, which would facilitate identification of specific epitope targets that might be useful for therapy. To this end, a serum database using samples obtained during the outbreak in Gulu, Uganda, in 2000-2001 and a eukaryotic cell-based expression system of full-length recombinant proteins for six of the seven genes of SUDV-gul were established. Additionally, two truncations of the viral glycoprotein (GP), GP1–294 and GP1–649, were recombinantly produced. The individual viral proteins were used as targets after initial screening by Western blot (WB) assay for detection of specific IgG in serum samples from human SUDV-gul patients at different times after infection.

A novel chemiluminescence enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was developed for these studies based on select recombinant viral proteins of SUDV-gul. It was validated and verified using control positive sera, along with 100 negative-control serum samples from Ugandans never diagnosed with EHF, to establish suitable cutoff values. Serum was screened against the recombinant viral proteins (NP, VP40, VP30, GP1–294, and GP1–649) of SUDV-gul using this technique. The results revealed that the greatest immunoreactivity was directed to NP and GP1–649, with a high correlation of immunoreactivity to both of these viral proteins. Furthermore, the success demonstrated using this ELISA indicates the potential utility of recombinant protein-based assays for diagnostics and surveillance of Ebola virus infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell line and antibodies.

A human embryonic kidney epithelial cell line, 293T, was cultured in RPMI 1640 (product R 8758; Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FCS) (HyClone, Logan, UT), 50 μg/ml of penicillin, 50 μg/ml of streptomycin, and 2 mM l-glutamine at 37°C in 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. An anti-FLAG murine monoclonal antibody was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (product F1804) and was used as a positive control for the detection of the recombinant viral protein during Western blot (WB) assays.

Ag and control Ag.

Total 293T cell lysate extract expressing a given recombinant viral protein of SUDV-gul was used as an antigen (Ag) during Western blot assays and ELISA. The construction of the recombinant viral proteins is described below. Cell lysates not expressing the viral recombinant protein were used as control antigens. Inactivated SUDV complete antigen was used as an additional antigen control. Inactivation of cell lysates prepared from cells infected with SUDV was performed by addition of 1% (wt/vol) SDS and then boiling for 10 min under biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) laboratory conditions. Following this procedure, cell lysates were then transferred to a fresh tube and moved to a BSL-2 laboratory, followed by boiling for an additional 10 min. For recombinant GP1–649, a purified (His-tagged) viral GP1–649 polypeptide (residues 1 to 649) of SUDV was prepared by expression in eukaryotic cells and purification by affinity chromatography by the Protein Expression Laboratory, Advanced Technology Program, SAIC-Frederick, Inc., Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research (FNL).

Sera. (i) Internal control sera.

A positive control for ELISA was obtained by pooling sera from five human survivors of SUDV-gul, obtained during the 2000-2001 outbreak in Uganda, which had previously tested positive for IgG to SUDV. A goat anti-SUDV serum, a second positive control in Western blot (WB) assays and ELISA, was produced at the Institute of Virology, Philipps-University Marburg, Marburg, Germany. To prepare this sera, SUDV virus was grown and purified under BSL-4 conditions and inactivated by gamma irradiation. The inactivated material was then injected into goats for production of anti-SUDV sera. The negative control was a pool of 10 serum samples collected from healthy volunteers in Uganda during 2003, which had no known exposure to filoviruses. An anti-FLAG murine monoclonal antibody (Stratagene) was used as an additional control in the WB and ELISAs. The positive control for the detection of SUDV GP1-649 by ELISA included two murine monoclonal antibodies, 3C10 and 17F6, that target the SUDV GP specifically (7).

(ii) Human sera.

A total of 178 serum samples, obtained from patients during the SUDV-gul outbreak in 2000-2001 in Uganda, were catalogued with relevant diagnostic data that were obtained during the outbreak. Serum samples were collected from survivors and victims of the disease and from patients that had not been infected with the virus. All serum samples used in this study were gamma irradiated.

Construction of plasmid cDNA clones of Ebola virus Sudan (Gulu) genes.

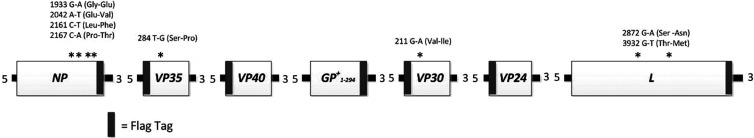

Using standard cloning techniques, the genes of SUDV-gul were cloned. Briefly, the genomic RNA of SUDV-gul was obtained by extraction of total RNA from virally infected Vero cells under BSL-4 conditions. This RNA was subsequently used as a template for reverse transcription (RT), followed by second-strand cDNA synthesis by PCR using specific primers that were designed from the published sequence of the SUDV-gul genome (primer sequences are available on request) (36) (GenBank accession no. AY729654). Five of the seven wild-type genes of the virus were cloned entirely as one fragment from the viral RNA, whereas the viral polymerase gene (L) was cloned out on two DNA fragments and reconstructed. The transmembrane form of the GP gene of SUDV-gul was previously cloned (kindly provided by Heinz Feldmann), and a subclone was created of the ectodomain of GP (GP1–294). Following cloning of the complete set of SUDV-gul wild-type genes, a subcloning was performed to generate full-length recombinant tagged genes containing the short 8-amino-acid peptide Flag Marker (N-DYKDDDDK-C). These tagged wild-type genes were then inserted into the backbone of a pCAGGS expression vector. Nucleotide sequence analysis of all of the tagged subcloned genes was performed, and results were compared to the complete SUDV-gul sequence that had been previously published (36) (GenBank accession no. AY729654). The nucleotide and amino acid changes that we found in our clones compared to the sequences previously published are depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig 1.

Overview of SUDV-gul recombinant gene construction. All cloned recombinant genes were sequenced and compared to the previously published sequence of SUDV-gul. For each gene, the locations of the Flag tag, along with the positions of nucleotide variations in the cloned genes compared to the published sequence, are indicated. The location of each nucleotide variation in the viral genes is indicated by a star, along with the corresponding nucleotide and amino acid changes. All changes observed in the cloned genes were detected in the viral RNA and reflect variations in viral RNA that was obtained from a different isolate for this study.

Transfection and antigen preparation.

Monolayers of 293T cells in 6-well dishes (35-mm wells), at 70% confluence, were individually transfected, using the GeneJuice transfection reagent, (Novagen 70967), according to the manufacturer's instructions, with a pCAGGS vector coding for a given recombinant viral protein. The procedure included the following; 100 μl of medium without serum was mixed with 3 μl of transfection reagent and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Following this initial incubation, 1 μg of a given pCAGGS-based construct was added to the mix and incubated again for 10 min. Next, 100 μl of the mixture was carefully added to the medium that overlaid the cell monolayer and left at 37°C for 48 h. Following incubation, cells were washed twice with chilled phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and 150 μl of radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer plus protease inhibitor (PI) (Roche Diagnostics GmbH 11245220) mix (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1% NP-40, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 1 mM NaF, 10 mM sodium β-glycerophosphate, 150 mM NaCl, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 1 μM aprotonin, 1 μM leupeptin, 1 μM pepstatin [Sigma-Aldrich, Israel]) was subsequently overlaid on the cells. Cells were then collected with a cell scraper, placed in 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes, and kept on ice for 30 min. The cell mix was then passed through a needle syringe 5 to 10 times and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The upper-layer fractions were collected, placed in new 1.5-ml tubes, and kept at −20°C until further use.

WB analysis.

As a preliminary step, 293T cell lysates containing the recombinant SUDV-gul proteins were assayed for total protein concentration using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein analysis kit (23225; Pierce). Typically, a 50-μl volume containing cell lysate of one or two individual viral proteins was loaded per lane on the Western blot, which was normalized to 40 μg of total protein by appropriate dilution with RIPA buffer followed by addition of 5× sample buffer. The samples were boiled for 5 min and then subjected to electrophoresis on either a 5% or 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, depending on the size of the viral protein. Proteins on gels were transferred to a 0.45-μm nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH) using standard methodology. In general, transfer times and voltage were varied based on protein size, ranging from 2 to 16 h at a voltage of 30 to 150 V, respectively. Once blotting was done, an ELISA-based immune detection assay was performed using a multichannel Western blot device from Bio-Rad. Nonspecific binding was blocked with 4% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 0.1% Tween (vol/vol)-Tris-buffered saline (TBS) buffer (TTBS) for 1 h, and then the membranes were directly incubated with an anti-FLAG murine monoclonal antibody or human polyclonal serum samples at ambient temperature for an additional 1 h. Following incubation, two washes of 5 min each with TTBS were performed, and rabbit anti-murine Ig or goat anti-human antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) at a dilution of 1:104 was added for 1 h at ambient temperature. Finally, the membranes were washed twice prior to development by chemiluminescence.

Following the final membrane washing, the immune-reactive viral proteins were visualized using Santa Cruz Biotechnology Western blot luminol reagents (catalog no. sc2048). Briefly, 500 μl of reagents A (Luminol) and B (hydrogen peroxide), mixed at a ratio of 1:1, were incubated on the blotted membrane for a period of 15 to 30 s. The membrane was then gently dried, and Fuji X-ray film was then exposed to the membranes for 30 to 60 s. Films were then developed for visualization. Validation and analysis of viral recombinant protein bands were aided by a broad-range protein marker (Fermentas SM0671) that was present on every blot.

Indirect ELISA for the detection of IgG specific antibodies (i) Procedure for chemiluminescence indirect ELISA.

The ELISA procedure was based on a previously described method (30), with several modifications. A 100-μl volume of total cell lysate expressing the recombinant viral protein (antigen) or cell lysate (mock antigen) at a concentration of 15 μg/well, or 2 μg/ml of purified GP1–649 in PBS without Mg+2 and Ca+2, pH 7.4, was passively adsorbed onto ELISA plates (MaxiSorp, Nunc, Denmark) overnight in a humidity chamber at +4°C. After incubation, plates were washed three times with 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (Sigma) in PBS; the same washing procedure followed each subsequent stage of the assay. Plates were blocked with 10% (vol/vol) skim milk (Merck) in PBS. After incubation at 37°C for 1 h, plates were washed, and triplicate volumes of 100 μl of each tested serum and controls diluted 1:400 were added to wells containing the viral protein and mock antigens. Further controls, including an anti-FLAG murine monoclonal antibody, goat anti-SUDV antiserum, and murine anti-GP1–649 monoclonal antibodies, were added at a dilution of 1:1,000, 1:3,000, and 1:1,000, respectively. After incubation for 1 h at 37°C, plates were washed, and a volume of 100 μl goat anti-human IgG (H+L chain) HRP conjugate (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) diluted 1:10,000 was added to wells. For Flag, GP1–649, and goat antibody controls, a volume of 100 μl goat anti-mouse and donkey anti-goat IgG HRP conjugate (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog no. sc-2005/sc-2020), diluted 1:10,000, were added to the wells, respectively. After incubation, plates were washed, and 40 μl of oxidizing reagent (H2O2) and enhanced luminal reagent solutions (NEL105 chemiluminescence reagent kit) were loaded into the well in a 1:1 ratio. Plates were then measured using a standard luminometer (Thermolabsystems-Luminoskan Ascent). The data were collected using the Luminoskan Ascent software program, and the mean and standard deviation of triplicates were calculated for each point, with the signal being reported in relative light units (RLU).

(ii) Normalization of raw data and selection of cutoff values.

Raw ELISA data were converted to signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) values. Calculation of S/N values was done as previously described (37), using the following formula: average result of control or test sera/negative internal control serum. The cutoff value for IgG positivity was determined by using a 10-fold stratified cross-validation analysis (13). For GP1–649, ELISA raw data were converted to percent positivity of a high internal control antibody (PP). Calculation of PP values was performed as previously described (30) using the following equation: (mean net of test sample/mean net of high-positive control) × 100.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using the OriginPro 8.5 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA) and SigmaPlot (Systat) software programs.

RESULTS

Establishment of a serum sample database.

To identify differences in the humoral immune response between survivors and victims of SUDV-gul infection in human, a serum sample database was established at the Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI), Entebbe, Uganda. This database consists of a collection of serum samples from the SUDV-gul outbreak in Uganda in 2000-2001 (18). A total of 178 serum samples (from both victims and survivors) were collected, of which 78 were validated to be from humans infected with SUDV and positive for Ebola virus antigen (16, 18), Ebola virus RNA (by reverse transcription-PCR), or IgG antibodies (15, 16, 18). One hundred samples were from noninfected close contacts and family members that were negative for Ebola virus according to reverse transcription-PCR and SUDV Ag ELISAs. Additionally, these patients were negative for anti-SUDV IgM and IgG according to assays performed during the outbreak (18).

Construction of expression plasmids for recombinant viral proteins of Sudan Ebola virus strain Gulu.

For detection of specific antibodies in patient sera by Western blotting and ELISA, we cloned all genes of SUDV-gul into expression vectors for production of viral recombinant proteins in eukaryotic cell culture. Sequence analysis of the clones demonstrated several nucleotide variations, compared to previous sequence data (36), in four of the seven individual genes of the virus: NP, VP35, VP30, and L (Fig. 1). These variations are present in the viral RNA template used during the construction and reflect the natural variation in sequence of viral genomes when using RNA from a different isolate (obtained during the same outbreak). Following cloning of the viral genes, a second set of expression constructs was generated for all viral proteins containing a Flag tag epitope (N-DYKDDDDK-C) marker. The Flag tag was selected for identification and purification of the viral proteins and was fused to either the C termini or the N termini of the viral proteins, as presented in Fig. 1. To produce the GP1–294-Flag tag recombinant protein, a slightly different approach was taken. Using the full-length GP transmembrane clone as the template, the first 294 amino acids of the protein (GP1–294) were subcloned and fused to the Flag marker. This construct contains the first shared 294 amino acids of the secreted GP (sGP) and GP1. A recombinant form of GP containing residues 1 to 649 of the mature protein was produced as described in Materials and Methods.

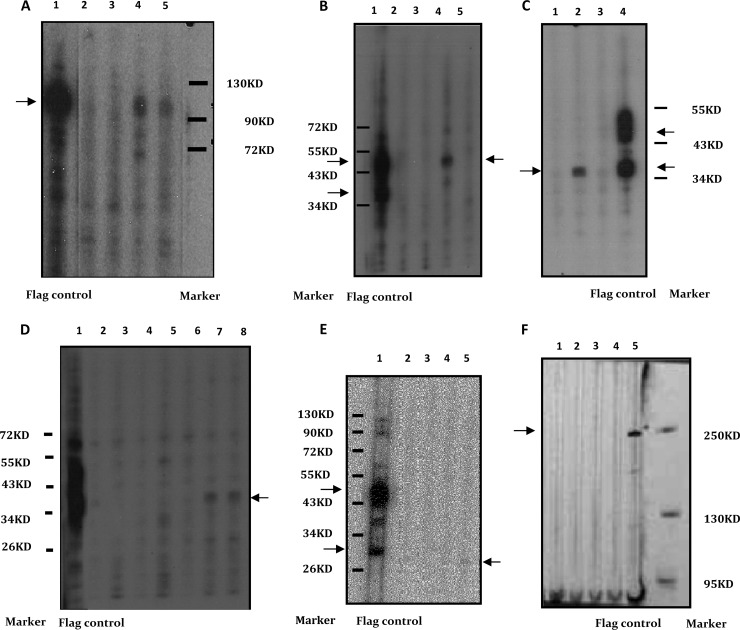

Western blot analysis. (i) Detection of recombinant viral proteins.

The detection of recombinant viral proteins of SUDV-gul in transfected cell lysates was performed using a monoclonal mouse anti-Flag antibody. Using a standard Western blot technique, transfected 293T cell lysates expressing individual tagged viral proteins (and controls) were blotted individually, or as a mixture of two, on nitrocellulose membranes and incubated with anti-Flag antibody. The expected molecular weights for all viral proteins, VP24, VP30, VP35, VP40, NP (nucleoprotein), GP1–294, and L (polymerase), were observed (Fig. 2). The results, presented in Fig. 2, display a slight shift in the expected migration of the SUDV-gul viral protein molecular weights due to the Flag tag marker. An expected molecular weight for the recombinant GP1–649 was also observed (data not shown). All expressed viral proteins were also blotted with polyclonal goat anti-SUDV antiserum. This antiserum (produced by inoculation with whole virus) detected only four of the seven viral proteins (i.e., VP24, VP30, VP40, and NP) of the virus (data not shown). Total cell protein lysates of nontransfected cells and cells transfected with empty vector were used as negative controls in all experiments and were not recognized by either the anti-Flag antibody or goat anti-SUDV serum controls.

Fig 2.

(A to F) Western blot analysis results for serum samples using a multichannel protein screening device (Bio-Rad). The expressed recombinant viral proteins of SUDV-gul were blotted individually, or in a mix of two, against a panel containing infected and noninfected samples from the original 2000-2001 outbreak (and validated at that time). A mouse anti-Flag commercial antibody was used as a positive control. All positive immunoreactive serum samples were also screened against a control antigen (lysates of 293T cells expressing pCAGGS without the recombinant proteins of SUDV-gul, for which there was no immunoreactivity in any of the samples [data not shown]). Select serum samples screened on these blots are presented. (A) Screening of four serum samples, of which two were from the noninfected group (lanes 2 and 3) and two from the infected group (lanes 4 and 5) against NP. Positive immunoreactivity is shown in lanes 4 and 5. (B) Screening of four serum samples, of which two were from the noninfected group (lanes 2 and 3) and two from the infected group (lanes 4 and 5), against VP30 and VP40. Positive immunoreactivity against VP40 is shown in lane 4. (C) Screening of three serum samples, of which two were from the infected group (lanes 1 and 2) and one from the noninfected group (lane 3) against VP30 and VP40. Positive immunoreactivity against VP30 is shown in lane 2. (D) Screening of seven serum samples, of which four were from the noninfected group (lanes 2 to 5) and three from the infected group (lanes 6 to 8), against GP1–294 and VP35. Positive immunoreactivity against VP35 is shown in lanes 7 and 8. (E) Screening of four serum samples, of which two were from the noninfected group (lanes 2 and 3) and two from the infected group (lanes 4 and 5) against VP24 and VP40. Positive immunoreactivity against VP24 is shown in lane 5. (F) Screening of four serum samples, of which two were from the noninfected group (lanes 1 and 2) and two from the infected group (lanes 3 and 4), against the viral protein L. No positive immunoreactivity was detected.

(ii) Serological screening by Western blotting.

A total of 178 individual serum samples were collected and analyzed during the 2000-2001 outbreak in Gulu, Uganda. Out of these, 78 were from infected patients and 100 from noninfected patients that served as a negative group of closely related individuals (no clinical signs of hemorrhagic fever and negative test results during the outbreak for Ebola virus by reverse transcription-PCR and ELISAs) (18). Western blot-based screening results for the set of 78 samples from infected patients for anti-SUDV-gul IgG are summarized in Table 1. In total, immunoreactivity was observed for six of the eight recombinant viral proteins (represented in Fig. 2). Overall, 23 serum samples were positive against at least one protein, with 21 serum samples seropositive for the recombinant NP (Fig. 2A), 4 samples for VP40 (Fig. 2B), 2 samples each for VP35 (Fig. 2D) and VP24 (Fig. 2E), and 1 sample each for GP1-294 and VP30 (Fig. 2C). No immunoreactivity against the viral proteins L and GP1-649 was detected. Screening results for the 100 noninfected samples from closely related individuals demonstrated a total of 6 with seropositive immunoreactivity against at least one SUDV-gul recombinant protein (Table 1).

Table 1.

Western blot summary of serum immunoreactivitya

| Sample group | No. of samples immunoreactive to SUDV-gul recombinant protein/no. tested |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VP24 | VP30 | VP35 | VP40 | NP | GP1–294b | GP1–649c | L | |

| Infectedd | 2/78 | 1/78 | 2/78 | 6/78 | 21/78 | 1/78 | 0/78 | 0/78 |

| Survivors | 1/54 | 1/54 | 2/54 | 4/54 | 16/54 | 0/54 | 0/54 | 0/54 |

| Victims | 0/12 | 0/12 | 0/12 | 0/12 | 1/12 | 1/12 | 0/12 | 0/12 |

| No info. | 1/12 | 0/12 | 0/12 | 2/12 | 4/12 | 0/12 | 0/12 | 0/12 |

| Noninfectede | 2/100 | 1/100 | 0/100 | 0/100 | 2/100 | 2/100 | 0/100 | 0/100 |

| Total | 4/178 | 2/178 | 2/178 | 6/178 | 23/178 | 3/178 | 0/178 | 0/178 |

Serum samples were divided into 2 different groups: positively infected for SUDV-gul and noninfected. Individual recombinant proteins of SUDV-gul were expressed in 293T cells, and cell lysates were screened by Western blotting. A purified recombinant protein containing the 649 amino-terminal amino acids of GP without the transmembrane domain was also used. The summary of results presented in Table 1 indicates that of the seven different recombinant proteins tested, the NP (nucleoprotein) was the most immunogenic, followed by VP40. Further analysis of positive immunoreactivity according to the outcome of the disease (survivors, death, and unknown) has shown that the majority of serum samples positive against the viral proteins were observed within the group of survivors. No immunorecognition was observed against GP1–649 and L.

A recombinant protein designed from the first 294 amino-terminal amino acids of GP1 and sGP.

A purified recombinant protein containing the 649 amino-terminal amino acids of GP without the transmembrane domain.

Out of the 78 SUDV-gul-infected samples, 54 were identified as samples from survivors and 12 from fatal cases (victims), and for 12 samples, there was no information available (no info.). Identification of humans infected with Ebola virus was performed in Uganda during the course of the outbreak in 2000-2001 using ELISA-based assays for the detection of Ag and Ig and by PCR.

Noninfected samples collected from close contacts and family members negative for Ebola virus Ag and antibodies according to assays performed during the outbreak (18).

ELISA. (i) Assay development.

Based on the Western blot results, an ELISA was developed using five viral recombinant proteins (NP, VP30, VP40, GP1–294, and GP1–649) of SUDV-gul. For each recombinant viral protein, calibration curves describing the general behavior of the IgG detection system (data not shown), as well as upper and lower control limits for internal quality controls (IQC), i.e., positive, negative, and goat anti-SUDV-gul (data not shown), used in the IgG indirect ELISA, were determined. In addition, cutoff values for positive IgG samples were also determined (Table 2) for each protein individually using 10-fold stratified cross-validation analysis (13), using the group of 100 human serum samples collected from healthy patients during the outbreak as an uninfected negative-control group (18).

Table 2.

ELISA analytical parametersa

| Analytical parameter | S/N, PP, or LLD value for SUDV-gul recombinant protein |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VP30 | VP40 | NP | GP1–294b | GP1–649c | |

| Assay controlsd | |||||

| Negativee | 0.82 (S/N) | 0.79 (S/N) | 0.88 (S/N) | 0.81 (S/N) | 0.05 (PP)i |

| Positivef | 3.71 (S/N) | 11.58 (S/N) | 13.32 (S/N) | 2.1 (S/N) | 0.8 (PP) |

| Goat anti-Ebola Sudang | 14.91 (S/N) | 57.16 (S/N) | 31.19 (S/N) | 0.45 (PP) | |

| Cutoff selection | 1.85 (S/N) | 1.4 (S/N) | 1.95 (S/N) | 1.3 (S/N) | 0.10 (PP) |

| LLDh | 1:6,400 | 1:6,400 | 1:12,800 | 1:6,400 | 1:12,800 |

ELISA analytical parameters for viral proteins: NP, VP30, VP40, GP1–294, and GP1–649 of SUDV-gul. Signal-to-noise (S/N) and positive percentage (PP) results of human positive, negative, and goat anti-Ebola virus controls used in the assay, as well as cutoff selection and low limit of antibody detection (LLD), are presented.

A recombinant protein designed from the first 294 amino-terminal amino acids of GP1 and sGP.

A purified recombinant protein containing the 649 amino-terminal amino acids of GP without the trans-membrane domain.

Average results were calculated from eight different ELISA experiments performed over a period of 8 weeks.

The negative control was obtained by pooling serum collected in 2003 in Uganda from 10 healthy volunteers who were never exposed to the virus.

The positive control was obtained by pooling serum from five human survivors infected with SUDV-gul during the 2000-2001 outbreak in Uganda and known to contain anti-Ebola virus IgG.

Goat anti-SUDV serum was used as second positive control.

The lower limit of detection was calculated as the highest serum dilution that demonstrated an S/N ratio of positive to negative or PP value that was above the calculated cutoff value.

Raw data were converted to percent positivity of a high internal control antibody (PP). Calculation of PP values was performed as previously described (29) using the following equation: mean net of test sample/mean net of high-positive control.

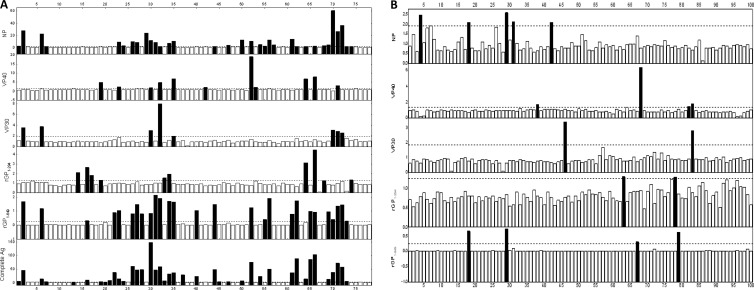

(ii) ELISA serological screening.

A summary of the ELISA screening results for IgG against the recombinant viral proteins NP, VP40, VP30, GP1–294, GP1–649, and the inactivated SUDV complete antigen are summarized in Table 3 and Fig. 3. Overall, out of 78 samples from infected patients, 48 serum samples were positive for a recombinant viral protein and/or intact virus. Out of these seropositive samples, 33 samples were positive for the recombinant NP, 27 for GP1-649, 11 for VP40, 10 for GP1-294, and 7 for VP30 (Fig. 3A). Comparison of immunoreactive (positive) results of the recombinant viral proteins of SUDV-gul to complete viral antigen revealed that 40 serum samples were positive for inactivated SUDV complete antigen. Screening results of the 100 samples in the noninfected control group revealed 13 samples with seropositive immunoreactivity against a recombinant viral protein or intact SUDV-gul (Fig. 3B).

Table 3.

ELISA summary of serum immunoreactivitya

| Sample group | No. of samples immunoreactive to protein/no. tested |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUD–gul recombinant protein |

SUDV complete antigend | |||||

| VP30 | VP40 | NP | GP1–294b | GP1–649c | ||

| Infectede | 7/78 | 11/78 | 33/78 | 10/78 | 27/78 | 40/78 |

| Survivors | 7/54 | 8/54 | 27/54 | 6/54 | 26/54 | 34/54 |

| Victims | 0/12 | 1/12 | 3/12 | 1/12 | 0/12 | 2/12 |

| No info. | 0/12 | 2/12 | 3/12 | 3/12 | 1/12 | 4/12 |

| Noninfectedg | 1/100 | 2/100 | 5/100 | 2/100 | 4/100 | 2/40f |

| Total | 8/178 | 13/178 | 38/178 | 12/178 | 31/178 | 42/118 |

Serum samples were divided into 2 different groups, infected with SUDV-gul and noninfected, and were screened against the viral proteins NP, VP40, VP30, GP1–294, and GP1–649 of SUDV-gul. The summary of ELISA results indicates that of the four different recombinant proteins tested, NP was the most immunogenic, followed by GP1–649. Further analysis of positive immunoreactivity according to the outcome of the disease (survivors, death, and unknown) demonstrates that the majority of serum samples positive against the viral proteins NP, GP1–649, VP40, GP1–294, and VP30 were observed within the group of survivors. SUDV complete Ag-positive immunoreactivity results were also observed to be associated with the group of survivors. In total, 12 out of the 78 samples could not be associated with survivors or fatal cases due to lack of information.

A recombinant protein designed from the first 294 amino-terminal amino acids of GP1 and sGP.

A purified recombinant protein containing the 649 amino-terminal amino acids of GP without the transmembrane domain.

SDS-inactivated SUDV Ag provided by S. Becker from Philipps University, Marburg, Germany.

Out of the 78 SUDV-gul-infected samples, 54 were identified as samples from survivors and 12 from fatal cases (victims), and for 12 samples, there was no information available (no info.). Identification of humans infected with Ebola virus was performed in Uganda during the course of the outbreak in 2000-2001 using ELISA-based assays for the detection of Ag and Ig and by PCR.

Out of the 100 negative samples, 40 were selected randomly and tested for selection of positive to negative cutoff.

Noninfected samples collected from close contacts and family members negative for Ebola virus Ag and antibodies according to assays performed during the outbreak (18).

Fig 3.

(A and B) ELISA immunoreactivity screening results of the SUDV-gul-infected (A) and noninfected (B) human serum sample groups against the different recombinant viral proteins NP, VP30, VP40, GP1–294, and GP1–649 and SUDV complete Ag. Each sample was tested in triplicate and screened against a total lysate of cells expressing a given recombinant viral protein and against expressed mock antigen (total cell lysate not expressing viral protein). The S/N results in the infected serum group (A) demonstrated that the greatest immunoreactivity was directed against the recombinant viral protein NP (33 samples), followed by GP1–649 (27), VP40 (11), GP1–294 (10), and VP30 (7). The immunoreactivity result using an inactivated SUDV complete Ag showed a high number of positive recognitions (40 samples), strongly associated with positive NP recognition. The S/N results in the noninfected serum group (B) demonstrated in total a very low number of positive immunoreactivities, primarily directed against NP (5), GP1–649 (4), and VP40 (4). The result of immunoreactivity against an inactivated SUDV complete Ag using 40 random noninfected samples revealed two positive immunoreactive samples (data not shown).

IgG immunoreactivity and disease outcome.

Data analysis was performed to understand whether positive IgG was detected within the group of samples collected from individuals who subsequently survived the viral infection. From a total of 78 SUDV-gul-infected samples from clinically and diagnostically positive patients, 54 samples were identified to be from individuals that survived the disease and 12 from fatal cases, and for 12 samples there was no information available. A summary of the screening results for the infected SUDV-gul patients against the recombinant viral proteins VP30, VP40, NP, GP1–294, and GP1–649 according to disease outcome are presented in Tables 1 and 3. Overall, as expected, the majority of serum samples positive against the recombinant viral proteins were within the group of survivors in both Western blots (Table 1) and ELISA (Table 3). SUDV complete Ag-positive immunoreactive results were also observed to be associated with the group of survivors, 34 of 40 (by ELISA).

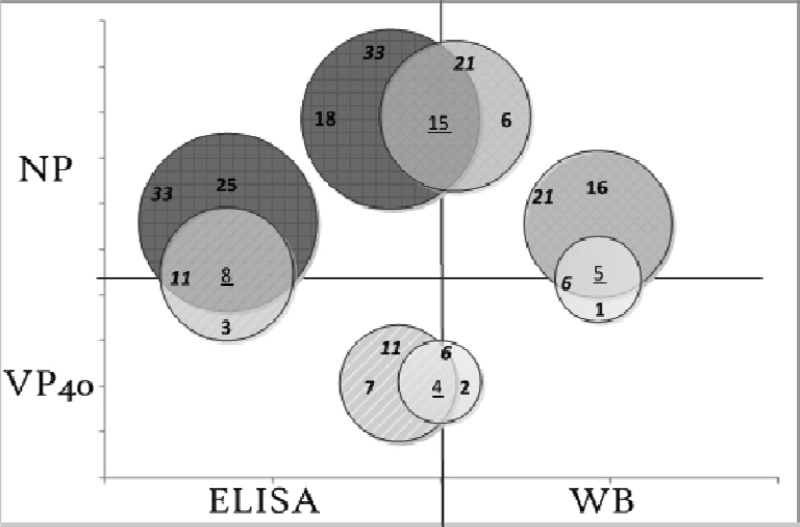

Comparison of ELISA and WB data for NP and VP40.

A comparison of data of positive immunoreactivity between the Western blot assay and the ELISA for the recombinant viral proteins NP and VP40 of SUDV-gul was performed. The results presented in Fig. 4 showed that for NP, a total of 21 samples were positive by Western blotting and 33 by ELISA. Out of these, 15 samples were positive in both assays, 6 were positive only by Western blotting, and 18 were positive only by ELISA. VP40 results demonstrated that in total, 6 samples were positive by Western blotting and 11 samples by ELISA. Out of these, 4 samples were positive in the two assays, 2 only by Western blotting, and 7 only by ELISA. Comparison of positive immunoreactivity between VP40 and NP demonstrated a high correlation. In total, 5 out of 6 samples of VP40 were positive for NP in the WB assay and 8 out of 11 in the ELISA.

Fig 4.

Schematic representation of the correlation between the recombinant viral proteins NP and VP40 of SUDV-gul positive sample recognition in Western blots (WB) and ELISAs. Data analysis of positive immunoreactivity between assays showed that for NP, a total of 21 samples were detected by Western blotting and 33 by ELISA. Out of these, 15 samples were positive in both assays, 6 only by Western blotting, and 18 only by ELISA. VP40 results demonstrated that in total, 6 samples were detected by Western blotting and 11 samples by the ELISA. Out of these, four samples were detected in both assays, two only by Western blotting and seven only by ELISA. Comparison of positive immunoreactivity between VP40 and NP in each assay demonstrated a correlation of 80% (5 out of 6 samples of VP40 were positive for NP) in the Western blot assay and 81% (8 out of 11 of VP40 were positive for NP) in the ELISA.

DISCUSSION

Humoral immunity in human and nonhuman primates clearly plays a major role in preventing many viral infections and contributes to resolution of infection. Previous work with immunocompetent small animal models (10, 11, 34, 41) has demonstrated that antibodies to Ebola virus proteins were capable of protecting against lethal Ebola virus challenge. Such protection was also recently demonstrated in nonhuman primates (9, 24, 33). However, despite these encouraging results, the efficacy of treatment requires further study, and thus far there is still no evidence from human cases demonstrating a conclusive role for antibodies in prophylaxis and therapy (15, 23, 27).

This article describes an initial study of the profile of the native specific human humoral immune response against viral proteins of SUDV-gul from sera obtained from infected individuals during the outbreak in Gulu, Uganda, during 2000-2001. The major goal of this study was to characterize the profile of humoral immunoreactivity during Ebola virus infection in humans and to understand if a specific profile of serum immunoreactivity existed in survivors. These data can be useful for the design of future cocktails of human monoclonal antibodies for prophylaxis and therapy (24).

The results demonstrate that the majority of immunoreactivity in patients is directed against the viral protein NP and GP1–649, which is consistent with previous studies indicating that these proteins are highly immunogenic (4, 31, 39, 42). Further comparison of these proteins' immunoreactivity levels to that of inactivated SUDV complete antigen, in our newly developed ELISA, demonstrated a high correlation between the two, suggesting that individual recombinant proteins may be useful in ELISA format for Ebola virus serology. Following these two viral proteins, VP40 displayed the highest number of reactive serum samples. It is not clear whether this high level of immunoreactivity against VP40 results from the abundance of the VP40 protein during viral replication or is due to its immunogenicity. Overall, most of the positive immunoreactivity was to either of these viral proteins, with several patients displaying immunoreactivity to some of the other viral proteins.

The controls employed in this study and used for validation and calibration of the assays consist of 100 negative serum samples (from patients' family members and close contacts that tested negative by ELISA and PCR during the original outbreak and were never diagnosed with EHF disease). This large bank of negative-control sera was a key component of our work because it facilitated a determination of appropriate cutoff values for the ELISA with samples from individuals closely related to the reference cases (18, 29). This indeed is one of the strengths of the ELISA that was developed for this study. Several of these negative controls tested positive to individual viral proteins in the assay. These assumed “false” positives, which are not uncommon for serological diagnostics of Ebola virus (14, 15), may be due to nuances of the assay compared to other assays or might reflect subclinical infections, as previously suggested (5, 6). However, the number of these positives was relatively low, and all of them reacted against only one viral protein or whole virus but not both. In contrast, all of the positive cases analyzed (consisting of samples from patients with confirmed Ebola virus infection) were typically positive to both whole virus and one or more viral proteins. As such, a profiling ELISA, as developed in this study for specific viral proteins, might facilitate identification and exclusion of false positives.

Analysis of total immunoreactivity results between ELISA and Western blotting revealed that ELISA detected a higher number of positive samples. Since it is well known that most antibodies react with, and are specific for, antigen in its native conformation, it came as no surprise that the “linear” immune recognition in the Western blot assay demonstrated less positive IgG recognition than ELISA. Although these results emphasize the importance of conformational recognition, a high correlation of positive immunoreactivity was observed between the two assays. Data analysis also confirmed results of previous studies, which revealed that nearly all immunoreactivity (in this study to NP, GP1–649, VP40, and VP30 [in ELISA]) was in the group of survivors rather than fatal cases.

Comparison of positive immunoreactivity between the two different recombinant forms of GP (by ELISA) clearly revealed a greater number of samples positive against GP1–649 than GP1–294, which represents the first 294 amino-terminal amino acids shared by sGP and previously suggested to be immunogenic (20, 21). The results we obtained with GP1–294 may be in part due to incorrect folding of this truncated protein or the fact that this domain may not be as well exposed on the complete, native sGP and GP proteins. However, these results were not surprising since previous studies demonstrated that significant humoral immunity targets other domains of GP, such as the mucin-like domain and the internal fusion loops (19, 32, 38, 43). In contrast to the ELISA, Western blot analysis demonstrated no immunoreactivity against the two forms of GP in the group of Ebola virus patients. These results suggest that positive humoral immunoreactivity against GP is likely a function of conformation. However, recognition of the “linear” mucin-like domain was expected. Therefore, further analysis with different domains of GP and deletion clones, including the secreted GP protein, needs to be performed.

This study has several limitations in that the recombinant expression system is only a mimic of the native viral proteins expressed during infection, albeit a good model since a eukaryotic expression system was employed. In addition, the assay was limited by the availability of serum samples from the outbreak in 2000-2001. Furthermore, the serum samples used in this study were collected over a period of 3 weeks during the outbreak in the month of October 2000. Despite extensive efforts, data regarding the stage of infection during phlebotomy, as well as the time of first exposure, for this patient cohort could not be obtained. Since it was previously suggested that survivors of Ebola develop a strong humoral immune response, it is likely that the results demonstrating only 34 positive immunoreactive samples out of the 54 survivors might in part be a result of sample collection during an early acute phase of disease in some patients before a significant humoral immune response was mounted. However, it has been noted that not all survivors of EHF display a humoral immune response, and these results may also reflect this unexplained observation. Overall, the results reveal that an ELISA, based on four of the individual viral proteins of SUDV-gul, demonstrated the ability to efficiently detect specific IgG in human serum samples and to identify profiles that may be useful for directing future research. Thus far, epitope-specific antibodies in survivors of SUDV that are targets of a successful adaptive immune response have not been identified. It is clear that understanding the role of specific antibodies in prophylaxis and therapy is key, as is identification of specific epitope targets of the viral proteins that might mediate protection from infection. The ELISA developed in this work provides an efficient tool for analysis of the protein-specific immune response following Ebola virus infection. In this study, the use of chemiluminescence for signal detection demonstrated its utility as an ultrasensitive analytical tool, enabling precise and sensitive quantitative analysis. In addition, this assay is especially powerful in that cutoff values were derived from a large negative-control group that was matched closely to the affected cohort. The use of recombinant engineered reagents in the development of sensitive and specific assays will facilitate investigations of Ebola viruses in developing and developed countries lacking high-containment facilities and will hopefully promote new Ebola virus diagnostics and vaccine development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the support of the National Institute of Biotechnology in the Negev, Beer-sheva, Israel, and the Feldman Family Foundation.

We thank the Ugandan Virus Research Institute for their enthusiastic support of this work and their assistance in obtaining the samples that were part of this study.

No author of this study has any conflict of interest regarding this research whatsoever.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 19 September 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Ascenzi, et al. 2008. Ebolavirus and Marburgvirus: insight the Filoviridae family. Mol. Aspects Med. 29:151–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baize S, et al. 1999. Defective humoral responses and extensive intravascular apoptosis are associated with fatal outcome in Ebola virus-infected patients. Nat. Med. 5:423–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baize S, Leroy EM, Mavoungou E, Fisher-Hoch SP. 2000. Apoptosis in fatal Ebola infection. Does the virus toll the bell for immune system? Apoptosis 5:5–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bale S, et al. 2012. Structural basis for differential neutralization of ebolaviruses. Viruses 4:447–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Becquart P, et al. 2010. High prevalence of both humoral and cellular immunity to Zaire ebolavirus among rural populations in Gabon. PLoS One 5:e9126 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Busico KM, et al. 1999. Prevalence of IgG antibodies to Ebola virus in individuals during an Ebola outbreak, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1995. J. Infect. Dis. 179(Suppl 1):S102–S107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dias JM, et al. 2011. A shared structural solution for neutralizing ebolaviruses. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18:1424–1427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dolnik O, Kolesnikova L, Becker S. 2008. Filoviruses: interactions with the host cell. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65:756–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dye JM, et al. 12 March 2012. Postexposure antibody prophylaxis protects nonhuman primates from filovirus disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. doi:10.1073/pnas.1200409109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Feldmann H, et al. 2007. Effective post-exposure treatment of Ebola infection. PLoS Pathog. 3:e2 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0030002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gupta M, Mahanty S, Bray M, Ahmed R, Rollin PE. 2001. Passive transfer of antibodies protects immunocompetent and immunodeficient mice against lethal Ebola virus infection without complete inhibition of viral replication. J. Virol. 75:4649–4654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Johnson BK, et al. 1986. Seasonal variation in antibodies against Ebola virus in Kenyan fever patients. Lancet i:1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kohavi R. 1995. A study of cross-validation and bootstrap for accuracy estimation and model selection, p 1137–1143 Proc. 14th Int. Joint Conf. Artif. Intell., vol 2 Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc., San Francisco, CA [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ksiazek TG, et al. 1992. Enzyme immunosorbent assay for Ebola virus antigens in tissues of infected primates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:947–950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ksiazek TG, et al. 1999. Clinical virology of Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF): virus, virus antigen, and IgG and IgM antibody findings among EHF patients in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1995. J. Infect. Dis. 179(Suppl 1):S177–S187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ksiazek TG, West CP, Rollin PE, Jahrling PB, Peters CJ. 1999. ELISA for the detection of antibodies to Ebola viruses. J. Infect. Dis. 179(Suppl 1):S192–S198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kuhn JH. 2008. Filoviruses. A compendium of 40 years of epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory studies. Arch. Virol. Suppl. 20:13–360 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lamunu M, et al. 2004. Containing a haemorrhagic fever epidemic: the Ebola experience in Uganda (October 2000–January 2001). Int. J. Infect. Dis. 8:27–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee JE, et al. 2008. Structure of the Ebola virus glycoprotein bound to an antibody from a human survivor. Nature 454:177–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee JE, Saphire EO. 2009. Neutralizing ebolavirus: structural insights into the envelope glycoprotein and antibodies targeted against it. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 19:408–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leroy EM, Baize S, Debre P, Lansoud-Soukate J, Mavoungou E. 2001. Early immune responses accompanying human asymptomatic Ebola infections. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 124:453–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Leroy EM, et al. 2000. Human asymptomatic Ebola infection and strong inflammatory response. Lancet 355:2210–2215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. MacNeil A, et al. 2010. Proportion of deaths and clinical features in Bundibugyo Ebola virus infection, Uganda. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16:1969–1972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Marzi A, et al. 2012. Protective efficacy of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies in a nonhuman primate model of Ebola hemorrhagic fever. PLoS One 7:e36192 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mohamadzadeh M, Chen L, Schmaljohn AL. 2007. How Ebola and Marburg viruses battle the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7:556–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Muhlberger E, Weik M, Volchkov VE, Klenk HD, Becker S. 1999. Comparison of the transcription and replication strategies of Marburg virus and Ebola virus by using artificial replication systems. J. Virol. 73:2333–2342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mupapa K, et al. 1999. Treatment of Ebola hemorrhagic fever with blood transfusions from convalescent patients. International Scientific and Technical Committee. J. Infect. Dis. 179(Suppl 1):S18–S23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Murphy FA, et al. 1978. Ebola and Marburg virus morphology and taxonomy. Ebola virus haemorrhagic fever, p 61–84 Proc. Int. Colloquium Ebola Virus Infect. Other Haemorrhagic Fevers. Elsevier/North-Holland Biomedical Press, Amsterdam, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 29. Okware SI, et al. 2002. An outbreak of Ebola in Uganda. Trop. Med. Int. Health 7:1068–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Paweska JT, Burt FJ, Swanepoel R. 2005. Validation of IgG-sandwich and IgM-capture ELISA for the detection of antibody to Rift Valley fever virus in humans. J. Virol. Methods 124:173–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Prehaud C, et al. 1998. Recombinant Ebola virus nucleoprotein and glycoprotein (Gabon 94 strain) provide new tools for the detection of human infections. J. Gen. Virol. 79(Pt 11):2565–2572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Qiu X, et al. 2011. Characterization of Zaire ebolavirus glycoprotein-specific monoclonal antibodies. Clin. Immunol. 141:218–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Qiu X, et al. 2012. Successful treatment of Ebola virus-infected cynomolgus macaques with monoclonal antibodies. Sci. Transl. Med. 4:138ra181 doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3003876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Qiu X, et al. 2012. Ebola GP-specific monoclonal antibodies protect mice and guinea pigs from lethal Ebola virus infection. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6:e1575 doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sanchez A, et al. 2004. Analysis of human peripheral blood samples from fatal and nonfatal cases of Ebola (Sudan) hemorrhagic fever: cellular responses, virus load, and nitric oxide levels. J. Virol. 78:10370–10377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sanchez A, Rollin PE. 2005. Complete genome sequence of an Ebola virus (Sudan species) responsible for a 2000 outbreak of human disease in Uganda. Virus Res. 113:16–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sobarzo A, et al. 2007. Optical fiber immunosensor for the detection of IgG antibody to Rift Valley fever virus in humans. J. Virol. Methods 146:327–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Takada A, et al. 2003. Identification of protective epitopes on Ebola virus glycoprotein at the single amino acid level by using recombinant vesicular stomatitis viruses. J. Virol. 77:1069–1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Watanabe SN, Kawaoka TY. 2006. Functional mapping of the nucleoprotein of Ebola virus. J. Virol. 80:3743–3751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wauquier N, Becquart P, Padilla C, Baize S, Leroy EM. 2010. Human fatal Zaire Ebola virus infection is associated with an aberrant innate immunity and with massive lymphocyte apoptosis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 4:e837 doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wilson JA, Bosio CM, Hart MK. 2001. Ebola virus: the search for vaccines and treatments. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 58:1826–1841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wilson JA, Hart MK. 2001. Protection from Ebola virus mediated by cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for the viral nucleoprotein. J. Virol. 75:2660–2664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wilson JA, et al. 2000. Epitopes involved in antibody-mediated protection from Ebola virus. Science 287:1664–1666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]