Seven of 13 patients with Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)-producing Escherichia coli (E. coli) infection were identified as having isolates belonging to ST131, the international epidemic, multidrug-resistant clone. The isolates showed variable susceptibility to carbapenems. KPC-producing organisms other than E. coli were also identified in five of these patients.

Abstract

Background. Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)–producing K. pneumoniae has become endemic in many US hospitals. On the other hand, KPC-producing Escherichia coli remains rare.

Methods. We studied infection or colonization due to KPC-producing E. coli identified at our hospital between September 2008 and February 2011. A case-control study was conducted to document clinical features associated with this organism. Susceptibility testing, sequencing of β-lactamase genes, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, multilocus sequence typing, and plasmid analysis were performed for characterization of the isolates.

Results. Thirteen patients with KPC-producing E. coli were identified. The patients had multiple comorbid conditions and were in hospital for variable periods of time before KPC-producing E. coli was identified. The presence of liver diseases was independently associated with recovery of KPC-producing E. coli when compared with extended-spectrum β-lactamase–producing E. coli. The isolates showed variable susceptibility to carbapenems. Seven isolates belonged to sequence type (ST) 131, which is the international epidemic, multidrug-resistant clone, but their plasmid profiles were diverse. KPC-producing organisms other than E. coli were isolated within 1 month from 5 of the patients. The KPC-encoding plasmids were highly related in 3 of them, suggesting the occurrence of their interspecies transfer.

Conclusions. KPC-producing E. coli infections occur in severely ill patients who are admitted to the hospital. Acquisition of the KPC-encoding plasmids by the ST 131 clone, reported here for the first time to our knowledge in the United States, seems to represent multiple independent events. These plasmids are often shared between E. coli and other species.

Since its emergence a decade ago, Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)–producing K. pneumoniae has become endemic in many hospitals in the United States, as well as in countries on other continents [1]. The KPC gene is commonly encoded in a transposon structure on a transferable plasmid, thus enabling it to spread to other gram-negative species, particularly those in the Enterobacteriaceae. Of particular concern is its spread to Escherichia coli, which is part of our commensal and the most frequent cause of community-acquired urinary tract infection [2]. Several studies have documented the emergence of KPC-producing E. coli in the United States [3–6]. We previously reported a case in which interspecies transfer of the KPC gene was suspected among 3 species including E. coli [7].

E. coli is rapidly becoming resistant to fluoroquinolones and cephalosporins, which is driven by the worldwide dissemination of a specific multidrug-resistant clone defined by sequence type (ST) 131 [8]. E. coli ST 131 is most typically encountered in isolates producing CTX-M–type extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) [9, 10]. Two case reports have identified E. coli ST 131 producing KPC, but the extent of this phenomenon is not known [11, 12].

Since the initial case [7], we have seen an increasing number of KPC-producing E. coli at our hospital. The present study was conducted to elucidate the clinical and microbiologic features of KPC-producing E. coli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case Identification

E. coli isolates with nonsusceptibility to ertapenem were collected at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (Presbyterian and Shadyside Campuses) between September 2008 and February 2011. Reduced susceptibility to ertapenem is known to be the most sensitive indicator in screening for KPC production [13]. Possession of the KPC gene was screened by a simplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reaction and confirmed with sequencing of the PCR products [7]. Phenotypic testing for carbapenemase production and KPC production were also conducted using the modified Hodge test and the aminophenyl boronic acid test (APB), respectively [13, 14]. For the cases with KPC-producing E. coli, the microbiology database was searched to identify ertapenem-nonsusceptible non–E. coli species from the same patients within a 1-month period before and after the isolation of KPC-producing E. coli. These non–E. coli isolates were also subjected to PCR analysis for confirmation of possession of the KPC gene and used for subsequent plasmid analysis.

Case-Control Study

KPC-producing E. coli cases were grouped by age and sex. ESBL-producing, non–KPC-producing E. coli cases were selected as controls and were frequency matched to the case age and sex grouping so that the distribution of age and sex among controls was similar to that among cases. The case-control ratio was 1:3. Clinical information including demographics, type of infection, underlying medical conditions, previous contact with healthcare system, previous antimicrobial use, and presence of indwelling catheters were collected from deidentified medical records. Univariate logistic regression analyses were performed to determine risk factors for KPC-producing E. coli. Exact logistic regression was performed when one group did not have any members with a given risk factor, and the median unbiased estimate is reported instead of a P value for those cases. All variables with P values <.2 in the univariate model were eligible for inclusion in the multivariable model. A multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed in a stepwise manner with a stay criteria of P < .05 to determine independent risk factors. After determination of an initial model, variables that were not significant were removed from eligibility, and the analysis was run again to determine a final model. All tests were 2-tailed. SAS software, version 9.2, was used for the analysis (SAS Institute).

Susceptibility Testing

Susceptibility of the KPC-producing E. coli to various β-lactams was determined using the agar dilution method. Susceptibility to non–β-lactam antimicrobials was obtained by the broth microdilution method (Sensititre GN4F; TREK Diagnostic Systems). The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were interpreted according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [15]. For colistin, the break point for Pseudomonas aeruginosa was used. For tigecycline, the Food and Drug Administration break point for Enterobacteriaceae was used.

β-Lactamase Gene Identification and Phylogenetic Typing

PCR analysis was conducted to detect TEM-, SHV-, and CTX-M–type ESBL genes and also CMY-type acquired AmpC genes, as described elsewhere [16, 17]. All PCR products were sequenced to confirm genotypes that contributed to cephalosporin resistance. Phylogenetic typing was performed using the method published elsewhere [18].

Multilocus Sequence Typing and Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was performed on all KPC-producing E. coli isolates according to the protocol by Achtman et al [19]. Allelic profiling and ST determination was performed through the E. coli MLST website maintained at the University College Cork (http://mlst.ucc.ie/mlst/dbs/Ecoli).

The isolates were also subjected to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) to evaluate for genomic relatedness. Genomic DNA of the isolates were prepared as described elsewhere [20]. Fingerprints were generated by XbaI (New England Biolabs) and subjected to electrophoresis using a CHEF DR III system (Bio-Rad). The relatedness of PFGE patterns was determined by unweighted-pair group method using average linkages and the DICE setting clustering analysis on Bionumerics software, version 6.0 (Applied Maths).

Plasmid Analysis

To characterize the plasmids bearing the KPC gene among the E. coli isolates, as well as isolates of other species from the same patients, transfer of the plasmids was performed by conjugation or transformation. Conjugation was performed by liquid mating in lysogenic broth with E. coli J53AziR as recipient. Transconjugants were selected on lysogenic agar containing 100 μg/mL sodium azide and 50 μg/mL ampicillin. Transformation was performed using electrocompetent E. coli DH10B, and plasmids were prepared from the clinical isolates. Transformants were selected on lysogenic agar containing 50 μg/mL ampicillin. Transfer of plasmids with the KPC gene was confirmed by PCR analysis. The plasmids were extracted from these transconjugants or transformants using the standard alkaline lysis method. Fingerprints of the plasmids were generated by digesting them with EcoRI or HpaI (New England Biolabs).

RESULTS

Clinical Features of Patients With KPC-Producing E. coli Infection

A total of 13 patients with infection due to KPC-producing E. coli was identified from the study period. Five were reported as ESBL-positive and the remainder negative by the clinical microbiology laboratory. The clinical features of the patients are summarized in Table 1. E. coli was isolated from urine (n = 6), intra-abdominal source (n = 4), bronchoalveolar lavage (n = 2), or blood (n = 1). The periods between hospital admission and identification of KPC-producing E. coli were highly variable (median, 1 day; mean, 49 days; range, 0–176 days). Six patients were transferred from a nursing home, and 1 patient from another hospital. Six were admitted from home, but they all had significant underlying comorbid conditions (Table 1). Ten patients were deemed to have infection due to this organism, whereas 3 patients were found to be colonized only. They were treated with a variety of definitive antimicrobial therapies, which included carbapenems, cefepime, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, amikacin, tigecycline, and colistimethate, alone or in combination. Of those with infection, 6 were alive and 3 had died 28 days after infection. Compared with patients with ESBL-producing E. coli, more patients with KPC-producing E. coli attended the hospital clinic or had liver disease. Of the two risk factors, only liver disease remained as an independent risk factor in multivariate analysis (odds ratio, 7.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.48–38.03; P = .01) (see Supplementary Table).

Table 1.

Clinical Features of 13 Patients With KPC-Producing Escherichia coli

| Patient | Age | Comorbid Conditions | Admitted From | Reason for Admission | Interval From Admission to Positive Culture, days | Culture Site | Infection or Colonization | Empiric Therapy | Definitive Therapy | Outcome at 28 days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 44 | Short gut syndrome, small-bowel transplant, diabetes | SNF | Graft rejection | 99 | JP drainage | Infection | Aztreonam | Meropenem Tigecycline | Survived |

| 2 | 65 | Cryptogenic cirrhosis, liver transplant, Crohn disease, diabetes | Home | Pyelonephritis | 0 | Urine | Infection | Cefuroxime | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, cefepime | Survived |

| 3 | 73 | Osteoarthritis, lumbar laminectomy, diabetes | Home | Wound infection | 0 | Urine | Colonization | NA | NA | Unknown |

| 4 | 34 | Multiple trauma from motor vehicle accident | Hospital | Wound infection | 121 | Abdominal drainage | Infection | Doripenem | Ciprofloxacin | Survived |

| 5 | 61 | Cryptogenic cirrhosis, liver transplant | Home | Exploratory laparotomy | 0 | Abscess | Infection | Ampicillin-sulbactam | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, imipenem | Survived |

| 6 | 74 | Diabetes, congestive heart failure | SNF | Acute renal failure | 1 | Urine | Colonization | NA | NA | Survived |

| 7 | 48 | Anoxic encephalopathy, diabetes | SNF | Fever | 0 | Urine | Infection | Nitrofurantoin, cefepime | Meropenem, colistimethate | Survived |

| 8 | 94 | Diabetes, recurrent urinary tract infection | Home | Mental status change | 0 | Urine | Infection | Cefepime | Ertapenem | Unknown |

| 9 | 33 | Hepatocellular carcinoma, diabetes | Home | Liver transplant | 57 | BAL | Infection | None | Tigecycline, ciprofloxacin, amikacin | Died |

| 10 | 63 | Diabetes, congestive heart failure | SNF | Chest pain | 1 | BAL | Colonization | NA | NA | Survived |

| 11 | 57 | Cirrhosis, diabetes, congestive heart failure | SNF | Acute renal failure | 52 | Blood | Infection | Cefepime | Cefepime | Survived |

| 12 | 42 | Budd-Chiari syndrome, multiorgan transplant | SNF | Anasarca | 135 | JP drainage | Infection | Colistimethate | Colistimethate, tigecycline | Died |

| 13 | 38 | Cirrhosis, diabetes | Home | Melena | 176 | BAL | Infection | Colistimethate, ampicillin-sulbactam | Colistimethate | Died |

Abbreviations: BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage specimen; KPC, Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase; JP, Jackson-Pratt [drain]; NA, not applicable; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

Five of 13 patients had ≥1 other species identified as producing KPC within 1 month from identification of KPC-producing E. coli. Patients 1, 12, and 13 had KPC-producing K. pneumoniae. Patient 4 had both KPC-producing Enterobacter cloacae and Klebsiella oxytoca. Patient 9 had KPC-producing Serratia marcescens.

Phenotypic Testing, Antimicrobial Susceptibility, and β-Lactamase Production of KPC-Producing E. coli

All KPC-producing E. coli isolates from the 13 patients had a positive modified Hodge test result, in which clover leaf-shaped distortion of the ertapenem disk zone of E. coli ATCC25922 occurred in the presence of these isolates. Results of the APB, the phenotypic confirmation test for KPC production, was positive in 12 isolates using ertapenem as the substrate and 300 μg of APB as the inhibitor, and a 5-mm zone difference as the cutoff. One isolate was read as negative because the zone difference was 4 mm.

Antimicrobial susceptibility is shown in Table 2. All isolates were resistant to piperacillin-tazobactam, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, and aztreonam, and many were resistant to cefepime as well. The MICs of carbapenems were variable and lower than what is typically observed with K. pneumoniae, consistent with a previous report [4]. Among non–β-lactams, aminoglycosides remained relatively active with 13, 9, and 8 isolates susceptible to amikacin, gentamicin, and tobramycin, respectively. Tetracyclines were also active, with 12 isolates susceptible to minocycline. Four isolates were susceptible to fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin), and all isolates were susceptible to tigecycline and colistin.

Table 2.

Antimicrobial Susceptibility, Phenotypic Testing, and β-Lactamase Contents of KPC-Producing Escherichia coli

| Patient | PTZ | CTX | CAZ | FEP | ATM | ERT | IPM | MEM | DOR | SXT | LEVO | CIP | AMK | GEN | TOB | DOX | MINO | TGC | COL | MHT | APB | ST | KPC | Other β-Lactamases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | >128/4 | 32 | >128 | 64 | 128 | 32 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 4/76 | ≤1 | 1 | ≤4 | ≤1 | ≤1 | 8 | ≤2 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | + | + | 964 | KPC3 | CMY-44, TEM-1 |

| 2 | >128/4 | 32 | >128 | 32 | >128 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | >4/76 | >8 | >2 | ≤4 | ≤1 | ≤1 | 8 | ≤2 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | + | + | 131 | KPC3 | TEM-1 |

| 3 | 128/4 | 4 | 32 | 2 | 128 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | >4/76 | >8 | >2 | ≤4 | ≤1 | ≤1 | 16 | 8 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | + | + | 131 | KPC2 | TEM-1 |

| 4 | 128/4 | 16 | >128 | 8 | >128 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | >4/76 | ≤1 | 0.5 | ≤4 | >8 | >8 | ≤2 | ≤2 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | + | + | 2521 | KPC3 | SHV-7, TEM-1 |

| 5 | >128/4 | 128 | >128 | 64 | >128 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | >4/76 | >8 | >2 | 8 | >8 | >8 | ≤2 | ≤2 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | + | + | 648 | KPC3 | SHV-7, TEM-1 |

| 6 | 128/4 | 8 | 128 | 4 | 128 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | >4/76 | >8 | >2 | 8 | ≤1 | >8 | ≤2 | ≤2 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | + | + | 131 | KPC2 | TEM-1 |

| 7 | >128/4 | 32 | 128 | 16 | >128 | 16 | 4 | 4 | 4 | >4/76 | >8 | >2 | ≤4 | ≤1 | ≤1 | 8 | ≤2 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | + | + | 131 | KPC2 | TEM-1 |

| 8 | >128/4 | 32 | >128 | 32 | >128 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | >4/76 | >8 | >2 | ≤4 | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤2 | ≤2 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | + | + | 131 | KPC3 | TEM-1 |

| 9 | >128/4 | 32 | 128 | 16 | 128 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | >4/76 | ≤1 | ≤0.25 | ≤4 | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤2 | ≤2 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | + | −a | 372 | KPC3 | none |

| 10 | 128/4 | 4 | 32 | 4 | 64 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | >4/76 | 8 | >2 | ≤4 | >8 | 8 | 8 | ≤2 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | + | + | 131 | KPC2 | TEM-1 |

| 11 | >128/4 | 128 | >128 | 64 | >128 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | >4/76 | >8 | >2 | ≤4 | ≤1 | ≤1 | 8 | ≤2 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | + | + | 131 | KPC3 | TEM-1 |

| 12 | 128/4 | 64 | >128 | 32 | >128 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 2 | >4/76 | ≤1 | ≤0.25 | ≤4 | ≤1 | 2 | ≤2 | ≤2 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | + | + | 404 | KPC2 | TEM-1 |

| 13 | 128/4 | 16 | 128 | 8 | >128 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 2 | >4/76 | >8 | >2 | ≤4 | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤2 | ≤2 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | + | + | 648 | KPC2 | SHV-12, TEM-1 |

Values represent minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) in micrograms per milliliter. MICs in the susceptible range according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute break points are shown in bold. For test results, plus signs indicate positive results.

Abbreviations:AMK, amikacin; APB, aminophenyl boronic acid test; ATM, aztreonam; CAZ, ceftazidime; CIP, ciprofloxacin; COL, colistin; CTX, cefotaxime; DOR, doripenem; DOX, doxycycline; ERT, ertapenem; FEP, cefepime; GEN, gentamicin; IPM, imipenem; KPC, Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase; LEVO, levofloxacin; MEM, meropenem; MHT, modified Hodge test; MINO, minocycline; PTZ, piperacillin-tazobactam; ST, sequence type; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; TGC, tigecycline; TOB, tobramycin.

a Marginally negative result with a zone diameter difference of 4 mm, at a cutoff of 5 mm.

In total, 6 and 7 isolates produced KPC-2 and KPC-3, respectively. Coproduction of ESBL or acquired AmpC was rather uncommon, with only 3 isolates producing SHV-type ESBL and 1 isolate producing CMY-44, a cefepime-hydrolyzing variant of CMY-2 [21]. Of note, none of them produced CTX-M–type ESBL, including CTX-M-15.

Phylogenetic Typing and Molecular Typing

In total, 9, 3, and 1 isolates belonged to phylogenetic groups B2, D, and B1, respectively. None belonged to group A. Phylogenetic groups B2 and D have been associated with extraintestinal infections, whereas groups A and B1 are generally considered commensals [22].

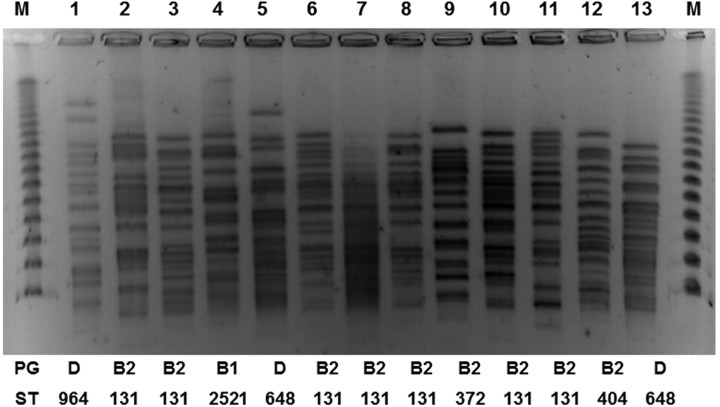

By MLST, 7 of the phylogenetic group B2 isolates belonged to ST 131. ST 131-B2 is the international epidemic, multidrug-resistant clonal lineage that is especially linked to CTX-M–type ESBLs [23, 24]. The remaining 2 group B2 isolates belonged to ST 372 and ST 404. Two of 3 group D isolates belonged to ST 648. ST 648-D has been associated with ESBLs and NDM-type metallo–β-lactamase and found in humans as well as animals [17, 25, 26]. The remaining group D isolate and the group B1 isolate belonged to ST 964 and ST 2521, respectively. ST 964-D has also been associated with CTX-M–type ESBLs [27]. ST 2521 is a single-locus variant of ST 446, which has been associated with CTX-M–type ESBLs as well [28]. The findings of molecular typing are summarized in Figure 1, along with the PFGE profile.

Figure 1.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis profiles, phylogenetic groups, and sequence types of 13 Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase–producing Escherichia coli isolates.

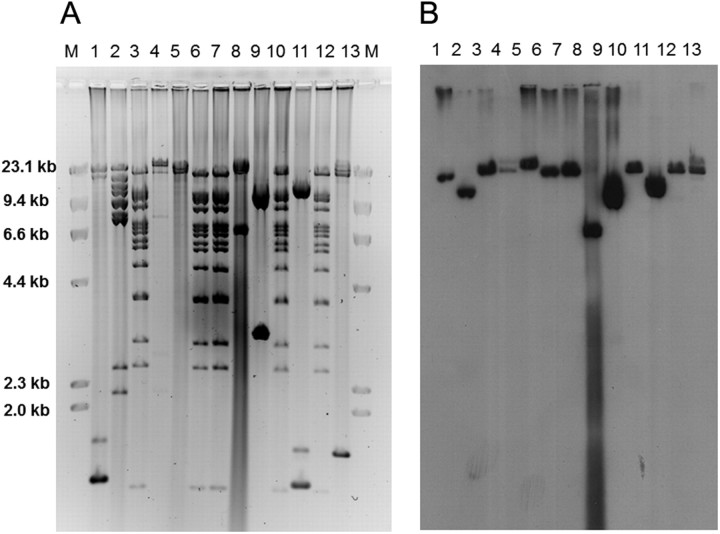

Plasmid Profiles

The restriction profiles of the plasmids encoding the KPC genes in E. coli are shown in Figure 2. Five of the plasmids showed identical restriction pattern. They included 4 ST 131 isolates and the ST 404 isolate. However, the remaining plasmids had distinct restriction patterns, including the other 3 ST 131 isolates, suggesting that both clonal spread and independent acquisition of various KPC-encoding plasmids are responsible for the emergence of KPC-producing ST 131 strains at our hospital.

Figure 2.

A, Plasmid profiles of 13 Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)–producing Escherichia coli isolates using restriction enzyme EcoRI. B, DNA hybridization using a probe specific to the KPC gene.

The restriction profiles of the plasmids of different species from the same patients were then examined (Figure 3). The profiles from patients 9, 12, and 13 matched well between E. coli and S. marcescens or K. pneumoniae. The profiles of E. coli and K. oxytoca from patient 4 showed some similarity as well, whereas those of E. coli and K. pneumoniae from patient 1 and E. cloacae from patient 4 were distinct.

Figure 3.

Plasmid profiles of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase–producing Escherichia coli–non–E. coli pairs from 5 cases using restriction enzyme HpaI. Lanes 1 and 2, E. coli and K. pneumoniae from case 1; lanes 3, 4, and 5, E. coli, Enterobacter cloacae, and Klebsiella oxytoca from case 4; lanes 6 and 7, E. coli and Serratia marcescens from case 9; lanes 8 and 9, E. coli and K. pneumoniae from case 12; lanes 10 and 11, E. coli and K. pneumoniae from case 13.

DISCUSSION

ESBL-producing E. coli have become prominent in the last decade. In a worldwide survey of urinary tract isolates conducted between 2009 and 2010, 17.9% of E. coli were ESBL positive [29]. The rapid rise in the rates of ESBL producers has been attributed to the emergence and expansion of a specific clone of E. coli, which is defined by serotypes O25b and ST 131 [10, 23, 24]. The emergence of ST 131 has coincided with the rise in the number of community-acquired ESBL-producing E. coli infection in many parts of the world [30, 31]. E. coli ST 131 is typically multidrug resistant, especially including resistance to fluoroquinolones, and most frequently described as producing plasmid-mediated CTX-M-15 ESBL [23, 24], although production of other types of ESBLs by this clone has also been documented [32, 33]. E. coli ST 131 was recently reported to be the most significant cause of antimicrobial-resistant E. coli infection in the United States as well [34]. For infection caused by ESBL-producing E. coli that are resistant to penicillins, cephalosporins, and frequently other classes of antimicrobials, carbapenems remain active and are routinely used for therapy. Emergence of carbapenem-resistant E. coli therefore threatens the viability of this therapeutic approach.

In the present study, we conducted detailed clinical and microbiologic analysis of 13 cases of KPC-producing E. coli we experienced at our hospital. Notably, we identified 7 isolates of E. coli ST 131 among the 13 study isolates (54%). This is the first study to our knowledge to report the emergence of KPC-producing ST 131 isolates in the United States. Of these ST 131 isolates, 4 shared the same plasmid encoding the KPC gene, suggesting spread of an ST 131 strain that has already acquired the KPC gene. However, the remaining 3 had distinct plasmids, which points to the possibility that ST 131 strains in the hospital environment are concurrently and independently acquiring plasmids or transposons encoding the KPC gene. In addition and to our surprise, none of the isolates produced CTX-M–type ESBLs. E. coli ST 131 has been reported to produce a variety of ESBLs other than CTX-M and acquired AmpC β-lactamases [8]. E. coli ST 131 without ESBLs is also carried in the stool of some healthy individuals [35]. Our findings further exemplify the ability of the ST 131 clone to acquire new resistance determinants under selective pressure. Although all the cases in the present study represented hospital-acquired or healthcare-associated infections, future spread of KPC-producing E. coli to the community needs to be carefully monitored, especially given the propensity of E. coli ST 131 to cause community-associated infections [8].

Another noteworthy finding was that 5 of the 13 KPC-producing E. coli cases were accompanied by ≥1 other species producing KPC identified within 1 month of each other in the same patients. The species were diverse and included K. pneumoniae, K. oxytoca, E. cloacae, and S. marcescens. They were isolated from the same anatomic sites as E. coli for 3 patients and blood for the remaining 2 patients. Plasmid profiling suggested direct transfer of KPC-encoding plasmids between E. coli and the other species in ≥3 of these cases. Transfer of the plasmids encoding the KPC gene between species within patients has been reported on several occasions, including from our hospital [7, 36, 37]. These reports have documented exportation of KPC-encoding plasmids from K. pneumoniae, which is the most common host of this gene, to other species. However, exchange of KPC-encoding plasmids with E. coli serving as the hub, as illustrated in the present study, is potentially a more substantial threat in the long term, because the species is part of the commensal flora that may serve as the host of the KPC gene beyond the period of acute illness.

The patients received various antimicrobial therapies, either alone or in combination, for treatment of KPC-producing E. coli infection. Although we were not able to correlate the therapy received and clinical outcome due to the small number of cases and heterogenous and ill patient population, the MIC data highlight differences between antimicrobial susceptibility of E. coli and K. pneumoniae that produce KPC. Although piperacillin-tazobactam and cephalosporins, including cefepime, are not expected to be effective, the MICs of carbapenems were relatively low with some isolates in the susceptible range, and most of them in the susceptible range if the CLSI break points before 2010 were applied, with the exception of ertapenem, raising the possibility that there may be a role for carbapenems at least in the context of combination therapy [38]. For the non–β-lactams, aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, tigecycline, and colistin showed good to excellent in vitro activity against KPC-producing E. coli. Overall, there still seem to be more therapeutic options available for this group of isolates than for KPC-producing K. pneumoniae [1].

Our study was limited by the relatively small number of patients with KPC-producing E. coli. During the study period, E. coli was isolated from a total of 9311 patients at our hospital, of which 322 isolates were due to ESBL-producing organisms. Thus, the proportion of KPC-producing E. coli is still quite low at our hospital.

In conclusion, KPC-producing E. coli infections occur in severely ill patients with prolonged or recent hospitalization. Acquisition of the KPC-encoding plasmids by the ST 131 clone seems to represent multiple independent events. These plasmids are often shared between E. coli and other species. This raises a concern that the KPC gene may spread to the community with E. coli ST 131, which is now a common culprit causing community-associated, multidrug-resistant infections.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online (http://cid.oxfordjournals.org). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank Lloyd Clarke and Diana Pakstis for database management and logistic support of the study, respectively. We are also thankful to Dr David Paterson for his critical review of the manuscript.

Financial support. This study was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health (grant R03AI079296; grant K22AI080584 to Y. D.).

Potential conflict of interest. Y. D. has received research funding from Merck and served on an advisory board for Pfizer. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Nordmann P, Cuzon G, Naas T. The real threat of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing bacteria. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:228–36. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foxman B. Epidemiology of urinary tract infections: incidence, morbidity, and economic costs. Am J Med. 2002;113(Suppl 1A):5S–13S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bratu S, Brooks S, Burney S, et al. Detection and spread of Escherichia coli possessing the plasmid-borne carbapenemase KPC-2 in Brooklyn, New York. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:972–5. doi: 10.1086/512370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landman D, Urban C, Backer M, et al. Susceptibility profiles, molecular epidemiology, and detection of KPC-producing Escherichia coli isolates from the New York City vicinity. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:4604–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01143-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urban C, Bradford PA, Tuckman M, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli harboring Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase β-lactamases associated with long-term care facilities. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:e127–30. doi: 10.1086/588048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robledo IE, Aquino EE, Vazquez GJ. Detection of the KPC gene in Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter baumannii during a PCR-based nosocomial surveillance study in Puerto Rico. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:2968–70. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01633-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sidjabat HE, Silveira FP, Potoski BA, et al. Interspecies spread of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase gene in a single patient. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1736–8. doi: 10.1086/648077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rogers BA, Sidjabat HE, Paterson DL. Escherichia coli O25b-ST131: a pandemic, multiresistant, community-associated strain. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1–14. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peirano G, Pitout JD. Molecular epidemiology of Escherichia coli producing CTX-M β-lactamases: the worldwide emergence of clone ST131 O25:H4. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;35:316–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson JR, Urban C, Weissman SJ, et al. Molecular epidemiological analysis of Escherichia coli sequence type ST131 (O25:H4) and blaCTX-M-15 among extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing E. coli from the United States (2000–2009) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:2364–70. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05824-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris D, Boyle F, Ludden C, et al. Production of KPC-2 carbapenemase by an Escherichia coli clinical isolate belonging to the international ST131 clone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:4935–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05127-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naas T, Cuzon G, Gaillot O, Courcol R, Nordmann P. When carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase KPC meets Escherichia coli ST131 in France. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:4933–4. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00719-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson KF, Lonsway DR, Rasheed JK, et al. Evaluation of methods to identify the Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase in Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:2723–5. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00015-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doi Y, Potoski BA, Adams-Haduch JM, Sidjabat HE, Pasculle AW, Paterson DL. Simple disk-based method for detection of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-type β-lactamase by use of a boronic acid compound. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:4083–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01408-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-first informational supplement. Wayne, PA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sidjabat HE, Paterson DL, Qureshi ZA, et al. Clinical features and molecular epidemiology of CMY-type β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:739–44. doi: 10.1086/597037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sidjabat HE, Paterson DL, Adams-Haduch JM, et al. Molecular epidemiology of CTX-M-producing Escherichia coli isolates at a tertiary medical center in western Pennsylvania. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4733–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00533-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clermont O, Bonacorsi S, Bingen E. Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:4555–8. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.10.4555-4558.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wirth T, Falush D, Lan R, et al. Sex and virulence in Escherichia coli: an evolutionary perspective. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:1136–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ribot EM, Fair MA, Gautom R, et al. Standardization of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocols for the subtyping of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella, and Shigella for PulseNet. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2006;3:59–67. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2006.3.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doi Y, Paterson DL, Adams-Haduch JM, et al. Reduced susceptibility to cefepime among Escherichia coli clinical isolates producing novel variants of CMY-2 β-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3159–61. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00133-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson JR, Stell AL. Extended virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli strains from patients with urosepsis in relation to phylogeny and host compromise. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:261–72. doi: 10.1086/315217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coque TM, Novais A, Carattoli A, et al. Dissemination of clonally related Escherichia coli strains expressing extended-spectrum β-lactamase CTX-M-15. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:195–200. doi: 10.3201/eid1402.070350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Blanco J, Leflon-Guibout V, et al. Intercontinental emergence of Escherichia coli clone O25:H4-ST131 producing CTX-M-15. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:273–81. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mushtaq S, Irfan S, Sarma JB, et al. Phylogenetic diversity of Escherichia coli strains producing NDM-type carbapenemases. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2002–5. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cortes P, Blanc V, Mora A, et al. Isolation and characterization of potentially pathogenic antimicrobial-resistant Escherichia coli strains from chicken and pig farms in Spain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:2799–805. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02421-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naseer U, Haldorsen B, Tofteland S, et al. Molecular characterization of CTX-M-15-producing clinical isolates of Escherichia coli reveals the spread of multidrug-resistant ST131 (O25:H4) and ST964 (O102:H6) strains in Norway. Apmis. 2009;117:526–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2009.02465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oteo J, Diestra K, Juan C, et al. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in Spain belong to a large variety of multilocus sequence typing types, including ST10 complex/A, ST23 complex/A and ST131/B2. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;34:173–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoban DJ, Nicolle LE, Hawser S, Bouchillon S, Badal R. Antimicrobial susceptibility of global inpatient urinary tract isolates of Escherichia coli: results from the Study for Monitoring Antimicrobial Resistance Trends (SMART) program: 2009–2010. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;70:507–11. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2011.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pitout JD, Nordmann P, Laupland KB, Poirel L. Emergence of Enterobacteriaceae producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) in the community. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:52–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodriguez-Bano J, Paterson DL. A change in the epidemiology of infections due to extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing organisms. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:935–7. doi: 10.1086/500945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peirano G, Richardson D, Nigrin J, et al. High prevalence of ST131 isolates producing CTX-M-15 and CTX-M-14 among extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolates from Canada. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1327–30. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01338-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki S, Shibata N, Yamane K, Wachino J, Ito K, Arakawa Y. Change in the prevalence of extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in Japan by clonal spread. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63:72–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson JR, Johnston B, Clabots C, Kuskowski MA, Castanheira M. Escherichia coli sequence type ST131 as the major cause of serious multidrug-resistant E. coli infections in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:286–94. doi: 10.1086/653932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leflon-Guibout V, Blanco J, Amaqdouf K, Mora A, Guize L, Nicolas-Chanoine MH. Absence of CTX-M enzymes but high prevalence of clones, including clone ST131, among fecal Escherichia coli isolates from healthy subjects living in the area of Paris, France. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:3900–5. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00734-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goren MG, Carmeli Y, Schwaber MJ, Chmelnitsky I, Schechner V, Navon-Venezia S. Transfer of carbapenem-resistant plasmid from Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 to Escherichia coli in patient. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1014–7. doi: 10.3201/eid1606.091671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richter SN, Frasson I, Bergo C, Parisi S, Cavallaro A, Palu G. Transfer of KPC-2 carbapenemase from Klebsiella pneumoniae to Escherichia coli in a patient: first case in Europe. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2040–2. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00133-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bulik CC, Nicolau DP. In vivo efficacy of simulated human dosing regimens of prolonged-infusion doripenem against carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:4112–5. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00026-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.