Abstract

The 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11.2DS) is the most common microdeletion disorder and is characterized by abnormal development of the pharyngeal apparatus and heart. Cardiovascular malformations (CVMs) affecting the outflow tract (OFT) are frequently observed in 22q11.2DS and are among the most commonly occurring heart defects. The gene encoding T-box transcription factor 1 (Tbx1) has been identified as a major candidate for 22q11.2DS. However, CVMs are generally considered to have a multigenic basis and single-gene mutations underlying these malformations are rare. The T-box family members Tbx2 and Tbx3 are individually required in regulating aspects of OFT and pharyngeal development. Here, using expression and three-dimensional reconstruction analysis, we show that Tbx1 and Tbx2/Tbx3 are largely uniquely expressed but overlap in the caudal pharyngeal mesoderm during OFT development, suggesting potential combinatorial requirements. Cross-regulation between Tbx1 and Tbx2/Tbx3 was analyzed using mouse genetics and revealed that Tbx1 deficiency affects Tbx2 and Tbx3 expression in neural crest-derived cells and pharyngeal mesoderm, whereas Tbx2 and Tbx3 function redundantly upstream of Tbx1 and Hh ligand expression in pharyngeal endoderm and bone morphogenetic protein- and fibroblast growth factor-signaling in cardiac progenitors. Moreover, in vivo, we show that loss of two of the three genes results in severe pharyngeal hypoplasia and heart tube extension defects. These findings reveal an indispensable T-box gene network governing pharyngeal and OFT development and identify TBX2 and TBX3 as potential modifier genes of the cardiopharyngeal phenotypes found in TBX1-haploinsufficient 22q11.2DS patients.

INTRODUCTION

22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11.2DS) comprises DiGeorge syndrome, velocardiofacial syndrome and conotruncal anomaly face syndrome and is the most common interstitial microdeletion syndrome with an estimated prevalence of one per 4000 live births (1). 22q11.2DS patients exhibit a wide spectrum of developmental anomalies, including craniofacial defects, hypoplasia of the thymus and parathyroid glands, and conotruncal cardiovascular malformations (CVMs). CVMs are the leading cause of birth defect-related death in the western world (2,3). Defects in the formation of the arterial pole of the heart, or outflow tract (OFT), account for up to 30% of CVMs. Formation of the OFT is a complex process, requiring spatial and temporal expression of genes in multiple interacting cell types. A population of mesodermal progenitor cells called the second heart field (SHF) residing in splanchnic pharyngeal mesoderm in the dorsal wall of the pericardial cavity is progressively added to the elongating arterial pole of the embryonic heart tube giving rise to the right ventricle and OFT (4). These SHF cells are closely associated with neural crest (NC)-derived mesenchyme and pharyngeal endoderm, and complex autocrine and paracrine signaling events regulate SHF development, including pro-proliferative fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and Sonic hedgehog (Shh) signals and pro-differentiation bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signals (5–7). Direct or indirect perturbation of SHF development leads to failure of correct alignment between the great arteries and ventricles during cardiac septation resulting in conotruncal CVMs. However, the mechanisms coordinating intercellular signaling events during SHF deployment remain insufficiently understood.

While single-gene mutations or chromosomal abnormalities cause certain CVMs or syndromes, the majority of CVMs appear to have a multifactorial basis. Despite this, little is known about the networks of interacting genes that control cardiac or pharyngeal morphogenesis. Several scenarios involving interactions of multiple genes with major or minor effects have been proposed to explain the complex inheritance and variability of CVMs (8). T-box transcription factors play a series of critical roles in patterning and morphogenesis of the vertebrate heart (6,9). TBX1 is a major candidate gene in the etiology of 22q11.2DS, contributing to a variable phenotypic spectrum including conotruncal congenital heart defects (10). In mice, haploinsufficiency of Tbx1 causes fourth pharyngeal arch artery (PAA) defects, whereas Tbx1 null mutants display most of the severe defects found in 22q11.2DS patients, including common arterial trunk (11–13). Tbx1 is required in pharyngeal mesoderm to regulate proliferation and differentiation of SHF progenitor cells (7,14–17). This function is mediated in part by the regulation of FGF ligand expression and signal response (18,19). Other T-box proteins known to impact on OFT development are the closely related paralogs Tbx2 and Tbx3. Heterozygous mutations in TBX3 cause Ulnar-Mammary syndrome, but usually do not include heart defects (20). Nevertheless, mouse studies have shown that Tbx3 plays important roles in the development of the cardiac conduction system (21). Moreover, whereas Tbx3 haploinsufficiency does not affect heart development, Tbx3 loss-of-function results in OFT alignment defects including double outlet right ventricle (22,23). The role of Tbx3 in OFT development appears to be indirect as Tbx3 is predominantly expressed in cardiac NC cells and ventral pharyngeal endoderm, rather than pharyngeal mesoderm (22,23). The paralogous gene Tbx2 is expressed in pharyngeal mesoderm, including the SHF and OFT, and in NC-derived cells. Although Tbx2-haploinsufficient mice appear normal, a fraction of Tbx2 null embryos develop OFT alignment defects (24,25).

Here, we show that Tbx2 and Tbx3 are required redundantly during OFT development to attenuate Tbx1 expression in the ventral foregut, but also depend on Tbx1 for their correct distribution in pharyngeal mesoderm, endoderm and NC cells. Furthermore, loss-of-function of Tbx1 and either Tbx2 or Tbx3 also causes severe defects during OFT and foregut development, suggesting that these three genes (Tbx1/Tbx2/Tbx3) comprise a crucial regulatory network controlling the topography of intercellular signaling during pharyngeal and OFT development. When disrupted, this network fails to properly orchestrate morphogenesis of the pharyngeal apparatus and cardiovascular system. Our results underscore the clinical relevance of this Tbx1/Tbx2/Tbx3 network, which potentially contributes to the phenotypic variation of congenital cardiopharyngeal malformations in the 22q11.2DS patient population.

RESULTS

Three-dimensional analysis of Tbx1, Tbx2 and Tbx3 transcript distribution in the cardiopharyngeal region

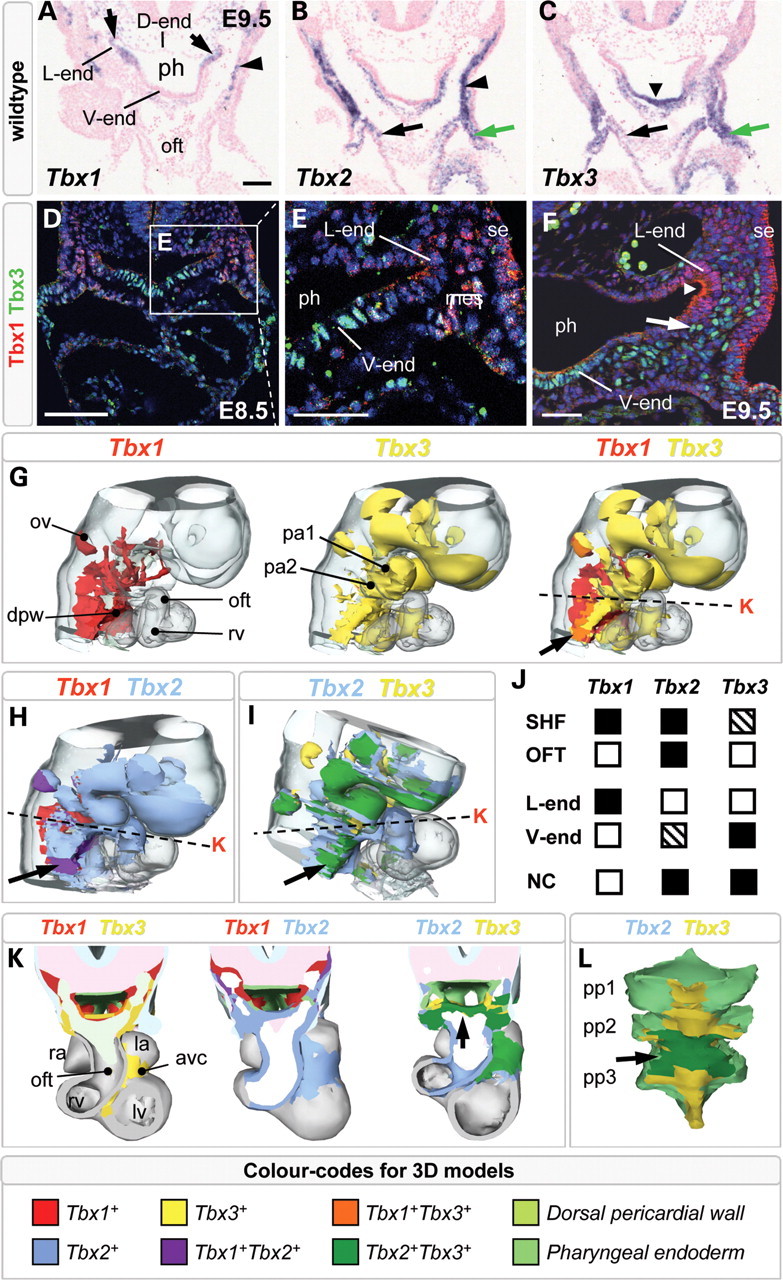

In order to understand the multigenic cause of cardiopharyngeal defects observed in 22q11.2DS, we first explored whether Tbx1, Tbx2 and Tbx3 could be expected to function co-operatively during arterial pole development. This was achieved by examining their expression patterns relative to each other by in situ hybridization (ISH) (Fig. 1A–C) and fluorescent immunohistochemistry (IHC) (Fig. 1D–F) in wild-type embryonic day (E) 8.5 and E9.5 embryos, stages at which SHF cells are added to the elongating heart tube. To facilitate a more accurate identification of unique and overlapping expression sites in the cardiopharyngeal region, we generated three-dimensional reconstructions of transcript distributions for these three genes (Fig. 1G–L; Supplementary Material, Fig. S1 and interactive 3D image). At E8.5 and E9.5, Tbx1 is expressed in the lateral pharyngeal endoderm (arrows and arrowheads in Fig. 1A and F, respectively) and surrounding mesoderm, in the SHF and in the surface ectoderm (Fig. 1D–F). In pharyngeal endoderm, Tbx3 primarily accumulates ventrally (Fig. 1C, arrowhead and Fig. 1D–F), overlapping with Tbx2 in the endoderm underlying the aortic sac (Fig. 1K and L, arrow). Tbx2 and Tbx3 are also co-expressed in the NC-derived mesenchyme (Fig. 1B and C, black arrow; Fig. 1I, arrow) and the dorsal and lateral pericardial wall at E9.5 (Fig. 1B and C, green arrow). Overlap between Tbx1 and Tbx2 was observed in the mesoderm lateral to and in the underlying ventral pharyngeal endoderm (Fig. 1A and B, arrowhead), including SHF cells. A small patch of overlapping Tbx1 and Tbx3 expression was also observed in the dorsal pericardial wall (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2 and 3D image). Unlike Tbx1 and Tbx3, Tbx2 is robustly expressed in the myocardial wall of the developing OFT at E9.5 (Fig. 1G and I). Tbx2 and Tbx3 are co-expressed in the distal OFT mesenchyme at this stage (Fig. 1B, C and K). In summary, Tbx2 and Tbx3 are extensively co-expressed, whereas Tbx1 demonstrates a more distinct pattern in the pharyngeal mesoderm and endoderm (Fig. 1J).

Figure 1.

Unique and overlapping expression patterns of Tbx1, Tbx2 and Tbx3. In situ hybridization at E9.5 showing Tbx1 (A), Tbx2 (B) and Tbx3 (C) mRNA in pharyngeal endoderm (A, arrows; C, arrowhead), neural crest-derived mesenchyme (B, C, black arrow) and pharyngeal mesoderm (A, B, arrowheads; B, C, green arrows). At E8.5 (D, E) and E9.5 (F), Tbx1 protein (red) was found in lateral pharyngeal endoderm (L-end, arrowhead), pharyngeal mesoderm (mes) and surface ectoderm (se) and Tbx3 protein (green) in ventral pharyngeal endoderm (V-end) and neural crest-derived mesenchyme (arrow). Three-dimensional reconstructions showing unique and overlapping (black arrow) sites of expression of Tbx1/Tbx3 (G), Tbx1/Tbx2 (H) and Tbx2/Tbx3 (I). (J) Summary of expression sites of Tbx1–2–3 at E8.5–9.5. Note that ventral endodermal Tbx2 expression is restricted to where endoderm underlies the aortic sac. Cross sections (K) of corresponding three-dimensional models (G, H, I, dashed line). Note the overlap between Tbx2 and Tbx3 in ventral endoderm (L, arrow). avc, atrioventricular canal; dpw, dorsal pericardial wall; la, left atrium; lv, left ventricle; oft, outflow tract; ov, otic vesicle; pa1, 2, 1st and 2nd pharyngeal arch; ph, pharynx; pp1–3, first, second and third pharyngeal pouches; ra, right atrium; rv, right ventricle. Scale bar in (A) and (D) is 100 μm and in (E) and (F) is 50 μm.

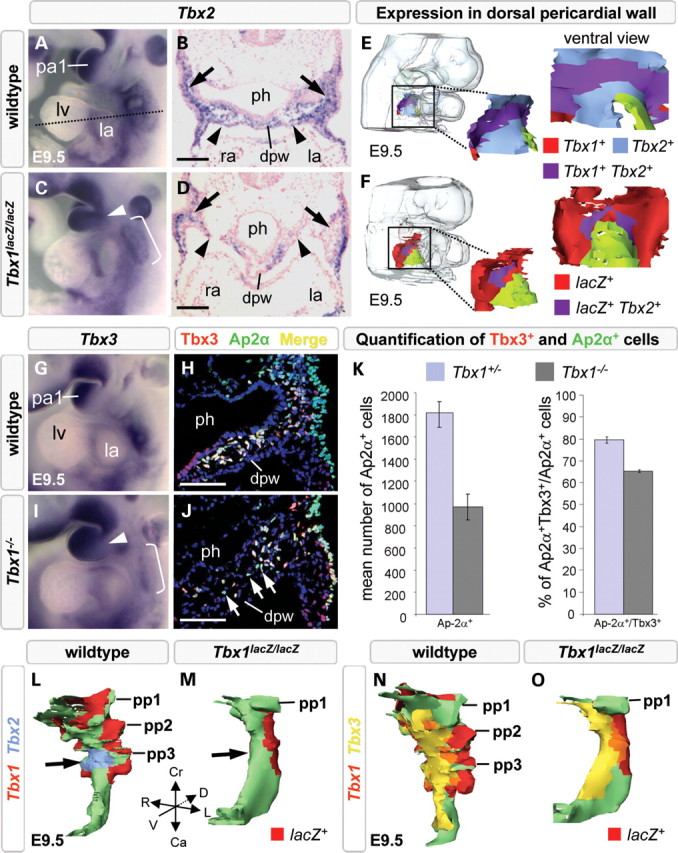

Loss of Tbx1 affects Tbx2 and Tbx3 expression in the caudal pharynx

SHF signaling pathways are affected in Tbx1 null-mutant embryos resulting in hypoplasia of the distal OFT at mid-gestation (26). To determine whether this OFT phenotype coincides with altered expression of Tbx2 and Tbx3, we examined the expression patterns of all three genes by ISH on whole embryos and transverse sections in wild-type and Tbx1−/− embryos. The level of Tbx2 expression was reduced in the pharyngeal region in E9.5 Tbx1−/− embryos (Fig. 2C and D) compared with controls (Fig. 2A and B). In contrast, the expression domain of Tbx2 was expanded in the first arch of Tbx1 null embryos (Fig. 2C, arrowhead) (27). Tbx2 was downregulated in the dorsal pericardial wall (Fig. 2F, red surface), and the area of co-expression with Tbx1 in the SHF was thus greatly reduced in size (purple surface in Fig. 2F). Similarly, accumulation of Tbx3 transcripts was reduced in the caudal pharyngeal region including the dorsal pericardial wall (Fig. 2I, bracket; Supplementary Material, Fig. S2B and D), and expanded in the first arch of Tbx1−/− embryos at E9.5 (Fig. 2I, arrowhead).

Figure 2.

Tbx2 and Tbx3 are affected by loss of Tbx1. Tbx2 and Tbx3 expression is broader in the first arch (arrowhead in C and I) and reduced in the caudal pharynx (brackets in C and I; arrows in D and J) of E9.5 Tbx1 null embryos. Three-dimensional reconstructions of the dorsal pericardial wall showed a smaller overlapping region of Tbx1/Tbx2 (compare purple region in E with F) and reduced detection of Tbx2 mRNA (D, arrowheads, blue region absent in F) in the dorsal pericardial wall of Tbx1−/− embryos. Immunofluorescence and histograms (K) showing a reduction in Tbx3-positive mesenchymal cells (J, white arrows), Ap2α-positive neural crest-derived cells (K) and Tbx3-positive/Ap2α-positive cells (compare yellow staining in H with J; K) in Tbx1−/− embryos. Three-dimensional reconstructions reveal loss of Tbx2 expression in ventral pharyngeal endoderm (M, arrow), whereas expression of Tbx3 is maintained in pharyngeal endoderm of Tbx1−/− embryos (O, yellow). Ca, caudal; Cr, cranial; D, dorsal; dpw, dorsal pericardial wall; L, left lateral; la, left atrium; lv, left ventricle; pa1, first pharyngeal arch; ph, pharynx; pp1–3; first, second and third pharyngeal pouch; R, right lateral; ra, right atrium; V, ventral. Scale bar is 100 μm.

Previous work has documented reduced NC-derived cell numbers in the caudal pharyngeal region of Tbx1 null mutants, showing that Tbx1-responsive Gbx2 signaling from pharyngeal ectoderm is required for proper guidance of the adjacently located NC cells to the caudal pharynx, where Tbx2 and Tbx3 are co-expressed (28,29). We thus analyzed and quantified the number of NC-derived cells in wild-type and Tbx1 null-mutant embryos by labeling NC-derived cells with an Ap2α antibody, and found a 50% reduction in the number of Ap2α-positive NC-derived cells and, among the remaining cells, a 20% reduction of the fraction of Tbx3-positive cells compared with the wild-type situation (n= 3 embryos of each genotype; Fig. 2H, J, K). Hence, loss of Tbx3 expression in Tbx1−/− embryos reflects both reduced numbers of crest-derived cells and a reduction of Tbx2- and Tbx3-positive crest cells. In wild-type embryos, Tbx2 and Tbx3 overlap in ventral pharyngeal endoderm. In the hypoplastic foregut of Tbx1−/− embryos, we observed that ventral expression of Tbx2 was decreased (Fig. 2M, arrow), whereas Tbx3 expression was maintained (Fig. 2O). Thus, Tbx1-deficiency affects Tbx2 and Tbx3 expression in mesodermal, NC-derived and endodermal cells in the caudal pharynx, supporting a requirement for Tbx1 upstream of Tbx2 and Tbx3 during OFT development.

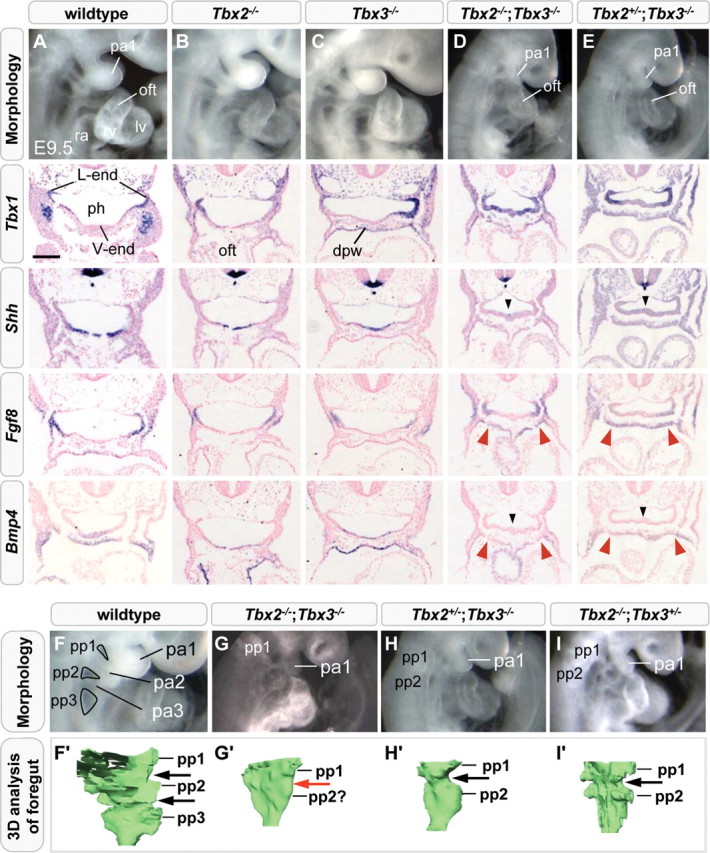

Compound Tbx2 andTbx3-deficiency affects endodermal Tbx1 expression and key signaling molecules in the SHF

We next assessed whether Tbx1 expression is affected in the absence of paralogs Tbx2 or Tbx3 by analyzing E9.5 Tbx2−/− and Tbx3−/− mouse embryos using ISH on transverse sections. The overall expression pattern of Tbx1 was found to be normal in both Tbx2 and Tbx3 null mutants (Fig. 3, Tbx1). Because Tbx2 and Tbx3 are co-expressed in multiple regions and share common targets in the heart, they could function redundantly to regulate Tbx1 and OFT development (9). We thus generated mice double heterozygous for Tbx2 and Tbx3 null alleles. Only a few such mice were obtained because this genotype is afflicted with severe craniofacial defects (30). Tbx2;Tbx3 double-heterozygous mice were interbred to obtain Tbx2−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos (Table 1). Tbx2−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos could be recovered up to E9.5 (n= 11/150) at Mendelian ratios and displayed impaired overall embryonic growth, pericardial edema, and hypoplasia of the OFT and right ventricle (Fig. 3D; Supplementary Material, Fig. S3C and D). Tbx1 expression is restricted to lateral pharyngeal endoderm in wild-type, Tbx2−/− and Tbx3−/− embryos. In Tbx2−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos, Tbx1 was upregulated in the subdomain of the ventral endoderm that normally co-expresses Tbx2 and Tbx3 (Fig. 3, Tbx1, arrowhead; Supplementary Material, Fig. S3L, arrow; Fig. 1L, arrow). In contrast, Tbx1 expression was unchanged in pharyngeal mesoderm and in lateral pharyngeal endoderm that do not co-express these factors. This observation suggests functional redundancy of Tbx2 and Tbx3 in the suppression of Tbx1 expression in ventral pharyngeal endoderm.

Figure 3.

Morphological, Tbx1 expression and signaling component analysis in Tbx2;Tbx3 compound mutant embryos. Severe hypoplasia of the outflow tract and right ventricle, ectopic distribution of Tbx1 mRNA and decreased expression of Bmp4 and Shh in the ventral endoderm (black arrowheads) were observed in E9.5 Tbx2−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos compared with wild-type, Tbx2−/− and Tbx3−/− embryos (A–D). Elevated Fgf8 and decreased Bmp4 expression was observed in splanchnic mesoderm (red arrowheads). Tbx2+/−;Tbx3−/− and Tbx2−/−;Tbx3+/− embryos display similar aberrations in transcript levels of Shh, Fgf8 and Bmp4, but no ventral expansion of endodermal Tbx1 (E). Composite Tbx2;Tbx3 mutant embryos with pharyngeal arch, OFT and RV hypoplasia (G–I). Morphology and three-dimensional reconstruction of the pharyngeal endoderm showing patterning defects of interpouch endoderm in Tbx2−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos (G′, red arrow) and hypoplasia of the first and second pharyngeal pouches (G′-I′). dpw, dorsal pericardial wall; lv, left ventricle; pa1–3, first, second and third pharyngeal arch; oft, outflow tract; ph, pharynx; pp1–3; first, second and third pharyngeal pouch; ra, right atrium; rv, right ventricle. Scale bar in (A) is 100 μm.

Table 1.

Phenotypic severity of embryos resulting from Tbx2+/−;Tbx3+/−, Tbx1+/−;Tbx2+/− or Tbx1+/−;Tbx3+/− intercrosses

| Genotype | na | n (exp)b | Phenotypic severityc |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| Tbx2+/+;Tbx3+/+ | 10 | 9.4 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tbx2+/−;Tbx3+/+ | 20 | 18.8 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tbx2−/−;Tbx3+/+ | 7 | 9.4 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Tbx2+/+;Tbx3+/− | 20 | 18.8 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tbx2+/−;Tbx3+/− | 34 | 37.5 | 34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tbx2−/−;Tbx3+/− | 21 | 18.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 2 |

| Tbx2+/+;Tbx3−/− | 12 | 9.4 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Tbx2+/−;Tbx3−/− | 15 | 18.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 5 |

| Tbx2−/−;Tbx3−/− | 11 | 9.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| Total | 150 | 100 | 0 | 3 | 27 | 20 | |

| Tbx1+/+;Tbx2+/+ | 10 | 8.4 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tbx1+/−;Tbx2+/+ | 24 | 17 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tbx1−/−;Tbx2+/+ | 7 | 8.4 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tbx1+/+;Tbx2+/− | 16 | 17 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tbx1+/−;Tbx2+/− | 36 | 34 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tbx1−/−;Tbx2+/− | 13 | 17 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tbx1+/+;Tbx2−/− | 7 | 8.4 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Tbx1+/−;Tbx2−/− | 17 | 17 | 15 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Tbx1−/−;Tbx2−/− | 4d | 8.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Total | 134 | 107 | 20 | 3 | 0 | 4 | |

| Tbx1+/+;Tbx3+/+ | 13 | 9.75 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tbx1+/−;Tbx3+/+ | 17 | 19.5 | 16 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tbx1−/−;Tbx3+/+ | 7 | 9.75 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tbx1+/+;Tbx3+/− | 19 | 19.5 | 17 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Tbx1+/−;Tbx3+/− | 34 | 39 | 29 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Tbx1−/−;Tbx3+/− | 26 | 19.5 | 0 | 23 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Tbx1+/+;Tbx3−/− | 12 | 9.75 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| Tbx1+/−;Tbx3−/− | 16 | 19.5 | 2 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 1 |

| Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− | 12 | 9.75 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

| Total | 156 | 62 | 65 | 15 | 4 | 10 | |

aNumber of embryos of each genotype collected between E9.0 and E10.5.

bNumber of embryos expected (exp) of each genotype.

cPhenotypic severity was determined according to the following criteria: 1: wild-type configuration (e.g. Fig. 3A), 2: arches 2–6 absent, distal outflow tract hypoplastic (e.g. Fig. 4B), 3: right ventricle and outflow tract hypoplastic (e.g. Fig. 3G), 4: pharyngeal hypoplasia and severe right ventricular and outflow tract hypoplasia (e.g. Fig. 3D), 5: C-looped dilated heart tube, edema, pharyngeal hypoplasia (including arch 1) (e.g. Fig. 4D).

dOf which three embryos were necrotic.

The LIM homeodomain transcription factor Isl1 is expressed in undifferentiated cardiac progenitors in the SHF and in the distal OFT. In Tbx2−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos, Isl1 transcripts could still be detected in SHF cells and in the shortened OFT, suggesting that the deployment of SHF cells is compromised downstream of Isl1 expression (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3D, arrow). We therefore examined the expression patterns of known regulators of SHF development. Shh has been implicated in proliferation and deployment of cardiac progenitor cells and in signaling events required for cardiac NC survival from an expression site in ventral pharyngeal endoderm (31). Moreover, Shh has been reported to regulate Tbx1 in pharyngeal endoderm and arches (32,33). Shh expression in ventral pharyngeal endoderm was decreased, concomitant with the increased expression of Tbx1, in Tbx2−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos, but not in Tbx2 or Tbx3 single mutants (Fig. 3, Shh, arrowhead).

We subsequently investigated FGF signaling, also known to play a critical role in regulating SHF progenitor cell proliferation in pharyngeal mesoderm distal to the OFT. Fgf8 appears to be the major FGF ligand driving heart tube elongation and Fgf8 and Tbx1 have been linked genetically during vascular morphogenesis and to the etiology of 22q11.2DS (6,18,34,35). At E9.5, Fgf8 is co-expressed with Tbx1 in lateral pharyngeal endoderm, overlying surface ectoderm and, at a low level, in pharyngeal mesoderm lateral to the pharynx including SHF progenitor cells (15,36,37). We found elevated Fgf8 transcript accumulation in the SHF and OFT of compound Tbx2−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos (Fig. 3, Fgf8, red arrowheads; Supplementary Material, Fig. S3K, arrowhead).

BMP signaling induces cardiac differentiation and antagonizes FGF signaling proximally to the OFT during heart tube extension (7). We therefore included Bmp4, known to be a crucial BMP ligand during OFT development, in our expression pattern analyses (38). We observed a decrease in Bmp4 transcript levels in ventral pharyngeal endoderm, where Tbx2 and Tbx3 are normally co-expressed, as well as in pharyngeal mesoderm including the SHF and distal OFT of Tbx2−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos (Fig. 3, Bmp4, arrowheads). Bmp4 and Nkx2–5 expression in the dorsal pericardial wall has been reported to depend on GATA family member Gata6, where it is required for proper maturation of cardiomyocyte precursors (39). In Tbx2−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos, ISH revealed a decrease in Gata6 expression in the dorsal pericardial wall, presumably affecting BMP-signaling in the SHF (data not shown). Albeit slightly less severe, a shortened OFT, hypoplastic right ventricle and modulations in FGF and BMP ligand and Shh expression were also observed in Tbx2−/−;Tbx3+/− and Tbx2+/−;Tbx3−/− compound mutants (Fig. 3E and I; n= 21 and n= 15, respectively, Table 1; n= 3 as examined by ISH). However, endodermal expression of Tbx1 was unaffected in these compound mutant embryos (Fig. 3E, Tbx1). These results indicate gene dosage effects and functional redundancy between Tbx2 and Tbx3, as a single allele of either gene is insufficient to activate normal FGF and BMP and Hh signaling pathways, yet is sufficient to repress Tbx1 in ventral endoderm.

Taken together, our findings indicate that endodermal Tbx1 and the abovementioned signaling molecules are potential downstream effectors of the redundant actions of Tbx2 and Tbx3, impacting on both pharyngeal and OFT development.

Pharyngeal segmentation defects in Tbx2−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos

In vertebrates, the pharyngeal apparatus is a transient structure and gives rise to the thymus, thyroid and parathyroid, structures frequently affected in 22q11.2DS. Upon macroscopic examination of Tbx2−/−;Tbx3−/−, Tbx2−/−;Tbx3+/− and Tbx2+/−;Tbx3−/− mutants at E9.5, the pharyngeal region was observed to be severely affected (Table 1) revealing an underdeveloped first pharyngeal arch, while the more caudal arches were hypoplastic when compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 3G–I). The foregut of E9.5 control embryos showed three pharyngeal pouches and two interpouch regions (Fig. 3F and F′, pp1-3). Tbx2−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos displayed some pharyngeal expansion, as the foregut did not acquire the tube-like shape observed in Tbx1−/− embryos (compare Fig. 3G′ with 2M and O). However, interpouch endoderm could not be distinguished (Fig. 3G′, red arrow). Pharyngeal segmentation was also, albeit less severely, affected in embryos lacking three of the four alleles (Tbx2+/−;Tbx3−/− and Tbx2−/−;Tbx3+/−), indicating that a developmental delay is not the primary cause of this phenotype (Fig. 3H and I). Unfortunately, all compound Tbx2;Tbx3 mutants die by mid-gestation, making it impossible to study the development and differentiation of pharyngeal precursors of the (para)thyroid and thymus. Nevertheless, our results indicate that proper segmentation of the pharyngeal region requires all four alleles of Tbx2 and Tbx3, suggesting roles during development of the pharyngeal apparatus and possibly its derivatives.

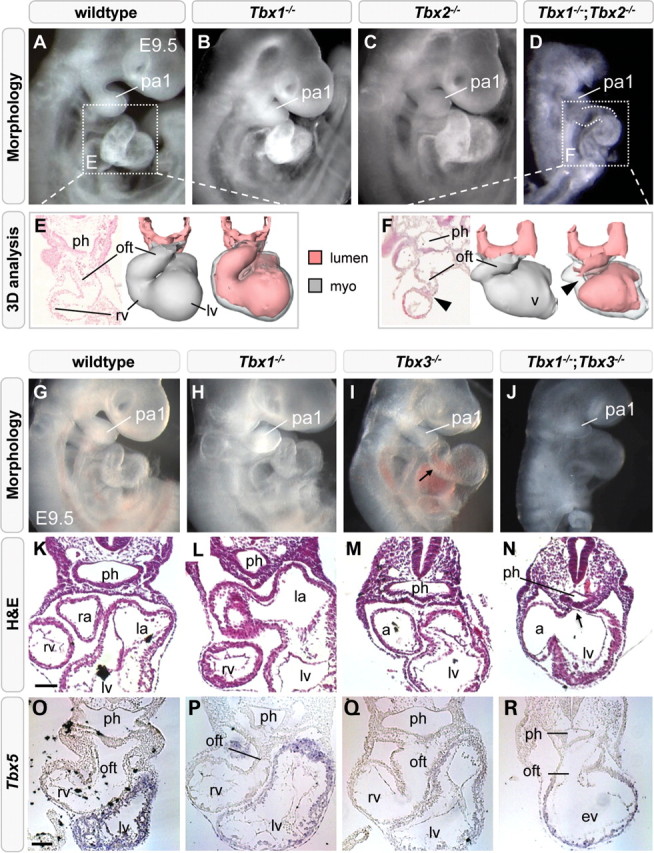

Severe arterial pole defects and altered FGF- and BMP-signaling in Tbx1−/−;Tbx2−/− and Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos

Since Tbx1 is required for correct pharyngeal expression of Tbx2 and Tbx3, which in turn are redundantly required to attenuate expression of Tbx1 in the ventral endoderm, we hypothesized that these three genes could constitute a regulatory T-box network. We therefore investigated the combinatorial in vivo requirements for Tbx1 and either Tbx2 or Tbx3 by interbreeding Tbx1;Tbx2 or Tbx1;Tbx3 double-heterozygous mice and analyzing the respective compound mutant embryos. Tbx1+/−;Tbx2+/− and Tbx1+/−;Tbx3+/− mice were obtained at the expected Mendelian ratio and are viable and fertile. As Tbx3-deficiency is reported to delay aortic arch artery formation (23), we investigated whether heterozygosity for Tbx3 influences the incidence or severity of PAA defects in Tbx1+/− embryos. We did not find significant changes at either E10.5 or E15.5 (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4D). Analysis of E9.5 and E10.5 embryos obtained by interbreeding Tbx1+/−;Tbx2+/− or Tbx1+/−;Tbx3+/− mice revealed that Tbx1−/−;Tbx2−/− embryos were not recovered at the expected Mendelian ratio (n= 4/134, expected n= 8.4/134), in contrast to Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos (12/156). Importantly, all four of Tbx1−/−;Tbx2−/− embryos and nine of 12 (75%) of Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos displayed impaired overall embryonic growth with development apparently blocked at E8.5 (Fig. 4D and J). All these embryos exhibited pericardial edema. Severe hypoplasia of the pharyngeal region was also observed, including underdevelopment of the first arch (Fig. 4D and J), which forms relatively normally in Tbx1−/− embryos (11). Expansion and segmentation of the pharyngeal endoderm was mildly affected in Tbx1+/−;Tbx2−/− embryos compared with wild-type and Tbx1−/− embryos (Supplementary Material, Fig. S5C). We could not perform transcript detection or immunohistochemical analyses on Tbx1−/−;Tbx2−/− embryos, since three out of four embryos were necrotic and thus unfit for molecular analysis. We compared cardiac morphology between E9.5 wild-type and Tbx1−/−;Tbx2−/− embryos using histological and three-dimensional analyses and found a severely shortened OFT connected to an embryonic ventricle, whereas morphological signs of a developing right ventricle were lacking (Fig. 4D and F, n= 3). Moreover, the OFT lumen of the mutant heart was extremely narrow or completely obstructed by myocardium.

Figure 4.

Heart tube elongation is severely compromised by loss of Tbx1 and either Tbx2 or Tbx3. Right lateral views at E9.5 showing pharyngeal and cardiac hypoplasia in Tbx1−/−;Tbx2−/− (D) and Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos (J). Three-dimensional reconstruction of a Tbx1−/−;Tbx2−/− heart revealing a shortened outflow tract with a constricted lumen (F, arrowhead). Transverse sections showing pharyngeal hypoplasia (ph) and a persistent dorsal mesocardium in Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos (N, arrow). Milder pharyngeal hypoplasia is observed in Tbx1−/− embryos (L). In situ hybridization showing reduced Tbx5-negative right ventricular and OFT myocardium in Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos (R). lv, left ventricle; la, left atrium, pa1, first pharyngeal arch; oft, outflow tract; ph, pharynx; ra, right atrium; rv, right ventricle. Scale bar is 100 μm.

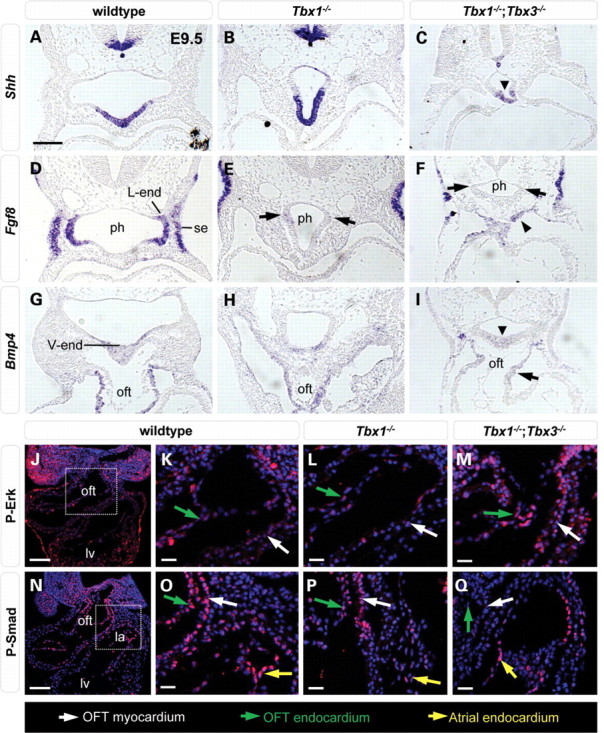

Since we could not isolate a sufficient number of Tbx1−/−;Tbx2−/− embryos, we examined transverse sections of Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos, and found that pharyngeal endoderm was severely reduced, and that the dorsal mesocardium failed to close under the hypoplastic pharynx (Fig. 4N, arrow). Gene-expression analysis revealed that Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− hearts were almost entirely positive for Tbx5 transcripts, normally restricted to the left ventricle and inflow regions of the heart (Fig. 4O–R). In addition, very few Isl1-positive cells were observed at the arterial pole compared with the situation in Tbx1−/− or the majority of Tbx3−/− hearts (Supplementary Material, Fig. S6A–D). The observation that Tbx2 and Tbx3 are co-operatively required for Hh, FGF and BMP ligand expression, key regulators of cardiac progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation led us to investigate the extent to which these signaling pathways were altered in Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos compared with wild-type, Tbx1−/− and Tbx3−/− embryos. Using ISH on transverse sections, Shh expression was found to be expressed at a lower level in ventral pharyngeal endoderm of Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− (Fig. 5C) compared with Tbx1−/− (Fig. 5B) and Tbx3−/− embryos (Fig. 3, Shh). Fgf8 expression was reduced in lateral pharyngeal endoderm of Tbx1−/− embryos at E9.5, as previously documented (Fig. 5E, arrow) (28). Additionally, in Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− compound mutants, Fgf8 transcript accumulation was elevated in the SHF and OFT (Fig. 5F, arrowhead). Consistent with elevated ventral and loss of lateral Fgf8 expression, increased p-ERK was observed in pharyngeal mesoderm underlying the pharynx and in the distal OFT of Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos (Fig. 5M, white arrow), compared with wild-type and Tbx1−/− embryos (Fig. 5K and L). Bmp4 expression was unchanged in Tbx1−/− embryos (compare Fig. 5G with H), but decreased transcript levels were observed in the distal OFT and SHF of Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos (Fig. 5I). Consistent with altered Bmp4 expression, reduced P-Smad labeling was observed in the distal OFT of Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− (Fig. 5Q, white arrow) compared with wild-type and Tbx1−/− embryos (Fig. 5O and P).

Figure 5.

Altered signaling pathway components in Tbx1;Tbx3 composite mutant embryos. In situ hybridization showing that endodermal Shh expression was reduced in E9.5 Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− compared with wild-type and Tbx1−/− embryos (A–C, arrowhead). Fgf8 expression was reduced in lateral endoderm of Tbx1−/− (E, black arrows) and Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− (F, black arrows) embryos and elevated in ventral pharyngeal mesoderm of Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos (F, arrowhead). Bmp4 transcript detection was decreased in the distal OFT (I, arrowhead) of Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos. Immunofluorescence of wild-type P-Erk (J) and P-Smad (N) staining with higher magnifications in wild-type (K, O), Tbx1−/− (L, P) and Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos (M, Q) of the boxed regions in (J) and (N). P-Erk was increased (M, white arrow) and P-Smad was reduced (Q, white arrow) compared with the situation in atrial endocardium (Q, yellow arrow) in the distal OFT of Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos. ph, pharynx; l-end, lateral pharyngeal endoderm; lv, left ventricle; oft, outflow tract; v-end, ventral pharyngeal endoderm; se, surface ectoderm. Scale bar in (A), (J) and (N) is 100 μm and in (K–M), (O–Q) is 25 μm.

It has been shown that Tbx1 deficiency affects proliferation and differentiation of cardiac progenitor cells (17). Our results demonstrate that combinatorial loss of regulators of proliferation and differentiation of cardiac precursors in Tbx1−/−;Tbx2−/− and Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos results in a severe failure of heart tube elongation. These changes are similar to those observed in Tbx2−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos. Together, these data uncover impaired intercellular signaling in cardiac precursors and surrounding tissues in composite Tbx1/Tbx2/Tbx3 mutant embryos during OFT formation and pharyngeal development, structures contributing to the pathogenesis of 22q11.2DS.

DISCUSSION

Tbx1, Tbx2 and Tbx3 constitute a T-box regulatory network that controls OFT and pharyngeal development

Variability in clinical features between 22q11.2DS patients suggests that disruptions of multiple genes or pathways are likely to contribute to the cardiopharyngeal phenotypes found in 22q11.2DS. The 22q11.2DS gene Tbx1 is an important regulator of pharyngeal and OFT development, as Tbx1 deficiency affects SHF proliferation and differentiation leading to hypoplasia of the distal OFT and a common ventricular outlet, as well as patterning defects of the pharyngeal apparatus (11–13). As T-box factors comprise a family of related proteins that recognize a similar DNA-binding site and interact with the common co-factors (40), mutations in other T-box factor genes may contribute to phenotypic variability. Loss-of-function mouse models of two other T-box transcription factors, Tbx2 and Tbx3, revealed important roles during arterial pole development. Tbx2 and Tbx3 are closely related transcriptional repressors and are required for proper deployment of SHF cells and ventriculoarterial alignment (22–24,41). Tbx2 and Tbx3 are thus excellent candidate modifier genes of the cardiopharyngeal phenotypes resulting from Tbx1 disruption.

Our study indicates that Tbx1, Tbx2 and Tbx3 constitute a T-box regulatory network that controls OFT and pharyngeal development. Firstly, Tbx1 is required for the expression of Tbx2 and Tbx3 in pharyngeal and NC-derived mesenchyme. As Tbx1 is not expressed in NC cells, the effect on Tbx2 and Tbx3 in this cell type is likely to be indirect, mediated by altered intercellular signaling between Tbx1-expressing mesoderm or pharyngeal epithelia and NC cells. Tbx2 and Tbx3 are also potential direct targets of Tbx1, as these genes are co-expressed in pharyngeal mesoderm, including SHF cells in the dorsal pericardial wall. Ongoing analysis of Tbx2 and Tbx3 cis-regulatory elements will provide insight into the Tbx1-dependent signaling pathways, and potential direct role of Tbx1 in pharyngeal mesoderm, in the transcriptional regulation of these genes.

Secondly, we demonstrate that Tbx2 and Tbx3 are co-expressed in multiple cell populations and that loss-of-function of both Tbx2 and Tbx3 causes overall growth impairment, disturbed patterning of endodermal pouches (Fig. 3) and hypoplasia of the OFT and right ventricle suggesting defective SHF deployment. Tbx2 and Tbx3 overlap in function to pattern pharyngeal endoderm, since Tbx1 expression was observed in ventral pharyngeal endoderm of Tbx2−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos. This localized up-regulation of Tbx1 in the ventral endoderm of Tbx2;Tbx3 compound mutants, coinciding with the site where Tbx2 and Tbx3 are normally co-expressed, suggests that Tbx2 and Tbx3 directly suppress Tbx1 in this domain of the foregut. However, putative T-box binding sites regulating Tbx1 expression have not yet been identified. In addition, downregulation of Shh expression was observed in ventral pharyngeal endoderm where Tbx2 and Tbx3 are co-expressed. Hh signaling is required during SHF proliferation and migration and, together with downregulation of Bmp4 and upregulation of Fgf8 in the SHF and distal OFT, potentially underlies perturbed SHF deployment in Tbx2;Tbx3 compound mutants.

Thirdly, we provide evidence for the functional importance of a cross-regulating Tbx1/Tbx2/Tbx3 network, as embryos lacking Tbx1/Tbx2 or Tbx1/Tbx3 present similar severe pharyngeal and heart tube elongation phenotypes, suggesting overlapping roles for Tbx2 and Tbx3 in conferring network robustness. This phenotype is characterized by a C-looped heart tube that fails to close dorsally, cardiac dilation and OFT obstruction and pericardial edema, associated with reduced addition of SHF-derived progenitor cells to the arterial pole of the heart as revealed by Tbx5 and Isl1 expression. This severe phenotype is associated with overall growth impairment and developmental delay, potentially resulting from the cardiac defects. These results demonstrate that the Tbx1/Tbx2/Tbx3 network identified here is robust, requiring loss of function of two of the three components for network collapse and a severe phenotype to emerge. Tbx1 and Tbx2 are co-localized in a broader domain of the SHF than Tbx1 and Tbx3 potentially explaining the low numbers of Tbx1−/−;Tbx2−/− embryos recovered at E9.5. Moreover, downregulation of Tbx2 and Tbx3 in Tbx1-deficient endoderm and splanchnic mesoderm could further disrupt SHF development in Tbx1−/−;Tbx2−/− and Tbx1−/−;Tbx3−/− embryos.

Disruption of SHF signaling in compound T-box factor mutants

Recent work has defined the importance of intercellular signals in controlling SHF deployment during heart tube elongation, including FGF, BMP, Shh, Notch, retinoic acid and Wnt signaling pathways (5,6). In particular, the balance between FGF signaling, predominant in the lateral pharynx where it promotes progenitor cell proliferation, and BMP signaling, predominant in the ventral pharynx and distal OFT where it drives myocardial differentiation, has emerged as a central axis controlling progressive addition of SHF cells to the OFT. Antagonism between these signaling pathways has been dissected revealing that BMP signaling downregulates FGF signaling through BMP target genes in NC cells (7,42). In addition, BMP regulates microRNA function to silence the SHF progenitor cell genetic program (43). We have investigated the expression of Fgf8 and Bmp4, thought to be the major ligands mediating this signal exchange during OFT morphogenesis in the mouse, and p-Erk and P-Smad, intracellular readouts of FGF and BMP signaling, in embryos lacking combinations of Tbx1/Tbx2/Tbx3. Our results reveal that in compound mutant embryos, but not in single mutant embryos, combinatorial defects are observed such that proximal to the elongating heart tube, FGF signaling is elevated and BMP signaling is downregulated (Fig. 6). The topography of signaling events in the caudal pharynx of compound mutant embryos is thus altered and is likely to contribute significantly to generating the observed phenotypes.

Figure 6.

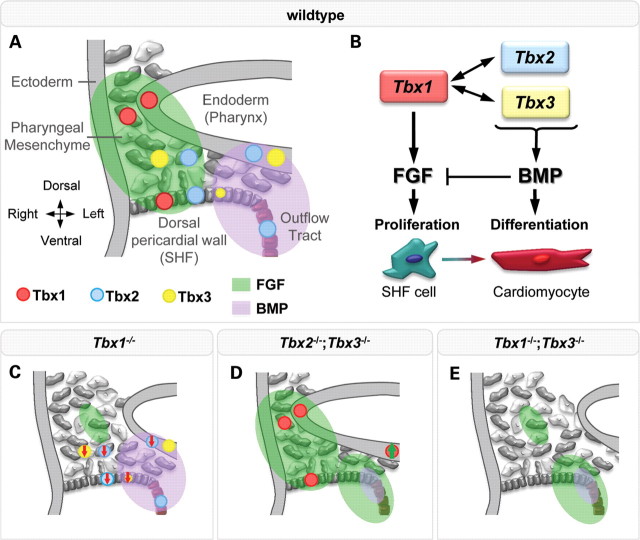

Altered FGF and BMP signaling in Tbx1/Tbx2/Tbx3 composite mutant embryos. Cartoons showing the distribution of Tbx1, Tbx2 and Tbx3 and the topography of BMP and FGF signaling in pharyngeal mesenchyme (composed of mesodermal cells, dark grey and neural crest-derived cells, light grey), pharyngeal endoderm, dorsal pericardial wall and the outflow tract of wild-type (A), Tbx1−/− (C) and compound mutant embryos (D, E). (B) Schematic summary of FGF–BMP signaling axis regulation by Tbx1 and by the redundant action of Tbx2/Tbx3 during pharyngeal and arterial pole morphogenesis. Red arrow in (C), reduced expression of Tbx2 and Tbx3; green arrow in (D), elevated expression of Tbx1. See text for details.

Alterations in FGF and BMP signaling pathways in Tbx2−/−;Tbx3+/− and Tbx2+/−;Tbx3−/− embryos indicate that more than one functional allele of either Tbx2 or Tbx3 is required to correctly regulate these signaling pathway components. The elevated Fgf8 expression in pharyngeal mesoderm of Tbx1/Tbx2/Tbx3 compound mutants potentially results from disrupted BMP signaling and decreased antagonism between these pathways (Fig. 6). BMP signaling is likely to be tightly regulated during normal OFT development, because expanded BMP signaling in Nkx2.5 mutant embryos also leads to failure of heart tube extension (38).

A small percentage of Tbx3−/− embryos display a severe phenotype on a mixed Bl6/CD1 genetic background (Table 1) (23), affecting endodermal Hh-signaling and the expression of Bmp4 and Fgf8 in the SHF and distal OFT, similar to the expression changes observed in Tbx2−/−;Tbx3−/−, Tbx2+/−;Tbx3−/− and Tbx2−/−;Tbx3+/− embryos on a FVB/N background. Tbx1/Tbx2/Tbx3 is thus likely to be part of a larger network comprising other genetic factors that differ between different genetic backgrounds. Furthermore, downregulation of the BMP target genes Msx1 and Msx2 is observed in the pharyngeal region of severely affected Tbx3 mutant embryos, supporting a role for this gene in the regulation of BMP signaling during pharyngeal development (Supplementary Material, Fig. S6F and H).

TBX2 and TBX3 are candidate modifier genes of the cardiopharyngeal phenotypes in TBX1-haploinsufficient 22q11.2DS patients

Tbx1 regulates proliferation and differentiation of cardiac progenitor cells in the SHF, and our data demonstrate that Tbx2/Tbx3 function redundantly to assist in coordinating these crucial developmental processes. While the detailed mechanisms linking Tbx1/Tbx2/Tbx3 function to the regulation of this signaling axis remain to be dissected, our study has shown that in the absence of two components, the Tbx1/Tbx2/Tbx3 regulatory network collapses, severely compromising crucial intercellular Hh, BMP and FGF signaling events during arterial pole morphogenesis (Fig. 6). Interestingly, recent work has shown that DNA variations in TBX1 are unable to fully explain the variable cardiovascular phenotypes in 22q11.2DS patients, highlighting the importance of genetic modifiers of the 22q11.2DS phenotype (44). Using mouse models, genetic interactions have already been identified between Tbx1 and the genes Crkl, Fgf8, Pitx2, Gbx2, Chd7 and Six1/Eya1 (29,45–48). Here, we show that Tbx2 and Tbx3 can be added to this list. Our findings provide new insights into the mechanisms by which polygenic mutations compromise the robustness of cardiac morphogenesis and lead to CVMs. In conclusion, this work highlights the central roles of Tbx1/Tbx2/Tbx3 in conotruncal morphogenesis and identifies TBX2 and TBX3 as potential modifier genes of the cardiopharyngeal phenotypes in TBX1-haploinsufficient 22q11.2DS patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transgenic mice

Tbx1tm1Pa [synonym: Tbx1−; (11)], Tbx1tm1Bld [synonyms: Tbx1LacZ, Tbx1− (12)], Tbx2Δ2 [synonym: Tbx2− (49)], Tbx3tm1Pa [synonym: Tbx3− (50)] and Tbx3tm1.1(cre)Vmc [synonyms: Tbx3Cre, Tbx3− (51)] mice have been described previously. Homozygosity for the abovementioned alleles is also indicated as −/−. All strains were maintained on mixed or outbred (Bl6/CD1 or FVB/N) backgrounds. Embryos were staged considering noon of the day of the copulation plug as embryonic day (E) 0.5. Embryos were isolated in ice-cold 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 1–4 h, examined and processed for ISH or IHC. Genomic DNA obtained from yolk sac or tail biopsies was used for genotyping by polymerase chain reaction, using primers described in the above references.

Immunohistochemistry

Embryos were collected and whole embryos or trunk regions were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated and embedded in paraffin prior to sectioning at 7–12 μm for IHC, ISH and hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining. IHC was performed on hydrated sections treated for 15 min with antigen unmasking solution (Vector) or pressure-cooked for 4 min in antigen unmasking solution (H-3300, Vector Laboratories). The sections were processed according to the TSA tetramethylrhodamine system protocol (NEL702001KT, Perkin Elmer LAS). Primary antibodies were incubated overnight. Primary antibody concentrations were: Tbx1 (1/100, Zymed), Tbx3 (1/200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Islet-1 (1/100, clone 40.2D6, DSHB), AP-2α (1/50, clone 3B5 DSHB), phospho-ERK (1/100, phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Thr202/Tyr204) (20G11) Cell Signaling), phospho-SMAD (1/100, Phospho-Smad1 (Ser463/465)/Smad5 (Ser463/465)/Smad8 (Ser426/428), 9511, Cell Signaling). Secondary antibody concentrations were: anti-species Alexa 488 (1/500, Jackson), Alexa 680 (1/250, Molecular Probes), Alexa 647 (1/250, Molecular Probes), Alexa 568 (1/250, Molecular Probes) and Cy3 (1/500, Jackson). Sections were counterstained with Hoechst, Sytox Green nucleic acid stain (1/30 000; Molecular Probes) or Dapi (1/40 000; Molecular Probes) and observed using an ApoTome microscope (Zeiss).

In situ hybridization

Non-radioactive ISH on sections was performed as described (52) using mRNA probes for the detection of Tbx2, Tbx5 (53), lacZ, Tbx3, Tbx1, Fgf8, Bmp4, Isl1, Mlc2a and Shh (23). Sections were counterstained with Nuclear Fast Red. For whole-mount ISH, embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and processed as described (27).

Ink injection

Visualization of PAA formation at E10.5 by ink injection into the embryonic ventricle was carried out as described (54).

Three-dimensional reconstruction of gene-expression patterns and morphology

Image acquisition of serial sections stained by ISH or IHC and processing for subsequent three-dimensional reconstructions was performed using a previously described method using Amira 5.2 software (55). The mRNA-expression patterns were independently confirmed in at least two additional embryos.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

FUNDING

This work was supported by the European Commission under the FP7 Integrated Project CardioGeNet (HEALTH-2007-B-223463), the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (Vidi grant 864.05.006 to V.M.C. and Mosaic grant 017.004.040 to M.S.R.) and the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale and Agence National pour la Recherche (to R.G.K.).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Jaco Hagoort for his help in preparing the interactive three-dimensional image and Edouard Saint-Michel and Laure Lo-Ré for technical assistance.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wilson D.I., Burn J., Scambler P., Goodship J. DiGeorge syndrome: part of CATCH 22. JMG. 1993;30:852–856. doi: 10.1136/jmg.30.10.852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffman J.I., Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002;39:1890–1900. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pierpont M.E., Basson C.T., Benson D.W., Jr., Gelb B.D., Giglia T.M., Goldmuntz E., McGee G., Sable C.A., Srivastava D., Webb C.L. Genetic basis for congenital heart defects: current knowledge. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Congenital Cardiac Defects Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation. 2007;115:3015–3038. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.183056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buckingham M., Meilhac S., Zaffran S. Building the mammalian heart from two sources of myocardial cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005;6:826–837. doi: 10.1038/nrg1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dyer L.A., Kirby M.L. Sonic hedgehog maintains proliferation in secondary heart field progenitors and is required for normal arterial pole formation. Dev. Biol. 2009;330:305–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rochais F., Mesbah K., Kelly R.G. Signaling pathways controlling second heart field development. Circ. Res. 2009;104:933–942. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.194464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tirosh-Finkel L., Zeisel A., Brodt-Ivenshitz M., Shamai A., Yao Z., Seger R., Domany E., Tzahor E. BMP-mediated inhibition of FGF signaling promotes cardiomyocyte differentiation of anterior heart field progenitors. Development. 2010;137:2989–3000. doi: 10.1242/dev.051649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stankunas K., Shang C., Twu K.Y., Kao S.C., Jenkins N.A., Copeland N.G., Sanyal M., Selleri L., Cleary M.L., Chang C.P. Pbx/Meis deficiencies demonstrate multigenetic origins of congenital heart disease. Circ. Res. 2008;103:702–709. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.175489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoogaars W.M.H., Barnett P., Moorman A.F.M., Christoffels V.M. T-box factors determine cardiac design. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007;64:646–660. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6518-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scambler P.J. The 22q11 deletion syndromes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:2421–2426. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.16.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jerome L.A., Papaioannou V.E. DiGeorge syndrome phenotype in mice mutant for the T-box gene, Tbx1. Nat. Genet. 2001;27:286–291. doi: 10.1038/85845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindsay E.A., Vitelli F., Su H., Morishima M., Huynh T., Pramparo T., Jurecic V., Ogunrinu G., Sutherland H.F., Scambler P.J., et al. Tbx1 haploinsufficieny in the DiGeorge syndrome region causes aortic arch defects in mice. Nature. 2001;410:97–101. doi: 10.1038/35065105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merscher S., Funke B., Epstein J.A., Heyer J., Puech A., Lu M.M., Xavier R.J., Demay M.B., Russell R.G., Factor S., et al. TBX1 is responsible for cardiovascular defects in velo-cardio-facial/DiGeorge syndrome. Cell. 2001;104:619–629. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00247-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu H., Morishima M., Wylie J.N., Schwartz R.J., Bruneau B.G., Lindsay E.A., Baldini A. Tbx1 has a dual role in the morphogenesis of the cardiac outflow tract. Development. 2004;131:3217–3227. doi: 10.1242/dev.01174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelly R.G., Brown N.A., Buckingham M.E. The arterial pole of the mouse heart forms from Fgf10-expressing cells in pharyngeal mesoderm. Dev. Cell. 2001;1:435–440. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liao J., Aggarwal V.S., Nowotschin S., Bondarev A., Lipner S., Morrow B.E. Identification of downstream genetic pathways of Tbx1 in the second heart field. Dev. Biol. 2008;316:524–537. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen L., Fulcoli F.G., Tang S., Baldini A. Tbx1 regulates proliferation and differentiation of multipotent heart progenitors. Circ. Res. 2009;105:842–851. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.200295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vitelli F., Taddei I., Morishima M., Meyers E.N., Lindsay E.A., Baldini A. A genetic link between Tbx1 and fibroblast growth factor signaling. Development. 2002;129:4605–4611. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.19.4605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vitelli F., Lania G., Huynh T., Baldini A. Partial rescue of the Tbx1 mutant heart phenotype by Fgf8: genetic evidence of impaired tissue response to Fgf8. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2010;49:836–840. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bamshad M., Lin R.C., Law D.J., Watkins W.S., Krakowiak P.A., Moore M.E., Franceschini P., Lala R., Holmes L.B., Gebuhr T.C., et al. Mutations in human TBX3 alter limb, apocrine and genital development in Ulnar-mammary syndrome. Nat. Genet. 1997;16:311–315. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christoffels V.M., Smits G.J., Kispert A., Moorman A.F. Development of the pacemaker tissues of the heart. Circ. Res. 2010;106:240–254. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.205419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bakker M.L., Boukens B.J., Mommersteeg M.T.M., Brons J.F., Wakker V., Moorman A.F.M., Christoffels V.M. Transcription factor Tbx3 is required for the specification of the atrioventricular conduction system. Circ. Res. 2008;102:1340–1349. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.169565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mesbah K., Harrelson Z., Theveniau-Ruissy M., Papaioannou V.E., Kelly R.G. Tbx3 is required for outflow tract development. Circ. Res. 2008;103:743–750. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.172858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harrelson Z., Kelly R.G., Goldin S.N., Gibson-Brown J.J., Bollag R.J., Silver L.M., Papaioannou V.E. Tbx2 is essential for patterning the atrioventricular canal and for morphogenesis of the outflow tract during heart development. Development. 2004;131:5041–5052. doi: 10.1242/dev.01378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aanhaanen W.T., Brons J.F., Dominguez J.N., Rana M.S., Norden J., Airik R., Wakker V., de Gier-de Vries C., Brown N.A., Kispert A., et al. The Tbx2+ primary myocardium of the atrioventricular canal forms the atrioventricular node and the base of the left ventricle. Circ. Res. 2009;104:1267–1274. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.192450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Theveniau-Ruissy M., Dandonneau M., Mesbah K., Ghez O., Mattei M.G., Miquerol L., Kelly R.G. The del22q11.2 candidate gene Tbx1 controls regional outflow tract identity and coronary artery patterning. Circ. Res. 2008;103:142–148. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.172189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelly R.G., Jerome-Majewska L.A., Papaioannou V.E. The del22q11.2 candidate gene Tbx1 regulates branchiomeric myogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004;13:2829–2840. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vitelli F., Morishima M., Taddei I., Lindsay E.A., Baldini A. Tbx1 mutation causes multiple cardiovascular defects and disrupts neural crest and cranial nerve migratory pathways. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:915–922. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.8.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calmont A., Ivins S., Van Bueren K.L., Papangeli I., Kyriakopoulou V., Andrews W.D., Martin J.F., Moon A.M., Illingworth E.A., Basson M.A., et al. Tbx1 controls cardiac neural crest cell migration during arch artery development by regulating Gbx2 expression in the pharyngeal ectoderm. Development. 2009;136:3173–3183. doi: 10.1242/dev.028902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zirzow S., Ludtke T.H., Brons J.F., Petry M., Christoffels V.M., Kispert A. Expression and requirement of T-box transcription factors Tbx2 and Tbx3 during secondary palate development in the mouse. Dev. Biol. 2009;336:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goddeeris M.M., Schwartz R., Klingensmith J., Meyers E.N. Independent requirements for Hedgehog signaling by both the anterior heart field and neural crest cells for outflow tract development. Development. 2007;134:1593–1604. doi: 10.1242/dev.02824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garg V., Yamagishi C., Hu T., Kathiriya I.S., Yamagishi H., Srivastava D. Tbx1, a DiGeorge syndrome candidate gene, is regulated by sonic hedgehog during pharyngeal arch development. Dev. Biol. 2001;235:62–73. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamagishi H., Maeda J., Hu T., McAnally J., Conway S.J., Kume T., Meyers E.N., Yamagishi C., Srivastava D. Tbx1 is regulated by tissue-specific forkhead proteins through a common Sonic hedgehog-responsive enhancer. Genes Dev. 2003;17:269–281. doi: 10.1101/gad.1048903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vitelli F., Zhang Z., Huynh T., Sobotka A., Mupo A., Baldini A. Fgf8 expression in the Tbx1 domain causes skeletal abnormalities and modifies the aortic arch but not the outflow tract phenotype of Tbx1 mutants. Dev. Biol. 2006;295:559–570. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aggarwal V.S., Morrow B.E. Genetic modifiers of the physical malformations in velo-cardio-facial syndrome/DiGeorge syndrome. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2008;14:19–25. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crossley P.H., Martin G.R. The mouse Fgf8 gene encodes a family of polypeptides and is expressed in regions that direct outgrowth and patterning in the developing embryo. Development. 1995;121:439–451. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ilagan R., bu-Issa R., Brown D., Yang Y.P., Jiao K., Schwartz R.J., Klingensmith J., Meyers E.N. Fgf8 is required for anterior heart field development. Development. 2006;133:2435–2445. doi: 10.1242/dev.02408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prall O.W.J., Menon M.K., Solloway M.J., Watanabe Y., Zaffran S., Bajolle F., Biben C., McBride J.J., Robertson B.R., Chaulet H., et al. An Nkx2–5/Bmp2/Smad1 negative feedback loop controls heart progenitor specification and proliferation. Cell. 2007;128:947–959. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peterkin T., Gibson A., Patient R. GATA-6 maintains BMP-4 and Nkx2 expression during cardiomyocyte precursor maturation. EMBO J. 2003;22:4260–4273. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naiche L.A., Harrelson Z., Kelly R.G., Papaioannou V.E. T-box genes in vertebrate development. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2005;39:219–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.105925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dupays L., Kotecha S., Mohun T.J. Tbx2 misexpression impairs deployment of second heart field derived progenitor cells to the arterial pole of the embryonic heart. Dev. Biol. 2009;333:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kirby M.L., Hutson M.R. Factors controlling cardiac neural crest cell migration. Cell Adhes. Migr. 2010;4:609–621. doi: 10.4161/cam.4.4.13489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J., Greene S.B., Bonilla-Claudio M., Tao Y., Zhang J., Bai Y., Huang Z., Black B.L., Wang F., Martin J.F. Bmp signaling regulates myocardial differentiation from cardiac progenitors through a microRNA-mediated mechanism. Dev. Cell. 2010;19:903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guo T., McGinn D.M., Blonska A., Shanske A., Bassett A., Chow E., Bowser M., Sheridan M., Beemer F., Devriendt K., et al. Genotype and cardiovascular phenotype correlations with TBX1 in 1,022 velo-cardio-facial/DiGeorge/22q11.2 deletion syndrome patients. Hum. Mutat. 2011;32:1278–1289. doi: 10.1002/humu.21568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nowotschin S., Liao J., Gage P.J., Epstein J.A., Campione M., Morrow B.E. Tbx1 affects asymmetric cardiac morphogenesis by regulating Pitx2 in the secondary heart field. Development. 2006;133:1565–1573. doi: 10.1242/dev.02309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guris D.L., Duester G., Papaioannou V.E., Imamoto A. Dose-dependent interaction of Tbx1 and Crkl and locally aberrant RA signaling in a model of del22q11 syndrome. Dev. Cell. 2006;10:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Randall V., McCue K., Roberts C., Kyriakopoulou V., Beddow S., Barrett A.N., Vitelli F., Prescott K., Shaw-Smith C., Devriendt K., et al. Great vessel development requires biallelic expression of Chd7 and Tbx1 in pharyngeal ectoderm in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:3301–3310. doi: 10.1172/JCI37561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo C., Sun Y., Zhou B., Adam R.M., Li X., Pu W.T., Morrow B.E., Moon A., Li X. A Tbx1-Six1/Eya1-Fgf8 genetic pathway controls mammalian cardiovascular and craniofacial morphogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:1585–1595. doi: 10.1172/JCI44630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wakker V., Brons J.F., Aanhaanen W.T., van Roon M.A., Moorman A.F., Christoffels V.M. Generation of mice with a conditional null allele for Tbx2. Genesis. 2010;48:195–199. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davenport T.G., Jerome-Majewska L.A., Papaioannou V.E. Mammary gland, limb and yolk sac defects in mice lacking Tbx3, the gene mutated in human Ulnar–mammary syndrome. Development. 2003;130:2263–2273. doi: 10.1242/dev.00431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hoogaars W.M.H., Tessari A., Moorman A.F.M., de Boer P.A.J., Hagoort J., Soufan A.T., Campione M., Christoffels V.M. The transcriptional repressor Tbx3 delineates the developing central conduction system of the heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004;62:489–499. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moorman A.F.M., Houweling A.C., de Boer P.A.J., Christoffels V.M. Sensitive nonradioactive detection of mRNA in tissue sections: novel application of the whole-mount in situ hybridization protocol. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2001;49:1–8. doi: 10.1177/002215540104900101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chapman D.L., Garvey N., Hancock S., Alexiou M., Agulnik S.I., Gibson-Brown J.J., Cebra-Thomas J., Bollag R.J., Silver L.M., Papaioannou V.E. Expression of the T-box family genes, Tbx1–Tbx5, during early mouse development. Dev. Dyn. 1996;206:379–390. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199608)206:4<379::AID-AJA4>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kelly R.G., Papaioannou V.E. Visualization of outflow tract development in the absence of Tbx1 using an FgF10 enhancer trap transgene. Dev. Dyn. 2007;236:821–828. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Soufan A.T., van den Berg G., Moerland P.D., Massink M.M.G., van den Hoff M.J.B., Moorman A.F.M., Ruijter J.M. Three-dimensional measurement and visualization of morphogenesis applied to cardiac embryology. J. Microsc. 2007;225:269–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2007.01742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.