Abstract

The National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program provides a rich source of data stratified according to tumor biomarkers that play an important role in cancer surveillance research. These data are useful for analyzing trends in cancer incidence and survival. These tumor markers, however, are often prone to missing observations. To address the problem of missing data, the authors employed sequential regression multivariate imputation for breast cancer variables, with a particular focus on estrogen receptor status, using data from 13 SEER registries covering the period 1992–2007. In this paper, they present an approach to accounting for missing information through the creation of imputed data sets that can be analyzed using existing software (e.g., SEER*Stat) developed for analyzing cancer registry data. Bias in age-adjusted trends in female breast cancer incidence is shown graphically before and after imputation of estrogen receptor status, stratified by age and race. The imputed data set will be made available in SEER*Stat (http://seer.cancer.gov/analysis/index.html) to facilitate accurate estimation of breast cancer incidence trends. To ensure that the imputed data set is used correctly, the authors provide detailed, step-by-step instructions for conducting analyses. This is the first time that a nationally representative, population-based cancer registry data set has been imputed and made available to researchers for conducting a variety of analyses of breast cancer incidence trends.

Keywords: breast neoplasms; imputation; incidence; missing data; receptors, estrogen

Cancer surveillance data provide a window into cancer incidence and survival trends at the population level. As our knowledge of cancer increases, it is clear that, in addition to primary tumor site, factors such as stage at diagnosis, histologic type, and molecular subtype play an important role in understanding cancer risk, prognosis, and disparities within the population. Therefore, analyzing cancer trends according to these characteristics plays an important role in cancer surveillance. Often, individual cases captured in registry data are missing information on these important variables. The amount of missing information may vary between subgroups and can change over time. In recent work, Anderson et al. (1) highlighted the importance of accounting for missing data when assessing trends and showed that ignoring missing information can lead to biased results. In this paper, we describe an approach to accounting for missing information through creation of an imputed data set that can be analyzed using existing software (e.g., SEER*Stat) developed for analyzing cancer registry data in conjunction with standard statistical packages such as SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

To show how to create imputed data sets and make them available to researchers for a variety of analyses, we focus here on breast cancer and examine trends by estrogen receptor (ER) status using data from the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Recent trends for ER-positive (ER+) and ER-negative (ER−) cancers have differed, partially because of the relation between ER+ breast cancer and the use of hormone replacement therapy. As use of hormone replacement therapy has declined in the population, so have the rates of ER+ breast cancer (2). Treatment and prognosis also differ by ER status, and rates of ER+ disease vary by race. As a result, cancer rates and trends estimated on the basis of ER status provide a more complete picture of breast cancer in the United States. However, ER status is prone to missing observations, given the nature of the data. Tissue samples for ER testing are sent to an accredited laboratory that follows specific testing guidelines. This creates a time lag in obtaining complete information. Therefore, ER data can easily be missed by tumor registrars who review medical records during the period when laboratory test results are not yet available (3).

With registry data, we are unable to assume that information is missing completely at random. When we say that data are missing completely at random, we mean that the probability that an observation is missing is unrelated to the value of the observation or to the value of any other variables (4, 5). Although some investigators have imputed ER status for specific analyses (1, 2, 6, 7), few studies to date have carefully examined the reasons why biomarker data are missing from the population-based cancer registries. In a few studies, however, researchers have reported that ER data could be missing disproportionately among certain population subgroups (e.g., black women, persons of lower socioeconomic status) (6). Under these circumstances, examination of temporal trends could be severely biased. Because ER is an important tumor biomarker for breast cancer incidence and survival, it is important to understand the extent of the missing data problem and account properly for the missing information to present the most accurate estimate of rates and trends for the tumor biomarker.

Our objectives in this paper are to 1) describe a process for developing and distributing imputed data sets and 2) apply this process to breast cancer incidence data by describing the missing ER status data patterns and imputing missing data on ER status, along with a suite of key clinical and demographic variables deemed important for analyzing breast cancer trends (e.g., tumor size, race, ethnicity). Prior to our work, a few investigators had imputed missing information on ER status; however, most of these studies employed imputation techniques to address a particular analysis. This paper focuses on a unique situation where missing data in a nationally representative, publicly available data set are imputed and can be used by researchers for a variety of analyses (e.g., to describe breast cancer incidence trends by molecular subtype, such as combinations of ER-plus-progesterone receptor (PR) status stratified by tumor size, and to assess ER− (more aggressive) breast cancer incidence trends across racial groups stratified by ecologic measures of county-level poverty and other variables). The utility of the imputed data set is that it allows investigators to analyze trends by combining variables in any preferred way (e.g., over different time periods, by any age group or race/ethnicity, or by tumor attributes). The imputed data set will be made available in SEER*Stat, software that is used to analyze SEER data (http://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/). To ensure that the imputed data set is used correctly by analysts/researchers, this paper provides detailed, step-by-step instructions for conducting analyses (see Web Appendix 1, which appears on the Journal's website (http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/)).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

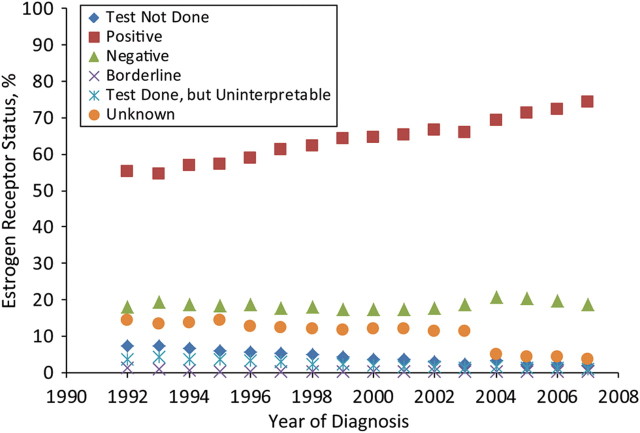

We used population-based data from 13 SEER registries, which represent approximately 14% of the total US population (8). Females with malignant breast cancer diagnosed from 1992 to 2007 were included in the analysis. This yielded a total of 401,741 female patients with malignant breast cancer. SEER collects information on ER status in 6 categories: 1) test not done, 2) positive (+), 3) negative (−), 4) borderline, 5) test done but results missing, and 6) unknown. Figure 1 shows the distribution of ER status over time from 1992 to 2007. The majority of the patients were diagnosed with ER+ tumors, and the distribution of these tumors seemed to be increasing (from 55% in 1992 to 74% in 2007). The incidence of ER− tumors remained fairly flat during this time period, at less than 20% of the overall distribution. Few patients were diagnosed as having an ER status in other categories such as category 1, 4, or 5, and the distributions of these tumor categories were fairly small, at 4%, 2%, and <1%, respectively, with little change over time.

Figure 1.

Distribution of estrogen receptor status over time for female patients with malignant breast cancer in 13 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registries, 1992–2007.

However, we noticed that the distribution of unknown ER status (the orange dots in Figure 1) varied drastically over time. For example, unknown ER status constituted 25% of overall ER status data in 1992; by 2004, unknown ER status represented only 10% of the distribution. This gradual decrease in the amount of ER status data reported missing by the registries did not occur by coincidence. During this time period, the staging classification system used by the cancer registry community changed significantly, and a new staging classification, known as the Collaborative Staging System (9), was proposed in 2004. The new staging system was designed to include more biologic and clinical information regarding the extent of disease. In response to the new system, ER status and many other breast cancer variables became required data items, to be collected by all SEER registries. For simplicity of analysis, we combined the original 6 categories into a 3-level ER status variable for further analysis: 1) ER+ (categories 2 and 4 above), 2) ER− (category 3 above), and 3) missing ER status (categories 1, 5, and 6 above). Distributions of these new ER status categories during 1992–2007 were: ER + , 56%–74%; ER − , 18%–19%; and missing ER status, 7%–25%.

Demographic variables considered important for assessing their relation with ER status included age at diagnosis (in 5-year age groups), SEER registry (San Francisco, California; Connecticut; Detroit, Michigan; Hawaii; Iowa; New Mexico; Seattle, Washington; Utah; Atlanta, Georgia; San Jose-Monterey, California; Los Angeles, California; Alaska; or rural Georgia), year of diagnosis (one of the 16 years 1992–2007), race (white, black, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian/Pacific Islander, or other), and ethnicity (Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic). Important clinical variables included PR status (positive, negative, or unknown), tumor size (≤1, 1.1–2.0, 2.1–3.0, 3.1–4.0, 4.1–5.0, or >5.0 cm), tumor histologic type (ductal, lobular, mixed, or other), lymph node status (positive vs. negative), tumor grade (I, II, III, or IV), and metastasis at diagnosis (yes vs. no). Poverty data (obtained from 2000 US Census data) collected at the county level were used as a surrogate for socioeconomic status. Cutpoints based on empirical research and policy relevance (10, 11) were used to create a 2-level poverty variable (i.e., <10.0% for high socioeconomic status, 10%–100.0% for low socioeconomic status). Web Table 1, which appears on the Journal's website (http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/), presents descriptive statistics for the study population by ER status.

Table 1.

Breast Cancer Incidence Trends for US White Women, by Age and Estrogen Receptor Status, 1992–2007

| Age Group (Years) and ER Status | Joinpoint Trend 1 |

Joinpoint Trend 2 |

Joinpoint Trend 3 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year Range | APC | Year Range | APC | Year Range | APC | |

| All ages | ||||||

| ER+ a, observed | 1992–1999 | 3.3* | 1999–2007 | −0.3 | ||

| ER+ , imputed | 1992–2001 | 1.6* | 2001–2004 | −5.3 | 2004–2007 | 1.3 |

| ER− , observed | 1992–2007 | −0.6* | ||||

| ER− , imputed | 1992–2007 | −2.1* | ||||

| 40–49 | ||||||

| ER+ , observed | 1992–2007 | 2.1* | ||||

| ER+ , imputed | 1992–2000 | 1.6* | 2000–2003 | −2.0 | 2003–2007 | 2.3* |

| ER− , observed | 1992–2007 | −2.0* | ||||

| ER− , imputed | 1992–2007 | −3.1* | ||||

| 50–59 | ||||||

| ER+ , observed | 1992–1999 | 4.8* | 1999–2007 | −1.8* | ||

| ER+ , imputed | 1992–2000 | 3.1* | 2000–2004 | −5.5* | 2004–2007 | −0.04 |

| ER− , observed | 1992–2007 | −1.0* | ||||

| ER− , imputed | 1992–2007 | −2.4* | ||||

| 60–69 | ||||||

| ER+ , observed | 1992–2001 | 3.4* | 2001–2004 | −4.9 | 2004–2007 | 3.6 |

| ER+ , imputed | 1992–2001 | 2.3* | 2001–2004 | −6.7 | 2004–2007 | 2.3 |

| ER− , observed | 1992–2007 | 0.3 | ||||

| ER− , imputed | 1992–2007 | −1.3* | ||||

| ≥70 | ||||||

| ER+ , observed | 1992–1998 | 3.1* | 1998–2007 | −0.4 | ||

| ER+ , imputed | 1992–1999 | 1.4* | 1999–2007 | −2.4* | ||

| ER− , observed | 1992–2007 | 0.4 | ||||

| ER− , imputed | 1992–2007 | −1.7* | ||||

Abbreviations: APC, annual percent change; ER, estrogen receptor.

* P < 0.05.

a ER + , estrogen receptor-positive; ER − , estrogen receptor-negative.

Multiple imputation

Multiple imputation has emerged as an appropriate and flexible way to address the issue of missing data (12). We have employed a method known as sequential regression multivariate imputation (13), which includes a module for imputing categorical variables (5, 13) such as ER status and other breast cancer variables in the data set. A key assumption when using this imputation method is the missing-at-random assumption, which states that the probability of missingness depends only on the associated observed variables (4). Inspection of the missing data patterns (Web Figure 1) suggests that the missing-at-random assumption has been met because the varying degrees of missingness seem to be explained by the different covariates. (Detailed descriptions of the missing data patterns are provided in the Results section.) However, these are theoretical concepts that cannot be tested empirically (5).

The sequential regression multivariate imputation method uses all available observations and variables specified a priori to perform imputation. The idea behind this method is fairly simple: Model each variable with missing observations conditional on the remaining variables in the data set until no variable remains with missing observations. Thus, the final imputed data set would contain not only imputed ER status but also other imputed breast cancer variables with missing observations (e.g., tumor size, node). The imputations themselves are values predicted from regression models, with the appropriate random error included (13).

The procedure we followed to impute values for SEER breast cancer data is as follows: The variable with the least missingness (variable 1) was imputed conditional on all variables with no missingness. We first imputed age at diagnosis (0.01% missing), conditional on SEER registry, year of diagnosis, and ethnicity (variables with no missing values). The variable with the second-least missingness (county poverty, 0.02% missing) was then imputed conditional on the variables with no missing values and variable 1, and so on (i.e., until all of the variables with missing information had been cycled through in this way and there were no longer any missing values in the data set). Each variable was imputed by using a model tailored to its distribution (14). For example, logistic regression was used to impute binary variables, and polynomial regression was used for variables with more than 2 categories (e.g., tumor size). Studies have shown this imputation procedure to be fairly efficient when more than 5–10 imputations yield little added benefit (12). The data set we produced contains 5 possible values for the missing data, based on our having run the imputation 5 times using the IVEware macro, version 0.2 (15), in SAS, version 9.1.

To provide evidence of the reliability of the imputation model, we conducted a simulation study that compared the predicted ER status with the true ER status. Details of this simulation study are presented in the Results section.

Statistical analysis of breast cancer incidence trends

Each imputed data set was used to obtain age-adjusted rates calculated per 100,000 persons, based on the 2000 US standard population, using SEER*Stat software (16). A final age-adjusted rate and standard error were obtained by combining the age-adjusted rate and standard error obtained from each multiply imputed data set using Rubin's rule (4). Trends in observed and imputed age-adjusted cancer incidence rates were analyzed using the Joinpoint Regression Program (version 3.5) (17), which involves fitting a series of joined straight lines on a logarithmic scale to the trends in the annual age-adjusted rates. We allowed a maximum of 2 joinpoints in models for the period 1992–2007. We present trends in incidence using annual percent changes, that is, the slope of the line segment based on observed data. Kim et al. (18) provide more details about the joinpoint model used. The imputed data sets were implemented in SEER*Stat software and can be made available to interested researchers. The data sets are available via different SEER*Stat software sessions, including the frequency and rate sessions. This will enable users to conduct different types of analyses, depending on the research question.

RESULTS

Assessing missing data patterns

Overall, 17% of patients had missing data on ER status (Web Table 1). However, the distribution of missing ER status varied over time (Figure 1). We explored the relation between ER status and important covariates to better understand the extent of the missing data problem. Web Figure 1 shows that the percentage of missing data on ER status was not constant over time for these variables, and the amount of missingness depended on the covariates and levels within each covariate. For example, missing ER status increased with increasing age at diagnosis (e.g., from 24% in 1992 to 6% in 2007 for the age group 50–59 years; from 27% in 1992 to 7% in 2007 for the age group 70–79 years). The distribution of missing ER status data decreased over time for the majority of the registries, with the exception of the New Mexico registry. Blacks had a higher percentage of missing ER status data than whites and Asians/Pacific Islanders (21% for blacks vs. 17% for whites and 15% for Asians/Pacific Islanders). Similarly, Hispanics had a higher percentage of missing ER data than non-Hispanics (33% in 1992 to 10% in 2007 for Hispanics vs. 25% in 1992 to 7% in 2007 for non-Hispanics).

Our data showed a strong correlation between ER status and related tumor characteristics with respect to missingness. For example, if a patient was missing data on ER status, information on other related tumor attributes (PR status, tumor size, node, grade, etc.) for that patient was also likely to be missing. This pattern is evident in Web Figure 1. In addition, patients with larger tumors or higher-grade tumors were slightly more likely to have missing ER status data than patients with smaller tumors or lower-grade tumors (29% in 1992 to 7% in 2007 for ≥5-cm tumors vs. 18% in 1992 to 4% in 2007 for 1- to 2-cm tumors). Similarly, patients diagnosed with more advanced disease were likely to have missing ER status (the distribution of unknown ER status was 30% for patients whose disease was found to have metastasized at diagnosis compared with 15% for those whose disease did not metastasize). The final variable we explored to better understand missing ER status patterns was county-level poverty data. We found a positive association between missing ER status and poorer counties (missing ER status varied from 28% in 1992 to 9% in 2007 for poorer counties vs. 22% in 1992 to 5% in 2007 for less poor counties). The observed missing data patterns revealed that ER status was not missing completely at random. Therefore, analysis of ER data trends according to any selected variables would be biased if the missing observations were simply omitted.

Breast cancer incidence trends before and after imputation

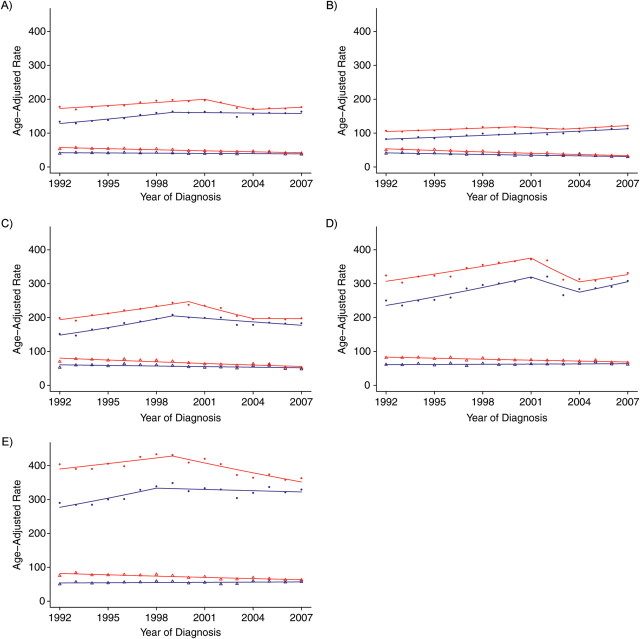

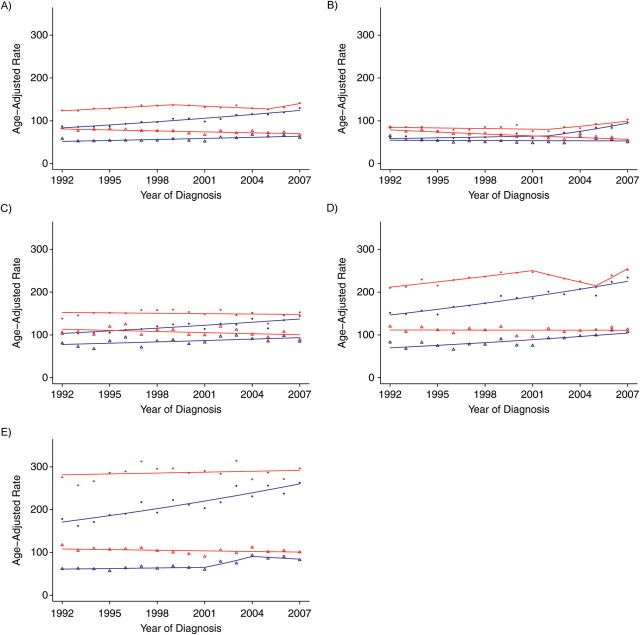

Trend analyses before and after imputation of ER status for white females and black females are presented in Figure 2 and Table 1 (for white females) and Figure 3 and Table 2 (for black females), respectively, for all ages combined and according to 10-year age group for patients over age 40 years. As would be expected, age-adjusted rates based on imputed ER status were higher than those based on observed (i.e., unimputed) ER status because cases with missing ER status were allocated to an ER+ or ER− category after imputation. For example, age-adjusted rates in 1992 for black females with ER+ tumors were 87.5 per 100,000 (standard error (SE), 3.1) for observed ER status versus 124.0 per 100,000 (SE, 4.0) for imputed ER status. Similarly, ER− tumor rates were 58.3 per 100,000 (SE, 2.5) for observed ER status versus 83.3 per 100,000 (SE, 3.4) for imputed ER status. In addition, there were smaller differences between the observed and imputed incidence rates for the younger females as compared with older females (because of fewer missing data in younger age groups). For example, for white females diagnosed in 1992 with ER+ tumors, the relative difference between the observed and imputed rates was 29.6% for the age group 40–49 years as compared with 38.4% for the age group ≥70 years. The relative difference in rates between the younger and older groups persisted in varying magnitudes across race, ER tumor status, and time.

Figure 2.

Breast cancer incidence trends for US white women according to estrogen receptor (ER) status (observed vs. imputed), 1992–2007. A) All age groups; B) ages 40–49 years; C) ages 50–59 years; D) ages 60–69 years; E) ages ≥70 years. Blue dot, ER-positive observed rate; red dot, ER-positive imputed rate; blue triangle, ER-negative observed rate; red triangle, ER-negative imputed rate. The blue line denotes the rate modeled by the Joinpoint Regression Program for the ER observed trend; the red line denotes the Joinpoint-modeled rate for the ER imputed trend.

Figure 3.

Breast cancer incidence trends for US black women according to estrogen receptor (ER) status (observed vs. imputed), 1992–2007. A) All age groups; B) ages 40–49 years; C) ages 50–59 years; D) ages 60–69 years; E) ages ≥70 years. Blue dot, ER-positive observed rate; red dot, ER-positive imputed rate; blue triangle, ER-negative observed rate; red triangle, ER-negative imputed rate. The blue line denotes the rate modeled by the Joinpoint Regression Program for the ER observed trend; the red line denotes the Joinpoint-modeled rate for the ER imputed trend.

Table 2.

Breast Cancer Incidence Trends for US Black Women, by Age and Estrogen Receptor Status, 1992–2007

| Age Group (Years) and ER Status | Joinpoint Trend 1 |

Joinpoint Trend 2 |

Joinpoint Trend 3 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year Range | APC | Year Range | APC | Year Range | APC | |

| All ages | ||||||

| ER+ a, observed | 1992–2007 | 2.7* | ||||

| ER+ , imputed | 1992–1999 | 1.6* | 1999–2005 | −1.2 | 2005–2007 | 4.8 |

| ER− , observed | 1992–2007 | 1.4* | ||||

| ER− , imputed | 1992–2007 | −1.0* | ||||

| 40–49 | ||||||

| ER+ , observed | 1992–2002 | 1.1 | 2002–2007 | 7.8* | ||

| ER+ , imputed | 1992–2002 | −0.6 | 2002–2007 | 4.4* | ||

| ER− , observed | 1992–2007 | −0.2 | ||||

| ER− , imputed | 1992–2007 | −2.2* | ||||

| 50–59 | ||||||

| ER+ , observed | 1992–2007 | 1.9* | ||||

| ER+ , imputed | 1992–2007 | −0.2 | ||||

| ER− , observed | 1992–2007 | 1.3* | ||||

| ER− , imputed | 1992–2007 | −0.8 | ||||

| 60–69 | ||||||

| ER+ , observed | 1992–2007 | 2.9* | ||||

| ER+ , imputed | 1992–2001 | 1.9* | 2001–2005 | −3.7* | 2005–2007 | 8.9* |

| ER− , observed | 1992–2007 | 2.7* | ||||

| ER− , imputed | 1992–2007 | −0.04 | ||||

| ≥70 | ||||||

| ER+ , observed | 1992–2007 | 2.8* | ||||

| ER+ , imputed | 1992–2007 | 0.2 | ||||

| ER− , observed | 1992–2001 | 0.7 | 2001–2004 | 11.7 | 2004–2007 | −2.4 |

| ER− , imputed | 1992–2007 | −0.5 | ||||

Abbreviations: APC, annual percent change; ER, estrogen receptor.

* P < 0.05.

a ER+ , estrogen receptor-positive; ER− , estrogen receptor-negative.

Figure 2 shows results from trend analysis using observed and imputed ER status for white female breast cancer patients, stratified by age at diagnosis. The annual percent change estimate for each trend segment is shown in Table 1. A summary of the results for ER+ trends follows. Observed ER+ tumor incidence rates for all ages combined increased by 3.3% (per year) from 1992 to 1999, followed by a non-statistically significant decrease of 0.3% (per year) from 1999 to 2007. In contrast, imputed ER+ tumor incidence rates showed a different trend during this time period: a 1.6% (per year) increase from 1992 to 2001, followed by a nonsignificant decrease of 5.3% (per year) from 2001 to 2004 and a non-statistically significant increase of 1.3% (per year) during the most recent time period (2005–2007). For the age group 50–59 years, we noticed an increasing observed ER+ trend (4.8% per year) up to 1999, followed by a decreasing trend (−1.8% per year) from 1999 to 2007. The imputed ER+ trend is similar to the observed trend in the first segment (3.1% from 1992 to 2000). However, with imputed ER status, a new joinpoint was detected in 2000. This new joinpoint splits the last segment of 1999–2007 into 2 segments, showing a statistically significant decrease of 5.5% (per year) from 2000 to 2004, followed by a non-statistically significant decrease of 0.04% (per year) from 2004 to 2007. The detection of a new joinpoint in this age group is important because it captures a well documented (2, 19–22) change in breast cancer incidence around 2002, after results from the Women's Health Initiative (23) were published. Without correcting for the changing distribution of missing ER status over time, we would not have been able to detect this important phenomenon for this group of women between the ages of 50 and 69 years. For women aged ≥70 years, the observed ER+ trend for 1998–2007 went from a non-statistically significant decrease of 0.4% (per year) to a rapid statistically significant decrease of 2.4% (per year) with the imputed ER+ trend in the most recent period. We also found modest differences between the imputed ER+ trend and the observed ER+ trend for the age groups 40–49 and 60–69 years.

Comparing the ER− trends in the observed and imputed data for all ages also showed some modest differences (Figure 2). The ER− observed incidence trend decreased slowly, by 0.6% (per year), whereas the imputed trend decreased much faster, by 2.1% (per year) over the entire period (1992–2007; Table 1). A similar pattern between the observed and imputed trends was observed for the age groups 40–49 and 50–59 years. Interesting differences between the observed and imputed ER− trends were noted for the older ages. For example, for women aged ≥70 years, the observed ER− trend increased nonsignificantly by 0.4% (per year), whereas the ER− negative imputed trend decreased rapidly over this period by 1.7% (per year). The decreasing ER− trend for older women would not have been detected without accounting for missing ER status. A similar trend was observed for the ER− trend in the age group 60–69 years. A similar decreasing trend with the redistributed ER− tumors was reported in a recent study (1).

Figure 3 and Table 2 show the trend analysis for black female breast cancer patients. The ER+ observed trend increased during the entire study period, whereas the imputed ER+ trend showed more variability (see Table 2). The observed ER− trend increased by 1.4% (per year), whereas the imputed ER− trend decreased by 1.0% (per year). The decreasing trend for imputed ER− data can partially be explained by the reallocation of the missing ER values. Because there was a much higher percentage of missing ER status data in the earlier period, the reallocation of a certain proportion of missing ER data to ER− inflates the earlier part of the trend, whereas the later part of the trend is little affected, as the quantity of missing data in recent years was smaller.

Simulation study

To provide evidence of reliability for our imputation model, we performed a simulation study using a subset of data for which the ER status was known. We then generated missing-at-random data with the same pattern of missingness as the original data set to preserve the relations between other variables and ER status. To reduce computation time, we randomly sampled 1% of the missing-at-random data set and produced 100 training data sets on which we conducted sequential regression multivariate imputations separately. We then compared the concordance between imputed and true ER status after performing the imputation for each data set using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. The average area under the curve across these 100 data sets was estimated to be 0.92. Because there was good agreement between imputed and true ER status, we feel confident in our model prediction. In addition, our model fit was good (pseudo-R2 = 0.69). We also computed the fraction of missing information (FMI), a positive number between 0 and 1 that is calculated as a ratio of between-imputation variance and total variance (4). The FMI is used to reflect statistical uncertainty due to missing data in results across the imputed data sets. The average FMI based on the imputation model for ER+ tumors was 6%; for ER− tumors, it was 12%. Here, the FMI is specific to the ER status category being estimated. The differing FMI for ER+ and ER− tumors reflects the differing amounts of imputation in these groups. The relatively small value of the average FMI implies that the prediction was stable across the different imputations.

DISCUSSION

Missing values can present a serious problem in the analysis of cancer registry data. Several techniques can be used to address the problem. The appropriateness of the chosen method depends on the nature of the missing data and how well the assumptions can be justified. Modeling missing data with imputation requires making certain assumptions about the missing data mechanism. A second important concern with regard to modeling missing data relates to how well the model is able to predict missing observations. In our analysis, we observed that missing ER status on average was being allocated approximately 75% to ER+ status and approximately 25% to ER− status (data not shown). Age at diagnosis is one of the most important predictors of ER status; increasing age is associated with ER+ tumors, and decreasing age is associated with ER− tumors. In Web Table 1, we show that as age increased, missing data on ER status increased as well. For example, overall missing ER status varied from 15.3% for women aged <50 years to 16.9% for those aged 65–74 years and 22.4% for those aged ≥75 years. We examined groups stratified by age, race, and year of diagnosis and found that expected distributions to ER tumors for the subgroups were similar to the overall model.

Another consideration when developing an imputation model is to ensure the inclusion of all of the important predictors of the outcome (5). Because we were using population-based cancer registry data, we did not have information on several important risk factors for ER status (e.g., duration of hormone therapy, nulliparity, late age at first pregnancy, postmenopausal obesity) (6). Also, as noted by many missing-data experts (12), an imputation method relies on inherently untestable assumptions, and the accuracy of the specified conditional distributions is uncertain. Therefore, some degree of caution should be exercised when using these imputed data sets for making inferences with respect to trends.

No evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for the use of tumor markers in the prevention, screening, treatment, and surveillance of breast cancer were available before 1996 (24). Therefore, it is possible that physicians did not ask all patients with invasive breast cancer to have their tumors tested for estrogen and progesterone receptors prior to that time. This could explain in part the larger amount of missing ER/PR data in the early 1990s. As time progressed and testing for these breast cancer tumor markers became part of standard care, the completeness of ER/PR data improved. Concurrently, new guidelines were developed that established cutoff values for determining ER/PR positivity (25). In our analysis, we were not able to account for changes in ER/PR testing over time.

In summary, we have carefully examined and addressed missing data for several important tumor characteristics that often are used to describe current breast cancer trends in the United States. In reporting cancer trends, a change of as little as 1% per year demonstrates improvement or prompts alert in cancer control efforts. Such changes could easily be obscured without proper adjustment for any missing data. More importantly, because data collection on several clinical and molecular factors such as human epidermal growth factor receptor 2/neu is well under way (26), it will be even more important to be able to develop and distribute these imputed data sets, as the initial years of data collection for these variables will probably include many missing observations. With the aid of these imputed data sets, we can provide researchers with tools to better understand the molecular and genetic alterations in breast cancer incidence and report trends in the most accurate manner.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author affiliation: Data Analysis and Interpretation Branch, Surveillance Research Program, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland (Nadia Howlader, Anne-Michelle Noone, Mandi Yu, Kathleen A. Cronin).

This work was supported by the Surveillance Research Program, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute.

The authors thank Drs. Brenda K. Edwards, Eric J Feuer, and Minjung Lee for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson WF, Katki HA, Rosenberg PS. Incidence of breast cancer in the United States: current and future trends. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(18):1397–1402. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr257. ( doi:10.1093/jnci/djr257) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ravdin PM, Cronin KA, Howlader N, et al. The decrease in breast-cancer incidence in 2003 in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(16):1670–1674. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr070105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fritz A, Ries L. SEER Program Code Manual. 3rd. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 1998. (http://seer.cancer.gov/manuals/codeman.pdf. ). (Accessed February 2, 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis With Missing Data. 2nd. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allison PD. Missing Data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krieger N, Chen JT, Ware JH, et al. Race/ethnicity and breast cancer estrogen receptor status: impact of class, missing data, and modeling assumptions. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19(10):1305–1318. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9202-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfeiffer RM, Mitani A, Matsuno RK, et al. Racial differences in breast cancer trends in the United States (2000–2004) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(10):751–752. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence—SEER 17 Regs Research Data + Hurricane Katrina Impacted Louisiana Cases, Nov 2009 Sub (1973–2007 Varying)—Linked to County Attributes—Total U.S., 1969–2007 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch, Released April 2010, Based on the November 2009 Submission [database] Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2010; (www.seer.cancer.gov. ). (Accessed February 2, 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collaborative Staging Task Force of the American Joint Committee on Cancer. Collaborative Staging Manual and Coding Instructions, Version 01.04.00. 2004. (Incorporates updates through September 8, 2006) Chicago, IL: American Joint Committee on Cancer; and Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute (NIH publication no. 04-5496) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh GK, Miller BA, Hankey BF, et al. Area Socioeconomic Variations in U.S. Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Stage, Treatment, and Survival, 1975–1999. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2003. (NCI Cancer Surveillance Monograph Series, no. 4). (NIH publication no. 03-5417) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, et al. Geocoding and monitoring of US socioeconomic inequalities in mortality and cancer incidence: does the choice of area-based measure and geographic level matter?: the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(5):471–482. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horton NJ, Kleinman KP. Much ado about nothing: a comparison of missing data methods and software to fit incomplete data regression models. Am Stat. 2007;61(1):79–90. doi: 10.1198/000313007X172556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, van Hoewyk J, et al. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Surv Methodol. 2001;27(1):85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allison PD. SUGI 30 Proceedings. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, April 10–13, 2005. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2005. Imputation of categorical variables with PROC MI. (Paper 113-30) (http://www2.sas.com/proceedings/sugi30/113-30.pdf. ). (Accessed February 2, 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Survey Methodology Program, Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. IVEware: Imputation and Variance Estimation Software. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2011. (http://www.isr.umich.edu/src/smp/ive/ ). (Accessed February 2, 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Surveillance Research Program, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute. SEER*Stat Software, Version 7.0.4. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2010. (http://www.seer.cancer.gov/seerstat. ). (Accessed February 2, 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Surveillance Research Program, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute. Joinpoint Regression Program. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2011. (http://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/ ). (Accessed February 2, 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, et al. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19(3):335–351. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::aid-sim336>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeSantis C, Howlader N, Cronin KA, et al. Breast cancer incidence rates in U.S. women are no longer declining. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(5):733–739. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jemal A, Ward E, Thun MJ. Recent trends in breast cancer incidence rates by age and tumor characteristics among U.S. women. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9(3):R28. doi: 10.1186/bcr1672. ( doi:10.1186/bcr1672) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cronin KA, Ravdin PM, Edwards BK. Sustained lower rates of breast cancer in the United States. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;117(1):223–224. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0226-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glass AG, Lacey JV, Jr, Carreon JD, et al. Breast cancer incidence, 1980–2006: combined roles of menopausal hormone therapy, screening mammography, and estrogen receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(15):1152–1161. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris L, Fritsche H, Mennel R, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2007 update of recommendations for the use of tumor markers in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(33):5287–5312. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Dowsett M, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer (unabridged version) Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134(7):e48–e72. doi: 10.5858/134.7.e48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reichman ME, Altekruse S, Li CI, et al. Feasibility study for collection of HER2 data by National Cancer Institute (NCI) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program central cancer registries. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(1):144–147. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]