Abstract

Health risk assessments of particulate matter less than 2.5 μm in diameter (PM2.5) often assume that all constituents of PM2.5 are equally toxic. While investigators in previous epidemiologic studies have evaluated health risks from various PM2.5 constituents, few have conducted the analyses needed to directly inform risk assessments. In this study, the authors performed a literature review and conducted a multisite time-series analysis of hospital admissions and exposure to PM2.5 constituents (elemental carbon, organic carbon matter, sulfate, and nitrate) in a population of 12 million US Medicare enrollees for the period 2000–2008. The literature review illustrated a general lack of multiconstituent models or insight about probabilities of differential impacts per unit of concentration change. Consistent with previous results, the multisite time-series analysis found statistically significant associations between short-term changes in elemental carbon and cardiovascular hospital admissions. Posterior probabilities from multiconstituent models provided evidence that some individual constituents were more toxic than others, and posterior parameter estimates coupled with correlations among these estimates provided necessary information for risk assessment. Ratios of constituent toxicities, commonly used in risk assessment to describe differential toxicity, were extremely uncertain for all comparisons. These analyses emphasize the subtlety of the statistical techniques and epidemiologic studies necessary to inform risk assessments of particle constituents.

Keywords: meta-analysis, nitrates, particulate matter, risk assessment, soot, sulfates

Public policy assessments have demonstrated that the health benefits associated with reducing concentrations of fine particulate matter, defined as particulate matter less than 2.5 μm in diameter (PM2.5), dominate the benefits of air pollution control (1, 2). These health risk assessments of PM2.5 link atmospheric dispersion model outputs with concentration-response functions (CRFs; the percent change in a given health outcome per μg/m3 change in concentration) for PM2.5 as a whole, derived from epidemiologic evidence. However, on the basis of both toxicologic and epidemiologic evidence (3, 4), there has been growing concern that different constituents of PM2.5 may have different levels of toxicity, which would contribute to biases in risk assessments dominated by PM2.5.

With increasing epidemiologic evidence regarding the health effects of PM2.5 constituents, it is timely to consider whether there is sufficient evidence to quantitatively assign different CRFs to different constituents. Advisory committees and recent regulatory analyses (4, 5) have concluded that it is not currently possible to do so. This could be true if there were few relevant studies, an issue that should be resolved over time, but the studies themselves may have fundamental limitations. Exposure data may be insufficient or flawed, or the data may be adequate but the statistical methods applied may not provide the information necessary to draw conclusions about differential toxicity. The different constituents of PM2.5 might affect different health outcomes, and the time scales of toxicity (acute vs. chronic) might vary across constituents and health outcomes. It may also be challenging to combine information across studies, because of underlying geographic variability, differences in statistical methods, and which constituents, health outcomes, and confounders are examined.

To frame the information needs, it is important to consider what risk assessment requires. Risk assessments often evaluate control strategies influencing numerous particle constituents, all of which would require CRFs. Estimates of the public health burden of PM2.5 should be identical regardless of whether they are calculated from total particle mass or by combining the impacts attributed to individual constituents. Relatedly, because the primary risk assessment application of differential toxicity would be in regulatory analyses focused on PM2.5, it is most salient to consider those constituents that could best explain the PM2.5 epidemiology. In addition, risk assessments require reasonable quantification of uncertainty, to convey information to decision-makers and to allow for uncertainty propagation. This would be needed both for individual constituents and in the comparisons between constituents. These comparisons would need to take into account the correlations among the CRFs derived from multiconstituent models. Finally, CRFs should be derived from studies conducted in settings that could be readily generalized to the risk assessment context (i.e., similar ambient concentrations, multipollutant exposures, and population characteristics). There is evidence of geographic variability in CRFs for PM2.5 (6, 7), which may be partly associated with particle composition but also may be related to differences in personal exposure, spatial heterogeneity of constituents, and susceptibility patterns.

In this study, we characterized the differential toxicities of PM2.5 constituents and associated uncertainty by reviewing the literature and conducting a large multisite time-series analysis. We examined the available epidemiologic studies to determine whether they supported any quantitative inferences given the requirements of risk assessments. We then conducted an updated analysis of a national data set for which Peng et al. (8) previously provided CRFs for multiple particle constituents, incorporating additional data, evaluating results by geographic region, and conducting new analyses deemed necessary for risk assessment. Our analysis included estimation of the joint posterior distribution of the short-term effects of individual constituents on cardiovascular and respiratory hospital admissions (CHA and RHA, respectively). Posterior samples from this joint posterior distribution allowed us to calculate relevant values for risk assessment, including posterior probabilities that individual constituents had greater short-term effects on CHA or RHA than other constituents or PM2.5 as a whole.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature review

In October 2010, we searched the Science Citation Index with the keywords “(PM2.5 or fine particulate matter) and health,” a broad search criterion used to ensure that relevant studies were not missed. We reviewed the abstracts of all 1,338 articles found to identify primary epidemiologic studies that evaluated at least one of the following constituents: sulfate, nitrate, elemental carbon, and organic carbon matter. While multiple metals and other constituents could influence health, we focused on constituents that dominate PM2.5 mass and are significantly correlated with PM2.5, since only those constituents could explain the PM2.5 epidemiology. Using these criteria, Peng et al. (8) included the above constituents, as well as silicon, sodium, and ammonium. However, silicon and sodium contributed little mass and were statistically insignificant, and ammonium could not be included in multiconstituent models with sulfate and nitrate, given high correlations.

From the 65 remaining studies, we excluded studies that did not provide adequate information with which to quantify a CRF for at least one constituent, including a lack of information on confidence intervals or concentration units. We also eliminated studies that used factor analysis or other approaches to derive source signatures, because such studies did not provide estimates for individual constituents. We took the remaining 42 studies to comprise the core epidemiologic literature for evaluating differential PM2.5 toxicity.

We gathered the reported relative risks or effect estimates and their associated statistical uncertainty from each study, implicitly assuming linearity of CRFs across the range of concentrations observed in the 42 studies. We also extracted information on health outcomes, statistical methods (including whether the estimate had been derived from a model that included multiple constituents), and other factors relevant to comparing or pooling estimates across studies. For health outcomes and PM2.5 constituents for which a sufficient number of publications existed, we performed inverse-variance weighted meta-analysis, accounting for between-study heterogeneity (9), and compared the resulting CRFs across constituents.

Multisite time-series analysis

We obtained billing claims information for US Medicare enrollees in 119 counties for the years 2000–2008, corresponding to the analysis by Peng et al. (8) but with 2 more years of data. The claims data did not include individually identifiable information, so we did not obtain consent from individual study participants. This study was reviewed and exempted by the institutional review board at the Harvard School of Public Health.

The Medicare billing claims data were classified into disease categories (e.g., cardiovascular disease) according to their International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), codes. While claims information also includes age and gender, data were aggregated across these variables. We considered CHA (ICD-9 codes 390.xx–459.xx) and RHA (ICD-9 codes 464.xx–466.xx and 480.xx–487.xx).

As in the literature review, we considered sulfate, nitrate, elemental carbon, and organic carbon matter. Air pollution data were obtained from the Environmental Protection Agency’s PM2.5 Chemical Speciation Trends Network. Additional data for PM2.5 concentrations were obtained from the agency’s Air Quality System. All data were summarized and processed as described by Peng et al. (8).

Counties were analyzed separately, and county-level results were aggregated across large geographic regions using a Bayesian multivariate normal hierarchical model. Specifically, county-level time-series data were analyzed using log-linear Poisson regression models with overdispersion that used hospital admission counts as outcomes and particle constituents and potential confounders as dependent variables. More specifically, in each county-level model, we included 8 explanatory variable categories: 1) an offset of the log count of the at-risk population; 2) linear terms for sulfate, nitrate, elemental carbon, and organic carbon matter; 3) a smoothing spline for time (t = 1 for January 1, 2000, t = 2 for January 2, 2000, etc.) with 8 degrees of freedom (df) per year; 4) indicator variables for each day of the week; 5) a 6-df spline for temperature; 6) a 6-df spline for 3-day moving average of temperature; 7) a 3-df spline for average daily dew-point temperature; and 8) a 3-df spline for 3-day moving average of dew-point temperature. The splines in categories 5–8 were used to flexibly model the response function of the 4 confounding variables. Results were previously found to be insensitive to the number of degrees of freedom in these splines (8). We only considered lag 0 concentrations, in spite of prior evidence that some constituent-outcome pairs had greater effects at lag 1 or 2 (8), because of concerns about multiple comparisons and statistical challenges in including multiple lag terms given 1-in-6-day sampling and our multiconstituent modeling approach.

Within each county-level analysis, we obtained the point estimates of the short-term effects of the 4 constituents, , and the associated covariance matrix Vc. These results were aggregated across counties using the following Bayesian multivariate hierarchical modeling:

where is the vector of the true county-specific health effects, β = (βA, βB, βC, βD) is the vector of the true overall health effects, and Σ is the covariance matrix of the βc across counties. The hierarchical model defined above was fitted using TLNise 2-level normal independence sampling estimation software (10). We pooled the county-specific results separately for the West and the East (as defined by 100°W longitude) and nationally. TLNise provided 1) samples from the joint posterior distribution of the health effects of the 4 constituents, denoted by p(βA, βB, βC, βD|data), and 2) samples from the posterior distribution of the 4 × 4 covariance matrix, denoted by p(Σ|data). Posterior samples from p(βA, βB, βC, βD|data) allowed us to calculate 1) the posterior probability that βi ≥ βj; 2) posterior correlations between each pair of health effects Cor(βi, βj); and 3) the posterior distribution of toxicity ratios βi|βj. Posterior samples p(Σ|data) allowed us to calculate 1) the posterior distribution of the variance across counties of each parameter () and 2) the posterior distribution of the correlation across counties of each pair of health effects . Separate county-level models were also fitted with a linear term for PM2.5 concentration replacing the terms representing the constituents. The posterior probability that constituent A is more toxic than or equally as toxic as PM2.5 was computed as the fraction of posterior samples from the 2 separate models, where βA ≥ βPM2.5. Statistical analyses were performed using R, version 2.11.1 (R Development Core Team, 2010; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

For the 42 studies identified within the literature review (8, 11–51), there was substantial heterogeneity in health outcomes, constituents included, geographic locations, and statistical methods (see Web Appendix and Web Tables 1–8, which appear on the Journal’s website (http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/)). While the majority of studies addressed elemental carbon or sulfate, fewer than half considered organic carbon matter or nitrate. For those studies evaluating elemental carbon, some used coefficient of haze as the exposure metric, while others used black smoke, black carbon, or elemental carbon, complicating joint interpretation of estimates. Only 8 studies provided quantitative estimates for all 4 constituents, including the previous national-scale Medicare assessment and studies in Atlanta and California (8, 21, 27, 29, 38–41). The reported effect estimates were almost all from single-constituent models (which may have adjusted for gaseous pollutants and other confounders but only included 1 particle constituent at a time). A few investigators did construct multiconstituent models, but quantitative results were generally not reported or were presented for a subset of constituents.

The largest numbers of CRFs were available for all-cause mortality from time-series studies, although only one of these studies reported multiconstituent CRFs. In spite of the limitations of these estimates (including the possibility that some CRFs could be overestimated), we quantitatively pooled the single-constituent model estimates to illustrate some of the challenges in determining differential CRFs from the current literature.

Pooling the 11 all-cause time-series mortality estimates (Web Table 1) yielded an estimated 1.2% increase in mortality per 10-μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 concentrations (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.5, 1.9). Only 4 of these studies provided estimates for elemental carbon with concentration measured in μg/m3 (rather than coefficient of haze units). There were 2 estimates for organic carbon matter, 11 for sulfate, and 4 for nitrate. Pooled analyses for the individual constituents yielded estimates of 0.4% (95% CI: −0.4, 1.2), 1.4% (95% CI: −0.9, 3.7), 2.8% (95% CI: 0.9, 4.6), and 2.7% (95% CI: −0.7, 6.1) per 10-μg/m3 increase in elemental carbon, organic carbon matter, sulfate, and nitrate concentrations, respectively. Based on the central estimates only, these data would seem to imply that organic carbon matter, sulfate, and nitrate are more toxic per unit of concentration than PM2.5 as a whole.

However, focusing solely on the central estimates does not appropriately represent the evidence. Information is not available in the literature for quantifying the probabilities that individual constituents had greater CRFs than other constituents. Even if we restrict the analysis to pairwise comparisons (i.e., looking at the 4 studies with estimates for both elemental carbon and PM2.5 to determine whether the pooled estimates differ), without knowing the correlations among CRFs, we can do little other than examine central estimates. For these pairwise comparisons, elemental carbon, sulfate, and nitrate all have central estimates greater than that for PM2.5, with a slightly lower central estimate for organic carbon matter than for PM2.5. Given that these 4 constituents contribute approximately two-thirds of PM2.5 mass nationally (52), and close to 80% if ammonium is included, it is unlikely that all 4 have comparable or greater toxicity than PM2.5.

The earlier analysis of the Medicare database (8) was the only study to provide any probabilistic insight about differential toxicity, but Peng et al. only reported the posterior probability that elemental carbon had a larger coefficient than the average of the other constituents for CHA. Therefore, the published literature does not provide the necessary information for incorporating differential toxicity into risk assessment, necessitating new analyses.

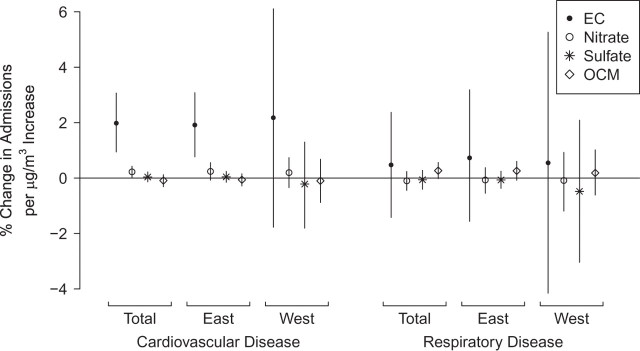

In our multisite time-series analysis, we estimated the percent change in CHA and RHA associated with a 1-μg/m3 increase in each of the 4 constituents, aggregated to national and regional levels (Figure 1). Elemental carbon concentrations are strongly associated with changes in CHA. Elemental carbon also has the largest central estimate per unit change in concentration for RHA, although organic carbon matter has a greater impact per interquartile-range change in concentrations and greater statistical significance.

Figure 1.

Percent change in hospital admissions per μg/m3 increase in concentrations of fine particulate matter constituents, by region of the United States and disease, 2000–2008. Bars, 95% confidence interval. (EC, elemental carbon; OCM, organic carbon matter).

Table 1 shows the pairwise probabilities that each constituent has greater toxicity than another per unit of concentration change. There is a high posterior probability that elemental carbon is more toxic than other constituents (>0.99) for CHA nationally and in the East, with lower probabilities in the West. Comparisons among other constituents are more equivocal. For RHA, the probabilities are closer to 0.5, with the highest probabilities being seen for organic carbon matter in comparison with nitrate and sulfate. Table 1 also provides the posterior probabilities that each constituent is more toxic than PM2.5 as a whole. For example, for CHA nationally, there are high probabilities that elemental carbon and nitrate have greater toxicity than PM2.5 (1 and 0.940, respectively), a low probability (0.094) that organic carbon matter has greater toxicity than PM2.5, and approximately equal probabilities that sulfate has greater or lesser toxicity than PM2.5.

Table 1.

Pairwise Posterior Probability that a Particular Constituent of PM2.5 Had Greater Toxicity than Other Constituents, Expressed as Beta Coefficient per Unit Change in Concentration, United States, 2000–2008a

| Cardiovascular Hospital Admissions | Respiratory Hospital Admissions | |||||||

| Nitrate | Sulfate | Organic Carbon Matter | PM2.5 | Nitrate | Sulfate | Organic Carbon Matter | PM2.5 | |

| All 119 US counties | ||||||||

| Elemental carbon | 0.999 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.710 | 0.719 | 0.576 | 0.669 |

| Nitrate | 0.890 | 0.977 | 0.940 | 0.447 | 0.055 | 0.194 | ||

| Sulfate | 0.802 | 0.427 | 0.125 | 0.253 | ||||

| Organic carbon matter | 0.094 | 0.924 | ||||||

| Eastern counties (n = 98) | ||||||||

| Elemental carbon | 0.996 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.740 | 0.742 | 0.641 | 0.712 |

| Nitrate | 0.827 | 0.924 | 0.870 | 0.496 | 0.124 | 0.280 | ||

| Sulfate | 0.750 | 0.435 | 0.096 | 0.203 | ||||

| Organic carbon matter | 0.131 | 0.869 | ||||||

| Western counties (n = 21) | ||||||||

| Elemental carbon | 0.850 | 0.874 | 0.852 | 0.868 | 0.613 | 0.658 | 0.558 | 0.593 |

| Nitrate | 0.692 | 0.740 | 0.718 | 0.602 | 0.342 | 0.411 | ||

| Sulfate | 0.436 | 0.345 | 0.286 | 0.330 | ||||

| Organic carbon matter | 0.324 | 0.675 | ||||||

Abbreviation: PM2.5, particulate matter less than 2.5 μm in diameter.

Each value represents the probability that the row constituent is more toxic than the column constituent.

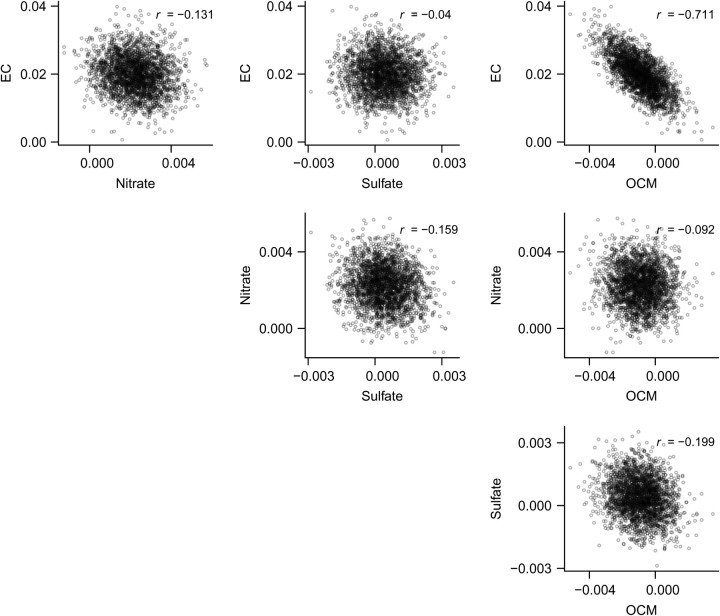

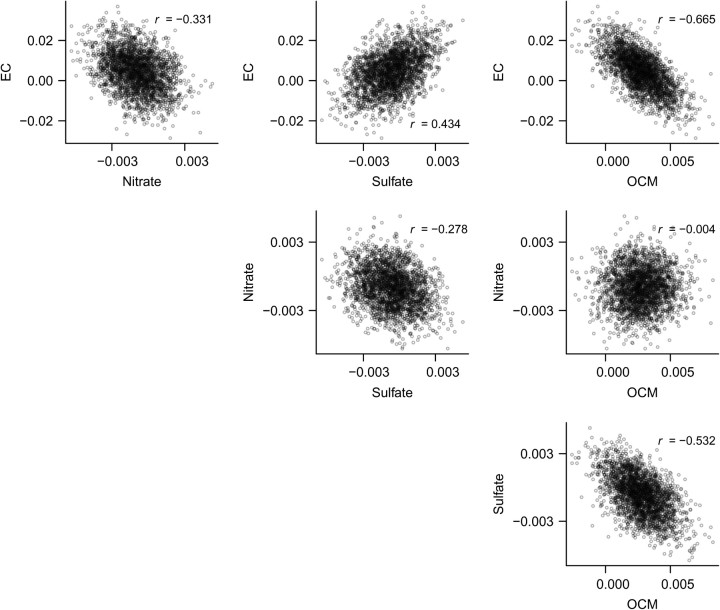

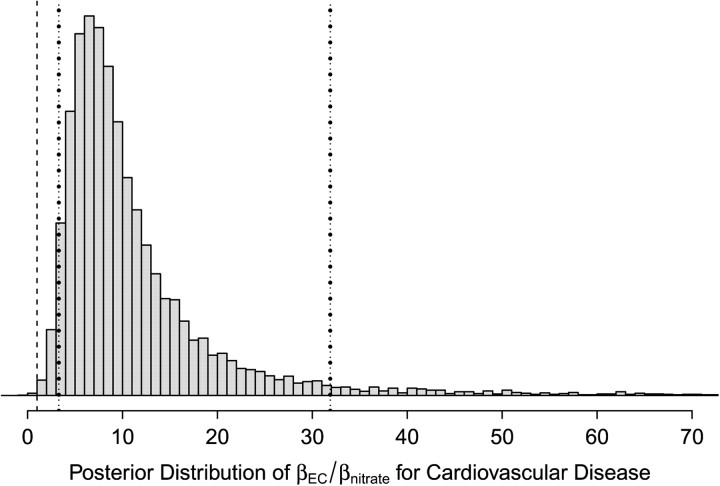

Our analyses also provide posterior correlations between CRFs for CHA (Figure 2) and RHA (Figure 3). Coupled with the posterior distributions from multiconstituent models in Figure 1, this would allow for the CRFs to be incorporated into risk assessments. The posterior samples also allow us to characterize the ratios of CRFs for different constituents, which have often been used to incorporate differential toxicity in risk assessments. Figure 4 provides the posterior distribution of the ratio of CRFs for elemental carbon versus nitrate for CHA. The nonnormality, skew, and long tails are immediately apparent. All distributions of toxicity ratios were quite uncertain, even when posterior probabilities of differential toxicity were close to 1.

Figure 2.

Scatterplots and correlations of posterior samples of beta coefficients per unit change in concentrations of fine particulate matter constituents for cardiovascular hospital admissions across the United States, 2000–2008. (EC, elemental carbon; OCM, organic carbon matter).

Figure 3.

Scatterplots and correlations of posterior samples of beta coefficients per unit change in concentrations of fine particulate matter constituents for respiratory hospital admissions across the United States, 2000–2008. (EC, elemental carbon; OCM, organic carbon matter).

Figure 4.

An example (elemental carbon (EC) vs. nitrate) of a posterior distribution of toxicity ratios for cardiovascular hospital admissions across the United States, 2000–2008. Also shown are the second percentile (x = 1; dashed line), the fifth percentile (x = 3.3; left dotted line), and the 95th percentile (x = 31.9; right dotted line) of the posterior distribution.

DISCUSSION

Our 2-pronged approach toward evaluating the differential toxicity of particle constituents provided some helpful insights and illustrated some barriers. First, our review showed that the present literature generally lacks multiconstituent models and other information necessary to determine the probability of differential toxicity. This may be due to statistical power issues and the fact that the goal of many investigations was to determine which constituents are more strongly associated with health outcomes, rather than to quantify their relative toxicity. In the absence of changes in how particle constituent epidemiology is generally conducted, even the expansion of this literature over time would not resolve the question of differential toxicity within risk assessment.

To our knowledge, our extended analysis of the national Medicare database is the largest multisite time-series analysis of PM2.5 constituents to have been conducted to date. We followed a multiconstituent modeling approach and applied the statistical methods necessary to determine correlations among CRFs and posterior probabilities of toxicity differences, providing the core information for risk assessment. We found some evidence of toxicity differences that vary by health outcome, with more limited evidence supporting geographic variability, partly because of statistical power issues in the West. In contrast, the primary approach for including differential toxicity in risk assessment to date has been assumptions that one constituent is X times more toxic than another (53, 54), applied as point estimates without formal consideration of the appreciable uncertainties that would exist. The ratios of 2 uncertain distributions will have even greater uncertainties—a well-described phenomenon in statistics and comparative risk assessment (55, 56)—but this has not been discussed in the context of PM2.5.

Although there are significant uncertainties in the probabilistic comparisons, epidemiology needs to provide the foundation for any differential toxicity analysis used in PM2.5 health risk assessments, given the need to quantify and potentially monetize specific health outcomes (e.g., emergency room visits). That having been said, creative approaches for incorporating insight from toxicology should be considered, including using toxicologic evidence as informative priors in a Bayesian analysis.

A few limitations within our extended Medicare analysis should be acknowledged. First, as described previously (8), we were limited by 1-in-6-day sampling and by the nonuniform distribution of speciation monitors. Second, our results could be affected by exposure measurement error due to the spatial variability of the ambient concentrations of each constituent within each county. Lastly, there may have been some error due to spatial misalignment and aggregation of the data, given that most counties have just 1 or 2 monitors (57).

In addition, the specific probabilities ascertained in our analysis should not be directly extrapolated to other health outcomes. The relative influence of different constituents may differ for acute responses versus chronic responses, and there could be differences across diseases and at-risk populations. Lack of statistical significance for specific constituents and endpoints should also be interpreted in the context of the broader literature, especially for RHA, for which rates are lower and statistical power is reduced in comparison with CHA. Interpretation of the effects of sulfate and nitrate is complicated by the strong association with ammonium. In the prior analysis of the Medicare data set, ammonium was associated with CHA, which likely reflects effects of correlated constituents like sulfate and nitrate (8). We excluded ammonium given our multiconstituent focus, which may have reduced our ability to characterize secondary inorganic aerosols. Our focus on lag 0 effects may have underestimated impacts, given prior evidence that organic carbon matter influences CHA at lag 1 and sulfate influences RHA at lags 1 and 2 (8). Finally, our analysis defined differential toxicity by the CRF for each constituent, “adjusted” for exposure to other constituents and time-varying confounders. While this matches most risk assessments, burden-of-disease studies may be more concerned with the effects per interquartile range, which would yield different conclusions and avoid complications related to variable contributions to mass.

In spite of these challenges, our methods are generalizable and could be applied within other data sets, and our findings provide helpful insights for future PM2.5 risk assessments and epidemiologic investigations. The methods we applied to estimate posterior probabilities of differential toxicity and correlations among CRFs could have been used in many previous studies. Posterior samples from the joint posterior distribution of the short-term effects of each constituent from a multiconstituent model can provide the necessary information to conduct risk assessments and appropriately account for significant correlations among constituents that exist in some settings. The lack of such applications may have reflected a lack of recognition among epidemiologists of the value of these calculations and among risk assessors that such information could be generated. Most risk assessments involve post hoc interpretation of the literature, often making assumptions necessitated by the limited information provided. More direct communication between risk assessors and epidemiologists could enhance the utility of epidemiologic evidence in risk assessment, especially for criteria air pollutants, where epidemiology is paramount.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Author affiliations: Department of Environmental Health, School of Public Health, Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts (Jonathan I. Levy); Department of Environmental Health, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts (Jonathan I. Levy); and Department of Biostatistics, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts (David Diez, Yiping Dou, Christopher D. Barr, Francesca Dominici).

This work was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (grants R01ES012054 and R01ES019560), the Environmental Protection Agency (grants RD-82341701 and RD-83479801), and the Federal Aviation Administration, through the Partnership for Air Transportation Noise and Emissions Reduction (Cooperative Agreements 07-C-NE-HU and 09-C-NE-HU).

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the funders.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CHA

cardiovascular hospital admission

- CI

confidence interval

- CRF

concentration-response function

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision

- PM2.5

particulate matter less than 2.5 μm in diameter

- RHA

respiratory hospital admission

References

- 1.Office of Air and Radiation, Environmental Protection Agency. The Benefits and Costs of the Clean Air Act: 1990 to 2020. Washington, DC: Environmental Protection Agency; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Office of Air and Radiation, Environmental Protection Agency. Regulatory Impact Analysis for the Proposed Federal Transport Rule. Washington, DC: Environmental Protection Agency; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reiss R, Anderson EL, Cross CE, et al. Evidence of health impacts of sulfate-and nitrate-containing particles in ambient air. Inhal Toxicol. 2007;19(5):419–449. doi: 10.1080/08958370601174941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Industrial Economics, Inc. Uncertainty Analyses to Support the Second Section 812 Benefit-Cost Analysis of the Clean Air Act. Cambridge, MA: Industrial Economics, Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Science Advisory Board, Environmental Protection Agency. Advisory on Plans for Health Effects Analysis in the Analytical Plan for EPA’s Second Prospective Analysis—Benefits and Costs of the Clean Air Act, 1990–2020. Washington, DC: Environmental Protection Agency; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franklin M, Koutrakis P, Schwartz P. The role of particle composition on the association between PM2.5 and mortality. Epidemiology. 2008;19(5):680–689. doi: 10.1097/ede.0b013e3181812bb7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dominici F, Peng RD, Bell ML, et al. Fine particulate air pollution and hospital admission for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. JAMA. 2006;295(10):1127–1134. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.10.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peng RD, Bell ML, Geyh AS, et al. Emergency admissions for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases and the chemical composition of fine particle air pollution. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(6):957–963. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Everson PJ, Morris CN. Inference for multivariate normal hierarchical models. J Roy Stat Soc B. 2000;62(2):399–412. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mar TF, Norris GA, Koenig JQ, et al. Associations between air pollution and mortality in Phoenix, 1995–1997. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(4):347–353. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson HR, Bremner SA, Atkinson RW, et al. Particulate matter and daily mortality and hospital admissions in the West Midlands conurbation of the United Kingdom: associations with fine and coarse particles, black smoke and sulphate. Occup Environ Med. 2001;58(8):504–510. doi: 10.1136/oem.58.8.504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atkinson RW, Fuller GW, Anderson HR, et al. Urban ambient particle metrics and health: a time-series analysis. Epidemiology. 2010;21(4):501–511. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181debc88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baccarelli A, Wright RO, Bollati V, et al. Rapid DNA methylation changes after exposure to traffic particles. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(7):572–578. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200807-1097OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beelen R, Hoek G, van den Brandt PA, et al. Long-term effects of traffic-related air pollution on mortality in a Dutch cohort (NLCS-AIR study) Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(2):196–202. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell ML, Ebisu K, Peng RD, et al. Hospital admissions and chemical composition of fine particle air pollution. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(12):1115–1120. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200808-1240OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brauer M, Ebelt ST, Fisher TV, et al. Exposure of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients to particles: respiratory and cardiovascular health effects. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2001;11(6):490–500. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burnett RT, Cakmak S, Brook JR, et al. The role of particulate size and chemistry in the association between summertime ambient air pollution and hospitalization for cardiorespiratory diseases. Environ Health Perspect. 1997;105(6):614–620. doi: 10.1289/ehp.97105614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chuang KJ, Chan CC, Su TC, et al. Associations between particulate sulfate and organic carbon exposures and heart rate variability in patients with or at risk for cardiovascular diseases. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49(6):610–617. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318058205b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark NA, Demers PA, Karr CJ, et al. Effect of early life exposure to air pollution on development of childhood asthma. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(2):284–290. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0900916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darrow LA, Klein M, Flanders WD, et al. Ambient air pollution and preterm birth: a time-series analysis. Epidemiology. 2009;20(5):689–698. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a7128f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delfino RJ, Tjoa T, Gillen DL, et al. Traffic-related air pollution and blood pressure in elderly subjects with coronary artery disease. Epidemiology. 2010;21(3):396–404. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181d5e19b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fairley D. Daily mortality and air pollution in Santa Clara County, California: 1989–1996. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107(8):637–641. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gehring U, Cyrys J, Sedlmeir G, et al. Traffic-related air pollution and respiratory health during the first 2 yrs of life. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(4):690–698. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.01182001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henneberger A, Zareba W, Ibald-Mulli A, et al. Repolarization changes induced by air pollution in ischemic heart disease patients. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(4):440–446. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holguin F, Flores S, Ross Z, et al. Traffic-related exposures, airway function, inflammation, and respiratory symptoms in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(12):1236–1242. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200611-1616OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klemm RJ, Lipfert FW, Wyzga RE, et al. Daily mortality and air pollution in Atlanta: two years of data from ARIES. Inhal Toxicol. 2004;16(suppl 1):131–141. doi: 10.1080/08958370490443213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipfert FW, Morris SC, Wyzga RE. Daily mortality in the Philadelphia metropolitan area and size-classified particulate matter. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2000;50(8):1501–1513. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2000.10464185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipfert FW, Baty JD, Miller JP, et al. PM2.5 constituents and related air quality variables as predictors of survival in a cohort of U.S. military veterans. Inhal Toxicol. 2006;18(9):645–657. doi: 10.1080/08958370600742946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lippmann M, Ito K, Nádas A, et al. Association of particulate matter components with daily mortality and morbidity in urban populations. Res Rep Health Eff Inst. 2000;(95):5–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luttmann-Gibson H, Suh HH, Coull BA, et al. Systemic inflammation, heart rate variability and air pollution in a cohort of senior adults. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67(9):625–630. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.050625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luttmann-Gibson H, Suh HH, Coull BA, et al. Short-term effects of air pollution on heart rate variability in senior adults in Steubenville, Ohio. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48(8):780–788. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000229781.27181.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maynard D, Coull BA, Gryparis A, et al. Mortality risk associated with short-term exposure to traffic particles and sulfates. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(5):751–755. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Metzger KB, Tolbert PE, Klein M, et al. Ambient air pollution and cardiovascular emergency department visits. Epidemiology. 2004;15(1):46–56. doi: 10.1097/01.EDE.0000101748.28283.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morgenstern V, Zutavern A, Cyrys J, et al. Atopic diseases, allergic sensitization, and exposure to traffic-related air pollution in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(12):1331–1337. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200701-036OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Neill MS, Veves A, Zanobetti A, et al. Diabetes enhances vulnerability to particulate air pollution-associated impairment in vascular reactivity and endothelial function. Circulation. 2005;111(22):2913–2920. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.517110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Neill MS, Veves A, Sarnat JA, et al. Air pollution and inflammation in type 2 diabetes: a mechanism for susceptibility. Occup Environ Med. 2007;64(6):373–379. doi: 10.1136/oem.2006.030023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ostro B, Feng WY, Broadwin R, et al. The effects of components of fine particulate air pollution on mortality in California: results from CALFINE. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(1):13–19. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ostro B, Lipsett M, Reynolds P, et al. Long-term exposure to constituents of fine particulate air pollution and mortality: results from the California Teachers Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(3):363–369. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ostro B, Roth L, Malig B, et al. The effects of fine particle components on respiratory hospital admissions in children. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(3):475–480. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ostro BD, Feng WY, Broadwin R, et al. The impact of components of fine particulate matter on cardiovascular mortality in susceptible subpopulations. Occup Environ Med. 2008;65(11):750–756. doi: 10.1136/oem.2007.036673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patel MM, Hoepner L, Garfinkel R, et al. Ambient metals, elemental carbon, and wheeze and cough in New York City children through 24 months of age. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(11):1107–1113. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200901-0122OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peel JL, Tolbert PE, Klein M, et al. Ambient air pollution and respiratory emergency department visits. Epidemiology. 2005;16(2):164–174. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000152905.42113.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sarnat JA, Marmur A, Klein M, et al. Fine particle sources and cardiorespiratory morbidity: an application of chemical mass balance and factor analytical source-apportionment methods. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(4):459–466. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarnat SE, Suh HH, Coull BA, et al. Ambient particulate air pollution and cardiac arrhythmia in a panel of older adults in Steubenville, Ohio. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63(10):700–706. doi: 10.1136/oem.2006.027292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwartz J, Dockery DW, Neas LM. Is daily mortality associated specifically with fine particles? J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 1996;46(10):927–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sinclair AH, Edgerton ES, Wyzga R, et al. A two-time-period comparison of the effects of ambient air pollution on outpatient visits for acute respiratory illnesses. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2010;60(2):163–175. doi: 10.3155/1047-3289.60.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsai FC, Apte MG, Daisey JM. An exploratory analysis of the relationship between mortality and the chemical composition of airborne particulate matter. Inhal Toxicol. 2000;12(suppl 2):121–135. doi: 10.1080/08958378.2000.11463204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Villeneuve PJ, Burnett RT, Shi Y, et al. A time-series study of air pollution, socioeconomic status, and mortality in Vancouver, Canada. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2003;13(6):427–435. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zanobetti A, Schwartz J. Air pollution and emergency admissions in Boston, MA. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(10):890–895. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.039834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anderson HR, Armstrong B, Hajat S, et al. Air pollution and activation of implantable cardioverter defibrillators in London. Epidemiology. 2010;21(3):405–413. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181d61600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bell ML, Dominici F, Ebisu K, et al. Spatial and temporal variation in PM2.5 chemical composition in the United States for health effects studies. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(7):989–995. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spadaro JV, Rabl A. Damage costs due to automotive air pollution and the influence of street canyons. Atmos Environ. 2001;35(28):4763–4775. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rabl A, Spadaro JV. Public health impact of air pollution and implications for the energy system. Ann Rev Energy Environ. 2000;25:601–627. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Committee on Improving Risk Analysis Approaches Used by the U.S. EPA, National Research Council. Science and Decisions: Advancing Risk Assessment. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Finkel AM. Toward less misleading comparisons of uncertain risks: the example of aflatoxin and alar. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103(4):376–385. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peng RD, Bell ML. Spatial misalignment in time series studies of air pollution and health data. Biostatistics. 2010;11(4):720–740. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxq017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.