Abstract

Density functional theory and Natural Bond Orbital analysis are used to explore the impact of solvent on hyperconjugation in methyl triphosphate, a model for “energy rich” phosphoanhydride bonds, such as found in ATP. As expected, dihedral rotation of a hydroxyl group vicinal to the phosphoanhydride bond reveals that the conformational dependence of the anomeric effect involves modulation of the orbital overlap between the donor and acceptor orbitals. However, a conformational independence was observed in the rotation of a solvent hydrogen bond. As one lone pair orbital rotates away from an optimal anti-periplanar orientation, the overall magnitude of the anomeric effect is compensated approximately by the other lone pair as it becomes more anti-periplanar. Furthermore, solvent modulation of the anomeric effect is not restricted to the anti-periplanar lone pair; hydrogen bonds involving gauche lone pairs also affect the anomeric interaction and the strength of the phosphoanhydride bond. Both gauche and anti solvent hydrogen bonds lengthen non-bridging O—P bonds, increasing the distance between donor and acceptor orbitals, and decreasing orbital overlap which leads to a reduction of the anomeric effect. Solvent effects are additive with greater reduction in the anomeric effect upon increasing water coordination. By controlling the coordination environment of substrates in an active site, kinases, phosphatases and other enzymes important in metabolism and signaling, may have the potential to modulate the stability of individual phosphoanhydride bonds through stereoelectronic effects.

Keywords: phosphoryl transfer, anomeric effect, hyperconjugation, hydrogen bond, water, ATP

Introduction

ATP is vital to energy exchange in biological systems. The free energy liberated in the hydrolysis of ATP derives from “energy-rich” phosphoanhydride bonds that are essential for maintaining life.1 While crystallography,2–4 biochemical kinetics,5–8 thermodynamic studies 9,10 and computation11–13 have all furthered the understanding of phosphate ester hydrolysis, the chemical basis of “high-energy” or “energy-rich” O—P bonds continues to be debated.14–16 Our incomplete description of phosphanhydride chemistry in molecules, such as ATP and phosphocreatine (PC),17 limits our understanding of the enzymology of phosphoryl transfer in a wide variety of kinases and phosphatases, like creatine kinase, myosin and other ATPases.

The lability of the O—P bond is traditionally attributed to three factors:1,18 relative stability of the hydrolyzed products, due to reduced resonance stabilization,19 and greater electrostatic repulsion20 together with diminished solvation21 in the reactants. However, the nature of the O—P phosphoanhydride bonds in ATP has been re-evaluated recently and stereoelectronic effects were found to be significant.17,22 An anomeric effect appears to be more important than other delocalization interactions in the length and implied strength of O—P bonds.17

The O—P bond is destabilized or lengthened by a specific type of hyperconjugation that is popularly referred to as the anomeric effect.17 Anomeric interactions have been found to be maximal when the donor orbital is anti-periplanar to the vicinal bond, so that the donor orbital is in close proximity to the antibonding orbital of the neighboring bond for efficient electron density transfer between the two.23–25 One such interaction in a triphosphate is shown in Figure 1. The lone pair (donor) on a gamma oxygen interacts with the antibonding orbital (acceptor) of the sigma bond between the gamma phosphorous and the adjacent beta oxygen, and is denoted as the n(Oγ) → σ*(Oβ—Pγ) hyperconjugation. The term “anomeric effect” has been used to describe stereo-preferences of sugars26 and related molecules.27 Recent work has argued that stereo-preferences are actually a result of destabilizing electrostatic interactions.28 In this work the role of hyperconjugation in phosphodiester bond length is explored. The current terminology of describing some of the interaction as an “anomeric effect” is used following prior suggestions that the hyperconjugation was similar to that thought earlier to be a determinant of sugar conformation. In following this historical terminology, no implications are intended about the actual determinants of sugar conformation.

Figure 1.

Anomeric effect given by anti-periplanar alignment of n(Oγ) → σ*(Oβ—Pγ). The orbitals are colored green and purple with arbitrary phase.

Strain of a substrate towards the ideal anti-periplanar dihedral angle that maximizes the anomeric effect and destabilizes the bond has been proposed as a potential mechanism of enzyme catalysis, termed torsional activation. Gorenstein et al. explored the effects of anomeric bond destabilization in the formation of peptide N—C bonds in the gas phase reaction between ammonia and formic acid, chosen to model serine proteases.29 The study revealed that a lone pair on the hydroxyl oxygen, which is anti-periplanar to the attacking nitrogen, stabilized the transition state by 3.9 kcal/mol. They also examined O—P bond reactivity in the gas phase: in the dimethyl phosphate monoanion, there is a weakening by ~1 kcal/mol when oxygen atom lone pairs are anti-periplanar toward the bond versus gauche.30

A majority of quantum calculations have been performed in vacuo, inherently omitting environmental effects that could conceivably modulate stereoelectronic effects.31–34 The effect of solvent on conformational energetics was demonstrated in quantum studies of the phosphodiester links of DNA.35 In NMR-restrained molecular dynamics studies of DNA and the DNA-binding domain of the transcription activator protein, PhoB, it was found that the solution structure provided better local geometry and convergence then structures determined in vacuum.36 Recent studies with implicit solvent found strong correlations between the anomeric effect and O—P and N—P bond lengths in analogs of nucleotides and phosphocreatine.17,37 A reduction in anomeric effect was observed when lone pair donor ability was decreased (with solvent) or the electron density acceptor ability of the anti-bonding acceptor was decreased.

The influence of environmental factors or conformation upon the anomeric effect remains an open question germane to potential enzyme mechanisms.17,29,37,38 Yang et al. recently used QM/MM calculations to analyze ATP in the open (post-rigor) and closed (pre-powerstroke) active sites of the myosin motor domain.38 Despite a substantial difference in the scissile O—P bond length (0.05 Å), Arg238, the residue with the largest effect on the anomeric interaction, had only modest impact on the ground state energy. Rudbeck et al. used a similar approach to look at the environmental impact of the Ca2+-ATPase on its phosphoenzyme intermediate and found that in the inactive protein model, the NH3 group of Lys684 induces shortening of the P−Oβ bond due to changes in hyperconjugation, while in the inactive model, the P—Oβ bond is elongated.39 Both of these studies looked at destabilization of the ground state, however, other potential catalytic effects, such as transition state stabilization, remain to be investigated. Although hyperconjugation lengthens the scissile bond, paradoxically, it also stabilizes the molecule as a whole. Potentially then, hyperconjugation could lower the energy of the transition state while also destabilizing the scissile bond.

The rationale for analyzing hydrogen-bonding interactions stems from our prior finding that the anomeric effect depends on protonation state of the γ-phosphate in methyl triphosphate.17 Involvement of the gamma phosphate oxygen lone pair in a hydrogen bond reduces the electron density available for transfer in an anomeric interaction.17 The potential importance of hydrogen bonding interactions was also highlighted by Iche-Tarret et al. who found that an intramolecular hydrogen bond in protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTPase) substrate analogs destabilized the scissile O—P bond.40 In an enzyme active site, both protein and solvent atoms could form relevant hydrogen bonds, but interactions with water molecules are of particular interest. A number of kinases undergo large conformational changes, to exclude water from the active site, perhaps to prevent premature hydrolysis of the ATP substrate.41 By contrast, the active sites of some enzymes contain water molecules in conserved locations 42 that can have multiple roles in catalysis.43–45 Thus, we chose the interactions of water with methyl triphosphate both as a general model for the interactions of polar groups with phosphoanhydride bonds, and also to provide insights into the diverse roles of water upon hyperconjugation in phosphoryl transfer active sites.

Despite its crucial role in physiological processes, the factors governing O—P phosphoryl bond weakening and possible connection to ”high energy” character of phosphates remains controversial.46–50 The current work explores how molecular conformation and solvent interactions impact ground state O—P bond weakening through stereoelectronic effects. We show that water can have a strong impact on phosphoanhydride bond length. Changes to the solvation upon substrate-binding, and, by inference, hydrogen bonding with other polar active site groups, have the capacity to alter significantly the energetics of catalysis, and the specificity of which phosphoanhydride bond would be destabilized in a particular enzyme-catalyzed reaction.

Methods

Electronic structure calculations were carried out with the Gaussian 09 suite.51 The B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level of theory was used for structure optimization.38,52–54 Prior studies17 showed that this level of theory captured the same hyperconjugative effects as second-order Moller-Plesset55 computations. In addition to the water molecules explicitly modeled, the effects of bulk solvent were modeled implicitly using a polarizable continuum model (PCM).56

Combining explicit waters with continuum approach such as PCM can lead to inaccuracies in handling the polarization of the first solvation shell and entropic terms in free energy calculations.57 However for potential energy calculations used to assess enthalpies of explicit interactions, a mixed model has been shown to be an appropriate treatment.58 Thus, in this work, nearest-neighbor explicit water molecules are embedded in a continuum approximation.59

Natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis was performed using the GenNBO5 program60 with output files from the Gaussian 09 program. HF/cc-PVTZ model chemistry was used for all NBO calculations upon B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) geometry optimized structures.61 NBO transforms the non-orthogonal atomic orbitals from the HF wavefunction into natural bond orbitals (NBO)62 allowing for a Lewis-like description of the total N-electron density63. Delocalizing interactions can be treated through second-order perturbation theory. The E(2) energy values provide an estimate of the magnitude of delocalizing interactions and are calculated by64

| (1) |

where qi is the donor occupancy. The difference in energy of the donor and acceptor orbitals is E(j)−E(i) and the orbital interaction energy is F(i,j). Orbital interaction energy, also known as the Fock matrix element, is a reflection of orbital overlap between orbitals i and j. For the purposes of this work, the donor orbital, j, will always be the lone pair orbitals on Oγ, and the acceptor orbital, i, is the σ*(O3β—Pγ) antibonding orbital in the methyl triphosphate model of ATP (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Orientation of lone pairs. a) Lewis structure of methyl phosphate triester. b) Corresponding Newman projection. The O3β—Pγ—O3γ—X dihedral (highlighted in red) was rotated from −60° to 60° to change the orientation of lone pairs with respect to the σ*(O3β—Pγ) anti-bonding orbital. c) X represents either a proton (structure 1) or a hydrogen bond donated by water (structure 2).

Methyl triphosphate has previously been employed as a simplified model for the study of hyperconjugative interactions in ATP.17,65 Structures 1 and 2 were used to examine the effects of lone pair position on anomeric energy and O3β—Pγ bond length through rotation of the neighboring dihedral angles (Figure 2, shown in red). As each dihedral angle (∠O3β—Pγ—O3γ—X) was scanned, all other parameters of the structure were optimized, except in structure 2 where the O3γ•••OH2 hydrogen bond length was held constant at a typical 2.6 Å.66 For structure 1, where one of the γ-oxygens is protonated, the O3β—Pγ—O3γ—H dihedral angle was rotated from −60° to 60° in 10° increments. The O3β—Pγ—O3γ•••OH2 dihedral angle in structure 2, was rotated from −60° to 60° in 20° increments. Changes in bond length, E(2) energy, interaction energy and orbital energy gap were measured with reference to the values calculated for the staggered rotamers (∠O3β—Pγ—O3γ—X = 180°). Throughout the text, lone pairs are labeled 1 or 2 to make referencing the lone pairs as they rotate around the O3β—Pγ—O3γ—X dihedral angle more convenient. Only lone pairs that have n(Oγ) → σ*(O3β—Pγ) E(2) energies that are greater than the NBO program default cutoff of 0.5 kcal/mol are discussed in this study.

The effects of different hydrogen bonding configurations were explored with structures 3 through 10 (Figure 3), which were built using GaussView5.0. Structures were then optimized while constraining the O3β—Pγ—O3γ⋯H(OH) and O3β—Pγ—O3γ⋯O(H2) dihedral angles to fixed 180° or 90° values (both the oxygen and relevant hydrogen of water are fixed relative to O3β—Pγ). The O3γ⋯OH2 distance was again fixed at 2.6 Å and all other parameters were allowed to relax. All changes are measured in reference to structure 3, methyl triphosphate without explicit waters. The effects of hydrogen bond length were examined using structure 4. As the donor-acceptor distance was increased from 2.4 Å, other structural parameters were optimized, with the exception of the O3β—Pγ—O3γ⋯H(OH) and O3β—Pγ—O3γ⋯O(H2) dihedral angles which were held at 180° in the anti-conformation.

Figure 3.

Eight structures with different hydrogen bonding configurations were used in a detailed examination of the effects of hydrogen bonding on phosphodiester bonds. Structure 3 has no hydrogen bonding interactions and serves as a reference. Waters are placed at a O3β—Pγ—Oγ•••OH2 dihedral angle of 180° or 90° as depicted in red in the Newman projections above each column of structures. White = hydrogen, grey = carbon, red = oxygen, yellow = phosphorus.

Results and Discussion

The effects of lone pair alignment on hyperconjugation and bond lengths in methyl triphosphate

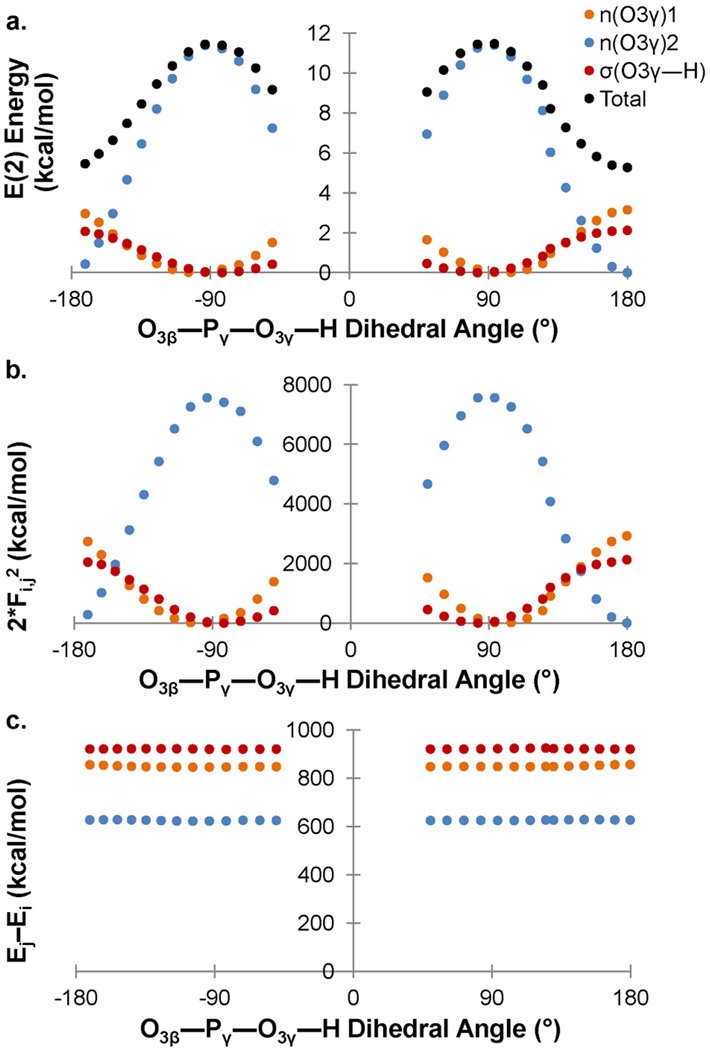

The anomeric effect is classically thought of as highly dependent on optimal orbital alignment of lone pair and antibonding orbitals.67,68 Thus, the anomeric interaction, n(Oγ) → σ*(O3β—Pγ) is expected to be diminished by rotation of n(Oγ) out of the anti-periplanar position. To characterize the influence of the anomeric effect on the O3β—Pγ bond in methyl triphosphate, orbital occupancies, E(2) energies and O3β—Pγ bond length were calculated as a function of torsional rotation of the O3β—Pγ—O3γ—H dihedral angle in structure 1 (Figure 2). To understand the basis of variation in anomeric energy, E(2) energy was broken down into its components of interaction energy, Fij and orbital energy gap, Ej−Ei (Equation 1), both as a function of the O3β—Pγ—O3γ—H dihedral angle.

The anomeric energy is found to be highly correlated with the O3β—Pγ bond length (R2 = 0.92, Figure 4). A parallel increase was observed in the anti-bonding orbital occupancy with a correlation between occupancy and bond length of R2 = 0.98. If the changes in O3β—Pγ were due to inductive withdrawal into the Pγ—O3γ bond, decrease in the O3β—Pγ bonding orbital occupancy would be expected. However, the occupancy was independent of the O3β—Pγ—O3γ—H rotation, suggesting that the observed change in bond length does not result from an inductive effect.

Figure 4.

a) Calculated E(2) hyperconjugative energies and O3β—Pγ bond lengths for rotamers of structure 1. Changes are measured with reference to ∠O3β—Pγ—O3γ—H = 180°. b) Correlation between O3β—Pγ bond length and σ*(O3β—Pγ) orbital occupancy.

The anomeric effect is maximal when lone pair 2 is anti-periplanar to O3β—Pγ and the proton is at a 90° dihedral angle relative to O3β—Pγ (Figure 5). At this orientation of the hydroxyl group, lone pair 2 accounts for almost 100% of the total E(2) with σ*(O3β—Pγ) (Figure 5a, blue line). The, the overall change in E(2) energy (Figure 5a, black line) with angular rotation occurs because lone pair 2 is a much stronger electron density donor than both lone pair 1 and σ(O—H) combined. Lone pair 2 is readily able to donate electron density because of its smaller orbital energy gap with the σ*(O3β—Pγ) orbital (ca. 600 kcal.mol) as compared to the gap between σ*(O3β—Pγ) and lone pair 1 or between σ*(O3β—Pγ) and σ(O3γ—H) (both ca. 900 kcal/mol, Figure 5c). Furthermore, the maximum orbital overlap between σ*(O3β—Pγ) and lone pair 2 is more than twice the maximum orbital overlap between σ*(O3β—Pγ) and lone pair 1 or between σ*(O3β—Pγ) and σ(O3γ—H). Together the relatively lower orbital energy gap and higher interaction energy of lone pair 2 with σ*(O3β—Pγ) dictate a 6 kcal/mol increase in E(2) energy at ∠O3β—Pγ—O3γ—H = 180° over ∠O3β—Pγ—O3γ—H = 90°. This change in E(2) energy is mirrored by a 0.012 Å increase in O3β—Pγ bond length.

Figure 5.

a) E(2) energy shows a strong angular dependence for rotation of the O3β—Pγ—O3γ—H dihedral angle. b) The orbital overlap, as mirrored in the numerator of equation 1, 2Fij2 and c) the energy gap for the hyperconjugative interaction with σ*(O3β—Pγ) and lone pairs n1(O3γ) (orange), n2(O3γ) (blue) or σ(O—H) (red).

Consistent with previous reports, our study demonstrates that hypercongugative n(O) → σ*(O—P) interactions are prominent in the lengthening / weakening of vicinal O3β—Pγ bonds. There is indeed an anomeric component to the interaction, the O3β—Pγ bond length changing 0.01 Å, dependent on the orientation of the donating lone pair relative to the anti-bonding orbital. Unique to this study is that changes in hyperconjugation, while dependent on the orbital energy gaps, are most responsive to changes in interaction energy, as mirrored in the numerator of Equation 1, 2Fij2.

Hyperconjugative bond lengthening is independent of solvation geometry

Hyperconjugative interactions have previously been calculated for dihydrogen- and metaphosphate interactions with waters, where there is strong donation of electron density from the dihydrogen-or metaphosphate oxygen lone pairs into the σ*(O—H) anti-bonding orbital of water.69 Thus, it might be expected that water would withdraw electron density from the lone pairs in methyl triphosphate, thus weakening the n(Oγ) → σ*(O3β—Pγ) interaction. Indeed addition of a hydrogen bond between water and O3γ of methyl triphosphate (structure 4 in Figure 3) is accompanied by a 0.017 Å decrease on O3β—Pγ bond length and a 4.8 kcal/mol reduction in E(2) energy. As a 0.01 Å change in bond length was induced in structure 1 through rotation of the OPOH dihedral angle, it was hypothesized that analogous rotation of the water would induce corresponding changes in bond length. To test this, the O3β—Pγ—O3γ•••OH2 dihedral angle in structure 2 (Figure 2) was rotated in increments of 20° from −60° to +60° (see Methods).

Solvent hydrogen bonds oriented at 90° or 180° with respect to O3β—Pγ induce similar perturbations in O3β—Pγ bond lengths, differing by only 0.003 Å (Figure 6). Likewise total E(2) interaction energies are similar (E(2) for n(O3γ) → σ*(O3β—Pγ) differing by 2.2 kcal/mol). Thus, the orientational dependence of the hydrogen-bonded system is about one third that of the protonated system. In the solvated system, each of the two higher energy O3γ lone pair orbitals can have a similar E(2) interaction if anti-periplanar to σ*(O3β—Pγ), as shown in Figure 6b. With dihedral rotation of the lone pairs about O3β—Pγ (as they follow the scanned direction of the water hydrogen bond), the change in one E(2), as the orbital rotates away from an optimal anti-periplanar orientation, is compensated approximately by the change in the other as it becomes more anti-periplanar. Which of these lone pairs is participating in a hydrogen bond has relatively little impact, because, as discussed below, both lone pair orbital interactions are affected by the presence of the water simultaneously, without much directional specificity, and to a degree that had not been anticipated.

Figure 6.

Orientation of a hydrogen bond from water relative the O3β—Pγ bond has little impact on O3β—Pγ bond length. a) Neither the O3β—Pγ bond length or E(2) energy vary greatly as a function of O3β—Pγ—O3γ•••OH2 dihedral angle. The maximal change in bond length is only 0.003 Å and in E(2) energy is only 2 kcal/mol. b) When one lone pair orbital rotates away from an optimal anti-periplanar orientation, the other improves. The E(2) energies are nearly symmetric, in spite of the fact that a water is interacting with lone pair 2 (orange), but not 1 (blue).

Water interactions can decrease orbital overlap of additional lone pairs with σ*(O3β—Pγ)

The difference in orbital interactions are shown in Figure 7. When ∠O3β—Pγ—O3γ•••OH2 = 90°, it is the non-hydrogen bonded n(O3γ)1 that contributes 100% of the O3γ E(2) energy (Figure 6). As there is not a direct interaction between n(O3γ)1 and the hydrogen bond from water (Figure 7c), it was surprising that the E(2) energy was affected by the presence of the water. This led to a broader analysis of the electronic differences between conformers with ∠O3β—Pγ—Oγ•••OH2 = 180° and 90°. Analysis started with a study of E(2) energy as a function of the number of Oγ hydrogen bonds (Figure 8) for structures 3 through 7, 9 and 10 (Figure 3).

Figure 7.

Images of the O3γ lone pairs 1 and 2 from figure 6b at a) O3β—Pγ—O3γ•••OH2 = 180° and b) O3β—Pγ—O3γ•••OH2 = 90°. Water is always coordinated to lone pair 2 (colored orange in parts b and d). In a) water interacts with lone pair 2, which in this configuration, is anti-periplanar to O3β—Pγ whereas in b) water interacts with lone pair 2 which is at a 90° angle to O3β—Pγ. When lone pair 2 is at 90°, it contributes nothing to the overall E(2) energy of n(Oγ) → σ*(O3β—Pγ). However, the E(2) energy of n(Oγ) → σ*(O3β—Pγ) and the O3β—Pγ bond length are similar in both orientations. Atoms are colored; white (hydrogen), grey (carbon), yellow (phosphorus) and red (oxygen). The orbital lobes of the lone pairs on O3γ are colored red and green, depicting opposite polarities.

Figure 8.

Waters coordinated at 180° (a – d) or 90° (e – f) from the O3β—Pγ bond both decrease (a, e) O3β—Pγ bond length and (b, f) hyperconjugation between γ-oxygen lone pairs and the σ*(O3β—Pγ) anti-bonding orbital. Open triangles represent values of hyperconjugative interactions where there is no hydrogen bond. Closed triangles represent values where there is a hydrogen bond. (c, g) In both orientations, water reduces 2Fij2 relative to structure 3, water-free methyl triphosphate. (d, h) However only structures with waters at 180° show a pronounced change in orbital energy gap. This discrepancy accounts for the slightly larger depression in O3β—Pγ bond length for structures with waters at 180°. Only orbitals in the anti-periplanar orientation contribute to E(2) energy and thus values for the other two orbitals on each oxygen were not plotted.

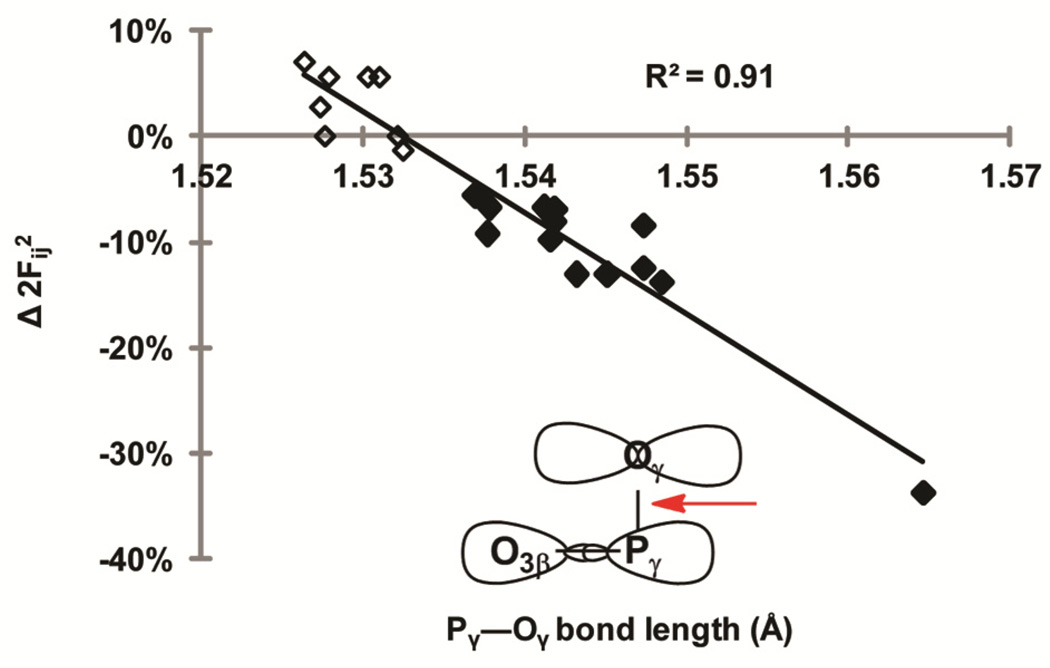

In Figure 8, O3β—Pγ bond length, E(2) energy, and its components 2Fij2 and Ej−Ei of the of n(Oγ) → σ*(O3β—Pγ) hyperconjugative interaction are plotted against number of waters coordinated to γ-oxygen lone pairs. Figure 8a–d represents structures 4, 6 and 9 (Figure 3) where the water is hydrogen bonded to the lone pair that is anti-periplanar to O3β—Pγ (Figure 7a). Figure 8e–f represents structures 5, 7 and 10 where the water is bound to the lone pair that is offset by 90° and is thus not participating in the n(Oγ) → (O3β—Pγ) hyperconjugative interaction (Figure 7c). There are only small differences in O3β—Pγ bond length and E(2) values for structures with hydrogen bond(s) oriented at ∠O3β—Pγ—Oγ•••OH2 = 180° (Figure 8a) versus ∠O3β—Pγ—Oγ•••OH2 = 90° (Figure 8e). For example, a hydrogen bond with the anti-periplanar lone pair relative to the O3β—Pγ bond induces a decrease in the O3β—Pγ bond length by about 0.02 Å, and with three waters, O3β-Pγ is shortened by about 0.06 Å. When the hydrogen bond is offset 90°, these values are only slightly less (0.015 Å and 0.04 Å respectively). Similarly the addition of a hydrogen bond at ∠O3β—Pγ—Oγ•••OH2 = 180° induces a decrease in E(2) energy of about 6 kcal/mol (Figure 8b). If the hydrogen bond is at ∠O3β—Pγ—Oγ•••OH2 = 90° the reduction in E(2) is closer to 4 kcal/mol (Figure 8f). Particularly striking is the relative similarity of plots c and g in Figure 8. It had been expected that a water would only affect the orbital with which it is hydrogen-bonded. However we find that the 2Fij2 terms, are decreased for both orbitals 1 and 2 regardless of hydrogen bond orientation by roughly 10%.

In a first (unsuccessful) attempt to rationalize direction-independent changes to Fij2, we examined how hydrogen-bonding might affect hybridization of orbitals not directly participating in the hydrogen bond. A lone pair starting with 99.7% p-character gains 8.9% s-character on hydrogen bonding, but other lone pairs are affected negligibly (< 0.02%). Thus, direction-independent effects do not appear to result from widespread changes in hybridization.

Hydrogen bonding lengthens the non-bridging Pγ—Oγ bond of the coordinated oxygen (Figure 9). An increase in the Pγ—Oγ bond length physically increases the distance between the lone pair orbitals on Oγ and the σ*(O3β—Pγ) anti-bonding orbital (Figure 9, inset) thus decreasing their overlap. This explains computed changes to Fij2 that are independent of the direction of hydrogen bonding, because all hydrogen bonds to the Oγ increase the Pγ—Oγ bond length. Consistent with this rationalization, there is a strong correlation between Δ2Fij2 and Pγ—Oγ bond lengths for structures 4 through 10 (R2 = 0.90).

Figure 9.

For structures 4 through 10, there is a strong correlation between Δ2Fij2 of the interaction n(Oγ) → (O3β—Pγ) and non-bridging Pγ—Oγ bond length. Changes are measured relative to structure 3. Open diamonds represent Pγ—Oγ bond lengths where there is no hydrogen bond with Oγ. Closed diamonds represent Pγ—Oγ bond lengths where there is a hydrogen bond with Oγ. Inset: the schematic highlights (red arrow) the bond that is lengthened indirectly by any configuration of hydrogen bond to Oγ, thereby affecting the proximity and overlap of the Oγ, lone pair orbitals and the σ*(O3β—Pγ) anti-bonding orbital.

Two hydrogen bonds with a single oxygen has the same effect as two hydrogen bonds with two different oxygens

The change in O3γ—Pγ bond length is linearly proportional to the number of hyperconjugation-modulating solvent hydrogen bonds on different oxygens (Figure 8). It has also been shown that changes in the n(Oγ) → (O3β—Pγ) hyperconjugative interaction are not greatly dependent on the direction of hydrogen bonding. Thus, the effects on E(2) energy and bond length of two hydrogen bonds on the same oxygen, one at 180° and one at 90°, might be expected to be additive. This postulate was examined by comparing structures 6, 7 & 8 with structure 3. Unlike the desolvated structure 3, structures 6, 7 & 8 are coordinated by two waters. In structures 6 & 7, the waters are coordinated to different oxygens, but in structure 8, both waters interact with the same γ-oxygen. The O3β—Pγ bond lengths (and relevant E(2) energies) of structure 6, 7 and 8 are very similar to each other but different from structure 3 (Table 1). Thus, whether interacting with the same or different γ-phosphate oxygens, the effects of multiple hydrogen bonds are, to a first approximation, additive and independent of orientation relative to the σ* orbital. This is of potential enzymological significance, because an oxygen of an ATP bound in an active site can have multiple hydrogen-bonding interactions.70–73 The effects of all upon catalysis will need to be integrated, not just interactions with lone pairs anti-periplanar configuration to σ*.

Table 1.

O3β—Pγ Bond lengths and n(Oγ) → σ*(O3β—Pγ) E(2) energies of structures 3, 6, 7 and 8.

| structure | O3β—Pγ bond length |

total E(2) of n(Oγ) → σ*(O3β—Pγ) |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | 1.742 | 90.6 |

| 6 | 1.700 | 79.8 |

| 7 | 1.711 | 83.3 |

| 8 | 1.711 | 81.9 |

Dependence on the Strength of the Hydrogen Bond

The strength of the hydrogen bond interaction was modulated by changing the constrained hydrogen bond length in structure 4. With a hydrogen bond length of 2.4 Å, the O3β—Pγ bond is 1.718 Å, 0.024 Å shorter than without a water molecule (structure 3). The calculated change in phosphodiester bond energy due to loss of a 2.4 Å-hydrogen bond is approximately 21 kcal/mol. (Thus the loss of two hydrogen bonds would be commensurate with the ~40 kcal/mol empirically measured activation barriers of representative phosphoryl transfer enzyme reactions) 74–78 The O3β—Pγ bond length increases by ~ 0.02 Å per Å increase in the hydrogen bond length (Figure 10). At a hydrogen-acceptor distance of 3.4 Å, the hydrogen bond has negligible impact upon the O3β—Pγ bond length and E(2) energy of n(Oγ) → σ*(O3β—Pγ) interaction. Hydrogen bonds are usually considered to have both electronic and classical electrostatic components.79,80 The 3.4 Å limit on modulation of the ATP stereoelectronics is consistent with the understanding that the covalent component of a hydrogen bond decreases with distance.

Conclusion

It is increasingly clear that interactions between lone pair orbitals and anti-bonding orbitals are central to the properties of several high energy molecules of biochemical importance. Earlier characterizations focused on anomeric effects where the lone pair orbitals were optimally aligned for interaction with the σ* acceptor orbital.

Here, it is shown that considerable conformational variation can be accommodated: the effects of coordinating to the anti-periplanar and gauche lone pairs are similar in their reduction of the E(2) anomeric interaction and in decreasing the length of the vicinal phosphoanhydride bond. Interactions with the lone pairs modulate the anomeric effect largely through lengthening of non-bridging P—O bonds which changes the overlap between all lone pair orbitals on the coordinated oxygen and the σ* anti-bonding orbital, and this, in turn, affects the Fock interaction energy.

The significance of this finding is that a larger set of enzyme-substrate and solvent-substrate interactions needs to be considered in assessing environmental modulation of phosphoanhydride bond lability. Coordination of lone pairs, not only in the anti-periplanar direction, but also in gauche directions, has nearly the same potential to lessen an anomeric effect and conjointly stabilize the vicinal phosphoanhydride. Loss of such interactions by desolvation, as a substrate binds in an active site, could be one of the means with which an enzyme could destabilize the scissile bond in phosphoryl transfer reactions. It is also one of the ways that an enzyme could modulate the relative stability of the different phosphoanhydride bonds in a nucleotide, potentially impacting product specificity. Thus the investigation here lays a foundation for improving our mechanistic understanding of the kinases and phosphatases that play critical roles in energy metabolism, cellular motility and signaling.

Supplementary Material

Figure 10.

Effect of hydrogen bond length, Oγ⋯H(OH) on O3β—Pγ bond length for structure 8.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by NIH R01GM77643 (MSC) and by pre-doctoral fellowships from the American Heart Association (Pacific Mountain Affiliate, predoctoral fellowship 09PRE2020112) and Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc. (JCS). The authors thank Dr. Omar Davulcu for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Gaussian archives for all structures at B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Berg J, Tymoczko JL, Stryer L. Biochemistry. 5th ed. New York: W.H. Freeman & Co.; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siebold C, Arnold I, Garcia-Alles LF, Baumann U, Erni B. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:48236. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305942200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Srivastava SK, Rajasree K, Gopal B. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1814:1349. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yousef MS, Fabiola F, Gattis JL, Somasundaram T, Chapman MS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2002;58:2009. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902014683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu M, Dobson B, Glicksman MA, Yue Z, Stein RL. Biochemistry. 2010;49:2008. doi: 10.1021/bi901851y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu M, Girma E, Glicksman MA, Stein RL. Biochemistry. 2010;49:4921. doi: 10.1021/bi100244j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneck JL, Briand J, Chen S, Lehr R, McDevitt P, Zhao B, Smallwood A, Concha N, Oza K, Kirkpatrick R, Yan K, Villa JP, Meek TD, Thrall SH. Biochemistry. 2010;49:7151. doi: 10.1021/bi100824v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ullrich SJ, Hellmich UA, Ullrich S, Glaubitz C. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:263. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olson AL, Cai S, Herdendorf TJ, Miziorko HM, Sem DS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:2102. doi: 10.1021/ja906244j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stockbridge RB, Wolfenden R. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:22747. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.017806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szarek P, Dyguda-Kazimierowicz E, Tachibana A, Sokalski WA. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:11819. doi: 10.1021/jp8040633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valiev M, Yang J, Adams JA, Taylor SS, Weare JH. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:13455. doi: 10.1021/jp074853q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinreb V, Li L, Campbell CL, Kaguni LS, Carter CW., Jr Structure. 2009;17:952. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dittrich M, Hayashi S, Schulten K. Biophys. J. 2003;85:2253. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74650-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knowles JR. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1980;49:877. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.004305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill TL, Morales MF. Arch. Biochem. 1950;29:450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruben EA, Plumley JA, Chapman MS, Evanseck JD. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:3349. doi: 10.1021/ja073652x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Voet D, Voet JG. Biochemistry. 3rd Edition ed. Wiley: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wheland GW. The Theory of Resonance. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill TL, Morales MF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951;73:1656. [Google Scholar]

- 21.George P, Witonsky RJ, Trachtman M, Wu C, Dorwart W, Richman L, Richman W, Shurayh F, Lentz B. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1970;223:1. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(70)90126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grein F. Journal of Molecular Structure: THEOCHEM. 2001;536:87. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fleming I. Molecular Orbitals and Organic Chemical Reactions. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorenstein DG, Taira K. Biophys. J. 1984;46:749. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84073-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alabugin IV, Gilmore KM, Peterson PW. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Molecular Science. 2011;1:109. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edward JT. Chem. Ind. 1955;36:1102. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anet FAL, Yavari I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977;99:6752. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mo Y. Nat Chem. 2:666. doi: 10.1038/nchem.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorenstein DG, Findlay JB, Luxon BA, Kar D. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:3473. doi: 10.1021/ja00452a047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gorenstein DG, Luxon BA, Findlay JB. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1977;475:184. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(77)90353-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giesen DJ, Gu MZ, Cramer CJ, Truhlar DG. J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:8720. doi: 10.1021/jo9617427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirschner KN, Woods RJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191362798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kysel O, March P. Journal of Molecular Structure: THEOCHEM. 1991;227:285. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frushicheva MP, Cao J, Chu ZT, Warshel A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010381107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Florián J, Štrajbl M, Warshel A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:7959. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamane T, Okamura H, Ikeguchi M, Nishimura Y, Kidera A. Proteins. 2008;71:1970. doi: 10.1002/prot.21874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruben EA, Chapman MS, Evanseck JD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17789. doi: 10.1021/ja054708v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Y, Cui Q. J Phys Chem A. 2009;113:12439. doi: 10.1021/jp902949f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rudbeck ME, Nilsson Lill SO, Barth A. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:2751. doi: 10.1021/jp206414d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iche-Tarrat N, Barthelat JC, Vigroux A. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:3217. doi: 10.1021/jp710945w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petkso GA, Ringe D. Protein structure and function. London: New Science Press Ltd.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bottoms CA, White TA, Tanner JJ. Proteins. 2006;64:404. doi: 10.1002/prot.21014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Freer ST, Kraut J, Robertus JD, Wright HT, Xuong NH. Biochemistry. 1970;9:1997. doi: 10.1021/bi00811a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pedersen AK, Peters GG, Moller KB, Iversen LF, Kastrup JS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:1527. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904015094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phillips RS. Journal of Molecular Catalysis B: Enzymatic. 2002;19–21:103. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strajbl M, Shurki A, Warshel A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2436328100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shurki A, Strajbl M, Schutz CN, Warshel A. Methods Enzymol. 2004;380:52. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)80003-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheng H, Nikolic-Hughes I, Wang JH, Deng H, O'Brien PJ, Wu L, Zhang ZY, Herschlag D, Callender R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:11295. doi: 10.1021/ja026481z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones PG, Kirby AJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:6207. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones PG, Sheldrick GM, Kirby AJ, Abell KWY. Acta Crystallographica, Section C: Crystal Structure Communications. 1984;C40:547. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson, et al. Gaussian 09; Revision A.1 ed. Wallingford, CT: Gaussian, Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Physical Review B: Condensed Matter. 1988;37:785. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clark T, Chandrasekhar J, Spitznagel GW, Schleyer PVR. J. Comp. Chem. 1983;4:294. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Francl MM, Pietro WJ, Hehre WJ, Binkley JS, Gordon MS, Defrees DJ, Pople JA. J. Chem. Phys. 1982;77:3654. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Head-Gordon M, Pople JA, Frisch MJ. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1988;153:503. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miertus S, Scrocco E, Tomasi J. Chem. Phys. 1981;55:117. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kamerlin SC, Florian J, Warshel A. Chemphyschem. 2008;9:1767. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200800356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kamerlin SC, Haranczyk M, Warshel A. Chemphyschem. 2009;10:1125. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200800753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kelly CP, Cramer CJ, Truhlar DG. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2006;110:2493. doi: 10.1021/jp055336f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Glendening ED, Badenhoop JK, Reed AE, Carpenter JE, Bohmann JA, Morales CM, Weinhold F. NBO Version 5.9. 5.9 ed. Madison, Wisconsin: Theoretical Chemistry Institute, University of Wisconsin; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dunning T., Jr J. Chem. Phys. 1989;90:1007. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Foster JP, Weinhold F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:7211. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Glendening ED, Reed AE, Carpenter JE, Weinhold F. NBO 3.0 Program Manual. Theoretical Chemistry Institute and Department of Chemistry: University of Wisconsin-Madison; [Google Scholar]

- 64.Glendening ED, Reed AE, Carpenter JE, Weinhold F. NBO Version 3.1. (1 ed.) [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kamerlin SC, Warshel A. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:15692. doi: 10.1021/jp907223t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jeffrey GA, Saenger W. Hydrogen Bonding in Biological Structures. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kirby AJ. The Anomeric Effect and Related Stereoelectronic Effects at Oxygen. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kirby AJ. Stereoelectronic Effects. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ruben EA, Chapman MS, Evanseck JD. J Phys Chem A. 2007;111:10804. doi: 10.1021/jp0748112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Iancu CV, Borza T, Fromm HJ, Honzatko RB. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:26779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203730200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kack H, Gibson KJ, Lindqvist Y, Schneider G. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:5495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Larsen TM, Benning MM, Rayment I, Reed GH. Biochemistry. 1998;37:6247. doi: 10.1021/bi980243s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ramon-Maiques S, Marina A, Gil-Ortiz F, Fita I, Rubio V. Structure. 2002;10:329. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00721-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Davulcu O, Skalicky JJ, Chapman MS. Biochemistry. 2011;50:4011. doi: 10.1021/bi101664u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Johnston IA, Goldspink G. Nature. 1975;257:620. doi: 10.1038/257620a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Iwanami K, Iseno S, Uda K, Suzuki T. Gene. 2009;437:80. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hagelauer U, Faust U. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1982;20:633. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1982.20.9.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Travers F, Bertrand R, Roseau G, Van Thoai N. Eur J Biochem. 1978;88:523. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gilli P, Bertolasi V, Ferretti V, Gilli G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:909. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gilli G, Gilli P. The Nature of the Hydrogen Bond: Outline of a Comprehensive Hydrogen Bond Theory. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.