Abstract

Silver nanoparticles and silver-graphene oxide nanocomposites were fabricated using a rapid and green microwave irradiation synthesis method. Silver nanoparticles with narrow size distribution were formed under microwave irradiation for both samples. The silver nanoparticles were distributed randomly on the surface of graphene oxide. The Fourier transform infrared and thermogravimetry analysis results showed that the graphene oxide for the AgNP-graphene oxide (AgGO) sample was partially reduced during the in situ synthesis of silver nanoparticles. Both silver nanoparticles and AgGO nanocomposites exhibited stronger antibacterial properties against Gram-negative bacteria (Salmonella typhi and Escherichia coli) than against Gram-positive bacteria (Staphyloccocus aureus and Staphyloccocus epidermidis). The AgGO nanocomposites consisting of approximately 40 wt.% silver can achieve antibacterial performance comparable to that of neat silver nanoparticles.

Keywords: Antibacterial properties, Graphene oxide, Microwave irradiation, Nanocomposites, Silver nanoparticles

Background

Silver (Ag) is well known as an effective antibacterial material for treating wounds and chronic diseases [1]. It exhibits strong cytotoxicity against a broad range of microorganisms; however, the conventional usage of silver salt and silver metal, which may release the silver ion too rapidly or too inefficiently in silver releasing, has limited its biomedical applications [2]. Therefore, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) that possess high specific surface area and unique physicochemical properties have attracted abundance of interest in various fields [3]. Nowadays, AgNP has been widely used for coating of medical devices, wound dressing, water filtration, etc. [1,4].

It has been reported that chemical reduction is one of the most popular methods for the preparation of AgNP due to its simplicity, low cost, and ability to produce a large amount of sample [5]. In this process, a reducing agent is needed to initiate the formation of AgNP. Various types of green reducing agents have been studied for the synthesis of AgNP, such as chitosan [6] and sugars [7], plant extracts [8], and bacterium [9]. One of the simplest green synthesis methods was based on Tollens' process and uses glucose to form stable colloidal AgNP [10].

A microwave-assisted method had been reported for the synthesis of AgNP [11,12] since it is well known as a rapid process in producing metallic nanoparticles, for example, gold, platinum, and palladium [13]. The microwave chemistry involves a dipolar mechanism and ionic conduction [14,15]. Monodispersed nanoparticles with high crystallinity and small and uniform size distribution can be produced using microwave irradiation due to the homogeneous heating of the reaction medium, which improves the reaction rate to hasten the fast nucleation and crystal growth of nanoparticles [11,15]. In addition, microwave-assisted synthesis only requires lower energy consumption compared to conventional heating method [11,16].

Recent studies suggested that graphene oxide (GO) possesses antibacterial properties against Escherichia coli[17-19] and that AgNP-functionalized graphene-based materials exhibit enhanced antibacterial properties [20-23]. GO is a sheet of sp2-bonded single-carbon-atom-thick graphene which was chemically functionalized with oxygen functional groups such as carboxylic and carbonyl at the edges of the sheet, and epoxy and hydroxyl on the basal plane [24-27]. With the presence of the oxygen functional groups, exfoliated GO is well dispersed in polar solvents, such as water [28]. This hydrophilic property allows the deposition of metallic nanoparticles and, subsequently, the utilization in various applications [22,25,29-33].

In the present study, AgNP and AgNP-graphene oxide (AgGO) nanocomposites were prepared using the microwave approach as a rapid synthesis method by using glucose as a green reducing agent. The antibacterial properties of both samples against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria were investigated. The aim of this study is to produce a new nanocomposite material with lower silver content and comparable antibacterial performance.

Methods

Materials

The analytical-grade silver nitrate (AgNO3), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), ammonia, potassium permanganate (KMnO4, 99.9%), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30%), sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 98%), phosphoric acid (H3PO4, 85%), and glucose used in this study were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Graphite flakes were purchased from Asbury Graphite Mill, Inc. (Asbury, NJ, USA). GO was prepared using the simplified Hummer's method [34]. Briefly, graphite was oxidized to graphite oxide with H2SO4 and KMnO4, and H2O2 was added to stop the oxidation. Graphite oxide was washed with a simple decantation of the supernatant with repeated centrifugation until pH 7.0 was achieved, and followed by exfoliation in an ultrasonication bath.

Synthesis of AgNP and AgGO nanocomposites

AgNPs were synthesized using the modified Tollens' process. Briefly, silver oxide was formed by mixing AgNO3 (2 mM) and NaOH (2 mM). Then, the silver oxide was dissolved in ammonia solution (10 mM) to form silver ammonia complex. The reaction was followed by reduction using glucose (10 mM) in a commercial microwave oven (NN-SM330M, 700W, Panasonic, Osaka, Japan) for 60 s. After the reaction, the color of the solution turned into greenish-yellow, indicating the formation of AgNP. As to the synthesis of AgGO nanocomposite, silver ammonia complex was mixed with GO suspension (2.5 mg/ml) while stirring for 5 min and followed by the addition of glucose solution (1 mM). The mixture was then put into the microwave oven for 60 s. Both AgNP and AgGO nanocomposites were washed with deionized water by centrifugation to remove excess chemicals.

Characterizations

The UV-visible (UV-vis) spectrum and X-ray diffraction pattern of the AgNP and AgGO samples were obtained using a UV-vis spectrophotometer (Jenway 7315, Staffordshire, UK) and an X-ray diffractometer (Bruker Advance, Madison, WI, USA) to identify the formation of AgNP. The size and distribution of AgNP for both samples were examined using a scanning transmission electron microscopy (HD-2700 Cs-Corrected FE-STEM, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The silver content of the AgGO sample was estimated using energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) and induced coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (Optima 4300 DV, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

The chemical functional groups of GO and AgGO were characterized using attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infrared (Perkin Elmer Spectrum 400). The thermal properties of GO and AgGO were measured using a Pyris 1 thermogravimetry analyzer (TGA; Perkin Elmer). The AgGO sample was characterized using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (Axis Ultra DLD, Kratos/Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan).

Antibacterial test

The antibacterial activity of the AgNP and AgGO were tested on Gram-positive (Staphyloccocus aureus and Staphyloccocus epidermidis) and Gram-negative (E. coli and Salmonella typhi) bacteria. The bacteria (105 CFU) were inoculated in nutrient broth and incubated with AgNP and AgGO samples at five different concentrations (6.25 to 100 μg/ml) at a volume ratio of 1:1 for 4 h at 37°C. After the incubation, 0.1 ml of the mixture for each sample was spread on a nutrient agar plate, followed by incubation at 37°C for another 24 h. Control sample (sterilized distilled water) and 100 μg/ml GO were prepared and spread on an agar plate for standard comparison. All the agar plates were visually inspected for the presence of bacterial growth, and the results were recorded.

Results and discussion

Formation of AgNP and AgGO nanocomposites

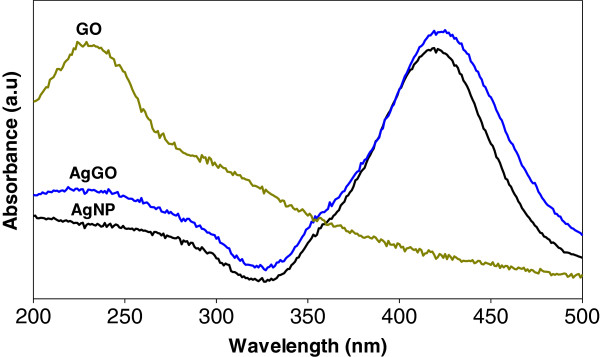

The UV-vis spectra of GO, AgNP, and AgGO are shown in Figure 1. The GO sample shows a strong absorption peak at 230 nm, which is due to the π → π* transitions of aromatic C-C bonds, while n → π* transitions of C=O bonds contribute to the shoulder at 300 nm [35]. Both AgNP and AgGO show a strong absorption peak at 418 and 420 nm, respectively, due to the surface plasmon resonance of AgNP. This phenomenon happened when the incident light interacted with the valence electrons at the outer band of AgNP, leading to the oscillation of electrons along with the frequency of the electromagnetic source [36]. There is a broad absorption range for the AgGO sample at 210 to 240 nm, which can be attributed to the presence of GO.

Figure 1.

UV-vis spectra of GO, AgNP, and AgGO.

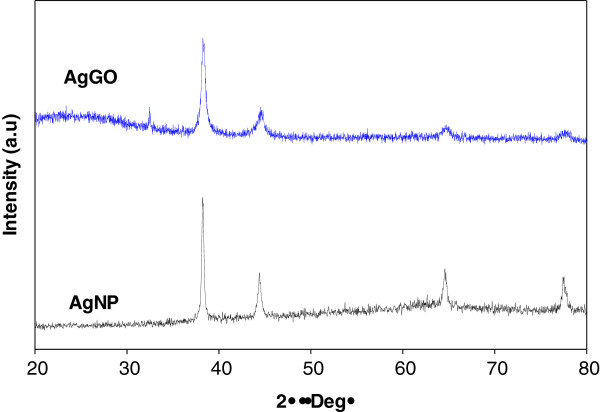

Figure 2 shows the X-ray diffraction spectra of the AgNP and AgGO samples. The formation of AgNP was confirmed by the existence of diffraction patterns of silver crystal structure, matching with the standard X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern (JCPDS no. 04-0783). The diffraction peaks for both samples at 38.1°, 44.3°, 64.5°, and 77.4° represent the crystallographic planes of (111), (200), (220), and (311) for the face-centered cubic of the silver crystal. These have further confirmed the formation of Ag crystals in both samples by using microwave irradiation method.

Figure 2.

XRD diffraction patterns for AgNP and AgGO.

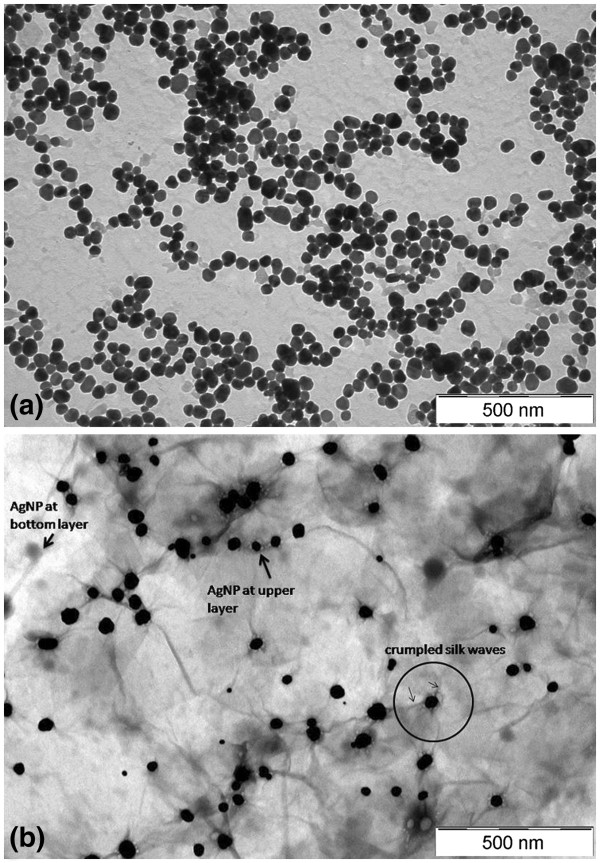

The electron microscopy images of the AgNP and AgGO nanocomposites are shown in Figure 3. Figure 3a reveals the spherical shape of AgNPs with an average size of 37.1 ± 5.1 nm. For the AgGO sample (Figure 3b), it can be seen that the AgNPs were deposited randomly on the GO sheets, and the AgNPs have an average size of 40.7 ± 7.5 nm. The presence of crumpled silk waves on the GO sheets can also be observed, which can be attributed to the deposition of AgNP on the surface of the GO sheets (circle area in Figure 3b). The deposition of AgNP on the upper and bottom layers of the translucent GO sheets can be differentiated by the black-and-white contrast of the particles.

Figure 3.

Electron microscopy images of the (a) AgNP and (b) AgGO.

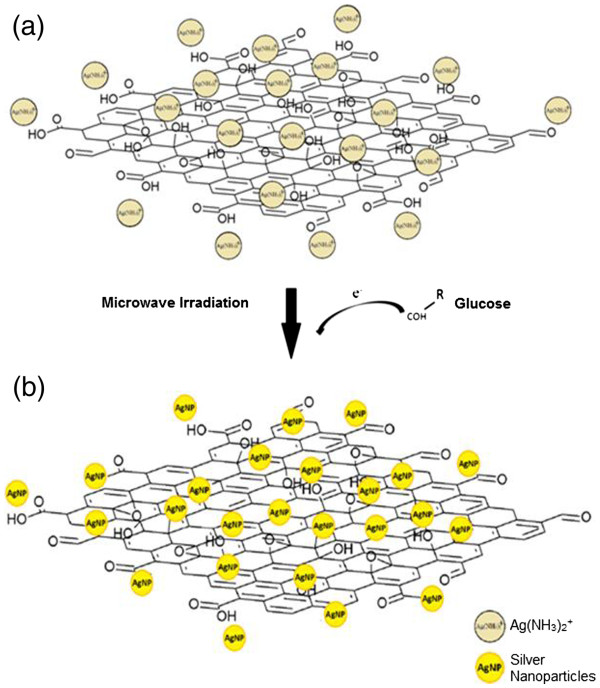

The mechanism of the AgGO formation is shown in Figure 4. Before the reduction by glucose, the positively charged silver ammonia complex, Ag(NH3)2+ can be easily attracted to the negatively charged oxygen functional group on GO (Figure 4a) [25]. After the addition of glucose into the mixture, the aldehyde groups of glucose will release electron to reduce silver ammonia complex. AgNP can then be easily deposited on the GO sheets once the complex is reduced due to the electrostatic attraction between the silver ammonia complex and GO sheets (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

The formation mechanism of AgGO nanocomposite using microwave irradiation. (a) The electrostatic interaction of Ag(NH3)2+ with oxygenated functional group on the GO sheets and (b) the addition of glucose to reduce AgNP under microwave irradiation.

Characterizations of AgGO

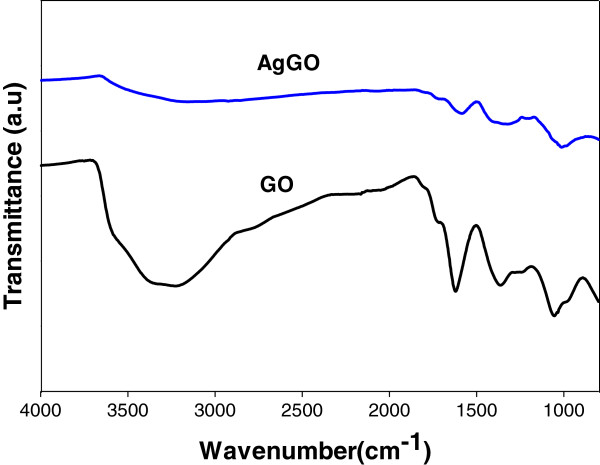

The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of GO and AgGO are shown in Figure 5. The presence of the adsorption band at approximately 1,619 cm−1 corresponds to the C=C bonding of the aromatic rings of the GO carbon skeleton structure. The presence of other oxygenated functional groups can also be detected, including OH at approximately 3,225 and 1,361 cm−1, C=O at approximately 1,714 cm−1, C-OH at approximately 1,209 cm−1, and C-O at approximately 1,054 cm−1. Meanwhile, there is a significant decrease in the intensity of the adsorption bands of the oxygenated functional groups for the AgGO sample (Figure 5). This can be due probably to the existence of AgNP on the surface of GO and also to the slight reduction of GO by glucose during the synthesis of the AgGO nanocomposite [37].

Figure 5.

FTIR spectra of GO and AgGO.

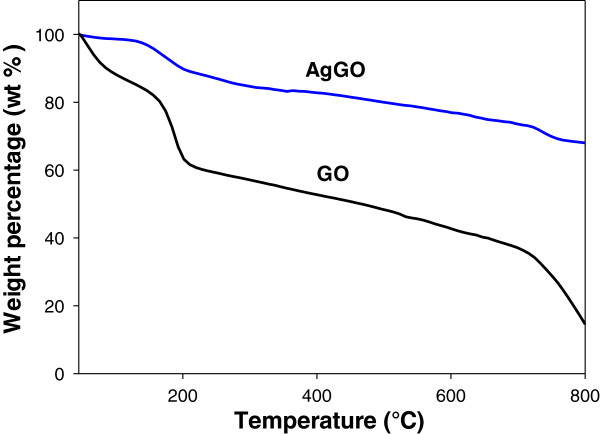

TGA was conducted for both GO and AgGO samples at temperatures ranging from 30°C to 800°C (Figure 6). The TG curve of the GO sample (Figure 6) shows a major weight loss (approximately 12 wt.%) below 100°C, which can be attributed to the removal of absorbed water [37]. As the temperature increased, the GO has lost approximately 22 wt.% due to the pyrolysis of oxygenated functional groups [38]. On the other hand, AgGO underwent similar weight loss within the same temperature range at a lower rate than that of the GO sample (Figure 6). This can be attributed to the reduction of thermally unstable oxygenated functional groups on the AgGO sample, which is consistent with the FTIR results. The greater thermal stability of the AgGO sample may also be due to the existence of AgNP.

Figure 6.

TGA of GO and AgGO.

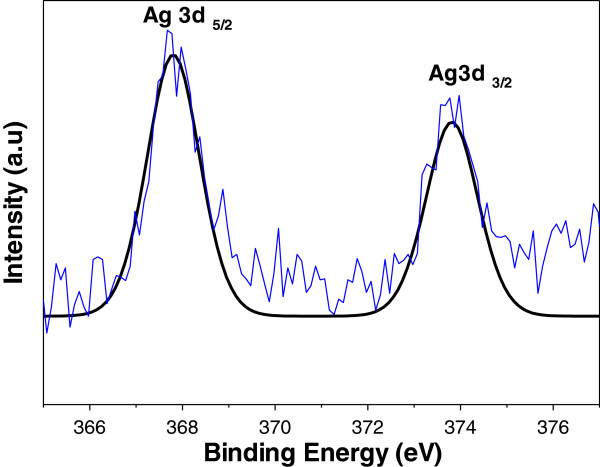

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was used to analyze the binding energy of Ag 3d in the AgGO sample. The intensity and curve fitting spectra are shown in Figure 7. The existence of two binding energies for Ag 3d for the AgGO sample, 367.8 and 373.8 eV, with a difference of 6.0 eV, proved the formation of metallic silver. The shift of both Ag 3d5/2 and Ag 3d3/2 (standard binding energies for pure silver are 368.1 and 374.1 eV) to the lower binding energy may be due to the occurrence of electron transfer between AgNP and GO. The results obtained from the TGA and FTIR suggested that the GO was partially reduced during the synthesis of AgGO. Therefore, the disrupted conductivity of GO might be restored during the reduction process by glucose and subsequently enhance the electron movement from Ag within the GO sheets [35].

Figure 7.

XPS elemental analysis of Ag 3 d in AgGO.

Antibacterial activity of AgNP and AgGO

Both AgNP and AgGO nanocomposites were tested for their antibacterial activity against bacteria at five different concentrations, i.e., 100, 50, 25, 12.5, and 6.25 μg/ml. Sterilized distilled water was used as a control sample (Additional file 1). After the incubation, all plates were observed for bacteria colony growth on the surface of the agar medium (Additional files 2, 3, 4, and 5). The observation was recorded and summarized in Table 1. As shown in Table 1, both the AgNP and AgGO samples generally exhibit antibacterial activity that is stronger against Gram-negative than against Gram-positive bacteria. AgGO effectively inhibits S. typhi growth at a relatively low concentration of 6.25 μg/ml; nevertheless, 69 colonies were still viable at 6.25 μg/ml in the case of AgNP. For E. coli, all tested concentrations of AgNP were inhibitory; however, the lower concentrations of 12.5 and 6.25 μg/ml yielded some surviving colonies, with less than five colonies counted. The results suggest that both AgNP and AgGO are effective anti-Gram-negative bacteria nanomaterials.

Table 1.

Inhibitory effect of AgNP and AgGO against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria

| Bacteria |

Sample concentrations (μg/ml) |

Control |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AgNP |

AgGO |

GO |

||||||||||

| 100 | 50 | 25 | 12.5 | 6.25 | 100 | 50 | 25 | 12.5 | 6.25 | 100 | - | |

| Gram-positive | ||||||||||||

| S. aureus |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

| S. epidermidis |

√ |

√ |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

× |

| Gram-negative | ||||||||||||

| E. coli |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√* |

√* |

× |

× |

| S. typhi | √ | √ | √ | √ | × | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | × | × |

A check indicates positive inhibition effect with no colony growth observed. A check with an asterisk indicates positive inhibition effect with less than five colonies observed. An ex indicates negative inhibition effect.

On the contrary, both AgNP and AgGO samples show contrasting effects on the Gram-positive bacteria S. aureus and S. epidermidis. Both AgNP and AgGO were not effective against S. aureus even at the highest tested concentration of 100 μg/ml. The growth of S. epidermidis was inhibited by AgNP at 100 and 50 μg/ml, but not at lower concentrations. However, AgGO failed to inhibit the bacteria even at the highest concentration tested.

The interesting result from Table 1 shows that neither Gram-positive nor Gram-negative bacteria exhibit any sign of decrease or inhibitory growth after incubation with a relatively high concentration of GO (100 μg/ml) (Additional file 1), unlike in previously reported works [17-19].

Antibacterial properties of Ag have been widely reported [7,39,40]. AgNPs are attached to the surface of bacteria's membrane and disturb its permeability and respiration ability during their interaction [7]. Furthermore, AgNP has a higher tendency to react with phosphorus and sulfur compounds in bacteria such as the membrane and DNA, causing the bacteria to lose its ability to replicate [39]. Additionally, Ag ions released from AgNP could penetrate into bacteria and cause damage on bacterial main components such as the peptidoglycan, DNA, and protein. These would then lead to the malfunction of the bacterial replication system [41].

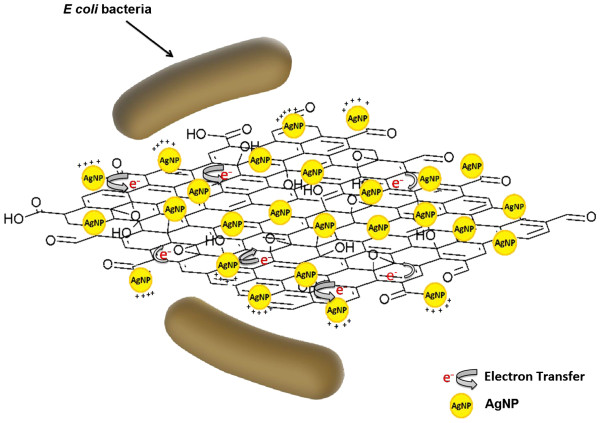

The Ag content of AgGO obtained by ICP-OES is 39.5%, which is close to the EDS result (42.5%). This means that a comparable antibacterial performance could be achieved using AgGO with a lower concentration of Ag, as compared to the lone AgNP. AgGO is postulated to have a similar mechanism with that of AgNP with the additional effect from GO. The synergistic effect of AgGO may begin with the wrapping mechanism by the flexible GO sheets, which provides a large surface area substrate for the deposition of AgNP. According to previous studies, GO could adhere to or wrap on the E. coli through hydrogen bonds between the bacteria's lipopolysaccharides and the oxygenated functional groups of GO [21,23]. Hence, GO could prevent the nutrient-uptaking process of the bacteria from the surrounding while increasing the interaction between AgNP and the bacteria [21]. The close interaction inflicts a chain reaction starting with the damage and disruption of the bacterial membrane by AgNP, followed by the chemical interaction between the AgNP and the sulfur- and phosphorous-containing compounds of the bacteria [7,39]. Besides, Ag ions can be released more easily into the bacteria, causing mutilation on the respiration and replication of bacteria, and eventually leading to bacterial cell death [42].

The ATR-FTIR results suggest that the GO sheets of the AgGO sample were partially reduced by glucose during the formation and deposition of AgNP on GO. This reduction caused the restoration of the electroconductivity of GO due to the removal of oxygenated functional groups. Moreover, the XPS result of the AgGO [35] indicates the shifting of Ag 3d towards the lower binding energy due to the interaction and electron transfer between the metallic Ag and carboxyl groups of the GO sheets. GO with restored electroconductivity could increase the electron transfer rate from the AgNP to the GO, leading to the formation of partially positively charged AgNP, which can enhance the inhibition effect on the cell growth of bacteria. The plausible mechanism above is presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Plausible antibacterial mechanism of AgGO against E. coli.

The difference in the antibacterial activities of both samples may be due to the structural difference between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, whereby the former bacteria have a thicker peptidoglycan layer at the outer cell [2]. This is also in agreement with a previous study which reported that AgNP possesses antibacterial effect that is stronger against E. coli than S. aureus due to the thinner peptidoglycan layer of Gram-negative bacteria [40]. Therefore, the thicker peptidoglycan layer of Gram-positive bacteria might provide protection against the attack by AgNP.

Conclusions

Microwave irradiation provides a rapid and green method for the synthesis of AgNP and AgGO. It favors the formation of small and uniform nanoparticles through a fast and homogeneous nucleation and crystallization. Both AgNP and AgGO nanocomposites showed antibacterial activity that is stronger against Gram-negative bacteria (E. coli and S. typhi) than against Gram-positive bacteria, (S. aureus and S. epidermidis). Meanwhile, the results showed that GO did not exhibit antibacterial activity. The synergistic effect between GO and AgNP has reduced the Ag content without compromising the antibacterial performance. The advantage of this nanocomposite with low Ag content will reduce the concern and risk of excessive Ag usage, which make it a potential material for food packaging and wound dressing applications.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SWC, CHC, HMN, and KLC conceived and designed all the experiments. SWC performed all the experiments. RMFRAR helped SWC in performing the antibacterial experiments. RJ and HMN helped SWC in interpreting the antibacterial tests of the samples. SZ, MKA, NMH, and HNL participated in the discussion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Digital images for antibacterial effect of water control and GO.

Table S2. Digital images for antibacterial effect of AgNP and AgGO against Staphyloccocus aureus.

Table S3. Digital images for antibacterial effect of AgNP and AgGO against Staphyloccocus epidermidis.

Table S4. Digital images for antibacterial effect of AgNP and AgGO against Escherichia coli.

Table S4. Digital images for antibacterial effect of AgNP and AgGO against Salmonella typhi.

Contributor Information

Soon Wei Chook, Email: chooksoonwei@gmail.com.

Chin Hua Chia, Email: chiachinhua@yahoo.com.

Sarani Zakaria, Email: sarani@ukm.my.

Mohd Khan Ayob, Email: mkhan@ukm.my.

Kah Leong Chee, Email: cklcat1437@gmail.com.

Nay Ming Huang, Email: huangnayming@gmail.com.

Hui Min Neoh, Email: meridianv22@hotmail.com.

Hong Ngee Lim, Email: janet_limhn@yahoo.com.

Rahman Jamal, Email: rahmanj@ppukm.ukm.my.

RahaMohdFadhilRajaAbdul Rahman, Email: ashran_zara@yahoo.com.my.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the financial support via the research project grants UKM-GGPM-NBT-085-2010, DIP-2012-34, and UM.C/625/1/HIR/030.

References

- Rai M, Yadav A, Gade A. Silver nanoparticles as a new generation of antimicrobials. Biotechnol Adv. 2009;27:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS, Kuk E, Yu KN, Kim J-H, Park SJ, Lee HJ, Kim SH, Park YK, Park YH, Hwang C-Y, Kim YK, Lee YS, Jeong DH, Cho MH. Antimicrobial effects of silver nanoparticles. Nanomed Nanotechnol Biol Med. 2007;3:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soukupová J, Kvítek L, Panáček A, Nevěčná T, Zbořil R. Comprehensive study on surfactant role on silver nanoparticles (NPs) prepared via modified Tollens process. Mater Chem Phys. 2008;111:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2008.03.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krutyakov YA, Kudrinskiy AA, Olenin AY, Lisichkin GV. Synthesis and properties of silver nanoparticles: advances and prospects. Russ Chem Rev. 2008;77:233. doi: 10.1070/RC2008v077n03ABEH003751. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song K, Lee S, Park T, Lee B. Preparation of colloidal silver nanoparticles by chemical reduction method. Korean J Chem Eng. 2009;26:153–155. doi: 10.1007/s11814-009-0024-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang NM, Radiman S, Lim HN, Khiew PS, Chiu WS, Lee KH, Syahida A, Hashim R, Chia CH. γ-Ray assisted synthesis of silver nanoparticles in chitosan solution and the antibacterial properties. Chem Eng J. 2009;155:499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2009.07.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panáček A, Kvítek L, Prucek R, Kolář M, Večeřová R, Pizúrová N, Sharma VK, Nevŕčná TJ, Zboril R. Silver colloid nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization, and their antibacterial activity. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:16248–16253. doi: 10.1021/jp063826h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raut RW, Kolekar NS, Lakkakula JR, Mendhulkar VD, Kashid SB. Extracellular synthesis of silver nanoparticles using dried leaves of Pongamia pinnata (L) pierre. Nano-Micro Lett. 2010;2:106–113. [Google Scholar]

- Namasivayam SKR, GKK E, RR. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles by Lactobaciluus acidophilus 01 strain and evaluation of its in vitro genomic DNA toxicity. Nano-Micro Lett. 2010;2:160. [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Li Z-Y, Zhong Z, Gates B, Xia Y, Venkateswaran S. Synthesis and characterization of stable aqueous dispersions of silver nanoparticles through the Tollens process. J Mater Chem. 2002;12:522–527. doi: 10.1039/b107469e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Wang S-B, Wang K, Zhang M, Yu S-H. Microwave-assisted rapid facile “green” synthesis of uniform silver nanoparticles: self-assembly into multilayered films and their optical properties. J Phys Chem C. 2008;112:11169–11174. doi: 10.1021/jp801267j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masurkar SA, Chaudhari PR, Shidore VB, Kamble SP. Rapid biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Cymbopogan citratus (lemongrass) and its antimicrobial activity. Nano-Micro Lett. 2011;3:189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Mallikarjuna NN, Varma RS. Microwave-assisted shape-controlled bulk synthesis of noble nanocrystals and their catalytic properties. Cryst Growth Des. 2007;7:686–690. doi: 10.1021/cg060506e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bilecka I, Niederberger M. Microwave chemistry for inorganic nanomaterials synthesis. Nanoscale. 2010;2:1358–1374. doi: 10.1039/b9nr00377k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji M, Hashimoto M, Nishizawa Y, Kubokawa M, Tsuji T. Microwave-assisted synthesis of metallic nanostructures in solution. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:440–452. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadagouda MN, Speth TF, Varma RS. Microwave-assisted green synthesis of silver nanostructures. Accounts of Chemical Research. 2011;44:469–478. doi: 10.1021/ar1001457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhavan O, Ghaderi E. Toxicity of graphene and graphene oxide nanowalls against bacteria. ACS Nano. 2010;4:5731–5736. doi: 10.1021/nn101390x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Peng C, Luo W, Lv M, Li X, Li D, Huang Q, Fan C. Graphene-based antibacterial paper. ACS Nano. 2010;4:4317–4323. doi: 10.1021/nn101097v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Zeng TH, Hofmann M, Burcombe E, Wei J, Jiang R, Kong J, Chen Y. Antibacterial activity of graphite, graphite oxide, graphene oxide, and reduced graphene oxide: membrane and oxidative stress. ACS Nano. 2011;5:6971–6980. doi: 10.1021/nn202451x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W-P, Zhang L-C, Li J-P, Lu Y, Li H-H, Ma Y-N, Wang W-D, Yu S-H. Facile synthesis of silver@graphene oxide nanocomposites and their enhanced antibacterial properties. J Mater Chem. 2011;21:4593–4597. doi: 10.1039/c0jm03376f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Zhang J, Xiong Z, Yong Y, Zhao XS. Preparation, characterization and antibacterial properties of silver-modified graphene oxide. J Mater Chem. 2011;21:3350–3352. doi: 10.1039/c0jm02806a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Das MR, Sarma RK, Saikia R, Kale VS, Shelke MV, Sengupta P. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles in an aqueous suspension of graphene oxide sheets and its antimicrobial activity. Colloids Surfs B. 2011;83:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Liu J, Wang Y, Yan X, Sun DD. Facile synthesis of monodispersed silver nanoparticles on graphene oxide sheets with enhanced antibacterial activity. New J Chem. 2011;35:1418–1423. doi: 10.1039/c1nj20076c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geim AK, Novoselov KS. The rise of graphene. Nat Mater. 2007;6:183–191. doi: 10.1038/nmat1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Wang X. Fabrication of flexible metal-nanoparticle films using graphene oxide sheets as substrates. Small. 2009;5:2212–2217. doi: 10.1002/smll.200900548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Murali S, Cai W, Li X, Suk JW, Potts JR, Ruoff RS. Graphene and graphene oxide: synthesis, properties, and applications. Adv Mater. 2010;22:3906–3924. doi: 10.1002/adma.201001068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer DR, Park S, Bielawski CW, Ruoff RS. The chemistry of graphene oxide. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:228–240. doi: 10.1039/b917103g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes JI, Villar-Rodil S, Martínez-Alonso A, Tascón JMD. Graphene oxide dispersions in organic solvents. Langmuir. 2008;24:10560–10564. doi: 10.1021/la801744a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Phan T-D, Pham VH, Shin EW, Pham H-D, Kim S, Chung JS, Kim EJ, Hur SH. The role of graphene oxide content on the adsorption-enhanced photocatalysis of titanium dioxide/graphene oxide composites. Chem Eng J. 2011;170:226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2011.03.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y-K, He C-E, He W-J, Yu L-J, Peng R-G, Xie X-L, Wang X-B, Mai Y-W. Reduction of silver nanoparticles onto graphene oxide nanosheets with N, N-dimethylformamide and SERS activities of GO/Ag composites. J Nanopart Res. 2011;13:5571–5581. doi: 10.1007/s11051-011-0550-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves G, Marques PAAP, Granadeiro CM, Nogueira HIS, Singh MK, Grácio J. Surface modification of graphene nanosheets with gold nanoparticles: the role of oxygen moieties at graphene surface on gold nucleation and growth. Chem Mater. 2009;21:4796–4802. doi: 10.1021/cm901052s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liao C-S, Liao C-T, Tso C-Y, Shy H-J. Microwave-polyol synthesis and electrocatalytic performance of Pt/graphene nanocomposites. Mater Chem Phys. 2011;130:270–274. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2011.06.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Tian J, Wang L, Sun X. Microwave-assisted rapid synthesis of Ag nanoparticles/graphene nanosheet composites and their application for hydrogen peroxide detection. J Nanopart Res. 2011;13:4539–4548. doi: 10.1007/s11051-011-0410-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HN, Huang NM, Lim SS, Harrison I, Chia CH. Fabrication and characterization of graphene hydrogel via hydrothermal approach as a scaffold for preliminary study of cell growth. Int J Nanomed. 2011;6:1817–1823. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S23392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Liu C-y. Ag/graphene heterostructures: synthesis, characterization and optical properties. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2010;2010:1244–1248. doi: 10.1002/ejic.200901048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evanoff DD, Chumanov G. Synthesis and optical properties of silver nanoparticles and arrays. Chemphyschem. 2005;6:1221–1231. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200500113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C, Guo S, Fang Y, Dong S. Reducing sugar: new functional molecules for the green synthesis of graphene nanosheets. ACS Nano. 2010;4:2429–2437. doi: 10.1021/nn1002387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Shi M, Li N, Yan B, Ma H, Hu Y, Ye M. Facile synthesis and application of Ag-chemically converted graphene nanocomposite. Nano Res. 2010;3:339–349. doi: 10.1007/s12274-010-1037-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morones JR, Elechiguerra JL, Camacho A, Holt K, Kouri JB, Ramírez JT, Yacaman MJ. The bactericidal effect of silver nanoparticles. Nanotechnol. 2005;16:2346. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/16/10/059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le A-T, Tam LT, Tam PD, Huy PT, Huy TQ, Van Hieu N, Kudrinskiy AA, Krutyakov YA. Synthesis of oleic acid-stabilized silver nanoparticles and analysis of their antibacterial activity. Mater Sci Eng C. 2010;30:910–916. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2010.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaloupka K, Malam Y, Seifalian AM. Nanosilver as a new generation of nanoproduct in biomedical applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2010;28:580–588. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le A-T, Huy PT, Tam PD, Huy TQ, Cam PD, Kudrinskiy AA, Krutyakov YA. Green synthesis of finely-dispersed highly bactericidal silver nanoparticles via modified Tollens technique. Curr Appl Phs. 2010;10:910–916. doi: 10.1016/j.cap.2009.10.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Digital images for antibacterial effect of water control and GO.

Table S2. Digital images for antibacterial effect of AgNP and AgGO against Staphyloccocus aureus.

Table S3. Digital images for antibacterial effect of AgNP and AgGO against Staphyloccocus epidermidis.

Table S4. Digital images for antibacterial effect of AgNP and AgGO against Escherichia coli.

Table S4. Digital images for antibacterial effect of AgNP and AgGO against Salmonella typhi.