Abstract

Flaveria bidentis (L.) Kuntze, a C4 dicot, was genetically transformed with a construct encoding the mature form of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) carbonic anhydrase (CA) under the control of a strong constitutive promoter. Expression of the tobacco CA was detected in transformant whole-leaf and bundle-sheath cell (bsc) extracts by immunoblot analysis. Whole-leaf extracts from two CA-transformed lines demonstrated 10% to 50% more CA activity on a ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase-site basis than the extracts from transformed, nonexpressing control plants, whereas 3 to 5 times more activity was measured in CA transformant bsc extracts. This increased CA activity resulted in plants with moderately reduced rates of CO2 assimilation (A) and an appreciable increase in C isotope discrimination compared with the controls. With increasing O2 concentrations up to 40% (v/v), a greater inhibition of A was found for transformants than for wild-type plants; however, the quantum yield of photosystem II did not differ appreciably between these two groups over the O2 levels tested. The quantum yield of photosystem II-to-A ratio suggested that at higher O2 concentrations, the transformants had increased rates of photorespiration. Thus, the expression of active tobacco CA in the cytosol of F. bidentis bsc and mesophyll cells perturbed the C4 CO2-concentrating mechanism by increasing the permeability of the bsc to inorganic C and, thereby, decreasing the availability of CO2 for photosynthetic assimilation by ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase.

The C4 photosynthetic pathway functions as a CO2-concentrating mechanism by raising the concentration of CO2 around Rubisco. As a result, the carboxylase activity of the enzyme operates near its Vmax, and the oxygenase activity and photorespiration are suppressed. An important aspect of the C4 pathway is that the reactions of photosynthesis are divided between the mesophyll and the bsc; Rubisco and the C3 photosynthetic C reduction cycle are located exclusively in the chloroplasts of the bundle sheath, whereas the initial assimilation of atmospheric CO2 takes place in the mesophyll cell cytosol (Hatch, 1987). This partitioning of the photosynthetic reactions between distinct cell types results in a CO2-concentrating mechanism whereby CO2 is pumped into the bundle sheath, reaching levels up to 20 times higher than those of the surrounding mesophyll cells (Jenkins et al., 1989).

The enzyme CA (EC 4.2.1.1) catalyzes the reversible interconversion of CO2 and HCO3− and, in higher plants, may represent up to 2% of the soluble-leaf protein (Okabe et al., 1984). Multiple forms of CA have been reported from leaf tissue of both C3 and C4 plants (Atkins et al., 1972; Reed and Graham, 1981; Fett and Coleman, 1994; Ludwig and Burnell, 1995; Rumeau et al., 1996; Burnell and Ludwig, 1997). In plants demonstrating C3 photosynthesis, most of the CA activity is localized to the stroma of the mesophyll chloroplasts (Poincelot, 1972; Jacobson et al., 1975; Tsuzuki et al., 1985), where it is believed to facilitate the diffusion of CO2 across the chloroplast envelope (Reed and Graham, 1981; Cowan, 1986; Price et al., 1994). In C4 plants, however, most of the CA activity is found in the mesophyll cell cytosol (Gutierrez et al., 1974; Ku and Edwards, 1975; Burnell and Hatch, 1988), where it catalyzes the hydration of atmospheric CO2 to HCO3−, which is the substrate for the primary carboxylating enzyme of the C4 pathway, PEP carboxylase (Hatch and Burnell, 1990).

Biochemical and modeling studies (Furbank and Hatch, 1987; Burnell and Hatch, 1988) have previously maintained that the absence of CA in the bundle sheath of C4 plants is essential for an effective CO2-concentrating mechanism and, thereby, efficient functioning of the C4 pathway. However, when Jenkins et al. (1989) considered the presence of CA in the bundle-sheath cytosol in their model, they predicted that even a 1000-fold increase in CA activity over the noncatalyzed rate would have only a moderate effect on the efficiency of C4 photosynthesis.

The recent development of a transformation system for the NADP-ME-type C4 dicot Flaveria bidentis (L.) Kuntze (Chitty et al., 1994) offers the opportunity to genetically manipulate various aspects of the C4 photosynthetic pathway (Furbank et al., 1997). To directly determine the effects of elevated CA activity in the cytosol of C4 bsc and mesophyll cells, we have transformed wild-type F. bidentis plants with a construct encoding tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) CA without the putative chloroplast transit peptide. Because this sequence encoding the mature form of the tobacco enzyme was under the control of the constitutive CaMV 35S promoter, expression of the tobacco CA was expected in the cytosol of both the mesophyll and bsc of the transformants. The expression of this introduced CA in F. bidentis and its activity, as well as the effects of this expression on the efficiency of C4 photosynthesis, are described.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression of Tobacco CA in Escherichia coli and Generation of Antiserum

A cDNA clone encoding tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) CA (Price et al., 1994) was adapted for expression in E. coli through the use of the following PCR oligonucleotides: 5′-AGAGTTGACGGATCCATGGCTGAATTGCAATC and 5′-CACTTAAAACGGAATTCGAGCTCATACGGAA. The first primer allowed the removal of the transit peptide-coding region of tobacco CA and introduced a BamHI site followed by an NcoI site near the putative start of the mature peptide, which was assumed to be Gln-101 (Majeau and Coleman, 1992) by analogy to spinach CA (Burnell et al., 1990). These modifications resulted in a start sequence of MAELQ for the recombinant gene product. The second primer introduced SacI and EcoRI sites immediately downstream of the tobacco CA cDNA stop codon. The resulting 660-bp PCR product was digested with BamHI and EcoRI and cloned into the corresponding sites of the E. coli expression vector pTrcHisA (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The resulting construct, named ptrcTOBCA, was further modified by the deletion of a 104-bp NcoI/NcoI fragment, thus removing the polyHis leader from pTrcHisA. This second construct was named ptrcTOBCA-Nco/Nco. Both constructs expressed the recombinant CA at high levels (up to 20% of soluble protein) in E. coli JM109 cells, and the protein was fully active in the presence of DTT and had properties identical to CA from tobacco leaf extracts (G.D. Price, unpublished data). Protein expressed from ptrcTOBCA-Nco/Nco was purified by SDS-PAGE and used for the generation of rabbit polyclonal antibodies essentially as described by Price et al. (1995). To reduce nonspecific binding, antiserum was preabsorbed to an acetone powder of E. coli JM109 cells (Harlow and Lane, 1988).

Construction of pBI-CA-GUS Binary Plasmid

The region encoding mature tobacco CA was removed from ptrcTOBCA as a 660-bp BamHI/SacI fragment and ligated into the corresponding sites of the pBI-GUS-B6F binary plasmid, as detailed by Price et al. (1995). The NcoI site behind the BamHI site of the CA clone was selected to produce a context that could act as a Kozak ribosome-binding site (Kozak, 1983).

Plant Transformation and Regeneration

Flaveria bidentis (L.) Kuntze plants were transformed and regenerated using the pBI-CA-GUS construct and the Agrobacterium tumefaciens method described by Chitty et al. (1994). Selection of transformants was made on kanamycin-containing medium. Measurements of neomycin phosphotransferase II and GUS activity were made on the primary transformants following the procedures of Chitty et al. (1994). Primary transformants were allowed to self-fertilize and T1 seeds were collected. The T1 seeds from six different primary transformants, 190–1, 190–3, 191–2, 191–4, 191–7, and 191–8, were sown and plants were grown in a naturally lit greenhouse (von Caemmerer et al., 1997b).

Detection of Tobacco CA in T1 and T2 F. bidentis Plants

Leaf discs measuring 0.5 cm2 were collected from the youngest, fully expanded leaves of both tobacco plants and the progeny of the six F. bidentis primary transformed lines. Leaf discs were snap frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C until use. Total leaf protein was extracted from a leaf disc in 500 μL of 50 mm Hepes-KOH, pH 7.2, containing 1% (w/v) insoluble PVP, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm DTT, 5 mm MgCl2, and 1 mm PMSF in a 2-mL ground-glass tissue homogenizer on ice. An equal volume of 2× Tricine SDS-PAGE sample buffer (1× buffer is 450 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.45, 12% [v/v] glycerol, 4% [w/v] SDS, 0.0075% [w/v] Coomassie blue G, 0.0025% [w/v] phenol red, and 100 mm DTT) was added to the leaf extracts, which were then boiled for 4 min and centrifuged to clarify. Equivalent amounts of the extracts, based on equal leaf area of starting material, were separated on Tricine 10 to 20% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels (Novex gels, AMRAD Biotech, Boronia, Victoria, Australia) and then blotted to nitrocellulose (Schleicher & Schuell) using a semidry blotting apparatus (NovaBlot Unit, AMRAD Biotech) with a continuous buffer system (39 mm Gly, 48 mm Tris, 0.0375% [w/v] SDS, and 20% [v/v] methanol).

Gels were blotted at room temperature for 1.5 h at 0.54 mA cm−2. Nonspecific binding sites on the membranes were blocked by an overnight incubation in 12.5 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing 137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, and 1% (v/v) Tween 20 (TBST) with 5% (w/v) skim-milk powder. Blots were then incubated in a 1:1000 dilution of the anti-tobacco CA antiserum in the blocking buffer at room temperature for 2 h. Blots were washed three times in TBST and then labeled with a 1:3000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase conjugated-donkey anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Amersham) in the above blocking buffer. After several washes in TBST and a final wash in TBST without detergent, immunoreactive polypeptides were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence western-blotting analysis system (Amersham).

Gas-Exchange and C Isotope Measurements

Gas-exchange measurements were made together with measurements of C isotope discrimination, Δ, on attached, youngest, fully expanded leaves using an open gas-exchange system described by von Caemmerer and Evans (1991). C isotope discrimination was measured by collecting the CO2 in the air stream leaving the leaf chamber with and without a leaf present, and then calculating the difference in C isotope composition (von Caemmerer and Evans, 1991; von Caemmerer et al., 1997b). Measurements were made at 2000 μmol quanta m−2 s−1, a leaf temperature of 25°C, and an ambient CO2 concentration of 350 μbar. Leaf discs (0.5 cm2) taken from the same leaves after gas-exchange measurements were plunged into liquid N2 and stored at −80°C for subsequent biochemical assays. C isotope discrimination of leaf dry matter was determined on the leaf opposite that used in gas exchange as described by von Caemmerer et al. (1997b).

Gas-Exchange and Chl Fluorescence Measurements

Gas-exchange and Chl fluorescence measurements were made as described by Siebke et al. (1997) with a pulse-modulated fluorometer (PAM 101, Walz, Effeltrich, Germany) attached to a portable photosynthesis system (model 6400, Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE), which was fitted with a special cuvette that held a polyfurcated fiber optic connecting the different light sources and the measuring beam. Gases were supplied from pressurized gas cylinders containing N2 and O2 and mixed with electrical mass-flow controllers (type 1179A, MKS Instruments, Andover, MA) to obtain the desired concentrations. The CO2 concentration was adjusted with the Li-Cor 6400 CO2 injection system. The O2 concentration of the analyzed gas is known to influence the estimation of the water-vapor concentration by the injection system, and the calibration at different O2 concentrations was adjusted accordingly (S. von Caemmerer, unpublished data). The ΦPSII was calculated according to the method of Genty et al. (1989).

Biochemical Measurements

Leaf discs collected at the time of gas-exchange measurements were homogenized in 500 μL of extraction buffer as described above and centrifuged to clarify. Aliquots of the extracts were used to quantify soluble protein (Coomassie Plus reagent, Pierce) and Rubisco content was determined by the [14C]2′-carboxy-d-arabinitol-1,5-bisphosphate-binding assay (Butz and Sharkey, 1989; Mate et al., 1993). CA activity was determined using a MS technique that measured the rate of 18O exchange from doubly labeled 13C18O2 to H216O (Badger and Price, 1989). These assays were performed with 1 mm inorganic C at 25°C with the other modifications noted by Price et al. (1994). Total Chl content was determined according to the method of Porra et al. (1989).

Isolation of Bundle-Sheath Strands

Upper, fully expanded leaves were collected, deribbed, and sliced into 2- to 4-mm-wide strips. Approximately 0.6 g of leaf strips was homogenized in 1 mL of extraction buffer as described above (equals whole-leaf samples), whereas the remaining strips were used to prepare bundle-sheath strands according to the method of Meister et al. (1996). Proteins were extracted from bsc by homogenizing a concentrated aliquot of bundle-sheath strands in 1 mL of extraction buffer. Aliquots of whole-leaf and bsc extracts, clarified by centrifugation, were used to determine CA activity, Rubisco content, and soluble-protein concentration as described above. Separation of extracts by Tricine SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis were carried out as described above, except that samples were loaded onto the gel based on equivalent amounts of Rubisco protein.

At the time of bundle-sheath strand isolation, an upper, fully expanded leaf and bundle-sheath strands from each plant were frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C. These samples were subsequently used to determine the extent of mesophyll contamination of the bundle-sheath strand preparations using PEP carboxylase and phosphoribulokinase as mesophyll and bsc marker enzymes, respectively (Lunn and Furbank, 1997).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Expression of Active Tobacco CA in Transgenic F. bidentis

A number of A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation events using the mature tobacco CA construct (Fig. 1) gave rise to kanamycin-resistant F. bidentis plants, which tested positive in both GUS and neomycin phosphotransferase II assays (data not shown). Under the regeneration and growth conditions used, however, no obvious visual phenotype was detected in the transformants. No further data were collected from the primary transformants and they were allowed to self-fertilize and set seed. The T1 seeds from six different primary transformants were sown and, again, the resulting plants showed no differences in phenotype when compared with wild-type F. bidentis plants. To determine if the T1 progeny were expressing the mature tobacco CA polypeptide, a large number of these plants were screened using immunoblot analysis.

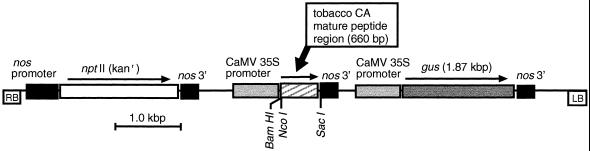

Figure 1.

Map of the binary construct, pBI-CA-GUS, used in the transformation of F. bidentis. The 660-bp BamHI/SacI fragment encoding the mature tobacco CA polypeptide and the gus gene were flanked by the CaMV 35S promoter and the 3′ end of the nopaline synthase (nos) gene. The nptII gene was flanked by the promoter and the 3′ end of the nos gene. Direction of transcription of the genes is indicated by the arrows. kanr, Kanamycin resistance; RB and LB, right and left borders of the T-DNA, respectively.

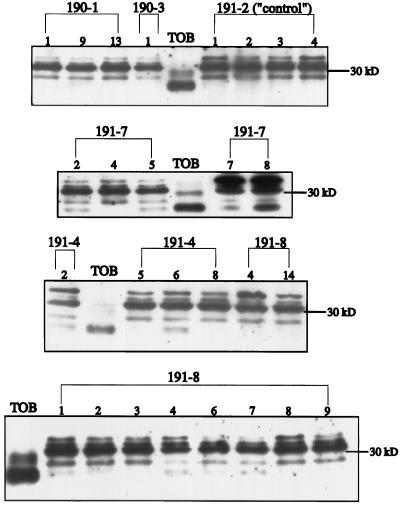

The antiserum raised against the recombinant tobacco CA labeled the mature form of the CA polypeptide (24 kD; Majeau and Coleman, 1992) in tobacco leaf extracts (Fig. 2, lanes TOB). The upper, less intensely labeled immunoreactive polypeptides detected in the tobacco leaf extracts are probably either processing intermediate forms of the enzyme or perhaps other isoforms of tobacco CA, as has been suggested for pea CA (Majeau and Coleman, 1991; Johansson and Forsman, 1992; Provart et al., 1993). The anti-tobacco CA antiserum labeled four polypeptides in control F. bidentis leaf extracts with molecular masses of approximately 35, 32, 30, and 27.5 kD (Fig. 2, line 191–2). Previously, two distinct CA polypeptides were identified in F. bidentis leaf extracts using an anti-spinach CA antiserum (Ludwig and Burnell, 1995). The discrepancy between these CA-labeling patterns is likely due to differing specificities and titers of the two antisera. Results from N-terminal amino acid sequencing indicate that the four F. bidentis polypeptides labeled with the anti-tobacco CA antiserum represent different isoforms of CA (M. Ludwig, unpublished data). Accumulating molecular evidence also indicates that CA is encoded by a multigene family in higher plants (Fett and Coleman, 1994; Ludwig and Burnell, 1995; Rumeau et al., 1996; Burnell and Ludwig, 1997).

Figure 2.

Detection of tobacco CA expression in T1 leaf extracts using immunoblot analysis. Numbers above the brackets designate F. bidentis primary transformed lines, whereas the numbers directly above the gel lanes represent individual progeny from the primary transformants. Equivalent amounts of tobacco (TOB) and F. bidentis leaf extracts based on equal leaf-area starting material were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted to nitrocellulose, and labeled with the anti-tobacco CA antiserum. Immunoreactive polypeptides were detected with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and the enhanced chemiluminescence labeling method as described in Methods. The position of the 30-kD molecular mass marker is indicated.

Figure 2 also shows some of the results obtained from screening T1 individuals for the expression of tobacco CA. Clearly, the tobacco CA polypeptide was detected in a number of progeny from several of the primary transformed lines (Fig. 2, lines 191–7, 191–4, and 191–8). However, the labeling intensity of the tobacco CA polypeptide always appeared much less than the total immunoreactive signal from the F. bidentis CA polypeptides in these transformants. Furthermore, the level of tobacco CA expression varied among the lines and even among the progeny from a given primary transformant (Fig. 2, 191–7.5 versus 191–7.8).

To determine if the tobacco CA, which was modestly expressed in the F. bidentis transformants, was biochemically active in these plants, a sensitive MS assay, which measured the rate of exchange of 18O from doubly labeled 13C18O2 to H216O (Badger and Price, 1989; Price et al., 1994), was used. Individuals from line 191–7, a transformed line producing progeny expressing relatively high levels of tobacco CA (Fig. 2), were chosen for these assays (Table I), whereas progeny from line 191–2 were used as transformed negative controls, since the tobacco CA polypeptide was never detected in leaf extracts from any progeny of this line. Soluble-protein and Rubisco content were also measured in leaf extracts from these plants (Table I). On a leaf-area basis, extracts from F. bidentis plants expressing the tobacco CA demonstrated −6 to +60% more CA activity than the negative control plant extracts. However, when Rubisco and soluble-protein content were compared, no appreciable difference was detected between the CA transformants and the controls, nor were any differences in Chl content evident (Table I).

Table I.

Biochemical properties of leaves from F. bidentis control plants and CA transformants

| Plant No. | Rubisco | CA Activity | Soluble Protein | CA Activitya

|

Chl

Content

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole leaf | bscb | Whole leaf | ||||

| μmol m−2 | μmol m−2 s−1 | g m −2 | mol s−1mol−1 Rubisco site | mg g−1 fresh wt | ||

| Controlsc | ||||||

| 191–2.1 | 9.11 | 188 | 4.20 | 22.8 | 1.07 | 0.51 |

| 191–2.4 | 8.38 | 188 | 4.38 | 22.4 | 1.24 | 0.58 |

| 191–2.5 | 8.23 | 148 | 4.42 | n.d.d | n.d. | n.d. |

| CA transformants | ||||||

| 191–7.7 | 8.24 | 197 | 4.16 | 24.8 | 3.19 | 0.60 |

| 191–7.8 | 8.39 | 237 | 4.16 | 34.3 | 5.91 | 0.62 |

| 191–7.6 | 7.82 | 176 | 3.87 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

Experiment in which multiple leaves were used to prepare bundle-sheath strands (see Methods for details).

Corrected for mesophyll contamination (see text for details).

Plants transformed with the tobacco CA construct but not expressing the transgene (see text for details).

n.d., Not determined.

Expression of Tobacco CA in the bsc of F. bidentis CA Transformants

In C4 plants most of the CA is located in the cytosol of the mesophyll cells (Gutierrez et al., 1974; Ku and Edwards, 1975; Burnell and Hatch, 1988), where it catalyzes the hydration of atmospheric CO2 entering the leaf to HCO3−, which is the substrate for the primary carboxylating enzyme of the C4 photosynthetic pathway, PEP carboxylase (Hatch and Burnell, 1990). Very little endogenous CA has been found in the bsc of C4 plants (Burnell and Hatch, 1988), and it has been argued that it is this characteristic absence of CA in the bundle sheath that allows efficient functioning of the C4 pathway (Burnell and Hatch, 1988).

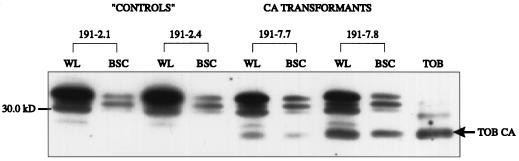

Because the pBI-CA-GUS construct used in the above transformation experiments contained the sequence encoding only the mature form of tobacco CA (i.e. no chloroplast transit peptide sequence was present), and because the CA sequence was under the control of the constitutive CaMV 35S promoter, it was expected that in the transformants the tobacco CA would be expressed in the cytosol of both mesophyll and bsc. To determine whether this was the case, bundle-sheath strands were isolated from plants 191–7.7 and 191–7.8 and from two transformed plants not expressing tobacco CA, 191–2.1 and 191–2.4. Figure 3 and Table I show the results of these experiments. The tobacco CA polypeptide was detected only in the progeny of line 191–7; labeling of the tobacco polypeptide was clearly seen in both the whole-leaf and bsc extracts of plants 191–7.7 and 191–7.8 (Fig. 3). When CA activity was measured on a Rubisco-site basis using aliquots of these extracts, whole-leaf samples from the CA transformants showed a 10% to 50% increase in enzyme activity compared with the negative control plants (Table I). A more striking difference in CA activity was observed between the bsc samples of the controls and the CA transformants; 3 to 5 times more CA activity was measured in the bsc extracts of the CA transformants than in the control samples (Table I).

Figure 3.

Detection of tobacco CA in whole-leaf and bsc extracts of F. bidentis CA transformants. Whole-leaf (WL) and bsc (BSC) extracts from two transformed, negative control F. bidentis plants, 191–2.1 and 191–2.4, and two transformants expressing tobacco CA (TOB CA), 191–7.7 and 191–7.8, were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunolabeled with the anti-tobacco CA antiserum. Equivalent amounts of all of the extracts based on Rubisco content were loaded onto the gels. The position of the 30-kD molecular mass marker is indicated. TOB, Tobacco leaf extract.

The CA activity values reported for the bsc extracts in Table I were corrected for mesophyll contamination using PEP carboxylase as the mesophyll marker enzyme. A maximum mesophyll contamination of 3.5% was estimated for all control and CA transformant bsc preparations. Because this contamination was consistently low in all of the samples, it may reflect the activity of the nonphotosynthetic isoform(s) of PEP carboxylase found in the leaf tissue of Flaveria species (Hermans and Westhoff, 1990).

It is also interesting to note that several of the F. bidentis CA polypeptides were detected in bsc extracts from control plants (Fig. 3). Values of bsc CA activity corrected for mesophyll contamination also suggested that significant amounts of endogenous CA, about 5% of total leaf CA activity, are normally present in the bundle sheath of F. bidentis (Table I). Burnell and Hatch (1988) determined the amount of bsc CA activity for a number of plants representing the three types of C4-decarboxylation pathways. Values averaging 0.65% of total leaf CA activity were found for PEP carboxykinase-type and NAD-ME-type C4 plants, whereas higher estimates of about 1.7% were reported for the NADP-ME-type plants sorghum and maize. F. bidentis is also an NADP-ME-type C4 plant, however, the bsc CA activity determined in the present study is appreciably higher than that of sorghum or maize. The reason(s) for this difference is not immediately apparent and although it may simply be due to a difference in isolation procedures or measurement of enzyme activity, it might reflect a real difference between NADP-ME monocots and dicots, as has been noted for assimilation rates and the ratio of intercellular-to-ambient CO2 partial pressure (Henderson et al., 1992). Both the inter- and intracellular locations of CA in F. bidentis are currently under investigation.

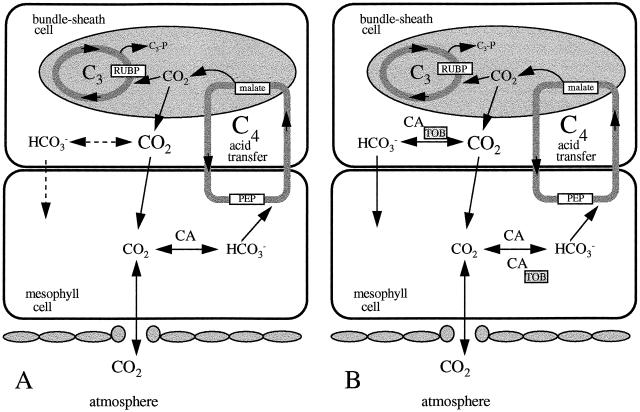

bsc Leakiness Is Increased in the F. bidentis CA Transformants

As mentioned above, both the primary pBI-CA-GUS transformants and their progeny showed no differences in phenotype relative to control plants under the growth conditions employed. However, a physiological difference was expected at the cellular level from introducing the tobacco CA into the bsc cytosol of F. bidentis. The diagrams in Figure 4 show the flow of photosynthetic C in F. bidentis wild-type plants and CA transformants. After malate was decarboxylated in the bsc chloroplasts of wild-type F. bidentis plants (Fig. 4A), much of the released CO2 was fixed by Rubisco. The CO2 that was not fixed diffused out of the chloroplast and back into the mesophyll cells. Very little of this CO2 was converted to HCO3− because relatively low amounts of CA were present in the bsc cytosol (see discussion above). In contrast, the biochemical data presented above indicated that a significant proportion of the tobacco CA was located and active in the bsc of the CA transformants. Thus, in the bsc chloroplasts of these plants (Fig. 4B), the unfixed CO2 released from the decarboxylation of malate diffused out of the chloroplast into the bsc cytosol, where it could then be converted more rapidly to HCO3− due to the introduction of tobacco CA in this compartment. An increase in bsc leakiness is proposed to accompany this shift toward thermodynamic equilibrium, since both CO2 and HCO3− could then diffuse back into the mesophyll cells of the CA transformants.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of photosynthetic C flow in F. bidentis wild-type plants (A) and CA transformants (B). In F. bidentis, an NADP-ME-type C4 plant, CO2 is released from the C4 acid malate in the bundle-sheath chloroplasts. The two schemes differ in the predicted relative amounts of CO2 and HCO3−, which diffuse from the bundle sheath into the mesophyll. The dashed arrows in A denote that CO2 is the major form of inorganic C diffusing back into the mesophyll in wild-type F. bidentis plants. Whereas in the CA transformants (B), inorganic C is lost from the bundle sheath in the form of both CO2 and HCO3− (solid arrows) because of the activity of mature tobacco CA (CATOB) in this compartment. See text for further details. C3-P, Triose-P; and RUBP, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate.

To determine whether the bsc of the CA transformants were more leaky to inorganic C, these plants and the transformed negative controls were characterized using gas-exchange and C isotope discrimination methods. The data in Table II show that the CA transformants demonstrated a 13% to 25% reduction in the C net assimilation rate compared with control plants. However, the similar values of Rubisco content (Table I) and the ratio of intercellular-to-ambient CO2 partial pressure (Table II) obtained for both the controls and the CA transformants show that the decrease in the net assimilation rate was not a result of decreased stomatal conductance or lack of carboxylating enzyme in the CA transformants. Instead, the data are consistent with a reduction in the concentration of CO2 in the bsc being responsible for the observed phenotype.

Table II.

Gas-exchange and C isotope discrimination properties of leaves from F. bidentis control plants and CA transformants

| Plant No. | Assimilation Rate | pi/paa | Δ13C

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short term | Leaf dry matter | |||

| μmol m−2 s−1 | ‰ | |||

| Controlsb | ||||

| 191–2.1 | 36.1 | 0.48 | 2.07 | 5.12 |

| 191–2.4 | 36.7 | 0.42 | 2.70 | 5.12 |

| 191–2.5 | 35.0 | 0.58 | 2.21 | n.d.c |

| CA transformants | ||||

| 191–7.7 | 30.6 | 0.40 | 4.15 | 7.67 |

| 191–7.8 | 29.5 | 0.47 | 4.43 | 8.59 |

| 191–7.6 | 27.5 | 0.58 | 5.0 | 7.77 |

The ratio of intercellular-to-ambient CO2.

Plants transformed with the tobacco CA construct but not expressing the transgene.

n.d., Not determined.

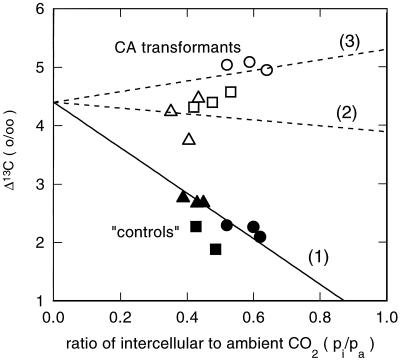

The C isotope discrimination data showed that the CA transformants exhibited appreciable increases in C isotope discrimination (Δ) when Δ was measured both in the short term during gas exchange and on leaf dry matter (Table II). Figure 5 shows the relationship between Δ measured during gas exchange and the ratio of intercellular-to-ambient partial pressure of CO2 (pi/pa) for control and CA transformants. We have used the model of Farquhar (1983) to interpret the data. The model predicts that:

|

where a (4.4‰) is the fractionation during diffusion of CO2 in air (Farquhar et al., 1989). b4 (−5.7‰) is the combined fractionation of PEP carboxylation (2.2‰) and the preceding isotopic equilibrium during dissolution of CO2 and conversion to HCO3−, and assumes that CO2 and HCO3− are close to equilibrium in the mesophyll cytosol. (If this were not the case, then b4 = [−5.7 + 7.9Vp/Vh]‰, where Vp and Vh are the rates of PEP carboxylation and CO2 hydration, respectively.) b3 (30‰) is the fractionation by Rubisco and s is the fractionation during leakage of inorganic C out of the bundle sheath. In the absence of CA in the bundle-sheath cytosol it is usually assumed that s is equal to the fractionation occurring as CO2 dissolves in the bundle sheath and diffuses back to the mesophyll (s = 1.8‰). When CA is present in the bundle-sheath cytosol, however, HCO3− can also diffuse out of the bundle sheath. Since the heavier isotope, 13C, concentrates in HCO3− and Rubisco fixes 12C preferentially, the isotope fractionation associated with leakage increases. Under these conditions s = (5.3α/[1 + 5.3α])(0.4 − 10.1α) + 1.8. Thus, depending on the amount of CA in the bundle sheath, the fractionation factor, s, associated with leakage may vary from 1.8‰, when there is no HCO3− diffusion (α = 0), to −6.3‰, when there is complete equilibrium between CO2 and HCO3− in the bundle-sheath cytosol (α = 1) (Farquhar, 1983; von Caemmerer et al., 1997a).

Figure 5.

Short-term C isotope discrimination (▵) as a function of the intercellular-to-ambient partial pressure of CO2 (pi/pa) in transformed negative control plants (191–2.1, ▪; 191–2.5, •; and 191–2.4, ▴) and F. bidentis plants expressing tobacco CA (191–7.6, ○; 191–7.8, □; and 191–7.7, ▵). The lines are not a fit to the data but depict the theoretically predicted relationship where: Δ = 4.4 + ([30 − s]Φ − 10.1)pi/pa. Slope of line (1) = −3.79; of line (2) = −0.512; and of line (3) = 0.898.

The control plants have C isotope discrimination values similar to those measured previously for F. bidentis (Henderson et al., 1992; von Caemmerer et al., 1997a) and a leakiness value of about 22% is also similar when it is estimated with b4 = −5.7‰ and s = 1.8‰. It is usually assumed that CA is present in sufficient excess in the mesophyll cytosol of C4 species such that b4 = −5.7‰, however, this topic deserves further consideration. For example, Hatch and Burnell (1990) estimated that the rate of CO2 hydration was between 5 and 15 times that of CO2 fixation at ambient CO2 concentrations. Our measurements (Tables I and II) show the CO2 hydration rate to be approximately 5 times that of CO2 fixation for F. bidentis, although this may be an underestimate, since loss of activity of CA may occur during extraction procedures.

The large increase in the C isotope discrimination in the CA transformants indicates that the bsc of these plants are more leaky to inorganic C than control bsc (Table II; Fig. 5). We calculate that the leakiness in the CA transformants may have increased on average to between 28 (s = −6.3‰) and 37%(s = 1.8‰).

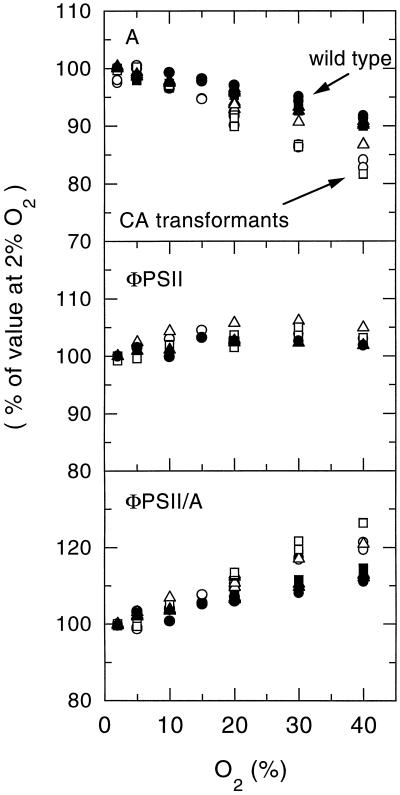

Studies by Dai et al. (1996) have demonstrated that at atmospheric CO2 concentrations, maximal rates of photosynthesis are observed in F. bidentis when O2 concentrations are between 5% and 10%. Inhibition of photosynthesis due to photorespiration occurs at O2 concentrations above this optimum (Dai et al., 1996; Fig. 6A). Due to the increased leakiness of the CA transformant bundle sheath, it was suspected that these plants would show an increased sensitivity to O2 compared with control F. bidentis plants. Plants from the T2 generation of CA transformants were screened by immunoblot analysis for the expression of tobacco CA. The CO2-assimilation rate, the ΦPSII, and the ratio of ΦPSII to A (a measure of the energy required per CO2 molecule fixed) were examined in three individuals exhibiting levels of tobacco CA expression similar to the T1 plants used in the previous experiments (Fig. 6). These characteristics were also determined for three wild-type plants. At the optimal O2 concentration, the CA transformants showed little difference in CO2-assimilation rates relative to wild-type plants (Fig. 6). However, at higher O2 concentrations, the inhibition of photosynthesis was clearly more severe in the transformants than in the wild-type plants (Fig. 6). In contrast, at O2 concentrations above 10%, ΦPSII remained relatively constant for both wild-type plants and the CA transformants (Fig. 6). Consequently, at these O2 levels, CO2 assimilation requires more PSII activity in the CA transformants than in wild-type F. bidentis plants (Fig. 6). These results support the conclusion from the gas-exchange and C isotope discrimination measurements that the bsc of the CA transformants are more leaky to inorganic C than control bsc. Thus, as the partial pressure of O2 increases in the bundle sheath of the CA transformants, the oxygenation reaction of Rubisco is favored to a greater extent than in wild-type plants. This results in the transformants exhibiting higher photorespiration rates and decreased CO2-assimilation rates relative to the wild-type plants at atmospheric O2 concentrations and above.

Figure 6.

O2 dependence of A, ΦPSII, and the ratio of ΦPSII to A in F. bidentis wild-type plants (black symbols) and transgenic plants expressing tobacco CA (white symbols; plants were selected from the T2 progeny of transformant 191–7.8). Measurements were made at an ambient CO2 concentration of 360 μbar, an irradiance of 1000 μmol quanta m−2 s−1, and a leaf temperature of 25°C. Values are expressed as a percentage of values at 2% O2. Mean values at 2% O2 were: A, 32.1 ± 1.3 and 25.8 ± 1.4; ΦPSII, 0.53 ± 0.02 and 0.502 ± 0.01; and ΦPSII/A, 7.2 ± 0.2 and 8.63 ± 0.2 for F. bidentis wild-type plants and transformants, respectively.

Recent studies by Siebke et al. (1997) and Maroco et al. (1998) also examined the O2 sensitivity and ΦPSII of C4 photosynthesis to further characterize plants defective in the C4 cycle, namely PEP carboxylase mutants of Amaranthus edulis and plants with a faulty C3 pathway (i.e. antisense small subunit Rubisco F. bidentis plants). The results of these recent studies, along with those reported here for the CA transformants, indicate that this information is valuable in understanding the interactions of the C3 and C4 cycles in the C4 photosynthetic pathway and the effects on the pathway when the balance between the two interconnected cycles is perturbed.

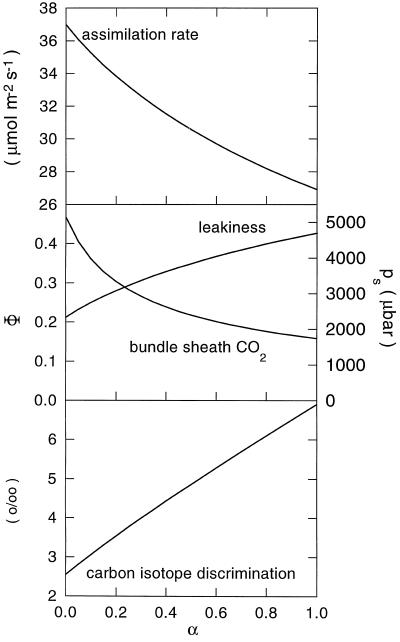

CA Transformants Contain Defective CO2-Concentrating Mechanisms

Early work (Furbank and Hatch, 1987; Burnell and Hatch, 1988) pointed out that the presence of CA in the bundle sheath would lead to inefficient functioning of the C4 pathway. The curves shown in Figure 7 were generated using a mathematical model of C4 photosynthesis (Berry and Farquhar, 1978; von Caemmerer et al., 1997b) and predict what quantitative changes one might expect to observe in CO2-assimilation rate, Δ, and bundle-sheath leakiness and CO2 concentration with respect to decreasing ratios of CO2 to HCO3− in the bundle-sheath cytosol.

Figure 7.

Predicted changes in the CO2-assimilation rate, bundle-sheath leakiness (Φ) and CO2 partial pressure (ps), and C isotope discrimination, with changes in the degree of CO2 and HCO3− equilibration in the bundle-sheath cytosol (α = 1 at full equilibration between CO2 and HCO3−). Calculations were made with the mathematical model of C4 photosynthesis described by von Caemmerer et al. (1997b) at an intercellular CO2 partial pressure of 150 μbar, a maximal Rubisco activity of 50 μmol m−2 s−1, a maximal PEP carboxylase activity of 72 μmol m−2 s−1, and a bundle-sheath conductance (gs) of 2 (1 + 5.3 α) mmol m−2 s−1. C isotope discrimination was calculated from Δ = 4.4 + ([30 − s]Φ − 10.1)pi/pa, with pi/pa = 0.45 and s = 1.8 − 10.1(5.3α2/[1 + 5.3α]).

Farquhar (1983) considered a simplified system with uniform pH where interconversion of CO2 and HCO3− takes place in the mesophyll and bsc but not in the symplastic transport path. He showed that the bundle-sheath conductance to leakage of total inorganic C could be given by:

|

where gsc is the bundle-sheath conductance to CO2 diffusion alone and the diffusivity of HCO3− in water, Db, is 0.56 times that of CO2, Dc, at 25°C (Kigoshi and Hashitani, 1963). The dissociation constant K for HCO3− is 10−6.12 at 25°C and an ionic strength of 0.1 (Harned and Bonner, 1945). Therefore, at a cytoplasmic pH of 7.4, gs = gsc (1 + 10.67α lc/lb). Jenkins et al. (1989) inferred from metabolite transport measurements that the effective path length for HCO3− diffusion, lb, is approximately twice that of CO2, lc. Thus a 6- to 7-fold increase in bundle-sheath conductance is seen as α varies from 0 to 1. This increase in conductance is reflected in the decrease in A and bundle-sheath CO2 partial pressure and in the increase in bsc leakiness and C isotope discrimination values. With the chosen parameters the model predicts that even at complete equilibrium of HCO3− and CO2 in the bsc cytosol, the CO2-assimilation rate would be decreased by only 30%, which would be accompanied by a 2.5-fold increase in C isotope discrimination. In line with these predictions, our data show that the modest reduction in CO2-assimilation rate demonstrated by the CA transformants was accompanied by a doubling of short-term C isotope discrimination (Table II). Jenkins et al. (1989) came to a similar conclusion with respect to CA activity in the bundle-sheath cytosol. Their model predicted that even a 1000-fold increase in CA activity (over the nonenzymatic rate) in the cytosol of the bundle sheath would not have a major effect on the bsc CO2 concentration or C4 acid pathway overcycling.

CONCLUSIONS

Previously, biochemical and modeling studies have shown that an absence of CA in the bundle sheath of C4 plants is requisite for the effective functioning of the C4 photosynthetic pathway (Furbank and Hatch, 1987; Burnell and Hatch, 1988). As discussed above, however, the modeling study of Jenkins et al. (1989) suggested that the presence of some CA in the bundle sheath would not be as detrimental to the efficiency of C4 photosynthesis as previously believed. In the present study perturbation of the CO2-concentrating mechanism of F. bidentis was attempted by expressing mature tobacco CA in the mesophyll and bsc cytosol. The biochemical and physiological characteristics of the resulting CA transformants indicated that the CO2-concentrating mechanism of these plants was less efficient than that of the controls. However, no obvious phenotypic differences were detected between the CA transformants, wild-type plants, and the transformed negative controls in any of the three generations of plants studied.

The expression of tobacco CA in the bundle sheath of F. bidentis resulted in the bsc of the CA transformants containing 3 to 5 times more CA activity than control bsc, and an increase in C isotope discrimination was measured in the CA transformants both in the short term during gas exchange and on leaf dry matter. Moreover, the CA transformants demonstrated reduced net CO2-assimilation rates relative to the controls. In light of the relationship predicted between C isotope discrimination and bsc leakiness (Farquhar, 1983), these data indicate that increasing the CA activity in the bundle-sheath cytosol of F. bidentis resulted in plants that are partially defective in the C4 CO2-concentrating mechanism due to increased permeability of the bundle sheath to inorganic C. O2 sensitivity and ΦPSII measurements from the CA transformants and wild-type plants also indicated that the availability of CO2 for fixation by Rubisco in the bsc was decreased in the transformants, and that at supraoptimal O2 levels, the effectiveness of the C4 pathway in the transformants was compromised. The indication that the bundle sheath of F. bidentis contains more endogenous CA activity than the bsc of other C4 plants and the intracellular location of this enzyme activity are currently under further investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the expertise and assistance of Julie Chitty with the F. bidentis transformation system. We also thank Anthony Millgate and Karin Harrison for their valuable technical support.

Abbreviations:

- A

CO2 assimilation

- bsc

bundle-sheath cell(s)

- CA

carbonic anhydrase

- CaMV

cauliflower mosaic virus

- Chl

chlorophyll

- ME

malic enzyme

- ΦPSII

quantum yield of PSII

LITERATURE CITED

- Atkins CA, Patterson BD, Graham D. Plant carbonic anhydrases. I. Distribution of types among species. Plant Physiol. 1972;50:214–217. doi: 10.1104/pp.50.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Price GD. Carbonic anhydrase activity associated with the cyanobacterium Synechococcus PCC7942. Plant Physiol. 1989;89:51–60. doi: 10.1104/pp.89.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry J, Farquhar G (1978) The CO2 concentrating function of C4 photosynthesis: a biochemical model. In D Hall, J Coombs, TW Goodwin, eds, Proceedings of the Fourth International Congress on Photosynthesis. Biochemical Society, London, pp 119–131

- Burnell JN, Gibbs MJ, Mason JG. Spinach chloroplastic carbonic anhydrase. Nucleotide sequence analysis of cDNA. Plant Physiol. 1990;92:37–40. doi: 10.1104/pp.92.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnell JN, Hatch MD. Low bundle sheath carbonic anhydrase is apparently essential for effective C4 pathway operation. Plant Physiol. 1988;86:1252–1256. doi: 10.1104/pp.86.4.1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnell JN, Ludwig M. Characterisation of two cDNAs encoding carbonic anhydrase in maize leaves. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1997;24:451–458. [Google Scholar]

- Butz ND, Sharkey TD. Activity ratios of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase accurately reflect carbamylation ratios. Plant Physiol. 1989;89:735–739. doi: 10.1104/pp.89.3.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitty JA, Furbank RT, Marshall JS, Chen Z, Taylor WC. Genetic transformation of the C4 plant, Flaveria bidentis. Plant J. 1994;6:949–956. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan IR. Economics of carbon fixation in higher plants. In: Givinish TJ, editor. On the Economy of Plant Form and Function. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1986. pp. 133–170. [Google Scholar]

- Dai Z, Ku MSB, Edwards GE. Oxygen sensitivity of photosynthesis and photorespiration in different photosynthetic types in the genus Flaveria. Planta. 1996;198:563–571. doi: 10.1007/BF00262643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD. On the nature of carbon isotope discrimination in C4 species. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1983;10:205–226. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Ehleringer JR, Hubick KT. Carbon isotope discrimination and photosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1989;40:503–537. [Google Scholar]

- Fett JP, Coleman JR. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:707–713. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.2.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furbank RT, Chitty JA, Jenkins CLD, Taylor WC, Trevanion SJ, von Caemmerer S, Ashton AR. Genetic manipulation of key photosynthetic enzymes in the C4 plant Flaveria bidentis. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1997;24:477–485. [Google Scholar]

- Furbank RT, Hatch MD. Mechanism of C4 photosynthesis. The size and composition of the inorganic carbon pool in bundle sheath cells. Plant Physiol. 1987;85:958–964. doi: 10.1104/pp.85.4.958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genty B, Briantais J-M, Baker NR. The relationship between the quantum yield of photosynthetic electron transport and quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;990:87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez M, Huber SC, Ku SB, Kanai R, Edwards GE. Intracellular localization of carbon metabolism in mesophyll cells of C4 plants. In: Avron M, editor. Proceedings of the Third International Congress on Photosynthesis. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers; 1974. pp. 1219–1230. [Google Scholar]

- Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies. A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Harned HS, Bonner FT. The first ionization of carbonic acid in aqueous solutions of sodium chloride. J Am Chem Soc. 1945;67:1026–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch MD. C4 photosynthesis: a unique blend of modified biochemistry, anatomy and ultrastructure. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;895:81–106. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch MD, Burnell JN. Carbonic anhydrase activity in leaves and its role in the first step of C4 photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 1990;93:825–828. doi: 10.1104/pp.93.2.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson SA, von Caemmerer S, Farquhar GD. Short-term measurements of carbon discrimination in several C4 species. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1992;19:263–285. [Google Scholar]

- Hermans J, Westhoff P. Analysis of expression and evolutionary relationships of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase genes in Flaveria trinervia (C4) and F. pringlei (C3) Mol Gen Genet. 1990;224:459–468. doi: 10.1007/BF00262441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson BS, Fong F, Heath RL. Carbonic anhydrase of spinach. Studies on its location, inhibition, and physiological function. Plant Physiol. 1975;55:468–474. doi: 10.1104/pp.55.3.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins CLD, Furbank RT, Hatch MD. Mechanism of C4 photosynthesis. A model describing the inorganic carbon pool in bundle sheath cells. Plant Physiol. 1989;91:1372–1381. doi: 10.1104/pp.91.4.1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson I-M, Forsman C. Processing of the chloroplast transit peptide of pea carbonic anhydrase in chloroplasts and Escherichia coli: identification of two cleavage sites. FEBS Lett. 1992;314:232–236. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81478-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kigoshi K, Hashitani T. The self-diffusion coefficients of carbon dioxide, hydrogen carbonate ions and carbonate ions in aqueous solutions. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1963;36:1372. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak M. Comparison of initiation of protein synthesis in procaryotes, eucaryotes, and organelles. Microbiol Rev. 1983;47:1–45. doi: 10.1128/mr.47.1.1-45.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku SB, Edwards GE. Photosynthesis in mesophyll protoplasts and bundle sheath cells of various types of C4 plants. V. Enzymes of respiratory metabolism and energy utilizing enzymes of photosynthetic pathways. Z Pflanzenphysiol. 1975;77:16–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig M, Burnell JN. Molecular comparison of carbonic anhydrase from Flaveria species demonstrating different photosynthetic pathways. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;29:353–365. doi: 10.1007/BF00043658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunn JE, Furbank RT. Localisation of sucrose-phosphate synthase and starch in leaves of C4 plants. Planta. 1997;202:106–111. doi: 10.1007/s004250050108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majeau N, Coleman JR. Isolation and characterization of a cDNA coding for pea chloroplastic carbonic anhydrase. Plant Physiol. 1991;95:264–268. doi: 10.1104/pp.95.1.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majeau N, Coleman JR. Nucleotide sequence of a complementary DNA encoding tobacco chloroplastic carbonic anhydrase. Plant Physiol. 1992;100:1077–1078. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.2.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroco JP, Ku MSB, Lea PJ, Dever LV, Leegood RC, Furbank RT, Edwards GE. Oxygen requirement and inhibition of C4 photosynthesis. An analysis of C4 plants deficient in the C3 and C4 cycles. Plant Physiol. 1998;116:823–832. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.2.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mate CJ, Hudson GS, von Caemmerer S, Evans JR, Andrews TJ. Reduction of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase activase levels in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) by antisense RNA reduces ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase carbamylation and impairs photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 1993;102:1119–1128. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.4.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister M, Agostino A, Hatch MD. The roles of malate and aspartate in C4 photosynthetic metabolism of Flaveria bidentis (L.) Planta. 1996;199:262–269. [Google Scholar]

- Okabe K, Yang S-Y, Tsuzuki M, Miyachi S. Carbonic anhydrase: its content in spinach leaves and its taxonomic diversity studied with anti-spinach leaf carbonic anhydrase antibody. Plant Sci Lett. 1984;33:145–153. [Google Scholar]

- Poincelot RP. Intracellular distribution of carbonic anhydrase in spinach leaves. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;258:637–642. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(72)90255-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porra RJ, Thompson WA, Kriedemann PE. Determination of accurate extinction coefficients and simultaneous equations for assaying chlorophylls a and b extracted with four different solvents: verification of the concentration of chlorophyll standards by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;975:384–394. [Google Scholar]

- Price GD, von Caemmerer S, Evans JR, Yu J-W, Lloyd J, Oja V, Kell P, Harrison K, Gallagher A, Badger MR. Specific reduction of chloroplast carbonic anhydrase activity by antisense RNA in transgenic tobacco plants has a minor effect on photosynthetic CO2 assimilation. Planta. 1994;193:331–340. [Google Scholar]

- Price GD, Yu J-W, von Caemmerer S, Evans JR, Chow WS, Anderson JM, Hurry V, Badger MR. Chloroplast cytochrome b6/f and ATP synthase complexes in tobacco: transformation with antisense RNA against nuclear-encoded transcripts for the Rieske FeS and ATPδ polypeptides. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1995;22:285–297. [Google Scholar]

- Provart NJ, Majeau N, Coleman JR. Characterization of pea chloroplastic carbonic anhydrase: expression in Escherichia coli and site-directed mutagenesis. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;22:937–943. doi: 10.1007/BF00028967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed ML, Graham D. Carbonic anhydrase in plants: distribution, properties and possible physiological roles. In: Reinhold L, Harborne JB, Swain T, editors. Progress in Phytochemistry, Vol 7. Oxford, UK: Pergammon Press; 1981. pp. 47–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rumeau D, Cuiné S, Fina L, Gault N, Nicole M, Peltier G. Subcellular distribution of carbonic anhydrase in Solanum tuberosum L. leaves. Planta. 1996;199:79–88. doi: 10.1007/BF00196884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebke K, von Caemmerer S, Badger MR, Furbank RT. Expressing an RbcS antisense gene in transgenic Flaveria bidentis leads to an increased quantum requirement per CO2 fixed in photosystem I and II. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:1163–1174. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.3.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuzuki M, Miyachi S, Edwards GE. Localization of carbonic anhydrase in mesophyll cells of terrestrial C3 plants in relation to CO2 assimilation. Plant Cell Physiol. 1985;26:881–891. [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Evans JR. Determination of the average partial pressure of CO2 in chloroplasts from leaves of several C3 plants. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1991;18:287–305. [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Ludwig M, Millgate A, Farquhar GD, Price D, Badger M, Furbank RT. Carbon isotope discrimination during C4 photosynthesis: in sights from transgenic plants. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1997a;24:487–494. [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Millgate A, Farquhar GD, Furbank RT. Reduction of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase by antisense RNA in the C4 plant Flaveria bidentis leads to reduced assimilation rates and increased carbon discrimination. Plant Physiol. 1997b;113:469–477. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.2.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]