Abstract

Spraying potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) leaves with arachidonic acid (AA) at 1500 μg mL−1 led to a rapid local synthesis of salicylic acid (SA) and accumulation of a SA conjugate, which was shown to be 2-O-β-glucopyranosylsalicylic acid. Radiolabeling studies with untreated leaves showed that SA was synthesized from phenylalanine and that both cinnamic and benzoic acid were intermediates in the biosynthesis pathway. Using radiolabeled phenylalanine as a precursor, the specific activity of SA was found to be lower when leaves were treated with AA than in control leaves. Similar results were obtained when leaves were fed with the labeled putative intermediates cinnamic acid and benzoic acid. Application of 2-aminoindan-2-phosphonic acid at 40 μm, an inhibitor of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase, prior to treatment with AA inhibited the local accumulation of SA. When the putative intermediates were applied to leaves in the presence of 2-aminoindan-2-phosphonic acid, about 40% of the expected accumulation of free SA was recovered, but the amount of the conjugate remained constant.

Since the discovery that SA is produced upon infection of cucumber (Métraux et al., 1990) or tobacco (Malamy et al., 1990) leaves prior to the expression of systemic resistance, much effort has been devoted to demonstrate the role of SA in the resistance of plants to disease (Raskin, 1992; Delaney et al., 1994). SA was originally proposed as a putative signaling molecule for the induction of SAR on the basis of the results obtained with cucumber (Métraux et al., 1990; Rasmussen et al., 1991) and tobacco (Malamy et al., 1990; Enyedi et al., 1992; Malamy and Klessig, 1992). In tobacco the same defense-related genes that were expressed locally and systemically upon infection with tobacco mosaic virus were also activated by treatment with SA (Ward et al., 1991). More recent results have shown that transgenic tobacco plants expressing bacterial salicylate hydroxylase, which metabolizes SA, are unable to express SAR and even show enhanced susceptibility to pathogens (Gaffney et al., 1993). SAR was restored in wild-type scions grafted onto a transgenic rootstock, indicating that SA may not be the primary mobile signal but a necessary component for SAR (Vernooij et al., 1994a). It has been suggested that SA is required for signal transduction at the local level and that its mode of action may include inhibition of catalase activity, leading to increased levels of H2O2 (Vernooij et al., 1994b).

Rapid production of H2O2 (oxidative burst) upon treatment of plants with elicitors or upon inoculation with avirulent pathogens may act as a local trigger of programmed cell death (Levine et al., 1994), which very often precedes SAR, but in tobacco leaves expressing SAR no increase in H2O2 was detected (Ryals et al., 1995). It has also been shown in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) that treatment with the biotic elicitor AA, which induces SAR (Cohen et al., 1991; Coquoz et al., 1995), only gives rise to local accumulation of SA (Coquoz et al., 1995) and that in rice no changes in SA occur upon inoculation with pathogens (Silverman et al., 1995). However, both in potato (Coquoz et al., 1995) and in rice (Silverman, 1995), there appears to be a direct correlation between the amount of endogenous SA and resistance to pathogens. Moreover, in potato expressing the NahG gene, induced resistance is strongly decreased, indicating that SA might also be a necessary component in the induction for SAR in potato (Yu et al., 1997). Clearly, information on the pathway leading to the synthesis of SA and the fate of endogenous or exogenous SA is important for an understanding of the way in which SA is related to SAR.

Early studies showed that in higher plants SA derives from the shikimate-phenylpropanoid pathway (Zenk and Müller, 1964). Two routes from Phe to SA have been found that differ at the step involving hydroxylation of the aromatic ring: Phe is converted into CA by PAL and the latter is either hydroxylated to form ortho-coumaric acid followed by oxidation of the side chain (El-Basyouni et al., 1964; Chadha and Brown, 1974), or the side chain of CA is initially oxidized to give BA, which is then hydroxylated in the ortho position (Zenk and Müller, 1964; Ellis and Amrhein, 1971). When BA was fed to various plants, the synthesis of SA, and particularly of a glucosyl conjugate of SA, was observed (Klämbt, 1962). More recently, Yalpani et al. (1993) have shown that in tobacco SA is synthesized via BA and that healthy tobacco leaves contain a large pool of conjugated BA. BA 2-hydroxylase was detected in the leaves of healthy plants and the activity increased significantly upon inoculation with tobacco mosaic virus (Léon et al., 1993). In cucumber leaves radiolabeling studies showed that SA is synthesized locally and systemically from Phe upon inoculation with tobacco necrosis virus or Pseudomonas lachrymans (Meuwly et al., 1995).

The fate of SA in plants has also been studied (for review, see Lee et al., 1995); glycosides, esters, and amide conjugates have been identified in different plants, but the major conjugate is usually 2-O-β-glucopyranosyl SA. In some cases, dihydroxybenzoic acids were also formed from SA. In tobacco decarboxylation of SA was detected, and it was suggested that glucoside formation precedes decarboxylation (Edwards, 1994). Hydroxy-BAs were rapidly decarboxylated by peroxidase in cell-suspension cultures of some leguminous plants, but both SAs and BAs were preferentially glycosylated to form ester conjugates and were thereby protected against oxidative carboxylation (Barz et al., 1978).

With the exception of rice (Silverman et al., 1995) and potato (Coquoz et al., 1995), most of the plants in which the relationship between SA and SAR has been studied do not contain much endogenous SA. In this paper we report results on the biosynthesis of SA in healthy potato leaves and in leaves treated with AA in which SA production is strongly induced.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture of the Plants and the Pathogen

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L. cv Bintje) plants were propagated in vitro from a clone obtained from the Swiss Federal Agronomy Station (Changins, Nyon, Switzerland) as previously described (Coquoz et al., 1995). Phytophthora infestans (isolate 191, race 1, 2, 3; mating-type A1) was cultured and plants were inoculated as described previously (Coquoz et al., 1995).

Treatment of the Plants with AA

The third leaf of 4-week-old plants was excised with a razor blade and the petiole was immediately immersed in deionized water. The leaves were sprayed with a sonicated suspension of AA (1500 μg mL−1) as described by Cohen et al. (1991) and the plants were maintained at room temperature. Control plants were sprayed with deionized water.

Radiolabeling Experiments

Two hours after the treatment with AA, the leaves were transferred to aqueous solutions (20 μL) containing one of the following labeled substances: [U-14C]BA (20 nCi, 13 mCi mmol−1; Sigma), [3-14C]CA (20 nCi, 53.88 mCi mmol−1; Isotopchim, Ganagobie-Peyruis, France), or [ring U-14C]Phe (20 nCi, 116 mCi mmol−1; Amersham). After 30 min the plants were returned to deionized water. When appropriate, plants were treated with an aqueous solution of AIP (40 μm) 1 h before the treatment with AA. Labeling experiments were carried out at least twice with similar results.

Leaf Disc Experiments

Two hours after treatment of leaf 3 with AA or water, leaf discs (13 mm in diameter) were punched out and immediately vacuum infiltrated with buffer solution (100 mm sodium acetate, pH 5.5) containing radiolabeled precursors: [U-14C]BA (20 nCi, 13 mCi mmol−1; Sigma) or [ring U-14C]Phe (20 nCi, 116 mCi mmol−1; Amersham) as described by Meuwly et al. (1995).

Extraction and Analysis of Phenolic Compounds by HPLC

Phenolic compounds were identified and quantified as described by Meuwly and Métraux (1993) with the following modifications. Three-hundred nanograms of the internal standard (o-anisic acid) was added per sample. Samples were resuspended in 400 or 800 μL of the starting mobile phase (15% [v/v] acetonitrile in 10 mm KH2PO4, pH 3.5) for free and conjugated phenolic compounds, respectively. Samples (80 μL for free or 60 μL for conjugated phenolic compounds) were separated on a deactivated reverse-phase column (25 cm × 0.4 mm, LC-SAL, Supelco, Bellefonte, PA).

Identification of SA and Conjugate by GC-MS

Plant material was extracted with 70% ethanol as described above, and the organic phase evaporated in vacuo to dryness. The material was dissolved in anhydrous pyridine (100 μL) and N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide containing 1% trimethylchlorosilane (100 μL) was added. The mixture was heated (30 min, 80°C), evaporated to dryness, and redissolved in n-hexane (20 μL). Samples (5 μL, splitless) were taken for analysis by GC-MS (HP 5890 coupled to a 5970 mass specific detector, Hewlett-Packard). Separations were carried out on a capillary column (25 m × 0.22 mm × 0.25 μm) coated with methyl silicone (BP5X, SGE, Melbourne) using He carrier gas at 1 mL min−1. The injection port and the ion source were maintained at 200°C and 290°C, respectively; the initial temperature was held at 140°C for 2 min and then programmed at 4°C min−1 to 290°C. MS analysis was carried in the electron-impact mode at an ionizing potential of 70 eV. The per-trimethylsilyl derivative of authentic 2-O-β-glucopyranosyl SA, a gift from D.F. Klessig (Waksman Institute, Rutgers, NJ) (Hennig et al., 1993), eluted at 36 min. Other phenolic substances were identified by comparison of their retention time and mass spectrum with those of authentic standards.

An aliquot of the extract was incubated with β-glucosidase from almond emulsin (Fluka) in sodium acetate buffer (50 mm, pH 5.5, 12 h) and analyzed as above.

Determination of PAL Activity

Plant material was homogenized in liquid N2 and suspended (5 g mL−1 fresh weight) in extraction buffer (100 mm sodium tetraborate, pH 8.8) containing 10 mm DTT and 50 mg mL−1 PVP. After centrifugation (20,000g; 15 min), the supernatant was freed of low-Mr plant material on a column of Sephadex G-25 equilibrated with extraction buffer containing 20% (v/v) glycerol, but without PVPP. Extract (200 μL) was added to 100 mm borate buffer (pH 8.8) containing 10 mm DTT, 60 mm Phe, and [ring U-14C]Phe (116 mCi mmol−1). The mixture was incubated (1 h, 30°C) and the reaction stopped by the addition of 6 m HCl (100 μL). The reaction products were partitioned with ethylacetate (1.3 mL) and the radioactivity (CA) in the organic phase was counted by liquid scintillation.

RESULTS

Identification of SA, 2-O-β-Glucopyranosyl SA, and Other Phenolic Compounds in Potato Leaves

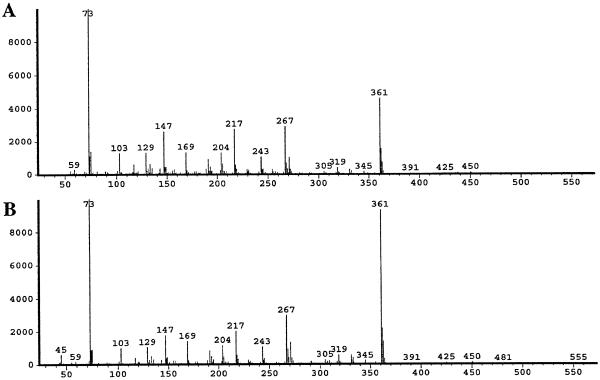

HPLC of acidic compounds from potato leaves soluble in aqueous methanol showed the presence of SA, BA, ferulic acid, caffeic acid, or CA. The presence of these compounds inter alia was confirmed by GC-MS analysis of their pertrimethylsilyl derivatives (not shown). The presence of SA conjugates was established by measuring an increase in the amount of free SA after acid hydrolysis of the material. The identity of the SA conjugate as 2-O-β-glucopyranosyl SA was established by comparison of the retention time and electron-impact mass spectrum (Fig. 1) of the pertrimethylsilyl derivative with those of an authentic sample, which was chemically synthesized and characterized (Grynkiewicz et al., 1993). It should be noted, however, that the mass spectrum is not very informative, since the major ion fragments derive from the sugar moiety. Treatment with a β-glucosidase from almond emulsion followed by analysis by GC-MS showed that complete hydrolysis of the putative glucoside had taken place and that SA was released. The presence of significant amounts of other SA conjugates was negligible, since treatment of extracts with 1 m NaOH at room temperature (saponification of ester conjugates) did not release SA and treatment with 7 m NaOH at 100°C (hydrolysis of amide conjugates) did not give more SA than acid hydrolysis (hydrolysis of glycoside conjugates).

Figure 1.

A, Electron-impact mass spectrum of the pertrimethylsilyl derivative of putative salicylglucopyranoside (retention time, 35.95 min on gas-liquid chromatography) in extracts of potato leaves treated with 1500 μg mL−1 AA. B, Electron-impact mass spectrum of the pertrimethylsilyl derivative of authentic salicylglucopyranoside (retention time, 36 min).

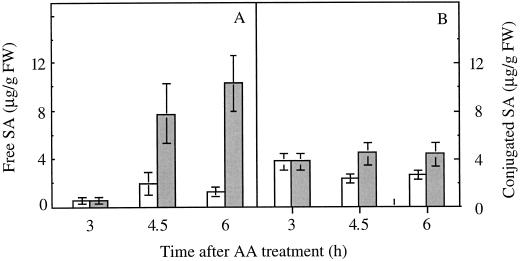

Accumulation of SA in Detached Potato Leaves after Treatment with AA

When detached potato leaves from 4-week-old plants were sprayed with a suspension of AA (1500 μg mL−1), free SA began to accumulate after 4 h to reach a maximum (11 μg g−1 fresh weight) after 6 h (Fig. 2). In the same time period no significant increase in the amount of conjugated SA was observed.

Figure 2.

Level of free (A) and conjugated (B) SA in control (white bars) and AA-treated (shaded bars) potato leaves. Detached leaves were treated with water (control) or 1500 μg mL−1 of AA. Results are means ± se of three replicates. FW, Fresh weight.

Phe as a Precursor for the Synthesis of SA

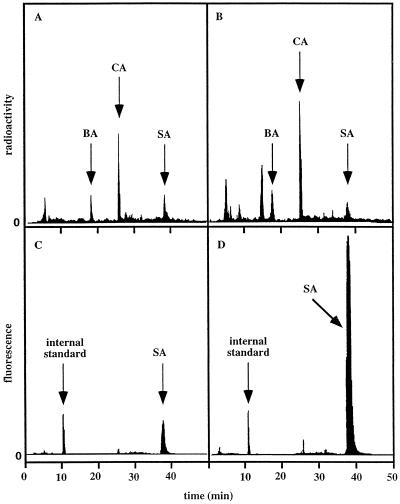

When detached leaves were fed [14C]Phe, radioactivity was found to accumulate in components that were chromatographically (HPLC) identical to CA, BA, and SA (Fig. 3), suggesting that CA and BA were intermediates in the biosynthetic pathway to SA.

Figure 3.

HPLC chromatograms showing incorporation of radioactivity from [14C]Phe into CA, BA, and SA in control (A) and treated (B) leaves, as well the amounts of SA synthesized in control (C) and treated (D) leaves 6 h after treatment.

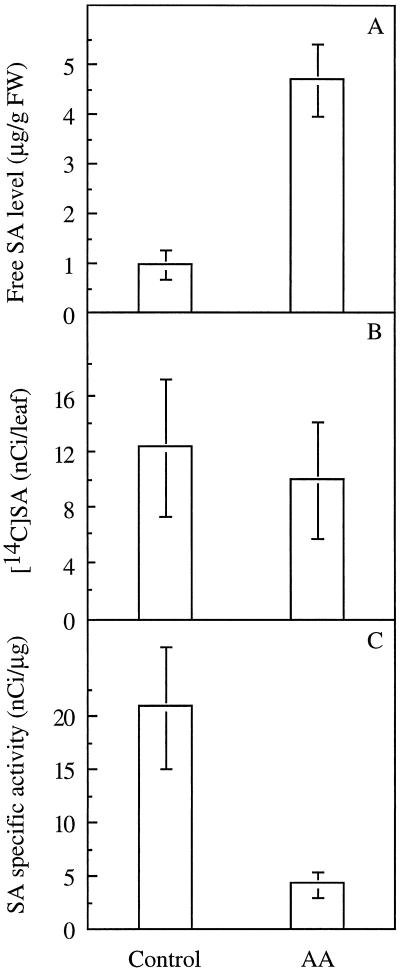

Treatment with AA of leaves fed with the same amounts of [14C]Phe had no marked effect on the amount of total radioactivity taken up in leaves and led to the accumulation of similar amounts of radioactivity in the free SA of control leaves (12.4 ± 4.9 nCi per leaf) when compared with leaves treated with AA (10.1 ± 4.13 nCi per leaf). However, the specific activity of the free SA in the untreated leaves was markedly higher (20.8 ± 5.7 nCi μg−1) than in AA-treated leaves (4.21 ± 1.2 nCi μg−1) (Fig. 4), suggesting that not all of the free SA that accumulated after treatment with AA derived directly from the radioactive pool of Phe. The amount of conjugated SA did not decrease after treatment with AA, showing that the decrease in the specific activity of the free SA was not due to hydrolysis of conjugated SA (Fig. 2).

Figure 4.

Levels of free SA (A), radioactivity in SA (B), and specific activity of free SA (C) in detached leaves treated with deionized water (control) or AA and fed with [14C]Phe. Results are means ± se of three replicates. FW, Fresh weight.

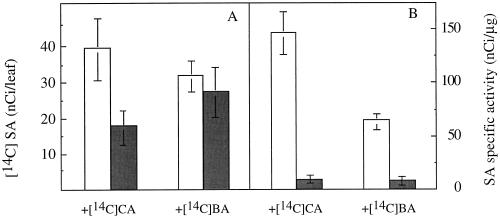

CAs and BAs as Intermediates for the Synthesis of SA

To confirm the role of CA as an intermediate in the path from Phe to SA, labeled CA was fed to potato leaves under the conditions described above. After 6 h, less radioactivity was found in SA of the treated leaves (17.6 ± 5.1 nCi per leaf) than in the control leaves (39.2 ± 8.5 nCi per leaf) and the specific activity of the free SA decreased from 145.9 ± 19.5 nCi μg−1 in the control leaves to 7.86 ± 0.2 nCi μg−1 in the treated leaves (Fig. 5). However, radioactivity was also found in free BA both in the control (22.95 ± 2.3 nCi/leaf) and in treated (23.2 ± 1.3 nCi/leaf) leaves. It is clear that some of the radioactivity also followed the lignin pathway. Analogous experiments were carried out using labeled BA. There was no marked difference between control (31.7 ± 4.4 nCi per leaf) and treated (27.2 ± 7.2 nCi per leaf) leaves in the radioactivity incorporated into free SA, but the specific activity of the free SA was higher in the control leaves (62.9 ± 7.4 nCi μg−1) than in the treated leaves (6.9 ± 1.9 nCi μg−1). When carboxyl-labeled BA was used instead of ring-labeled BA, similar results were obtained, indicating that no decarboxylation process occurred in the transformation of BA to SA (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Levels of radioactivity (A) and specific activity (B) of free SA in detached leaves treated with deionized water (control) or AA and fed within control (white bars) and AA-treated (gray bars) potato leaves fed with [14C]CA or [14C]BA. Results are means ± se of three replicates.

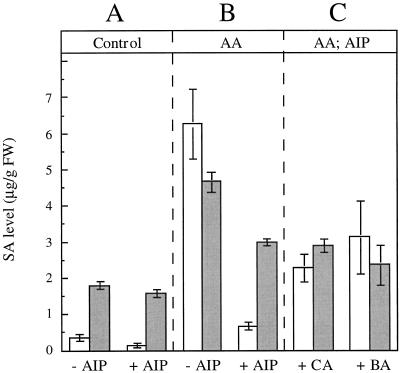

The Role of PAL in the Synthesis of SA

Since incorporation of radioactivity into SA occurs when both labeled Phe and CA are fed to leaves, the role of PAL merited closer attention. The activity of PAL in leaf homogenates was determined and the effect of prior application of the specific inhibitor AIP (Zon and Amrhein, 1992) was measured. PAL activity was almost completely inhibited at concentrations greater than 20 μm. Petiole feeding of AIP was carried out 2 h before treatment of the leaves with AA, corresponding to the optimal condition for inhibition in planta. No difference in the amount of SA, either in the free or conjugated form, was found in the presence of AIP in control leaves after 6 h (Fig. 6A). However, the amounts of both free and conjugated SA in leaves treated with AA in the presence of AIP were lower than in leaves treated with AA in the absence of AIP (Fig. 6B). Feeding CA or BA to leaves 2 h after treatment with AA in the presence of AIP gave rise to the accumulation of free SA, but only about 40% of the amount measured in leaves treated with AA in the absence of AIP (Fig. 6C). This low value may be due of the fact that when fed CA or especially BA, plants rapidly produce substantial amounts of the corresponding conjugate (data not shown), which is then unavailable for the synthesis of SA.

Figure 6.

Levels of free (white bars) and conjugated (gray bars) SA in detached potato leaves 6 h after treatment with deionized water (A) or AA (B). Leaves (B and C) were fed with AIP (20 μm) 1 h before treatment. CA (3.4 mm) or BA (8.2 mm) was added 2 h after treatment (C). Results are means ± se of three replicates. FW, Fresh weight.

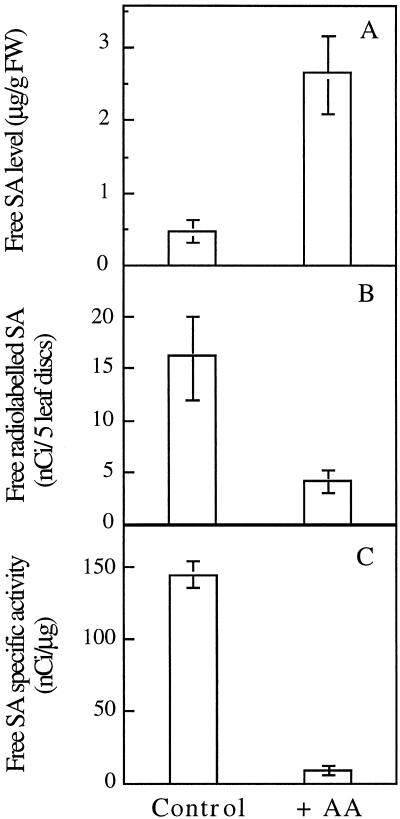

Experiments with Leaf Discs

To verify that the results obtained above were not dependent on the labeling procedure by petiole uptake, we decided to use vacuum-infiltrated leaf discs as an alternative. Figure 7 shows that when leaf discs were treated with AA, they produced more SA than controls (Fig. 7A). Again it was observed that the specific activity of the SA in treated leaves was significantly lower than in control leaves. Other preliminary experiments showed that the leaf discs behaved similarly to the detached leaves (data not shown) and it was therefore concluded that the results obtained with the latter gave valid information concerning the biosynthesis of SA and were not artifacts.

Figure 7.

Leaf disc experiment. Levels of free SA (A), radiolabeled SA (B), and SA specific activity (C) were measured 6 h after AA treatment. Radiolabeled CA was vacuum infiltrated 2 h after AA treatment. Results are means ± se of three replicates. FW, Fresh weight.

DISCUSSION

Treatment of potato leaves with AA has been shown to induce SAR against subsequent infections with P. infestans or Alternaria solani (Cohen et al., 1991; Coquoz et al., 1995). Application of AA also leads to a substantial accumulation of SA that remains limited to the treated areas of the plant (Coquoz et al., 1995). We have now examined the biochemical pathway leading to the production of SA after treatment with AA and compared it with the pathway in untreated, healthy plants.

Radiolabeled SA was detected after feeding plants, both untreated and treated with AA, with [U-14C]Phe, [U-14C]CA, or [U-14C]BA, indicating that the pathway from Phe via CA and BA functions in potato. This was confirmed by the finding that both CA and BA were labeled upon feeding Phe as a precursor. No radiolabeled o-coumaric acid was found when using labeled Phe or CA as precursors (data not shown), showing that the pathway from Phe to SA proceeds mainly via BA, as is the case for tobacco (Yalpani et al., 1993) and cucumber (Meuwly et al., 1995). However, irrespective of the labeled precursor used, the specific activity of SA was found to be considerably lower in the plants treated with AA than in the untreated, control plants. The reduction was not due to an inhibition of uptake of the precursors, since in all cases the pretreatment with AA had no marked effect on the amount of radioactivity found in the metabolites. This suggests that at least some of the SA produced in leaves from plants treated with AA might derive from an alternative pathway or may result in an inefficient tissue distribution of the labeled precursors that were fed via the petiole. To rule out the latter possibility we also carried out experiments using vacuum-infiltrated leaf discs (compare with Meuwly et al., 1995). Using [U-14C]CA as a precursor, these experiments showed essentially the same dilution of specific activity as that observed after petiole feeding (Fig. 7). Another possibility is that in leaves treated with AA in which the pathway for SA is activated, SA is synthesized from pools of conjugated BA or CA in the vacuole or in the chloroplasts. The examination of samples after acid hydrolysis of the putative conjugates did not indicate the presence of large pools of conjugated CA or BA, but it should be noted that the estimation of both BA and CA by HPLC using UV or fluorescence detection is not very sensitive. This is in contrast to the data on tobacco leaves, in which pools of conjugated BA of about 100 μg g−1 fresh weight were observed (Yalpani et al., 1993).

The inhibition of PAL by AIP with a concomitant reduction in the amount of SA that accumulated in leaves after treatment with AA (Fig. 6B) confirmed that this step is limiting in the synthesis of SA. There was no evidence for a contribution to SA synthesis by a PAL-independent pathway, e.g. directly from chorismic acid or via anthranilic acid (data not shown). However, when CA or BA was added back to leaves treated with AIP and AA, only a partial recovery of SA levels was obtained (Fig. 6C) perhaps due to directing of CA to lignin biosynthesis or to the formation of conjugates sequestered in the vacuole. It may be argued that AIP is toxic and has an influence on the latter stages of SA synthesis, but this is thought unlikely, since similar concentrations of AIP had almost no effect on the synthesis of SA when BA was added back to cucumber leaves (Meuwly et al., 1995). Incomplete reversal of the AIP inhibition of PAL by CA or BA might also indicate that exogenous CA or BA do not efficiently reach the cells where the synthesis of SA occurs or that these metabolites are preferentially conjugated. This could also explain the decrease in the specific activity of SA observed after labeling with CA or BA. A possible alternative way to carry out the labeling experiments could involve using suspension-cultured cells. However, preliminary experiments showed that although the addition of AA to the culture medium did lead to changes, e.g. coloration of the cell walls, no increase in the amount of SA, either free or conjugated, was observed. In addition, a number of unidentified, fluorescent compounds were detected upon HPLC (not shown). These could represent putrescine and tyramine conjugates of hydroxycinnamic acids or 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde, since it was shown that such compounds are induced in suspension-cultured potato cells treated with an elicitor preparation from P. infestans (Keller et al., 1996).

In conclusion, the results presented here indicate that the pathway from Phe via CA and BA functions both in untreated leaves and leaves treated with AA, but that the size of the intermediate pools has a much bigger influence than originally thought. Analogous pools in cucumber were found to be much smaller and the turnover of the intermediates much faster such that they were not detected upon feeding labeled Phe (Meuwly et al., 1995). It should also be noted that healthy potato plants accumulate a considerable amount of conjugated SA (Coquoz et al., 1995) not found in the other healthy plants where SA biosynthesis occurs. The synthesis of SA induced by AA clearly involves PAL and is unlikely to take place via a PAL-independent pathway. Future studies will be directed at elucidating the rate-limiting steps of the biosynthesis of SA and examining more closely the pools of intermediates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to P. Meuwly and W. Mölders for helpful discussions and are indebted to H.-R. Hohl and G. Collet for providing the potato clone and the pathogen, respectively; to D.F. Klessig for supplying a sample of the SA conjugate; to N. Amrhein for supplying the AIP, and to L. Grainger and G. Rigoli for their excellent technical help.

Abbreviations:

- AA

arachidonic acid

- AIP

2-aminoindan-2-phosphonic acid

- BA

benzoic acid

- CA

cinnamic acid

- PAL

Phe ammonia-lyase

- SA

salicylic acid

- SAR

systemic acquired resistance

Footnotes

This work was partially supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant no. 31-34098.92).

LITERATURE CITED

- Barz W, Schlepphorst R, Wilhelm P, Kratzl K, Tengler E. Metabolism of benzoic acid and phenols in cell suspension cultures of soybean and mung bean. Z Naturforsch. 1978;33c:363–367. [Google Scholar]

- Chadha KC, Brown SA. Biosynthesis of phenolic acids in tomato plants infected with Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Can J Bot. 1974;52:2041–2046. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Y, Gisi U, Mösinger E. Systemic resistance of potato plants against Phytophthora infestans induced by unsaturated fatty acids. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1991;38:255–273. [Google Scholar]

- Coquoz JL, Buchala AJ, Meuwly Ph, Métraux JP. Arachidonic acid induces local but not systemic synthesis of salicylic acid and confers systemic resistance in potato plants to Phytophthora infestans and Alternaria solani. Phytopathol. 1995;85:1219–1224. [Google Scholar]

- Delaney TP, Uknes S, Vernooij B, Friedrich L, Weymann K, Negrotto D, Gaffney T, Gutrella M, Kessmann H. A central role of salicylic acid in plant disease resistance. Science. 1994;266:1247–1250. doi: 10.1126/science.266.5188.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards R. Conjugation and metabolism of salicylic acid in tobacco. J Plant Physiol. 1994;143:609–614. [Google Scholar]

- El-Basyouni S, Chen D, Ibrahim RK, Neish AC, Towers GHN. The biosynthesis of hydroxybenzoic acids in higher plants. Phytochemistry. 1964;3:485–492. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BE, Amrhein N. The “NIH-shift” during aromatic ortho-hydroxylation in higher plants. Phytochemistry. 1971;10:3069–3072. [Google Scholar]

- Enyedi AJ, Yalpani N, Silverman P, Raskin I. Localisation, conjugation and function of salicylic acid in tobacco during the hypersensitive reaction to tobacco mosaic virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2480–2484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney T, Friedrich L, Vernooij B, Negrotto D, Nye G, Uknes S, Ward E, Kessmann H, Ryals J. Requirement of salicylic acid for the induction of systemic acquired resistance. Science. 1993;261:754–756. doi: 10.1126/science.261.5122.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Achmatowicz O, Hennig J, Indulski J, Klessig DF. Synthesis and characterization of the salicylic acid β-d-glucopyranoside. Polish J Chem. 1993;67:1251–1254. [Google Scholar]

- Hennig J, Malamy J, Grynkiewicz G, Indulski J, Klessig D. Interconversion of the salicylic acid signal and its glucoside in tobacco. Plant J. 1993;4:593–600. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1993.04040593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller H, Hohlfeld H, Wray V, Hahlbrock K, Scheel D, Strack D. Changes in the accumulation of soluble and cell wall-bound phenolics in elicitor-treated suspension cultures and fungus-infected leaves of Solanum tuberosum. Phytochemistry. 1996;42:389–396. [Google Scholar]

- Klämbt HD. Conversion in plants of benzoic acid to salicylic acid and its β-d-glucoside. Nature. 1962;196:491. [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Léon J, Raskin I. Biosynthesis and metabolism of salicylic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4076–4079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Léon J, Yalpani N, Raskin I, Lawton MA. Induction of benzoic acid 2-hydroxylase in virus-inoculated tobacco. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:323–328. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.2.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine A, Tenhaken R, Dixon R, Lamb C. H2O2 from the oxidative burst orchestrates the plant hypersensitive disease resistance response. Cell. 1994;79:583–593. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90544-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamy J, Carr JP, Klessig DF, Raskin I. Salicylic acid: a likely endogenous signal in the resistance response of tobacco to viral infection. Science. 1990;250:1002–1004. doi: 10.1126/science.250.4983.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamy J, Klessig DF. Salicylic acid and plant disease resistance. Plant J. 1992;2:643–654. [Google Scholar]

- Métraux JP, Signer H, Ryals J, Ward E, Wyss-Benz M, Gaudin J, Raschdorf K, Schmid E, Blum W, Inverardi B. Increase in salicylic acid at the onset of systemic acquired resistance in cucumber. Science. 1990;250:1004–1006. doi: 10.1126/science.250.4983.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuwly P, Metraux JP. Ortho-anisic acid as internal standard for the simultaneous quantitation of salicylic acid and its putative biosynthetic precursors in cucumber leaves. Anal Biochem. 1993;214:500–505. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuwly P, Mölders W, Buchala A, Métraux JP. Local and systemic biosynthesis of salicylic acid in infected cucumber plants. Plant Physiol. 1995;109:1107–1114. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.3.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin I. The role of salicylic acid in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1992;43:439–463. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen JB, Hammerschmidt R, Zook MN. Systemic induction of salicylic acid accumulation in cucumber after inoculation with Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. Plant Physiol. 1991;97:1342–1347. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.4.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton JK, Ryals A, Delaney TP, Friedrich L, Kessmann H, Neuenschwander U, Uknes S, Vernooij B, Weymann K. Signal transduction in systemic acquired resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4202–4205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman P, Seskar M, Kanter D, Schweizer P, Métraux J-P, Raskin I. Salicylic acid in rice. Biosynthesis, conjugation, and possible role. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:633–639. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.2.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernooij B, Friedrich L, Morse A, Reist R, Kolditzjawhar R, Ward E, Uknes S, Kessmann H, Ryals J. Salicylic acid is not the translocated signal responsible for inducing systemic acquired resistance but is required in signal transduction. Plant Cell. 1994a;6:959–965. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.7.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernooij B, Uknes S, Ward E, Ryals J. Salicylic acid as a signal molecule in plant-pathogen interactions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994b;6:275–279. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward ER, Uknes SJ, Williams SC, Dincher SS, Wiederhold DL, Alexander DC, Ahl-Goy P, Métraux JP, Ryals JA. Coordinate gene activity in response to agents that induce systemic acquired resistance. Plant Cell. 1991;3:1085–1094. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.10.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalpani N, Leon J, Lawton MA, Raskin I. Pathway of salicylic acid biosynthesis in healthy and virus-inoculated tobacco. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:315–321. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.2.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu D, Liu Y, Fan B, Klessig DF, Chen Z. Is the high basal level of salicylic acid important for disease resistance in potato? Plant Physiol. 1997;115:343–349. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.2.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenk MHM, Müller G. Biosynthese von p-Hydroxybenzoesäure und anderer Benzoesäuren in höheren Pflanzen. Z Naturforsch. 1964;19B:398–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zon J, Amrhein, N (1992) Inhibitors of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase: 2-aminoindan-2-phosphonic acid and related compounds. Liebigs Ann Chem, pp 625–628