Abstract

Chromatin structure and dynamics that are influenced by epigenetic marks, such as histone modification and DNA methylation, play a crucial role in modulating gene transcription. To understand the relationship between histone modifications and regulatory elements in breast cancer cells, we compared our chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-Seq) histone modification patterns for histone H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K9/16ac, and H3K27me3 in MCF-7 cells with publicly available formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory elements (FAIRE)-chip signals in human chromosomes 8, 11, and 12, identified by a method called FAIRE. Active regulatory elements defined by FAIRE were highly associated with active histone modifications, like H3K4me3 and H3K9/16ac, especially near transcription start sites. The H3K9/16ac-enriched genes that overlapped with FAIRE signals (FAIRE-H3K9/14ac) were moderately correlated with gene expression levels. We also identified functional sequence motifs at H3K4me1-enriched FAIRE sites upstream of putative promoters, suggesting that regulatory elements could be associated with H3K4me1 to be regarded as distal regulatory elements. Our results might provide an insight into epigenetic regulatory mechanisms explaining the association of histone modifications with open chromatin structure in breast cancer cells.

Keywords: breast neoplasms, ChIP-Seq, epigenetic regulation, formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory elements (FAIRE), histone modification

Introduction

The epigenetic regulation by DNA methylation and post-translational modifications of histones without altering DNA sequences is tightly linked to the gene expression program in eukaryotic genomes. The N-terminal tails of histones are subject to various types of modifications, such as acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, glycosylation, and sumoylation [1]. Dynamic changes by histone-modifying enzymes affect the chromatin accessibility to transcriptional machinery and thus modulate gene activation or silencing in diverse biological processes, such as transcription, DNA repair, development and differentiation, and genome stability [2-4]. Moreover, nucleosome positioning can also be controlled by specific histone modifications, leading to alteration of cross-talk among chromatin structure, exon-intron architecture, and RNA polymerase II binding [5, 6]. Genomewide profiles of histone modifications with chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-Seq) have revealed the characteristic genomic distribution and the association of gene functions and activities in eukaryotic genomes [7-12]. ChIP-Seq is a popularly used method to find genomewide protein binding sites with a high resolution by chromatin-immunoprecipitation by massive DNA sequencing using high-throughput sequencing technology [11]. For example, trimethylated histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3), which is catalyzed by trithorax complex, as well as histone acetylation (e.g., H3K9/16ac) are usually enriched at promoter regions or transcription start sites (TSSs) with open chromatin structure and positively correlated with gene transcriptional activation level. H3K4me1 is also found to be enriched at enhancer-associated regions. These modifications recruit the transcriptional machinery at target sites. Trimethylation of H3K27, catalyzed by polycomb group protein complex 2 (PRC2), contributes to gene silencing by promoting chromatin condensation and chromatin stabilization and is likely to spread over larger regions around TSSs of silent genes. The signals of H3K9me3 are high in silent genes or repressed chromatin domains, such as heterochromatin. The comprehensive and comparative analysis of many histone modifications in the human genome demonstrates that the combination of several histone modifications shows a modular pattern and regulates transcriptional activation in a cooperative manner [13]. Interestingly, many loci of H3K27me3 are often colocalized with those of H3K4me3 around TSSs of lowly expressed genes in stem-like cells, many of which are positioned at developmental regulators, including transcription factors and signaling proteins [14]. This suggests that the formation of a bivalent chromatin domain can be a signature of epigenetic memory and that programmed gene expression during differentiation is dependent on chromatin modifications [14].

The interactions of variations in the genome, epigenome, and transcriptome with sensing of environmental stimuli can determine phenotypic plasticity. Traditionally, phenotypic variation has been explained primarily through genetic variation with sequence changes during evolution. However, epigenetic variations that are potentially sensitive to environmental inputs can alter transcriptional activity, which in turn contributes to diversity of complex traits [15]. Such observations have been demonstrated in human cancers and plant development, such as floral symmetry and vernalization response (reviewed in [15, 16]). For example, silencing of tumor suppressor genes, including p16, VHL, MLH1, APC, and E-cadherin, is associated with DNA hypermethylation in the gene promoters [17]. In relation to histone modifications, overexpression of EZH2, a histone H3K27 methyltransferase, has been observed and positively correlated with the progression of multiple malignancies, including prostate cancer, breast cancer, lymphoma, myeloma, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer, bladder cancer, and melanoma [18]. In addition, generalized loss of H4K16ac and H4K20me3 is found in lymphoma and colorectal cancer, leading to transcriptional silencing [16].

Organization of genomic DNA into higher-order chromatin structures is involved in transcriptional regulation in eukaryotes [19, 20]. In particular, cis-regulatory elements complexes located in open chromatin regions, depleted of nucleosomes, are activated by the recruitment of transcriptional machinery [19, 20]. Such active regulatory elements have been identified by formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory elements (FAIRE) technique, a simple high-throughput screening method to isolate and map active regulatory elements depleted of nucleosomes in eukaryotes, especially in clinical samples, by forming crosslinks between histones and DNA and subsequent utilization of hybridization of tiling microarrays or next-generation sequencing [21-23]. FAIRE was first demonstrated in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, where formaldehyde-crosslinked chromatin immediately upstream of genes was preferentially segregated into the aqueous phase in a manner that was strongly negatively correlated with nucleosome occupancy [21]. Results from both yeast and human samples showed that enrichment of regions upstream of genes was positively correlated with transcription of downstream genes [21-23].

Breast cancer is a heterogeneous and progressive disease, known as the most common cancer among women. For early diagnosis and prognosis, the development of tumor makers in breast cancer is important, but the markers for its early detection are rare [24, 25]. The most clinically useful tissue-based marker genes in breast cancer are steroid receptors, estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors, and HER-2 [24, 25]. The mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 are strong indicators of breast cancer development, but their mutation is not common [25]. Except for genetic variation-based diagnosis, a comprehensive understanding of the gene expression program as well as epigenetic mechanisms is definitely required for the development of diagnosis markers and epigenetic therapies. We recently reported epigenetic regulatory mechanisms of gene expression with 3 different histone modifications (H3K4me1, H3K4me3, and H3K9/14ac) in normal (MCF-10A) and breast cancer (MCF-7) cells [26]. In particular, we demonstrated the change of transcriptional activity, delineating differential enrichment of histone modifications in both MCF-10A and MCF-7, which defines the functional regulatory elements in the genome with a cell type-specific chromatin environment [26]. To address the relationships between histone modifications and FAIRE and between FAIRE-related chromatin structure and transcriptional activity, we analyzed FAIRE-chip [23], histone modification-ChIP-Seq [26], and gene expression microarrays derived from MCF-7. Our result provides an understanding of epigenetic regulatory mechanisms with open chromatin in breast cancer cells.

Methods

Subjects

The FAIRE-chip data, covering human chromosomes 8, 11, and 12, derived from MCF-7 cell lines, were downloaded from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (GSE11579) [23]. The ChIP-Seq data (SRA045635) of H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K9/14ac, and input DNA (mononucleosome digested with micrococcal nuclease) in MCF-7 were obtained from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) at the National Center for Biotechnical Information (NCBI) [26]. The H3K27me3 ChIP-Seq data were generated with Genome Analyzer IIx (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) according to the method described by Choe et al. [26]. The gene expression data using the Human Genome U133Plus 2.0 array platform (Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) were collected from the GEO database (GSM276046-GSM276048 for MCF-7) [27].

Peak identification and statistical analysis

The FAIRE-chip data were processed by using CisGenome [28] for normalization, signal detection, and identification of significant FAIRE regions. The 26-bp ChIP-Seq reads for H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K9/14ac, H3K27me3, and input DNA were aligned to a human reference sequence (hg18) using the CASABA 1.6 program (Illumina Inc.), and the resulting mapped tag counts were normalized for the comparative analysis. To identify peaks enriched with a specific histone modification, the Hypergeometric Optimization of Motif EnRichment (HOMER) package version 3.2 [29] was used with the following options: approximate fragment length, 150 bp; peak size, 150 bp; minimum distance between peaks, 370 bp (equivalent to peak size × 2.5); Poisson p-value threshold relative to local tag count, 0.0001; default false discovery rate threshold, 0.001; and center switch for centering peaks on maximum ChIP fragment overlap and calculating focus ratios. The FAIRE sites coinciding with histone-modified peaks were defined when the distance between the center positions of FAIRE sites and histone-modified peaks was shorter than 100 base pairs. The co-existing sites of FAIRE and histone modifications were plotted, centered at the genes' TSSs using seqMINER with k-mean clustering method [30]. Expression levels of genes associated with the FAIRE-histone-modified regions were examined, and gene ontology (GO) enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis were performed by using the DAVID Functional Annotation Tool [31]. In addition, functional, enriched motifs in FAIRE-histone-modified regions were also found by using MEME suite [32] and the TOMTOM motif database [33].

Results

Chromatin structure defined by FAIRE and histone modifications

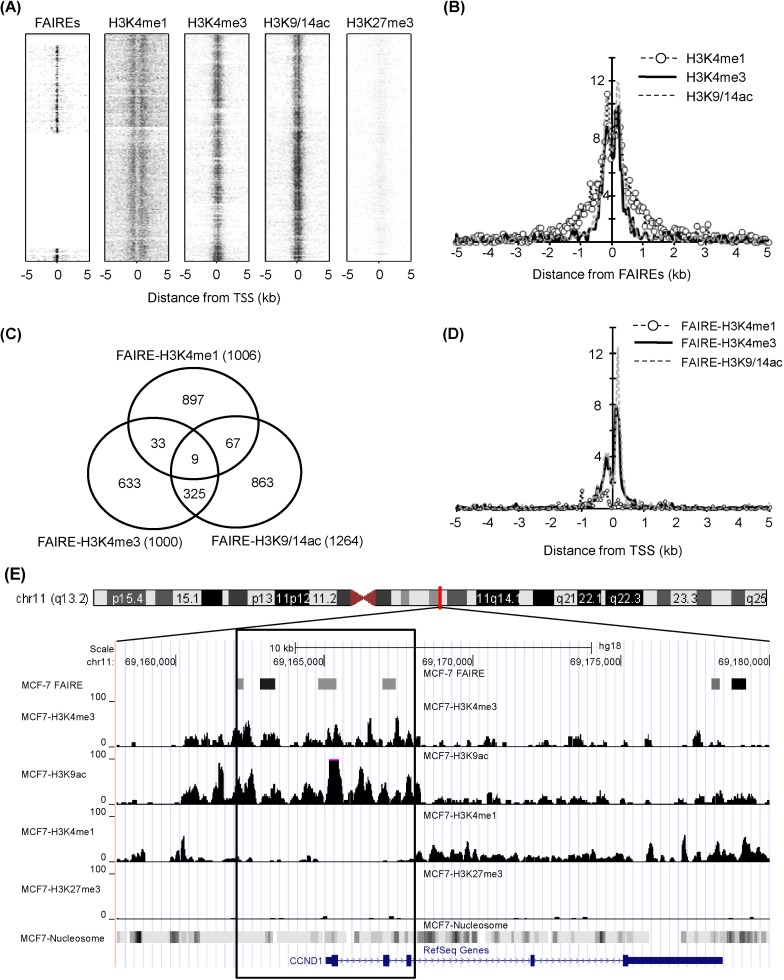

The chromatin structure was analyzed by comparing genomic regions defined by FAIRE with histone modification sites detected by ChIP-Seq in a breast cancer cell line, MCF-7. Due to the limited information of FAIRE-chip data, we analyzed regions enriched in human chromosomes 8, 11, and 12. The overall positions of regulatory elements and histone modifications relative to TSS are depicted in Fig. 1A. The k-clustered pattern, depending on their enrichment level, showed that most H3K4me3 and H3K9/14ac modifications, known as active chromatin marks, were enriched near TSS, whereas H3K27me3, a repressive mark, was not. Many regulatory elements detected by FAIRE-chip were also located near TSS, reflecting that promoters are one of the major nucleosome-free sites. The relative positions of 3 histone modification enrichments (H3K4me1, H3K4me3, and H3K9/14ac) were aligned to the center of FAIRE signals and overlapped within ± 1-kb regions from TSSs (Fig. 1B). The H3K4me1 had a broader spectrum than the other 2 modifications in ± 0.5-1.5-kb regions. These results implied that regulatory elements were highly correlated with active histone modifications and associated with open chromatin structure.

Fig. 1.

Chromatin structure in genomic regions defined by formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory elements (FAIRE) in MCF7. (A) Profile of FAIRE and histone modifications (H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K9/14ac, and H3K27me3) on a chromosome scale (chromosome 8, 11, and 12). The peaks denoted by spots were plotted by k-clustering using seqMiner program. (B) Histone modification peak profiles were analyzed, centered on FAIRE signals. The Y axis represents the normalized sum of peak counts, multiplied by 10,000. (C) The overlapping of each FAIRE-histone modification was estimated. (D) FAIRE-histone modifications ranging from -5 kb to 5 kb of transcription start sites (TSSs) were plotted. (E) Chromatin state at CCND1 locus. The box indicates ±3 kb region from TSS.

A total of 2,804 regulatory elements from FAIRE-chip data were identified by CisGenome analysis, and the number of ChIP-Seq peaks was calculated using HOMER program: 18,938 for HK4me1, 4,516 for H3K4me3, 5,763 for H3K9/14ac, and 3,324 for H3K27me3 (Table 1). The FAIRE sites were located in especially functional element-related regions: promoters (32.2% of FAIRE sites analyzed), 4 kb upstream of promoters (3.2%), gene bodies (39.1%), and intergenic regions (25.4%). In particular, the highest enrichment of FAIREs in promoters could be identified by the normalization in quantitative comparison of FAIRE profiles (i.e., the total number of peaks/total length of each of genomic feature). We selected the overlapping regulatory elements of FAIRE signals with ChIP-Seq peaks and looked at their co-occurrence; the regulatory elements with H3K4me1 (FAIRE-H3K4me1) were 1,006; FAIRE-H3K4me3, 1,000; and FAIRE-H3K9/14ac, 1,264. Among them, 334 elements showed enrichment of both H3K4me3 and H3K9/14ac (Fig. 1C). This relationship was further confirmed by the distribution of FAIRE-histone modifications, shown in Fig. 1D. The highest population of FAIRE-H3K4me3 and FAIRE-H3K9/14ac was observed immediately downstream of TSS (Fig. 1D). A weak enrichment of FAIRE-H3K4me1 elements was detected upstream of TSS, where a shoulder peak of FAIRE-H3K4me1 and H3K4me3 was positioned. For example, 4 FAIRE regulatory elements of cyclin D1 (CCND1), involved in tumorigenesis as a cell cycle regulator, were located at the promoter and overlapped with peaks of H3K4me3 and H3K9/14ac but not with H3K4me1 or H3K27me3 (Fig. 1E). Instead, the H3K4me1 peaks in the CCND1 gene locus were expanded along the gene body and far upstream of TSS.

Table 1.

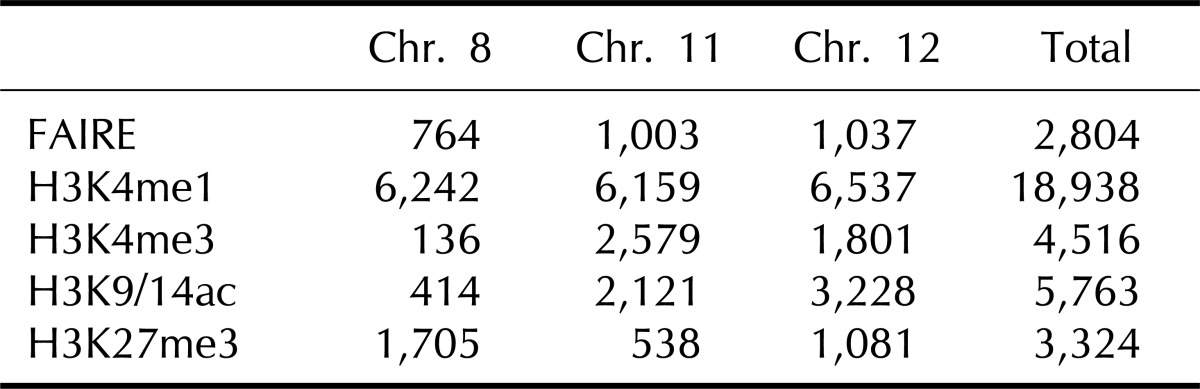

The number of peaks of formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory elements (FAIRE) and histone modifications analyzed in this study

Gene expression and FAIRE-histone modifications

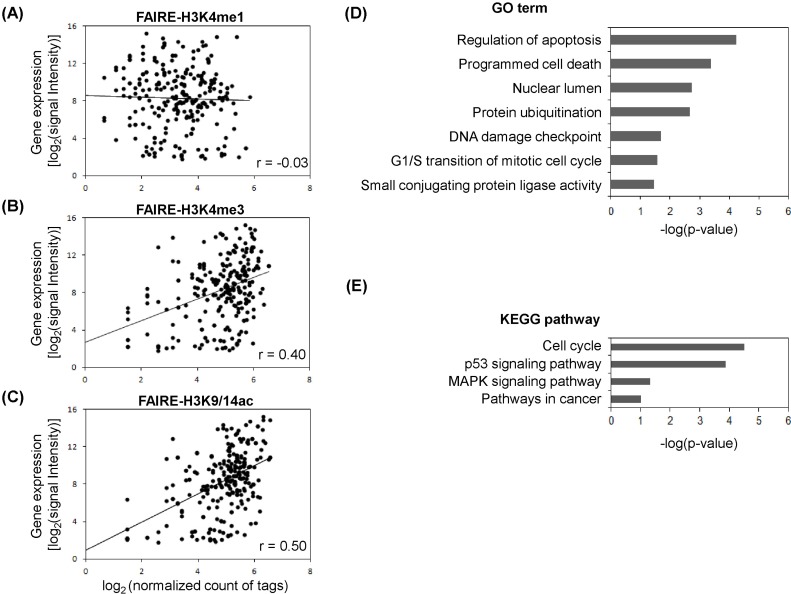

The gene expression program is tightly controlled by a dynamic chromatin environment, which epigenetic factors, like histone modifications and DNA methylation, play a crucial role in determining. As shown in Fig. 1, we found the linkage of FAIRE regulatory elements with histone modification profiles. To further assess the FAIRE-histone modifications, the gene expression profiles for MCF-7 cells were integrated (Fig. 2). From the overlapped regulatory elements determined by comparison of FARE-H3K4me1 (1,006), FAIRE-H3K4me3 (1,000), and FAIRE-H3K9/14ac (1,264), we selected 229 genes associated with at least 2 of 3 FAIRE-histone modification combinations. Scatter plots were produced to see how the expression level agreed with degree of histone modification (Fig. 2A-2C). The Pearson correlation coefficients between histone modifications and the expression level of genes with FAIRE elements were generally low. The highest coefficient was r = 0.50 for the pair of gene expression and FAIRE-H3K9/14ac (Fig. 2C), and the next was r = 0.4 for gene expression and FAIRE-H3K4me3 (Fig. 2B). However, FAIRE-H3K4me1 showed almost no correlation with gene expression level (r = -0.03) (Fig. 2A). To examine whether breast cancer-related genes were up-regulated in MCF-7 and appeared to have a high level of H3K9/14ac, as found in our previous study [26], we selected 68 genes, the expression levels of which ranked in the top 30% among FAIRE-H3K9/14ac-associated genes, and performed DAVID Functional Annotation analysis. We could isolate 29 functionally significant genes with p < 0.05: ATM, BTG1, CCND1, CDK4, CDKN1B, CRADD, CSDA, CTR9, DDB2, DUSP6, ERBB3, ESPL1, FADD, H2AFX, KRT18, KRT8, MADD, MDM2, MYC, NR4A1, POLA2, RIPK2, RRM2B, SART3, SMARCC2, TSG101, UBE2N, XPOT, and YWHAZ. These genes were associated with the following GO categories: regulation of apoptosis, programmed cell death, nuclear lumen, protein ubiquitination, DNA damage checkpoint, mitotic cell cycle, and small conjugating protein ligase activity (Fig. 2D). Moreover, the KEGG pathway analysis displayed their involvement in the cell cycle, p53 signaling pathway, mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway, and pathways in cancer (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

Formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory elements (FAIRE)-histone modifications and gene expression profile. (A) Gene expression level and histone modification enrichment. Inserts are Pearson correlation coefficients (r). (B) Gene expression level and histone H3K4me3 enrichment. (C) Gene expression level and histone H3K9/14ac enrichment. (D) Gene ontology (GO) analysis for top 30% ranked expressed genes in H3K9/14ac enrichment. (E) Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis for top 30% ranked expressed genes in H3K9/14ac enrichment. MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase.

Sequence motif analysis for FAIREs marked by active histone modifications

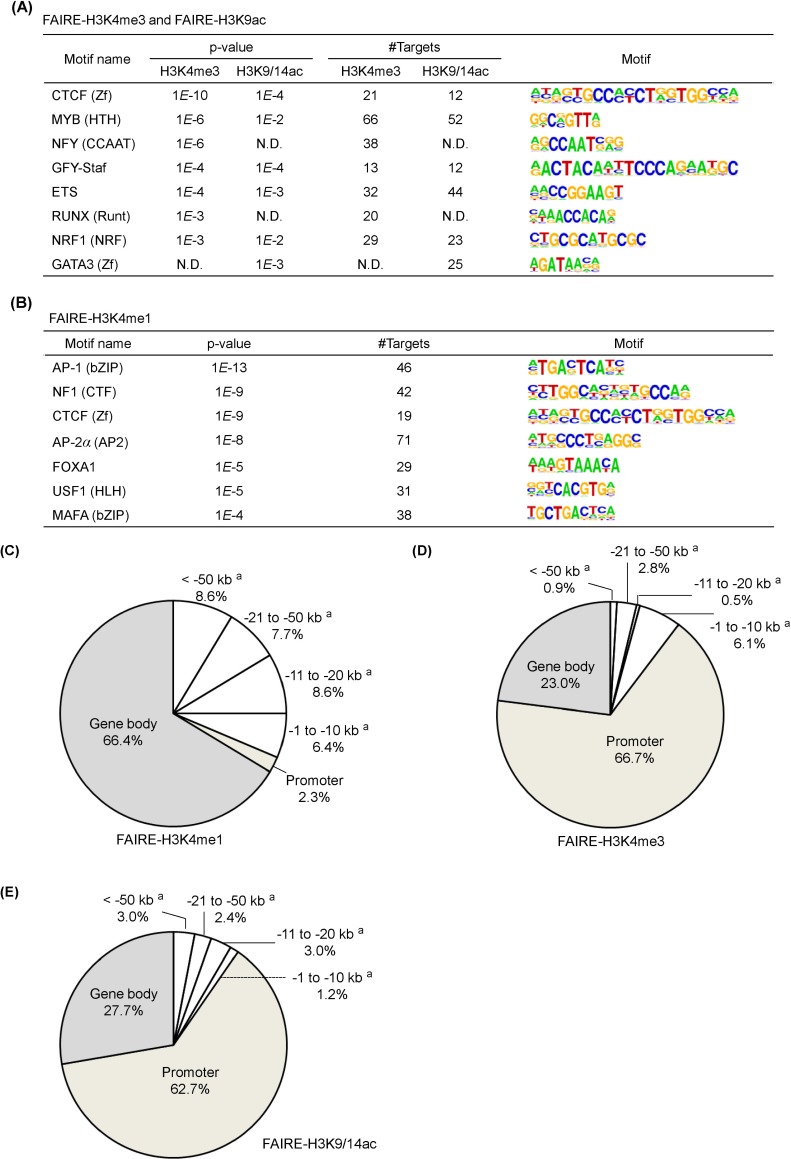

As many FAIRE regulatory elements were linked with active histone modifications, we explored the possible existence of functional sequence motifs for known transcription factors in FAIRE-H3K4me3 and FAIRE-H3K9/14ac sites. The binding motifs, such as CTCF, MYB, GFY-staf, ETS, and NRF1, were common in both FAIRE-H3K4me3 and FAIRE-H3K9/14ac sites (Fig. 3A). However, NFY and RUNX motifs existed only in FAIRE-H3K4me3 sites, and the GATA3 motif was specifically detected in FAIRE-H3K9/14ac sites. For FAIRE-H3K4me1 sites, AP-1/2, NF1, CTCF, AP-2, FOXA1, USF1, and MAFA motifs were identified (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, the CTCF motif was commonly found in FAIRE-H3K4me1, FAIRE-H3K4me3, and FAIRE-H3K9/14ac. The genomewide positioning of regulatory elements marked by histone modifications is illustrated in a Venn diagram (Fig. 3C-3E). More than 60% of the FAIRE-H3K4me3 and FAIRE-H3K9/14ac regions carrying binding motifs were distributed at gene promoters; over 20% in the gene body; and at small portions far upstream of promoters (Fig. 3D and 3E). In contrast, the population of FAIRE-H3K4me1 was highly enriched in gene body regions (66.4%) as well as upstream of promoters (31.3%) but almost negligible at promoters (2.3%) (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Motif analysis for formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory elements (FAIRE)-related genomic regions marked by H3K4me1, H3K4me3, and H3K9/14ac. (A) Motif analysis for FAIRE marked by H3K4me3 and H3K9/14ac. (B) Motif analysis for FAIRE marked by H3K4me1. (C) Genomic distribution of motifs identified from FAIRE-H3K4me1. (D) Genomic distribution of motifs identified from FAIRE-H3K4me3. (E) Genomic distribution of motifs identified from FAIRE-H3K9/14ac. N.D., not determined.

aUpstream regions from transcription start sites.

Discussion

FAIRE has been known to enrich functional DNAs located in DNase I hypersensitive sites, active promoters, and transcriptional start sites [22]. The enrichment of such regulatory regions in the aqueous phase might result in easy identification of genomic function without bias. Eeckhoute et al. [23] demonstrated that FOXA1-bound enhancers defined by FAIRE in human chromosomes 8, 11, and 12 were closely related with cell-type specific chromatin remodeling. In addition, it was reported that FAIREs are highly associated with DNase I hypersensitivity sites, RNA polymerase II, and TAF1 binding sites [22]. In combination with the information on these FAIRE regulatory elements in MCF-7 cells, we analyzed our genomewide histone modification data (H3K4me1, H3K4me3, and H3K9/14ac) generated by ChIP-Seq [26]. It was shown that the H3K4me1 distribution, covering the entire human genome, which was different from the pattern of H3K4me3 and H3K9/14ac, was 53% of the gene body, 42% of the intergenic region, and 5% of the promoter. The promoter regions covered 54% and 52% of total sequence reads in H3K4me3 and H3K9/14ac, respectively. The pair-wise colocalization analysis between 2 histone modifications gave poor correlation coefficients in the H3K4me1-H3K4me3 pair (r = 0.14) and H3K4me1-H3K9/14ac pair (r = 0.19) but good coincidence in the H3K4me3-H3K9/14ac pair (r = 0.86) when the Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated with normalized tag counts detected within 1 kb upstream and downstream of TSSs [26]. The co-occupancy of FAIRE elements with histone modifications is examined in Fig. 1, where it is clear that the promoters were the most abundant regulatory elements. Two active histone modifications, H3K4me3 and H3K9/14ac, were highly enriched within ± 1 kb from TSSs (Fig. 1A), and a comparative analysis showed that the FAIRE regulatory elements associated with histone modifications were positioned at promoters (Fig. 1D). Such epigenetic relationship between FAIRE and active histone modification marks has also been demonstrated in various cell types [22, 23, 34-36]. As exemplified in Fig. 1E, H3K4me1 was differentially positioned, and the distribution of FAIRE-H3K4me1 sites was away from promoter regions, meaning that FAIRE-H3K4me1 sites might be distal regulatory elements, such as enhancers [37].

The level of gene expression is also modulated, depending on the degree and position of various kinds of histone modifications. As shown in Fig. 2A-2C, genes with FAIRE sites carrying H3K4me3 and H3K9/14ac had relatively high expression levels compared to those with FAIRE-H3K4me1. Some genes related with breast cancer were up-regulated and showed high levels of H3K9/14ac in our previous study [26]. We therefore examined 68 genes with FAIRE-H3K9/14ac sites with the DAVID GO analysis tool. These genes were significantly related with cell cycle, apoptosis, DNA damage, and signaling pathways, reflecting that their in vivo functions are essential for cell survival and proliferation. Many of the regulatory sites associated with histone modifications contained transcription factor binding motifs (Fig. 3A and 3B). CTCF binding sites, commonly found in FAIRE-H3K4me1, FAIRE-H3K4me3, and FAIRE-H3K9/14ac, are related to a function of insulators and involved in high-order chromatin structure [38], and DNA demethylation is also known to be coincident with FAIRE-related open chromatin [36, 39]. Using computational motif analysis coupled with ChIP assay, Waki et al. [36] demonstrated that enrichment of a binding motif for nuclear family I (NFI) transcription factors was highly associated with adipocyte-specific FAIRE signals as well as active histone modifications, like H3K4me3 and H3K27ac, providing a global view of cell type-specific regulatory elements in the genome and an identification of transcriptional regulators of adipocyte differentiation [35]. Such selective activities of regulatory elements were also reported by monitoring the chromatin structure at FOXA1-bound enhancers defined by FAIRE [26]. This evidence supports the possibility that open chromatin structures are subject to be bound by many transcription factors and that histone modifications function as markers for these factors to be recruited.

In conclusion, our results suggest that genomic regions defined by FAIRE in breast cancer cells should be highly associated with active histone modifications, such as H3K4me1, H3K4me3, and H3K9/14ac, and play a crucial role in controlling gene expression programs. This analysis will provide an understanding of epigenetic regulatory mechanisms with open chromatin in breast cancer cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation (KRF-2008-313-C00665, 2010-0023412, and 2010-0026759) and the World Class University program, NRF, MEST (R31-10105), Republic of Korea.

References

- 1.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marmorstein R, Trievel RC. Histone modifying enzymes: structures, mechanisms, and specificities. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1789:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black JC, Whetstine JR. Chromatin landscape: methylation beyond transcription. Epigenetics. 2011;6:9–15. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.1.13331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou VW, Goren A, Bernstein BE. Charting histone modifications and the functional organization of mammalian genomes. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:7–18. doi: 10.1038/nrg2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schones DE, Cui K, Cuddapah S, Roh TY, Barski A, Wang Z, et al. Dynamic regulation of nucleosome positioning in the human genome. Cell. 2008;132:887–898. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwartz S, Meshorer E, Ast G. Chromatin organization marks exon-intron structure. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:990–995. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernstein BE, Humphrey EL, Erlich RL, Schneider R, Bouman P, Liu JS, et al. Methylation of histone H3 Lys 4 in coding regions of active genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8695–8700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082249499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roh TY, Ngau WC, Cui K, Landsman D, Zhao K. High-resolution genome-wide mapping of histone modifications. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1013–1016. doi: 10.1038/nbt990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roh TY, Cuddapah S, Zhao K. Active chromatin domains are defined by acetylation islands revealed by genome-wide mapping. Genes Dev. 2005;19:542–552. doi: 10.1101/gad.1272505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roh TY, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Zhao K. The genomic landscape of histone modifications in human T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15782–15787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607617103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, et al. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129:823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schones DE, Zhao K. Genome-wide approaches to studying chromatin modifications. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:179–191. doi: 10.1038/nrg2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z, Zang C, Rosenfeld JA, Schones DE, Barski A, Cuddapah S, et al. Combinatorial patterns of histone acetylations and methylations in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2008;40:897–903. doi: 10.1038/ng.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong CP, Park J, Roh TY. Epigenetic regulation in cell reprogramming revealed by genome-wide analysis. Epigenomics. 2011;3:73–81. doi: 10.2217/epi.10.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He G, Elling AA, Deng XW. The epigenome and plant development. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2011;62:411–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feinberg AP. Phenotypic plasticity and the epigenetics of human disease. Nature. 2007;447:433–440. doi: 10.1038/nature05919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrg816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang GG, Allis CD, Chi P. Chromatin remodeling and cancer, Part I: Covalent histone modifications. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:363–372. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozsolak F, Song JS, Liu XS, Fisher DE. High-throughput mapping of the chromatin structure of human promoters. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:244–248. doi: 10.1038/nbt1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinfeld I, Shamir R, Kupiec M. A genome-wide analysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae demonstrates the influence of chromatin modifiers on transcription. Nat Genet. 2007;39:303–309. doi: 10.1038/ng1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagy PL, Cleary ML, Brown PO, Lieb JD. Genomewide demarcation of RNA polymerase II transcription units revealed by physical fractionation of chromatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6364–6369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1131966100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giresi PG, Kim J, McDaniell RM, Iyer VR, Lieb JD. FAIRE (Formaldehyde-Assisted Isolation of Regulatory Elements) isolates active regulatory elements from human chromatin. Genome Res. 2007;17:877–885. doi: 10.1101/gr.5533506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eeckhoute J, Lupien M, Meyer CA, Verzi MP, Shivdasani RA, Liu XS, et al. Cell-type selective chromatin remodeling defines the active subset of FOXA1-bound enhancers. Genome Res. 2009;19:372–380. doi: 10.1101/gr.084582.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weigelt B, Peterse JL, van't Veer LJ. Breast cancer metastasis: markers and models. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:591–602. doi: 10.1038/nrc1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marić P, Ozretić P, Levanat S, Oresković S, Antunac K, Beketić-Oresković L. Tumor markers in breast cancer: evaluation of their clinical usefulness. Coll Antropol. 2011;35:241–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choe MK, Hong CP, Park J, Seo SH, Roh TY. Functional elements demarcated by histone modifications in breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;418:475–482. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stinson S, Lackner MR, Adai AT, Yu N, Kim HJ, O'Brien C, et al. TRPS1 targeting by miR-221/222 promotes the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra41. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ji H, Jiang H, Ma W, Johnson DS, Myers RM, Wong WH. An integrated software system for analyzing ChIP-chip and ChIP-seq data. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1293–1300. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell. 2010;38:576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ye T, Krebs AR, Choukrallah MA, Keime C, Plewniak F, Davidson I, et al. seqMINER: an integrated ChIP-seq data interpretation platform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e35. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, Frith M, Grant CE, Clementi L, et al. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gupta S, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Bailey TL, Noble WS. Quantifying similarity between motifs. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R24. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-2-r24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hogan GJ, Lee CK, Lieb JD. Cell cycle-specified fluctuation of nucleosome occupancy at gene promoters. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song L, Zhang Z, Grasfeder LL, Boyle AP, Giresi PG, Lee BK, et al. Open chromatin defined by DNaseI and FAIRE identifies regulatory elements that shape cell-type identity. Genome Res. 2011;21:1757–1767. doi: 10.1101/gr.121541.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waki H, Nakamura M, Yamauchi T, Wakabayashi K, Yu J, Hirose-Yotsuya L, et al. Global mapping of cell type-specific open chromatin by FAIRE-seq reveals the regulatory role of the NFI family in adipocyte differentiation. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tian Y, Jia Z, Wang J, Huang Z, Tang J, Zheng Y, et al. Global mapping of H3K4me1 and H3K4me3 reveals the chromatin state-based cell type-specific gene regulation in human Treg cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phillips JE, Corces VG. CTCF: master weaver of the genome. Cell. 2009;137:1194–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sérandour AA, Avner S, Percevault F, Demay F, Bizot M, Lucchetti-Miganeh C, et al. Epigenetic switch involved in activation of pioneer factor FOXA1-dependent enhancers. Genome Res. 2011;21:555–565. doi: 10.1101/gr.111534.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]