Abstract

CKIP-1 is an activator of the Smurf1 ubiquitin ligase acting to promote the ubiquitylation of Smad5 and MEKK2. The mechanisms involved in the recognition and degradation of these substrates by the proteasome remain unclear. Here, we show that CKIP-1, through its leucine zipper, interacts directly with the Rpt6 ATPase of the 19S regulatory particle of the proteasome. CKIP-1 mediates the Smurf1–Rpt6 interaction and delivers the ubiquitylated substrates to the proteasome. Depletion of CKIP-1 reduces the degradation of Smurf1 and its substrates by Rpt6. These findings reveal an unexpected adaptor role of CKIP-1 in coupling the ubiquitin ligase and the proteasome.

Keywords: proteasome, ubiquitin ligase, Smurf1, Rpt6, adaptor protein

INTRODUCTION

The process of ubiquitylation involves a ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) and a ubiquitin protein ligase (E3). E3 ligases specifically target substrate proteins for ubiquitylation, which are subsequently delivered to the 26S proteasome for degradation [1]. The 26S proteasome is composed of a 20S core particle (CP) and one or two 19S regulatory particles (RP). The 20S CP is formed by axial stacking of two outer α-rings and two inner β-rings. The 19S RP consists of at least 19 different subunits, which are divided into two subcomplexes: the base and the lid. The base bonds α-rings of CP and consists of six ATPases (Rpt1–Rpt6) and three non-ATPases (Rpn1, Rpn2 and Rpn13), and the lid is composed of nine non-ATPase subunits [2]. The 19S RP recognizes ubiquitylated substrates and deubiquitylates, unfolds and translocates them into the degradation chamber [2].

Smurf1 (Smad ubiquitylation regulatory factor 1) is a HECT-type E3 ligase and has important roles in diverse pathways by promoting the degradation of Smad1/5, MEKK2 and RhoA [3,4,5]. Previously, we discovered that the PH domain-containing protein CKIP-1 (casein kinase 2-interacting protein-1) acts as an activator of Smurf1 [6]. CKIP-1-deficient mice display high bone mass as a result of augmented bone formation. CKIP-1 enhances the binding between Smurf1 and its substrates [6]. Remarkably, in addition to promoting substrate degradation, CKIP-1 increases the autoubiquitylation and degradation of Smurf1 as well [6].

The recruitment of ubiquitylated proteins to the proteasome is fundamental in the degradation system. The ubiquitylated proteins are recognized by either the presence of intrinsic ubiquitin receptors in 19S RP (that is, Rpn10 and Rpn13) [7,8,9,10] or an extrinsic adaptor protein that bears both polyubiquitin-binding and proteasome-binding domains (Rad23, Dsk2 and Ddi1) [11,12,13,14]. All of these ubiquitin receptors recognize the targets through binding the ubiquitin chain, which represents a general mechanism of recognition. Intriguingly, there is evidence that the proteasome also recognizes the target protein itself rather than the ubiquitin chain, which represents a specific ‘VIP’ mechanism. For example, one ATPase subunit, Rpt5 (also known as TBP-1 or PSMC3), has been reported to bind to pVHL, a core component of a multi-subunit E3 ubiquitin ligase, to promote the degradation of HIF1α [15]. The ability of pVHL to degrade HIF1α depends, in part, on the interaction of pVHL with Rpt5. The delivery of ubiquitylated proteins to the 26S proteasome is a complex and sequential process [16], and it is unknown whether any other subunit of 19S RP recognizes the substrate through the ‘VIP’ mechanism exhibited by Rpt5.

Here, we provide evidence that Rpt6 (also known as PSMC5) interacts directly with CKIP-1 and promotes the turnover of Smurf1 and its substrates. This study establishes an adaptor role of CKIP-1 in coupling the E3 ligase Smurf1 and the 26S proteasome, and demonstrates another case of the ‘VIP’ mechanism of substrate recognition by a proteasome.

RESULTS

Rpt6 associates with CKIP-1

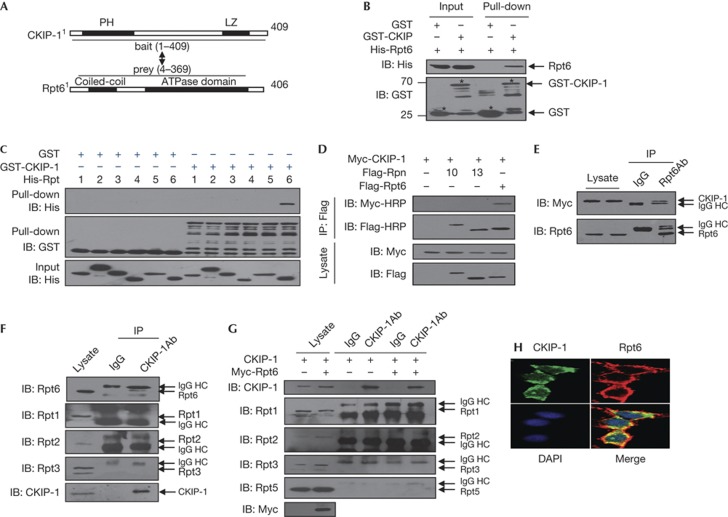

To investigate the mechanism by which Smurf1 is regulated by CKIP-1, we performed a yeast two-hybrid screen in the human adult brain library using CKIP-1 as bait. One of the potential interactors encodes nearly the entire Rpt6 (prey amino acids (aa) 4–369; full-length 406 aa), an ATPase of the RP of the 19S proteasome (Fig 1A). Interestingly, in an independent analysis to purify CKIP-1-associated proteins in RAW264.7 cells through immunoprecipitation (IP) followed by mass spectrometry, we identified a series of 26S proteasome subunits, including Rpt1, Rpt2, Rpt3 and Rpt6, as candidates (supplementary Table S1 online). These clues indicated that CKIP-1 might interact with the proteasome in addition to the E3 ligase (Smurf1).

Figure 1.

CKIP-1 interacts with Rpt6. (A) The ‘bait’ and ‘prey’ regions of CKIP-1 and Rpt6 in the yeast two-hybrid screening. (B) CKIP-1 and Rpt6 were produced in Escherichia coli and purified. Both input and GST pull-down samples were subjected to IB with anti-GST and anti-His antibodies. Input represented 10% of that used for pull-down. (C) GST-CKIP-1 and His-tagged Rpt subunits were produced, purified and used in the pull-down assays. (D) Co-IP assays of CKIP-1 with Rpt6, Rpn10 or Rpn13 in HEK293T cells. Myc-HRP antibody was used to prevent the interference of IgG HC. (E) Co-IP of endogenous Rpt6 and exogenous CKIP-1 in HEK293T cells. Whole-cell lysate and immunoprecipitate were analysed with anti-Rpt6 antibody or control IgG. IgG HC: heavy chain of IgG. (F) Co-IP of endogenous CKIP-1 and endogenous Rpt proteins in HEK293T cells. (G) HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag antibody or control IgG. The endogenous Rpt subunit proteins were detected. (H) Flag-Rpt6 and Myc-CKIP-1 were transfected into HEK293T cells and, 48 h later, stained with mouse anti-Flag and rabbit anti-Myc antibodies before visualization. CKIP-1, casein kinase 2-interacting protein-1; DAPI, 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; GST, glutathione S-transferase; IB, immunoblotting; IP, immunoprecipitation.

To validate the CKIP-1–Rpt6 association, an in vitro binding assay was performed. Glutathione S-transferase (GST)-fused CKIP-1, but not GST alone, was able to interact with Rpt6 (Fig 1B). Notably, CKIP-1 specifically interacted with Rpt6 but not other Rpt subunits (Fig 1C). In addition, no interaction was detectable between CKIP-1 and non-ATPase Rpn10 or Rpn13 (Fig 1D). Moreover, the ectopic CKIP-1 protein was detected in the immunoprecipitate of endogenous Rpt6 but not in that of IgG samples (Fig 1E). In addition, endogenous Rpt6 was detectable in the immunoprecipitate of endogenous CKIP-1, whereas other Rpt subunits were undetectable (Fig 1F). The overexpression of Rpt6 resulted in a slight increase in the interaction between endogenous CKIP-1 and Rpt1, and the interaction between CKIP-1 and Rpt2, Rpt3 or Rpt5 was still undetectable under these Co-IP conditions (Fig 1G). In HEK293T cells, Myc-Rpt6 and Flag-CKIP-1 proteins were mainly colocalized in the cytoplasm (Fig 1H). These results indicate that CKIP-1 specifically interacts with Rpt6 both in vitro and in cultured mammalian cells.

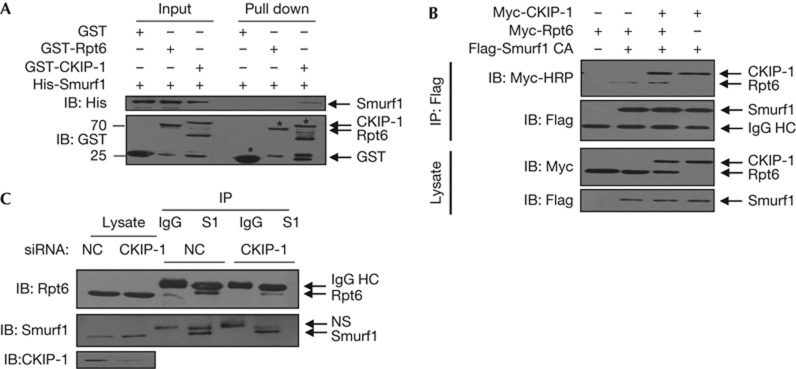

CKIP-1 couples Smurf1 and Rpt6 to form a complex

Given that CKIP-1 directly interacts with Smurf1 [6], we investigated whether Smurf1 is also associated with Rpt6. The in vitro binding assay showed that Smurf1 bound to CKIP-1 but not to Rpt6 (Fig 2A). However, we detected an interaction between Smurf1 and Rpt6 in HEK293T cells in both the exogenous (Fig 2B) and endogenous (Fig 2C) expression of Smurf1 and Rpt6. We hypothesized that the interaction between Smurf1 and Rpt6 might rely on CKIP-1. As expected, the depletion of CKIP-1 by RNA interference (RNAi) reduced the association of endogenous Smurf1 and Rpt6 (Fig 2C), whereas the overexpression of CKIP-1 moderately enhanced their interaction (Fig 2B).

Figure 2.

CKIP-1 couples Smurf1 and Rpt6 to form a complex. (A) GST pull-down assays with Smurf1 and Rpt6. The CKIP-1–Smurf1 interaction was used as the positive control. (B) HEK293T cells were transfected, and the lysates were incubated with anti-Flag to precipitate Smurf1. To prevent Smurf1 degradation, the ligase-defective C699A mutant was used. Myc-HRP antibody was used to prevent the interference of IgG HC. (C) The CKIP-1 siRNA was transfected into HEK293T cells and, 48 h later, treated with MG132 (10 μM) for 8 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Smurf1 antibody or control IgG. CKIP-1, casein kinase 2-interacting protein-1; GST, glutathione S-transferase; IB, immunoblotting; IP, immunoprecipitation; NS: nonspecificity; siRNA, short interfering RNA; Smurf1, Smad ubiquitylation regulatory factor 1.

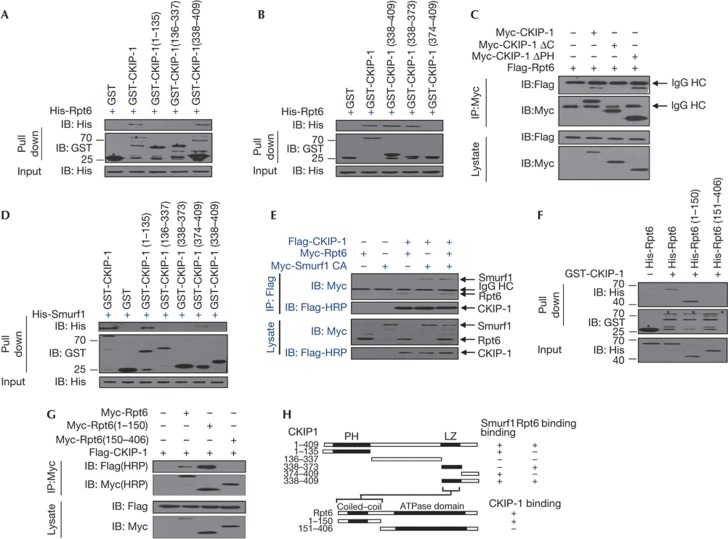

CKIP-1 LZ binds to the coiled–coil region of Rpt6

We next mapped the interaction region of CKIP-1 with Rpt6. The in vitro GST pull-down assay revealed that the leucine zipper (aa 338–373) of CKIP-1 mediated the interaction with Rpt6 (Fig 3A,B). Co-IP assays confirmed the critical role of the carboxy terminus of CKIP-1 (Fig 3C). By contrast, the amino-terminal PH domain (aa 1–135) and the extreme C terminus (aa 374–409) of CKIP-1, which are different from the CKIP-1–Rpt6-binding region, mediated the association with Smurf1 (Fig 3D). We previously showed that the mutant 1–337 could not interact with Smurf1 on the basis of Co-IP analysis in HEK293T cells [6]. This lack of interaction is likely caused by the mislocalization of 1–337 from the plasma membrane to the nucleus [17], preventing its access to Smurf1 despite the presence of the PH domain. Nonetheless, because of their different interaction regions, CKIP-1 could bind to Smurf1 and Rpt6 simultaneously (Fig 3E).

Figure 3.

Mapping of the interaction domains of CKIP-1 and Rpt6. (A,B) A series of CKIP-1 deletion mutants was examined for the ability to bind Rpt6 in GST pull-down assays. (C) Flag-Rpt6 and CKIP-1 or its deletion mutants were transfected into HEK293T cells, and Co-IP assays were performed with anti-Myc antibody. (D) GST pull-down assays with Smurf1 and various CKIP-1 mutants. (E) Flag-CKIP-1, Myc-Smurf1 and/or Myc-Rpt6 were transfected into HEK293T cells, and Co-IP assays were performed with the indicated antibodies. (F) A series of Rpt6 deletion mutants was assessed for the ability to interact with CKIP-1 in GST pull-down assays. (G) Flag-CKIP-1 and Rpt6 deletion mutants were transfected into HEK293T cells, and Co-IP assays were performed with anti-Myc antibody. (H) A schematic representation of the binding regions for interactions of CKIP-1–Rpt6 and CKIP-1–Smurf1. CKIP-1, casein kinase 2-interacting protein-1; GST, glutathione S-transferase; IB, immunoblotting; IP, immunoprecipitation; Smurf1, Smad ubiquitylation regulatory factor 1.

GST pull-down assays (Fig 3F) and Co-IP assays (Fig 3G) with Rpt6 deletion mutants revealed that the 1–150 region of Rpt6, harbouring the coiled–coil domain (but not the ATPase domain), was required for interaction with CKIP-1. Thus, the leucine zipper of CKIP-1 interacts with the coiled–coil region of Rpt6, and CKIP-1 utilizes different regions to bind to Rpt6 than to Smurf1 (Fig 3H).

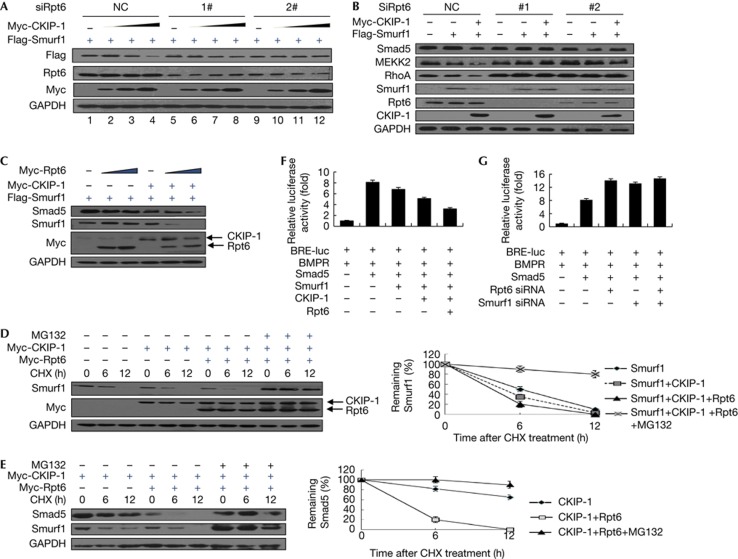

Rpt6 and CKIP-1 coordinate the substrate degradation

The fact that Rpt6 is an ATPase subunit of proteasome prompted us to examine whether Rpt6 is involved in the turnover of Smurf1 and its substrates. Consistent with our previous observation, CKIP-1 overexpression resulted in the degradation of Smurf1 (Fig 4A). The depletion of Rpt6 abolished this effect of CKIP-1 (Fig 4A). Similarly, CKIP-1 expression promoted the degradation of Smurf1 substrates, including Smad5, MEKK2 and RhoA, and Rpt6 depletion abolished these effects (Fig 4B). Conversely, Rpt6 overexpression enhanced the degradation of Smurf1 and its substrates when CKIP-1 was co-expressed (Fig 4C). Moreover, the half-life of Smurf1 was dramatically reduced after the co-expression of Rpt6 and CKIP-1, the effects of which were blocked by the treatment with proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Fig 4D). Similar effects were observed with the half-life of Smad5 (Fig 4E). Rpt6 expression did not influence the Smurf1 ubiquitylation (supplementary Fig S1 online), suggesting that the regulation of Smurf1 by Rpt6 was accomplished through the recruitment of Smurf1 to the proteasome.

Figure 4.

Rpt6 cooperates with CKIP-1 to promote the turnover of Smurf1 and its substrates. (A) HEK293T cells (12-well plate) were transfected with Flag-Smurf1 (0.2 μg), Myc-CKIP-1 (0.2, 0.4 and 0.8 μg) and two independent siRNAs against Rpt6 or non-targeting control siRNAs as indicated. Cell lysates were analysed by immunoblotting. (B) HEK293T cells were transfected with Flag-Smurf1, Myc-CKIP-1 and Rpt6 siRNAs as indicated. Cells were harvested to detect the expression of endogenous Smad5, MEKK2 and RhoA. (C) The indicated plasmids of Smurf1 (0.2 μg), CKIP-1 (0.3 μg) and Rpt6 (0.2, 0.4 μg) were cotransfected into HEK293T cells (12-well plate), and their protein levels were analysed by immunoblotting. (D) HEK293T cells were transfected with CKIP-1 and/or Rpt6. Thirty-six hours after transfection, cells were treated with cycloheximide (100 μg/ml) for 6 or 12 h, together with MG132 (10 μM). Cells were harvested for immunoblotting. The quantification of the Smurf1 half-life was performed and each point and is represented as the mean±s.d. of triplicate experiments. (E) HEK293T cells were transfected with CKIP-1 and/or Rpt6 and treated as in (D). The half-life of Smad5 was analysed and is shown. Each point represents the mean±s.d. of triplicate experiments. (F) The reporter activities of BRE-luc in HEK293T cells transfected with the indicated plasmids were measured. The consistently active mutant of BMP Receptor II (ca-BMPR) was transfected together. Data are presented as mean±s.d. (n=3). (G) HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated BMP receptor and the siRNAs against Rpt6 or Smurf1, and the reporter activities of BRE-luc were measured. Data are presented as mean±s.d. (n=3). CKIP-1, casein kinase 2-interacting protein-1; GADPH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; siRNA, short interfering RNA; Smurf1, Smad ubiquitylation regulatory factor 1.

Smad5 has a critical role in initiating gene expression during osteoblast differentiation; thus, Smurf1-mediated degradation of Smad5 inhibits bone formation. We tested whether Rpt6 had any effect on the Smad5-driven luciferase activity. As shown in Fig 4F, overexpression of BMP receptor and Smad5 led to a marked increase in BRE-Luc activity; Smurf1, together with CKIP-1, inhibited this reporter activity. The further ectopic expression of Rpt6 significantly strengthened this inhibitory effect. Consistent with this observation, depletion of endogenous Rpt6 by RNAi resulted in the increase of BRE-Luc activity (Fig 4G). To explore whether the effect of Rpt6 on BRE-Luc was in part through regulation of Smurf1, we performed Smurf1/Rpt6 double depletion. We found that the double depletion had a similar effect to the single depletion of either Rpt6 or Smurf1 (Fig 4G), suggesting that Rpt6 and Smurf1 regulated BMP signalling through the same mechanism.

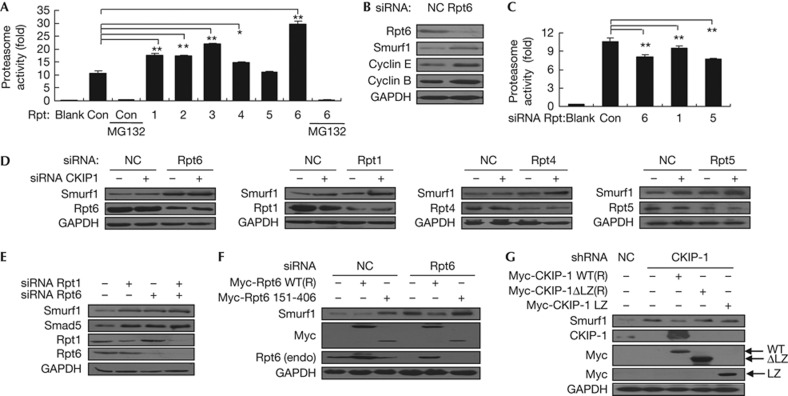

Next, we examined whether Rpt6 overexpression has any effect on the proteasome activity. An in vitro proteasome activity assay in which the cell lysate expressed ectopic Rpt6 or other Rpt subunits clearly showed that Rpt6 expression led to a threefold increase in proteasome activity, whereas the expression of other Rpt subunits caused moderate or weak effects (Fig 5A). This result suggests that in addition to the component of the intact proteasome, free Rpt6 also has a regulatory role on the assembly and activation of the proteasome. The depletion of endogenous Rpt6 resulted in the elevation of Smurf1, Cyclin E and Cyclin B levels (Fig 5B). This effect should be caused by the partial loss of the proteasome activity (Fig 5C). Notably, the depletion of one Rpt subunit had a moderate but not mortal effect on the proteasome activity, indicating that other subunits might compensate for the decreased expression of a single subunit.

Figure 5.

The proteasome-mediated degradation of Smurf1 via Rpt6 and CKIP-1. (A) HEK293T cells transfected with Rpt were harvested, and the proteasome activity was measured. Blank: the no-cell control. Con: the non-transfected control cell. *P<0.05; **P<0.01. (B) HEK293T cells were transfected with siRNAs as indicated. The expression of Smurf1, cyclin E and cyclin B was analysed. (C) HEK293T cells were transfected with siRNAs against Rpt, and the proteasome activity was detected. (D) HEK293T cells were transfected with CKIP-1 siRNA and/or the indicated Rpt siRNA, and the Smurf1 expression was analysed. (E) HEK293T cells were transfected with Rpt1 siRNA and/or Rpt6 siRNA, and the Smurf1 and Smad5 levels were measured. (F) HEK293T cells were transfected with Rpt6 siRNA and further the siRNA-resistant Rpt6 or its mutant. After 48 h, the cells were harvested, and endogenous Smurf1 was analysed. (G) HEK293T cells were transfected with CKIP-1 shRNA and further the resistant CKIP-1 plasmids. After 48 h, the cells were harvested, and endogenous Smurf1 was analysed. CKIP-1, casein kinase 2-interacting protein-1; GADPH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; siRNA, short interfering RNA; Smurf1, Smad ubiquitylation regulatory factor 1.

To further examine the association between CKIP-1 and Rpt6, we performed double-knockdown assays. The single knockdown of CKIP-1 or one Rpt protein resulted in a moderate increase in Smurf1 levels. The simultaneous knockdown of Rpt1, Rpt4 or Rpt5 together with CKIP-1 further elevated Smurf1 levels. By contrast, the knockdown of Rpt6 had no such effect, indicating that Rpt6 and CKIP-1 cooperated to promote Smurf1degradation. In addition, the double depletion of Rpt1 and Rpt6 had no further effects on Smurf1 upregulation (Fig 5E), which might stem from the fact that Rpt1 and Rpt6 regulate Smurf1 through the same 26S proteasome mechanism.

Finally, we performed rescue assays to confirm the functional relationship between CKIP-1 and Rpt6. The depletion of Rpt6 resulted in an increase of Smurf1 amount, and the re-introduction of wild-type Rpt6 promoted the degradation of Smurf1. By contrast, the re-introduction of the Rpt6 151–406 mutant, which lacks the coiled–coil region, had no such degradation effect. By contrast, this mutant somehow displayed an increasing effect (Fig 5F). Moreover, the re-introduction of wild-type CKIP-1 into the CKIP-1-depleted cells resulted in the decrease of Smurf1 levels. By contrast, this effect was not detectable with the CKIP-1 ΔLZ mutant, which lacks the Rpt6-binding leucine zipper (Fig 5G). The re-introduction of the CKIP-1 leucine zipper (338–373), which cannot bind to Smurf1, also had no effect on Smurf1 levels (Fig 5G). These data suggest that the interaction between CKIP-1 and Rpt6 is required for the regulation of Smurf1 turnover.

DISCUSSION

How the polyubiquitylated proteins are targeted to the proteasome is an essential and long-term topic. Rpn10 and Rpn13 were demonstrated as the intrinsic ubiquitin receptor of proteasome that recognize the ubiquitin chain of ubiquitylated proteins [7,8,9,10]. Rad23, Dsk2 and Ddi1 were identified as the extrinsic ubiquitin receptors for the proteasome [11,12,13,14]. In this study, we provide evidence that CKIP-1 couples the Smurf1 ubiquitin ligase (and its substrates) with the Rpt6 subunit of the proteasome, thereby establishing a direct linkage between the ubiquitylation and the degradation machinery. CKIP-1 utilizes the C-terminal leucine zipper (338–373) to interact with the Rpt6 coiled–coil region (1–150) and the extreme C terminus (374–409) plus the N-terminal PH domain (1–135) to interact with Smurf1, respectively (Fig 3). In the in vitro binding assay, Smurf1 was unable to bind to Rpt6. Depletion of CKIP-1 in cells significantly attenuates the interaction between Smurf1 and Rpt6. Overexpression of full-length Rpt6, but not the mutant lacking the CKIP-1-binding coiled–coil, promoted the degradation of Smurf1 in the presence of CKIP-1 (Figs 4C and 5F). Overexpression of Rpt6 had the most significant upregulation effect on the proteasome activity among Rpt subunits (Fig 5A). We propose a model in which CKIP-1 functions as both an auxiliary factor of Smurf1 to enhance its interaction with the substrate [6, 18] and an adaptor coupling Smurf1 with Rpt6 to promote the degradation of Smurf1 and its substrates (this study). Thus, the HECT-type E3 ligase and its substrates can be recruited to proteasome through the ligase cofactor. These findings provide new insight into the recognition mechanism used by the proteasome.

Notably, re-introduction of CKIP-1 ΔLZ mutant that is lack of the Rpt6-binding ability, or re-introduction of CKIP-1 LZ alone that cannot bind to Smurf1, into the CKIP-1-depleted cells could not rescue the effect of full-length CKIP-1 (Fig 5G). These data suggest that both the interaction between CKIP-1 and Rpt6, and the interaction between CKIP-1 and Smurf1, were required for CKIP-1 to promote Smurf1 turnover. Thus, both mechanisms (by inducing Smurf1–substrate interaction or by recruiting them to the 26S proteasome via Rpt6 subunit) are bona fide and critical for CKIP-1 function.

As Rpt6 was well defined as a component of the entire proteasome, one might speculate a simple mechanism for Rpt6 in Smurf1 degradation, that is, it acts in its established location incorporated into the ATPase ring of the proteasome cap. There it serves as a docking site for CKIP-1, allowing the latter to act as a substrate adaptor for the proteasome. If this simplest mechanism is the case, excess free Rpt6 (not incorporated into the proteasome) would compete CKIP-1 away from the proteasome and therefore inhibit Smurf1 degradation. However, based on our observations, we proposed that Rpt6 likely interacted with CKIP-1 in vivo mainly in its free isoform and second as part of an intact proteasome. This conclusion was based on the following evidences. First, in vitro binding assays showed that CKIP-1 uniquely recognized Rpt6 but not Rpt1-5 (Fig 1C). Second, Co-IP assays showed that the interaction between endogenous Rpt6 and endogenous CKIP-1 was detectable whereas the interaction between Rpt1, Rpt2 or Rpt3 with CKIP-1 was undetectable (Fig 1F). Even in the presence of ectopic Rpt6, the interaction between CKIP-1 and Rpt1, Rpt2, Rpt3 and Rpt5 was either very weak (for Rpt1) or undetectable (for Rpt2, Rpt3 and Rpt5) (Fig 1G). Third, an in vitro proteasome activity assay in which the cell lysate expressed ectopic Rpt6 or other Rpt subunits clearly showed that Rpt6 expression led to a threefold increase in proteasome activity, whereas the expression of other Rpt subunits caused moderate or weak effects (Fig 5A). This result suggests that in addition to the component of the intact proteasome, free Rpt6 also has a regulatory role on the assembly and activation of the proteasome. Therefore, we proposed that CKIP-1 interacted with free Rpt6 and enhanced the activity of Rpt6 to elevate the whole activity of 26S proteasome. Future studies should investigate the underlying mechanism by which Rpt6 regulates the entire proteasome activity. For example, could Rpt6 overexpression affect assembly of incomplete assembly intermediates or affect gene expression of proteasome subunits in some way?

Furthermore, CKIP-1 functions as a critical suppressor of bone formation [6], and the knockdown of CKIP-1 by short interfering RNA (siRNA) markedly enhances the bone micro-architecture and increases the bone mass in osteoporotic rats [19], suggesting that CKIP-1 might be a potential therapeutic target for osteoporosis. Thus, in addition to RNAi, either the CKIP-1–Smurf1 interaction or the CKIP-1–Rpt6 interaction might be promising targets for the design of drugs for osteoporosis therapy.

METHODS

Antibodies and reagents. Anti-Myc antibody was purchased from BD Biosciences. Anti-Flag M2, anti-Myc HRP and anti-Flag HRP antibodies; the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide; and the proteasome inhibitor MG132 were from Sigma. The Rpt6, Rpt1, Rpt2, Rpt3 and Rpt5 antibodies were from ENZO. Antibodies against Smurf1, Smad5 and RhoA were from Abcam. Anti-His and anti-GST antibodies were from Tiangen Biotech. Anti-MEKK2, anti-GAPDH and secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz.

Plasmids and transfection. Plasmids of human Rpt6, CKIP-1 and Smurf1, including deletions and other plasmids of Rpt1–Rpt5, Rpn10 and Rpn13, were constructed by PCR, followed by subcloning into various vectors. The lentiviral expression vector for CKIP-1 was constructed by inserting full-length complementary DNA into pWpt vector. Mammalian cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Infective lentiviruses were produced by cotransfection of expression vector and packaging plasmids into 293FT cells, which were added to HEK293T cells in the presence of 8 μg/ml polybrene.

IP, immunoblotting and GST pull-down assays. The IP, immunoblotting and GST pull-down assays were performed as previously described [20].

RNA interference. The siRNA against Rpt6 (1#: 5′-AAGGUACAUCCUGAAGGUAAATT-3′; 2#: 5′-GCAUUGACAGAAAAAUUGATT-3′), Rpt1 (5′-GCCAGGUGUACAAAGAUAATT-3′), Rpt4 (5′-UGGGUUGUCGUCGACAGCUUGACAA-3′), Rpt5 (5′-GGAUGAGGCCGAGCAAGAUGGAAUU-3′), CKIP-1 (5′-GGACUUGGUAGCAAGGAAATT-3′) [19], Smurf1 (5′-GCAUCGAAGUGUCCAGAGAAG-3′) and non-targeting siRNAs (5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGU-3′) were synthesized by Shanghai GenePharm. All siRNA transfections were performed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen).

Proteasome activity analysis. The proteasome chymotrypsin-like activity was assayed using the peptide substrate of Suc-LLVY-aminoluciferin, according to the manufacture’s instructions for the Proteasome-Glo cell-based assay kit (Promega). Briefly, 100 μl of Proteasome-Glo reagent was added to each 100 μl of cell sample, mixed and incubated for 10 min, and the luminescence was measured in an illuminometer.

Statistical analysis. Statistical evaluation was conducted using Student’s t-test. All experiments have been done at least three times independently.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the National Basic Research Programs (2012CB910304 and 2011CB910602) and National Natural Science Foundation Projects (31125010, 30830029, 30970601 and 31000338).

Author contributions: The project was conceived by Lingqiang Z. and F.H. The experiments were designed by Yifang W., J.N. and Lingqiang Z. The experiments were performed by Yifang W., J.N., Yiwu W., Luo Z, K.L., G.X. and P.X. The data were analysed by Yifang W., J.N., F.H. and Lingqiang Z. The manuscript was written by Yifang W., J.N. and Lingqiang Z.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Pickart CM (2001) Mechanisms underlying ubiquitylation. Annu Rev Biochem 70: 503–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata S, Yashiroda H, Tanaka K (2009) Molecular mechanisms of proteasome assembly. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10: 104–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Kavsak P, Abdollah S, Wrana JL, Thomsen GH (1999) A SMAD ubiquitin ligase targets the BMP pathway and affects embryonic pattern formation. Nature 400: 687–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita M, Ying SX, Zhang GM, Li C, Cheng SY, Deng CX, Zhang YE (2005) Ubiquitin ligase Smurf1 controls osteoblast activity and bone homeostasis by targeting MEKK2 for degradation. Cell 121: 101–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HR, Zhang Y, Ozdamar B, Ogunjimi AA, Alexandrova E, Thomsen GH, Wrana JL (2003) Regulation of cell polarity and protrusion formation by targeting RhoA for degradation. Science 302: 1775–1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K, Yin X, Weng T, Xi S, Li L, Xing G, Cheng X, Yang X, Zhang L, He F (2008) Targeting WW domains linker of HECT-type ubiquitin ligase Smurf1 for activation by CKIP-1. Nat Cell Biol 10: 994–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveraux Q, Ustrell V, Pickart C, Rechsteiner M (1994) A 26S protease subunit that binds ubiquitin conjugates. J Biol Chem 269: 7059–7061 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isasa M, Katz EJ, Kim W, Yugo V, González S, Kirkpatrick DS, Thomson TM, Finley D, Gygi SP, Crosas B (2010) Monoubiquitination of Rpn10 regulates substrate recruitment to the proteasome. Mol Cell 38: 733–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husnjak K, Elsasser S, Zhang N, Chen X, Randles L, Shi Y, Hofmann K, Walters KJ, Finley D, Dikic I (2008) Proteasome subunit Rpn13 is a novel ubiquitin receptor. Nature 453: 481–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner P, Chen X, Husnjak K, Randles L, Zhang N, Elsasser S, Finley D, Dikic I, Walters KJ, Groll M (2008) Ubiquitin docking at the proteasome through a novel pleckstrin-homology domain interaction. Nature 453: 548–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I, Mi K, Rao H (2004) Multiple interactions of rad23 suggest a mechanism for ubiquitylated substrate delivery important in proteolysis. Mol Biol Cell 15: 3357–3365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsasser S, Finley D (2005) Delivery of ubiquitinated substrates to protein-undolding machines. Nat Cell Biol 7: 742–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Vossler RA, Diaz-Martinez LA, Winter NS, Clarke DJ, Walters KJ (2006) UBL/UBA ubiquitin receptor proteins bind a common tetraubiquitin chain. J Mol Biol 356: 1027–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander GC, Estrin E, Matyskiela ME, Bashore C, Nogales E, Martin A (2012) Complete subunit architecture of the proteasome regulatory particle. Nature 482: 186–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corn PG, McDonald ER III, Herman JG, El-Deiry WS (2003) Tat-binding protein-1, a component of the 26S proteasome, contributes to the E3 ubiquitin ligase function of the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Nat Genet 35: 229–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peth A, Uchiki T, Goldberg AL (2010) ATP-dependent steps in the binding of ubiquitin conjugates to the 26S proteasome that commit to degradation. Mol Cell 40: 671–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi S et al. (2010) N-terminal PH domain and C-terminal auto-inhibitory region of CKIP-1 coordinate to determine its nucleus-plasma membrane shuttling. FEBS Lett 584: 1223–1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan L et al. (2011) Cdh1 regulates osteoblast function through an APC/C-independent modulation of Smurf1. Mol Cell 44: 721–733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G et al. (2012) A delivery system targeting bone formation surfaces to facilitate RNAi-based anabolic therapy. Nat Med 18: 307–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie J, Xie P, Liu L, Xing G, Chang Z, Yin Y, Tian C, He F, Zhang L (2010) Smad ubiquitylation regulatory factor 1/2 (Smurf1/2) promotes p53 degradation by stabilizing the E3ligase MDM2. J Biol Chem 285: 22818–22830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.