Abstract

Oseltamivir phosphonic acid (tamiphosphor, 3a), its monoethyl ester (3c), guanidino-tamiphosphor (4a) and its monoethyl ester (4c) are potent inhibitors of influenza neuraminidases. They inhibit the replication of influenza viruses, including the oseltamivir-resistant H275Y strain, at low nM to pM levels, and significantly protect mice from infection with lethal doses of influenza viruses when orally administered with 1 mg/kg or higher doses. These compounds are stable in simulated gastric fluid, liver microsomes and human blood, and are largely free from binding to plasma proteins. Pharmacokinetic properties of these inhibitors are thoroughly studied in dogs, rats and mice. The absolute oral bioavailability of these compounds was lower than 12%. No conversion of monoester 4c to phosphonic acid 4a was observed in rats after intravenous administration, but partial conversion of 4c was observed with oral administration. Advanced formulation may be investigated to develop these new anti-influenza agents for better therapeutic use.

INTRODUCTION

Influenza viruses infect humans every year through seasonal and pandemic infections due to the appearance of new influenza strains. For the prevention and treatment of influenza infections, vaccines and anti-influenza drugs are available. Though vaccines have been important for the protection of seasonal and pandemic influenza infections, the production needs to be started months before the onset of influenza infection. Furthermore, accurate prediction of the incoming influenza strains remains a major challenge. In the absence of an effective vaccine or for the treatment of influenza infections in unprotected individuals, anti-influenza drugs are needed.

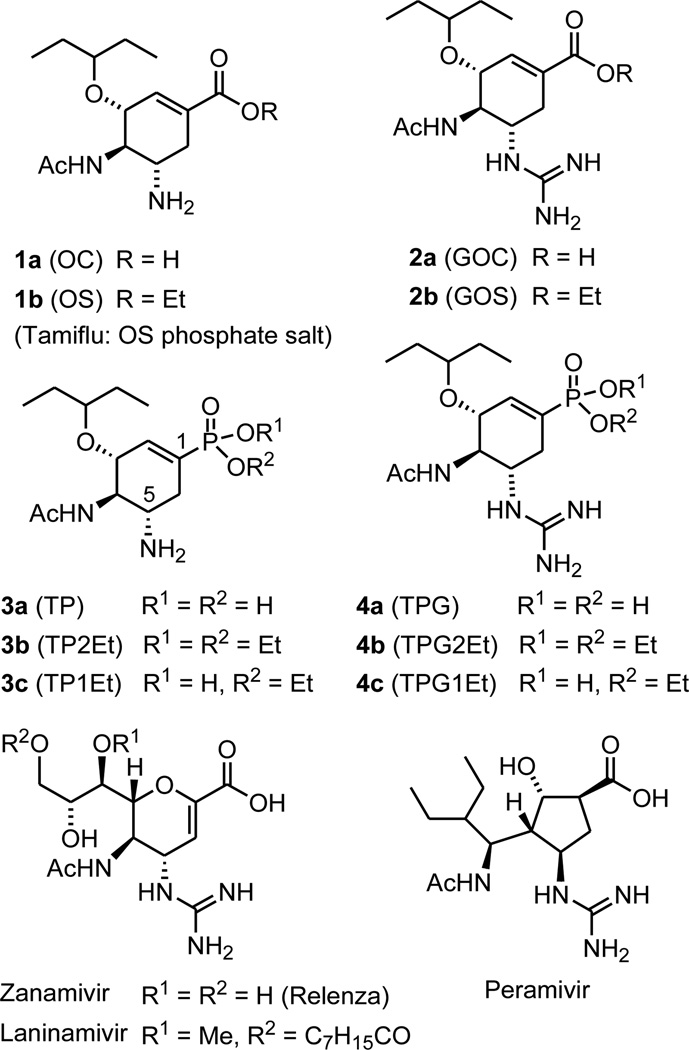

Currently the most effective anti-influenza drugs are neuraminidase (NA) inhibitors.1–3 Zanamivir (ZA) is the first marketed anti-influenza drug that is administered by inhalation or intranasal spray.4,5 The phosphate salt of oseltamivir (OS, 1b in Figure 1), is the most popular orally available drug for influenza treatment.6,7 Oseltamivir is converted by endogenous esterase to oseltamivir carboxylate (OC, 1a) which is the active inhibitor of influenza neuraminidase. Replacement of the amine group at the C-5 position with a more basic guanidino group (2a) shows better inhibitory activity than OC, presumably due to the stronger electrostatic interactions with the acidic residues of Glu119, Asp151, and Glu 227 in the active site of influenza NA.6 However, compounds 2a (GOC) and 2b (GOS) have not been developed for therapeutic use. Two other anti-NA drugs, peramivir8,9 and laninamivir10,11, were recently approved for use as intravenous and inhalation anti-influenza drugs, respectively. Due to the extensive use of oseltamivir in influenza therapy, oseltamivir-resistant viruses have emerged over the years. New anti-influenza drugs that can also inhibit oseltamivir-resistant strains, such as the H275Y mutant, are urgently needed for our battle against the threat of pandemic influenza.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of anti-influenza agents

We have recently discovered tamiphosphor (TP, 3a in Figure 1),12 an oseltamivir phosphonate congener, which is highly active for the inhibition of influenza neuraminidase and influenza virus replication. Replacement of the carboxylate group with the phosphonate group has resulted in a better binding to the neuraminidase and thus become effective against the oseltamivir-resistant mutants. Moreover, guanidino-tamiphosphor (TPG, 4a) derived by replacing the amino group at the C-5 position with a more basic guanidino group, can furthermore effectively inhibit the H275Y mutant of influenza neuraminidase. As a continuing study on the development of TP and TPG as promising anti-influenza drugs, we report herein the pharmacological, including pharmacokinetic, properties of these compounds and their monoethyl esters TP1Et (3c) and TPG1Et (4c).

RESULTS

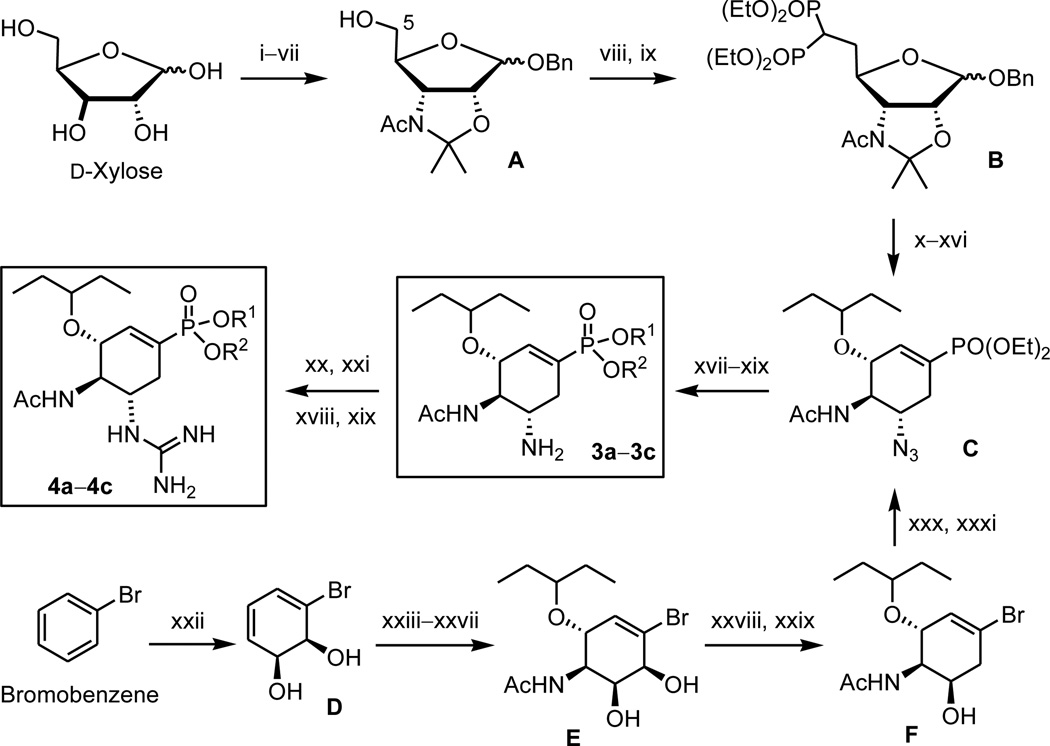

Synthesis of oseltamivir phosphonate congeners

We have previously established methods for the synthesis of oseltamivir phosphonate congeners using d-xylose or bromobenzene as the starting material (Scheme 1).12,13 In brief, d-xylose was modified to intermediate B bearing a diphosphonatomethyl substituent at the C-5 position for the subsequent intramolecular Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons reaction to construct the scaffold of cyclohexenephosphonate (C). In another approach, microbial oxidation of bromobenzene provided the enantiopure bromoarene cis-1,2-dihydrodiol (D), which was elaborated by a series of functional group transformations to give an intermediate F. Substitution of the bromine atom in F with a phosphonate group was realized by a palladium-catalyzed coupling reaction to give compound C. Reduction of the azido group in C afforded TP diethyl ester (3b). Treatment of 3b with bromotrimethylsilane gave the phosphonic acid 3a, whereas treatment with sodium ethoxide afforded the monoester 3c. By a similar procedure, the N2,N3-bis(tert-butoxycarbonyl) derivative of TPG diethyl ester (4b) was treated with bromotrimethylsilane to give TPG (4a) by concurrent removal of two diethyl groups and two tert-butoxycarbonyl groups. TPG monoester 4c was obtained by consecutive treatments of 4b with sodium ethoxide and acidic resin (Amberlite IR-120).

Scheme 1.

Outline for the syntheses of phosphonate compounds 3a–3c and 4a–4c using d-xylose or bromobenzene as the starting material. 3a and 4a: R1 = R2 = H. 3b and 4b: R1 = R2 = Et. 3c and 4c: R1 = H, R2 = Et. Reagents and conditions:12,13 (i) Me2CO, H2SO4, CuSO4, 25 °C, 24 h; (ii) 0.05 M HCl, 50 °C, 1 h; 95% (2 steps). (iii) Me3CCOCl, pyridine, 0 °C, 8 h; 89%. (iv) pyridinium dichromate, Ac2O, reflux, 1.5 h; HONH2-HCl, pyridine, 60 °C, 24 h; 82%. (v) LiAlH4, THF, 0 °C, then reflux 1.5 h; 88%. (vi) Ac2O, pyridine, 25 °C, 3 h; HCl/1,4-dioxane (4 M), BnOH, toluene, 0–25 °C, 24 h; 85%. (vii) 2,2′-dimethoxypropane, toluene, cat. p-TsOH, 80 °C, 4 h; 90%. (viii) (CF3SO2)2O, pyridine, CH2Cl2, −15 °C, 2 h; (ix) H2C[PO(OEt)2]2, NaH, cat. 15-crown-5, DMF, 25 °C, 24 h; 73%. (x) H2, Pd/C, EtOH, 25 °C, 24 h; (xi) EtONa, EtOH, 25 °C, 5 h, 80%. (xii) (PhO)2PON3, (i-Pr)N=C=N(i-Pr), PPh3, THF, 25 °C, 48 h. (xiii) HCl, EtOH, reflux, 1 h; 74%. (xiv) (CF3SO2)2O, pyridine, CH2Cl2, −15 to −10 °C, 2 h; (xv) KNO2, 18-crown-6, DMF, 40 °C, 24 h; 71%. (xvi) Cl3CC(=NH)OCHEt2, CF3SO3H, CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 24 h; 82%. (xvii) H2, Lindlar catalyst, EtOH, 25 °C, 16 h; giving 3b (85%). (xviii) treating 3b or 4b with TMSBr, CHCl3, 25 °C, 24 h; giving 3a (85%) or 4a (75%). (xix) treating 3b or 4b with EtONa, EtOH, 25 °C, 16 h; giving 3c (82%) or 4c (75%). (xx) treating 3b with N,N’-bis(tert-butoxycarbonyl)thiourea, HgCl2, Et3N, DMF, 0−25 °C, 10–16 h; 58%. (xxi) CF3CO2H, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 1 h; giving 4b (72%). (xxii) E. coli JM109 (pDTG601), 37 °C, 3.5 h; 65%. (xxiii) 2,2′-dimethoxypropane, cat. H+, acetone, 0–25 °C, 0.5 h. (xxiv) N-bromoacetamide, cat. SnBr4, H2O, CH3CN, 0 °C, 8 h; 75% (2 steps). (xxv) (Me3Si)2NLi, THF, −10 to 0 °C, 0.5 h. (xxvi) 3-pentanol, BF3·OEt2, −10 to 0 °C, 6 h; 73% (2 steps). (xxvii) conc. HCl, MeOH, 50 °C, 6 h; 94%. (xxviii) AcOCMe2COBr, THF, 0–25 °C, 3.5 h. (xxix) LiBHEt3, THF, 0–25 °C, 2 h, 82% (2 steps). (xxx) (PhO)2PON3, (i-Pr)N=C=N(i-Pr), PPh3, THF, 40 °C, 24 h; 84%. (xxxi) diethyl phosphite, cat. Pd(PPh3)4, 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane, toluene, 90 °C, 12 h; giving compound C (83%).

Inhibition of influenza neuraminidases

The structure-based design of NA inhibitors has been a successful strategy in discovery of anti-influenza drugs.14 According to the structural analysis, influenza NA interacts with the inhibitor, e.g. oseltamivir carboxylate (OC, 1a), by strong electrostatic interactions of the carboxylate group with the three arginine residues (Arg118, Arg292 and Arg371) in the active site of NA. The phosphonate group was used as a bioisostere of carboxylate in drug design,15–17 because the phosphonate ion exhibits a stronger electrostatic interaction with the guanidinium ion.18 Consistent with this rationale, tamiphosphor (3a) containing a phosphonate group was found to exhibit higher inhibitory activity than OC against various influenza viruses, including A/H1N1 (wild-type and H275Y mutant), A/H5N1, A/H3N2 and type B viruses (Table 1). As an ester, oseltamivir is inactive to NA. In contrast, TP monoester 3c is active in NA inhibition because it still retains a negative charge at the phosphonate monoester group to provide sufficient electrostatic interactions with the three arginine residues in NA. Consistent with this rationale, the NA inhibitory activity of TP diethyl ester (3b) decreased dramatically (IC50 > 3 µM) against A/WSN/33 (H1N1) virus (data not shown).

Table 1.

The IC50 values (nM) of influenza neuraminidase inhibition.a

| Virus | OC | ZA | 3a | 3c | 4a | 4c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/WSN/33 (H1N1) | 2.6±1.4 | 2.9±1.4 | 2.4±0.8 | 3.0±2.0 | 0.09±0.05 | 1.1±0.1 |

| A/WSN/33/H275Y (H1N1)b | 477±181 | 1.6±0.4 | 993±666 | 1679±43 | 0.4±0.1 | 25.1±6.6 |

| NIBRG14 (H5N1) | 0.73±0.15 | 4.8±0.2 | 0.52±0.26 | 2.2±0.6 | 0.04±0.01 | 17.4±8.6 |

| A/Taiwan/3446/2002 (H3N2) | 3.1±0.9 | 13.8±2.7 | 1.8±0.06 | 5.9±0.1 | 0.3±0.06 | 131.7±16.6 |

| A/Udorn/1972 (H3N2) | 2.9±0.4 | 22.9±7.8 | 1.6±0.6 | 3.8±1.1 | 0.35±0.05 | 114±20.3 |

| B/Taiwan/70641/2004 | 36±6.9 | 32.1±8.4 | 73.6±14 | 80.9±12.7 | 2.1±0.7 | 124.8±32.4 |

A fluorescent substrate, 2′-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-α-d-N-acetylneuraminic acid (MUNANA) was used to determine the IC50 values that are compound concentrations causing 50% inhibition of different influenza neuraminidase enzymes. Data are shown as mean ± SD of three experiments.

A/WSN H275Y virus by oseltamivir selection.

The presence of an amino group at the C-5 position enhanced the affinity of OC with the residues of Glu119, Asp151 and Glu227 in the active site of NA.1–3 Replacing the C-5 amino group with a stronger base of guanidine should increase the electrostatic interactions with the acidic residues in the NA active site. Indeed, TPG (4a) showed an enhanced NA inhibitory activity in comparison with OC and ZA. Notably, TPG and its monoester 4c also showed remarkable inhibitory activities against the H275Y oseltamivir-resistant strain with IC50 values of 0.4 and 25 nM, respectively.

Inhibition of viruses in cell culture

The anti-influenza activities of phosphonate compounds 3a, 3c, 4a and 4c were examined using a variety of influenza strains (Table 2). All four compounds are very potent anti-influenza agents with EC50 values ranging from low nM to pM levels. Comparable anti-influenza activities were noted between the phosphonic acids and phosphonate monoesters (3a vs. 3c, and 4a vs. 4c), even though the phosphonic acids were more potent NA inhibitors than the monoesters (Table 1). This result may be due to the improved lipophilicity of monoesters with enhanced intracellular uptake. We also noted that guanidino-tamiphosphor (4a) and its monoester 4c were effective against the oseltamivir-resistant influenza strains in the cell-based assays. The anti-influenza cell protection activity of TPG monoester 4c (EC50 = 0.9–1.0 µM) against oseltamivir-resistant influenza was more potent than oseltamivir (EC50 >10 µM) by over 10 fold. With regard to toxicity, the potent anti-influenza agents 3a, 3c, 4a and 4c were nontoxic to MDCK cells at the highest testing concentrations (>100 µM).

Table 2.

The EC50 values (µM) against different influenza viruses determined by cytopathic effect inhibition assays.a

| Virus | 3a | 3c | 4a | 4c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/WSN/33 (H1N1) | 0.084±0.016 | 0.047±0.004 | 0.36±0.283 | 0.18±0.014 |

| A/CA/07/2009 (pandemic H1N1) | 0.235±0.16 | 0.165±0.007 | 3.6±0.5 | 1.4±0.283 |

| A/WSN/33/H275Y (H1N1)b | 7.4±3.7 | 0.49±0.47 | 3.2±0.6 | 0.9±0.2 |

| A/Hong Kong/2369/09/H275Y (pandemic H1N1) | 6.55±0.36 | 0.44±0.09 | 4.6±2.7 | 1.0±0.22 |

| A/Brisbane/10/2007 (H3N2) | >10 | >10 | >10 | >10 |

| A/Victoria/3/75 (H3N2) | 0.043±0.04 | 0.041±0.05 | 0.035±0.04 | 0.034±0.04 |

| A/Panama/2007/99 (H3N2) | 0.008±0.001 | 0.002±0.005 | 0.007±0.0001 | 0.014±0.003 |

| A/Duck/MN/1525/81 (H5N1) | 0.007±0.0003 | 0.005±0.0006 | 0.475±0.049 | 0.2±0.004 |

| B/Florida/4/2006 | 2.0±0.28 | 1.1±0 | >10 | >10 |

| B/Sichuan/379/99 | 4.25±0.64 | 0.695±0.31 | >10 | >10 |

The anti-influenza activities against different influenza strains were measured as EC50 values that are the compound concentrations for 50% protection of the cytopathic effects due to the infection by different influenza strains. Data are shown as mean ± SD of three experiments.

A/WSN reassortant H275Y virus.

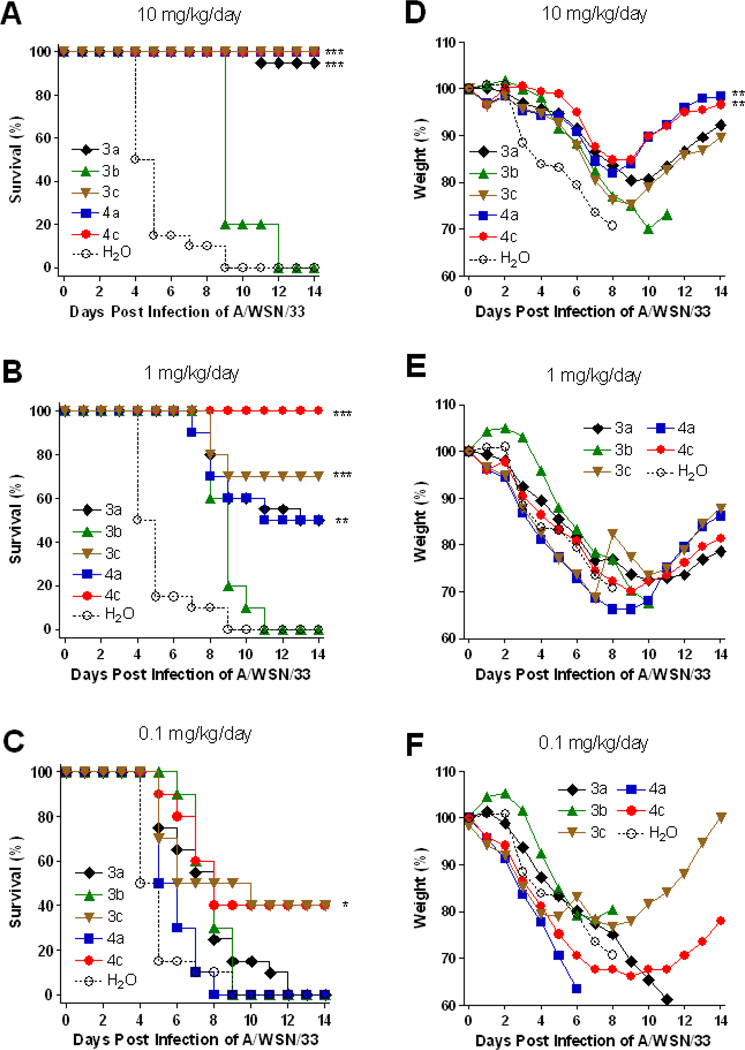

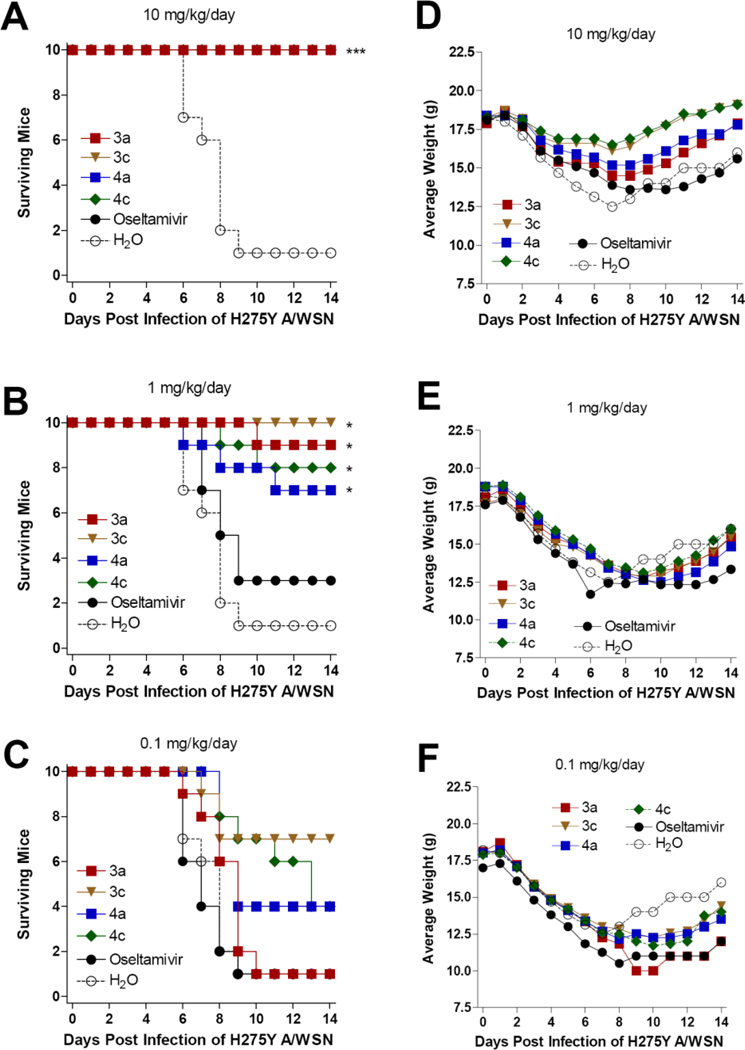

Animal experiment against A/WSN/33 (H1N1) virus

We then examined if the phosphonate compounds can protect mice from virus-induced mortality and weight loss. When compounds 3a, 3c, 4a and 4c were administered orally to virus A/WSN/33-infected mice at 10 mg/kg/day, the mice survived and the weight recovered gradually 8 days after infection (Figures 2A and 2D). No significant protection was observed on treatment with the phosphonate diester 3b, consistent with its low NA inhibitory activity due to the lack of an ionic phosphate moiety to interact with the three arginine residues in NA. Unlike OS which is readily subject to enzymatic hydrolysis to give active OC, there is no corresponding endogenous phosphotriesterase to cleave the diethyl groups in 3b. When the infected mice were treated with test compounds at 1 mg/kg/day, TPG monoester 4c showed better protection activity in mice survival than other compounds (Figures 2B and 2E). The phosphonate monoesters 3c and 4c at 0.1 mg/kg/day can still exert partial protection (Figures 2C and 2F), indicating that these two compounds may have superior efficacy in the mouse infection model.

Figure 2.

Percentage of survival (A, B, C) and average body weight (D, E, F) of mice orally administered with test compounds at indicated concentrations twice per day and challenged with 10× LD50 of A/WSN/33 (H1N1) influenza virus. The number of mice and the average weight of the mice at day 0 (10 mice per group) were defined as 100%, respectively. ***: P < 0.0001. **: P < 0.001. *: P < 0.05.

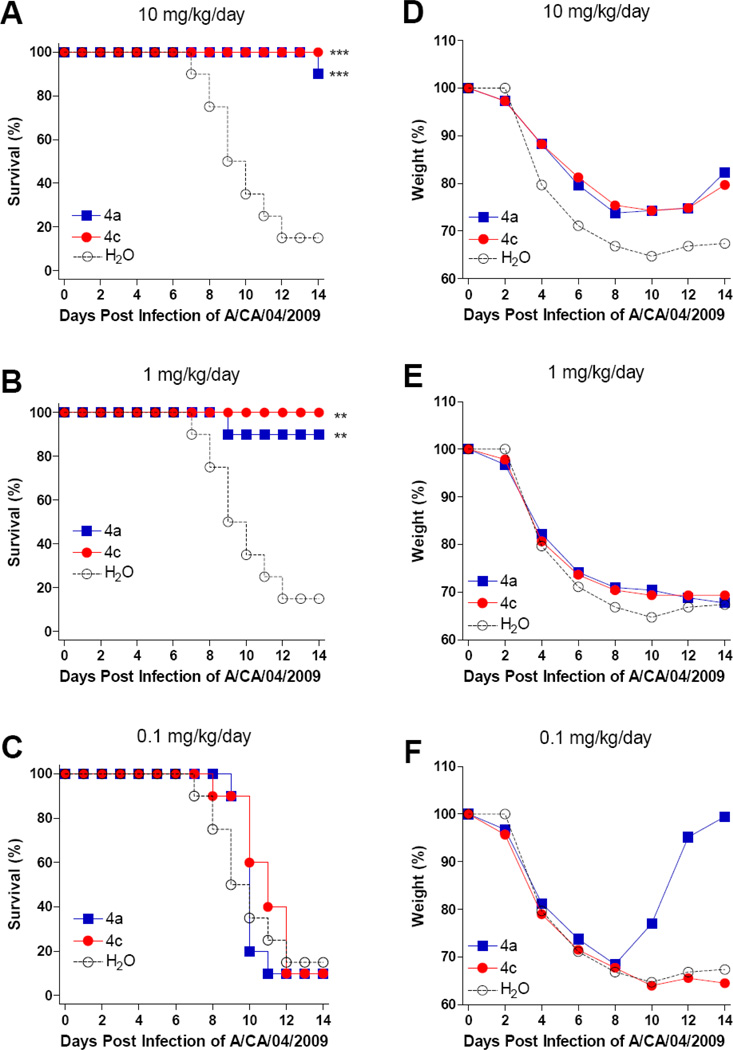

Animal experiment against A/CA/04/2009 (H1N1, pandemic) virus

Compounds 4a and 4c were further tested for their activities against pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus A/CA/04/2009 infection in BALB/c mice. Both compounds were orally administered twice daily using 0.1, 1.0, and 10 mg/kg/day doses and were compared to groups of mice receiving water under the same treatment regimen. Mice were treated for 5 days beginning 4 hours before virus exposure and observed for weight loss and mortality following virus challenge.

Figure 3 shows the survival results (A, B and C) and weight changes (D, E and F) following nasal virus challenge. The survivals of the groups treated with 10 and 1 mg/kg/day were significantly different from the control group (Figures 3A and 3B). However, the body weight recovery was slow and slight in mice treated with 4a or 4c at 10 mg/kg, while the body weight recovery was not observed in mice treated with either compound at 1 mg/kg (Figures 3D and 3E). In fact, low body weights persisted through day 20 and a number of mice died late in the study on days 20 and 21 (data not shown). For the group treated with compounds at 0.1 mg/kg/day, no significant protection was observed except a single mouse that rapidly recovered in the group treated with 4a (Figures 3C and 3F).

Figure 3.

Percentage of survival (A, B, C) and average body weight (D, E, F) of mice orally administered with various compounds at indicated concentrations and challenged with 1 × 105 (3× LD50) cell culture infectious doses (TCID50) of influenza A/CA/04/2009 (H1N1) virus. Mice were orally administered with test compounds 4 hours prior to virus challenge and every day at a 12 hour interval as indicated. The number of mice and the average weight of the mice at day 0 (10 mice per group) were defined as 100%, respectively. ***: P < 0.0001. **: P < 0.001.

Animal experiment against oseltamivir-resistant H275Y H1N1 virus

We further examined if these four phosphonate compounds, 3a, 3c, 4a and 4c, could protect mice against a challenge infection with an oseltamivir-resistant influenza A (H1N1) virus A/WSN/33/H275Y in 10× LD50. All the four compounds and oseltamivir completely protected mice from death as well as weight loss at the 10 mg/kg/day dose (Figures 4A and 4D). At the dose of 1 mg/kg/day, significant protection to improve mice survival was observed in the groups treated with phosphonates (3a, 3c, 4a, or 4c) compared to oseltamivir or water-treated mice (Figures 4B and 4E). No significant protection was noted by any compound treated at the dose of 0.1 mg/kg/day (Figures 4C and 4F). These data indicate that the phosphonate congeners are superior to oseltamivir in improving the survival of infected mice when challenged with oseltamivir-resistant influenza A (H1N1) viruses.

Figure 4.

Survival (A, B, C) and body weight (D, E, F) of mice challenged with 10× LD50 of oseltamivir-resistant influenza H275Y (A/WSN reassortant) virus. Mice were orally administered with test compounds 4 hours prior to virus challenge and every day at a 12 hour interval as indicated. ***: P < 0.0001. *: P < 0.05.

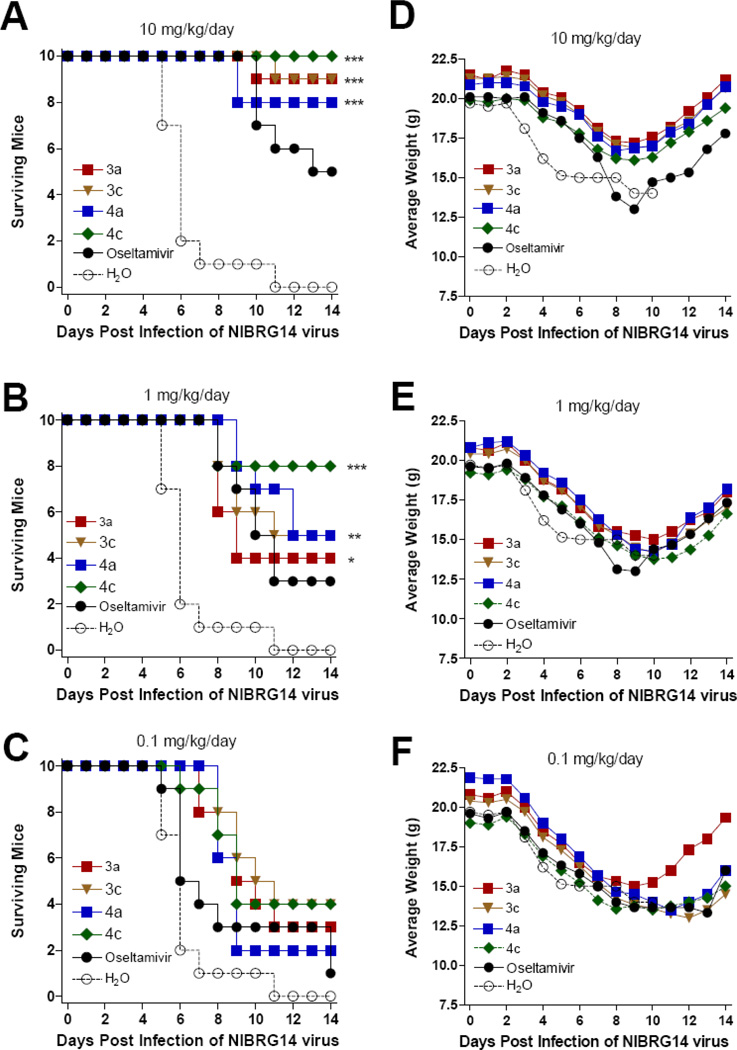

Animal experiment against avian influenza H5N1 virus

We also examined the dose responsive effect of the compounds against a challenge infection with reassortant virus NIBRG-14, which contains HA and NA genes from the A/Viet Nam/1194/2004 (H5N1). At the dose of 10 mg/kg/day, significant protections were noted in mice treated with all tested oseltamivir phosphonate congeners compared to the mice treated with water (Figures 5A and 5D). No statistically significant differences were observed among these four treatment groups, though the phosphonate congeners showed a somewhat more beneficial effect than oseltamivir. At the dose of 1 mg/kg/day compounds, the treated groups provided partial protection against virus challenge relative to the mice treated with water (Figures 5B and 5E). At the dose of 0.1 mg/kg/day, no treatment groups showed statistically significant protection (Figures 5C and 5F).

Figure 5.

Survival (A, B, C) and average body weight (D, E, F) of mice challenged with 10× LD50 of NIBRG-14 A/Vietnam/1194/2004 (H5N1) influenza virus. Mice were orally administered with test compounds at indicated concentrations per day. ***: P<0.0001. **: P<0.001. *: P < 0.05.

In summary, the mouse experiments demonstrated the antiviral efficacy of oseltamivir phosphonate congeners, especially the guanidino compounds 4a and 4c, by improving mouse survival at the dose of 10 or 1 mg/kg/day following challenge with A/WSN/33 (H1N1), A/CA/04/2009 (H1N1), A/WSN/33/H275Y (oseltamivir-resistant strain) or avian H5N1 influenza viruses.

Partition of anti-influenza compounds between octanol and phosphate buffer

Lipophilicity is an important factor for the pharmacokinetic behavior of drugs. A measure of lipophilicity can be deduced from the partition coefficient (P) of a compound between octanol and water. Most oral drugs are found to have the log P values between −1 and 5.19 In lieu of log P, the distribution coefficient (log D) is generally used to represent the partition of an ionic compound between octanol and PBS buffer. OC exhibits a high polarity with log D value of − 1.50 at pH 7.4,20 whereas OS is an oral drug with an improved lipophilicity (log D = 0.36) by changing the carboxylic group in OC to the ethyl ester. Table 3 shows the calculated and measured values of log D for a series of oseltamivir and phosphonate derivatives. All the diethyl and monoethyl ester derivatives with increased lipophilicity had higher log D values than their parent acids. Despite having double negative charges on the phosphonate group, tamiphosphor 3a (log D = −1.04) appeared to be less hydrophilic than OC (log D = −1.69) that carries a single negative charge. Interestingly, we also found that guanidino compounds 2a (log D = −1.41), and 4c (log D = −0.37) were more lipophilic than their corresponding amino compounds 1a (log D = −1.69) and 3c (log D = −0.75). This result was in agreement with the trend of calculation (clog D). The improved lipophilic property of 2a and 4c might be related to their zwitterionic structures, in which the C-5 guanidinium could pair intramolecularly with the carboxylate or phosphonate (single-charged) groups.21,22

Table 3.

Distribution coefficients of anti-influenza compounds between octanol and PBS buffer.

| Entry | Compound | cLog Pa | cLog Db | Log Dc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1a (OC) | 0.45 | −1.84 | −1.69 ± 0.16 (−1.50)d |

| 2 | 1b (OS) | 1.49 | −0.72 | (0.36)d |

| 3 | 2a (GOC) | −0.22 | −1.55 | −1.41 ± 0.24 |

| 4 | 2b (GOS) | 0.83 | 0.73 | 0.31 ± 0.05e |

| 5 | 3a (TP) | −1.25 | −2.42 | −1.04 ± 0.14 |

| 6 | 3b (TP2Et) | 2.18 | −1.39 | 0.22 ± 0.04 |

| 7 | 3c (TP1Et) | −0.14 | −1.52 | −0.75 ± 0.10 |

| 8 | 4a (TPG) | −1.92 | −2.17 | −0.98 ± 0.18 |

| 9 | 4b (TPG2Et) | 1.51 | −1.93 | −0.10 ± 0.04 |

| 10 | 4c (TPG1Et) | −0.81 | −1.27 | −0.37 ± 0.02 |

Calculated values using Advanced Chemistry Development (ACD/Labs) Software V12.01.

Calculated values using MarvinSketch (http://www.chemaxon.com/marvin/sketch/index.html)

Octanol–water partition coefficient determined at pH 7.4 from five repeated experiments.

Log D value at pH 7.4 (adapted from ref 20).

Log D value at pH 7.4 (adapted from ref 22).

Stability in simulated gastric fluid

Compound 4c was stable in simulated gastric fluid (SGF, without enzymes), and 87% of 4c remained after incubation for 30 min at room temperature (data not shown). No apparent precipitation was observed. According to the LC/MS/MS analysis, there was no statistically significant difference by incubation in the presence or absence of SGF.

Metabolic stability in human, dog and rat whole blood

TPG monoester 4c was found to be relatively stable in human, rat and dog whole blood (Figure s1 in Supporting Information (SI)). No significant levels of free phosphonate metabolite 4a (m/z 363.4 [M + H]+) were found by using LC/MS/MS analysis.

Metabolic stability in human, dog and rat liver microsomes

The metabolic stability of compound 4c was further tested in pooled human, male rat, and male dog liver microsomes (Table s1 in SI). No significant levels of the metabolite 4a (m/z 363.4 [M + H]+) were found by using LC/MS/MS analysis. The intrinsic clearance (CL) of 4c was very low (<2 µL/min/mg proteins), and the in vitro half life (t1/2) was long (>12 h). In contrast, the control compounds (testosterone and midazolam) were readily metabolized (65–100% in 1 h) in human, male rat, and male dog liver microsomes.

Metabolic stability in fresh human liver microsomes

Metabolic stabilities of the phosphonate compounds 3a, 3c, 4a, and 4c were tested in five fresh, pooled human liver microsome preparations using the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system (with cofactor NADPH) or the uridine 5'-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) system (with cofactor UDPGA). The remaining levels of intact compounds 3a, 3c, 4a and 4c were 107 ± 8, 92 ± 3, 92 ± 7 and 99 ± 5 % in the CYP system at the end of the tests (1, 0.75, 1 and 0.5 h incubation, respectively), indicating no significant metabolism of any of the compounds by CYP enzymes. Compounds 4a and 4c were also stable in the UGT system, with 90 ± 6 and 91 ± 3 % remaining of intact compounds, respectively, after 1 h and 0.5 h incubation. The stabilities of compounds 3a and 3c in the UGT system were not tested.

Protein binding measurements in human, rat and dog plasma

Plasma protein binding of TPG monoester 4c in human, rat and dog plasma was determined by rapid equilibrium dialysis followed by LC/MS/MS analysis. Compound 4c showed a high free fraction (86–91%) in plasma from all three species (Table s2 in SI). This result was consistent with the studies using microsome systems, which showed no significant conversion of the monoester 4c to the phosphonic acid metabolite 4a.

Pharmacokinetic studies in rats with compounds dissolved in normal saline

The pharmacokinetic parameters for compounds 3a, 3c, 4a and 4c in Sprague-Dawley rats are listed in Table 4. After intravenous (i.v.) administration, the half-lives of four compounds ranged from 0.54 to 3.36 h. The CL/F values ranged from 0.40 to 0.83 L/h/kg. After oral administration, the half-lives of compounds 3a, 4a and 4c ranged from 1.07 to 3.05 h. The CL/F values of the three compounds ranged from 22.1 to 65.1 L/h/kg. The absolute oral bioavailabilities (F values) of compounds 3a, 4a and 4c were 2.33 ± 1.21, 3.20 ± 1.48 and 1.20 ± 0.16 %, respectively. The plasma concentrations of compound 3c after oral administration were below the detection limit (Figure s2 in SI), so the corresponding pharmacokinetic parameters could not be deduced. This study indicated that the absolute oral bioavailability of all four compounds in normal saline was very low with relatively short half-lives in rats.

Table 4.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of test compounds after single i.v. bolus or oral administration to male rats

| PK Parameter (unit) |

3a | 3ca | 4a | 4c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV 1 mg/kg (N = 6) |

Oral 1 mg/kg (N = 6) |

IV 1 mg/kg (N = 6) |

IV 0.5 mg/kg (N = 6) |

Oral 3 mg/kg (N = 6) |

IV 0.3 mg/kg (N = 6) |

Oral 5 mg/kg (N = 6) |

|

| k (1/h) | 0.213±0.041 | 0.265±0.127 | 0.428±0.138 | 0.902±0.251 | 0.485±0.090 | 1.285±0.037 | 0.669±0.126 |

| AUC0→t (h*ng/mL) | 2620±671 | 51.04±28.95 | 1267±336 | 666±171 | 116.7±54.5 | 389±35 | 69.6±10.2 |

| AUC0→∞ (h*ng/mL) | 2634±672 | 55.69±25.51 | 1286±344 | 669±173 | 128.4±59.4 | 390±36 | 77.9±10.3 |

| T1/2 (h) | 3.36±0.63 | 3.05±1.17 | 1.80±0.72 | 0.83±0.25 | 1.47±0.24 | 0.54±0.02 | 1.07±0.21 |

| CL/F (L/h/kg) | 0.40±0.10 | 22.10±9.48 | 0.83±0.25 | 0.79±0.21 | 28.3±13.4 | 0.77±0.08 | 65.1±8.3 |

| Vd/F (L/kg) | 1.87±0.19 | 106.76±73.43 | 2.29±1.58 | 0.91±0.21 | 59.6±27.3 | 0.60±0.06 | 100.9±26.4 |

| MRT (h) | 1.47±0.25 | 4.40±0.64 | 1.44±0.79 | 0.66±0.06 | 2.40±0.57 | 0.53±0.03 | 2.05±0.27 |

| F (%) | 100 | 2.33±1.21 | 100 | 100 | 3.20±1.48 | 100 | 1.20±0.16 |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | – | 12.92±7.60 | – | – | 73.1±81.7 | – | 25.8±4.4 |

| Tmax (h) | – | 1.46±1.36 | – | – | 0.88±0.21 | – | 1.38±0.59 |

The pharmacokinetic parameters for compound 3c in oral administration could not be deduced because its plasma concentrations were lower than the detection limit.

Pharmacokinetic studies in mice with compounds in normal saline

Table 5 shows the pharmacokinetic parameters in mice. After i.v. administration, the half-lives of compounds 4a and 4c were 0.53 ± 0.25 and 0.71 ± 0.57 h, respectively. The CL/F values were 0.69 ± 0.12 and 0.47 ± 0.08 L/h/kg for compounds 4a and 4c, respectively. After oral administration, the half-lives of compounds 4a and 4c were 2.44 ± 0.61 and 2.57 ± 1.54 h, respectively. The CL/F values were 10.30 ± 2.88 and 4.75 ± 2.12 L/h/kg for compounds 4a and 4c, respectively. The oral bioavailability of compounds 4a (7.0 ± 2.4 %) and 4c (12.1 ± 6.7 %) in mice were appreciably higher than that in rats.

Table 5.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of compounds 4a and 4c after single i.v. bolus or oral administration to male mice

| PK Parameter (unit) |

4a | 4c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV 0.25 mg/kg (N = 6) |

Oral 10 mg/kg (N = 6) |

IV 0.25 mg/kg (N = 6) |

Oral 10 mg/kg (N = 6) |

|

| k (1/h) | 1.564±0.729 | 0.300±0.073 | 1.368±0.625 | 0.364±0.208 |

| AUC0→t (h*ng/mL) | 354±73 | 939±346 | 529±103 | 2575±1441 |

| AUC0→∞ (h*ng/mL) | 373±72 | 1050±355 | 541±108 | 2629±1449 |

| T1/2 (h) | 0.53±0.25 | 2.44±0.61 | 0.71±0.57 | 2.57±1.54 |

| CL/F (L/h/kg) | 0.69±0.12 | 10.30±2.88 | 0.47±0.08 | 4.75±2.12 |

| Vd/F (L/kg) | 0.51±0.18 | 36.04±15.00 | 0.44±0.24 | 20.00±18.59 |

| MRT (h) | 0.58±0.20 | 3.61±0.81 | 0.63±0.22 | 3.14±0.60 |

| F (%) | 100 | 7.0±2.4 | 100 | 12.1±6.7 |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | – | 337±224 | – | 935±536 |

| Tmax (h) | – | 1.33±0.52 | – | 1.38±0.59 |

According to the plasma concentration–time curves for i.v. and oral administrations of compound 4a to mice (Figure s3 in SI), the average concentration of 4a in plasma at 8 h after oral administration was 31.4 ng/mL (~87 nM), which was higher than all EC50 values of the tested viruses. The average concentration of compound 4c at 12 h was 16.8 ng/mL (~43 nM), which was also higher than the EC50 values of the tested viruses. These results might account for the high survival rates in the influenza-infected mice even though compounds 4a and 4c had only modest absolute bioavailability.

Pharmacokinetic studies in rats and dogs with compound 4c in 20% HP-β-CD aqueous solution or in microcrystalline cellulose

To investigate whether bioavailability of the test compound can be improved by adding pharmaceutical excipients, compound 4c was dissolved in a 20% 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HP-β-CD) aqueous solution for i.v. administration or in microcrystalline cellulose for oral administration. A summary of the pharmacokinetic parameters determined in rats and dogs is shown in Table 6. After i.v. administration, the half-lives of compound 4c in rat and dog were 4.3 and 5.65 h, respectively, with corresponding CL values of 10.7 and 3.4 mL/min/kg. After oral administration, the half-lives of compound 4c in rat and dog were 2.2 and 5.5 h, respectively. The oral bioavailabilities of compound 4c in rat and dog were 6.0 and 11.2 %, respectively. No clear evidence of bioconversion of monoester 4c to its free phosphonic acid 4a was observed. Though the bioavailability of 4c is not yet optimal for convenient oral dosing, this study indicates the possible improvement by formulation enhancements.

Table 6.

Pharmacokinetic studies in rats and dogs with compound 4c in 20% HP-β-CD aqueous solution (i.v. administration) or in microcrystalline cellulose (oral administration).

| PK Parameter (unit) |

Rat | Dog | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I.V. 2 mg/kg (N = 4) |

Oral 50 mg/kg (N = 4) |

I.V. 5 mg/kg (N = 4) |

Oral 20 mg/kg (N = 4) |

|

| k (1/h) | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.31 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 0.13 ± 0.03 |

| AUC0→t (h*ng/mL) | 3168 ± 492 | 4763 ± 1080 | 24516 ± 1918 | 11019 ± 2975 |

| AUC0→∞ (h*ng/mL) | 3170 ± 492 | 4610 ± 1053 | 24641 ± 1936 | 11561 ± 3210 |

| T1/2 (h) | 4.3 ± 0.28 | 2.2 ± 0.08 | 5.65 ± 1.30 | 5.50 ± 1.20 |

| CL/F (L/h/kg) | 0.64 ± 0.09 | – | 3.40 ± 0.27 | |

| Vd/F (L/kg) | 0.33 ± 0.03 | – | 0.341 ± 0.015 | |

| MRT (h) | 0.5 ± 0.03 | 5.6 ± 0.23 | 1.52 ± 0.139 | 5.12 ± 0.694 |

| F (%) | 100 | 6.0 ± 1.4 | 100 | 11.2 ± 2.73 |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | – | 482 ± 153 | – | 2423 ± 591 |

| Tmax (h) | – | 3.7 ± 3.9 | – | 1.50 ± 0.577 |

Excretion study

After oral administration of compound 4c (5 mg/kg) to rats, the recovery of phosphonate monoester 4c from urine and feces was 1.5 ± 0.4 and 43.2 ± 12.0 %, respectively (Table s3 in SI). In the mean time, the free phosphonic acid 4a, presumably a degradation product of 4c, was also obtained from urine and feces at 0.4 ± 0.2 and 27.0 ± 3.0 %, respectively. The total recovery of compounds 4c plus 4a was estimated to be 1.9 ± 0.5 % from urine and 70.2 ± 12.1 % from feces.

Study of acute toxicity in mice

Acute toxicity was studied in female Crl:CD1® (ICR) mice (20–30 g and 6–7 weeks old). Tamiphosphor (3a) dissolved in water-for-injection (WIF), with solubility up to 50 mg/mL, was administered by a single i.v. injection. TP monoester 3c was suspended in carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) aqueous solution (0.5%, w/v) up to 30 mg/mL and applied by a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection. Acute toxicity was assessed by major clinical signs including tremor, convulsion, body jerks, hypoactivity, hunched posture and piloerection (Table s4 in SI). Mortality in the treated animals occurred by i.v. dosing of tamiphosphor 3a above 750 mg/kg or by i.p. dosing of tamiphosphor monoester 3c at 2000 mg/kg. Clinical signs of acute toxicity which occurred in survivors were reversed within 2 days after dosing. No gross lesions were observed upon necropsy of sacrificed animals after 15-days on study.

DISCUSSION

Tamiphosphor (3a), its monoester 3c, guanidino-tamiphosphor (4a) and its monoester 4c were synthesized and found to be potent inhibitors for influenza neuraminidases (Table 1). Phosphonates 3a and 4a are significantly more potent than their carboxylate congeners 1a (OC) and 2a (GOC) presumably due to the stronger binding of phosphonate with the three arginine residues (Arg118, Arg292 and Arg371) in the active site of NA. Unlike oseltamivir (1b), TP monoester 3c and TPG monoester 4c still possess effective NA inhibitory activities because the negative charge at the phosphonate monoester group provides the necessary electrostatic interactions with the three arginine residues in NA. Compounds 3a, 3c, 4a and 4c inhibited the replication of different strains of influenza viruses at low nM to pM levels (Table 2). In general, the phosphonate compounds 4a and 4c bearing a guanidino group at the C-5 position are more potent than the C-5 amino analogues 3a and 3c in inhibiting NA activity and virus replication of the oseltamivir-resistant viruses.

Owing to the intrinsic high anti-influenza activities, all four phosphonate compounds (3a, 3c, 4a and 4c) can significantly protect mice infected with several tested influenza strains (human H1N1, pandemic H1N1, H275Y H1N1 mutant and avian H5N1) when administered at doses of 1 mg/kg/day or higher (Figures 2–5). Consistent with in vitro virus replication tests, the phosphonate congeners did show good protection against the challenge with oseltamivir-resistant A/WSN/33/H275Y virus.

The potent anti-influenza activity of tamiphosphor monoesters (3c and 4c), nearly equal to that of the free phosphonic acids (3a and 4a), may be surprising given that there was little evidence of bioconversion of the monoesters to the free phosphonic acids in metabolism studies. Perhaps the higher lipophilicity of monoester compounds resulted in higher intracellular concentrations of the compounds which, in turn, resulted in greater than expected anti-influenza activity. It has been shown that GOS (2b) having a guanidino group in lieu of the amino group in OS is no longer available to esterase digestion.23 It is conceivable that guanidino-tamiphosphor monoethyl ester (4c) cannot be converted to the free acid 4a; however, little of bioconversion of 3c is not expected. As the strategy used for laninamivir24 and phospho-sulindac25, addition of long aliphatic chain to phosphonate compounds 3a, 3c, 4a and 4c may provide more efficient bioconversion, which is required to achieve higher levels of antiviral activity against oseltamivir-resistant influenza viruses.

The results presented in this study indicate that phosphonate compounds 3a, 3c, 4a and 4c have similar pharmacokinetic properties (Tables 4–6). GOC (2a) was reported to have longer half-life (20.1 h) than OC (10.6 h) in rats.23 In contrast, slight decrease in half-life of guanidino-tamiphosphor (4a) was found by replacement of the amino group in TP (3a) with a guanidino group. The compound half-lives were shorter than 4.5 h in rats and mice, but slightly longer in dogs at about 5.5 h. The absolute oral bioavailability of all four compounds (as saline solutions) in rats was low (≤3.20 ± 1.48 %). However, the oral bioavailability of compounds 4a and 4c in mice was higher (up to 12.1 ± 6.7 %) than in rats. Our study also indicates that formulation of 4c in microcrystalline cellulose can improve its absolute oral bioavailability to 6% in rats and 11.2 ± 2.73 % in dogs. Despite low bioavailability, phosphonates 3a, 3c, 4a and 4c can generally maintain the plasma concentrations in mice above the concentration required to inhibit the influenza viruses (Table s2 in SI), consistent with the observed protection against lethal infection in mice. As the level of plasma protein binding was low, the circulating compound would be almost entirely free of bound protein and available to exert antiviral activity in vivo.

Based on the in vitro metabolism studies, none of the phosphonate compounds are metabolized extensively by CYP or UGT enzymes in vivo, nor is there evidence of bioconversion of phosphonate monoesters to free phosphonic acids in liver microsomes or whole blood. These findings are consistent with the observation in pharmacokinetic studies, which showed negligible accumulation of phosphonic acid 4a after administration of monoester 4c. After oral administration, in fact, most of 4c (43%) and its degradation product 4a (27%) were excreted in feces. Thus, compound 4c might be biotransformed to 4a in gastrointestinal tract extensively. The low oral bioavailability of 4c may be due to incomplete absorption as well as partial biotransformation to 4a in gastrointestinal tract.

As shown in this study, substitution of the carboxylate in OC (1a) by phosphonate, giving tamiphosphor 3a, and further substitution of the amine by guanidine, giving TPG 4a, all provide better affinity to influenza neuraminidases, and thus enhance the potency against influenza viruses. However, incorporation of the charged phosphate and guanidinium ions in 3a and 4a also causes problem in pharmacokinetics. Poor absolute oral bioavailability (<5%) has also been encountered in the anti-influenza agents OC (4.3%), guanidino-OC (2a, 4.0%) and zanamivir (3.7%).23 The problem in OC has been solved by preparation of its ethyl ester (OS) as a prodrug with good oral bioavailability (35%) and high peak concentration (Cmax = 0.47 µg/mL) in plasma.26 Formulation of the OS phosphate salt with appropriate filler materials further improves its bioavailability to 79% for marketing as the Tamiflu capsule. The half-life and bioavailability of compounds 3a and 4a are comparable to that of ZA (1.8 h and 3.7 %).23 To develop 3a and 4a with non-oral administration is possible.27

As the first approach to improve the pharmacokinetic properties of tamiphosphor 3a and TPG 4a, we synthesized the monoethyl ester derivatives 3c and 4c to investigate their pharmaceutical properties. Compound 4c (as the saline solution) did show better bioavailability (F = 12%) than 4a (F = 7%) in mice, but not in rats. Using microcrystalline cellulose as the excipient, the bioavailability of 4c was appreciably improved in rats and was nearly 12% in dogs. It seems promising to design other tamiphosphor prodrugs using varied monoesters to attain better bioconversion and biopharmaceutical properties.28 In contrast, to develop positively-charged guanidine-containing compounds into orally available drugs is still a challenging task.29 Even so, considerable progress has been made to improve the permeability and possible oral bioavailability of ZA, for example, by encapsulation with liposome,30 by ion-pairing with 2-hydroxynaphthoic acid,21 and by a prodrug moiety targeting intestinal membrane carriers.31 These new strategies and mechanisms of advanced formulation and structural modification for enhancing oral bioavailability of phosphate- and guanidine-containing compounds may be applied to develop highly potent anti-influenza agents 4a and 4c for practical therapeutic use.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials and Methods

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+), glucose-6-phosphate (G6P), glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD), magnesium chloride, uridine 5′-diphosphoglucuronic acid (UDPGA) and alamethicin were purchased from Sigma. Phosphate buffer was prepared from potassium dihydrogenphosphate (KH2PO4) purchased from Nacalai Tesque Incorporation. Acetonitrile and methanol were purchased from J. T. Baker and formic acid was from Sigma-Aldrich. The solution of NH4OH (5%) in MeOH was purchased from Fluka. The reagents for cell culture including DMEM (Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium), fetal bovine serum, and penicillin-streptomycin were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

All the reagents were commercially available and used without further purification unless indicated otherwise. All solvents were anhydrous grade unless indicated otherwise. All non-aqueous reactions were carried out in oven-dried glassware under a slight positive pressure of argon unless otherwise noted. Reactions were magnetically stirred and monitored by thin-layer chromatography on silica gel. Flash chromatography was performed on silica gel of 60–200 µm particle size. Melting points were recorded on an Electrothermal MEL-TEMP® 1101D melting point apparatus and were not corrected. NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker AVANCE 600 and 400 spectrometers. Chemical shifts are given in δ values relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS); coupling constants J are given in Hz. Internal standards were CDCl3 (δH = 7.24), MeOH-d4 (δH = 3.31) or D2O (δH = 4.79) for 1H-NMR spectra, CDCl3 (δc = 77.0) or MeOH-d4 (δc = 49.15) for 13C-NMR spectra, and H3PO4 in D2O (δP = 0.00) for 31P-NMR spectra. The splitting patterns are reported as s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), q (quartet), m (multiplet), br (broad) and dd (double of doublets). IR spectra were recorded on a Thermo Nicolet 380 FT-IR spectrometer. Optical rotations were recorded on a Perkin-Elmer Model 341 polarimeter. High resolution ESI mass spectra were recorded on a Bruker Daltonics spectrometer.

Oseltamivir carboxylic acid (1a, OC), oseltamivir (1b, OS, Tamiflu® as the phosphate salt), guanidino-OC (2a, GOC), guanidino-OS (2b, GOS), zanamivir (ZA, Relenza®), and the oseltamivir phosphonate congeners including tamiphosphor (3a, TP), tamiphosphor diethyl ester (3b, TP2Et), guanidino-tamiphosphor (4a, TPG), and guanidino-tamiphosphor diethyl ester (4b, TPG2Et) were prepared in our laboratory according to the previously reported procedures.12,13 The synthetic procedures for tamiphosphor monoethyl ester (3c, TP1Et) and guanidino-tamiphosphor monoethyl ester (4c, TPG1Et) are described as follows. Purity of these compounds was assessed to be ≥95% by HPLC analyses (Agilent 1100 series) on an HC-C18 column (5 µm porosity, 4.6 × 250 mm) using MeOH/H2O (1:1) as the eluent and UV detector at λ = 214 nm.

Tamiphosphor monoethyl ester (3c)

To a solution of tamiphosphor diethyl ester 3b (1.43 g, 3 mmol) in ethanol (50 mL) was treated with sodium ethanoate in ethanol (4.5 mmol, 4.5 mL of 1 M solution) under a nitrogen atmosphere. The mixture was stirred for 16 h at room temperature, and then acidified with Amberlite IR-120 (H+-form). The heterogeneous solution was stirred at 40 °C for 2 h, filtered and concentrated in vacuo. The residual oil was taken up in water (15 mL) and subjected to lyophilization. The residual colorless solids were washed with cold acetone (20 mL × 3), dissolved in aqueous NH4HCO3 (15 mL of 0.1 M solution), stirred for 1 h at room temperature, and then lyophilization to afford ammonium salt of TP monoethyl ester 3c (898 mg, 82%) as white solids. The purity of product was >98% as shown by HPLC on an HC-C18 column (Agilent, 4.6 × 250 mm, 5 µm) with elution of MeOH/H2O (50:50), tR = 7.5 min (UV detection at 214-nm wavelength). C15H32N3O5P, mp 65–67 °C; [α]D20 = −36.2 (c = 0.7, H2O); IR (neat) 3503, 3211, 2921, 1714, 1658, 1121 cm−1; 1H NMR (600 MHz, D2O) δ 6.33 (1 H, d, JP-2 = 19.2 Hz), 4.23 (1 H, d, J = 9.4 Hz), 3.99 (1 H, dd, J = 10.2, 5.1 Hz), 3.86–3.84 (2 H, m), 3.53 (1 H, br s), 3.48–3.45 (1 H, m), 2.76–2.73 (1 H, m), 2.41–2.37 (1 H, m), 2.07 (3 H, s), 1.61–1.40 (4 H, m), 1.24 (3 H, t, J = 6.8 Hz), 0.89 (3 H, t, J = 7.1 Hz), 0.84 (3 H, t, J = 7.1 Hz); 13C NMR (150 MHz, D2O) δ 175.1, 136.4, 130.3 (C-1, d, JP-1 = 168 Hz), 84.2, 76.2, 76.1, 61.3, 53.6, 49.6, 29.9, 25.5, 25.2, 22.3, 15.8, 8.5; 31P NMR (242 MHz, D2O) δ 12.89; HRMS calcd for C15H28N2NaO5P [M + Na − NH4]+: 370.1639, found: m/z 370.1643.

Guanidino-tamiphosphor monoethyl ester (4c)

By a procedure similar to that for compound 3c, TPG diethyl ester 4b (2.73 g, 4 mmol) was treated with sodium ethanoate in ethanol, followed by work-up using Amberlite IR-120 and ion exchange with NH4HCO3, to give the ammonium salt of TPG monoethyl ester 4c (1.22 g, 75%) as white solids. The purity of product was >98% as shown by HPLC on an HC-C18 column (Agilent, 4.6 × 250 mm, 5 µm) with elution of MeOH/H2O (50:50), tR = 7.9 min (UV detection at 214-nm wavelength). C16H34N5O5P, mp 70–72 °C; [α]D20 = −11.5 (c = 0.6, H2O); IR (neat) 3521, 1931, 1756, 1623, 1210 cm−1; 1H NMR (600 MHz, D2O) δ 6.29 (1 H, d, JP-2 = 19.1 Hz), 4.25–4.22 (1 H, m), 3.91–3.82 (4 H, m), 3.51 (1 H, br s), 2.57–2.55 (1 H, m), 2.242.20 (1 H, m), 2.01 (3 H, s), 1.63–1.49 (3 H, m), 1.44–1.40 (1 H, m), 1.24 (3 H, t, J = 6.9 Hz), 0.88 (3 H, t, J = 7.0 Hz), 0.82 (3 H, t, J = 7.0 Hz); 13C NMR (150 MHz, D2O) δ 174.5, 160.3, 136.5, 131.8 (C-1, d, JP-1 = 171 Hz), 84.2, 76.9, 76.8, 61.2, 55.6, 51.0, 31.6, 25.6, 25.3, 22.0, 15.7, 8.5; HRMS calcd for C16H30N4NaO5P (M + Na − NH4)+: 412.1857, found: m/z 412.1859.

Viruses

Influenza A/WSN/33 (H1N1) viruses was obtained from Dr. Shin-Ru Shih (Chang Gung University in Taiwan) or from Dr. Kenneth Cochran (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor). A/Taiwan/3446/2002 (H3N2) and B/Taiwan/70641/2004 were gifts from Dr. Shin-Ru Shih (Chang Gung University in Taiwan). The reassortant H5N1 virus NIBRG14 created with hemagglutinin as well as neuraminidase genes from A/Vietnam/1194/2004 and the other genes from PR8 were originally from National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (Hertfordshire, UK). Influenza A/California/07/2009 (H1N1, Pandemic), A/Brisbane/10/2007 (H3N2), A/Udorn/1972 (H3N2) were obtained from Centers for Disease Control (Taiwan). The oseltamivir-resistant A/WSN H275Y mutant was created using 12-plasmid system that is based on co-transfection of mammalian cells with 8 plasmids encoding virion sense RNA under the control of a human PolI promoter and 4 plasmids encoding messenger RNA encoding the RNP complex (PB1, PB2, PA and nucleoprotein gene products) under the control of a PolII promoter.32,33 An H275Y mutation was introduced in the NA gene and the sequence was confirmed to generate the A/WSN H275Y virus. Alternatively, the oseltamivir-resistant WSN mutant was selected by 6 passages in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells with gradually increased OC (oseltamivir carboxylate) concentrations. This mutant influenza grows well in the presence of 1 µM OC and carries a single H275Y mutation at its NA gene confirmed by sequence analysis. Influenza A/Panama/2007/99 (H3N2), A/Hong Kong/2369/2009 (H275Y, oseltamivir-resistant H1N1), B/Florida/4/2006 and B/Sichuan/379/99 viruses were obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA., USA). Influenza A/Victoria/3/75 (H3N2) virus was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Mouse adapted influenza A/California/04/2009 (H1N1) and A/Duck/MN/1525/81 were kindly provided by Drs. Elena Govorkova and Robert Webster (St Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN), respectively. All viruses were cultured in the allantoic cavities of 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs for 72 h, and purified by sucrose gradient centrifugation. In another preparation, A/California/04/2009 (H1N1) virus was adapted to replication in the lungs of BALB/c mice by 9 sequential passages through mouse lungs. Virus was plaque purified in MDCK cells and a virus stock was prepared by growth in embryonated chicken eggs and then MDCK cells.

Determination of influenza virus TCID50

MDCK cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA), and were grown in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin-streptomycin at 37 °C under 5% CO2. The TCID50 (50% tissue culture infectious dose) was determined by incubation of serially diluted influenza virus in 100 µL solution with 100 µL MDCK cells at 1 × 105 cells/mL in 96-well microplates. The infected cells were incubated at 37 °C under 5% CO2 for 48–72 h and added to each wells with 100 µL per well of CellTiter 96® AQueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay reagent (Promega). After incubation at 37 °C for 15 min, absorbance at 490 nm was read on a plate reader. Influenza virus TCID50 was determined using Reed–Muench method.34,35

Determination of IC50 of neuraminidase inhibitors

The neuraminidase activity was measured using either fluorogenic or luminescence substrate. In one approach, the neuraminidase activity was measured using diluted allantoic fluid harvested from influenza virus infected embryonated eggs and a fluorogenic substrate 2'-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-α-d-N-acetylneuraminic acid (MUNANA; Sigma). For inhibition test, the compound of interest was incubated with diluted virus-infected allantoic fluid for 10 min at room temperature followed by the addition of 200 µM of substrate. The fluorescence of the released 4-methylumbelliferone was measured in Envision plate reader (Perkin-Elmer, Wellesley, MA) using excitation and emission wavelengths of 365 and 460 nm, respectively. Inhibitor IC50 value were determined from the dose-response curves by plotting the percent inhibition of NA activity versus inhibitor concentrations using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

Alternatively, the effect of inhibitor on viral NA activity was performed using a commercially available kit with a chemiluminescent substrate of sialic acid 1,2-dioxetane derivative (NA-Star® Influenza Neuraminidase Inhibitor Resistance Detection Kit, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in 96-well solid white microplates following the manufacturer’s instructions. Inhibitor in half-log dilution increments was incubated with virus (as the source of neuraminidase). The amount of virus in each microwell was approximately 500 cell culture infectious doses (CCID50). Plates were pre-incubated for 10 min at 37 °C prior to addition of chemiluminescent substrate. Following addition of substrate, plates were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The NA activity was evaluated using a Centro LB 960 luminometer (Berthold Technologies) for 0.5 sec immediately after addition of NA-Star® accelerator solution. Fifty percent inhibitory concentrations (IC50 values) of viral NA activity were determined by plotting percent chemiluminescent counts versus log10 of the concentration of inhibitor.

Determination of EC50 of neuraminidase inhibitors

The anti-influenza virus activities of NA inhibitors were measured by the EC50 values, i.e. the concentrations of the compound required for 50% protection of the influenza virus infection-mediated cytopathic effects (CPE). Fifty to 100 µL of diluted influenza virus (100 TCID50) were mixed with equal volumes of NA inhibitors at varied concentrations. The mixtures were then used to infect 100 µL of MDCK cells at 1 × 105 cells/mL in 96-wells. After 48–72 h incubation at 37 °C under 5% CO2, the CPE were determined with CellTiter 96® AQueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay reagent as described above, or alternatively with 0.11 final percentage of neutral red for 2 h. Inhibitor EC50 value were determined by fitting the curve of percent CPE versus the concentrations of NA inhibitor using Graph Pad Prism 4.

Animal experiments for virus challenges

Female BALB/c mice (18–20 g) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories or National Laboratory Animal Center (Taiwan). The mice were quarantined for 48–72 h before use. The mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of zoletil (or ketamine/xylazine) and inoculated intranasally with 25 µL of infectious influenza virus. The test compounds were dissolved in sterile water, and administered to mice at the indicated dosages by oral gavage (p.o.) twice daily for 5 days. Control mice received sterile water on the same schedule. Ten mice per test group were used throughout the studies. Four hours after the first dose of drug, mice were inoculated with influenza virus at 3–10 mouse LD50, depending upon the virus strain. Mice were observed daily for 14–21 days for survival and body weight.

Statistical analysis

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated and compared by the Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test using Prism 5.0b (GraphPad Software Inc.). Where statistical significance was seen, pairwise comparisons were made by the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test. Mean body weights were analyzed by ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test using Prism 5.0b. For stability studies in gastric fluid, fresh human liver microsomes, and pharmacokinetic study with compound in normal saline, the Microsoft® Excel 2002 (e.g. Mean, SD, % CV, % Diff) and SPSS 13.0 software (ANOVA and linear regression) were used.

Ethical regulation of laboratory animals

This study was conducted in accordance with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Utah State University dated 20 September, 2010 (expires Sept. 19, 2013), or the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, National Defense Medical Center, Taiwan (2009–2011), or the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Academia Sinica, Taiwan. The work was done in the AAALAC-accredited Laboratory Animal Research Center of Utah State University, or in the AAALAC-accredited Animal Center of National Defense Medical Center, or in the BSL-3 Laboratory of Genomics Research Center, Academia Sinica, Taiwan. The U. S. Government (National Institutes of Health) approval was renewed on April 7, 2010 (Animal Welfare Assurance no. A3801-01) in accordance to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Revision; 2010).36

Determination of octanol–buffer partition coefficients

The standard solutions of compound in MeOH at various concentrations of 1.0, 0.5, 0.1, 0.05 and 0.01 (mg/mL) were measured by HPLC (Agilent 1100 series) on an HC-C18 column (5 µm porosity, 4.6 × 250 mm) using MeOH/H2O (1:1) as the eluent and UV detector at λ = 214 nm. The integral area of the peak corresponding to the compound was used (average of triple experiments) to establish standard curve by Microsoft Excel.

To test compound partitioning, the respective test compounds (~1.0 mg) were placed in Eppendorf tube, and octanol (0.75 mL) and phosphate buffer saline (0.75 mL of 0.01 M solution, pH 7.4) were added. The solution was equilibrated at 37 °C using magnetic stirring at 1200 rpm for 24 hours. The octanol and aqueous phases were then separated by centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 5 min. Each sample (25 µL) of aqueous layer was measured by HPLC. The concentration of drug in the aqueous phase was deduced by calibration with the above-established standard curve. Five replicates of each determination were carried out to assess reproducibility. From these data, the apparent octanol/buffer (pH 7.4) partition coefficient, DB = [Bt]oct / [Bt]aq, is determined, where [Bt]oct and [Bt]aq are the concentrations of the drug in organic and aqueous phases, respectively.

LC/MS/MS determination

Samples were separated with a Shimadzu liquid chromatograph separation system equipped with degasser DGU-20A3, solvent delivery unit LC-20AD, system controller CBM-20A, column oven CTO-10ASVP and CTC Analytics HTC PAL System. The samples (10 µL) were separated on a pre-guarded Phenomenex Luna C18 column (5 µ, 2.0 × 50 mm) with acetonitrile (A) and water (B) (both containing 0.1% formic acid) in a sequence of A/B 1:9 (0–2 min), 1:0 (2–2.3 min), and 1:9 (2.3–3.5 min) at 25 °C with an elution rate of 600 µL/min.

For stability studies in gastric fluid and fresh human liver microsomes, and for pharmacokinetic studies with compounds in normal saline, the respective samples of rat plasma (100 µL), mouse plasma (10 µL) and microsomes (200 µL) were chromatographically separated with a pre-guarded Waters Atlantis® T3 3µ C18 (2.1 × 100 mm) column. The mobile phase was CH3CN/H2O/HCO2H (40:60:0.1, v/v/v).

Mass spectrometric analysis was performed using an API 3000 LC-MS/MS from Applied Biosystems Inc. (Canada) with an electrospray ionization (ESI) interface. Ionization was conducted in the positive mode and ion source temperature was maintained at 400 °C. High purity nitrogen gas was used as the collision-induced dissociation (CAD) gas, curtain gas, and nebulizer gas. Positive multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode was used for the quantification. The selected transitions of m/z were 321.1 [M + H]+ → 174.2 [M – pentyloxy – acetamide]+ for compound 3a (collision energy, 31 eV), 349.3 [M + H]+ → 261.2 [M – pentyloxy]+ for compound 3c (collision energy, 20 eV), 363.4 [M + H]+ → 216.1 [M – pentyloxy – acetamide]+ for compound 4a (collision energy, 32 eV) and 391.3 [M + H]+ →303.3 [M – pentyloxy]+ for compound 4c (collision energy, 27 eV).

Stability of compound in simulated gastric fluid

In order to determine whether the test compound is likely to be stable in the stomach, a simulated gastric fluid (SGF, without enzymes) was prepared by dissolving 2 g NaCl in 1 L ddH2O and adjusted pH to 1.2 with HCl.37 The test compound was incubated at a concentration of 2.5 mg/mL in the presence or absence of simulated gastric fluid for 30 min at room temperature. After 30 min, the samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 13,000 g and the supernatant was transferred to a plate for LC/MS/MS analysis. The experiment was performed in triplicates.

Metabolic stability of compound in whole blood and microsomes

Human, dog, and rat whole blood samples were obtained from normal healthy individuals. Stock solutions of test compounds were prepared in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) at the concentration of 1 mM, and diluted to a final concentration of 500 µM. Test compounds were incubated with whole blood at a final concentration of 5 µM at 37 °C at 100 rpm on an orbital shaker. Aliquots were removed at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60 and 120 min, and the reaction was stopped by the addition of 5 volumes of cold methanol. After centrifugation at 20,000 g for 20 min to precipitate protein, an aliquot of 200 µL from the supernatant was used for LC/MS/MS analysis. All experiments were performed in duplicates.

Human, male dog, and male rat pooled liver microsomes were purchased from BD Biosciences and stored at −80 °C prior to use. A master solution containing 250 µg microsomes in 5.6 mM phosphate buffer and 5.6 mM MgCl2 was prepared and mixed with test compounds or control solution (testosterone and midazolam) at the final concentration of 3 µM. The mixture was pre-warmed at 37 °C for 2 min, and then the reaction was started at 37 °C with the addition of 50 µL of ultrapure H2O (for negative control) or 10 mM NADPH solution at the final concentration of 1 mM. Aliquots of 50 µL were removed from the reaction at 0, 10, 20, 30 and 60 min, and stopped by the addition of 3 volumes of cold methanol. After centrifugation at 16,000 rpm for 10 min, an aliquot (100 µL) of the supernatant was collected for LC/MS/MS analysis. All experiments were performed in duplicate. All calculations were carried out using Microsoft Excel 2003. The slope value, k, was determined by linear regression of the natural logarithm of the peak area of the parent drug vs. incubation time curve. Peak areas were determined from extracted ion chromatograms. The in vitro half-life (in vitro t1/2) was determined from the slope value: in vitro t1/2 = −(0.693/k). Conversion of the in vitro t1/2 (in min) into the in vitro intrinsic clearance (in vitro CLint, in µL/min/mg proteins) was done using the following equation (mean of duplicate determinations):

in vitro CLint = (0.693/t1/2) × [volume of incubation (µL) / amount of proteins (mg)]

Other metabolic stability studies were conducted in five pooled fresh human liver microsomes. An incubation mixture containing test compound (80 ng/mL), phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH = 7.4), MgCl2 (5 mM) and NADPH regenerating solution (1 mM NADP+, 10 mM G6P, and 2 IU G6PD) or UDPGA (2 mM) was vortexed well. The reaction mixture, in a final volume of 500 µL, was pre-incubated for 1 min at 37 °C, and the human liver microsomes (0.5 mg/mL),38 freshly prepared from five human livers obtained from the Department of Surgery, Tri-Service General Hospital (Taipei, Taiwan), were added to start the reaction. Each reaction was stopped at 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45 and 60 min by adding 500 µL of cold acetonitrile. After termination of the incubation, oseltamivir (50 µL, 40 ng/mL) was added as an internal standard for analysis. The sample was centrifuged, and 200 µL aliquot was taken and evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure. The dried sample was reconstituted with 50% methanol for LC/MS/MS analysis. All experiments were performed in triplicates.

Pharmacokinetic studies in rats with compounds in normal saline

All four compounds were administered as aqueous solutions in normal saline. Male rats were purchased from BioLASCO Taiwan Co., Ltd. The test compound was administered to six Sprague-Dawley rats (250–350 g) as a single intravenous (i.v.) dose (0.3–1 mg/kg of body weight) or as a single oral dose (1–5 mg/kg). At predetermined time points up to 24 h postdosing, blood samples were collected via a tail lateral vein, placed into heparinized tubes, and processed to extract the plasma, which was then stored at −20 °C. As an example of a representative sampling schedule, plasma samples were collected at 0.08, 0.17, 0.33, 0.67, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16 and 24 h after administration of the i.v. dose to the rats and at 0.08, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 h after administration of the oral dose to the rats. The samples were extracted by Oasis® MCX cartridge. The concentrations of compounds in the eluate were determined by LC/MS/MS analysis.

Pharmacokinetic studies in mice with compounds in normal saline

The compounds were administered as aqueous solutions in normal saline. Male mice were purchased from BioLASCO Taiwan Co., Ltd. The compounds were administered to six mice as a single i.v. dose (0.25 mg/kg of body weight) or as a single oral dose (10 mg/kg). Plasma were prepared from tail lateral vein bleeds at 0.17, 0.33, 0.67, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 24 h, and then stored at −20 °C. Deproteinized plasma samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 13,000 g and the supernatant was transferred to a plate for LC/MS/MS analysis. The concentrations of compound in the mice plasma samples were determined by LC/MS/MS analysis.

Pharmacokinetic studies in rats and dogs with compound dissolved in 20% HP-β-CD in water or in microcrystalline cellulose

Compound 4c was prepared as aqueous solution in 20% 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HP-β-CD) in water or in microcrystalline cellulose. The sample of 4c was administered to rats or dogs as a single i.v. dose (2 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg of body weight in rats and dogs, respectively) or as a single oral dose (50 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg in rats and dogs, respectively). Plasma samples were collected at 0.08, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8 and 24 h after administration of the i.v. dose and at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8 and 24 h after administration of the oral dose. The concentrations of test compound in the rat and dog plasma samples were determined by LC/MS/MS analysis.

Pharmacokinetic analysis

The pharmacokinetic parameters were obtained using a pharmacokinetic program WinNonlin, fitting data to a noncompartmental model. The pharmacokinetic parameters including the area under the plasma concentration-versus-time curve (AUC) to the last sampling time, (AUC0–t), to the time infinity (AUC0–∞), the terminal-phase half-life (t1/2), the maximum concentration of compound in plasma (Cmax), the time of Cmax (Tmax), the mean residence time (MRT), and the first order rate constant associated with the terminal portion of the curve (k) were estimated via linear regression of time vs. log concentration. The total plasma clearance (CL) was calculated as dose/AUCi.v, and the apparent volume of distribution (Vd) of drug administered i.v. was calculated as CL × k. The oral bioavailability (F) of the test compound by oral administration was calculated from the AUC0–∞ of the oral dose divided by the AUC0–∞ of the i.v. dose.

Protein binding study

Plasma protein binding was determined using rapid equilibrium dialysis method.39 Test compounds were prepared in DMSO at the concentration of 1 mM and diluted in series in 50% DMSO/H2O. Human, rat or dog plasma was then spiked with the compound(s) at a final concentration of 1 µM with the final concentration of DMSO less than 1%. All compounds were tested in duplicates. Ranitidine and testosterone were included as the control compounds. A rapid equilibrium dialysis device in 96-well format with dialysis membrane of 8,000 dalton cut-off (Pierce) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the base plate was rinsed with 20% ethanol for 10 min, followed by two rinses with ultra pure water. The base plate was then air-dried and used immediately. After the inserts were placed open end up into the wells of the base plate, 300 µL of phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) was added to the buffer chamber and 100 µL of spiked plasma sample was added into the sample chamber (indicated by a red ring). The device was then covered with a sealing tape and incubated at 37 °C at approximately 100 rpm on an orbital shaker for 4 h. An aliquot of 50 µL from both buffer and plasma chambers were collected into separate micro-centrifuge tubes. Fifty µL of plasma was added to the aliquot from the buffer chamber while 50 µL of PBS to the collected plasma samples. Three-hundred µL of MeOH was then added to precipitate protein and release compound(s). After vortexed and incubated for 30 min, the samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 16,000 g and the supernatant was transferred to a plate for LC/MS/MS analysis.

All calculations were carried out using Microsoft Excel 2003. The concentrations of test compounds in the buffer and plasma chambers were derived from the integrated area of the corresponding peak with known concentrations of the compounds as standards. The percentages of the bound fraction of the test compounds were calculated by the following equation:

% Free = (concentration in buffer chamber / concentration in plasma chamber) × 100%

% Bound = 100% − % Free

Excretion study of compound 4c

A single oral dose (5 mg/kg) of compound 4c was administered by gavage to six SD rats (average weight, 270 g). The rats were kept in metabolic cages and their urine and feces were collected at 4, 8, 12, 24 and 48 h. The contents of compounds were determined by LC/MS/MS analysis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Academia Sinica, the National Science Council of Taiwan (grant NSC-98-2321-B-001-022), National Institute of Health of United States (NIH contract N01-AI-30063 to E.B.T.), and TaiMed Biologics for financial supports, as well as Dr. Donald F. Smee (Utah State University) and Mr. Shi-Chiang Li (National Defense Medical Center) for technical supports.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- AUC

area under the concentration-versus-time curve

- CL

clearance

- CPE

cytopathic effect

- CYP

cytochrome P 450

- D

distribution coefficient

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium

- EC50

half maximal effective concentration

- F (%)

oral bioavailability (fraction absorbed)

- GOC

guanidino-oseltamivir carboxylic acid

- GOS

guanidino-oseltamivir

- HP-β-CD

2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- IC50

half maximal inhibitory concentration

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- i.v.

intravenous

- LD50

median leathal dose

- MS

mass spectrometry

- MDCK

Madin–Darby canine kidney

- MRT

the mean residence time

- NA

neuraminidase

- OC

oseltamivir carboxylic acid

- OS

oseltamivir

- P

partition coefficient

- SGF

simulated gastric fluid

- TCID50

50% cell culture infectious dose

- TP

tamiphosphor

- TP1Et

tamiphosphor monoethyl ester

- TP2Et

tamiphosphor diethyl ester

- TPG

guanidino-tamiphosphor

- TPG1Et

guanidino-tamiphosphor monoethyl ester

- TPG2Et

guanidino-tamiphosphor diethyl ester

- UDPGA

uridine 5′-diphosphoglucuronic acid

- UGT

uridine 5'-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase

- ZA

zanamivir

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Supplementary Figures, Tables, and NMR spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schmidt AC. Antiviral therapy for influenza: a clinical and economic comparative review. Drugs. 2004;64:2031–2046. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464180-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moscona A. Neuraminidase inhibitors for influenza. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:1363–1373. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Clercq E. Antiviral agents active against influenza A viruses. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;5:1015–1025. doi: 10.1038/nrd2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woods JM, Bethell RC, Coates JA, Healy N, Hiscox SA, Pearson BA, Ryan DM, Ticehurst J, Tilling J, Walcott SM. 4-Guanidino-2,4-dideoxy-2,3-dehydro-N-acetylneuraminic acid is a highly effective inhibitor both of the sialidase (neuraminidase) and of growth of a wide range of influenza A and B viruses in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1473–1479. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.7.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunn CJ, Goa KL. Zanamivir: a review of its use in influenza. Drugs. 1999;58:761–784. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199958040-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim CU, Lew W, Williams MA, Wu H, Zhang L, Chen X, Escarpe PA, Mendel DB, Laver WG, Stevens RC. Structure-activity relationship studies of novel carbocyclic influenza neuraminidase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:2451–2460. doi: 10.1021/jm980162u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McClellan K, Perry CM. Oseltamivir: a review of its use in influenza. Drugs. 2001;61:263–283. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161020-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sidwell RW, Smee DF. Peramivir (BCX-1812, RWJ-270201): potential new therapy for influenza. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs. 2002;11:859–869. doi: 10.1517/13543784.11.6.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain S, Fry AM. Peramivir: another tool for influenza treatment? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52:707–709. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kubo S, Tomozawa T, Kakuta M, Tokumitsu A, Yamashita M. Laninamivir prodrug CS-8958, a long-acting neuraminidase inhibitor, shows superior anti-influenza virus activity after a single administration. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1256–1264. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01311-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikematsu H, Kawai N. Laninamivir octanoate: a new long-acting neuraminidase inhibitor for the treatment of influenza. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2011;9:851–857. doi: 10.1586/eri.11.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shie J-J, Fang J-M, Wang S-Y, Tsai K-C, Cheng Y-SE, Yang A-S, Hsiao S-C, Su C-Y, Wong C-H. Synthesis of tamiflu and its phosphonate congeners possessing potent anti-influenza activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:11892–11893. doi: 10.1021/ja073992i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shie J-J, Fang J-M, Wong C-H. A concise and flexible synthesis of the potent anti-influenza agents tamiflu and tamiphosphor. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:5788–5791. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Itzstein M, Wu W-Y, Kok GB, Pegg MS, Dyason JC, Jin B, Phan TV, Smythe ML, White HF, Oliver SW, Colman PM, Varghese JN, Ryan DM, Woods JM, Bethell RC, Hotham VJ, Cameron JM, Penn CR. Rational design of potent sialidase-based inhibitors of influenza virus replication. Nature. 1993;363:418–423. doi: 10.1038/363418a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White CL, Janakiraman MN, Laver GW, Philippon C, Vasella A, Air GM, Luo M. A sialic acid-derived phosphonate analog inhibits different strains of influenza virus neuraminidase with different efficiencies. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;245:623–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carbain B, Martin SR, Collins PJ, Hitchcock PB, Streicher H. Galactose-conjugates of the oseltamivir pharmacophore – new tools for the characterization of influenza virus neuraminidases. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009;7:2570–2575. doi: 10.1039/b903394g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demmer CS, Krogsgaard-Larsen N, Bunch L. Review on modern advances of chemical methods for the introduction of a phosphonic acid group. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:7981–8006. doi: 10.1021/cr2002646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schug KA, Lindner W. Noncovalent binding between guanidinium and anionic groups: focus on biological- and synthetic-based arginine/guanidinium interactions with phosph[on]ate and sulf[on]ate residues. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:67–114. doi: 10.1021/cr040603j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Proudfoot JR. The evolution of synthetic oral drug properties. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:1087–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Straub JO. An environmental risk assessment for oseltamivir (Tamiflu®) for sewage works and surface waters under seasonal-influenza- and pandemic-use conditions. Ecotox. Environ. Safety. 2009;72:1625. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller JM, Dahan A, Gupta D, Varghese S, Amidon GL. Enabling the intestinal absorption of highly polar antiviral agents: Ion-pair facilitated membrane permeation of zanamivir heptyl ester and guanidino oseltamivir. Mol. Pharmaceutics. 2010;7:1223–1234. doi: 10.1021/mp100050d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu K-C, Lee P-S, Wang S-Y, Cheng Y-SE, Fang J-M, Wong C-H. Intramolecular ion-pair prodrugs of zanamivir and guanidino-oseltamivir. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011;19:4796–4802. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.06.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li W, Escarpe PA, Eisenberg EJ, Cundy KC, Sweet C, Jakeman KJ, Merson J, Lew W, Williams M, Zhang L, Kim CU, Bischofberger N, Chen MS, Mendel DB. Identification of GS4104 as an orally bioavilable prodrug of the influenza virus neuraminidase inhibitor GS4071. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998;42:647–653. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.3.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koyama K, Takahashi M, Oitate M, Nakai N, Takakusa H, Miura S-i, Okazaki O. CS-8958, a prodrug of the novel neuraminidase inhibitor R-125489, demonstrates a favorable long-retention profile in the mouse respiratory tract. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4845–4851. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00731-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie G, Nie T, Mackenzie GG, Sun Y, Huang L, Ouyang N, Alsont N, Zhu C, Murray OT, Constantinides PP, Kopelovich L, Rigas B. The metabolism and pharmacokinetics of phospho-sulindac (OXT-328) and the effect of difluoromethylornithine. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012;165:2152–2166. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01705.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Widmer N, Meylan P, Ivanyuk A, Aouri M, Decosterd LA, Buclin T. Oseltamivir in seasonal, avian H5N1 and pandemic 2009 A/H1N1 influenza: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2010;49:741–765. doi: 10.2165/11534730-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cass LM, Efthymiopoulos C, Bye A. Pharmacokinetics of zanamivir after intravenous, oral, inhaled, or intranasal administration to healthy volunteers. Clin. Pharmacol. 1999;36(Suppl):1–11. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199936001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krise JP, Stella VJ. Prodrugs of phosphates, phosphonates, and phosphinates. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1996;19:287–310. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun J, Miller JM, Beig A, Rozen L, Amidon GL, Dahan A. Mechanistic enhancement of the intestinal absorption of drugs containing the polar guanidino functionality. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2011;7:313–323. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2011.550875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boonyapiwat B, Sarisuta N, Kunastitchai S. Characterization and in vitro evaluation of intestinal absorption of liposomes encapsulating zanamivir. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2011;8:392–397. doi: 10.2174/156720111795767915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Varghese Gupta S, Gupta D, Sun J, Dahan A, Tsume Y, Hilfinger J, Lee K-D, Amidon GL. Enhancing the intestinal membrane permeability of zanamivir: a carrier mediated prodrug approach. Mol. Pharmaceutics. 2011;8:2358–2367. doi: 10.1021/mp200291x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neumann G, Watanabe T, Ito H, Watanabe S, Goto H, Gao P, Hughes M, Perez DR, Donis R, Hoffmann E, Hobom G, Kawaoka Y. Generation of influenza A viruses entirely from cloned cDNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:9345–9350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fodor E, Devenish L, Engelhardt OG, Palese P, Brownlee GG, García-Sastre A. Rescue of influenza A virus from recombinant DNA. J. Virol. 1999;73:9679–9682. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9679-9682.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reed LJ, Müench H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burleson FG, Chambers TM, Wiedbrauk DL. Virology, a Laboratory Manual. San Diego, CA, USA: Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Research Council. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Washington, DC, USA: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 37.United States Pharmacopeia and National Formulary. 34th Ed. Rockville, MD, USA: United States Pharmacopeial Convention Inc.; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 38. [Last accessed 6 October 2006];Guidance for Industry: Drug interaction studies: study design, data analysis and implications for dosing and labeling. http://www.fda.gov/cder Draft published in September 2006.

- 39.Waters NJ, Jones R, Williams G, Sohal B. Validation of a rapid equilibrium dialysis approach for the measurement of plasma protein binding. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008;97:4586–4595. doi: 10.1002/jps.21317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.