Abstract

NADP-malic enzyme (NADP-ME, EC 1.1.1.40), a key enzyme in C4 photosynthesis, provides CO2 to the bundle-sheath chloroplasts, where it is fixed by ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. We characterized the isoform pattern of NADP-ME in different photosynthetic species of Flaveria (C3, C3-C4 intermediate, C4-like, C4) based on sucrose density gradient centrifugation and isoelectric focusing of the native protein, western-blot analysis of the denatured protein, and in situ immunolocalization with antibody against the 62-kD C4 isoform of maize. A 72-kD isoform, present to varying degrees in all species examined, is predominant in leaves of C3 Flaveria spp. and is also present in stem and root tissue. By immunolabeling, NADP-ME was found to be mostly localized in the upper palisade mesophyll chloroplasts of C3 photosynthetic tissue. Two other isoforms of the enzyme, with molecular masses of 62 and 64 kD, occur in leaves of certain intermediates having C4 cycle activity. The 62-kD isoform, which is the predominant highly active form in the C4 species, is localized in bundle-sheath chloroplasts. Among Flaveria spp. there is a 72-kD constitutive form, a 64-kD form that may have appeared during evolution of C4 metabolism, and a 62-kD form that is necessary for the complete functioning of C4 photosynthesis.

Most land plants use the C3 pathway for carbon fixation, in which each photosynthetic cell uses Rubisco to fix CO2 directly into C-3 compounds. In C4 plants, fully differentiated mesophyll and bundle-sheath cells cooperate to fix CO2 by the C4 pathway (Edwards and Walker, 1983; Hatch, 1987). In these plants, atmospheric CO2 is first incorporated into C-4 acids in the mesophyll cells, which are then transported to bundle-sheath cells, where they are decarboxylated and the released CO2 is incorporated into organic phosphate by the C3 cycle. The C4 system is more efficient under some environmental conditions due to CO2 being concentrated in bundle-sheath cells that suppresses the oxygenase activity of Rubisco and, thus, photorespiration. C3-C4 intermediate species are thought to represent a stage in the evolutionary transition from the C3 photosynthetic mechanism to C4 photosynthesis (Monson et al., 1984; Raws-thorne, 1992). In C3-C4 species, two mechanisms are proposed to account for the low apparent photorespiration (Monson et al., 1984; Rawsthorne, 1992). In all intermediates, Rubisco is found in both mesophyll and bundle-sheath cells. The mesophyll cells function as in C3 plants in the fixation of atmospheric CO2 by RuBP carboxylase via the C3 pathway, and in the RuBP oxygenase reaction, which is the first step in generating C-2 compounds for the photosynthetic oxidation cycle. In one mechanism of reducing photorespiration that may be common to all intermediates, photorespiratory metabolites generated as a consequence of the RuBP oxygenase reaction in mesophyll cells, glycolate and Gly, are transported to bundle-sheath cells, metabolized through mitochondrial Gly decarboxylase, and the CO2 released is refixed by Rubisco in bundle-sheath chloroplasts. Through this means, reduced photorespiratory CO2 evolution occurs without the operation of a C4 cycle. In some intermediates, the operation of a limited C4 cycle between the mesophyll and bundle-sheath cells contributes to the further reduction of photorespiration. These plants exhibit elevated activities and partial cellular compartmentation of key enzymes of C4 photosynthesis.

The genus Flaveria contains not only C3 and C4 species, but also a number of C3-C4 intermediates that have different capacities to reduce photorespiration by the above mechanisms (Ku et al., 1991). The C4 Flaveria spp. have been classified as the NADP-ME subtype, since this is the major enzyme for decarboxylation of C4 acids (Ku et al., 1983). Full-length cDNA clones encoding the enzyme have been isolated from the C4 species Flaveria trinervia (Borsch and Westhoff, 1990) and the C3 species Flaveria pringlei (Lipka et al., 1994). Both cDNA clones encode proteins of 71 kD in size, which contain 7.9-kD putative transit peptide sequences for chloroplast targeting of the preproteins. The size of both mature proteins is about 62 kD. In addition, a partial cDNA clone has been reported for the C3-C4 intermediate Flaveria linearis (Rajeevan et al., 1991). Lipka et al. (1994) concluded that the gene encoding the C4 NADP-ME isoform descended from a common ancestral gene already present in C3 species. More recently, Marshall et al. (1996) isolated three genomic clones of NADP-ME from the C4 species Flaveria bidentis and concluded from Southern-blot analysis and sequence comparison with NADP-ME cDNA clones from other plants that Flaveria spp. contain three and possibly four NADP-ME genes. They proposed that the NADP-ME gene family is more complex than previously thought; the two genomic clones characterized encode two highly similar forms of the enzyme, one being expressed in C4 photosynthetic tissue (Me1), whereas the other (Me2) appears to be constitutively expressed. Genomic Southern blotting with gene-specific probes showed that both Me1 and Me2 are found in C3 and C4 Flaveria spp., and it was suggested that the genes may have arisen by gene duplication in a common ancestral species. The sizes of proteins encoded by these two genes have not been determined (W.C. Taylor, personal communication). Since some evidence exists for a multigene family for NADP-ME in Flaveria spp., it is important to evaluate the presence of different isoforms that are produced in different photosynthetic types of Flaveria at the protein level, and their tissue- and cell-specific localization. In the present study we detected three isoforms of the enzyme in various Flaveria spp. One of them, a 72-kD monomer, is found to be constitutively expressed in photosynthetic and nonphotosynthetic tissues of the different photosynthetic types examined, whereas two other isoforms, 64- and 62-kD monomers, are only abundant in photosynthetic tissue having partial or complete C4 photosynthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The species used in the study were Flaveria pringlei, Flaveria robusta, and Flaveria cronquistii (C3); Flaveria sonorensis, Flaveria oppositifolia, Flaveria angustifolia, Flaveria linearis, Flaveria floridana, and Flaveria ramosissima (C3-C4); Flaveria brownii and Flaveria vaginata (C4-like); and Flaveria bidentis and Flaveria trinervia (C4). The species were propagated vegetatively from shoot cuttings or germinated from seeds and grown in a compost:sand:perlite mixture (2:1:1, v/v). The plants were grown in a greenhouse at a 25/18°C day/night thermoperiod and a 13- to 16-h photoperiod. Maximum illumination on a clear day during the summer months provided a PPFD of 1750 μmol m−2 s−1. Supplemental light from metal-halide lamps provided a PPFD of 350 μmol m−2 s−1 on cloudy days. Plants were fertilized twice per week with Peter's fertilizer supplemented with micronutrients. The third and fourth pairs of leaves from the apex were used for protein preparations.

Extraction and Assay of NADP-ME

For assay of NADP-ME activity, leaves were excised during the middle of the light period, immediately plunged into liquid nitrogen, and ground to a fine powder using a chilled mortar and pestle. Extraction medium (50 mm Hepes-KOH, pH 7.5, 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm MnCl2, 5 mm DTT, 2 mm PMSF, and 2% [w/v] insoluble PVP) was added (10 mL g−1 fresh weight) and grinding was continued until total maceration. Crude extracts were filtered through a layer of Miracloth (Calbiochem) and centrifuged at 15,000g for 5 min. The supernatant fluid was immediately desalted through a Sephadex G-25 column pre-equilibrated with the extraction medium without PVP. The desalted extracts were used for enzyme assay. NADP-ME was assayed spectrophotometrically at 30°C in a mixture containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 2.5 mm DTT, 20 mm MgCl2, 0.4 mm NADP, and 25 to 50 μL of enzyme extract. The reaction was initiated by adding 5 mm malate (pH 7.8), and the increase in A340 was recorded.

Suc Density Gradient Centrifugation

For experiments using Suc density centrifugation, leaf protein was extracted from F. cronquistii (9 g), F. brownii (5 g), F. ramosissima, and F. trinervia (both 2 g) as described above. Clarified extracts were obtained by centrifugation at 15,000g for 1 h. The supernatant fraction was brought to 80% saturation with ammonium sulfate at 4°C, stirred for 1 h, and recentrifuged for 15 min. The pellet was resuspended in 2 mL of extraction buffer without PVP and centrifuged at 15,000g for 10 min. The supernatant fluid was diluted with an equal volume of extraction buffer (minus PVP), and 2 mL was loaded onto a 35-mL 10 to 30% (w/v) linear Suc density gradient. The Suc gradient was prepared from 10 and 30% (w/v) stock solutions containing 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5 mm DTT, 2.5 mm MgCl2, and 0.2 mm EDTA. The gradients were centrifuged at 110,000g for 40 h, and after centrifugation 1-mL fractions were collected and assayed for NADP-ME activity. Peak fractions were pooled for kinetic studies. Suc concentrations were determined using a refractometer.

IEF and Activity Staining

For IEF analysis of NADP-ME, leaf protein samples were prepared by grinding the tissue in 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm MgCl2, 10 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 2 mm PMSF. Nondenaturing IEF was performed using a 5% (w/v) acrylamide gel with a pH range from 5.0 to 7.0 (samples were loaded on the surface of the gel using small pieces of filter paper). The gels were run for 3 h at 6°C (constant voltage of 0.6 kV) in a LKB 2117 Multiphor system. The pH gradient on the gels was determined by employing a surface pH electrode. NADP-ME on the gels was detected by incubating in a solution containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mm l-malate, 10 mg of MgCl2, 0.5 mm NADP, 0.1 mg mL−1 nitroblue tetrazolium, and 5 μg mL−1 phenazine methosulfate at room temperature.

SDS-PAGE and Immunoblotting

For western immunoblot studies, total protein from the different tissues was extracted using a phenol extraction procedure according to the work of van Etten et al. (1979). The extraction buffer contained 0.7 m Suc, 0.5 m Tris, 30 mm HCl, 50 mm EDTA, 0.1 m KCl, 2% (v/v) 2-mercaptoethanol, 10% (w/v) insoluble PVP, 2 mm PMSF, and 10 μm leupeptin. After total maceration in extraction buffer, an equal volume of water-saturated phenol was added and mixed. Protein that partitioned to the phenol phase was separated from the aqueous phase by centrifugation and precipitated by methanol. Protein was dissolved in 0.25 m Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 2% (w/v) SDS, 0.5% (v/v) 2-mercaptoethanol and boiled for 2 min prior to being loaded onto the gel.

For analysis of protein samples by western blotting, 7.5 to 15% (w/v) linear gradient polyacrylamide gels containing SDS were used. After electrophoretic separation, proteins on the gels were electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane for immunoblotting according to the work of Burnette (1981). Anti-maize 62-kD NADP-ME IgG (diluted 1:100), affinity-purified according to the method of Plaxton (1989), was used for detection (Maurino et al., 1996, 1997). Bound antibodies were visualized by linking to alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega). The molecular masses of the polypeptides were estimated from a plot of the log of molecular mass of the prestained marker standards versus migration distance (a linear relationship). The markers and the samples were run on the same gel.

For comparison of the relative abundance of different isoforms of NADP-ME among the Flaveria spp., western blots were scanned with a densitometer. The peak area for each form for a given species was determined and expressed as a percentage of the maximum of that isoform among the species examined.

In Situ Immunolocalization

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Samples for microscopy were fixed for 12 to 24 h at 4°C in 2% (v/v) paraformaldehyde and 1.25% (v/v) glutaraldehyde in 50 mm Pipes buffer, pH 7.2. The samples were dehydrated with a graded ethanol series and embedded in London Resin White acrylic resin. Thin sections on uncoated nickel grids were incubated for 1 h in TBST (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 150 mm NaCl, and 0.1% [v/v] Tween 20 [v/v] plus 1% [w/v] BSA) to block nonspecific protein binding on the sections. The sections were then incubated for 16 h with either preimmune serum (without dilution) or affinity purified anti-maize leaf 62-kD NADP-ME IgG (1:10 dilution). After extensive washing with TBST/BSA, the sections were incubated for 1 h with protein A-gold (15 nm) (Amersham) diluted 1:100 with TBST/BSA. The sections were washed with TBST/BSA, TBST, and distilled water prior to poststaining with a 1:4 mixture of 1% (w/v) potassium permanganate and 2% (w/v) aqueous uranyl acetate.

Light Microscopy

Sections (1 μm thick) from the same samples prepared for transmission electron microscopy were dried onto gelatin-coated slides and blocked for 1 h with TBST/BSA. They were then incubated 16 h with the purified antibody or preimmune serum with TBST/BSA. The slides were washed and then treated for 1 h with protein A-gold. The sections were subsequently exposed to a silver enhancement reagent according to the manufacturer's directions (Amersham), stained with 1% (w/v) Safranin O, and photographed using an Aristoplan microscope (Leitz).

Assays of Protein and Chlorophyll

Protein concentration was determined by the method of Sedmak and Grossberg (1977) using BSA as a standard. Chlorophyll was determined after extraction in 96% (v/v) ethanol according to the method of Wintermans and De Mots (1965).

RESULTS

NADP-ME Activity in Leaves of Flaveria spp.

Leaf extracts from Flaveria spp. representing the different photosynthetic types were assayed for NADP-ME activity. There was a progressive increase in activity from C3 to C3-C4, C4-like, and C4 with average values of 131, 188, 870, and 1224 μmol mg−1 chlorophyll h−1, respectively (data for individual species not shown). However, there was a range of activities among the intermediate species from C3-like values to higher values (ranging from 85–359 μmol mg−1 chlorophyll h−1). Among the C3-C4 intermediates having the lowest activity, F. sonorensis did not have a functional C4 cycle, and F. angustifolia and F. linearis had very low C4 cycle activity; the highest NADP-ME activity occurred in F. ramosissima, which had the highest degree of function of a limited C4 cycle in this photosynthetic group (Monson et al., 1986; Moore et al., 1987; Ku et al., 1991). The data, combined with that of Ku et al. (1991), show a clear relationship between the level of NADP-ME activity and other characters that define the degree of C4 photosynthesis in the different Flaveria spp.

Separation of NADP-ME by Suc Density Gradient Centrifugation

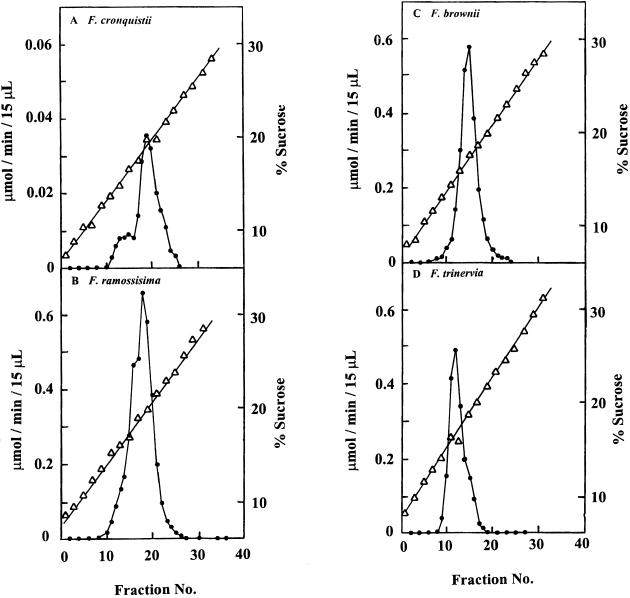

A representative species of each photosynthetic type (C3, F. cronquistii; C3-C4, F. ramosissima; C4-like, F. brownii; and C4, F. trinervia) was used for separation of leaf-soluble protein on Suc density gradients and subsequent fractionation and assay of NADP-ME activity (Fig. 1). After centrifugation, proteins with higher molecular masses resided at higher Suc densities. Although resolution of proteins with small differences in mass were limited by this technique, there was evidence for multiple forms of NADP-ME. In C3 F. cronquistii, two peaks of NADP-ME activity appeared, with the higher mass form (peak fraction 19 at 19.5% Suc) being predominant compared with the lower- mass form (peak fraction 13 at about 16.5% Suc), whereas in C4 F. trinervia there was a major lower-mass form (peak fraction 12 at about 16.5% Suc) and a small shoulder of activity appearing at a higher density. In the C3-C4 F. ramosissima, there was evidence for two dominant forms (around 19.5 and 16.5% Suc), whereas in the C4-like species F. brownii, only one major peak was apparent, with maximum activity occurring in fraction 15 (17.5% Suc). These results suggest that isoforms of NADP-ME with different molecular masses likely exist among the Flaveria spp., and that the relative abundance of the isoforms may vary between the different photosynthetic types.

Figure 1.

Resolution of leaf NADP-ME from representative species of different photosynthetic types of Flaveria spp. by Suc density gradient centrifugation. A, F. cronquistii (C3); B, F. ramosissima (C3-C4); C, F. brownii (C4-like); and D, F. trinervia (C4). The activity of NADP-ME (•) is shown on the left y-axes and the percent Suc in the gradient (Δ) is shown on the right y-axes.

Km for NADP and malate as substrates for NADP-ME were determined on selected gradient fractions for the various species. The most apparent differences were in the Km for NADP. The higher-mass forms of F. cronquistii and F. ramosissima had Km values for NADP (average of two replications) of 150 and 110 μm, respectively (from fractions 18–22), whereas the lower-mass forms had Km values of 11 and 20 μm, respectively (from fractions 12–14). The major lower-mass form in F. trinervia (from fractions 11–13) had a Km value of 35 μm compared with a value of 45 μm for F. brownii (from fractions 14–16). Although detailed analyses of purified isoforms are needed, these results further implicate the existence of different forms of NADP-ME in Flaveria spp., since the peak fractions at different densities exhibit different apparent affinities for NADP and possibly malate.

Immunoblot Analysis of NADP-ME in Different Flaveria spp.

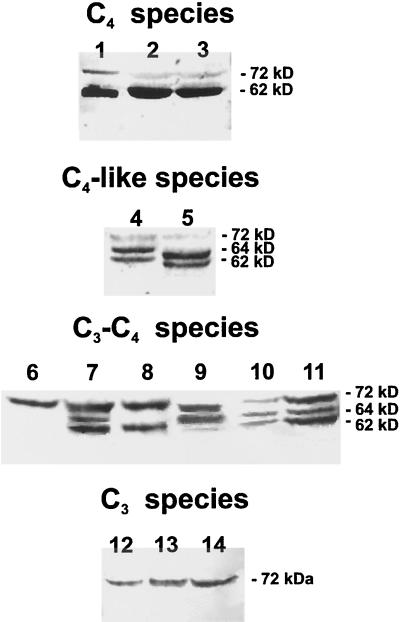

Total proteins from leaves of 13 species of Flaveria were extracted by a phenol procedure in the presence of two proteinase inhibitors and a sulfhydryl reagent to minimize proteolytic cleavage during preparation. These protein extracts were electrophoretically separated in SDS gels, transferred onto nitrocelluose membranes, and probed with affinity-purified antibody prepared against NADP-ME from maize leaves. The maize NADP-ME purified from green leaves is specific for C4 photosynthesis and has a molecular mass of 62 kD (Maurino et al., 1996). This antibody reacts against the photosynthetic isoform of NADP-ME (62-kD monomeric molecular mass) and a nonphotosynthetic isoform (72-kD monomeric molecular mass) present in green and etiolated maize leaves, in maize roots, and in C3 plants such as wheat (Maurino et al., 1996, 1997).

The results with Flaveria spp. show that the antibody reacts with up to three different monomeric molecular forms of NADP-ME in the different species examined (Fig. 2). In the three C3 species, a major reactive band of 72 kD was present (Fig. 2, lanes 12–14). These species have non-Kranz leaf anatomy and are classified as C3 plants based on a number of physiological and biochemical criteria related to photosynthesis (Powell, 1978; Ku et al., 1983; Edwards and Ku, 1987). In the C3-C4 intermediate Flaveria spp., the antibody reacted with one to three different molecular mass monomers of 72, 64, and 62 kD, which was species dependent, with all species having a 72-kD isoform. In the case of F. sonorensis, the only reactive band was at 72 kD (Fig. 2, lane 6). This plant has low apparent photorespiration without C4 photosynthesis, and Rubisco and the C3 pathway are considered to function in mesophyll cells in the same way as in C3 plants, with refixation of photorespired CO2 by Rubisco in bundle-sheath cells (Ku et al., 1991). The other five C3-C4 intermediate plants that exhibit a varying capacity for C4 photosynthesis (Ku et al., 1991) have in addition to the 72-kD form of the enzyme, a 62- and/or a 64-kD reactive form. F. angustifolia (Fig. 2, lane 8) had the 72- and 62-kD forms. All three forms, 72, 64, and 62 kD, are apparent in F. oppositifolia (Fig. 2, lane 7), F. floridana (Fig. 2, lane 10), and F. linearis (Fig. 2, lane 11). F. ramosissima expressed the 72- and the 64-kD forms, with a low level of the 62-kD form (Fig. 2, lane 9).

Figure 2.

Immunoblot analysis of leaf total proteins extracted from different Flaveria spp. Leaf proteins of Flaveria spp. (60 μg) and maize (10 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with purified anti-maize 62-kD NADP-ME IgG. The lines indicate the position of the 72-, 64-, and 62-kD immunoreactive bands. The species used were C4: maize (lane 1); F. trinervia (lane 2); F. bidentis (lane 3). C4-like: F. brownii (lane 4); F. vaginata (lane 5). C3-C4: F. sonorensis (lane 6); F. oppositifolia (lane 7); F. angustifolia (lane 8); F. ramosissima (lane 9); F. floridana (lane 10); F. linearis (lane 11). C3: F. cronquistii (lane 12); F. pringlei (lane 13); F. robusta (lane 14).

The C4-like species F. brownii (Fig. 2, lane 4) strongly expressed the 64- and 62-kD forms and had a faint 72-kD form. F. vaginata (Fig. 2, lane 5) had a faint 72-kD form, and two strongly expressed smaller forms, which have a somewhat lower kD than the 64- and 62-kD forms in F. brownii. Since the 62- and 64-kD forms in F. brownii are similar in size, the major activity of NADP-ME in this species appeared in one peak following Suc density gradient centrifugation (Fig. 1C) at a density intermediate to those of the major peaks for the C3 (Fig. 1A) and C4 Flaverias spp. (Fig. 1D). The 72-kD band was relatively much fainter than that in the C3-C4 intermediates. These C4-like species have high levels of C4 enzymes but lack a strict compartmentalization of Rubisco and PEPCase in bundle-sheath and mesophyll cells as compared with their C4 counterparts (Reed and Chollet, 1985; Moore et al., 1989). In the C4 species F. trinervia (Fig. 2, lane 2) and F. bidentis (Fig. 2, lane 3), the most reactive band was the 62-kD monomer. Nevertheless, a faint 72-kD form was still present and the 64-kD form was expressed at very low levels. The isoform pattern of NADP-ME in C4 Flaveria spp. is similar to that of maize, which has a predominant 62-kD form and little or no 64-kD form.

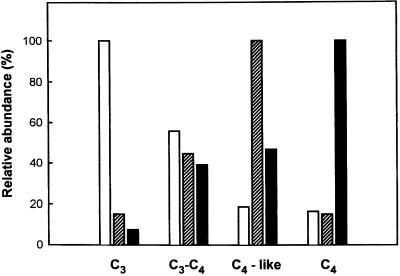

The western blots shown in Figure 2 were scanned and comparisons were made between the different photosynthetic groups for the relative abundance of each isoform (Fig. 3). The same amount of protein was added to the gel, which allowed for an estimate of the relative amount of each form between the photosynthetic types. The results show that from C3 to C3-C4, C4-like, and C4 species there was a progressive decrease in the relative abundance of the 72-kD isoform (100, 56, 19, and 16%, respectively), whereas there was a progressive increase in the relative level of the 62-kD isoform (8 [visible in gel scans but not in Fig. 2], 39, 47, and 100%, respectively). On the other hand, the 64-kD form was most abundant in C4-like and certain C3-C4 species (15 [visible in gel scans but not in Fig. 2], 45, 100, and 15% for the four photosynthetic groups, respectively). Quantitative estimates of the relative amounts of the different forms within a species cannot be made from this analysis since the antibody used may not have the same degree of cross-reactivity with different isoforms (see Maurino et al., 1997). However, the results show a preferential expression of the three isoforms of NADP-ME with different photosynthetic mechanisms in Flaveria spp.

Figure 3.

Relative abundance of the three monomeric isoforms of NADP-ME in the different photosynthetic types of Flaveria spp.. The western blots from the results in Figure 2 were scanned, the areas of the peaks corresponding to the monomeric forms were determined, the average of each form within each photosynthetic type was calculated, and the relative abundance was determined. Immunoblots were repeated three times with the same phenol extract for all species; duplicate extracts from separate leaves with a species representing each photosynthetic type gave similar results. The results are presented for each form as a percentage of the maximum, with the photosynthetic group having the maximum amount of that form taken as 100%. Very low levels of the 62-kD (black columns) and 64-kD (striped columns) forms were detected in scans of the C3 species, although they are not apparent in the immunoblots in Figure 2 (lanes 12–14). The white columns represent 72-kD forms.

When the total protein extracts from different tissues of F. pringlei (C3), F. floridana (C3-C4), and F. trinervia (C4) (leaf, stem, and root) were tested with the maize NADP-ME antibody, only the 72-kD form was found in stems and roots (data not shown). On the other hand, the 62-kD form was found in large amounts in the leaves of F. trinervia and both the 62- and 64-kD forms in leaves of F. floridana (C3-C4) versus trace amounts in leaves of F. pringlei (C3) (data not shown; see Fig. 2). Again, these results indicate that there are three major isoforms of NADP-ME in Flaveria spp. when examined at the monomeric level and they are expressed in tissue-specific and photosynthetic- mechanism-specific manners.

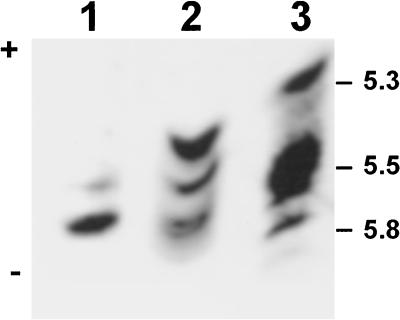

Isoform Pattern of NADP-ME as Resolved by IEF

Since three monomeric forms of NADP-ME were observed in various Flaveria spp. on western blots, the isoform pattern of NADP-ME in leaf extracts of C3 F. pringlei, C3-C4 F. floridana, and C4 F. trinervia was determined by nondenaturing IEF. The results show that based on pI and activity data, there were three native NADP-ME isoforms of roughly similar activity in F. floridana (Fig. 4, lane 2), which corresponds to the amounts of the three monomeric forms as revealed by western analysis (Figs. 2 and 3). By comparison, the C4 species F. trinervia, which has a dominant 62-kD monomeric form and low levels of the 72- and 64-kD forms (Figs. 2 and 3), had major activity on native IEF gels at a pI of 5.5, along with two relatively minor bands (Fig. 4, lane 3). On the other hand, the C3 species F. pringlei, which has a predominant 72-kD monomeric form, had a major band of activity that corresponds to the minor, more alkaline band in the C4 and C3-C4 extracts on native IEF gels (Fig. 4, lane 1). The pI of these forms were between 5.3 and 5.8. Taken together, these results suggest that three active isoforms of NADP-ME with different monomeric sizes and pI are expressed in Flaveria spp. at different levels. In addition, comparisons of the three isoforms on native IEF gels (Fig. 4) with those on SDS gels (Fig. 2) for the three species suggest that the most alkaline form on the native IEF gel is the 72-kD form (constitutively expressed in all species), with the middle band being the 62-kD form (highly expressed only in C4 species), and the most acidic form being the 64-kD form (highly expressed in some C3-C4 and C4-like species).

Figure 4.

Activity staining of leaf NADP-ME from F. pringlei (C3), F. floridana (C3-C4 intermediate), and F. trinervia (C4) on native IEF gels. The pH gradient used for IEF was from 5.0 to 7.0. The calculated native pI of the reactive bands are between 5.3 and 5.8. Leaf protein extracts were made from F. pringlei (lane 1), F. floridana (lane 2), and F. trinervia (lane 3). The amount of protein loaded was equivalent to 1 milliunit of NADP-ME activity.

Immunolocalization Studies

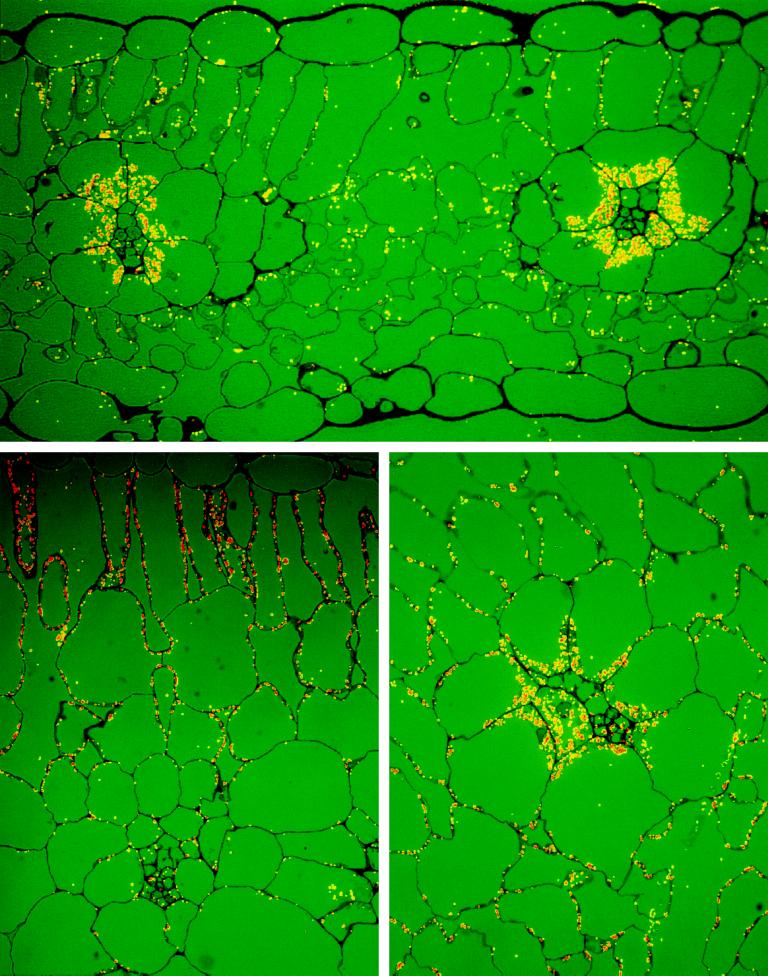

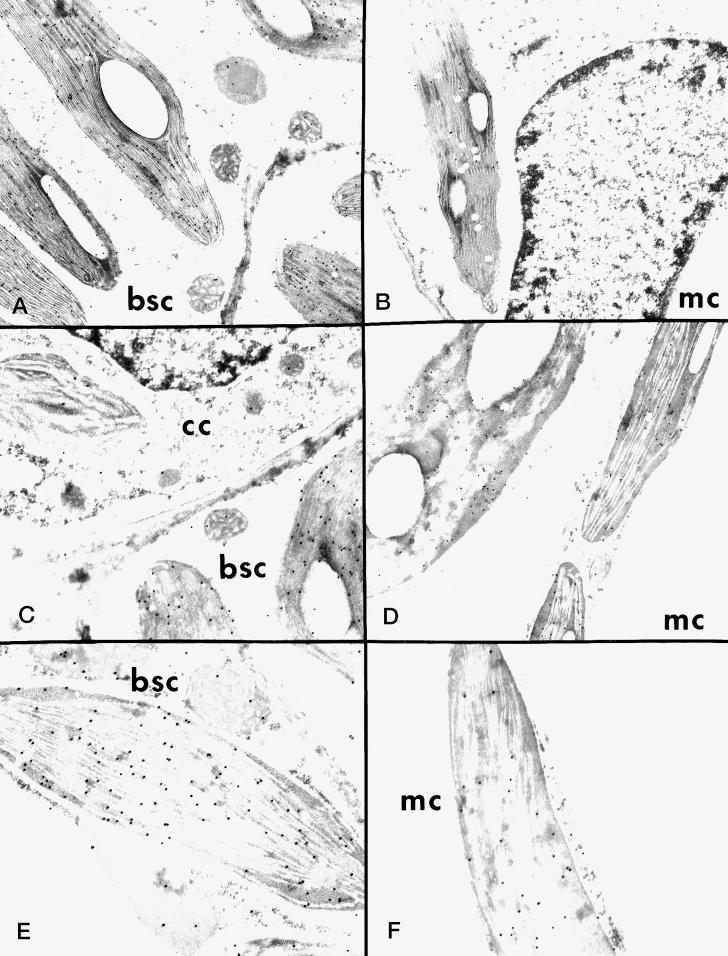

Immunolocalization with the antibody against the 62-kD NADP-ME from maize leaves was studied by light (Fig. 5) and electron microscopy (Fig. 6) to analyze the distribution of NADP-ME among leaf cell types in different Flaveria spp. The background labeling with preimmune serum was very low in all cases (data not shown). In F. bidentis (C4), where the majority of the enzyme was the 62-kD monomeric form (Fig. 2, lane 3), immunolocalization at the light microscope level showed that there was very strong labeling in the bundle-sheath cells and little labeling in the mesophyll cells (Fig. 5). Electron microscopy shows that the gold particles were largely localized in bundle-sheath chloroplasts (Fig. 6, A and C). Whereas the bundle-sheath plastid is heavily labeled, the plastid in the companion cell had little labeling (Fig. 6C). In the mesophyll cell of F. trinervia (C4) there was little labeling in the chloroplasts, whereas no labeling was observed in the nucleus or the cytosol (Fig. 6B).

Figure 5.

Light microscopy of in situ immunolocalization of NADP-ME in leaves of F. bidentis (C4, upper panel), F. robusta (C3, lower left panel), and F. ramosissima (C3-C4, lower right panel).

Figure 6.

Electron microscopy of in situ immunolocalization of NADP-ME in leaves of Flaveria spp. A to C, F. bidentis (C4); D, F. robusta (C3); E and F, F. ramosissima (C3-C4). bsc, Bundle-sheath cell; mc, mesophyll cell; cc, companion cell.

In F. robusta (C3), where the 72-kD monomer was the main immunoreactive form (Fig. 2, lane 14), the heaviest labeling appeared in the upper layer of palisade mesophyll cells (Fig. 5). High-resolution immunolocalization by electron microscopy shows that labeling occurred in the plastids of the mesophyll cells (Fig. 6D). In the case of F. ramosissima (C3-C4 intermediate), which expresses the 72- and 64-kD forms of NADP-ME, with a very faint band of 62 kD (Fig. 2, lane 9), labeling occurred in both mesophyll and bundle-sheath cells, with strong labeling in the latter (Fig. 5). Moreover, the majority of the label in both bundle-sheath (Fig. 6E) and mesophyll cells (Fig. 6F) was associated with plastids, although some label occurred outside the chloroplast. These in situ results (Fig. 6) indicate that the three isoforms of NADP-ME in Flaveria spp. are all located largely, if not exclusively, in chloroplasts.

DISCUSSION

Isoforms of NADP-ME in Flaveria spp.

C4 and C3 Species

The C3 species of Flaveria have low activities of NADP-ME, which are largely attributed to a higher-molecular- mass native form of the enzyme on Suc density gradients, with a minor peak of activity for a lower-molecular-mass form (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, the C4 Flaveria spp. have very high activities of NADP-ME in leaves, which appears as a major, lower-mass native form (Fig. 1D). This difference between C3 and C4 species in molecular mass of NADP-ME within the genus Flaveria is analogous to intergenus differences that we observed earlier: the native form of NADP-ME in wheat, a C3 species, has a higher mass/lower activity than the native form in green maize leaves, which is utilized in C4 photosynthesis (Casati et al., 1997; Maurino et al., 1997). Maize leaves also have a native form of higher mass that is constitutively expressed in roots, etiolated leaves, and at low levels in green leaves, and this form corresponds to the higher-mass form in wheat (Maurino et al., 1997). The higher-mass form of the enzyme in C3 species of Flaveria appears to have a higher Km value for NADP than the lower-mass form in C4 species of Flaveria, which is consistent with reports that the enzyme from leaves of C3 and C4 species has different kinetic properties (see Edwards and Andreo, 1992).

Immunoblots of denatured C3 Flaveria leaf protein, probed with antibody to the maize 62-kD C4 form of the enzyme, show that the only immunoreactive band is a 72-kD monomer (Fig. 2). Only very low levels of the smaller-molecular-mass forms (62 and 64 kD) were detected in scans of the western blots (Fig. 3). This result is consistent with the observation that the major leaf NADP-ME in F. cronquistii has a higher density on a Suc gradient and thus a higher mass (Fig. 1A). This high-molecular-mass (72-kD) monomer in C3 species of Flaveria corresponds in size to the 72-kD monomer of NADP-ME in the C3 species wheat (Maurino et al., 1997) and to the larger molecular mass, constitutive 72-kD monomer of the enzyme that occurs in maize roots, etiolated leaves, and at low levels in green leaves (Maurino et al., 1997). Previously, Cameron et al. (1989) reported no immunoreactivity of NADP-ME in leaf extracts of C3 F. pringlei in western blots using antibodies against the maize enzyme, which may be due to differences in the epitopes that the antibodies prepared with the maize 62-kD protein can recognize (also see Maurino et al., 1997).

On the other hand, the C4 Flaveria spp. show a very reactive 62-kD band of NADP-ME and minor bands at 64 and 72 kD (Fig. 3). Again, this is consistent with the notion that the major NADP-ME in leaves of C4 F. trinervia resides at a lower density on Suc gradients and thus has a lower mass (Fig. 1D). This 62-kD form also corresponds in size and abundance to the major form of the enzyme in maize leaves, which is involved in C4 photosynthesis. The 72-kD monomer is constitutively expressed in leaves, stems, and roots of C3 and C4 species of Flaveria, whereas the 62-kD monomer and a minor 64-kD monomer occur only in green leaves of the C4 species. As in maize, these data suggest that the 72-kD NADP-ME isoform is not involved in photosynthetic carbon metabolism, whereas the 62-kD form participates in carbon fixation via the C4 pathway. Two forms of NADP-ME with different molecular masses were previously observed in leaves of C4 species of F. trinervia in western blots with maize NADP-ME antibody, including a predominant, low-mass form (Cameron and Basset, 1988). The sizes of the monomeric forms were not determined in this latter study. Previous studies showed that the native, active form of plant NADP-ME is a homotetramer (Edwards and Andreo, 1992; Maurino et al., 1997). Thus, in leaves, stems, and roots of C3 species of Flaveria and in stems and roots of C4 Flaveria spp., the apparent predominant form of the enzyme may consist of a homotetramer of 72-kD subunits, whereas in leaves of C4 Flaveria spp. the apparent predominant form of the enzyme may be a homotetramer of 62-kD polypeptides. These results are consistent with the native form of the enzyme existing as one dominant band of activity in nondenaturing IEF gels in C3 and C4 species of Flaveria, but with different pI (Fig. 4). So far in Flaveria spp., NADP-ME genes have been cloned from the C3 F. pringlei (Lipka et al., 1994) and the C4 F. trinervia (Borsch and Westhoff, 1990), and both encode a subunit with deduced molecular mass of 62 kD. The genomic clones of NADP-ME isolated from another C4 species, F. bidentis, remain to be characterized in terms of the sizes of their protein products (Marshall et al., 1996).

C3-C4 Species

There appeared to be at least two forms of native NADP-ME in leaves of the C3-C4 intermediate species F. ramosissima when examined on Suc density gradients (Fig. 1B). Western-blot analysis indicated that depending upon the species, there are up to three monomeric forms of the enzyme, 62, 64, and 72 kD, occurring among the intermediates (Figs. 2 and 3). For example, F. floridana showed three isoforms on a western blot of denatured protein (Fig. 2) and on a native IEF gel with activity staining (Fig. 4). This indicates that as many as three NADP-ME isoforms occur among intermediate species. It is apparent that the relative quantity of these products varies among the intermediates (Fig. 2). In leaves of the C3-C4 intermediate F. sonorensis, which does not have a functional C4 cycle (Ku et al., 1991), the 72-kD form is predominant, which is similar to the situation in C3 species. In other intermediates, where there is evidence for a limited degree of functioning of C4 photosynthesis, such as F. ramosissima, F. linearis, and F. floridana (Monson et al., 1986; Moore et al., 1987; Ku et al., 1991), multiple forms of NADP-ME are present. Previously, Cameron and Basset (1988) suggested from western analysis that there is only one form of NADP-ME in leaves of intermediates (F. floridana, F. oppositifolia, and F. linearis), but these results were inconclusive due to the poor reactivity of their antibody.

C4-Like Species

In leaves of the C4-like species F. brownii, there was one major band of NADP-ME activity on a Suc density gradient (Fig. 1C); however, two major bands of 62 and 64 kD were revealed on western blots of SDS gels (Fig. 2, lane 4). Thus, this C4-like species has a significant amount of the 64-kD form, which occurs to a lesser extent in intermediates (Fig. 3), and a 62-kD form, which is the major form in C4 species. The C4-like species F. vaginata also has two major forms on SDS gels; however, these are slightly smaller than the 64- and 62-kD forms in F. brownii.

Collectively, these data demonstrate the presence of three NADP-ME isoforms of different molecular masses and pI in Flaveria spp., with a progressive increase in expression of the 64-kD form from C3 to intermediate to C4-like, and an increase in expression of the 62-kD form and a decrease in expression of the 72-kD form from C3 to C3-C4, C4-like and C4 species of Flaveria.

Localization of NADP-ME in Flaveria spp. Leaves

C4 and C3 Species

Immunolocalization studies of leaves of C4 species of Flaveria show that the major labeling occurs in bundle-sheath chloroplasts, with minor labeling in mesophyll chloroplasts (Figs. 5 and 6). This is consistent with the C4 form of the enzyme having an essential function in the bundle-sheath cells of certain C4 plants in donating CO2 to RuBP carboxylase. In studies with isolated mesophyll and bundle-sheath protoplasts of C4 F. trinervia, it was shown that high NADP-ME activity occurs in bundle-sheath protoplasts (40-fold higher activity than in mesophyll protoplasts), with compartmentation of the enzyme in the chloroplast (Moore et al., 1984); recently it was shown that isolated bundle-sheath chloroplasts of F. bidentis have high activity of NADP-ME (Meister et al., 1996). In maize, bundle-sheath chloroplasts have high levels of the 62-kD form, which provides direct evidence for its role in C4 photosynthesis, whereas the mesophyll chloroplasts have only low levels of the constitutive 72-kD form (Maurino et al., 1997). Thus, by analogy, the low level of labeling in the mesophyll chloroplasts of F. trinervia may be attributed to the constitutive 72-kD form.

In the C3 species of Flaveria, which have the 72-kD NADP-ME form, labeling occurs predominantly in the chloroplasts of the upper palisade cells (Figs. 5 and 6). This is consistent with results with wheat in which labeling occurred mainly in mesophyll chloroplasts. The constitutive form may be involved in providing NADPH for synthesis of lipids or isoprenoids in plastids (see Maurino et al., 1997).

C3-C4 Intermediate Species

Evidence that intermediates have incomplete development of C4 photosynthesis at the biochemical level was previously shown by immunocytochemical studies with several C3-C4 Flaveria spp. (F. linearis, F. floridana, and F. chloraefolia). Neither Rubisco nor PEPCase was specifically located in one cell type, as is the case in C4 species, but rather they each occurred in both mesophyll and bundle-sheath cells (Reed and Chollet, 1985). In the present study, major immunolabeling of NADP-ME was found in bundle-sheath chloroplasts, whereas significant labeling also occurred in mesophyll chloroplasts of the C3-C4 intermediate F. ramosissima (Figs. 5 and 6), a species that has substantial C4 cycle function (see Ku et al., 1991). The distribution of the three forms identified on western blots between the two cell chloroplast types is not known. It was previously reported (Moore et al., 1988) that within the leaf of this C3-C4 plant there is a gradation of decreasing PEPCase activity along with increasing NADP-ME and Gly decarboxylase activities from the peripheral mesophyll cells to the bundle-sheath cells. In this way, apparent photorespiration may be reduced by two mechanisms in this species, one through concentrating CO2 by C4 acid decarboxylation in the bundle-sheath and the other through refixation of the photorespired CO2 in the bundle-sheath cells. Although the compartmentation of the different forms of NADP-ME in the leaves of C3-C4 intermediate and C4-like Flaveria spp. is uncertain, if the 62- and 64-kD forms are associated with the C4 cycle they may be enriched in the bundle-sheath chloroplasts.

Finally, since immunolocalization studies were performed with antibody raised against a chloroplast-specific isoform of NADP-ME from maize, it is possible that nonchloroplastic forms exist in Flaveria spp. that have low homology to the chloroplast forms and thus were not detected by the antibody. If so, these are likely low-abundance, low-activity forms, since cellular fractionation studies show that association of NADP-ME activity with chloroplasts is correlated with immunolocalization analysis (analysis of compartmentation of enzyme activity in C4 species of Flaveria by Moore et al. [1984] and Meister et al. [1996], versus the immunological results of the present study, and analysis of activity versus immunoblot reactivity of fractionated mesophyll protoplasts of wheat by Maurino et al. [1997]).

Isoforms and Gene Family of NADP-ME in Flaveria spp.

Marshall et al. (1996) showed that the C3 F. pringlei and the C4 F. bidentis and F. trinervia have at least three and perhaps four NADP-ME genes. In examining two of these genes from F. bidentis, Me1 and Me2, in detail, they concluded that these genes are very similar in sequence, that both are present in C3 and C4 species of Flaveria, and that they both encode putative transit peptide sequences for targeting their preproteins into chloroplasts. They suggested that these are paralogous genes arising by gene duplication from a common ancestral species. Also, from examination of Me1 and Me2 mRNA levels there was evidence that Me1 encodes the C4 form of the enzyme in leaves (leaf-specific, light-dependent expression in C4 plants only) and that Me2 is constitutively expressed (lack of organ specificity in expression, low level of expression). The 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of the Me1 gene are important for bundle-sheath specificity and high-level expression in leaves, respectively (Marshall et al., 1997). Thus, at least two chloroplastic forms of NADP-ME might be expected to occur in Flaveria spp. It is reasonable to suggest from the results of the present study that Me1 encodes the 62-kD form that is targeted to bundle-sheath chloroplasts in C4 species and that Me2 encodes the constitutive 72-kD form that is targeted to leaf plastids and stem and root tissues of both C3 and C4 species. In addition, the present study identified a third form of the enzyme in Flaveria spp., a 64-kD form that is most abundant in C4-like and certain C3-C4 intermediate species and occurs in green leaf tissue but not in roots and stems of the intermediate species examined. Thus, this may be the product of a third NADP-ME gene, which is more actively expressed during evolutionary transition from C3 to C4 photosynthesis. Sequencing of these three different monomeric forms will be required to match proteins to the NADP-ME genes and cDNAs that have been isolated.

The preferential expression of the 64-kD NADP-ME isoform in C4-like and certain C3-C4 intermediate Flaveria spp. and the 62-kD form in C4 Flaveria spp. is noteworthy. Perhaps these isoforms have different kinetic properties with respect to substrates or cofactors that may reflect metabolic adaptations to differences in C4 capacity in the different photosynthetic types. An examination of the strategies employed by C4 plants to acquire the various components of C4 photosynthesis during their evolution from C3 plants show that different mechanisms were utilized (Ku et al., 1996). These include changes in cell-specific expression (e.g. carbonic anhydrase), gene duplication coupled with acquisition of strong promoters for high-level expression (e.g. PEPCase), and acquisition of strong promoters for high-level expression of chloroplast-specific isoforms in a cell-specific manner (e.g. pyruvate, Pi dikinase). In this study we have demonstrated the presence of three chloroplastic NADP-ME isoforms, presumably encoded by three different isogenes, in leaves of all types of photosynthetic Flaveria spp. (C3, C3-C4, C4-like, and C4), but differing in relative abundance (Figs. 3, 5, and 6). These results suggest that a differential expression of the existing NADP-ME genes encoding the chloroplastic forms in a tissue- and cell-specific manner was involved in the evolution of C4 photosynthesis in the genus Flaveria. The genes encoding the 62- and 64-kD forms must have been altered for increased expression during the evolution of C4 photosynthesis, and in the case of the 62-kD form, it is also clear that these alterations must have also included an element for bundle-sheath-specific expression.

Abbreviations:

- NADP-ME

NADP-malic enzyme

- PEPCase

PEP carboxylase

- RuBP

ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate

Footnotes

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant no. IBN 93-17756 to G.E.E.) and by grants from the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas and Fundación Antorchas (to C.S.A.).

LITERATURE CITED

- Borsch D, Westhoff P. Primary structure of NADP-dependent malic enzyme in the dicotyledonous Flaveria trinervia. FEBS Lett. 1990;273:111–115. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81063-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette WN. “Western blotting”: electrophoretic transfer of proteins from sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels to unmodified nitrocellulose and radiographic detection with antibody and radioiodinated protein A. Anal Biochem. 1981;112:195–203. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron RG, Bassett CL. Inheritance of C4 enzymes associated with carbon fixation in Flaveria species. Plant Physiol. 1988;88:532–536. doi: 10.1104/pp.88.3.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron RG, Bassett CL, Bouton JH, Brown RH. Transfer of C4 photosynthetic characters through hybridization of Flaveria species. Plant Physiol. 1989;90:1538–1545. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.4.1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casati P, Spampinato CP, Andreo CS. Characteristics and physiological function of NADP-malic enzyme from wheat. Plant Cell Physiol. 1997;38:928–934. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards GE, Andreo CS. NADP-malic enzyme from plants. Phytochemistry. 1992;31:1845–1857. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(92)80322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards GE, Ku MSB (1987) The biochemistry of C3-C4 intermediates. In MD Hatch, K Boardman, eds, The Biochemistry of Plants, Vol 14. Academic Press, New York, pp 275–325

- Edwards GE, Walker DA (1983) C3, C4: Mechanisms, and Cellular and Environmental Regulation of Photosynthesis. Blackwell Scientific Publishers, Oxford, UK

- Hatch MD. C4 photosynthesis: a unique blend of modified biochemistry, anatomy and ultrastructure. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;895:81–106. [Google Scholar]

- Ku MSB, Kano-Murakami Y, Matsuoka M. Evolution and expression of C4 photosynthesis genes. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:949–957. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.4.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku MSB, Monson RK, Littlejohn RO, Nakamoto H, Fisher DB, Edwards GE. Photosynthetic characteristics of C3-C4 intermediate Flaveria species. I. Leaf anatomy, photosynthetic responses to O2 and CO2, and activities of key enzymes in the C3 and C4 pathways. Plant Physiol. 1983;71:944–948. doi: 10.1104/pp.71.4.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku MSB, Wu J, Dai Z, Scott RA, Chu C, Edwards GE. Photosynthetic and photorespiratory characteristics of Flaveria species. Plant Physiol. 1991;96:518–528. doi: 10.1104/pp.96.2.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipka B, Steinmuller K, Rosche E, Borsch D, Westhoff P. The C3 plant Flaveria pringlei contains a plastidic NADP-malic enzyme which is orthologous to the C4 isoform of the C4 plant F. trinervia. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;26:1775–1783. doi: 10.1007/BF00019491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JS, Stubbs JD, Chitty JA, Surin B, Taylor WC. Expression of the C4 Me1 gene from Flaveria bidentis requires an interaction between 5′ and 3′ sequences. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1515–1525. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.9.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JS, Stubbs JD, Taylor WC. Two genes encode highly similar chloroplastic NADP-malic enzymes in Flaveria. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:1251–1261. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.4.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurino VG, Drincovich MF, Andreo CS. NADP-malic enzyme isoforms in maize leaves. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1996;38:239–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurino VG, Drincovich MF, Casati P, Andreo CS, Edwards GE, Ku MSB, Gupta SK, Franceschi VR. NADP-malic enzyme: immunolocalization in different tissues of the C4 plant maize and the C3 plant wheat. J Exp Bot. 1997;48:799–811. [Google Scholar]

- Meister M, Agostino A, Hatch MD. The roles of malate and aspartate in C4 photosynthetic metabolism of Flaveria bidentis (L.) Planta. 1996;199:262–269. [Google Scholar]

- Monson RK, Edwards GE, Ku MSB. C3-C4 intermediate photosynthesis in plants. BioSci. 1984;34:563–574. [Google Scholar]

- Monson RK, Moore Bd, Ku MSB, Edwards GE. Co-function of C3 and C4-photosynthetic pathways in C3, C4 and C3-C4 Flaveria species. Planta. 1986;168:493–502. doi: 10.1007/BF00392268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore Bd, Ku MSB, Edwards GE. Isolation of leaf bundle-sheath protoplasts from C4 dicot species and intracellular location of selected enzymes. Plant Sci Lett. 1984;35:127–138. [Google Scholar]

- Moore Bd, Ku MSB, Edwards GE. C4 photosynthesis and light dependent accumulation of inorganic carbon in leaves of C3-C4 and C4 Flaveria species. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1987;14:657–668. [Google Scholar]

- Moore Bd, Ku MSB, Edwards GE. Expression of C4-like photosynthesis in several species of Flaveria. Plant Cell Environ. 1989;12:541–549. [Google Scholar]

- Moore Bd, Monson RK, Ku MSB, Edwards GE. Plant Cell Physiol. 1988;29:999–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Plaxton WC. Molecular and immunological characterization of plastid and cytosolic pyruvate kinase isozymes from castor-oil plant endosperm and leaf. Eur J Biochem. 1989;181:443–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb14745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell AM. Systematics of Flaveria (Flaveriinae-Asteraceae) Ann Missouri Bot Garden. 1978;65:591–636. [Google Scholar]

- Rajeevan MS, Basset CL, Hughes DW. Isolation and characterization of cDNA clones for NADP-malic enzyme from leaves of Flaveria: transcript abundance distinguishes C3, C3-C4 and C4 photosynthetic types. Plant Mol Biol. 1991;17:371–383. doi: 10.1007/BF00040632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawsthorne S. C3-C4 intermediate photosynthesis: linking physiology to gene expression. Plant J. 1992;2:267–274. [Google Scholar]

- Reed JE, Chollet R. Immunofluorescent localization of phophoenolpyruvate carboxylase and ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase proteins in leaves of C3, C4 and C3-C4 intermediate Flaveria species. Planta. 1985;165:439–445. doi: 10.1007/BF00398088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedmak JJ, Grossberg SE. A rapid, sensitive, and versatile assay for protein using Coomassie brillant blue G250. Anal Biochem. 1977;79:544–552. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(77)90428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Etten JL, Freer SN, McCune BK. J Bacteriol. 1979;138:650–652. doi: 10.1128/jb.138.2.650-652.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintermans JFGM, De Mots A. Spectrophotometric characteristics of chlorophylls and their pheophytins in ethanol. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1965;109:448–453. doi: 10.1016/0926-6585(65)90170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]