Abstract

H2S generated by the enzyme cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE) has been implicated in O2 sensing by the carotid body. The objectives of the present study were to determine whether glomus cells, the primary site of hypoxic sensing in the carotid body, generate H2S in an O2-sensitive manner and whether endogenous H2S is required for O2 sensing by glomus cells. Experiments were performed on glomus cells harvested from anesthetized adult rats as well as age and sex-matched CSE+/+ and CSE−/− mice. Physiological levels of hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg) increased H2S levels in glomus cells, and dl-propargylglycine (PAG), a CSE inhibitor, prevented this response in a dose-dependent manner. Catecholamine (CA) secretion from glomus cells was monitored by carbon-fiber amperometry. Hypoxia increased CA secretion from rat and mouse glomus cells, and this response was markedly attenuated by PAG and in cells from CSE−/− mice. CA secretion evoked by 40 mM KCl, however, was unaffected by PAG or CSE deletion. Exogenous application of a H2S donor (50 μM NaHS) increased cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) in glomus cells, with a time course and magnitude that are similar to that produced by hypoxia. [Ca2+]i responses to NaHS and hypoxia were markedly attenuated in the presence of Ca2+-free medium or cadmium chloride, a pan voltage-gated Ca2+ channel blocker, or nifedipine, an L-type Ca2+ channel inhibitor, suggesting that both hypoxia and H2S share common Ca2+-activating mechanisms. These results demonstrate that H2S generated by CSE is a physiologic mediator of the glomus cell's response to hypoxia.

Keywords: O2 sensing, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, gasotransmitters, arterial chemoreceptors, breathing

an adequate supply of O2 is essential for survival of mammalian cells, and hypoxia (i.e., decreased O2 availability) profoundly impacts physiological systems. Recent studies have shown that endogenously generated hydrogen sulfide (H2S), a gaseous messenger, plays an important role in mediating physiological responses to hypoxia. For instance, H2S generated by cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS) has been implicated in O2 sensing by fish gill chemoreceptors (21) and in mediating blood vessel relaxation by hypoxia in mouse brain (17). In mammals, carotid bodies are the primary sensory organs for detecting changes in arterial blood O2 (13). Hypoxia increases the sensory nerve activity of the carotid body, which is transmitted to brainstem neurons, leading to reflex stimulation of breathing and elevation of blood pressure. Recent studies establish that 1) CBS and cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE), the enzymes that catalyze H2S generation, are expressed in carotid bodies (15, 22); 2) hypoxia increases H2S generation (22); 3) exogenous application of an H2S donor stimulates carotid body activity (15, 22); and 4) blockade of endogenous H2S generation impairs carotid body response to hypoxia as well as stimulation of breathing by low O2 (15, 22). While these studies demonstrate that endogenous H2S is a physiologic mediator of sensory response to hypoxia, the site of its action in the carotid body has not been established.

The carotid body is primarily composed of two cell types: 1) glomus cells or type I cells, which are of a neuronal phenotype; and 2) sustentacular or type II cells, which resemble glial cells of the nervous system (9, 10, 12, 19). Type I cells express a variety of neurotransmitters and are in synaptic contact with the afferent nerve endings of the sinus nerve (6, 14, 16, 18). Considerable evidence suggests that type I cells are the primary site of O2 sensing in the carotid body (13). Exogenous application of H2S donors mimics several effects of hypoxia on glomus cells including inhibition of Ca2+-activated K+ channels (26) and background (TASK) K+ channels (3). Whether endogenous H2S contributes to the glomus cell's response to hypoxia, however, has not been examined. Although the carotid body expresses both CBS and CSE, our previous study showed that genetic deletion of CSE alone is sufficient to disrupt the carotid body sensory response to hypoxia in mice (22). Consequently, in the present study, we assessed the role of the CSE-H2S system on glomus cell responses to hypoxia. Glomus cell response to hypoxia was determined by monitoring catecholamine (CA)secretion in response to low O2. Our results demonstrate that pharmacological as well as genetic disruption of the CSE-H2S system disrupts Ca2+ signaling in glomus cells, thereby impairing hypoxia-evoked exocytosis.1

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Chicago. All experiments were performed on adult male Sprague-Dawley rats as well as age and sex-matched CSE+/+ and CSE−/− mice.

Primary cultures of glomus cells.

Carotid artery bifurcations were dissected from anesthetized (urethane; 1.2 g/kg, ip) rats and mice. Carotid bodies were removed and cleaned from surrounding tissues, and glomus cells were dissociated using a mixture of collagenase P (2 mg/ml; Roche), DNase (15 μg/ml; Sigma), and bovine serum albumin (BSA; 3 mg/ml; Sigma) at 37°C for 20 min, followed by a 15-min incubation in medium containing DNAse (30 μg/ml). Cells were plated on collagen (type VII; Sigma)-coated coverslips and maintained at 37°C in a 7% CO2 + 20% O2 incubator for 24 h. The growth medium consisted of F-12K medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum, insulin-transferrin-selenium (ITS-X; Invitrogen), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine mixture (Invitrogen).

Immunocytochemistry.

Glomus cells grown on collagen-coated coverslips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. Permeabilized cells were incubated with polyclonal rabbit anti-CSE antibody raised using bacterially purified full-length His-tagged CSE as antigen (1:400), and monoclonal mouse anti-tyrosine hydroxylase antibody (1:2,000; Sigma), an established marker of glomus cells (10, 19), followed by Texas red-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:250; Molecular Probes) in phosphate-buffered solution (PBS) containing 1% normal goat serum and 0.2% Triton X-100. Cells mounted in Vectashield containing DAPI (Vector Labs) were analyzed using a fluorescent microscope (Eclipse E600; Nikon).

Measurements of H2S.

H2S levels in the glomus cells were assayed as described previously (22). Briefly, glomus cell homogenates were prepared in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The enzyme reaction was carried out in sealed tubes flushed with either O2 or 1% O2-99% N2 gas mixture. The Po2 of the reaction medium was determined by blood gas analyzer (ABL5). The assay mixture in a total volume of 500 μl contained (in final concentration) 800 μM l-cysteine, 80 μM pyridoxal 5′-phosphate, 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and cell homogenate (2 μg of protein). The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h and at the end of the reaction, alkaline zinc acetate (1% wt/vol; 250 μl) and trichloroacetic acid (10% vol/vol) were added sequentially to trap H2S generated and to stop the reaction, respectively. The zinc sulfide formed was reacted sequentially with acidic N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine sulfate (20 μM) and ferric chloride (30 μM), and the absorbance was measured at 670 nm using a microplate reader. A standard curve relating the concentration of Na2S and absorbance was used to calculate H2S concentration and values are expressed as nanomoles of H2S formed per hour per milligram protein.

Measurements of catecholamine secretion by amperometry.

Catecholamine secretion from glomus cells was monitored by amperometry using carbon-fiber electrode. The electrode was held at +700 mV versus a ground electrode using an NPI VA-10 amplifier to oxidize catecholamines. The amperometric signal was low-pass filtered at 2 kHz (eight-pole Bessel; Warner Instruments) and sampled into a computer at 10 kHz using a 16-bit analog-to-digital converter (National Instruments). Records with root-mean-square noise >1.0 pA were not analyzed. Amperometric spike features, quantal size, and kinetic parameters were analyzed using a series of macros written in Igor Pro (WaveMetrics). The detection threshold for an event was set at four to five times the root-mean-square noise. The area under individual amperometric spikes is equal to the charge (picocoulombs) per event, referred to as Q. The number of oxidized neurotransmitter molecules (N) was calculated using the Faraday equation, N = Q/ne, with n = 2 electrons per oxidized molecule of transmitter, and where e is the elemental charge (1.603 × 10−19 C). Because the number of events varied considerably from cell to cell, the data from each cell were averaged to provide a single number for the overall statistic. The number of secretory events and the amount of catecholamine secreted per event were analyzed in each experiment, and the data are expressed as total catecholamines secreted.

Amperometric recording solutions and stimulation protocols.

Amperometric recordings were made from adherent cells that were under constant perfusion (flow rate of ∼1.0 ml/min; chamber volume, ∼80 μl). All experiments were performed at ambient temperature (23 ± 2°C), and the solutions had the following composition (in mM): 138 NaCl, 1.3 CaCl2, 0.4 MgCl2-6 H2O, 0.5 MgSO4-7H2O, 5.3 KCl, 0.4 KH2PO4, 0.3 Na2HPO4-7H2O, 5.6 dextrose, and 20 HEPES at pH 7.35 and osmolarity (300 mosM). Control normoxic solutions were equilibrated with room air (Po2 ∼146 mmHg). For challenging with hypoxia, solutions were degassed and equilibrated with hypoxic gas mixture that resulted in a final medium Po2 ∼30 mmHg as measured by blood gas analyzer. In experiments testing the effects of Ca2+-free medium, Ca2+ was omitted in the medium and EGTA (0.5 mM), a Ca2+ chelating agent, was added to the medium.

Measurements of [Ca2+]i.

Cells were incubated in Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) with 2 μM Fura-2-AM and 1 mg/ml albumin for 30 min and then washed in a Fura-2-free solution for 30 min at 37°C. The coverslip was transferred to an experimental chamber for determining the changes in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i). Background fluorescence at 340 and 380 nm wavelengths was obtained from an area of the coverslip that was devoid of cells. On each coverslip, five to twelve glomus cells were selected (identified by their characteristic clustering) and individual cells were imaged. Image pairs (one at 340 and the other at 380 nm) were obtained every 2 s by averaging 16 frames at each wavelength. Data were continuously collected throughout the experiment. Background fluorescence was subtracted from the individual wavelengths. The image obtained at 340 nm was divided by the 380 nm image to obtain ratiometric image. Ratios were converted to free [Ca2+]i using calibration curves constructed in vitro by adding Fura-2 (50 μM free acid) to solutions containing known concentrations of Ca2+ (0–2,000 nM). The recording chamber was continually superfused with solution from gravity-fed reservoirs.

Drugs and chemicals.

dl-propargylglycine (PAG; Sigma-Aldrich), NaHS (Sigma-Aldrich), cadmium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich), and nifedipine (Calbiochem) were obtained from commercial sources. All stock solutions were made fresh before the experiments. PAG stock solutions (5 mM) were made in HBSS, and pH was adjusted to ∼7.38. Desired concentrations of PAG were added to glomus cell culture plates to obtain a final concentration of either 50 or 100 μM. Stock solutions of NaHS (30 mM) were prepared in HBSS, with pH adjusted to 7.38, and were kept on ice. Desired concentrations of NaHS were added to the perfusate to obtain final concentrations of 30, 50, 100, and 300 μM immediately before the experiment. Given that NaHS is very unstable, the solutions were used within 1 h after its preparation.

Analysis of data.

Average data are presented as means ± SE. Statistical significance was assessed by ANOVA. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

CSE expression in primary cultures of rat glomus cells and the effects of hypoxia on CSE-mediated H2S generation.

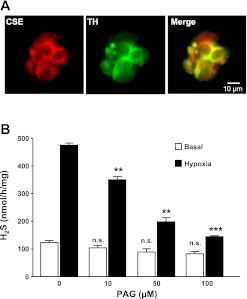

CSE-like immunoreactivity was seen in glomus cells dissociated from rat carotid bodies as evidenced by colocalization with tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), an established marker of these cells (Fig. 1A) (10, 19). H2S levels were determined in glomus cells under normoxia (Po2 ∼146 mmHg) and hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg). H2S levels increased by approximately fivefold in response to hypoxia (Fig. 1B). To determine whether CSE contributes to hypoxia-evoked H2S generation, cells were treated with increasing concentrations of PAG, an inhibitor of CSE (1, 29). PAG treatment attenuated hypoxia-evoked H2S generation in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas it had no significant effect on basal H2S levels under normoxia (P > 0.05; Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE) expression in rat carotid body glomus cells and effect of hypoxia on H2S generation. A: CSE expression in dissociated rat carotid body glomus cells. Cells were stained with antibodies specific for CSE or tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), a marker of glomus cells. B: levels of basal and hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg)-evoked H2S generation in rat glomus cells treated with increasing concentrations of dl-propargylglycine (PAG). Data are presented as means ± SE from five independent experiments. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s., not significant (P > 0.05).

Effect of blockade of H2S generation on hypoxia-evoked exocytosis from glomus cells.

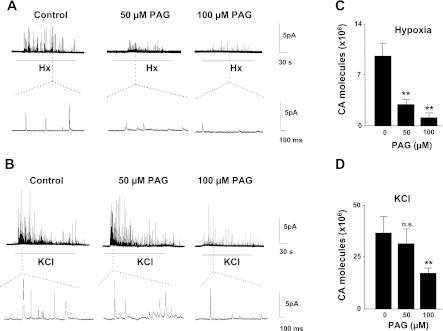

Catecholamine (CA) secretion from isolated glomus cells was determined by carbon-fiber amperometry (4, 27). Hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg) stimulated CA secretion, and this response was significantly attenuated in cells treated with 50 μM PAG (P < 0.01; Fig. 2, A and C). In striking contrast, CA secretion elicited by 40 mM KCl, a nonselective depolarizing stimulus, was not affected by 50 μM PAG (Fig. 2, B and D). PAG (50 μM) by itself had no effect on basal CA secretion (basal catecholamine secretion 105 molecules/min. Control, 3.8 ± 0.8; n = 21 cells; 50 μM PAG, 3.1 ± 0.8; n = 13 cells; P > 0.05). In cells treated with 100 μM PAG, hypoxia as well as KCl-evoked CA secretion was attenuated, indicating nonspecific effects of PAG at higher doses (2, A–D).

Fig. 2.

Effect of PAG, an inhibitor of CSE, on glomus cell secretory responses to hypoxia (Hx) and KCl. A and B: examples of hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg) and 40 mM KCl-evoked catecholamine (CA) secretion from control, 50 or 100 μM PAG-treated rat glomus cells. Horizontal bars represent the duration of the hypoxia or KCl challenges. Amperometric tracings on expanded time scale are shown in bottom panels. C and D: average data (means ± SE) showing the total number of CA molecules secreted during hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg) or KCl. Data from hypoxia experiments (C) were derived from 21 cells of vehicle control (0), 13 cells with 50 μM PAG, and 10 cells with 100 μM PAG. Results with KCl (D) were obtained from 14 cells of vehicle control (0), 12 cells with 50 μM PAG, and 11 cells with 100 μM PAG. **P < 0.01; n.s. = not significant (P > 0.05).

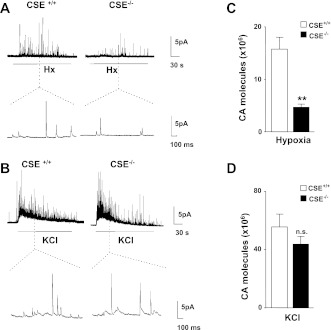

We recently reported that CSE is also expressed in glomus cells of the mouse carotid body and that hypoxia-evoked H2S generation was absent in carotid bodies from CSE−/− mice (22). To further assess the role of CSE-generated H2S, studies were performed on glomus cells from wild type (CSE+/+) and CSE−/− mice. Glomus cells from CSE+/+ mice responded to hypoxia with robust CA secretion. Hypoxia-evoked CA secretion was significantly attenuated in CSE−/− mice (Fig. 3, A and C). In striking contrast, glomus cells from both genotypes responded to KCl with comparable magnitude of CA secretion (Fig. 3, B and D).

Fig. 3.

Glomus cell secretory response to hypoxia and KCl in CSE+/+ and CSE−/− mice. A and B: examples illustrating CA secretion in response to hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg) (A) or 40 mM KCl (B) from glomus cells harvested from CSE+/+ and CSE−/− mice carotid bodies. Horizontal bars indicate the duration of hypoxia and KCl challenges. Amperometric tracings on expanded time scale are shown in bottom panels. C and D: average data (means ± SE) of the total CA molecules secreted during hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg; C) or KCl (D). Data from hypoxia experiments were derived from 14 CSE+/+ cells and 13 CSE−/− cells. Results with KCl were obtained from 16 CSE+/+ cells and 14 CSE−/− cells. **P < 0.01; n.s. = not significant (P > 0.05).

Effect of blockade of H2S generation on [Ca2+]i response of glomus cells.

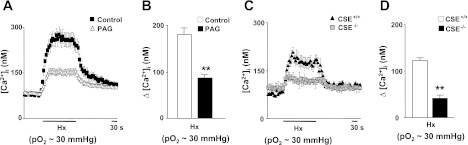

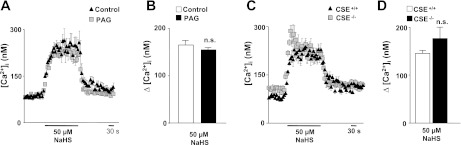

Elevation of [Ca2+]i is an obligatory step in hypoxia-evoked CA secretion from glomus cells (7, 27). Basal [Ca2+]i levels were not affected in PAG-treated glomus cells (control, 80 ± 12 nM; n = 47 cells; 50 μM PAG, 87 ± 10 nM; n = 51 cells). Hypoxia increased [Ca2+]i in glomus cells from rats and CSE+/+ mice (Fig. 4). [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia were significantly attenuated in PAG treated rat glomus cells and in CSE−/− mice (P < 0.01; Fig. 4). Brief (∼2.5 min) application of NaHS (50 μM), an H2S donor, increased [Ca2+]i in glomus cells, with a time course similar to hypoxia, and this response was unaffected by PAG or in CSE−/− mice (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Effect of blockade of endogenous H2S generation on glomus cell cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) responses to hypoxia. A and B: representative examples and average data of [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg) in control (n = 47 cells) and 50 μM PAG-treated rat glomus cells (n = 51 cells). C and D: representative examples and average data of hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg)-evoked [Ca2+]i responses in glomus cells from CSE+/+ (n = 18 cells) and CSE−/− mice (n = 20 cells). Horizontal bars in A and C represent the duration of hypoxic challenge. Ca2+ responses are analyzed as Δchanges, i.e., hypoxia minus baseline, and the data are presented as means ± SE. **P < 0.01.

Fig. 5.

Effect of exogenous application of H2S donor on [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cells. A–D: examples and average data illustrating [Ca2+]i responses to NaHS (50 μM) in rat glomus cells in control conditions (n = 35 cells) and after treatment with 50 μM PAG (n = 38 cells) (A and B) and in glomus cells from CSE+/+ (n = 15 cells) and CSE−/− mice (n = 17 cells) (C and D). Horizontal bars represent the duration of NaHS application. Ca2+ responses are analyzed as Δchanges, i.e., NaHS minus baseline, and the data are presented as means ± SE; n.s. = not significant (P > 0.05).

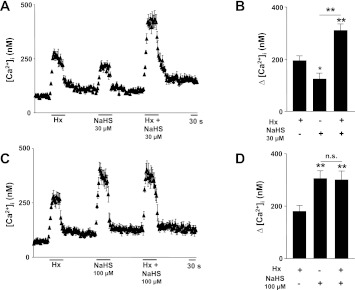

Effect of combined application of NaHS and hypoxia on [Ca2+]i in glomus cells.

The above results showed that H2S donor mimicked the effects of hypoxia on [Ca2+]i in glomus cells. We further examined whether the combined application of hypoxia and H2S produces synergistic effects on [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cells. To this end, [Ca2+]i responses were monitored in response to 30 μM NaHS (a concentration close to EC50 for H2S response) alone and in combination with hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg). As shown in Fig. 6, A and B, 30 μM NaHS caused a modest elevation of [Ca2+]i relative to hypoxia. Combined application of 30 μM NaHS plus hypoxia produced significantly greater elevation of [Ca2+]i than either stimulus alone (Fig. 6, A and B). On the other hand, 100 μM NaHS caused greater elevation of [Ca2+]i than hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg; Fig. 6, C and D). Combined application of 100 μM NaHS and hypoxia had no further additive effect on [Ca2+]i response of glomus cells (Fig. 6, C and D).

Fig. 6.

Effect of combined application of hypoxia and H2S donor on [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cells. A and B: examples and average data illustrating [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg), NaHS (30 μM), and combined application of both hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg) and NaHS (30 μM) in rat glomus cells (n = 22 cells). C and D: examples and average data illustrating [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg), NaHS (100 μM), and combined application of both hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg) and NaHS (100 μM) in rat glomus cells (n = 17 cells). Horizontal bar represents the duration of hypoxia and NaHS applications. Ca2+ responses were analyzed as Δchanges, i.e., stimulus minus baseline, and the data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; n.s. = not significant (P > 0.05).

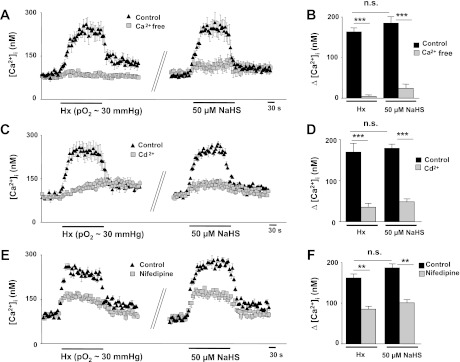

Extracellular Ca2+ is required for [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia and H2S.

Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space or, alternatively, release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores might give rise to the change in [Ca2+]i observed after challenging glomus cells with either hypoxia or NaHS. To assess the contribution of extracellular Ca2+, [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia and NaHS were determined in the presence of Ca2+-free medium (0 Ca2+ + 0.5 mM EGTA). [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia and NaHS were abolished in Ca2+-free medium (Fig. 7, A and B). Cadmium chloride (Cd2+; 300 μM), a broad spectrum voltage-gated Ca2+ channel blocker, significantly attenuated [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia and NaHS (Fig. 7, C and D). Nifedipine (10 μM), an L-type Ca2+ channel blocker, significantly reduced [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia and NaHS (Fig. 7, E and F).

Fig. 7.

Extracellular Ca2+ is required for [Ca2+]i elevation by hypoxia and NaHS. A, C, and E: examples illustrating [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg) and NaHS (50 μM) in rat glomus cells in control physiological solution or in the presence of Ca2+-free medium plus 0.5 mM EGTA (A), or 300 μM Cd2+ (C), or 10 μM nifedipine (E). Horizontal bars represent the duration of hypoxia or NaHS challenges. B, D, and F: average data (means ± SE) of the effects of Ca2+-free medium (B) (Hx, n = 39 cells; NaHS, n = 49 cells), or 300 μM Cd2+ (D) (Hx, n = 29 cells; NaHS, n = 18 cells), or 10 μM nifedipine (F) (Hx, n = 22 cells; NaHS, n = 25 cells) on [Ca2+]i responses of rat glomus cells to hypoxia and NaHS. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s. = not significant (P > 0.05).

NaHS at higher concentration (300 μM) produced a modest increase in [Ca2+]i compared with 50 μM NaHS, and this response persisted in Ca2+-free medium (Fig. 8, A and B). At higher concentrations, NaHS significantly reduced cell viability as determined by Trypan blue exclusion (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

Effect of high concentration of NaHS on [Ca2+]i responses and cell viability of glomus cells. A and B: example (A) and average data (means ± SE) (B) [Ca2+]i responses of rat glomus cells to 300 μM NaHS in the presence of Ca2+-containing (n = 41 cells) and Ca2+-free plus 0.5 mM EGTA-containing medium (n = 26 cells). Horizontal bar represents the duration of NaHS application. C: effect of NaHS on glomus cell viability assessed with Trypan blue (0.4%) staining. Average data (means ± SE) from five independent experiments are presented as percentage of glomus cells that were not stained by 0.4% Trypan blue in control (C) physiological solution (n = 159 cells) or 50 μM NaHS (n = 160 cells) and 300 μM NaHS (n = 156 cells). **P < 0.01; n.s. = not significant (P > 0.05) compared with controls.

DISCUSSION

The present study examined the role of the endogenous H2S generated by CSE in glomus cell responses to hypoxia. CA secretion evoked by low O2 was used as readout of hypoxic response of glomus cells. Our results demonstrate that primary cultures of glomus cells retain CSE expression and respond to hypoxia with increased generation of endogenous H2S. PAG, a CSE inhibitor (1, 29), not only prevented hypoxia-evoked H2S generation but also resulted in loss of hypoxia-evoked CA secretion. A similar loss of hypoxic response was also seen in glomus cells from CSE−/− mice. The above described effects were unique to hypoxia, because CA secretion by KCl was unaffected by PAG and in CSE−/− cells. We could not assess whether exogenous application of H2S mimics the effects of hypoxia on glomus cells, because the H2S donor interfered with CA detection by amperometry. We also tried to examine the effects of increased H2S production per se on CA secretion by treating glomus cells with increasing concentrations of l-cysteine, a substrate for CSE. Although biochemical measurements showed increased H2S levels in cells treated with l-cysteine, l-cysteine, like H2S donor, also interfered with CA detection by amperometry. Furthermore, the approach for measuring H2S generation employed in the present study did not allow us to correlate the time course of hypoxia-evoked H2S generation with CA secretion. Nonetheless, since PAG as well as genetic loss of CSE prevented endogenous H2S generation by hypoxia (22, and Fig. 1), we attribute the loss of hypoxic response to lack of endogenous H2S generation by low Po2.

How might hypoxia increase H2S levels in glomus cells? Hemeoxygenase-2 (HO-2), which generates carbon monoxide (CO), is expressed in glomus cells, and HO inhibitor increases H2S generation in wild type but not in CSE−/− carotid bodies (22, 23). These findings prompted us to propose that hypoxia-evoked H2S generation in the carotid body involves interaction of CSE with HO-2 (22). It is likely that a similar mechanism contributes to increased H2S levels by hypoxia in primary cultures of glomus cells as well. Recently, Fu et al. (8) reported that increased [Ca2+]i promotes H2S production via CSE activation. Since hypoxia also increased [Ca2+]i in glomus cells, it is also possible that activation of CSE by Ca2+, independent of interactions between HO-2 and CSE, might also contribute to H2S generation by low O2, a possibility that requires further investigation.

Besides CSE, CBS is another major enzyme for endogenous H2S generation. Aminooxyacetic acid (AOAA), a purported inhibitor of CBS, has been shown to attenuate carotid body response to hypoxia (15). However, AOAA is known to inhibit pyridoxal phosphate (PLP)-dependent enzymes including 4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase (GABA-T; 2) and increase GABA levels in tissues (28) and disrupt mitochondrial function (11). Since the carotid body sensory response to hypoxia is profoundly affected by GABA (31) and requires intact mitochondrial function (see 13 for ref.), it is uncertain whether the effects of AOAA on carotid body responses to hypoxia are due to inhibition of CBS-generated H2S or secondary to changes in GABA levels and/or mitochondrial function. Genetic disruption of CBS results in homocyst(e)inemia (30) and its consequences on the carotid body sensory activity are not known. Because of these limitations, we did not pursue examining the relative contribution of H2S generated by CBS to glomus cell response to hypoxia. Since both pharmacological (PAG) and genetic disruption of CSE function impaired glomus cell response to hypoxia, it is reasonable to conclude that H2S generated by CSE is a major contributor to glomus cell response to low O2.

An elevation of [Ca2+]i is critical for exocytosis (7, 27). Hypoxia increased [Ca2+]i in both rat and mouse glomus cells, and this response was markedly attenuated by PAG and in cells from CSE−/− mice. The impaired [Ca2+]i responses would account for the reduced CA secretion by hypoxia in PAG-treated cells and cells from CSE−/− mice. These observations suggest that endogenous H2S mediates the [Ca2+]i response to hypoxia. If this possibility is valid, then exogenous application of H2S should mimic the effects of low O2 on [Ca2+]i. Indeed, NaHS, a H2S donor, like hypoxia, caused prompt and reversible increases in [Ca2+]i with a comparable time course and magnitude of the response as shown in the present study (Fig. 5, A and B) and as reported recently by Buckler (3). Furthermore, [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia were pronounced in the presence of NaHS at a dose closer to EC50 but not with a higher dose of NaHS (Fig. 6, A–D). These observations suggest that both hypoxia and H2S utilize common mechanism(s) for elevating [Ca2+]i in glomus cells.

Several studies reported that voltage-gated Ca2+ entry mediates hypoxia-induced increases in [Ca2+]i (20, 24, 25). If H2S mediates the [Ca2+]i response to low O2, then H2S donors, like hypoxia, should activate voltage-gated Ca2+ entry. Supporting such a possibility are the findings that [Ca2+]i responses to NaHS or hypoxia were abolished in the presence of Ca2+-free medium as well as with the pan voltage-gated Ca2+ channel blocker Cd2+. These findings are consistent with a recent study (3). We therefore suggest that both stimuli activate voltage-gated Ca2+ entry. Of the various voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, L-type Ca2+ channels are implicated in glomus cell response to hypoxia (5, 25). Nifedipine, an L-type Ca2+ channel blocker, markedly reduced [Ca2+]i responses to NaHS as well as to hypoxia, indicating that H2S activates L-type Ca2+ channels. The activation of L-type Ca2+ channels might be secondary to a depolarization produced by inhibition of Ca2+-activated K+ and/or TASK-like background K+ currents in glomus cells by H2S (3, 26). The residual increase in [Ca2+]i evoked by both stimuli in the presence of nifedipine might be due to activation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels other than L-type, whose identity remains to be investigated.

It is noteworthy that at higher concentration, NaHS (300 μM) produced only a modest elevation of [Ca2+]i compared with 50 μM of NaHS, and decreased glomus cell viability. The elevation of [Ca2+]i produced by 300 μM NaHS was not affected by removal of extracellular Ca2+. These results suggest that the elevation of [Ca2+]i produced by high concentrations of NaHS seems to require mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ stores, possibly involving mitochondrion as suggested recently (3, 8).

Previous studies by us (22) and other investigators (15) have shown that endogenously generated H2S is critical for sensory excitation of the carotid body by hypoxia. This increase in the sensory activity could be due to actions of H2S on the afferent nerve endings and/or on glomus cells. The present study provides evidence for glomus cells as a major target of endogenous H2S and further demonstrates that it regulates Ca2+ signaling, which is an obligatory step in the transduction of the hypoxic stimulus to nerve encoded activity of the carotid body. Further studies, however, are needed to assess whether H2S also directly acts on the sensory nerve endings of the carotid body.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-76537, HL-90554, and HL-86493 (to N. R. Prabhakar) and U.S. Public Health Science Service Grant MH18501 (to S. H. Snyder). M. M. Gadalla is supported by Medical Scientist Training Program Award T32 GM007309.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

V.V.M., J.N., G.R., and G.K.K. performed the experiments; V.V.M., G.R., and G.K.K. analyzed the data; V.V.M., J.N., A.P.F., G.K.K., and N.R.P. interpreted the results of the experiments; V.V.M. and G.K.K. prepared the figures; J.N. and N.R.P. drafted the manuscript; J.N., A.P.F., M.M.G., S.H.S., and N.R.P. edited and revised the manuscript; N.R.P. conception and design of the research; N.R.P. approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This article is the topic of an Editorial Focus by Kimberly A. Smith and Jason X.-J. Yuan (24a).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abeles RH, Walsh CT. Acetylenic enzyme inactivators. Inactivation of gamma-cystathionase, in vitro and in vivo, by propargylglycine. J Am Chem Soc 95: 6124–6125, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beeler T, Churchich JE. Reactivity of the phosphopyridoxal groups of cystathionase. J Biol Chem 251: 5267–5271, 1976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buckler KJ. Effects of exogenous hydrogen sulphide on calcium signalling, background (TASK) K channel activity and mitochondrial function in chemoreceptor cells. Pflügers Arch 463: 743–754, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carpenter E, Hatton CJ, Peers C. Effects of hypoxia and dithionite on catecholamine release from isolated type I cells of the rat carotid body. J Physiol 523: 719–729, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cayzac SH, Rocher A, Obeso A, Gonzalez C, Riccardi D, Kemp PJ. Spermine attenuates carotid body glomus cell oxygen sensing by inhibiting L-type Ca2+ channels. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 175: 80–89, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fidone SJ, Zapata P, Stensaas LJ. Axonal transport of labeled material into sensory nerve ending of cat carotid body. Brain Res 124: 9–28, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fishman MC, Greene WL, Platika D. Oxygen chemoreception by carotid body cells in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82: 1448–1450, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu M, Zhang W, Wu L, Yang G, Li H, Wang R. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) metabolism in mitochondria and its regulatory role in energy production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 2943–2948, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hodges RD, King AS, King DZ, French EI. The general ultrastructure of the carotid body of the domestic fowl. Cell Tissue Res 162: 483–497, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karasawa N, Kondo Y, Nagatsu I. Immunohistocytochemical and immunofluorescent localization of catecholamine-synthesizing enzymes in the carotid body of the bat and dog. Arch Histol Jpn 45: 429–435, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kauppinen RA, Sihra TS, Nicholls DG. Aminooxyacetic acid inhibits the malate-aspartate shuttle in isolated nerve terminals and prevents the mitochondria from utilizing glycolytic substrates. Biochim Biophys Acta 930: 173–178, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kondo H, Iwanaga T, Nakajima T. Immunocytochemical study on the localization of neuron-specific enolase and S-100 protein in the carotid body of rats. Cell Tissue Res 227: 291–295, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar P, Prabhakar NR. Peripheral chemoreceptors: function and plasticity of the carotid body. Comprehensive Physiol: 141–219, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lever JD, Lewis PR, Boyd JD. Observations on the fine structure and histochemistry of the carotid body in the cat and rabbit. J Anat 93: 478–490, 1959 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Q, Sun BY, Wang XF, Jin Z, Zhou Y, Dong L, Jiang LH, Rong WF. A crucial role for hydrogen sulfide in oxygen sensing via modulating large conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Antioxid Redox Signal 12: 1179–1189, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonald DM. Peripheral chemoreceptors: structure-function relations of the carotid body. In: The Regulation of Breathing. Lung Biology in Health and Disease. New York: Dekker, 1981, p. 105–319 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morikawa T, Kajimura M, Nakamura T, Hishiki T, Nakanishi T, Yukutake Y, Nagahata Y, Ishikawa M, Hattori K, Takenouchi T, Takahashi T, Ishii I, Matsubara K, Kabe Y, Uchiyama S, Nagata E, Gadalla MM, Snyder SH, Suematsu M. Hypoxic regulation of the cerebral microcirculation is mediated by a carbon monoxide-sensitive hydrogen sulfide pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 1293–1298, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nurse CA. Localization of acetylcholinesterase in dissociated cell cultures of the carotid body of the rat. Cell Tissue Res 250: 21–27, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nurse CA, Fearon IM. Carotid body chemoreceptors in dissociated cell culture. Microsc Res Tech 59: 249–255, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Obeso A, Rocher A, Fidone S, Gonzalez C. The role of dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca2+ channels in stimulus-evoked catecholamine release from chemoreceptor cells of the carotid body. Neuroscience 47: 463–472, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olson KR, Healy MJ, Qin Z, Skovgaard N, Vulesevic B, Duff DW, Whitfield NL, Yang GD, Wang R, Perry SF. Hydrogen sulfide as an oxygen sensor in trout gill chemoreceptors. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R669–R680, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng YJ, Nanduri J, Raghuraman G, Souvannakitti D, Gadalla MM, Kumar GK, Snyder SH, Prabhakar NR. H2S mediates O2 sensing in the carotid body. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 10719–10724, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prabhakar NR, Dinerman JL, Agani FH, Snyder SH. Carbon monoxide: a role in carotid body chemoreception. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 1994–1997, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shirahata M, Fitzgerald RS. Dependency of hypoxic chemotransduction in cat carotid body on voltage-gated calcium channels. J Appl Physiol 71: 1062–1069, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24a.Smith KA, Yuan JX. H2S, a gasotransmitter for oxygen sensing in carotid body. Focus on “Endogenous H2S is required for hypoxic sensing by carotid body glomus cells.” Am J Physiol Cell Physiol (September 19, 2012). doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00307.2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Summers BA, Overholt JL, Prabhakar NR. Augmentation of L-type calcium current by hypoxia in rabbit carotid body glomus cells: evidence for a PKC-sensitive pathway. J Neurophysiol 84: 1636–1644, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Telezhkin V, Brazier SP, Cayzac S, Müller CT, Riccardi D, Kemp PJ. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits human BKCa channels. Adv Exp Med Biol 648: 65–72, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ureña J, Fernández-Chacón R, Benot AR, Alvarez de Toledo GA, López-Barneo J. Hypoxia induces voltage-dependent Ca2+ entry and quantal dopamine secretion in carotid body glomus cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 10208–10211, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wallach DP. Studies on the GABA pathway. I. The inhibition of gamma-aminobutyric acid-alpha-ketoglutaric acid transaminase in vitro and in vivo by U-7524 (amino-oxyacetic acid). Biochem Pharmacol 5: 323–331, 1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Washtien W, Abeles RH. Mechanism of inactivation of gamma-cystathionase by the acetylenic substrate analogue propargylglycine. Biochemistry 16: 2485–2491, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watanabe M, Osada J, Aratani Y, Kluckman K, Reddick R, Malinow MR, Maeda N. Mice deficient in cystathionine beta-synthase: animal models for mild and severe homocyst(e)inemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 1585–1589, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang M, Clarke K, Zhong H, Vollmer C, Nurse CA. Postsynaptic action of GABA in modulating sensory transmission in co-cultures of rat carotid body via GABA(A) receptors. J Physiol 587: 329–344, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]