Abstract

High Al resistance in buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench. cv Jianxi) has been suggested to be associated with both internal and external detoxification mechanisms. In this study the characteristics of the external detoxification mechanism, Al-induced secretion of oxalic acid, were investigated. Eleven days of P depletion failed to induce secretion of oxalic acid. Exposure to 50 μm LaCl3 also did not induce the secretion of oxalic acid, suggesting that this secretion is a specific response to Al stress. Secretion of oxalic acid was maintained for 8 h by a 3-h pulse treatment with 150 μm Al. A nondestructive method was developed to determine the site of the secretion along the root. Oxalic acid was found to be secreted in the region 0 to 10 mm from the root tip. Experiments using excised roots also showed that secretion was located on the root tip. Four kinds of anion-channel inhibitors showed different effects on Al-induced secretion of oxalic acid: 10 μm anthracene-9-carboxylic acid and 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonate had no effect, niflumic acid stimulated the secretion 4-fold, and phenylglyoxal inhibited the secretion by 50%. Root elongation in buckwheat was not inhibited by 25 μm Al or 10 μm phenylglyoxal alone but was inhibited by 40% in the presence of Al and phenylglyoxal, confirming that secretion of oxalic acid is associated with Al resistance.

Al toxicity is a serious agricultural problem in acid soils, which make up about 40% of the world's arable land (Foy et al., 1978). Al3+, the phytotoxic species, inhibits root growth and the uptake of water and nutrients, which ultimately results in a production decrease, although the toxicity mechanism is poorly understood (Kochian, 1995). On the other hand, some plant species and cultivars of the same species have developed strategies to avoid or tolerate Al toxicity. For the selection and breeding of plants resistant to Al toxicity, an economic and sustainable approach for improving crop production on acid soils, it is also useful to gain an understanding of the mechanisms used by plants for Al resistance.

The proposed mechanisms of Al resistance can be classified into exclusion mechanisms and internal tolerance mechanisms (Taylor, 1991; Kochian, 1995). The main difference between these two mechanisms is in the site of Al detoxification: symplasm (internal) or apoplasm (exclusion). The exclusion mechanism prevents Al from crossing the plasma membrane and entering the symplasm, reaching sensitive intracellular sites (Taylor, 1991). By contrast, the internal tolerance mechanism immobilizes, compartmentalizes, or detoxifies Al entering the symplasm.

One of the proposed exclusion mechanisms is the secretion of Al-chelating substances, because the chelated form of Al is less phytotoxic than the ionic form, Al3+ (Hue et al., 1986). Because some organic acids such as citric acid can form a stable complex with Al, their secretion has been reported to be involved in the exclusion mechanism. Miyasaka et al. (1991) presented evidence that an Al-resistant cultivar of snapbean (Phaseolus vulgaris) exuded higher levels of citric acid into the rhizosphere than an Al-sensitive cultivar in response to Al stress. Delhaize et al. (1993) used near-isogenic wheat lines differing in Al resistance at the Al-resistance locus (Alt 1) and found that Al-resistant genotypes excreted 5- to 10-fold more malic acid than Al-sensitive genotypes. After investigating a wide range of wheat genotypes differing in Al resistance, Ryan et al. (1995b) suggested that Al-induced secretion of malic acid is a general Al-resistance mechanism in wheat. Citric acid secretion was also found to be stimulated in an Al-resistant maize line (Pellet et al., 1995). Recently, Ma et al. (1997c) reported that specific secretion of citric acid was induced by Al in Cassia tora L., an Al-resistant species. In addition, transgenic tobacco and papaya plants have been altered genetically by introducing a citrate synthase gene from Pseudomonas aeruginosa in their cytoplasm (Fuente et al., 1997), and overproduction of citric acid resulted in increased Al resistance in these two plants. These results confirmed that the secretion of organic acids is related to Al resistance.

Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench. cv Jianxi) shows high Al resistance (Zheng et al., 1998). Ten days of intermittent exposure to Al (1 d in 0.5 mm CaCl2 containing 50 μm AlCl3 at pH 4.5 alternating with 1 d in nutrient solution without Al) hardly affected root growth of the buckwheat but inhibited root growth by 65% in an Al-sensitive cultivar of wheat (Tritium aestivum L. cv Scout 66) and by 25% to 50% in two cultivars of oilseed rape (Brassica rapus L. cvs 94008 and H166), two cultivars of oat (Avena sativa L. cvs Tochiyutaka and Heoats), and an Al-tolerant cultivar of wheat (cv Atlas 66). Recently, we found that oxalic acid, the simplest dicarboxylic acid, was secreted by the roots of buckwheat in response to Al stress (Ma et al., 1997b). Furthermore, Al was found to be accumulated in the leaves without toxicity. Oxalic acid is known to be a strong Al chelator (Hue et al., 1986), and therefore both external and internal detoxification of Al by oxalic acid may be involved in the high Al resistance of buckwheat. In the present study the characteristics of Al-induced secretion of oxalic acid were investigated in terms of the specificity, location, and effects of anion-channel inhibitors. The role of oxalic acid in detoxifying Al is also discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench. cv Jianxi) seeds were collected from an acid-soil area of southern China. Seeds were soaked in distilled water overnight and then germinated on a net tray in the dark at 25°C. On d 2 the tray was put on a plastic container filled with 0.5 mm CaCl2 solution at pH 4.5. The solution was renewed every day. On d 4 or 5, seedlings of similar size were transplanted into a 1-L plastic pot (eight seedlings per pot) containing aerated nutrient solution. One-fifth-strength Hoagland solution was used, which contained the macronutrients KNO3 (1.0 mm), Ca(NO3)2 (1.0 mm), MgSO4 (0.4 mm), and (NH4)H2PO4 (0.2 mm) and the micronutrients NaFeEDTA (20 μm), H3BO3 (3 μm), MnCl2 (0.5 μm), CuSO4 (0.2 μm), ZnSO4 (0.4 μm), and (NH4)6Mo7O24 (1 μm). The solution was adjusted to pH 4.5 with 1 m HCl and renewed every other day. After 8 to 10 d of culture in the above-described nutrient solution, the plants were subjected to the treatments described below. Plants were grown in a controlled-environment growth cabinet (TGE-9 h-S, TABAI Espec, Hiroshima, Japan) with a 14-h/25°C day and a 10-h/20°C night regime and a light intensity of 40 W m−2. Each experiment was conducted three times.

Al Resistance in Buckwheat

To confirm the Al resistance of buckwheat, the effect of Al treatment on root elongation was investigated. An Al-tolerant cultivar of wheat (Triticum aestivum L. cv Atlas 66), was used as a reference. Three-day-old seedlings of buckwheat or wheat, prepared as described above, were exposed to a 0.5 mm CaCl2, pH 4.5, solution with 25 μm AlCl3 or without Al. Ten replicates were made for each treatment. Root lengths were measured with a ruler before and after treatments (16 h).

Collection of Root Exudates and Treatment Solutions

Before collection of root exudates, the roots were cleaned by placing them in 0.5 mm CaCl2 at pH 4.5 overnight. To avoid interaction between Al and other nutrients such as P, a simple salt solution containing 0.5 mm CaCl2 was used as the basal treatment. The Al solution consisted of 50 μm AlCl3, except in pulse treatment and excised-root-tip experiments, when the concentration of AlCl3 was 150 μm. The pH of all solutions was adjusted to 4.5 with 1 m HCl.

To check the effect of the lack of aseptic conditions on the concentration of oxalic acid in root exudates, the following methods were used: First, roots were exposed to the Al solution for 6 h and then removed from the solution. At 0, 3, 7, and 24 h after the collection of root exudates, the concentration of oxalic acid was determined by HPLC as described below. Second, oxalic acid (3 μmol L−1) was added to the root exudates collected by exposing the roots to the solution without Al for 6 h, and the concentration of oxalic acid was monitored at different times as described above.

Specificity Studies

To investigate whether the secretion of oxalic acid is specific to Al stress, the secretion induced by Al stress was compared with that induced by P deficiency and La3+ exposure. Twelve-day-old seedlings prepared as described above were grown in the above-described nutrient solution devoid of P. Root exudates were collected for 6 h every other day by immersing the seedlings in 0.5 mm CaCl2 solution at pH 4.5. On d 12 after P depletion, the seedlings were immersed in the Al-treatment solution and the root exudates were collected for 6 h. Treatment with La3+ was performed by exposing the seedlings to 0.5 mm CaCl2 solution containing 50 μm LaCl3 (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan), and root exudates were collected for 6 h. Seedlings of the same age were also exposed to Al treatment.

A pulse treatment was conducted by first exposing the seedlings to 0.5 mm CaCl2 solution containing 150 μm AlCl3, pH 4.5, for 3 h and then to 0.5 mm CaCl2 solution, pH 4.5, without Al. Root exudates were collected 0 to 3, 3 to 7, 7 to 11, and 27 to 31 h after treatment.

Location of Secretion Site

To determine the location of oxalic acid secretion from the roots, two different methods were used with excised roots and intact roots. The amount of secretion from excised roots was compared between sections 0 to 5 and 5 to 10 mm from the root tip according to the method of Ryan et al. (1995a), with some modifications. One hundred segments for each measurement were collected in a 9-cm Petri dish containing 0.5 mm CaCl2 solution at pH 4.5 (control solution) with three replicates. The Petri dish was placed on a shaker (60 rpm) for 30 min. The root segments were washed with 20 mL of the same solution three times to remove any oxalic acid released from the wounded tissue and then transferred into a 15-mL plastic centrifuge tube containing the control solution. Treatment was initiated by replacing the solution (10 mL) with 0.5 mm CaCl2 solution containing 150 μm Al, pH 4.5, or control solution, and the tube was placed on a shaker (60 rpm). After 3 h the root exudate was collected. Endogenous soluble oxalic acid in different sections of the roots was extracted three times with distilled water at 55°C. The extracts were applied to cation- and anion-exchange resins as described below.

A nondestructive technique was developed to locate the site of secretion by modification of the method for determining Al-chelating activity reported by Ma et al. (1997c). Chromatography filter paper (no. 50, Advantec, Tokyo, Japan; 10 × 5 cm) was soaked in AlCl3 solution prepared by mixing 25 mL of 5 mm AlCl3, 4 mL of 2 m HCl, 67 mL of distilled water, and 120 mL of acetone. The paper was then immersed in phosphate buffer solution, pH 6.86 (Wako, Tokyo, Japan), for 3 min, followed by washing in deionized water three times to remove excess phosphate solution. The paper was then placed onto a layer of sponge (10 × 8 × 1 cm). Fifteen seedlings previously exposed to 0.5 mm CaCl2 solution containing 0 or 150 μm Al at pH 4.5 for 3 h were arranged on the paper. The root tips were placed on the same line and then covered by half of the paper. Another sponge (8 × 8 × 1 cm) was placed on the top and then the plants were incubated in a growth chamber at 25°C. After 8 h the seedlings were removed and the paper was washed in deionized water for 1 min. Finally, the paper was placed in pyrocatechol violet solution (37.5 mg dissolved in 100 mL of pH 5.6 acetate buffer) (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) for 3 min and washed in deionized water for approximately 2 min to remove excess dye, and photographs were taken on Fuji (Tokyo, Japan) 400 color film.

To estimate the amount of oxalic acid secreted, a solution of 5 μL of oxalic acid (1–4 mm) was spotted on the chromatography filter paper and assayed by the same procedures as described above.

Effect of Anion-Channel Inhibitors

To examine the effect of four anion-channel inhibitors on Al-induced secretion of oxalic acid, roots were treated with a solution containing 50 μm AlCl3 in 0.5 mm CaCl2 and 10 μm NIF (Sigma) or A-9-C (Aldrich) dissolved in ethanol or PG (Katayama Chemical, Osaka, Japan) or DIDS (Dojindo) dissolved in distilled water. Root exudates were collected for 6 h during the treatment.

The effect of PG on the root elongation of buckwheat was investigated in the presence and absence of Al. Three-day-old seedlings of similar size were selected and subjected to the following treatments for 16 h in 0.5 mm CaCl2 solution at pH 4.5: control (−Al), 10 μm PG, 25 μm Al (+Al), and 10 μm PG plus 25 μm Al. The root length was measured with a ruler before and after treatment.

Determination of Organic Acids

The root exudates and root extracts were passed through a cation-exchange column (16 × 14 mm) filled with 5 g of Amberlite IR-120B resin (H+ form, Muromachi Chemical, Tokyo, Japan), followed by an anion-exchange column (16 × 14 mm) filled with 2 g of Dowex 1X8 resin (100–200 mesh, format form) in a cold room. The organic acids retained on anion-exchange resin were eluted by 1 m HCl, and the eluate was concentrated to dryness by a rotary evaporator (40°C). After the residue was redissolved in dilute HClO4 solution, pH 2.1, the concentration of organic acids was analyzed by HPLC (Ma et al., 1997c)

Bioassay of Toxicity of Different Al-Oxalate Complexes

The toxicity of Al-oxalate complexes with different ratios of Al to oxalic acid was assayed using corn (Zea mays L. cv Golden Cross Bantam). Seeds were soaked in water for 10 h and then germinated on moist filter paper in an incubator at 30°C. After 1 d the seedlings were transplanted into a net tray containing 100 μm CaCl2 solution at pH 4.5 in a growth chamber under the following conditions: 25°C day and 20°C night, 65% RH, light intensity 40 W m−2, and a 14-h photoperiod. After a further 2 d seedlings of similar size were selected and subjected to the following treatments in 100 μm CaCl2 solution at pH 4.5 (six replicates): (a) −Al (control, no Al addition), (b) +Al (20 μm as AlCl3), (c) +Al-oxalate at a 2:1 molar ratio, (d) +Al-oxalate at 1:1, and (e) +Al-oxalate at 1:2. The Al concentration in all treatment solutions was adjusted to 20 μm. Different Al-oxalate complexes were prepared by mixing AlCl3 and sodium oxalate at different molar ratios. Root length was measured with a ruler before and after treatment. The treatment period was 22 h.

RESULTS

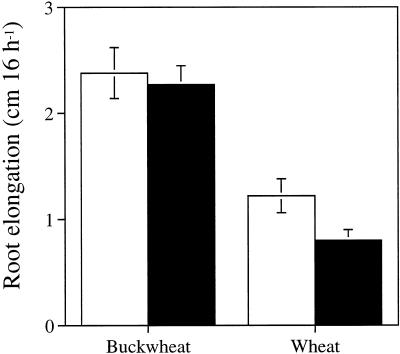

To confirm Al resistance of buckwheat, the effect of Al on root elongation was compared between buckwheat and an Al-tolerant cultivar of wheat, Atlas 66 (Fig. 1). Twenty-five-micromolar Al treatment hardly inhibited the root elongation of buckwheat but inhibited the root elongation of cv Atlas 66 by about 35% during 16 h. This result was consistent with those obtained in relatively long-term treatment of buckwheat with Al (Zheng et al., 1998), which showed high Al resistance.

Figure 1.

Effect of Al on root elongation in buckwheat and wheat. Three-day-old seedlings were exposed to 0.5 mm CaCl2 solution, pH 4.5, containing no Al (white bars) or 25 μm AlCl3 (black bars) for 16 h. Error bars represent ±sd (n = 10).

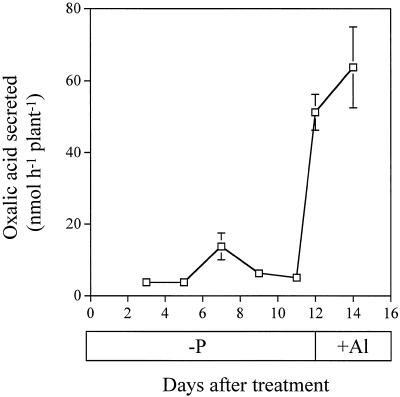

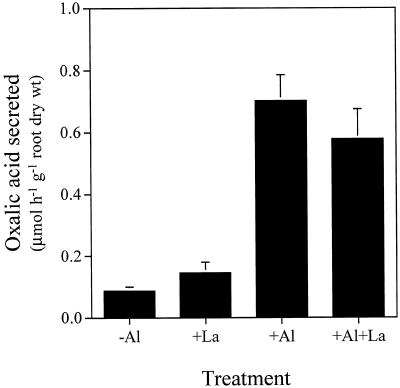

One of the mechanisms responsible for this high Al resistance has been suggested to be the secretion of oxalic acid from the roots (Ma et al., 1997b). For collection of root exudates in the present study, although the plants were not grown under aseptic conditions, careful attention was always paid to keeping the roots clean by frequent renewal of solution and by immersing the roots in Ca solution overnight before the collection of root exudates. By monitoring the concentration of oxalic acid in the root exudates (both −Al and +Al) at different times, we found that the lack of aseptic conditions did not affect the concentration of oxalic acid (data not shown). The specificity of Al-induced secretion of oxalic acid was investigated by comparing it with the root's responses to P deficiency and La3+ treatment. Oxalic acid in root exudates was monitored every other day after the initiation of P-deficiency treatment, but no significant amount was secreted up to 11 d (Fig. 2). When Al was added to the P-deficient roots on d 12 after the treatment, a significant amount of oxalic acid was secreted. Exposure to 50 μm La3+ did not induce significant secretion of oxalic acid (Fig. 3), whereas Al at the same concentration induced secretion of oxalic acid at 0.70 ± 0.08 μmol h−1 g−1 root dry weight. Combined treatment with Al3+ and La3+ did not affect the secretion of oxalic acid induced by Al.

Figure 2.

Effect of P deficiency followed by Al treatment on the secretion of oxalic acid by buckwheat roots. Ten-day-old seedlings were grown in nutrient solution devoid of P, and root exudates were collected every other day in 0.5 mm CaCl2 solution at pH 4.5 for 6 h. On d 12 and 14 after P deficiency, the roots were exposed to 50 μm Al solution, and the root exudates were collected for 6 h. After passage of the root exudates through a cation-exchange resin column followed by an anion-exchange resin column, the anionic fraction was eluted using 1 m HCl and concentrated. Organic acids were analyzed by HPLC. Error bars represent ±sd (n = 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of La3+ and Al3+ on the secretion of oxalic acid by buckwheat roots. Seedlings were exposed to 0.5 mm CaCl2 solution, pH 4.5, containing 50 μm AlCl3, 50 μm LaCl3, or both. After 6 h the root exudates were collected and organic acids were analyzed as described in Figure 1. Error bars represent ±sd (n = 3).

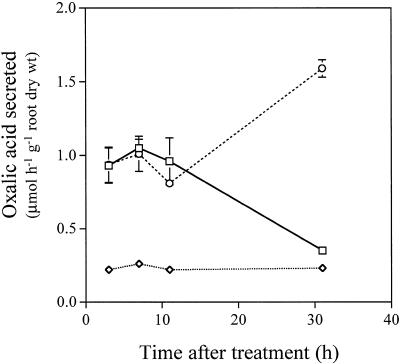

A 3-h pulse with 150 μm Al induced secretion of oxalic acid at 0.93 ± 0.12 μmol h−1 g−1 root dry weight during the first 3 h (Fig. 4). This level was maintained for 8 h in control solution without Al and then gradually decreased to the control level (−Al). In contrast, roots exposed to Al continued to secrete oxalic acid at a high level (Fig. 4). There are two possibilities for the pulse result. One is that Al might activate some biochemical process such that the secretion of oxalic acid was able to continue for several hours regardless of the Al concentration in the external solution or in the cell wall. The other is that when the roots were transferred from the Al solution to the Al-free solution, sufficient Al was left in the cell wall to trigger the secretion of oxalic acid for several hours. Since the roots were rinsed with 0.5 mm Ca solution, pH 4.5, several times and the solution was changed twice with the Ca solution during the collection of root exudates after pulse treatment, it is unlikely that sufficient Al was left in the cell wall.

Figure 4.

Effect of a 3-h pulse of 150 μm Al on the secretion of oxalic acid (□). Seedlings were exposed to 0.5 mm CaCl2 solution, pH 4.5, containing 150 μm AlCl3 for 3 h and subsequently to 0.5 mm CaCl2 solution, pH 4.5, without Al. Root exudates were collected during the periods 0 to 3, 3 to 7 , 7 to 11, and 27 to 31 h. For comparison, exudates of roots continuously exposed to 150 μm Al (○) or 0 μm (⋄) were also collected at the same interval. Organic acids were analyzed as described in Figure 1. Error bars represent ±sd (n = 3).

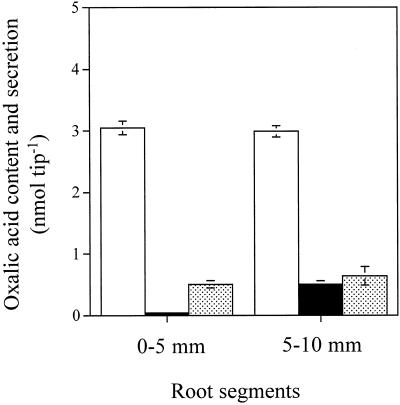

The concentration of oxalic acid was similar in both the 0- to 5- and the 5- to 10-mm sections in excised roots (Fig. 5). When the 0- to 5-mm root segments were exposed to Al solution, a significant amount of oxalic acid was detected in the treatment solution compared with those exposed to control solution without Al (Fig. 5). A high amount of oxalic acid was released from the 5- to 10-mm root segments regardless of Al treatment. Only one peak corresponding to oxalic acid was observed on the HPLC chart in the exudates from the 0- to 5-mm root segments, whereas several peaks were observed in the exudates from 5- to 10-mm segments. This suggests that the high release of oxalic acid from the 5- to 10-mm segments resulted from wounded tissues, although the segments were washed three times with control solution before treatment. In net amount of oxalic acid secreted (the −Al treatment value subtracted from the value for +Al treatment), the amount secreted from the 0- to 5-mm section (0.46 nmol tip−1) was 3 times more than that from the 5- to 10-mm section (0.15 nmol tip−1). About 15.1 and 5.0% of soluble oxalic acid in the 0- to 5- and 5- to 10-mm segments were secreted during 3 h, respectively (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Al-induced secretion of oxalic acid from a different section of buckwheat roots. Excised root segments 0 to 5 and 5 to 10 mm from root tips were incubated in 0.5 mm CaCl2 solution, pH 4.5, containing 0 or 150 μm AlCl3 after washing. After 3 h the root exudates were collected. Soluble oxalic acid in the 0- to 5- and the 5- to 10-mm root segments were extracted with distilled water at 55°C. Organic acids were analyzed as described in Figure 1. Shown are the oxalic acid content in roots (white bars), oxalic acid excreted by the roots not treated with Al (black bars), and oxalic acid secreted by roots treated with Al (shaded bars). Error bars represent ±sd (n = 3).

To avoid the release of organic acid from wounded tissue of excised roots, a nondestructive method was developed to determine the site of the secretion using intact roots. This method is based on the precipitation between AlCl3 and P at a neutral pH and the subsequent reaction of this Al-P complex with pyrocatechol violet (Ma et al., 1997c). The oxalic acid secreted by the roots chelates Al from the Al-P complex, and Al is removed by washing from the filter paper, resulting in a white spot. A white spot was observed when the roots were exposed to Al previously but not in the roots without Al treatment (Fig. 6). The secretion position was limited to 10 mm from the root tip. The amount of oxalic acid secreted was estimated to be 0.67 nmol root−1 from the standard solution of oxalic acid (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Location of secretion of oxalic acid (OX) along buckwheat roots. Fifteen roots exposed to 0 or 150 μm Al for 3 h were placed on the filter paper. After 8 h the amount of oxalic acid was assayed by the method described in Methods. For quantification, 5 μL of a 1- to 4-mm oxalic acid solution was spotted onto the filter paper and assayed by the same procedures as intact roots (top).

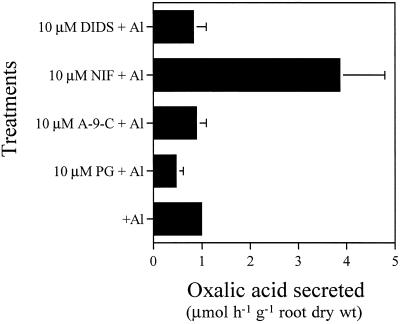

The effect of different anion-channel inhibitors on the secretion of oxalic acid in the presence of Al was examined. Neither DIDS nor A-9-C affected the Al-induced secretion of oxalic acid (Fig. 7). However, PG decreased the amount of oxalic acid secreted by about 50%. It is noteworthy that the amount of oxalic acid secreted was enhanced 4-fold by NIF.

Figure 7.

Effect of anion-channel inhibitors on Al-induced secretion of oxalic acid. Seedlings were exposed to 0.5 mm CaCl2 solution, pH 4.5, containing 50 μm Al in the presence or absence of each inhibitor (10 μm). After 6 h root exudates were collected, and organic acids were analyzed as described in Figure 1. Error bars represent ±sd (n = 3).

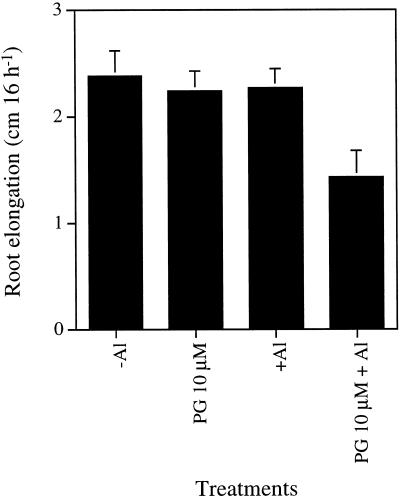

Root elongation of buckwheat root during 16 h was not inhibited by either PG (10 μm) or Al (25 μm) addition alone (Fig. 8). However, when the roots were exposed to the Al solution in the presence of PG, the root elongation was inhibited by 40%.

Figure 8.

Combined effect of Al and PG on root elongation in buckwheat. Seedlings were exposed to 0.5 mm CaCl2 solution, pH 4.5, containing no Al (−Al), 25 μm Al (+Al), 10 μm PG, or 25 μm Al plus 10 μm PG for 16 h. Error bars represent ±sd (n = 10).

Twenty-micromolar Al3+ inhibited root elongation of corn by about 60% during 22 h (Fig. 9), and Al-oxalate at a 2:1 ratio showed the same extent of toxicity. However, when the ratio of Al to oxalic acid changed to 1:1 and 1:2, the inhibition of root elongation was alleviated, with almost no inhibition at the 1:2 ratio.

Figure 9.

Effect of different molar ratios of Al to oxalic acid on the root elongation of corn. The Al concentration was 20 μm in 0.1 mm CaCl2 solution. Seedlings were exposed to different treatment solutions for 22 h. Error bars represent ±sd (n = 6).

DISCUSSION

Buckwheat shows high Al resistance compared with other species such as wheat, rape, and radish (Fig. 1; Zheng et al., 1998). One of the mechanisms responsible for its high resistance is the secretion of oxalic acid (Ma et al., 1997b) that occurs within 30 min after Al exposure and increases with increasing external Al concentration. In the present study the characteristics of such Al-induced secretion of oxalic acid was investigated. To examine the specificity of secretion, the response of roots to P deficiency and La treatments was compared with the response to Al treatment. La, which has the same charge as Al, is also reported to be toxic to plants (Bennet and Breen, 1992). It inhibits root elongation in both rice and pea more strongly than Al does (Ishikawa et al., 1996). On the other hand, secretion of organic acids has been reported to be a response of plants to P deficiency. White lupin and alfalfa secrete citric acid in response to P deficiency (Gardner et al., 1983; Lipton et al., 1987). Because Al is easily precipitated with P, organic acid secretion may be caused indirectly by Al-induced P deficiency (Miyasaka et al., 1991). However, the results have clearly indicated that neither P deficiency nor La addition induced significant secretion of oxalic acid (Figs. 2 and 3), suggesting that the secretion of oxalic acid is a specific response to Al stress. One day of P deficiency also failed to induce secretion of malic acid in wheat (Delhaize et al., 1993). In Cassia tora L., neither P deficiency nor La and Yb induced secretion of citric acid (Ma et al., 1997c). All of these findings indicate that the secretion of organic acids induced by Al is a response different from that to P deficiency. Usually, induction of organic acid secretion by P deficiency takes longer (more than 10 d; Johnson et al., 1996), but Al-induced secretion of organic acid occurs within several hours (Ryan et al., 1995a; Ma et al., 1997c).

Secretion of citric acid and malic acid has been reported to be an important resistance mechanism for Al toxicity (Miyasaka et al., 1991; Delhaize et al., 1993; Pellet et al., 1995; Ma et al., 1997c). However, it is unknown whether the amount of organic acids secreted is sufficient to detoxify Al. The primary site of Al toxicity is localized to the root apex (Ryan et al., 1993); therefore, it is a prerequisite to protect the root apex from Al injury. In wheat and corn the secretion of organic acids was localized to the root apex using the divided-root-chamber technique (Delhaize et al., 1993; Pellet et al., 1995). Using excised roots and a nondestructive method, we also showed that the secretion site of oxalic acid was localized to the root apex (0–10 mm from root tip; Figs. 5 and 6). Some attempts have been made to estimate the concentration of organic acids at the root surface based on data concerning organic acid efflux in the bulk solution. However, such estimation is very difficult because there are many related factors, such as the thickness of the unstirred layer, the length of root apex that should be protected, the diffusion coefficient, mucilage, and so on (Ryan et al., 1995b). In the present study we used an anion-channel inhibitor to demonstrate that the secretion of oxalic acid is associated with Al resistance in buckwheat. One of the anion-channel inhibitors, PG, was found to inhibit secretion of oxalic acid (Fig. 7). When PG or Al alone was added to the solution, the root elongation of buckwheat was not inhibited, but when roots were exposed to Al in the presence of PG, the root elongation of buckwheat was inhibited by 40% (Fig. 8). This result indicates that the secretion of oxalic acid contributes to high Al resistance in buckwheat.

In the Al-resistant genotype of wheat, malic acid was secreted from the root apex in response to Al stress (Delhaize et al., 1993), and this secretion was hypothesized to be through an anion channel located on the plasma membrane (Ryan et al., 1995a). In excised wheat roots, the anion-channel inhibitors NIF and A-9-C inhibited malic acid secretion, whereas DIDS had no effect (Ryan et al., 1995a). Recently, the same investigators reported that an anion channel in the apical cells of wheat roots was activated by Al3+ but not by La3+ (Ryan et al., 1997). In the present study we examined the effects of four kinds of anion-channel inhibitors on the secretion of oxalic acid in intact roots. One of them, PG, inhibited the secretion of oxalic acid, but DIDS and A-9-C had no effect on oxalic acid secretion (Fig. 7). NIF stimulated the secretion of oxalic acid. Moreover, the amount of secretion was increased with increasing external NIF concentrations (data not shown). We checked the secretion of oxalic acid when NIF was added alone (since NIF probably caused leakage of organic acids from roots), but none was detected. This result suggests that some interactions among Al, NIF, and anion channels caused enhancement of oxalic acid secretion, although the mechanism is not clear.

Oxalic acid can form three species of complexes with Al depending on its concentration. The stability constants for 1:1, 1:2, and 1:3 complexes are 5.0, 9.3, and 12.4, respectively (Nordstrom and May, 1996). The bioassay experiment showed that the 1:2 complex of Al-oxalate was nonphytotoxic for corn (Fig. 9). The Al-citrate complex with a 1:1 ratio was found to be nontoxic to the root growth of corn using the same assay system (Ma et al., 1997a). The Al-citrate (1:1) complex has a stable constant of 10.72, which is close to that of the 1:2 Al-oxalate complex. These findings suggest that both the concentration and stability constant of a chelator are important in detoxifying Al.

In conclusion, we found that the secretion of oxalic acid was a specific response to Al stress in buckwheat roots. This secretion occurred at the root apex and was associated with high Al resistance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful to Dr. Ren Fang Sheng at the Soil Research Institute (Academic Sinica of China) for providing buckwheat seeds.

Abbreviations:

- A-9-C

anthracene-9-carboxylic acid

- DIDS

4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonate

- NIF

niflumic acid

- PG

phenylglyoxal

Footnotes

This study was supported in part by a grant-in-aid for Scientific Research, for Encouragement of Young Scientists, for Creative Basic Research, for Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Fellows, and for Scientific Research on Priority Areas from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan, by a Sunbor grant, and by the Ohara Foundation for Agricultural Sciences.

LITERATURE CITED

- Bennet RJ, Breen CM. The use of lanthanum to delineate the aluminum signalling mechanisms functioning in the roots of Zea mays L. Environ Exp Bot. 1992;32:365–376. [Google Scholar]

- Delhaize E, Ryan PR, Randall PJ. Aluminum tolerance in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). II. Aluminum-stimulated excretion of malic acid from root apices. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:695–702. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.3.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foy CD, Chaney RL, White MC. The physiology of metal toxicity in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1978;29:511–566. [Google Scholar]

- Fuente JM, Ramirez-Rodriguez V, Cabrera-Ponce JL, Herrera-Estrella L. Aluminum tolerance in transgenic plants by alteration of citrate synthesis. Science. 1997;276:1566–1568. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5318.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner WK, Barber DA, Parberry DG. The acquisition of phosphorus by Lupinus albus L. III. The probable mechanism by which phosphorus movement in soil/root interface is enhanced. Plant Soil. 1983;70:107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Hue NV, Craddock GR, Adams F. Effect of organic acids on aluminum toxicity in subsoils. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 1986;50:28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa S, Wagatsuma T, Ikarashi T. Comparative toxicity of Al3+, Yb3+ and La3+ to root-tip cells differing in tolerance to high Al3+ in terms of ionic potentials of dehydrated trivalent cations. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 1996;42:613–625. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JF, Vance CP, Allan D. Phosphorus deficiency in Lupinus albus. Altered lateral root development and enhanced expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:31–41. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KochianLV Cellular mechanisms of aluminum toxicity and resistance in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1995;46:237–260. [Google Scholar]

- Lipton DS, Blanchar RW, Blevins DG. Citrate, malate, and succinate concentration in exudates from P-sufficient and P-stressed Medicago sativa L. seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1987;85:315–317. doi: 10.1104/pp.85.2.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma JF, Hiradate S, Nomoto K, Iwashita T, Matsumoto H. Internal detoxification mechanism of Al in hydrangea. Identification of Al form in the leaves. Plant Physiol. 1997a;113:1033–1039. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.4.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma JF, Zheng SJ, Hiradate S, Matsumoto H. Detoxifying aluminum with buckwheat. Nature. 1997b;390:569–570. [Google Scholar]

- Ma JF, Zheng SJ, Matsumoto H. Specific secretion of citric acid induced by Al stress in Cassia tora L. Plant Cell Physiol. 1997c;38:1019–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Miyasaka SC, Bute JG, Howell RK, Foy CD. Mechanism of aluminum tolerance in snapbean, root exudation of citric acid. Plant Physiol. 1991;96:737–743. doi: 10.1104/pp.96.3.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom DK, May HM. Aqueous equilibrium data for mononuclear aluminum species. In: Sposito G, editor. Environment Chemistry of Aluminum. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1996. pp. 39–80. [Google Scholar]

- Pellet DM, Grunes DL, Kochian LV. Organic acid exudation as an aluminum-tolerance mechanism in maize (Zea mays L.) Planta. 1995;196:788–795. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan PR, Delhaize E, Randall PJ. Characterisation of Al-stimulated efflux of malate from the apices of Al-tolerant wheat roots. Planta. 1995a;196:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan PR, Delhaize E, Randall PJ. Malate efflux from root apices and tolerance to aluminum are highly correlated in wheat. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1995b;22:531–536. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan PR, DiTomaso JM, Kochian LV. Aluminum toxicity in roots: an investigation of spatial sensitivity and the role of the root cap. J Exp Bot. 1993;44:437–446. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan PR, Skerrett M, Findlay GP, Delhaize E, Tyerman SD. Aluminum activates an anion channel in the apical cells of wheat roots. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6547–6552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor GJ. Current views of the aluminum stress response: the physiological basis of tolerance. Curr Top Plant Biochem Physiol. 1991;10:57–93. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng SJ, Ma JF, Matsumoto H (1998) Continuous secretion of organic acid is related to aluminum resistance in relatively long-term exposure to aluminum stress. Physiol Plant (in press)