Abstract

Consider a feature of a stimulus (such as color, luminance or spatial frequency) that changes over time along a continuum. When a second stimulus is briefly pulsed with the same feature value as the first stimulus, the two stimuli are not perceived to match. Instead, the continuously changing stimulus is perceived to be farther ahead on the feature continuum than the pulsed stimulus (Sheth, Nijhawan, & Shimojo, Nat. Neurosci., 3, 489, 2000). This shift is quantified by the amount of time ahead on the changing continuum, which is different for various types of features. A basic question is how our percepts are affected when an object has two continuously changing features (such as color and orientation) with different magnitudes of time ahead. This was addressed using a bar continuously changing in both color and orientation. Even though the two features were part of the same object, each feature maintained a distinctly different time ahead. This implies that observers perceived at each moment a combination of color and orientation that never was presented to the eye.

INTRODUCTION

Perception of the external world seems seamless and whole. This unified perceptual experience puzzled many researchers. W. James wrote “How can many consciousnesses be at the same time one consciousness [1]?” Specifically, how can different sensory aspects be experienced together in a unified percept? Integrating the features of an object into a unified whole has been called the “binding problem” [2]. Evidence for a binding process is supported by anatomical and physiological discoveries showing that the visual system consists of largely independent subsystems that mediate different visual features: color, form, motion, and binocular disparity [3–5].

The most convincing evidence for a binding problem comes from psychophysical experiments demonstrating illusory conjunctions [6]. Consider several letters with different colors flanked by two black digits. The stimuli are presented briefly, and the observer’s primary task is to report the two digits in the periphery. Secondarily, the observer reports the letters of different colors. Observers sometimes report perceiving a letter in view with a color in view but not a combination presented together [6]. This wrong combination of features, presented in two different objects at separate locations, is called illusory conjunction. Results support the view that attention acts as the “glue” for correctly binding features [7].

Misbinding of features such as color and form also is reported with long presentation times (1 min) and full attention [8]. When an equiluminant magenta-gray vertical grating is presented to one eye and an equiluminant green-gray horizontal grating to other eye, observers often report perceiving a magenta-green grating in either a horizontal or vertical orientation. The gray stripes within the dominant form, whether it is vertical or horizontal, are filled with color from the other eye’s suppressed form. This shows that a color can be bound to another form in a nonretinotopic location, and that color can maintain its neural representation even when the form to which the color belongs is suppressed.

The studies described above concern the binding problem in the spatial domain. What about binding in the temporal domain? Neural processing of visual stimuli can involve different neural delays at each stage of the visual system [9–14]. In general, these neural delays are short -- on the order of 100msec or less [13,15,16] -- so for a static stimulus the delays can be unimportant. The delays, however, can be critical for a stimulus that changes over time. Studies of perceptual asynchrony of motion and color brought attention to the temporal binding problem. For example, when a stimulus alternates in both color (e.g., red or green) and direction of motion (e.g., up or down), observers perceive the new color of the stimulus before the new motion. In this case, the color is perceived to be bound to the preceding direction of motion rather than the simultaneously presented direction [17–21]. This mismatch between the color and motion of the physical stimulus and the color and motion perceived is called perceptual asynchrony. Other studies find perceptual asynchrony for color and location [22] or color and orientation [18,23].

This kind of mismatch between a physical stimulus and a percept also is found between a pulsed stimulus and a continuously changing stimulus. When a bar moves horizontally from left to right, and in the middle of its trajectory another bar is pulsed above the moving bar, the pulsed bar is perceived to be behind the moving bar even though they are physically aligned. Because the pulsed (“flashed”) stimulus is perceived to lag behind the moving stimulus, this phenomenon is called the flash-lag effect [24, 25].

A simple explanation for the flash-lag effect is that a moving stimulus is more rapidly processed neurally compared to a pulsed stimulus [26, 27]. This differential latency hypothesis assumes that differences in neural latencies between the two stimuli are directly related to differences in perceptual latencies. Neural latencies depend on luminance [15, 28,29]; the latency is shorter for a higher luminance stimulus compared to a lower luminance stimulus. Thus, if the pulsed stimulus has higher luminance than the continuously changing stimulus, then the pulsed stimulus could lead instead of lag behind. Indeed, experiments show that flash-lead can occur instead of flash-lag [26, 30]. However, when the onset of a pulsed and a moving stimulus are at the same time, the visual system has no information to determine which stimulus is pulsed and which is moving. Thus, according to this hypothesis, in this condition there should be no flash-lag effect, which is contrary to experimental findings [31]. Further, in this condition, a high-luminance pulsed stimulus does not elicit flash-lead [30]. This suggests that the differential latency hypothesis is not sufficient to explain the flash-lag effect.

Others have proposed that the flash-lag effect is due to extrapolation of the trajectory of the moving stimulus, as a mechanism to compensate neural delays [25, 31]. The extrapolation hypothesis assumes that the visual system can veridically represent the object in time by correcting for initial sensory neural processing. According to the extrapolation hypothesis, a continuously changing stimulus should overshoot the reversal point when a continuously changing stimulus abruptly stops or changes its directions. However, this does not occur [27, 32–34].

Because a sudden change in the continuous stimulus after pulse onset affects the flash-lag effect, a temporal integration hypothesis has been proposed. It posits that the visual system averages sensory signals over a certain time window [32, 33].

Although the mechanism of the flash-lag effect is not fully resolved [35], it remains a useful tool to examine a continuously changing stimulus, using a pulsed stimulus as a probe. Unlike the stimuli used in perceptual asynchrony experiments described above, the flash-lag paradigm uses features that change along a perceptual continuum.

The flash-lag effect is found not only with motion but also with other features, such as continuously changing color, luminance, or spatial frequency [36]. In the motion flash-lag effect, a moving stimulus changes its location over time whereas in the flash-lag of other features the location of a continuously changing stimulus is fixed and the change is in only the feature itself. For example, when a disc is pulsed during the presentation of another disc that is continuously changing in color, and both discs are identical in color at the moment when they both are present, the color of the continuously changing disc is perceived farther along the color continuum than the pulsed disc. Thus, physically identical discs are perceived to be different. For luminance and spatial frequency, as well, the continuously changing stimulus is perceived to be shifted ahead of the pulsed stimulus on the feature continuum. Importantly, the magnitude of the perceptual shift in terms of time along the continuously changing continuum varies for different features. The average perceptual-shift time along the continua of color, luminance, or spatial frequency is about 400 msec, 40 msec, or 80 msec, respectively [36]. Note that the perceptual–shift time for color is 5–10 times longer than for the other two features. The large difference in the magnitudes of perceptual-shift time for different features raises a basic question. How is our percept affected by a combination of features that have different perceptual-shift times?

The experiments here tested whether feature binding integrates two different features while maintaining their own independent temporal shifts, or instead integrates simultaneously presented features so all of the features of a single object have the same temporal shift. If features keep their original delays prior to feature binding, this would be consistent with independent processing of features that are subsequently integrated. On the other hand, if feature binding occurs before neural processes mediating the temporal shifts, then feature integration may equalize the flash-lag effect for both features. These alternatives were evaluated by determining the percept of each feature of a continuously changing stimulus.

METHOD

Observers

Three observers participated in the study. Each had normal color vision as determined using a Neitz anomaloscope, and had normal color discrimination on the Farnsworth-Munsell 100-Hue test. Heterochromatic flicker photometory (HFP) at 5cd/m2 was used to determine equiluminance for each observer. The HFP field size was 1.6 deg and the temporal frequency was 12.5 Hz. Author P.K. (observer #1) had knowledge about the experiments. Observers #2 and #3 did not know the design or purpose of the study. Consent forms were completed in accordance with the policies of the University of Chicago’s Institutional Review Board.

Apparatus

Stimuli were generated using an iMac computer and presented on a calibrated NEC color display (Accusync 120). The cathode ray tube (CRT) had 1280 × 1024 pixel resolution and a refresh rate of 75 Hz noninterlaced. A game pad was used to collect responses from observers.

Stimuli

A schematic drawing of the stimulus is shown in Figure 1 during a 1440 msec presentation. (color version online). Both the continuously changing stimulus and the pulsed stimulus were a bar (2.6×0.4 deg, 11 cd/m2). For the continuously changing stimulus, the chromaticity changed within a fixed range of L/(L+M) of 0.108, chosen randomly from an overall range of L/(L+M) from 0.62 to 0.80; S/(L+M) was fixed at 0.20. At the same time the color changed, the bar rotated through 170 degrees at about 20 r.p.m. A central fixation cross (0.36 × 0.36 deg, 0.05 deg thick, 40 cd/m2) was metameric to equal-energy-spectrum (EES) ‘white’ [L/(L+M)=0.665, S/(L+M)=1.0]. The unit of S/(L+M) is arbitrary and set here to 1.0 for EES.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the experimental stimuli (color version online). The same experimental stimuli were used for all three conditions: (i) Separate Color condition (color matching only), (ii) Separate Orientation condition (orientation matching only) and (iii) the Both condition (both color and orientation matching simultaneously).

Procedure

Prior to making measurements, each observer dark-adapted for five minutes in order to bring the eyes of the observer to the same state of adaptation each day. Before beginning an experiment, observers adjusted a chin rest so it was centered on the screen. The chin rest minimized head movement.

When observers started the experiment by pressing a pre-assigned button, a fixation cross appeared for 5 seconds. Then, the continuously changing stimulus was presented either on the left or right side of the fixation cross (randomly selected). The chromaticity of the bar changed continuously within its fixed range from either higher L/(L+M) to lower L/(L+M), or from lower L/(L+M) to higher L/(L+M). Simultaneously, the bar rotated in either the clockwise or counter-clockwise direction. Exactly halfway through the presentation, a second stimulus was briefly pulsed (80ms) on the other side of the fixation point (Fig. 1). Initially, the chromaticity and orientation of the pulsed stimulus were the same as the continuously changing stimulus at the instant both were presented. On each presentation, the observer compared the pulsed stimulus to the continuous stimulus (1) in only color (Separate Color condition), (2) in only orientation (Separate Orientation condition) or (3) in both color and orientation (Both condition). For example, in the “Both” condition, the observer responded with pre-assigned buttons to indicate whether the color [orientation] of the pulsed stimulus appeared redder [more leftward] or greener [more rightward] than the continuously changing stimulus. After making a response, the observer pressed a button to start the next trial. On the next presentation, the chromaticity and orientation of the pulsed stimulus were changed from the previous presentation. If the observer indicated, for example, that the color of the pulsed stimulus was greener and the orientation was more rightward on the previous presentation, then the chromaticity and orientation of the pulsed stimulus were shifted to a higher L/(L+M) chromaticity and a more leftward orientation than in the previous trial. Trials were continued until the observer reported a match between the pulsed and continuous stimuli. For the Both condition, the observer was instructed to give the match response only when both the color and orientation of the pulsed stimulus simultaneously matched the continuously changing stimulus.

Each trial began with a different color range, chosen from within the overall color range mentioned above, and a different starting orientation. Also the direction of chromaticity change (from higher L/(L+M) to lower L/(L+M), or the opposite direction) and the direction of rotation (clockwise or counter-clockwise) were randomized on each trial. The randomization minimized possible adaptation and also prevented the observer from memorizing the color and/or orientation of the middle frame from the initial or later pulsed-stimulus presentations.

RESULTS

Figure 2 shows results from the experiment for three observers. Measurements for Separate Color and Separate Orientation were collected in 3 sessions (2×3=6 values); Both Color and Both Orientation values were from 4 sessions (2×4=8 values) for a total of 14 values for each observer. Each value was the mean of at least 9 replicated measurements within a single session.

Figure 2.

Results for the Separate conditions and the Both condition. The vertical axis represents the perceptual-shift time in msec and the horizontal axis indicates the three different conditions: (i) Separate Color, (ii) Separate Orientation, and (iii) Both. In the Separate conditions, the observer judged color or orientation separately in different runs, whereas in the Both condition the observer judged both color and orientation simultaneously on each trial. Striped bars [solid bars] represent the perceptual shift in orientation [color]. Error bars are standard errors of the mean from measurements collected in different sessions.

The vertical axis is the perceptual-shift time in msec along the continuously changing feature continuum, and the horizontal axis represents two different types of conditions: (i) the Separate conditions or (ii) the Both condition. In the Separate conditions, the observer matched color or orientation in separate runs whereas in the Both condition observers matched both color and orientation simultaneously on each trial. Striped bars show the perceptual-shift time for orientation and solid bars show the perceptual-shift time for color. Each observer in every condition had a larger perceptual-shift time for color than for orientation (solid bars are higher than striped bars). The difference in perceptual-shift time between color and orientation varied from 78 msec to 295 msec among observers. Figure 3 shows schematically how the difference in perceptual-shift times affected perception during the Both condition. Here the values are based on the average from the three observers (264 msec advance for color and 121 msec for orientation). The difference between the perceptual-shift time for color and orientation was significant for all observers (observer #1 F(1,10)=275.2, p<0.001; observer #2 F(1,10)=181.3, p<0.001; observer #3 F(1,10)=35.4, p<0.001). Furthermore, pairwise comparisons using the Tukey-Kramer procedure showed a significant difference between the perceptual-shift time for color versus orientation in all conditons and for every observer (observer #1, p<0.001; observer #2, p<0.001; observer #3, p<0.02). Perceptual-shift time did not differ significantly between the Separate and Both conditions for observers #1 and #3 but there was a difference for observer #2 (observer #1 F(1,10)=0.5, p>0.4; observer #2 F(1,10)=14.2, p<0.01; observer #3 F(1,10)=0.2, p>0.6). The interaction between features and condition-types (Separate or Both) was not statistically significant for observers #1 and #3 but was significant for observer #2 (observer #1 F(1,10)=0.06, p>0.8; observer #2 F(1,10)=31.0, p<0.001; observer #3 F(1,10)=0.2, p>0.6).

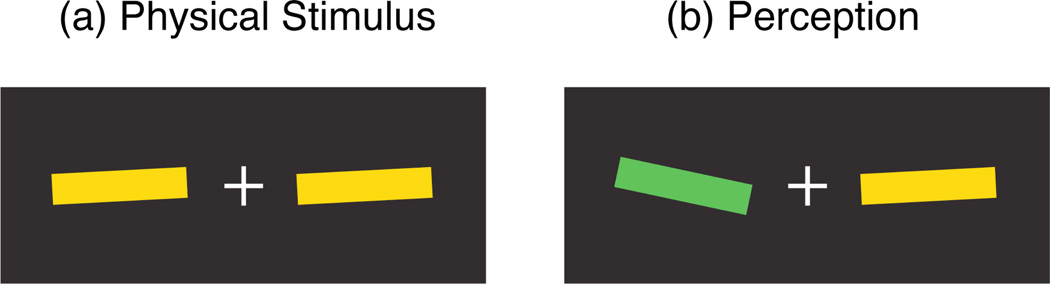

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration (color version online) showing how a continuously changing stimulus (left of fixation) is perceived when the pulsed stimulus (right of fixation) is presented. The continuously changing stimulus appears more advanced in color than orientation (based on average from 3 observers: 264 msec advance for color, 121 msec for orientation).

The main point is that even when observers matched both color and orientation simultaneously, the perceptual-shift time for color was significantly longer than for orientation. This implies that observers perceived the continuously changing stimulus to have a combination of orientation and color that was never actually presented to the eye.

DISCUSSION

When the color and orientation of an object both changed continuously, perceptual asynchrony of color and orientation was observed even when both were features of the same object and were judged simultaneously. This difference in the magnitude of the perceptual-shift time between color and orientation was found for every observer. This implies that each feature maintained a distinct perceptual-shift time, and thus indicates that feature binding occurs after independent temporal processing of features.

Although explicit feature binding itself was not required to complete the task here, observers perceived the continuously changing stimulus as a unified object. Note that the flash-lag effect can vary with the speed of the moving stimulus [25], so the absolute values of the perceptual shifts found here may depend on the rate of change of each continuously varying feature.

The main result may seem suprising because several studies suggest that features from the same object tend to be processed together [37]. With a briefly presented box with a single line drawn through it, observers are more accurate at reporting judgments about the same object (e.g., the size of the box and the side of its gap) than two different objects (e.g., the size of the box and the orientation of the line; [38]). This is termed the ‘same-object advantage’. This same-object advantage is reported also when observers are asked to detect a luminance decrement among the four ends of two bars, immediately after a cue. When an invalid cue is given to one end of a bar, the observer is faster to detect the luminance change in the other end of the same bar, compared to the luminance change in an equidistant end of the other bar [39].

The McCollough effect [40] suggests that color and orientation are coded in combination during visual processing. The McCollough effect is an orientation-contingent color aftereffect where adaptation, for example, to red vertical and green horizontal gratings later causes achromatic vertical and horizontal gratings to appear greenish and reddish, respectively. This suggests that color and orientation are represented jointly at some level of the visual system, but the time difference between color and orientation of a few hundred milliseconds, as found here, is too short to disrupt the McCollough-effect adapting procedure [40].

Early binding of features of the same object is suggested also by a study using color and orientation, either spatially superimposed or spatially separated [41]. In the spatially-superimposed condition, a red-gray right-tilted grating or a green-gray left-tilted grating is shown through a semicircular window above a fixation cross. In the spatially-separated condition, a red (or green) uniform semicircle is shown above the fixation cross, and an achromatic right (or left) tilted grating is shown in semicircular form below the fixation cross. In the spatially-superimposed condition, the highest alternation rate for threshold accuracy of the correct pairing of color with orientation is 18.8 Hz (~27msec half cycle), but in the spatially separated condition it is below 3 Hz (longer than 167 msec half cycle).

The most important difference between these studies and the present one is that here features were varied along a continuum, whereas in the previous studies features were abruptly alternated between two very different colors and orientations. One possibility is that when features change abruptly rather than continuously they may be more readily paired from the synchrony of temporal transients [42].

Separate coding of color and form in V1, as well as in higher visual areas, is a classic claim [3–5], though more recent work shows that this functional segregation may not be as discrete as previously thought [43]. In macaque visual cortex, there are cells that are orientation-selective as well as color-selective [44, 45]. Results from fMRI studies suggest that both segregated processing and conjunctions of color and form are found throughout human visual cortex [46, 47], though fMRI is too coarse spatially to reveal any single cell is selective for both features. Although there are visual areas that are selective for color and orientation, it is difficult to pinpoint which level of visual processing directly relates to perception of integrated features. Overall, there is no definitive conclusion concerning how neural coding of feature conjunctions contribute to perception.

In sum, the results here show that features maintain their own perceptual-shift time, indicating primarily separate temporal neural processing prior to perceptual feature binding. This also implies that the combination of color and orientation that one sees with two continuously changing features of an object is a combination never physically presented to the eye.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by a National Institutes of Health Grant EY-04802

REFERENCES

- 1.James W. A pluralistic universe: Hibbert lectures at Manchester college on the present situation in philosophy. New York: Longmans, Green & Co; 1909. pp. 207–208. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roskies AL. The Binding Problem. Neuron. 1999;24:7–9. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80817-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Livingstone MS, Hubel DH. Segregation of form, color, movement, and depth: anatomy, physiology, and perception. Science. 1988;240:740–749. doi: 10.1126/science.3283936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Felleman DJ, Van Essen DC. Distributed hierarchical processing in the primate cerebral cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 1991;1:1–47. doi: 10.1093/cercor/1.1.1-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeki S. A Vision of the Brain. Oxford UK: Blackwell; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Treisman A, Schmidt H. Illusory conjunctions in the perception of objects. Cognitive Psychol. 1982;14:107–141. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(82)90006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Treisman A, Gelade G. A feature-integration theory of attention. Cognitive Psychol. 1980;12:97–136. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(80)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong SW, Shevell SK. Color-binding errors during rivalrous suppression of form. Psychol. Sci. 2009;20:1084–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02408.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dreher B, Fukada Y, Rodieck RW. Identification, classification and anatomical segregation of cells with X-like and Y-like properties in the lateral geniculate nucleus of old-world ptimates. J. Physiol. 1976;258:433–452. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schiller PH, Malpeli JG. Functional specificity of lateral geniculate nucleus laminae of the rhesus monkey. J. Neurophysiol. 1978;41:788–797. doi: 10.1152/jn.1978.41.3.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan E, Shapley RM. X and Y cells in the lateral geniculate nucleus of macaque monkeys. J. Physiol. 1982;330:125–143. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura K, Matsumoto K, Mikami A, Kubota K. Visual response properties of single neurons in the temporal pole of behaving monkeys. J. Neurophysiol. 1994;71:1206–1221. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.3.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmolesky MT, Wang Y, Hanes DP, Thompson KG, Leutger S, Schall JD, Leventhal AG. Signal timing across the macaque visual system. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;79:3272–3278. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.6.3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lamme VA, Roelfsema PR. The distinct modes of vision offered by feedforward and recurrent processing. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:571–579. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01657-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lennie P. The physiological basis of variations in visual latency. Vision Res. 1981;21:815–824. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(81)90180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maunsell JHR, Gibson JR. Visual response latencies in striate cortex of the macaque monkey. J. Neurophysiol. 1992;68:1332–1344. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.4.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moutoussis K, Zeki S. A direct demonstration of perceptual asynchrony in vision. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1997a;264:393–399. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1997.0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moutoussis K, Zeki S. Functional segregation and temporal hierarchy of the visual perceptive systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1997b;99:9527–9532. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1997.0196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeki S, Moutoussis K. Temporal hierarchy of the visual perceptive systems in the Mondrian world. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1997;264:1415–1419. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1997.0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbur JL, Wolf J, Lennie P. Visual processing levels revealed by response latencies to changes in different visual attributes. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1998;265:2321–2325. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arnold DH, Clifford CW, Wenderoth P. Asynchronous processing in vision: color leads motion. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:596–600. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pisella L, Arzi M, Rossetti Y. The timing of color and location processing in the motor context. Exp. Brain Res. 1998;121:270–276. doi: 10.1007/s002210050460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clifford CWG, Arnold DH, Pearson J. A paradox of temporal perception revealed by a stimulus oscillating in colour and orientation. Vision Res. 2003;43:2245–2253. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(03)00120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacKay DM. Perceptual stability of a stroboscopically lit visual field containing self-luminous objects. Nature. 1958;181:507–508. doi: 10.1038/181507a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nijhawan R. Motion extrapolation in catching. Nature. 1994;370:256–257. doi: 10.1038/370256b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Purushothaman G, Patel SS, Bedell HE, Ogmen H. Moving ahead through differential visual latency. Nature. 1998;396:424. doi: 10.1038/24766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitney D, Murakami I. Latency difference, not spatial extapolation. Nat. Neurosci. 1998;1:656–657. doi: 10.1038/3659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gawne TJ, Kjaer TW, Richmond BJ. Latency: another potential code for feature binding in striate cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 1996;76:1356–1360. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.2.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maunsell JHR, Ghose GM, Assad JA, McAdams CJ, Boudreau CE, Noerager BD. Visual response latencies of magnocellular and parvocellular LGN neurons in macaque monkeys. Visual Neurosci. 1999;16:1–14. doi: 10.1017/s0952523899156177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel SS, Ogmen H, Bedell HE, Sampath V. Flash-lag effect: differential latency, not postdiction. Science. 2000;290:1051. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5494.1051a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khurana B, Nijhawan R. Extrapolation or attention shift: Reply to Baldo and Klein. Nature. 1995;378:566. doi: 10.1038/378565a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brenner E, Smeets JBJ. Motion extrapolation is not responsible for the flash-lag effect. Vision Res. 2000;40:1645–1648. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(00)00067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eagleman DM, Sejnowski TJ. Motion integration and postdiction in visual awareness. Science. 2000;287:2036–2038. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitney D, Murakami I, Cavanagh P. Illusory spatial offset of a flash relative to a moving stimulus is caused by differential latencies for moving and flashed stimuli. Vision Res. 2000;40:137–149. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(99)00166-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nijhawan R. Visual prediction: psychophysics and neurophysiology of compensation for time delays. Behav. Brain Sci. 2008;31:179–239. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X08003804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheth B, Nijhawan R, Shimojo S. Changing objects lead briefly pulsed ones. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3:489–495. doi: 10.1038/74865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scholl BJ. Objects and attention: the state of the art. Cognition. 2001;80:1–46. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(00)00152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duncan J. Selective attention and the organization of visual information. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1984;113:501–517. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.113.4.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Egly R, Driver J, Rafal R. Shifting visual attention between objects and locations: evidence for normal and parietal lesion subjects. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1994;123:161–177. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.123.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCollough C. Color adaptation of edge-detectors in the human visual system. Science. 1965;149:1115–1116. doi: 10.1126/science.149.3688.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holcombe AO, Cavanagh P. Early binding of feature pairs for visual perception. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4:127–128. doi: 10.1038/83945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holcombe AO, Cavanagh P. Independent, synchronous access to color and motion features. Cognition. 2008;107:552–580. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sincich LC, Horton JC. The circuitry of V1 and V2: integration of color, form, and motion. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2005;28:303–326. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshioka T, Dow BM. Color, orientation and cytochrome oxidase reactivity in areas V1, V2 and V4 of macaque monkey visual cortex. Behav. Brain Res. 1996;76:71–88. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(95)00184-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson EN, Hawken MJ, Shapley R. The orientation selectivity of color-responsive neurons in macaque V1. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:8096–8106. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1404-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Engel SA. Adaptation of oriented and unoriented color-selective neurons in human visual areas. Neuron. 2005;45:613–623. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seymour K, Clifford CW, Logothetis NK, Bartels A. Coding and binding of color and form in visual cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 2010;20:1946–1954. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]