Abstract

Human herpesvirus 6A (HHV-6A) and human herpesvirus 6B (HHV-6B) are associated with a variety of conditions including rash, fever, and encephalitis and may play a role in several neurological diseases. Here luciferase immunoprecipitation systems (LIPS) was used to develop HHV-6 serologic diagnostic tests using antigens encoded by the U11 gene from HHV-6A (p100) and HHV-6B (p101). Analysis of the antibody responses against Renilla luciferase fusions with different HHV-6B p101 fragments identified an antigenic fragment (amino acids 389 to 858) that demonstrated ~86% seropositivity in serum samples from healthy US blood donors. Additional experiments detected a HHV-6A antigenic fragment (amino acids 751-870) that showed ~48% antibody seropositivity in samples from Mali, Africa, a known HHV-6A endemic region. In contrast to the high levels of HHV-6A immunoreactivity seen in the African samples, testing of US blood donors with the HHV-6A p100 antigenic fragment revealed little immunoreactivity. To potentially explore the role of HHV-6 infection in human disease, a blinded cohort of controls (n=59) and chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) patients (n=72) from the US was examined for serum antibodies. While only a few of the controls and CFS patients showed high level immunoreactivity with HHV-6A, a majority of both the controls and CFS patients showed significant immunoreactivity with HHV-6B. However, no statistically significant differences in antibody levels or frequency of HHV-6A or HHV-6B infection were detected between the controls and CFS patients. These findings highlight the utility of LIPS for exploring the seroepidemiology of HHV-6A and HHV-6B infection, but suggest that these viruses are unlikely to play a role in the pathogenesis of CFS.

Keywords: Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS), Human Herpes Virus-6 (HHV6), luciferase immunoprecipitation systems (LIPS)

Introduction

Human Herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) is a member of the β-herpesvirus subfamily of Herpesviridae and contains a genome of approximately 160 kb encoding 97 unique genes [1]. Two variants have been identified, HHV-6A and HHV-6B, with approximately 90% nucleotide homology. While molecular genotyping has shown that infection with the HHV-6B variant is predominantly (>95%) found in Japan [2], Europe [3,4] and the US [5], infection with the HHV-6A variant is the major endemic form in West Africa [6].

Infection with HHV-6 usually presents as a febrile illness in children within the first 3 years of life [1]. During initial HHV-6 infection in children, approximately 20% display roseola infantum, which is an illness characterized by high fever and extensive rash on the face and body [7]. Although 100% of adults are proposed to be HHV-6 infected, this virus has also been associated with several neurological conditions [8]. For example, HHV-6 infection is linked to encephalitis in children and immunosuppressed adults [1] and is the likely culprit of many unexplained cases of encephalitis [9-11]. Evidence for a pathological role of HHV-6 infection in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy has also been demonstrated as HHV-6 DNA has been detected in affected brain tissue [12,13]. Although controversial, HHV-6 may also be involved in chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) and multiple sclerosis [8]. HHV-6 DNA has been found in brain lesions of multiple sclerosis patients [14,15] and serological studies have reported elevated antibodies against HHV-6 in early stages of multiple sclerosis [16,17]. In CFS, one study found that 70% of the patients versus 20% of the controls showed active HHV-6 replication [18]. However, two other studies found no significant association between HHV-6 infection and CFS [19,20].

Given the potential role of HHV-6 infection in different diseases, better and more accurate methods are needed to diagnose and monitor infection. Quantitative PCR-based tests are useful for HHV-6 diagnosis and determining viral load, but serological tests such as immunofluorescence, Western blots, and ELISAs have the potential to differentiate latent from lytic infection, as well as, have the ability to detect past exposure. Unfortunately, many of the current HHV-6 ELISAs employ crude viral cell lysates which may show cross-immunoreactivity with other herpes virus proteins and are unable to distinguish between HHV-6A and HHV-6B infection. However, based on the identification of the HHV-6 U11 gene product as a diagnostic antigen [21,22], more recent Western blotting studies have used the U11 recombinant protein, including the p101 protein of HHV-6B, to detect seropositivity in approximately 82% of healthy Japanese adults [23]. Nevertheless, the approach of using HHV-6 Western blotting is not highly quantitative and is less than optimal for high-throughput seroepidemiologic studies.

Previously, the liquid phase luciferase immunoprecipitation systems (LIPS) that employs mammalian cell-produced, recombinant Renilla luciferase fusion antigens was used for the quantitative evaluation of antibody responses to a number of different herpes viruses including HSV-1 [24], HSV-2 [24], CMV [25], EBV [26,27], HHV-8 [28,29], rhesus lymphocryptovirus [30] and rhesus CMV [31]. Here novel LIPS assays for measuring antibody responses against recombinant antigens from HHV-6A and HHV-6B were developed and used to study the role of HHV-6 infection in CFS.

Material and methods

Subject samples

Informed written consent was obtained from all subjects in accordance with the human experimentation guidelines of the Department of Health and Human Services and the studies were conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. Sera were obtained from volunteers or patients under institutional review board-approved protocols at the NIH, Bethesda, MD and Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC. One cohort contained serum samples (n=22) from adult blood donors from the NIH Clinical Center, NIH. Additionally, a cohort of serum samples (n=22) from Mali, Africa was studied. A third cohort, collected from Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC contained both control subjects (n=59) and CFS patients (n=72), represented random samples selected from a previously published study [32]. All CFS patients fulfilled the established clinical criteria [33]. The average age of the control subjects and CFS patients was approximately 48 and 50 years, respectively. The control and CFS serum samples were analyzed for anti-HHV-6 antibodies as anonymous, de-identified blinded samples.

Generation of protein fragments for HHV-6A and HHV-6B serological testing

The mammalian Renilla luciferase expression vector, pREN2, was used to generate all plasmids. HHV-6 protein fragments were amplified by PCR with gene specific primers using genomic DNA (Advanced Biotechnologies Inc., MD). For the p101 protein of HHV-6B, six different protein fragments were generated including p101-Δ1 (aa 2-389), p101-Δ2 (aa 389-858), p101-Δ3 (aa 389-567), p101-Δ4 (aa 567-738) and p101-Δ5 (aa 738-858). In addition, four different protein fragments were generated for the p100 protein of HHV-6A including p100-Δ2 (aa 390-870), p100-Δ3 (aa 390-579), p100-Δ4 (aa 580-750), and p100-Δ5 (aa 751-870). All HHV-6 DNA fragments were subcloned downstream of Renilla luciferase and a stop codon was inserted directly after the HHV-6 protein coding sequence. Each plasmid construct was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The details of the nucleotide and amino acid sequences for the two most informative constructs used for serological testing in our study, HHV-6A-Δ5 and HHV-6B-Δ2 have been deposited in the Gen-Bank database with the accession numbers JX152762 and JX235339, respectively.

Production of Renilla luciferase-antigen fusion proteins

Fusion proteins for the different HHV-6 protein fragments were generated by transfecting Cos-1 cells with pREN2 expression vectors using X-tremeGene (Roche). Forty-eight hours later, cell lysates were prepared from the Cos1 cells by first briefly washing the cell layer with PBS. Next, lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100 and 50% glycerol containing protease inhibitors) was added and the cell layer was scraped and sonicated on ice. The lysates were centrifuged twice at 13,000 x g, supernatants collected and then stored at -20°C until use. The activities of the lysates (light units, LU/ ml) were next determined using a single tube luminometer (20/20 from Turner Scientific) with a coelenterazine substrate mix (Promega, Madison, WI).

LIPS analysis

Using a 96-well plate format, all LIPS assays were performed at room temperature as previously described [34]. Patient sera were first diluted 1:10 in assay buffer A (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100) in 96-well polypropylene microtiter plates. To quantify antibody titers by LIPS, 40 μl of buffer A, 10 μl of diluted human plasma (1 μl equivalent), and 50 μl of 1 × 107 light units (LU) of Renilla luciferase-antigen Cos1 cell extract, diluted in buffer A, were added to each well of polypropylene plates and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Next, 7 μl of a 30% suspension of Ultralink protein A/G beads (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) in PBS was added to the bottom of each well of a 96-well filter HTS plate (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The 100 μl antigen-antibody reaction mixture was then transferred to filter plates and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature on a rotary shaker. Proteins bound to the protein A/G beads were washed 10 times with buffer A and twice with PBS using a BioMek FX work station (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) with an integrated vacuum manifold. After the final wash, LU were measured in a Berthold LB 960 Centro microplate luminometer (Berthold Technologies, Bad Wilbad, Germany) using coelenterazine substrate mix (Promega, Madison, WI). All of the LU data shown represent the average of at least two independent experiments.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA) was used for data and statistical analyses. For the calculation of sensitivity and specificity, a simple statistically based cut-off value for each antigen was derived from the mean value plus 10 standard deviations of the buffer blanks. As described in the figure legends, heatmap was used in Figures 1 and 2 to signify the relative antibody levels in the samples. Results for quantitative HHV-6A and HHV-6B antibody levels between the controls and CFS patients were reported as the geometric mean ± the 95% confidence interval. Mann-Whitney U tests were used for comparison of antibody titers in different groups and the level of significance was set at P<0.05. The statistical significance of prevalence differences in HHV-6 infection were also evaluated using the Fischer’s exact test.

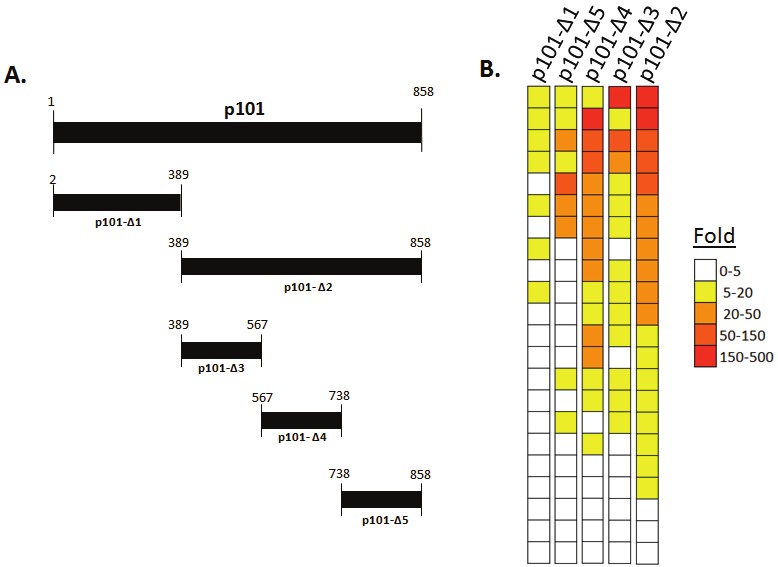

Figure 1.

Detection of anti-p101 HHV-6 antibody responses in healthy US blood donors. (A) Diagrammatic representation of the five different protein fragments from the p101 protein of HHV-6B tested by LIPS (B) Heat map representation of antibody responses to the five different p101 HHV-6B protein fragments in 22 healthy US blood donors. Antibody levels were transformed to fold above buffer blank and then color coded as indicated by the scale. Each individual row represents the antibody level in a single serum sample tested with the different fragments.

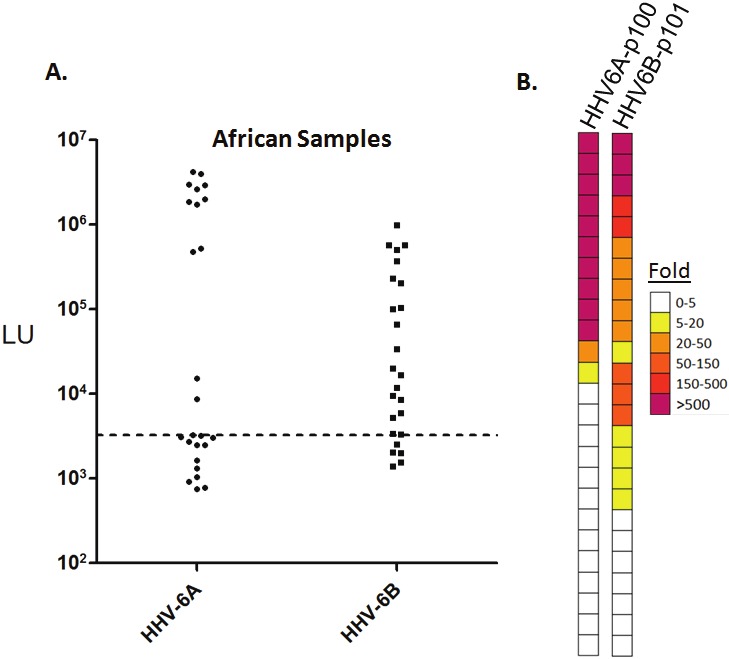

Figure 2.

HHV-6A and HHV-6B antibody titers in African samples. (A) Scatter plot representation of antibody titers detected by LIPS against the most immunoreactive HHV-6A protein fragment, p100-Δ5, and the HHV-6B p101 protein in African samples. Each circle or square symbol represents average of at least two independent experiments in each individual sample. The dashed line represents the mean plus 10 standard deviations of buffer blanks as cut-off point. (B) Heat map representation of antibody responses of African samples to HHV-6A p100-Δ5 and HHV-6B p100-Δ2. Antibody levels were transformed to fold over buffer blank then color coded as indicated by the scale at right.

Results

Identification of an immunodominant p101 protein fragment of HHV-6B

Our previously published LIPS study detecting antibodies against protein fragments of the U11 tegument protein of CMV showed high diagnostic performance [25]. We hypothesized that protein fragments of the corresponding functional homolog, p101 of HHV-6B, might also be informative for serological testing. Using HHV-6B genomic DNA as a template, initially two different fragments spanning the full-length p101 protein were generated as C-terminal Renilla luciferase fusion proteins (Figure 1A). These two HHV-6B p101 constructs were expressed in Cos1 cells and the lysates were tested in LIPS assays to evaluate serum samples from 22 healthy US blood donors. The serological discriminatory potential against each of the fragments was evaluated by comparing the fold signal over buffer blanks in a heatmap format. Values greater than 5-fold were assigned a seropositive status. Using the p101-Δ1 N-terminal fragment, seven of the 22 sera showed seropositivity above the cut-off value (Figure 1B). In contrast, the p101-Δ2 protein C-terminal half of p101 was more useful and detected positive antibody responses in 84% (19/22) of the healthy blood donors (Figure 1B). The dynamic range of the antibody titers against the p101-Δ2 protein fragments in the serum samples varied by approximately 100-fold ranging from 1,119 to 135,200 LU. Based on the highly immunoreactive nature of p101-Δ2 protein fragment in 86% of the normal blood donors, three additional non-overlapping subfragments of this region were generated and tested to explore whether they might be more diagnostically useful (Figure 1A). However, all three subfragments were less immunoreactive than the p101-Δ2 protein fragment (Figure 1B). Specifically, the p101-Δ3 fragment displayed immunoreactivity with 14 of the 22 serum samples, p101-Δ4 was immunoreactive with 16 of the 22 and the p101-Δ5 reacted with 9 of the 22 healthy blood donor samples. Further analysis revealed that the p101-Δ4 and p101-Δ2 correlated well, but the other protein fragments were less immunogenic. Collectively, these results with HHV-6-Δ2 fragment, the most useful serologically, suggest that antibodies against HHV-6B antibodies are relatively common in US human adults.

Detection of antibodies directed against p101 of HHV-6A in African serum samples

Due to the high prevalence of HHV-6A infection in certain geographical areas such as West Africa, immunoreactivity was also tested against the p100 protein of HHV-6A. Screening of four p100 HHV-6A protein fragments with a cohort of serum samples from Mali Africa revealed that one antigenic fragment derived from the C-terminus of p100 (designated p100-Δ5; amino acids 751-870) was the most immunoreactive (Figure 2A and data not shown). Analysis of the scatter plot revealed that 12 of the 25 samples showed antibody responses above the cut-off for the HHV-6A p101 fragment. Interestingly the HHV-6A seropositive samples in this cohort showed a bimodial antibody response. Six of the serum samples showed extremely high antibody levels over 800,000 LU, while the other 13 samples showed much lower levels of antibody ranging from 4,000 to 40,000 LU (Figure 2A). Retesting the African samples for anti-HHV-6B antibodies with the p100-Δ2 fragment revealed that 20 of the 25 samples were seropositive, in which several of the samples were HHV-6B seropositive but not HHV-6A seropositive (Figure 2A and Figure 2B). Additionally, direct comparisons of the anti-HHV-6A and HHV-6B antibody responses revealed that many of the very high titer African subjects with anti-HHV-6A antibodies all showed markedly lower reactivity against the HHV-6B p101 protein fragment. These findings suggest that many of African samples are infected with HHV-6A but do not formally exclude the possibility that several of the samples are also coinfected with the HHV-6B.

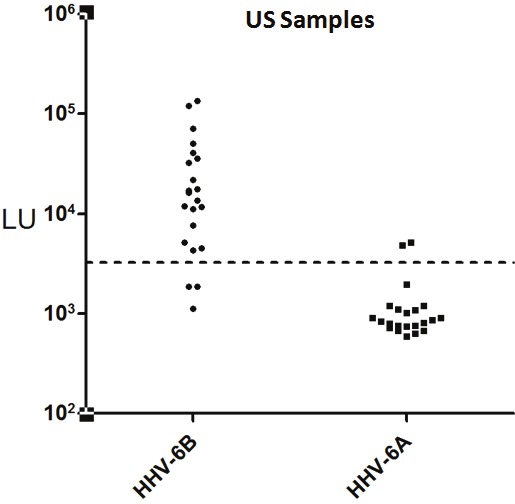

Due to the observed immunoreactivity of the African samples with HHV-6A antigenic target, HHV-6A immunoreactivity was also examined with the US blood donor samples. However, little immunoreactivity was detected with the p101 HHV-6A fragment in the US samples (Figure 3). In contrast to the immunoreactivity observed against the HHV-6B p101 antigen with the US samples, only a few, weak antibody responses were found in several of the high-HHV-6B seropositive subjects, which might represent cross-immunoreactivity between the p100 and p101 proteins. Taken together these results suggest that the Africa and the US clinical samples demonstrate markedly different variant-specific imimmunoreactivity which is consistent with epidemiological studies showing predominant HHV-6A and HHV-6B DNA in samples from Africa and the US, respectively.

Figure 3.

LIPS immunoreactivity detection against the HHV-6B p100 and HHV-6A p100 in US samples. Each circle or square symbol represents antibody levels in individual US samples. The dashed line represents the cut-off level for determining seropositivity. As shown, little immunoreactivity was detected by LIPS with the p101 HHV-6A.

HHV-6 immunoreactivity in CFS patients

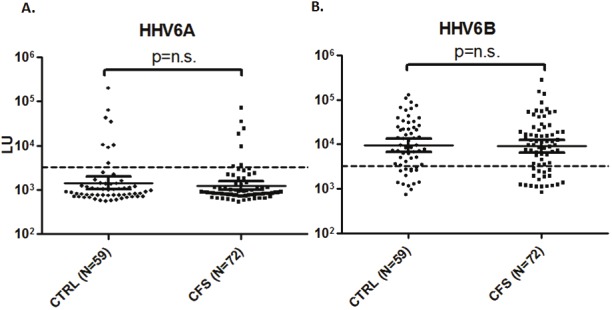

Based on the previously reported role HHV-6 virus activation and/or reactivation plays in chronic fatigue syndrome [18], a blinded cohort of 131 serum samples CFS patients and control subjects were evaluated for immunoreactivity against HHV-6A and HHV-6B. Following testing and unblinding, the cohort was found to consist of 59 control blood donors (n=59) and 72 patients with CFS. As shown in Figure 4A, the HHV-6A seroprevalence rates and relative titers were not significantly different between the two groups. Using the designated cutoffs, seropositive HHV-6A antibody responses were found in 8 of 59 (13.5%) of the samples in the control group and 7 of 72 (9.7%) in the CFS group. Among the seropositive individuals, the geometric mean level of antibodies in the healthy controls and CFS were 22,767 LU (95% CI; 7,823-66,258) and 14,478 LU (95% CI; 5,044-41,551), respectively, in which no statistically significant difference in antibody levels by the Mann Whitney U test was found between the two groups. Similar analysis for HHV-6B immunoreactivity revealed that 45 of 59 (76%) of the samples in the control group and 54 of 72 (75%) in the CFS group were seropositive with no statistical difference in prevalence between them observed by the Fischer’s exact test (Figure 4B). Moreover, the geometric level of HHV-6B antibodies in the control group was 22,767 LU (95% CI; 7,823-66,258) and 14,478 LU (95% CI; 5,044-41,551) in the CFS group. Taken together these results suggest that there is no evidence for increased infection with or serum antibodies directed against HHV-6A or HHV-6B in CFS.

Figure 4.

LIPS detection of antibodies to HHV-6A p100 (A) and HHV-6B p101 (B) in blood donor control subjects (n=59) and patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (n=72). Each circle or square symbol represents individual sample. The dashed line represents the cut-off level for determining seropositivity.

Discussion

Here we have used fragments of the p101 and p100 proteins of HHV-6B and HHV-6A, respectively, to develop serological tests for antibodies against these viruses. As might be expected, profiling antibody responses against multiple different HHV-6B fragments of p101 often showed overlapping immunoreactivity with the same patients. However, one of the largest p101 fragments of 320 amino acids in length showed the highest sensitivity with 86% seropositivity in the US samples and roughly matched the relative seropositivity (84%) seen by recombinant Western blotting in Japan, another HHV-6B endemic region [23]. Similarly, analysis of p100 protein of HHV-6A identified a 120 amino acid fragment that showed 48% seropositivity with the African samples. While our statistical approach of using a seropositive cut-off derived from the buffer blank (mean plus 10 standard deviations) is just an estimate, this value may underestimate the number of true seropositive samples. More detailed molecular and serological testing in parallel is needed to further define the cut-off value and explore whether there are some individuals who are seronegative for HHV-6 infection. It may be possible that the common assumption that 100% of adults are infected with HHV-6 is also incorrect. Other common herpes viruses including EBV, HSV-1 and CMV show infection prevalence’s of 95%, 50% and 45% respectively in the general population, suggesting the possibility that the true prevalence of HHV-6 infection is likely much lower than 100%.

The p101 fragment of HHV-6B used in our study for serologic testing shared 81% amino acid identity with the corresponding HHV-6A p100 fragment. The finding of predominantly HHV-6B p101 antibodies in the US with little immunoreactivity with p100 HHV-6A is consistent with detecting potential HHV-6B variant-specific immunoreactivity that may represent bot linear and conformational epitopes. Although testing of the African samples detected high levels of antibodies to both HHV-6A and HHV-6B, the reactivities seen in some of the high HHV-6A seropositive individuals were generally 4-100-fold higher than the levels of antibodies detected against p101 of HHV-6B. It is also possible that infection with the HHV-6A variant in the African samples induces more potent humoral responses than does the HHV-6B variant. While a high level of cross-reactivity was seen in our study between the p100 HHV-6A and p101 HHV-6B in the African samples, previous European and Japanese studies never tested samples from an HHV-6A endemic region [23,35]. Moreover, while both of these previous studies examined HHV-6B and HHV-6A DNA co-positive samples, the likely order of infection with each of the HHV-6 variants was unknown. Based on the marked high prevalence of HHV-6B in Japan, Europe and in the US, it is likely that HHV-6B infection often occurs before HHV-6A. Thus, it is possible that the antibody responses against the HHV-6A p100 protein are attenuated due to a phenomenon described as “original antigenic sin” [36]. In this scenario in the US, initial infection with HHV-6B and then subsequent infection by HHV-6A might result in lower titers of antibodies against the related HHV-6A p100 protein. Future studies with clinical samples DNA typed for HHV-6A and HHV-6B infection are needed to further explore antibody responses in coinfected individuals.

Studies with a cohort of control subjects and CFS samples also yielded some important information. First, HHV-6B immunoreactivity was independently confirmed to be the predominant detectable variant in a cohort of controls and CFS subjects collected from the US. However, no difference in HHV-6A or HHV-6B infection prevalence or antibody levels was found between the control subjects and CFS patients. The lack of statistically significant differences in antibody levels against HHV-6A and HHV-6B in CFS suggests that HHV-6 is unlikely to be involved in pathogenesis, a result that is consistent with two other studies that used different approaches to determine infection [19,20].

In conclusion, the results presented here demonstrate that LIPS produces highly robust values for studying HHV-6 serology. Unlike Western blotting there is no subjective scoring in the LIPS assay. Moreover, the defined antigens are easily applicable to high-throughput assay making large scale HHV-6 epidemiological studies feasible. We anticipate that the application of these LIPS test will be useful for studying the role of HHV-6 infection in other diseases including following transplantation and other neurological diseases.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and from the Center for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine. Additional funding for the CFS subproject was from U.S. Public Health Service Award R01 ES015382 from the National Institute of Environmental and Health Science; and the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program (CDMRP) Award W81XWH-07-1-0618.

Abbreviations

- CFS

Chronic fatigue syndrome

- HHV-6

Human herpesvirus 6

- LIPS

Luciferase Immunoprecipitation Systems

- LU

light units

- SD

standard deviations

References

- 1.Braun DK, Dominguez G, Pellett PE. Human herpesvirus 6. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:521–567. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.3.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka-Taya K, Kondo T, Mukai T, Miyoshi H, Yamamoto Y, Okada S, Yamanishi K. Seroepidemiological study of human herpesvirus-6 and -7 in children of different ages and detection of these two viruses in throat swabs by polymerase chain reaction. J Med Virol. 1996;48:88–94. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199601)48:1<88::AID-JMV14>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aberle SW, Mandl CW, Kunz C, Popow-Kraupp T. Presence of human herpesvirus 6 variants A and B in saliva and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of healthy adults. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:3223–3225. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.3223-3225.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boutolleau D, Duros C, Bonnafous P, Caiola D, Karras A, Castro ND, Ouachee M, Narcy P, Gueudin M, Agut H, Gautheret-Dejean A. Identification of human herpesvirus 6 variants A and B by primer-specific real-time PCR may help to revisit their respective role in pathology. J Clin Virol. 2006;35:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dewhurst S, McIntyre K, Schnabel K, Hall CB. Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) variant B accounts for the majority of symptomatic primary HHV-6 infections in a population of U. S. infants. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:416–418. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.416-418.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bates M, Monze M, Bima H, Kapambwe M, Clark D, Kasolo FC, Gompels UA. Predominant human herpesvirus 6 variant A infant infections in an HIV-1 endemic region of Sub-Saharan Africa. J Med Virol. 2009;81:779–789. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamanishi K, Okuno T, Shiraki K, Takahashi M, Kondo T, Asano Y, Kurata T. Identification of human herpesvirus-6 as a causal agent for exanthem subitum. Lancet. 1988;1:1065–1067. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91893-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yao K, Crawford JR, Komaroff AL, Ablashi DV, Jacobson S. Review part 2: Human herpesvirus-6 in central nervous system diseases. J Med Virol. 2010;82:1669–1678. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isaacson E, Glaser CA, Forghani B, Amad Z, Wallace M, Armstrong RW, Exner MM, Schmid S. Evidence of human herpesvirus 6 infection in 4 immunocompetent patients with encephalitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:890–893. doi: 10.1086/427944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tavakoli NP, Nattanmai S, Hull R, Fusco H, Dzigua L, Wang H, Dupuis M. Detection and typing of human herpesvirus 6 by molecular methods in specimens from patients diagnosed with encephalitis or meningitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3972–3978. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01692-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yao K, Honarmand S, Espinosa A, Akhyani N, Glaser C, Jacobson S. Detection of human herpesvirus-6 in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with encephalitis. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:257–267. doi: 10.1002/ana.21611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donati D, Akhyani N, Fogdell-Hahn A, Cermelli C, Cassiani-Ingoni R, Vortmeyer A, Heiss JD, Cogen P, Gaillard WD, Sato S, Theodore WH, Jacobson S. Detection of human herpesvirus-6 in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy surgical brain resections. Neurology. 2003;61:1405–1411. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000094357.10782.f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fotheringham J, Donati D, Akhyani N, Fogdell-Hahn A, Vortmeyer A, Heiss JD, Williams E, Weinstein S, Bruce DA, Gaillard WD, Sato S, Theodore WH, Jacobson S. Association of human herpesvirus-6B with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Challoner PB, Smith KT, Parker JD, MacLeod DL, Coulter SN, Rose TM, Schultz ER, Bennett JL, Garber RL, Chang M, Schad PA, Stewart PM, Nowinski RC, Brown JP, Burmer GC. Plaque-associated expression of human herpesvirus 6 in multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7440–7444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cermelli C, Berti R, Soldan SS, Mayne M, D'Ambrosia JM, Ludwin SK, Jacobson S. High frequency of human herpesvirus 6 DNA in multiple sclerosis plaques isolated by laser microdissection. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1377–1387. doi: 10.1086/368166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soldan SS, Berti R, Salem N, Secchiero P, Flamand L, Calabresi PA, Brennan MB, Maloni HW, McFarland HF, Lin HC, Patnaik M, Jacobson S. Association of human herpes virus 6 (HHV-6) with multiple sclerosis: increased IgM response to HHV-6 early antigen and detection of serum HHV-6 DNA. Nat Med. 1997;3:1394–1397. doi: 10.1038/nm1297-1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villoslada P, Juste C, Tintore M, Llorenc V, Codina G, Pozo-Rosich P, Montalban X. The immune response against herpesvirus is more prominent in the early stages of MS. Neurology. 2003;60:1944–1948. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000069461.53733.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buchwald D, Cheney PR, Peterson DL, Henry B, Wormsley SB, Geiger A, Ablashi DV, Salahuddin SZ, Saxinger C, Biddle R, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA, Folks T, Balachandran N, Peter JB, Gallo RC, Komaroff AL. A chronic illness characterized by fatigue, neurologic and immunologic disorders, and active human herpesvirus type 6 infection. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:103–113. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-2-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reeves WC, Stamey FR, Black JB, Mawle AC, Stewart JA, Pellett PE. Human herpesviruses 6 and 7 in chronic fatigue syndrome: a casecontrol study. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:48–52. doi: 10.1086/313908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallace HL nd, Natelson B, Gause W, Hay J. Human herpesviruses in chronic fatigue syndrome. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:216–223. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.2.216-223.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pellett PE, Sanchez-Martinez D, Dominguez G, Black JB, Anton E, Greenamoyer C, Dambaugh TR. A strongly immunoreactive virion protein of human herpesvirus 6 variant B strain Z29: identification and characterization of the gene and mapping of a variant-specific monoclonal antibody reactive epitope. Virology. 1993;195:521–531. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamamoto M, Black JB, Stewart JA, Lopez C, Pellett PE. Identification of a nucleocapsid protein as a specific serological marker of human herpesvirus 6 infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1957–1962. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.1957-1962.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higashimoto Y, Ohta A, Nishiyama Y, Ihira M, Sugata K, Asano Y, Peterson DL, Ablashi DV, Lusso P, Yoshikawa T. Development of a human herpesvirus 6 species-specific immunoblotting assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:1245–1251. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05834-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burbelo PD, Hoshino Y, Leahy H, Krogmann T, Hornung RL, Iadarola MJ, Cohen JI. Serological diagnosis of human herpes simplex virus type 1 and 2 infections by luciferase immunoprecipitation system assay. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16:366–371. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00350-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burbelo PD, Issa AT, Ching KH, Exner M, Drew WL, Alter HJ, Iadarola MJ. Highly quantitative serological detection of anti-cytomegalovirus (CMV) antibodies. Virol J. 2009;6:45. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burbelo PD, Bren KE, Ching KH, Gogineni ES, Kottilil S, Cohen JI, Kovacs JA, Iadarola MJ. LIPS arrays for simultaneous detection of antibodies against partial and whole proteomes of HCV, HIV and EBV. Mol Biosyst. 2011;7:1453–1462. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00342e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen JI, Jaffe ES, Dale JK, Pittaluga S, Heslop HE, Rooney CM, Gottschalk S, Bollard CM, Rao VK, Marques A, Burbelo PD, Turk SP, Fulton R, Wayne AS, Little RF, Cairo MS, El-Mallawany NK, Fowler D, Sportes C, Bishop MR, Wilson W, Straus SE. Characterization and treatment of chronic active Epstein-Barr virus disease: a 28-year experience in the United States. Blood. 2011;117:5835–5849. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-316745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burbelo PD, Leahy HP, Groot S, Bishop LR, Miley W, Iadarola MJ, Whitby D, Kovacs JA. Four-antigen mixture containing v-cyclin for serological screening of human herpesvirus 8 infection. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16:621–627. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00474-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burbelo PD, Issa AT, Ching KH, Wyvill KM, Little RF, Iadarola MJ, Kovacs JA, Yarchoan R. Distinct profiles of antibodies to Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus antigens in patients with Kaposi sarcoma, multicentric Castleman disease, and primary effusion lymphoma. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1919–1922. doi: 10.1086/652869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sashihara J, Hoshino Y, Bowman JJ, Krogmann T, Burbelo PD, Coffield VM, Kamrud K, Cohen JI. Soluble rhesus lymphocryptovirus gp350 protects against infection and reduces viral loads in animals that become infected with virus after challenge. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002308. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowman JJ, Lacayo JC, Burbelo P, Fischer ER, Cohen JI. Rhesus and human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein L are required for infection and cell -to-cell spread of virus but cannot complement each other. J Virol. 2011;85:2089–2099. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01970-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ravindran MK, Zheng Y, Timbol C, Merck SJ, Baraniuk JN. Migraine headaches in chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS): comparison of two prospective cross-sectional studies. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-11-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, Sharpe MC, Dobbins JG, Komaroff A. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:953–959. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burbelo PD, Ching KH, Klimavicz CM, Iadarola MJ. Antibody profiling by Luciferase Immunoprecipitation Systems (LIPS) J Vis Exp. 2009 doi: 10.3791/1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thader-Voigt A, Jacobs E, Lehmann W, Bandt D. Development of a microwell adapted immunoblot system with recombinant antigens for distinguishing human herpesvirus (HHV)6A and HHV6B and detection of human cytomegalovirus. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2011;49:1891–1898. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2011.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davenport FM, Hennessy AV, Francis T Jr. Epidemiologic and immunologic significance of age distribution of antibody to antigenic variants of influenza virus. J Exp Med. 1953;98:641–656. doi: 10.1084/jem.98.6.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]