Abstract

Several homology-dependent pathways can repair potentially lethal DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs). The first step common to all homologous recombination reactions is the 5′-3′ degradation of DSB ends that yields 3′ single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) required for loading of checkpoint and recombination proteins. The Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2/NBS1 complex and Sae2/CtIP initiate end resection while long-range resection depends on the exonuclease Exo1 or the helicase-topoisomerase complex Sgs1-Top3-Rmi1 with the endonuclease Dna21-6. DSBs occur in the context of chromatin, but how the resection machinery navigates through nucleosomal DNA is a process that is not well understood7. Here, we show that the yeast S. cerevisiae Fun30 protein and its human counterpart SMARCAD18, two poorly characterized ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers of the Snf2 ATPase family, are novel factors that are directly involved in the DSB response. Fun30 physically associates with DSB ends and directly promotes both Exo1- and Sgs1-dependent end resection through a mechanism involving its ATPase activity. The function of Fun30 in resection facilitates repair of camptothecin (CPT)-induced DNA lesions, and it becomes dispensable when Exo1 is ectopically overexpressed. Interestingly, SMARCAD1 is also recruited to DSBs and the kinetics of recruitment is similar to that of Exo1. Loss of SMARCAD1 impairs end resection, recombinational DNA repair and renders cells hypersensitive to DNA damage resulting from CPT or PARP inhibitor treatments. These findings unveil an evolutionarily conserved role for the Fun30 and SMARCAD1 chromatin remodelers in controlling end resection, homologous recombination and genome stability in the context of chromatin.

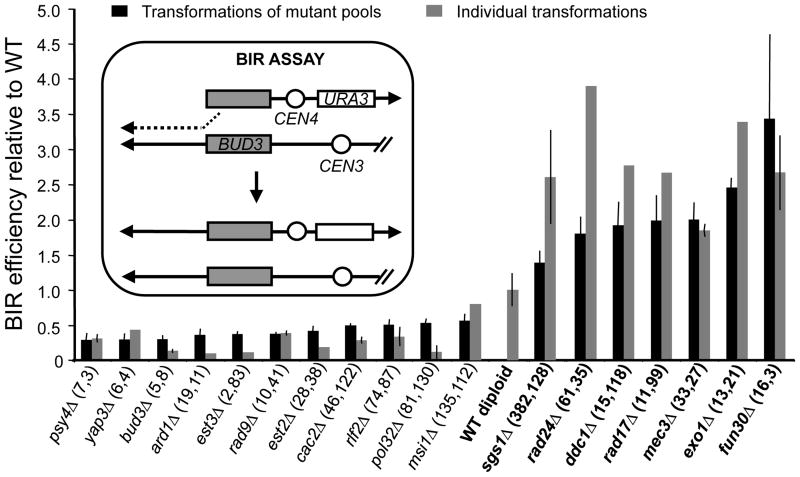

Fun30 (Function Unknown Now 30) possesses intrinsic ATP-dependent chromatin remodelling activity8, required to promote gene silencing in heterochromatin. FUN30 deletion renders cells hypersensitive to CPT9, whereas overexpression results in genomic instability10. However, a role for Fun30 in the DSB response remains enigmatic. While performing a genomic screen using a plasmid-based assay, we discovered that the fun30Δ mutant exhibits an increased efficiency of one-ended homologous recombination or break-induced replication (BIR) (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). We also found that gap repair, which is a two-ended homologous recombination reaction, is elevated in the fun30Δ mutant (Supplementary Fig. 2). This shows that Fun30 affects a step common to all homologous recombination reactions. Interestingly, the fun30Δ mutant shares this phenotype with the resection mutants sgs1Δ and exo1Δ1,2 in which impaired resection slows down degradation of transformed plasmids, favouring plasmid-based recombination11 (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Altogether, this suggests that Fun30 promotes DNA end-processing.

Figure 1. fun30Δ and DNA end-resection mutants show high BIR efficiencies.

BIR efficiencies of selected homozygous diploid null mutants relative to wild type (WT; BY4743). Mutants have been ranked according to their BIR efficiencies. Two BIR experiments using transformations of mutant pools were performed (Supplementary Fig. 1). The rank of each mutant in these two BIR experiments is given in parentheses. This rank is bottom-up for mutants with BIR efficiencies lower than wild type, and top-down otherwise. A schematic of the BIR assay is provided in the box. Error bars denote ± mean absolute deviation of two independent experiments.

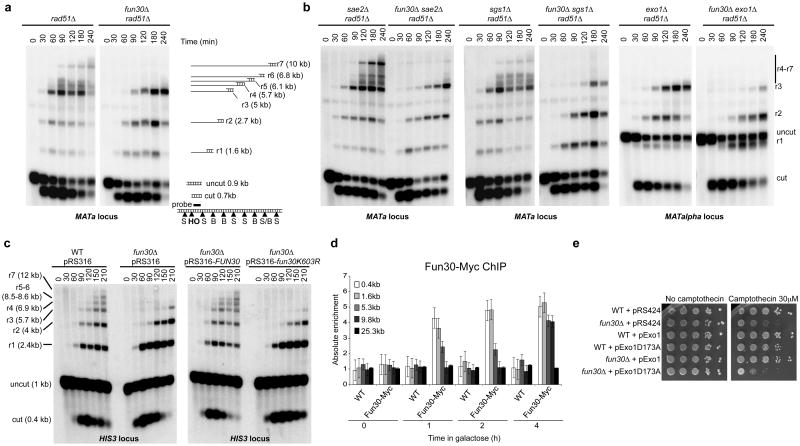

To test whether Fun30 contributes to 5′-3′ DNA end resection, we analysed ssDNA formation at an HO-induced DSB at the MAT locus12. Because ssDNA is resistant to cleavage by restriction enzymes, 5′-3′ resection at the DSB generates a ladder of ssDNA bands after restriction digestion of the genomic DNA and electrophoresis under alkaline conditions. In the absence of Fun30, the shortest ssDNA intermediate (r1) is formed with normal kinetics, but formation of longer ssDNA intermediates is either delayed (r2 and r3) or abolished (r4 to r7) (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 3). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) of ssDNA binding protein complex RPA at the HO-induced DSB confirmed these results (Supplementary Fig. 3c and d). Importantly, we detected a similar resection defect at an I-SceI cut site inserted at the HIS3 locus (Fig. 2c), ruling out a locus-specific effect. Overall, our results indicate that Fun30 facilitates long-range end resection. This is further supported by a delay in the kinetics of DSB repair by single strand annealing (SSA) in the fun30Δ mutant (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Figure 2. Fun30 promotes long-range 5′-3′ DNA end resection and is recruited to DSBs.

a, Southern blot analysis of StyI (S)/BstXI (B)-digested genomic DNA after alkaline gel electrophoresis. r1 to r7 fragments are partially ssDNA fragments. b, As in a, except that exo1Δ mutants were MATalpha strains, showing a longer uncut fragment (1.9 kb). c, Southern blot analysis of StyI-digested genomic DNA after alkaline gel electrophoresis to monitor ssDNA formation (r1-r7 fragments) at an I-SceI DSB generated at the HIS3 locus. d, Fun30-Myc levels at MAT before and after HO induction measured by ChIP coupled to qPCR. Error bars define the s.e.m. of three independent experiments. e, 10-fold serial dilutions of yeast cultures.

In the combined absence of Fun30 and either Sgs1 or Exo1, the resection defect was stronger than the defects in the corresponding single mutants (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 3b), leading to a more pronounced defect in RPA loading at the HO-induced DSB (Supplementary Fig. 3c). This correlated with higher plasmid-based BIR efficiencies and stronger delays in the kinetics of SSA (Supplementary Fig. 2 and 4). Altogether, these results demonstrate that Fun30 promotes both Sgs1- and Exo1-dependent resection of DSBs. Interestingly, we observed smeared cut fragments in the SSA assay in the fun30Δ exo1Δ mutant (Supplementary Fig. 4b). These indicate severely impaired long-range resection1, which may suggest that the Sgs1 resection pathway depends more strongly on Fun30 than does the Exo1 pathway.

The ATPase activity of Fun30 is essential for its chromatin remodelling activity8. Expression of wild-type Fun30, but not ATPase-dead Fun30K603R in fun30Δ restored end resection to wild-type levels (Fig 2c). This suggests that chromatin remodelling driven by Fun30 facilitates long-range resection, either directly or indirectly. Following induction of an HO DSB at MAT, Fun30 accumulated at sites near the DSB within 60 minutes and spread away at later time points (Fig. 2d), as previously observed for Sgs1, Dna2 and Exo12,13. This supports a direct role for Fun30 in long-range resection, acting in concert with the Exo1 and Sgs1 resection machineries. However, Fun30 could affect end resection indirectly by regulating gene transcription or by establishing an abnormal chromatin structure. Loss of Fun30 neither led to any significant change in transcript accumulation of end resection factors (Supplementary Fig. 5), nor did it affect nucleosome positioning at the HIS3 locus used to monitor resection (Supplementary Fig. 6). Together, these results implicate Fun30 in directly promoting long-range resection at DSBs. This conclusion is further supported by the fact that acute loss of Fun30 led to a long-range resection defect at the I-SceI break induced at the HIS3 locus (Supplementary Fig. 7). Interestingly, ChIP analysis of histones H3 and H2B occupancy around an HO DSB at MAT revealed that the loss of histone ChIP signal is coupled to long-range resection in WT and in fun30Δ cells (Supplementary Figures 8 and 9)14. This suggests that Fun30 does not facilitate long-range resection by modulating histone occupancy, but rather by increasing access to DNA within DSB-associated chromatin8.

We next investigated the physiological role of the resection function of Fun30. Gene conversion at a single HO DSB at MAT is normal in a fun30Δ mutant, both in the presence and absence of Sgs1 or Exo1 (data not shown). This shows that long-range resection is not essential for efficient gene conversion1,3. We confirmed that the fun30Δ mutant is hypersensitive to the topoisomerase I poison CPT, but not to the ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor hydroxyurea (HU) or ultraviolet (UV) light (Supplementary Fig. 10)9. Expression of wild type, but not ATPase-dead Fun30K603R in fun30Δ restored CPT resistance (Supplementary Fig. 10a), suggesting that resection driven by Fun30 ATPase activity protects cells against CPT-induced DNA damage. To directly show that the resection function of Fun30 is responsible for CPT resistance, we ectopically expressed Exo1 in a fun30Δ mutant. Expression of wildtype Exo1, but not the Exo1D173A nuclease dead mutant, suppressed both the resection defect and the CPT hypersensitivity of the fun30Δ mutant (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 11). This confirms that the resection function of Fun30 is required for the repair of CPT-induced DNA damage. Interestingly, the fun30Δ exo1Δ and fun30Δ sgs1Δ mutants are more sensitive to CPT, but not HU, than the fun30Δ, exo1Δ and sgs1Δ mutants (Supplementary Fig. 10b), which corroborates their stronger resection defects. However, the combined absence of Fun30 and Sae2 led to a synergistic hypersensitivity to both CPT and HU (Supplementary Fig. 10b), despite a resection defect that is comparable to that in the fun30Δ mutant (Figure 2b), suggesting that the roles of Fun30 and Sae2 in genome maintenance do not rely exclusively on facilitating resection15.

Resection mutants are known to affect the type of yeast survivors that form by different recombination mechanisms in the absence of functional telomerase16,17. Under liquid culture conditions, cells lacking the Est2 subunit of telomerase accumulate mostly type II survivors. However, we detected almost equal proportions of type I and type II survivors in a fun30Δ est2Δ mutant, similar to what is observed in other resection-defective mutants (rad24Δ, rad17Δ17 and exo1Δ16) (Supplementary Fig. 12a). Introduction of the cdc13-1 mutation that induces the formation of long ssDNA tracts at telomeres18 suppresses the fun30Δ est2Δ phenotype as it suppresses the phenotype of a rad17Δ est2Δ mutant17. Therefore, Fun30 affects recombination at unprotected telomeres most likely because of its role in resection.

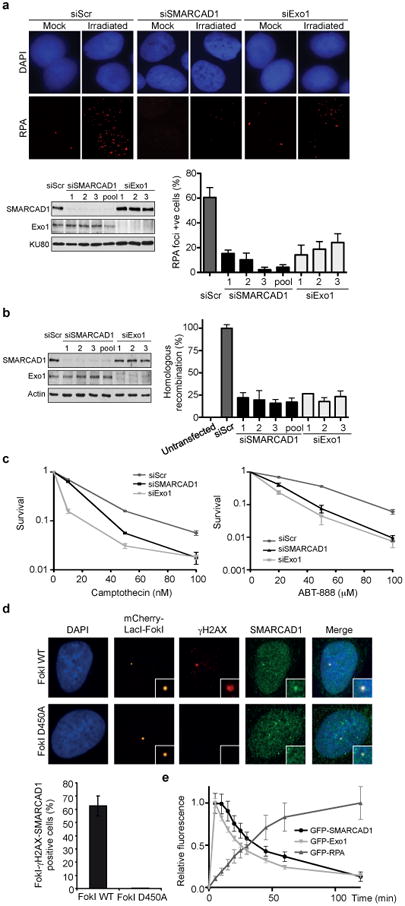

SMARCAD1 (SWI/SNF-related matrix-associated actin-dependent regulator of chromatin subfamily A containing DEAD/H box 1) is the human Snf2 family member that has the highest sequence similarity with Fun30. SMARCAD1 may function in the DNA damage response since it is phosphorylated at canonical (S/TQ) ATM/ATR phosphorylation sites, as well as at non-canonical sites, in response to genotoxic insults19,20. We examined whether SMARCAD1 also promotes DNA end resection. SMARCAD1 knockdown reduced the accumulation of RPA into ionizing radiation-induced foci (IRIF) (Fig. 3a), as well as that of GFP-tagged RPA at laser micro-irradiation-induced DSBs in U2OS cells21 (Supplementary Fig. 13a). Accordingly, we found that SMARCAD1 knockdown reduced ssDNA formation as determined by directly staining ssDNA-associated 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine IRIF (Supplementary Fig. 13b). These phenotypes are similar to those seen after Exo1 knockdown, a major resection enzyme in human cells21, indicating that the absence of SMARCAD1 impairs resection. In accord with a resection defect, we found that the loss of SMARCAD1 also impaired recombinational DSB repair. SMARCAD1 knockdown cells (i) were defective in the repair of an I-SceI-induced DSB by gene conversion in the DR-GFP reporter22 (Fig. 3b), (ii) showed a significant reduction in the repair of CPT-induced DSBs as monitored by the disappearance of 53BP1 foci in S/G2 phase cells (Supplementary Fig. 13c), and (iii) were hypersensitive to DNA damage resulting from CPT or PARP inhibitor (ABT-888) treatments (Fig. 3c). In addition, SMARCAD1 colocalized with γH2AX at laser-induced DNA damage and at DNA breaks generated by the FokI nuclease (Supplementary Fig. 13d and Fig. 3d), demonstrating that SMARCAD1 is recruited to DSBs. Importantly, GFP-tagged SMARCAD1 was recruited to laser micro-irradiation-induced lesions prior to GFP-tagged RPA and with kinetics similar to that of GFP-tagged Exo1 (Fig. 3e)21, as expected for a factor that promotes resection. Finally, the defect in RPA IRIF formation in SMARCAD1-depleted cells could be partially rescued by overexpression of human Exo1 (Supplementary Fig. 13e), indicating that SMARCAD1, like Fun30, plays a direct role in DNA end resection and recombinational DSB repair.

Figure 3. SMARCAD1 promotes end resection, homologous recombination and cell survival after genotoxic insults in U2OS cells.

a, Immunodetection (top) and quantification (lower right) of RPA foci 3 hr after 6 Gy of ionizing radiation. Western blot analysis of SMARCAD1 in cells transfected with individual or pooled siRNAs (lower left). Knockdown of Exo1 serves as a control. Nuclei with more than 10 RPA foci were scored. Error bars represent the s.e.m. of three independent experiments for all plots. b, Western blot analysis of SMARCAD1 (left) and quantification of homologous recombination frequencies using a DR-GFP assay (right). c, Clonogenic survival of SMARCAD1 knockdown cells treated with camptothecin or the PARP inhibitor ABT-888. d, Immunofluorescence staining of SMARCAD1 and γH2AX at DSBs induced by mCherry-LacI-FokI at a 256× LacO genomic array (top). Nuclease-deficient mCherry-LacI-FokI D450A was used as a control. Quantification of cells showing colocalization of SMARCAD1 and γH2AX at FokI-induced DSBs (bottom). e, Quantification of GFP-SMARCAD1, GFP-Exo1 and GFP-RPA accumulation at sites of laser micro-irradiation in live cells.

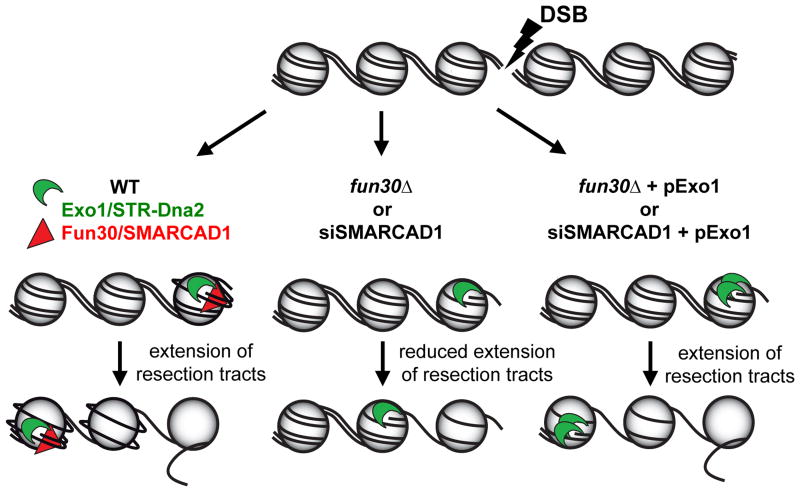

Recent reports from budding9 and fission23 yeast and human cells24 have shown that the Fun30/SMARCAD1 Snf2 family members play related roles in promoting heterochromatinization. We show that Fun30 and SMARCAD1 are novel DNA damage response proteins that facilitate DNA end resection and DSB repair in chromatin (Fig. 4). Their precise modes of action and the extent of their functional conservation remain to be determined.

Figure 4. Model for Fun30/SMARCAD1 control of end resection through DSB-associated nucleosomes.

Fun30/SMARCAD1 weaken histone-DNA interactions in nucleosomes flanking DSBs, which facilitates ssDNA production by the Exo1- and Sgs1/Top3/Rmi1 (STR)-Dna2 resection machineries. In the absence of Fun30/SMARCAD1 histone-DNA interactions limit the extent of resection, but plasmid-based overexpression of yeast or human Exo1 (pExo1), respectively, bypasses this impediment.

Methods summary

The yeast strains used are derivatives of S288C, W303 and JKM179 (see Supplementary Table 2). Details of their construction are provided in Supplementary Methods. The BIR genomic screen was adapted from25, except that pADW17 and pLS192 were used11. Tag arrays were from Chi Yip Ho (Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute, Toronto, Canada). The gap repair assay used pSB11026, which contains an ARS but no centromere. Detection of ssDNA intermediates, SSA assays and ChIP experiments were performed as in1,27. Transfection of U2OS cells, quantification of RPA foci after γ-irradiation, co-immunostaining for SMARCAD1 and γH2AX after laser micro-irradiation, and live-cell imaging of GFP-tagged proteins to laser-induced breaks were carried out as described21,28. SMARCAD1 localization studies at FokI-induced DSBs and DR-GFP assays were performed as previously reported22,29. Survival of U2OS cells after CPT or ABT-888 treatment was quantified by the standard colony formation assay.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Grzegorz Ira for sharing unpublished data, and Susan Janicki, Roger Greenberg, Lorraine Symington, and all the labs from the CNRS UPR3081 for providing reagents. We thank Stéphane Coulon for help in the analysis of the Fun30 repressible allele, Ingrid Lafontaine for support in statistical analyses, Cristel Vanessa Camacho for generating the V5-Exo1 constructs, and Aude Guénolé, Rohith Srivas, Trey Ideker, Kees Vreeken and Michiel Vermeulen for help in searching for Fun30 interactors. BL is grateful to Bernard Dujon for hosting him and providing the opportunity to perform the BIR screen. SB is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RO1 CA149461), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NNX10AE08G) and the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RP100644). HvA receives funding from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO-VIDI grant) and Human Frontiers Science Program (HFSP-CDA grant). BL is supported by grants from the CNRS (ATIP) and the “Agence Nationale de la Recherche” (ANR-10-BLAN-1606-03).

Footnotes

Author contributions: BL and AT performed the genetic screen and BL identified the resection defect of fun30Δ. TC constructed yeast strains and plasmids and performed the yeast ChIP experiments. RL constructed yeast strains, performed ssDNA analysis by alkaline gels, BIR and gap repair assays. RL and TC analyzed SSA defects. NT and BM performed all the SMARCAD1 knockdown experiments in human cells and the DR-GFP assays. EM designed and built the strain containing the inducible I-SceI cut site at HIS3, performed the microccocal nuclease assay, and contributed to data analysis. BK performed the analysis of survivors in the absence of telomerase. KD assisted RL and performed fun30Δ DNA damage sensitivity assays. WW examined the localization of SMARCAD1 at FokI-induced DSBs. TC, SB, HvA and BL designed the experiments and analyzed the data. HvA and BL wrote the manuscript.

Author Information: The microarray data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) and are accessible through GEO Series accession numbers GSE38715 (BIR screen) and GSE38735 (fun30Δ transcriptome). Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints. The authors declare no competing financial interests. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to bllorente@ifr88.cnrs-mrs.fr and h.van.attikum@lumc.nl.

References

- 1.Mimitou EP, Symington LS. Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double-strand break processing. Nature. 2008;455:770–774. doi: 10.1038/nature07312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu Z, Chung WH, Shim EY, Lee SE, Ira G. Sgs1 Helicase and Two Nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 Resect DNA Double-Strand Break Ends. Cell. 2008;134:981–994. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gravel S, Chapman JR, Magill C, Jackson SP. DNA helicases Sgs1 and BLM promote DNA double-strand break resection. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2767–2772. doi: 10.1101/gad.503108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cejka P, et al. DNA end resection by Dna2-Sgs1-RPA and its stimulation by Top3-Rmi1 and Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2. Nature. 2010;467:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature09355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicolette ML, et al. Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 and Sae2 promote 5′ strand resection of DNA double-strand breaks. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1478–1485. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niu H, et al. Mechanism of the ATP-dependent DNA end-resection machinery from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2010;467:108–111. doi: 10.1038/nature09318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sinha M, Peterson CL. Chromatin dynamics during repair of chromosomal DNA double-strand breaks. Epigenomics. 2009;1:371–385. doi: 10.2217/epi.09.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Awad S, Ryan D, Prochasson P, Owen-Hughes T, Hassan AH. The Snf2 homolog Fun30 acts as a homodimeric ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:9477–9484. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.082149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neves-Costa A, Will WR, Vetter AT, Miller JR, Varga-Weisz P. The SNF2-family member Fun30 promotes gene silencing in heterochromatic loci. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e8111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ouspenski II, Elledge SJ, Brinkley BR. New yeast genes important for chromosome integrity and segregation identified by dosage effects on genome stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3001–3008. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.15.3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marrero VA, Symington LS. Extensive DNA End Processing by Exo1 and Sgs1 Inhibits Break-Induced Replication. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White CI, Haber JE. Intermediates of recombination during mating type switching in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1990;9:663–673. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shim EY, et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 and Ku proteins regulate association of Exo1 and Dna2 with DNA breaks. EMBO J. 2010;29:3370–3380. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen CC, et al. Acetylated lysine 56 on histone H3 drives chromatin assembly after repair and signals for the completion of repair. Cell. 2008;134:231–243. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clerici M, Mantiero D, Lucchini G, Longhese MP. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sae2 protein negatively regulates DNA damage checkpoint signalling. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:212–218. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zubko MK. Exo1 and Rad24 Differentially Regulate Generation of ssDNA at Telomeres of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cdc13-1 Mutants. Genetics. 2004;168:103–115. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.027904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grandin N, Charbonneau M. Control of the yeast telomeric senescence survival pathways of recombination by the Mec1 and Mec3 DNA damage sensors and RPA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:822–838. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garvik B, Carson M, Hartwell L. Single-stranded DNA arising at telomeres in cdc13 mutants may constitute a specific signal for the RAD9 checkpoint. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6128–6138. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuoka S, et al. ATM and ATR Substrate Analysis Reveals Extensive Protein Networks Responsive to DNA Damage. Science. 2007;316:1160–1166. doi: 10.1126/science.1140321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beli P, et al. Proteomic Investigations Reveal a Role for RNA Processing Factor THRAP3 in the DNA Damage Response. Mol Cell. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomimatsu N, et al. Exo1 plays a major role in DNA end resection in humans and influences double-strand break repair and damage signaling decisions. DNA Repair (Amst) 2012;11:441–448. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolderson E, et al. Phosphorylation of Exo1 modulates homologous recombination repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:1821–1831. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strålfors A, Walfridsson J, Bhuiyan H, Ekwall K. The FUN30 chromatin remodeler, Fft3, protects centromeric and subtelomeric domains from euchromatin formation. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1001334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rowbotham SP, et al. Maintenance of Silent Chromatin through Replication Requires SWI/SNF-like Chromatin Remodeler SMARCAD1. Mol Cell. 2011;42:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ooi SL. A DNA Microarray-Based Genetic Screen for Nonhomologous End-Joining Mutants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 2001;294:2552–2556. doi: 10.1126/science.1065672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bärtsch S, Kang LE, Symington LS. RAD51 is required for the repair of plasmid double-stranded DNA gaps from either plasmid or chromosomal templates. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1194–1205. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.4.1194-1205.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Attikum H, Fritsch O, Gasser SM. Distinct roles for SWR1 and INO80 chromatin remodeling complexes at chromosomal double-strand breaks. EMBO J. 2007;26:4113–4125. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tomimatsu N, Mukherjee B, Burma S. Distinct roles of ATR and DNA-PKcs in triggering DNA damage responses in ATM-deficient cells. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:629–635. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shanbhag NM, Rafalska-Metcalf IU, Balane-Bolivar C, Janicki SM, Greenberg RA. ATM-Dependent Chromatin Changes Silence Transcription In cis to DNA Double-Strand Breaks. Cell. 2010;141:970–981. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.