Abstract

The data are relatively clear cut that palliative care improves quality of life and symptom control, improves quality of care by reducing aggressive but unsuccessful end of life care, and reduces costs. That should be an easy message to deliver to the public, health care administrators, payers, and governments. In fact, the arguments to develop palliative care services must be clear and concise, and make the clinical and financial case for the services that the palliative care team wants to deliver. Here, we discuss some of the types of models including consult services, outpatient programs, and inpatient units; the important components; some easy to use screening tools; components of the consultation team; a model medical record that increases “prompts” to do best palliative care; and data to report to supervisors.

Keywords: palliative care, clinical and financial case, screening tools, medical record

introduction

Palliative care is easily defined as careful attention to symptom management, open and honest communication, and medically appropriate goal setting. Palliative care is almost always interdisciplinary with nurses, social workers, chaplains or clergy, pharmacists, physicians and others having equal say in the care of the patient and family. Palliative care appears to improve care without harm (see reviews by Higginson [1], Zimmerman [2], Bruera [3], Temel [4] and the American Society of Clinical Oncology Provisional Clinical Opinion [5]). The exact methods by which palliative care improves patient results are not completely defined, but at least some components are necessary.

The purpose of this brief review is to define some of the important palliative care components, and give some guides to resource management. The ideas here are based on 20 years of experience in developing and sustaining palliative care units, and reflect the wisdom of many others including Diane Meier MD, MaryAnn Hager RN MSN, and Laurel Lyckholm RN MD.

what palliative care site and method gives the best results?

There are few data about what site or type of care provides the best outcomes. For the Center to Advance Palliative Care Curriculum Palliative Care Leadership Program we made a learning tool to identify appropriate palliative care model and staffing model. We found that teams had three types of care: 1. inpatient consult services only; 2. inpatient units (IP units) with or without consult services; and 3. outpatient clinic only. Of course, there are advantages and disadvantages to each as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of palliative care program models

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

| Consult Service and/or Outpatient Clinic | You can start quickly with a small staff | Usually only daytime coverage |

| Interdisciplinary collaboration throughout health system | You may not be in control of the care so the care may not change. Some programs have only 20% of their suggestions followed [15, 16] | |

| Low cost | May not be able to have ‘cost avoidance’ savings since patient care or location of care may not change, e.g. transfer out of the ICU May be difficult to obtain and track data unless you have a dedicated finance person | |

| Education is hospital wide | ||

| A consult service increased the number of appropriate discharges to hospice from 1% to about 30% [17], and from 25% to 47% in another. | Patients who transfer from palliative care to hospice may cost more than usual patients | |

| Inpatient Unit | ||

| A palliative care dedicated staff will provide the best care | The rest of the hospital may lose interest in palliative care since you are there | |

| With transfer to PCU, you assume control of the patient | You have control of the patient, so you must provide comprehensive, 24/7 care Some doctors may not want to give up control over their patients | |

| Becomes the place for education, clinical research, and volunteers | Must meet the hospital requirements for census, budget | |

| And a target for food, gifts, endowments | May be perceived as a ‘death unit’, or a sign that the clinician has ‘given up’ | |

| If you have admissions for pain and palliative care management, and engender trust, may make it easier to transition those patients to hospice type care. | ||

| Dedicated expert high volume care may be more efficient and less costly. | May be perceived as withholding disease specific treatment, such as feeding tubes |

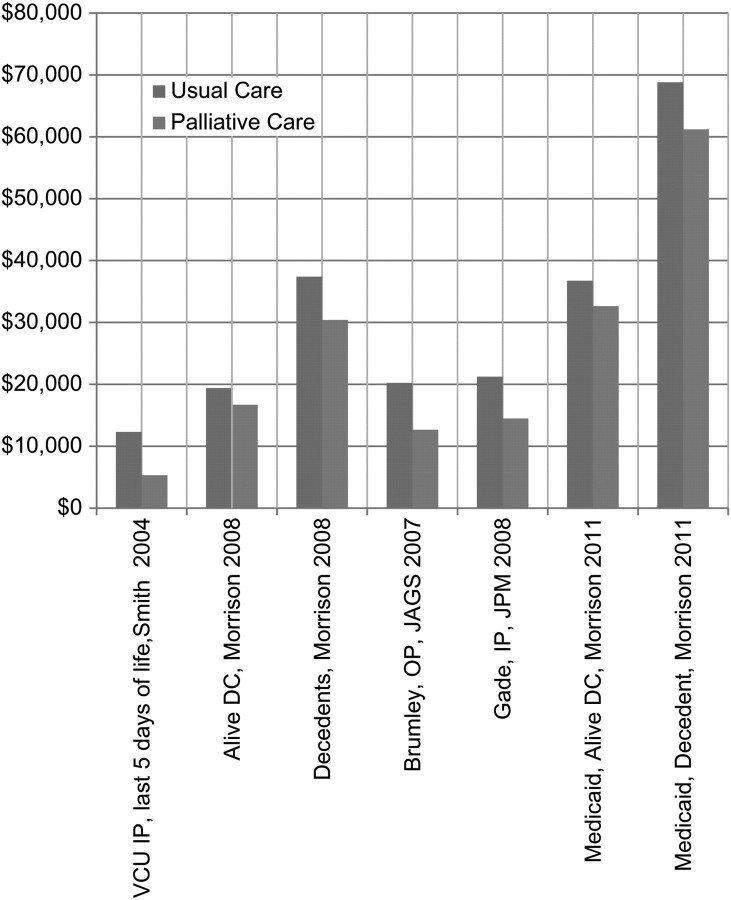

Inpatient palliative care units (PCUs) are devoted to providing only palliative care, with special nurses, training, and protocols just like the Intensive Care Unit. The advantages include specialized care, the ability to do certain procedures such as lidocaine or ketamine infusions, and it makes a visible ‘home’ for palliative care training, research, and donations. The disadvantage is that the PCU is a ‘cost center’ with a budget, and may be held to usual benchmarks such as 75% occupancy, and at least break even financially. To date, all the data show that palliative care saves money, as shown in Figure 1, with typical savings of US$5000–7500 per case.

Figure 1.

Impact of palliative care on health care costs. VCU IP, Virginia Commonwealth University Inpatients; Alive DC, patients discharged alive; Decedents, patients who died in the hospital; OP, outpatients; IP, inpatients.

Consult services are the easiest program to start and maintain. Consult services only need a health care professional to see patients and apply palliative care. Although we think of palliative care as fully interdisciplinary, there are no data that the full team is needed – or not. Muir et al. [6] did palliative care in oncology offices with ‘just’ a physician and advance practice nurse, and showed better symptom management. They set up the program this way because of reimbursement in the US which is only for doctors and nurses. They could have added a social worker who can bill for some counseling services. They showed a 21% decrease in symptom burden, an increase in oncologist satisfaction (necessary for them to continue to work with oncologists) and consults increased by 87% in 2 years. They saved each oncologist over 4 weeks of time so that the practice could do more regular oncology. In our own settings, chaplains do not get reimbursed, and psychologists may not be able to generate their own salary in billings, so most programs raise money to support these services. It is our opinion that these services are essential, and in our experience, patients and families greatly appreciate these ‘special’ types of care. For a recent review of oncologist–palliative care services see Alesi et al. [7].

The actual role of the consult service will vary with local customs and culture. Some consult services only make recommendations, whereas others actually assume care of the patient and write orders, take calls, etc. A ‘recommendation’ service is easier to start and maintain as it does not have long-term or intense responsibility. However, it may also not change practice much, especially at first, and loses the opportunity to standardize care with subsequent cost savings. The ‘assume care’ model requires more staff time to assume the care of medically complex patients, and must have arrangements for night and weekend coverage, but offers the strongest opportunity to create a model of standardized, medically appropriate, lower cost care. Those programs that want to advance palliative care earlier into the trajectory of care, i.e. during palliative chemotherapy treatment or during heart failure management, will need more staff and hours than those that concentrate on more traditional end-of-life care.

There is only one study that attempted to directly compare the experience with either consultation programs or inpatient palliative care units. Casarett et al. [8] interviewed 10 633 surviving caregivers after the death of their loved one in the US Veterans Administration system, with a response rate of 50–65%. Families of patients with usual care were less satisfied with the care over the last month of life than those who had a palliative care consultation, and those in the IP unit were the most satisfied. Patients with a palliative care consultation or IP unit stay had more ‘do not resuscitate’ orders, and they were obtained earlier before death. Other benefits included more chaplain visit and more goals of care discussion, all more common with palliative care consult and IP unit stays. This indicates a possible ‘dose-response’ effect familiar to oncologists – the more exposure to palliative care, the more palliation is actually achieved.

what are important components of a palliative care program?

We can identify some components which we think are important, including screening tools for consults and admissions, use of guidelines and standardized algorithms, use of a standard note for consults, and standardized metrics for comparison.

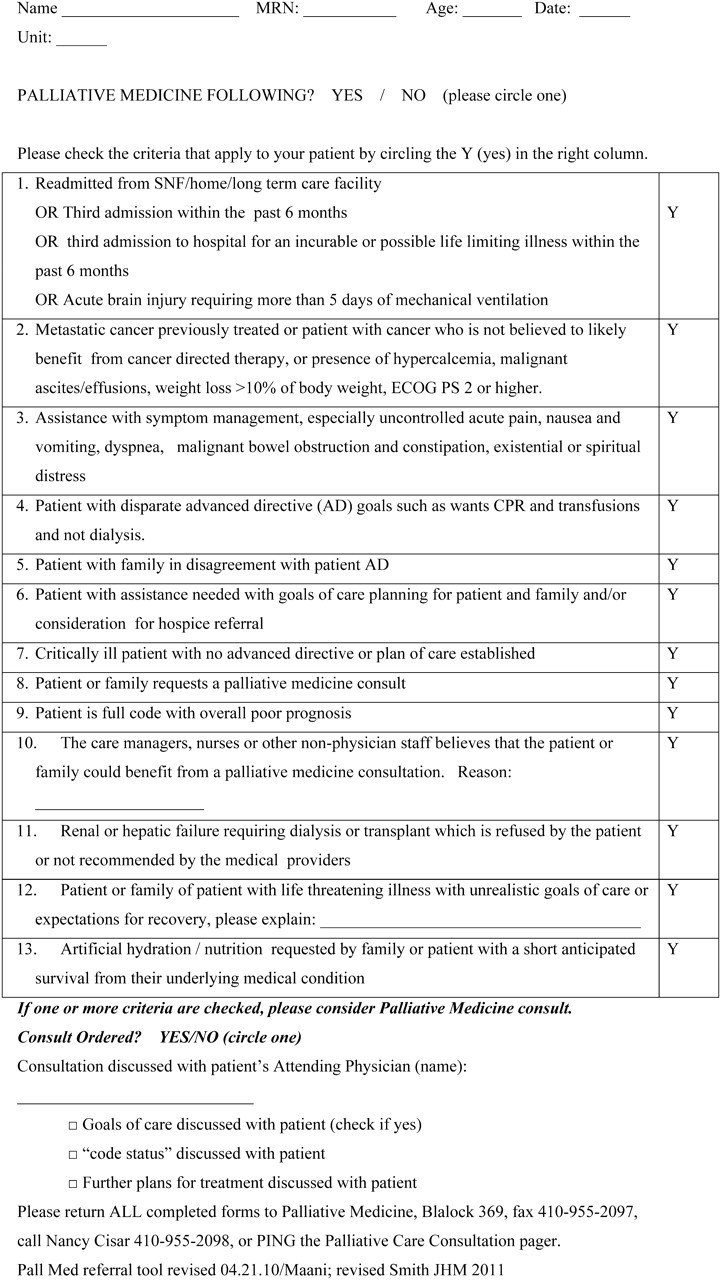

There are excellent screening tools available on the Center to Advance Palliative Care website (http://www.capc.org/tools-for-palliative-care-programs/clinical-tools/). We use a modification of the Geisenger Clinic Form, shown in Figure 2. Many algorithms that improve care are also available free of charge on the same website and can be modified for local use.

Figure 2.

Johns Hopkins Medicine Palliative Medicine Consult Worksheet. Adapted from the Geisenger Health System, developed by Dr Neil Ellison and colleagues. See also newly published trigger criteria [18].

The National Consensus Project [9] created guidelines that have been used in several studies with good results, especially that of Temel et al. [10] in non-small cell lung cancer which showed better palliation and 2.7 months more survival. Our modification is shown in Table 2, and includes ‘Always call the referring physician before discussing prognosis’.

Table 2.

Suggested components of a palliative care consultation (with comments or suggested phrases

| Understanding about illness understanding and the goals of care |

| Inquire about illness and prognostic understanding |

| “What do you want to know about your illness? What do you know about your situation?” |

| *After clearance by the attending physician, offer clarification of treatment goals |

| “Would you like to discuss what might happen to you?” |

| *Offer clarification of adaptation to changed goals and foreseeable death on several visits. Oncologists tend to think of this conversation as a one-time event, but the existential threat of death and loss of meaning continues from diagnosis. Personal Communication. Anthony Riley, MD, January 2012) |

| Inquire about uncontrolled symptoms Always use a Symptom Assessment Tool such as Edmonton or Memorial Sloan Kettering Scales |

| Pain |

| Pulmonary symptoms (cough, dyspnea) |

| Fatigue and sleep disturbance |

| Mood (depression and anxiety) |

| Gastrointestinal (anorexia and weight loss, nausea and vomiting, constipation) |

| Decision making |

| Inquire about mode of decision making |

| Assist with treatment decision-making, if necessary |

| Coping with life-threatening illness |

| “This must be hard on you and your family. How are you coping with this illness? |

| Patient |

| Family/family caregivers |

| Referrals/prescriptions |

| Identify – and write down - care plan for future appointments |

| Indicate referrals to other care providers, and communicate directly by fax, email, or electronic medical record |

| Note new medications prescribed |

*Modified from the National Palliative Care Consensus Guidelines, 2009

Table 3.

Data to gather in order to analyze your own performance, and compare to other PC programs

| Data element | Reason |

|---|---|

| Patient ID# | |

| Patient age, gender, race/ethnicity | Helps to know if you are reaching all the people you need to reach. |

| Palliative care diagnoses | List the top several for each patient |

| Referring service and/or referring physician | Helps to know who you are and are not reaching |

| Date of hospital admission | Helps to know your length of stay. Palliative care may reduce length of stay, which increases the number of people your hospital can serve. |

| Date of hospital discharge | |

| Date of PCU admission | |

| Disposition: inpatient death vs. discharge; discharge location | |

| Hospice admissions/discharges | |

| Patient billing status: acute care or hospice pass-through | |

| Financial analysis of the program | Are you profitable? Do you save money by cost avoidance? Do you cost the health system money? Do charitable donations support your program? Do you generate substantial good will for your parent organization? |

Modified from Center to Advance Palliative Care Metrics [13, 14]. PCU, palliative care unit.

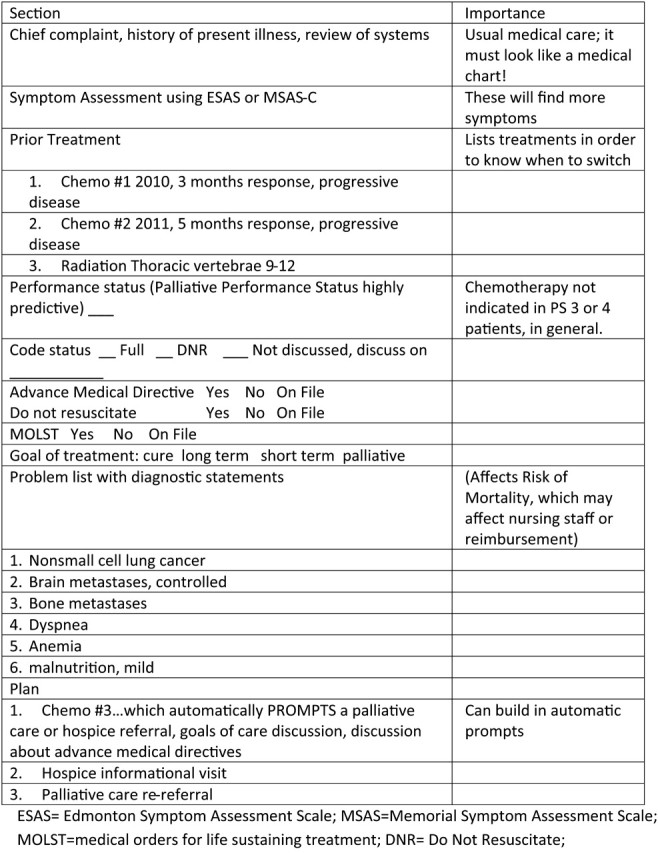

We have developed a standardized note with prompts. Prompts work [11], and prompts about advance medical directives can increase the number of discussions. Making a list of treatments done before helps us know when it is time to transition away from chemotherapy, such as three lines of chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer treatment. It appears to be almost universal that 10%–30% of patients receive chemotherapy in their last 2–4 weeks of life, regardless of profit motives of the oncologist [12], so we need better prompts to know when to have the discussion. One such note is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Template of a note to increase recording of oncology specific palliative care information.

Programs [13] should monitor their own performance for internal and external comparison. Weissman and Meier [14] have proposed standardized metrics, shown in modified form in Table 2. This data helps us determine who our customers are, and who is not referring to us, for selective marketing.

conclusions

Palliative care is a rapidly growing specialty that improves care at a cost we can afford, in every country. There are ways to structure the program and tools to enhance service. We illustrate some of these from our experience. Much research needs to be done to maximize efficiency and quality by directly comparing such methods, but there are ample ways to improve today.

acknowledgments

Research Support from ACS Grant #PEP-10-174-01 (TS), R01CA116227-01 (TJS), 2R01CA106370-05A1 (TJS), and RC2CA148259 (BEH) from the National Cancer Institute.

disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest on this topic.

references

- 1.Higginson IJ, Evans CJ. What is the evidence that palliative care teams improve outcomes for cancer patients and their families? Cancer J. 2010;16(5):423–435. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181f684e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimmermann C, Riechelmann R, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Effectiveness of specialized palliative care: a systematic review. JAMA. 2008;299(14):1698–1709. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.14.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruera E, Yennurajalingam S. palliative care in advanced cancer patients: how and when? The Oncologist. 2012 doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0219. Jan 17 [Epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0219. 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Jawahri A, Greer JA, Temel JS. Does palliative care improve outcomes for patients with incurable illness? A review of the evidence. J Support Oncol. 2011;9(3):87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Provisional Clinical Opinion: The Integration of Palliative Care into Standard Oncology Care. J Clinical Oncol. 2012;30:880–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muir JC, Daly F, Davis MS, et al. Integrating palliative care into the outpatient, private practice oncology setting. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(1):126–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alesi ER, Fletcher DS, Muir C, et al. Palliative care and oncology partnerships in real practice. Oncology (Williston Park) 2011;25(13):1287–1290. 1292–1293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casarett D, Johnson M, Smith D, Richardson D. The optimal delivery of palliative care: a national comparison of the outcomes of consultation teams vs. inpatient units. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(7):649–655. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrell B, Connor SR, Cordes A, et al. The national agenda for quality palliative care: the National Consensus Project and the National Quality Forum. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(6):737–744. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anton BB, Schafer JJ, Micenko A, et al. Clinical decision support. How CDS tools impact patient care outcomes. J Healthc Inf Manag. 2012;23(1):39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braga S. Why do our patients get chemotherapy until the end of life? Ann Oncol. 2011;22(11):2345–2348. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weissman DE, Meier DE, Spragens LH. Center to Advance Palliative Care palliative care consultation service metrics: consensus recommendations. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(10):1294–1298. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weissman DE, Meier DE. Center to advance palliative care inpatient unit operational metrics: consensus recommendations. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(1):21–25. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pantilat SZ, O'Riordan DL, Dibble S, Landefeld CS. Hospital-based palliative medicine consultation: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:2038–2040. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rabow MW, Dibble SL, Pantilat SZ, McPhee SJ. The comprehensive care team: a controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch Int Med. 2004;164:83–91. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morrison RS, Dietrich J, Ladwig S, et al. Palliative care consultation teams cut hospital costs for Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:454–463. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weissman DE, Meier DE. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: a consensus report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(1):17–23. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]