Abstract

Additional therapy with extracts of Viscum album [L.] (VaL) increases the quality of life of patients suffering from early stage breast cancer during chemotherapy. In the current study patients received chemotherapy, consisting of six cycles of cyclophosphamide, anthracycline, and 5-Fluoro-Uracil (CAF). Two groups also received one of two VaL extracts differing in their preparation as subcutaneous injection three times per week. A control group received CAF with no additional therapy. Six of 28 patients in one of the VaL groups and eight of 29 patients in the control group developed relapse or metastasis within 5 years. Subgroup analysis for hormone- and radiotherapy also showed no difference between groups. Additional VaL therapy during chemotherapy of early stage breast cancer patients appears not to influence the frequency of relapse or metastasis within 5 years.

Keywords: mistletoe therapy, chemotherapy, breast cancer, randomized clinical trial, disease-free survival rate, 5-year follow-up

Introduction

Background

Viscum album[L.] (VaL) extracts are widely used in cancer therapy in central Europe. In general, VaL is administered during and after conventional therapies like surgery, chemo-, hormone-, or radiotherapy and lasts for several years. Clinical evidence suggests that VaL influences the immune system1 and increases quality of life.2 Recently, a randomized trial examining VaL showed a significant and relevant prolongation of overall survival in late-stage pancreatic cancer patients compared to untreated controls.3 Therefore, VaL is claimed to be used in both adjuvant and palliative situations of cancer therapy.

Patients with early stage breast cancer regularly undergo chemotherapy after surgery in order to prevent relapse and metastasis. Often, the combination of cyclophosphamide, anthracycline, and 5-fluorouracil (CAF) is used. The side effects of these chemotherapies include nausea, emesis, pain, and fatigue. Fatigue is regarded as one of the major concerns for patients with cancer4 and is related to reduced activity, depression, anxiety, and mood disorders.5,6 Subcutaneous injection of VaL additionally applied to chemotherapy is regularly used to decrease chemotherapy side effects (e.g. neutropenia) and to increase the quality of life, and has been examined in twelve randomized clinical trials.7–18 Theoretically, higher quality of life and less neutropenia of patients receiving additional VaL therapy to chemotherapy may lead to the assumption that VaL reduces the toxicity (and with this, the efficacy) of chemotherapeutics. Although VaL increases the cytotoxicity of chemotherapy on malignant cells,19 additional VaL therapy is still under discussion. A clinical evaluation is overdue.

VaL therapy is traditionally continued after chemotherapy for several years in order to prevent relapses and metastases. Therefore, no documentation of relapse and metastasis exists that reports long-term results of the use of VaL limited to the duration of chemotherapy.

In a prospective randomized clinical trial, 95 patients suffering from early stage breast cancer were randomized into three groups.17 All three groups received chemotherapy consisting of six cycles of CAF. Two of the three groups received one of two VaL extracts from two different manufacturers in addition to the chemotherapy. Here we report the results of one of the VaL groups compared to the control group. Results of the other VaL group compared to the control group will be published elsewhere. The patients did not continue VaL therapy after the end of chemotherapy. The aim of the study was to show the impact of VaL therapy in addition to chemotherapy on quality of life, as assessed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC-QLQ-C30), as well as its impact on the frequency of neutropenia. In one of the groups treated with VaL extract, all 15 scores of the EORTC-QLQ-C30 showed better quality of life in the VaL group as compared to the control group. In 12 scores the differences were significant (P < 0.02), with nine scores showing a clinically relevant and significant difference of at least 5 points.17 Neutropenia occurred in 3/30 VaL patients and in 8/31 control patients (P = 0.182). None of the patients received VaL therapy after the end of chemotherapy, but some patients in both groups began hormone therapy or underwent radiotherapy. In this non-interventional 5-year follow-up, the frequency of relapses and metastases of all patients was documented.

Methods

Objectives

The objective of this 5-year follow-up study is to analyze whether VaL therapy in addition to chemotherapy has an influence on the median disease-free survival time as well as the total frequency of relapses and metastases in patients with early stage breast cancer.

Design

This is a prospective non-interventional follow-up study of two patient groups after participation in a randomized clinical trial. None of the patients received VaL extract after the end of the chemotherapy. Ethical approval was obtained from Institute for Oncology and Radiology of Serbia. All patients provided written informed consent before commencing participation.

Participants

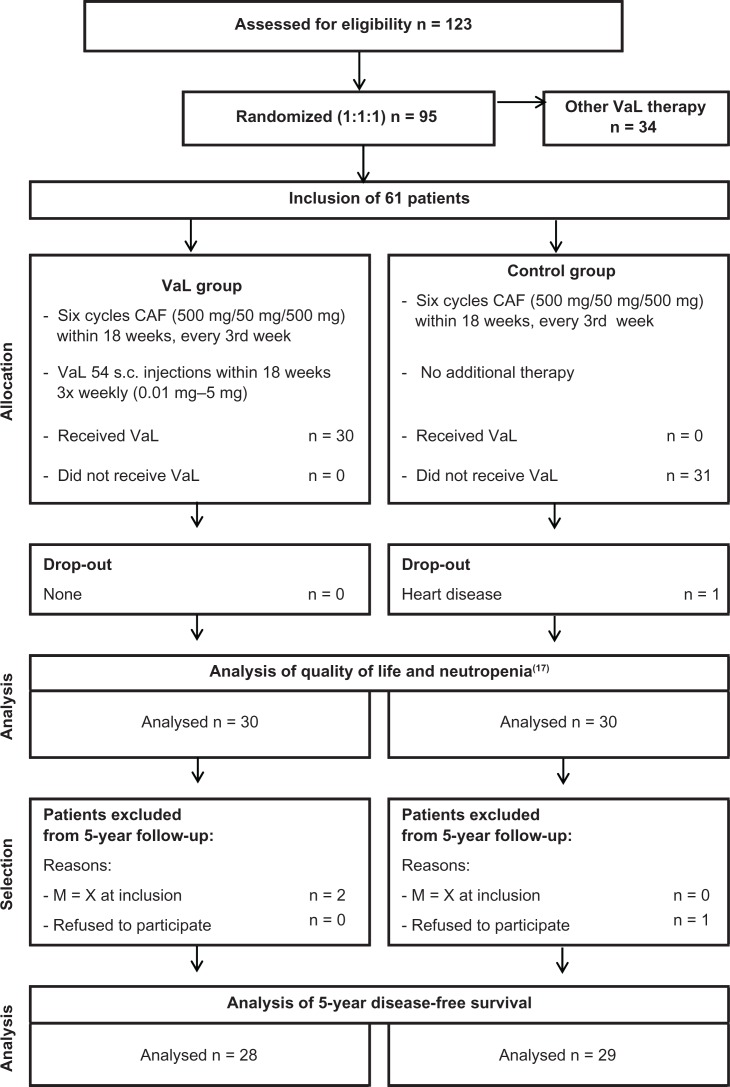

Breast cancer patients in stages T1–3N0–2M0 treated at the Institute of Oncology and Radiology, National Cancer Research Centre of Serbia in Belgrade who received six consecutive cycles of CAF after surgery were included. For participation in the long term follow-up, the following inclusion criteria were obligatory: patients should have had 6 cycles of chemotherapy, should definitively not have had metastases before the chemotherapy began, and should not have refused to participate in the study. Two patients in the VaL group had an unknown metastatic status (M = x) before the chemotherapy began, and one patient in the control group did not give her consent for continued participation. Therefore, we included 28 of 30 patients of the VaL group and 29 of 30 patients of the control group in this analysis (see Fig. 1). The follow-up began in June 2006 and ended in May 2012.

Figure 1.

Flow chart according to CONSORT.

Abbreviation: CAF, cyclophosphamide/adriamycin/5-fluorouracil.

Interventions

All patients have had CAF therapy administered in six cycles with a three-week interval between each cycle. The applied dose intensities (DI) of cyclophosphamide, Adriamycin, and 5-FU (DI in mean mg/m2 per week, ±standard deviation) were 160.5±5.6,16.1±0.6, and 160.5 ± 5.6, respectively, in the VaL group and 159.4±7.3, 15.9±0.7, and 159.4±7.3, respectively, in the control group. The results correspond to 98% of planned DI in the VaL group and 97% of planned DI in the control group. No other antineoplastic or immunomodulating therapies were applied during chemotherapy. All patients received antiemetic therapy with a single dose of ondansetron chloride 8 mg, dexamethasone 8 mg, and ranitidine 50 mg, respectively, administered prior to each CAF cycle.

Patients randomly allocated to additional therapy with VaL received Iscador®M special, a fermented aqueous extract of VaL from apple tree (ratio of plant to extract = 1:5), manufactured by Weleda AG, Schwäbisch Gmünd, Germany. VaL comes in 1 mL ampoules for injection and each ampoule contains the fermented extract of 0.01, 0.1, 1, 2, or 5 mg of fresh extract of VaL, respectively, in isotonic saline solution. VaL was administered by subcutaneous injections of 1 mL into the upper abdominal region three times per week (e.g. Monday, Wednesday, Friday). The patients in the VaL group were instructed to inject themselves subcutaneously. The dosage of VaL was increased stepwise: 2 × 0.01 mg, 2 × 0.1 mg, 11 × 1 mg, 8 × 2 mg, remaining doses 5 mg. An average of 53.8 ± 2.6 injections with altogether 174.0 ± 26.6 mg of VaL per patient were administered in the VaL group.

The control group did not receive additional VaL therapy to chemotherapy.

Outcomes

Occurrence of relapse and/or metastasis was documented annually up to 5 years during the prescribed routine follow-up visits of the study centre. The results were documented in case report forms designed for this study. A deviation of ±2 months was tolerated for the annual visits. The follow-up for an individual patient ended with the occurrence of a relapse or a metastasis.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis (StatExact V9.0, WinStat V2012.1) included all participating patients. All results are of exploratory nature and may serve for hypothesis building or sample size calculation. The Mann-Whitney test, Fisher’s exact test, Kruskal-Wallis test, and t-test were used to check the balance of demographic and clinical baseline characteristics as well as for the therapies after chemotherapy. The disease-free survival curves were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared between study groups using a log-rank test (Cox-Mantel).

Results

Baseline and treatment data

The baseline data of the two groups are well balanced (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline status.

|

Group

|

P values | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| VaL n = 28 | Control n = 29 | ||

| Age at inclusion | |||

| N patients | 28 (100%) | 29 (100%) | |

| Median | 47.5 | 52.9 | P(MWT) = 0.175 |

| Range | 35 to 61.6 | 32.5 to 66.8 | |

| Mean ± SD | 49.0 ± 7.8 | 51.8 ± 7.8 | P(TT) = 0.169 |

| BMI | |||

| N patients | 28 (100%) | 29 (100%) | |

| Median | 26.0 | 25.6 | P(MWT) = 0.444 |

| Range | 18.9 to 52.1 | 18.7 to 33.4 | |

| Mean ± SD | 27.0 ± 6.3 | 25.5 ± 4.7 | P(TT) = 0.316 |

| Karnofsky | P(FET) = 1.000 | ||

| 100 | 28 (100%) | 29 (100%) | |

| Stage (UICC) | P(KWT) = 0.990 | ||

| I | 2 (7%) | 4 (14%) | |

| II | 25 (89%) | 22 (76%) | |

| III | 1 (4%) | 3 (10%) | |

| Tumour classification T | P(KWT) = 0.594 | ||

| 1 | 6 (21%) | 9 (31%) | |

| 2 | 20 (71%) | 17 (59%) | |

| 3 | 1 (4%) | 2 (7%) | |

| X | 1 (4%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Positive lymph nodes N | P(KWT) = 0.200 | ||

| 0 | 10 (36%) | 16 (55%) | |

| 1 | 18 (64%) | 12 (41%) | |

| 2 | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Metastasis M | P(FET) = 1.000 | ||

| 0 | 28 (100%) | 29 (100%) | |

| Tumour grade G | P(KWT) = 1.000 | ||

| 1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 2 | 24 (86%) | 24 (83%) | |

| 3 | 4 (14%) | 5 (17%) | |

| LN taken out | P(MWT) = 0.762 | ||

| Median | 15 | 15 | |

| Range | 5 to 22 | 8 to 32 | |

| N patients | 28 (100%) | 29 (100%) | |

| LN affected | P(MWT) = 0.641 | ||

| Median | 1 | 1 | |

| Range | 0 to 8 | 0 to 8 | |

| N patients | 28 (100%) | 29 (100%) | |

| Menopausal status | P(FET) = 0.407 | ||

| Pre | 15 (54%) | 11 (38%) | |

| Peri | 2 (7%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Post | 11 (39%) | 17 (59%) | |

| Receptor status oestrogen | P(FET) = 0.545 | ||

| + | 19 (68%) | 16 (55%) | |

| − | 7 (25%) | 11 (38%) | |

| n.d. | 2 (7%) | 2 (7%) | |

| Receptor status progesterone | P(FET) = 1.000 | ||

| + | 17 (61%) | 18 (62%) | |

| − | 9 (32%) | 9 (31%) | |

| n.d. | 2 (7%) | 2 (7%) | |

Abbreviations: MWT, Mann-Whitney-test; TT, t-test; FET, Fisher’s exact test, KWT, Kruskal-Wallis-test.

After chemotherapy and VaL therapy ended, patients underwent other therapies, which may have influenced the disease-free survival rate. Therefore, other therapies were documented in both groups. The most frequent therapies were adjuvant radiotherapy (n = 37) and anti-hormonal therapy (tamoxifen; n = 32; Table 2). Both therapies were well balanced between the study groups and have been analyzed as separate subgroups (Figs. 3 and 4). Other therapies were trastuzumab (n = 4), goserelin (n = 2), docetaxel (n = 1), and letrozole (n = 1; Table 2). The latter therapies in total were also well balanced between the groups, but their frequency of application was too small to represent subgroups for an analysis.

Table 2.

Therapies after chemotherapy (CAF).

|

Group

|

P values | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| VaL n = 28 | Control n = 29 | ||

| Radiotherapy | P(FET) = 0.783 | ||

| Radiotherapy (50 Gray) | 19 (68%) | 18 (62%) | |

| None | 9 (31%) | 11 (39%) | |

| Tamoxifen | P(FET) = 0.289 | ||

| Tamoxifen (20 mg/d) | 18 (64%) | 14 (48%) | |

| None | 10 (36%) | 15 (52%) | |

| Other therapies | P(FET) = 0.730 | ||

| Other therapies | 5 (18%) | 4 (14%) | |

| None | 23 (82%) | 25 (86%) | |

Abbreviation: FET, Fisher’s exact test.

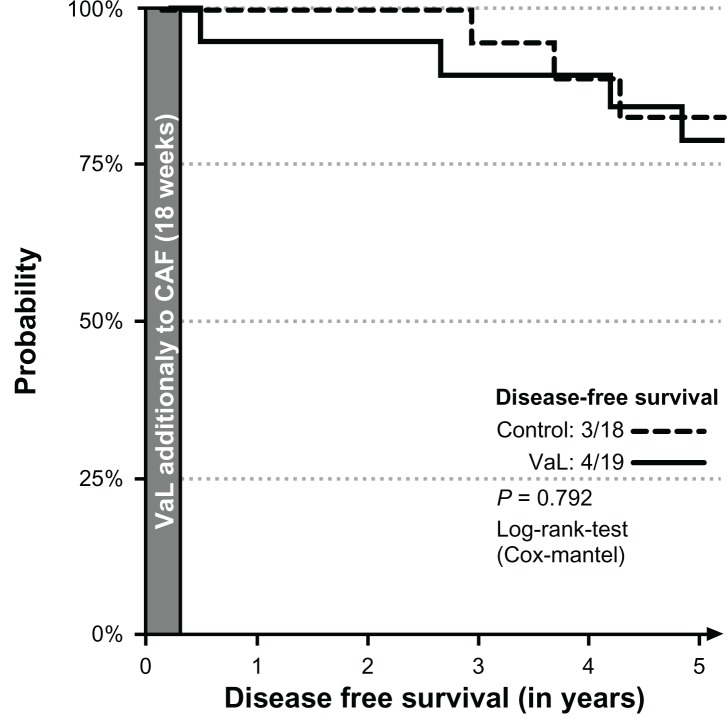

Figure 3.

Disease-free interval of patients receiving radiotherapy.

Figure 4.

Disease-free interval of patients receiving tamoxifen.

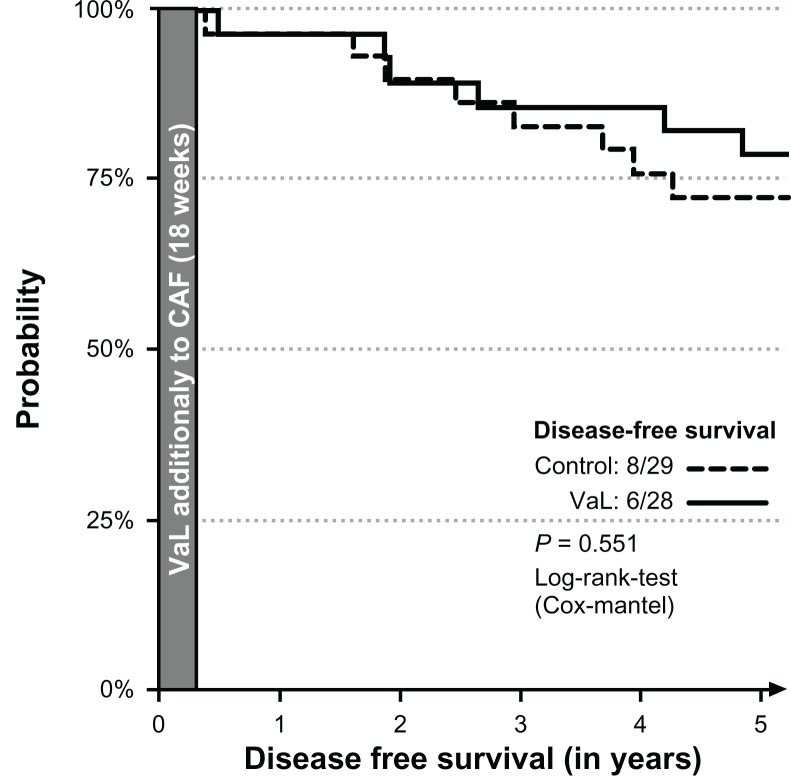

Disease-free survival

The median disease-free survival time could not be calculated, because the highest probability for relapse or metastasis in 5 years was 28%. The disease-free 5-year survival rates were 6/28 and 8/29 patients in the VaL and the control groups, respectively (Fig. 2). The difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.551; Cox-Mantel log-rank test).

Figure 2.

Disease-free interval of all patients.

The subgroup analysis of patients undergoing radiotherapy yielded 4/19 and 3/18 patients in the VaL and the control group, respectively (Fig. 3); the subgroup analyses of patients with anti-hormonal therapy yielded 4/18 and 4/14 patients in the VaL and control group, respectively (Fig. 4). None of the differences were statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test P = 0.792 and P = 0.659, respectively).

Discussion

No studies have examined the impact of medicaments like analgesics, antiemetics, antibiotics or VaL routinely used in parallel to chemotherapy, taking relapse and metastasis into consideration. In the case of VaL, patients reported an increase in quality of life, and a reduction of neutropenia was detected during the additional use of VaL during chemotherapy. Therefore, it may be assumed that the reduction of the clinical toxicity of the chemotherapy also leads to a reduction of its efficacy. In this study the additional VaL therapy during chemotherapy of patients with early stage breast cancer did not affect the 5-year disease-free survival rate compared to a control group receiving chemotherapy alone, and also yielded no indication that subsequently started therapies were influenced in any way. Moreover, the clinical benefit of additional VaL therapy during chemotherapy may prevent patients from dropping out or delaying chemotherapy cycles. Speculations about a possible negative impact of additional VaL therapy on the efficacy of the chemotherapy are not founded. On the contrary: VaL increases the cytotoxicity of chemotherapeutics if added in cell culture assays; VaL and chemotherapeutics have been used with good results since decades and this prospective study shows no disadvantages of the additional use of VaL to chemotherapy during a 5-year follow-up regarding relapses and metastases.

A strength of this study is that VaL treatment only occurs for the duration of chemotherapy. Because of this strength, results cannot be biased by a continuation of VaL therapy, which may have had a further impact on the disease free survival rate.

The low sample size used in this study limits its generalizability, and calls for confirmation using larger clinical trials. A statistical confirmation of non-inferiority for combined VaL/chemotherapy compared to chemotherapy alone would require about 1,000 patients per group.20

The results suggest that there is a small advantage from VaL therapy in the number of disease-free patients after five years. This advantage may be due to a slight prognostic advantage for the patients in the VaL group regarding age, frequency of UICC (III, T = 3, N > 0, G = 3), and receptor status (oestrogen = negative). As no differences in the frequency of relapse and metastasis occurred in both groups regarding these factors, therefore, only the difference in age (2.8 years) may have influenced results (Table 3).

Table 3.

Outcomes of patients with different relevant prognosis factors.

| Prognostic factor |

Number of patients with events

|

|

|---|---|---|

|

Group

| ||

| VaL | Control | |

| UICC = 3 | – | – |

| T (TNMG) = 3 | – | – |

| N (TNMG) > 0 | 4 | 4 |

| G (TNMG) = 3 | – | – |

| Receptor status oestrogen = negative | 1 | 1 |

The study results support the use of VaL therapy in addition to chemotherapy, in contrast to objections against this type of treatment. Further research on drug combinations should be conducted.

Conclusion

VaL therapy in addition to chemotherapy increases the quality of life of patients with early stage breast cancer and may prevent neutropenia. In the current study no negative influence of additional Val therapy on the effectiveness of chemotherapy of patients with early stage breast cancer was detected, referring to the frequency of relapse or metastasis within 5 years.

Acknowledgments

We like to thank the participating patients and the study nurse Z. Ranđeljović.

Footnotes

Funding

The study was financially supported by the Society for Cancer Research, Arlesheim, Switzerland.

Author Contributions

MM and ZZ were investigators. NS carried out the monitoring and quality assurance, WT was the principal author of the paper, wrote the study protocol, coordinated the study, had full access to all data, and is guarantor. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

Author(s) disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Ethics

The sponsor had no influence on study design, planning, conduct or analysis. Besides the approval of the Ethics Committee of the National Cancer Research Center of Serbia without modifications (No. 16-05 dated: 3rd October 2005) no further decision was necessary for this non-interventional observation study.

References

- 1.Büssing A. Immune modulation using mistletoe (Viscum album L.) extracts Iscador. Arzneimittelforschung. 2006;56(6A):508–15. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1296818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kienle GS, Kiene H. Influence of Viscum Album L. (European Mistletoe) extracts on quality of life in cancer patients: a systematic review of controlled clinical studies. Integr Cancer Ther. 2010;9(2):142–57. doi: 10.1177/1534735410369673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galun D, Tröger W, Reif M, Schumann A, Stankovic N, Milicevic M. Mistletoe extract therapy versus no antineoplastic therapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: a randomized clinical phase III trial on overall survival. Annals of Oncology. 2012;23(Suppl 9):ix237. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butt Z, Rosenbloom SK, Abernethy AP, et al. Fatigue is the most important symptom for advanced cancer patients who have had chemotherapy. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2008;6(5):448–55. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2008.0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Jong N, Candel MJ, Schouten HC, Abu-Saad HH, Courtens AM. Course of mental fatigue and motivation in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(3):372–82. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldstein D, Bennett B, Friedlander M, Davenport T, Hickie I, Lloyd A. Fatigue states after cancer treatment occur both in association with, and independent of, mood disorder: a longitudinal study. BMC Cancer. 2006 Oct 9;6(1):240. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auerbach L, Dostal V, Václavik-Fleck I, et al. Signifikant höherer Anteil aktivierter NK-Zellen durch additive Misteltherapie bei chemotherapierten Mamma-Ca-Patientinnen in einer prospektiven randomisierten doppelblinden Studie. In: Scheer R, Bauer R, Becker H, Fintelmann V, Kemper FH, Schilcher H, editors. Fortschritte in der Misteltherapie. Aktueller Stand der Forschung und klinischen Anwendung. Essen: KCV Verlag; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douwes FR, Wolfrum DI, Migeod F. Ergebnisse einer prospektiv randomisierten Studie: Chemotherapie versus Chemotherapie plus “Biological Response Modifier” bei metastasierendem kolorektalen Karzinom. Krebsgeschehen. 1986;18(6):155–63. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douwes FR, Kalden M, Frank G, Holzhauer P. Behandlung des fortgeschrittenen kolorektalen Karzinoms. Dtsch Zschr Onkol. 1988;20(3):63–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisenbraun J, Huber R, Kröz M, Schad F, Scheer R. In: Lebensqualität von Brustkrebs-Patientinnen während der Chemotherapie und einer begleitenden Therapie mit einem Apfelbaum-Mistelextrakt. Scheer R, Alban S, Becker H, Holzgrabe U, Kemper FH, Kreis W, editors. Essen: KVC Verlag; 2009. Die Mistel in der Tumortherapie 2. Aktueller Stand der Forschung und klinische Anwendung. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutsch J, Kühne A. Pharmakologische und klinische Erfahrung mit dem Mistelextrakt Helixor. Die Heilkunst. 1986;99:156–72. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loewe-Mesch A, Kuehn JH, Borho K, et al. Adjuvante simultane Mistel-/Chemotherapie bei Mammakarzinom—Einfluss auf Immunparameter, Lebensqualität und Verträglichkeit. Forschende Komplementärmedizin. 2008;15(1):22–30. doi: 10.1159/000112860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piao BK, Wang YX, Xie GR, et al. Impact of complementary mistletoe extract treatment on quality of life in breast, ovarian and non-small cell lung cancer patients. A prospective randomized controlled clinical trial. Anticancer Res. 2004;24(1):303–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salzer G, Denck H. Randomisierte Studie über medikamentöse Rezidivprophylaxe mit 5-Fluorouracil und Iscador beim resezierten Magen-karzinom—Ergebnisse einer Zwischenauswertung. Krebsgeschehen. 1979;11(5):130–1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salzer G, Havelec L. Adjuvante Iscador-Behandlung nach operiertem Magenkarzinom. Ergebnisse einer randomisierten Studie. Krebsgeschehen. 1983;15(4):106–10. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salzer G, Danmayr E, Wutzlhofer F, Frey S. Adjuvante Iscador-Behandlung operierter nicht kleinzelliger Bronchuskarzinome. Dtsch Zschr Onkol. 1991;23(4):93–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tröger W, Jezdic S, Zdrale Z, Tisma N, Hamre HJ, Mattijasevic M. Quality of life and neutropenia in patients with early stage breast cancer: a randomized pilot study comparing additional treatment with mistletoe extract to chemotherapy alone. Breast Cancer: (Auckl) 2009;3:35–45. doi: 10.4137/bcbcr.s2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Hagens A, Loewe-Mesch A, Kuehn JJ, Abel U, Gerhard I. Prospektive kontrollierte nicht randomisierte Machbarkeits-Studie zu einer post-operativen simultanen Mistel-/Chemotherapie bei Patientinnen mit Mammakarzinom—Ergebnisse zu Rekrutier- und Randomisierbarkeit, Immunparametern, Lebensqualität und Verträglichkeit. In: Scheer R, Bauer R, Becker H, Fintelmann V, Kemper FH, Schilcher H, editors. Fortschritte in der Misteltherapie. Aktueller Stand der Forschung und klinischen Anwendung. Essen: KCV Verlag; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Büssing A, Jurin M, Zarkovic N, Azhari T, Schweizer K. DNA- stabilisierende Wirkungen von Viscum album L.—Sind Mistelextrakte als Adjuvans während der konventionellen Chemotherapie indiziert? Forsch Komplementärmed Klass Naturheilkd. 1996;3:244–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schoenfeld DA. The asymptotic properties of nonparametric tests for comparing survival distributions. Biometrika. 1981;68:316–9. [Google Scholar]