Abstract

The cultivated tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) has a unipinnate compound leaf. In the developing leaf primordium, major leaflet initiation is basipetal, and lobe formation and early vascular differentiation are acropetal. We show that engineered alterations in the expression of a tomato homeobox gene, LeT6, can cause dramatic changes in leaf morphology. The morphological states are variable and unstable and the phenotypes produced indicate that the tomato leaf has an inherent level of indeterminacy. This is manifested by the production of multiple orders of compounding in the leaf, by numerous shoot, inflorescence, and floral meristems on leaves, and by the conversion of rachis-petiolule junctions into “axillary” positions where floral buds can arise. Overexpression of a heterologous homeobox transgene, kn1, does not produce such phenotypic variability. This indicates that LeT6 may differ from the heterologous kn1 gene in the effects manifested on overexpression, and that 35S-LeT6 plants may be subject to alterations in expression of both the introduced and endogenous LeT6 genes. The expression patterns of LeT6 argue in favor of a fundamental role for LeT6 in morphogenesis of leaves in tomato and also suggest that variability in homeobox gene expression may account for some of the diversity in leaf form seen in nature.

During vegetative growth most higher plants are indeterminate. The SAM produces a radially symmetrical, acropetally differentiating shoot axis (stem) and determinate, bilaterally symmetrical lateral organs (leaves). Leaves can be one of two types, simple or compound, and the nature of these has been a matter of debate. The ontogenetic relationship of the dicot compound leaf to the simple leaf is unclear (Merrill, 1986), with various researchers concluding that the basic leaf form is simple (Eames, 1961) or compound pinnate (Hagemann, 1984), or that compound leaves have some shoot-like features and may represent a continuum between shoots and leaves (Sattler and Rutishauser, 1992; Lacroix and Sattler, 1994).

To determine morphogenetic patterns and the level of indeterminacy in compound leaves, we have used homeobox genes that were cloned from tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) (Chen et al., 1997; Janssen et al., 1998). Homeobox genes encode transcription factors that control the regulation of cell fate (McGinnis et al., 1984; Scott et al., 1989). The first plant homeobox gene cloned was the maize knotted1 (kn1) gene (Vollbrecht et al., 1991). kn1-like homeobox (knox) genes have been placed into two classes (Kerstetter et al., 1994). Although no specific function has as yet been ascertained for class II knox genes (Serikawa et al., 1997), class I knox genes play a role in meristem maintenance and leaf and flower determination at the shoot apex. Class I knox genes are not expressed in initiating organ primordia, mature leaves, or floral organs in simple-leaved species (Smith et al., 1992; Jackson et al., 1994; Long et al., 1996).

We have cloned a class I knox gene, LeT6 (L. esculentum T6), and shown that it is expressed in floral and vegetative shoot apices and also in leaf and floral organ primordia (Chen et al., 1997; Janssen et al., 1998). This gene has also been referred to as Tomato knotted2 (Tkn2) by Parnis and coworkers (1997). The Tkn1 gene, also a class I knox gene, similarly shows expression in leaf and floral organ primordia of tomato (Hareven et al., 1996). Thus, in maize (Zea mays) and Arabidopsis thaliana, which have simple leaves, the class I knox genes are not expressed in initiating leaf primordia, whereas in tomato, which has a compound leaf, they are (Sinha, 1997).

The tomato leaf primordium produces major leaflet primordia in a basipetal sequence, and these give rise to lobed leaflets (Dengler, 1984; Coleman and Grayson, 1976). Minor leaflets are produced nonbasipetally, and early vascular differentiation follows an acropetal sequence (Coleman and Grayson, 1976). We see LeT6 expression in the preprimordium stage and in the initiating leaf primordia at the shoot apex (Chen et al., 1997). If class I knox genes are involved in morphogenesis of the compound leaf through their expression in developing leaf primordia, what might be the consequences of expressing a class I knox gene in mature leaves? Overexpression of the maize kn1 gene leads to lobed leaves in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) (Sinha et al., 1993) and Arabidopsis (Lincoln et al., 1994), and causes excessive leaflet proliferation in tomato (Hareven et al., 1996). When the Arabidopsis class I knox gene Knat1 is overexpressed in Arabidopsis, stipules are produced in the sinuses of highly lobed leaves, and ectopic shoots or floral primordia are seen (Chuck et al., 1996).

Our phylogenetic analyses indicate that LeT6 is a possible ortholog of the stm1 gene, whereas neither Tkn1 nor stm1 are orthologous to kn1 (G. Bharathan, B.-J. Janssen, E.A. Kellogg, and N. Sinha, unpublished data). It was unclear if there would be phenotypic differences between 35S-LeT6 and 35S-kn1 overexpression in tomato, since one is a class I knox gene from a compound-leaved plant (LeT6), whereas the other originates from a simple-leaved plant (kn1). The fact that these are not orthologous genes and that expression of a homologous transgene (LeT6) could result in cosuppression phenotypes suggested that we might find novel morphological consequences from overexpression of LeT6. Therefore, we generated transgenic tomato plants that overexpressed LeT6. The phenotypes in 35S-LeT6 tomato plants showed great variability. Novel phenotypes not described for 35S-kn1 tomato plants (Hareven et al., 1996) were seen. These phenotypes not only indicated a role for LeT6 in leaf morphogenesis, but also revealed the possible morphogenetic potential of the tomato compound leaf.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transgenic Methods

LeT6 cDNA was cloned between the “double” CaMV 35S 5′ region and the polyadenylation region from the Tml gene in the vector pCGN2187 (Comai et al., 1990). This chimeric gene was then cloned into the binary vector pCGN1549. pCGN1549 differs from pCGN1547 only in the direction of transcription of the NptII gene and in the order of sites in the polylinker. The empty pCGN1547 vector has been used in control tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum cv NC8276) transformations (McBride and Summerfelt, 1990). The LeT6 construct in pCGN1549 was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LBA4404 (Hoekema et al., 1983) using the freeze/thaw method (An et al., 1988). Maize Kn1 cDNA was cloned between the 430-bp CaMV 35S promoter and nopaline synthase termination sequences, as described previously (Sinha et al., 1993), and used in tomato transformations. Tomato cotyledons were transformed and transgenic plants were regenerated as described by Fillatti et al. (1987). 35S-kn1 tomato transformants utilizing this construct have also been described previously by Hareven and coworkers (1996). Some of the phenotypes that we observed in the 35S-LeT6 transgenics were also described by Parnis and coworkers (1997). Note, however, that the LeT6 gene was called the Tkn2 gene in that previous study. Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) leaf segments were transformed according to the method of Sinha et al. (1993).

Histology and SEM

Fixed leaf tissue for thin-section examinations (8–10 μm) was processed according to the method of Chen and coworkers (1997). For SEM fresh tissue was fixed overnight in 3% glutaraldehyde in 0.02 m sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2 to 7.4, postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in a graded ascending series of ethanol, and critical point dried with CO2. Samples were mounted on SEM stubs with epoxy and sputter coated with a 25-nm layer of gold. Samples were viewed with a scanning electron microscope (model pSEM 501, Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. Micrographs were taken on Polaroid 55 film directly from the microscope.

RNA and DNA Gel Blots

Fresh tomato leaf tissue was collected and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted as described by Chomczynski and Sacchi (1987). The RNA was further purified using standard ethanol precipitation. RNA samples were resolved on a 1% phosphate glyoxal gel, transferred to Hybond-N+ membranes (Amersham), and hybridized as described previously (Sambrook et al., 1989). Loading of RNA was estimated by hybridization with a labeled Arabidopsis 18S rDNA probe (Pruitt and Meyerowitz, 1986) or a cDNA clone of the tomato plastocyanin gene (kindly provided by Neil Hoffman, Carnegie Institute of Washington, Stanford, CA).

DNA was extracted using the method of Dellaporta and coworkers (1983), with certain modifications (Chen et al., 1997). When necessary, DNA was further purified by phenol/chloroform extraction and reprecipitation. For DNA gel blots, genomic DNA (20 μg) was digested with restriction enzymes in a large volume (400 μL) and then ethanol precipitated before separation on a 0.8% agarose gel.

The LeT6 probe was a PCR fragment containing the entire LeT6 cDNA and was amplified using T3 and T7 primers. Probes were 32P-labeled using a labeling system (Prime-a-Gene, Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Hybridization, washes, and autoradiography for DNA and RNA gel blots were as described previously (Chen et al., 1997). The RNA gel blots were hybridized at approximately 15°C below the Tm, whereas the washes were done at 5°C to 7°C above the calculated Tm (Sambrook et al., 1989).

RNA in Situ Localizations

Slides for RNA in situ hybridization were labeled using 35S-riboprobes (Meyerowitz, 1987) and digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes (Coen et al., 1990) according to previous methods with some modifications. After anti-digoxigenin antibody labeling and washes, slides were left from overnight to 2 d in wash buffer A (Coen et al., 1990) at 4°C before proceeding to the detection steps. Sections were dehydrated through a graded-ethanol series, cleared in Histoclear (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, GA), and mounted in Permount (Fisher Scientific). Hybridization temperatures were at or 8°C below the Tm, whereas washes were at 12°C above the calculated Tm (Sambrook et al., 1989).

RESULTS

Development of the Wild-Type Leaf in Tomato

Tomato has a unipinnate compound leaf, and the presence of an axillary bud demarcates the leaf base from the stem that bears it (Figs. 1A and 2A). A compound leaf has been considered a lateral determinate organ rather than a branched, stem-like organ because axillary buds are only seen in the junction between the petiole and the stem (the axil). The junction between the rachis and the petiolule, for which we suggest the name “pseudoaxil,” does not normally bear axillary buds (Fig. 1A). Certain aspects of development of the wild-type tomato leaf have been described previously by Coleman and Grayson (1976), Dengler (1984), and Chandra Shekhar and Sawhney (1990).

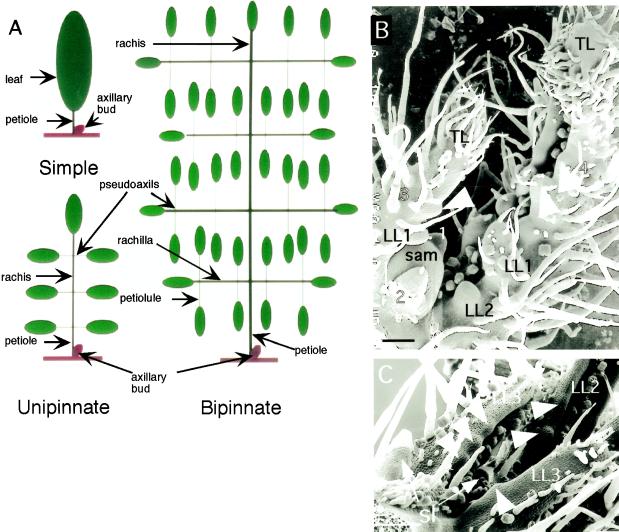

Figure 1.

Wild-type leaf development in tomato. A, Diagram showing the principal features of simple and compound leaves. B, Wild-type SAM with developing leaves. Leaf primordia are marked 1 through 4, from youngest to oldest. Leaflet primordia arise in basipetal succession on leaves 3 and 4. Leaf 4 shows the formation of two pairs of lateral leaflets (LL1 and LL2) in basipetal succession. The terminal leaflet (TL) on leaves 3 and 4 is shown producing lobes (white arrowheads), which occurred in acropetal succession on the terminal leaflet of leaf 4. C, Older wild-type leaf showing two lateral leaflet pairs with lobes (arrows) initiating in a primarily acropetal order. Leaflets are numbered LL2 (oldest) or LL3 (youngest). Leaflet pair 1 and the terminal leaflet are not shown. A smaller minor leaflet (sl) is seen to be arising at the base of the leaf, and another one can be seen between leaflets 2 and 3. Size bars = 100 μm.

In the present study, tomato leaf primordia exhibited a basipetal order of maturation. Leaflets arose as bumps on the adaxial marginal face of the leaf primordium in a basipetal sequence (Fig. 1B). After the upper pair of major lateral leaflet primordia was initiated, the middle pair arose below it. A pair of bumps arose on the terminal leaflet, representing the basal lobes. Smaller minor lateral leaflets (Fig. 1C) are produced between the three large leaflet pairs in a nonbasipetal sequence (Coleman and Grayson, 1976; Dengler, 1984). Our results indicate that individual leaflets show a largely acropetal gradient of morphogenesis, and that, although younger lobes can often be larger than older lobes, lobes arise in acropetal succession on both the terminal and the lateral leaflets (Fig. 1C). An early marked basipetal gradient delimited the terminal leaflet and produced major lateral leaflet primordia. A later acropetal gradient, perhaps coincident with the gradient of early vascular differentiation in the leaf (Coleman and Grayson, 1976), led to the production of marginal lobes on the leaflets. Therefore, the wild-type tomato leaf exhibits several developmental gradients that are not unidirectional.

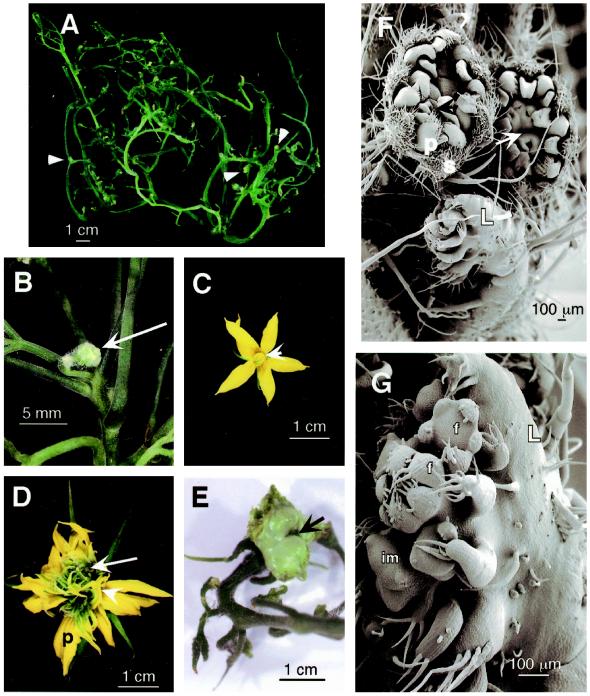

Transgenic Plant Production and Phenotypic Analysis

A total of 27 independent tomato transformants for the 35S-kn1 construct (Fig. 2B) and 23 for the 35S-LeT6 construct were analyzed (Fig. 2, C–H; Table I). The 35S-LeT6 transformed tobacco plants generated resembled those transformed with 35S-kn1 (Sinha et al., 1993), and our 35S-kn1-transformed tomato plants resembled those described by Hareven and coworkers (1996; Fig. 2B). However, the 35S-LeT6 transgenic tomato plants exhibited many phenotypic differences from the 35S-kn1 tomato plants. Often, multiple plants were generated from each callus, and these were given an alphabetical designation within the number (Table I); therefore, “1a” and “1b” represent two individual plants regenerated from callus no. 1. We monitored the phenotype of plants that arose from the same callus (“clonal plants”) and, presumably, from the same transformation event. This presumption was confirmed for most of the plants by DNA gel-blot analysis using a probe specific to the NptII gene to determine the number of Kan loci in the plant (Table I). We saw one instance of two independent transformation events from a “single” callus (Table I; compare 9c with 9a and 9b).

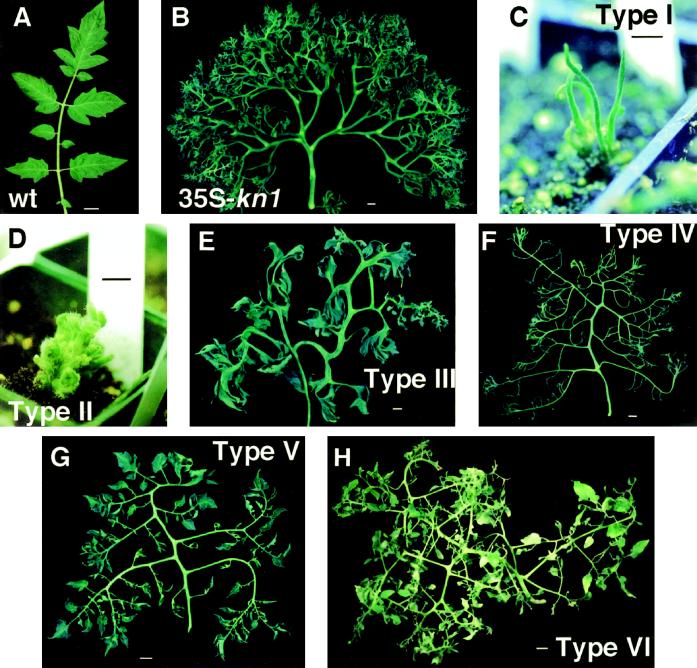

Figure 2.

Comparison of 35S-kn1 and 35S-LeT6 phenotypes in tomato. A, Wild-type tomato leaf showing a terminal leaflet and two pairs of major lateral leaflets. These leaflets are all lobed. In addition, smaller leaflets are seen between the major leaflets. B, A typical 35S-kn1 tomato leaf showing excessive orders of pinnation. C to H, Phenotypes produced by 35S-LeT6 plants. C, Type I plant showing leaf-like structures with no expanded blade. D, Type II plant showing excessive branching and proliferation of floral meristems. E, Type III leaf showing the staghorn-fern-like shape. F, Type IV leaf showing no expanded leaf blades. G, Type V leaf showing expanded blades on leaf segments. H, Type VI leaf showing multiple phenotypes on a single leaf. Size bars = 1 cm.

Table I.

Categories of 35S-LeT6 tomato transformants

| Late Phenotype | Transformant | Early Phenotype | Ectopic Meristems | Copy No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I (Bladeless, simple) | 1a, 1b | NAa | +b | NDc |

| 3a | NA | + | ND | |

| 4a | NA | + | ND | |

| 7a | NA | + | ND | |

| 13a | NA | + | ND | |

| 14a | NA | + | ND | |

| Type II (Branched floral) | 1b | NA | + | ND |

| 2a, 2b | NA | + | ND | |

| 13b | NA | + | ND | |

| 22a, 22a | NA | + | ND | |

| 32a | NA | + | ND | |

| 42a, 42b | NA | + | ND | |

| Type III (Staghorn leaf) | 13b | Staghorn | –e | 4 |

| 25a | *d | – | 1 | |

| Type IV (Bladeless, compound) | 4b | * | – | 4–5 |

| 11b | * | – | 1 | |

| 14b | * | – | 2–3 | |

| 16a | Staghorn | – | 2 | |

| 19a | Staghorn | – | 4 | |

| 21a | Same | + | 1 | |

| Type V (Bladed, compound) | 4c, 4d, 4e | Same | – | 4–5 |

| 6a, 6b | Same | – | 2 | |

| 10a | * | – | 1 | |

| 11a | Staghorn | – | 1 | |

| 12a | Bladeless compound | – | ND | |

| 23a, 23b | Same | – | ND | |

| 24a | Same | – | ND | |

| 9a, 9b | * | – | 1f | |

| Type VI (Multiple leaf types) | 2c | Bladeless compound | + | 2 |

| 9c | Bladed compound | – | 3f | |

| 12b | Bladed compound | – | 1 | |

| 31a | * | – | 1 | |

| 26a | Bladed compound | + | 3 |

Copy number was determined by DNA gel-blot analysis of HindIII-digested DNA probed with the NptII probe.

NA, Not applicable because plants did not survive transplantation.

+, Present.

ND, Not determined.

*, Early phenotype not determined.

–, Not present.

Nonclonal plants from “one” callus.

Our 35S-LeT6 transgenic tomato plants fell into six phenotypic categories (Table I; Fig. 2, C–H) that differed from wild type (Fig. 2A): Type I, plants that produced simple leaves without any blade expansion whatsoever (Fig. 2C); Type II, plants that produced excessively branched axes that terminated in floral structures (Fig. 2D); Type III, staghorn-fern-like leaves with little demarcation between blade and rachis (Fig. 2E); Type IV, compound leaves with no blade expansion (Fig. 2F); Type V, bladed compound leaves (Fig. 2G); and Type VI, variable leaf phenotypes on an individual plant (Fig. 2H). A total of 33 plants represented 23 independent transformation events (Table I). This was based on each primary callus being considered one event (with the exception of callus no. 9). We noticed that clonal plants exhibited enough differences in phenotype to be placed in different categories and often showed different phenotypes during development.

Based on the early and late phenotypic scores (as listed in Table I) the bladed compound leaf category (Type V) was the most stable and had the highest number of independent transformation events. The mature leaves of these plants showed a high degree of compounding, rounded leaflet bases, approximately palmate venation, and multiple leaflet primordia on the rachis. In these aspects the leaves resembled most closely leaves seen in a dominant leaf mutation in tomato called Mouse ears (Me). Me plants have leaves with 2 to 3 orders of compounding, rounded leaflet bases, and palmate venation. We have shown that this mutation is caused by the ectopic overexpression of a fusion between LeT6 and the pyrophosphate-dependent phosphofructokinase gene (Chen et al., 1997). Similar phenotypes to the Type V described here have been reported in another study (Parnis et al., 1997). The first two phenotypic categories (Types I and II) did not survive transplantation. However, we were able to analyze RNA, DNA, and tissue samples from a few representative individuals.

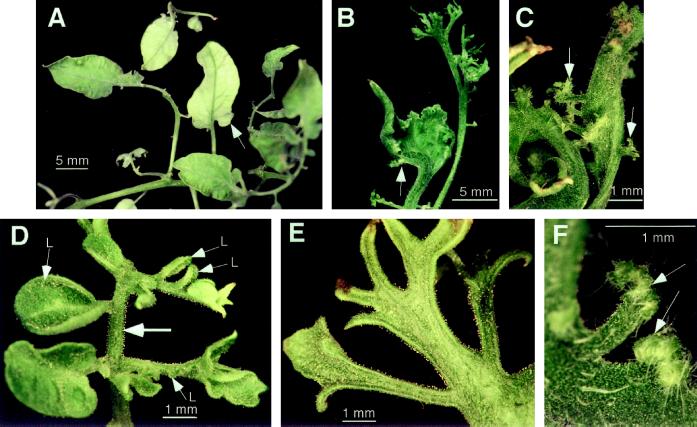

The complete range of variability between the individual transgenic plants (Types I–V) could be seen within some of the multiple-phenotype plants in Type VI. Segments from one leaf on such a multiple-phenotype plant (26a) are shown in Figure 3. Portions of leaves on plant 26a developed relatively normal, unlobed leaflets with pinnate venation (Fig. 3A). Some of the leaflets developed a fasciated rachis and produced leaf-like primordia from the edges of the leaflets and rachis (Fig. 3, B and C; this phenotype was also described by Parnis and coworkers [1997]). Portions of the leaf showed a marked difference in complexity between the pairs of leaflets arising on opposite sides of a rachis (Fig. 3D). Staghorn-fern-like leaves with no distinction between petiolule and leaflet were often seen as well (Fig. 3E). Segments bearing leaflets often showed a fiddlehead-fern-like structure, with immature regions of the leaf segment at the tip (Figs. 3F and 6C). Gel-blot analysis of DNA from four phenotypically distinct portions of plant 26a confirmed that all regions of this plant contained the same T-DNA (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Details of leaf phenotypes seen on a single multiple-phenotype leaf. A, Bladed compound part showing leaflets with very reduced marginal lobes (arrow). B, The margin of a leaflet producing leaflet primordia (arrow). C, Close-up of leaflet in B showing foliar primordia arising at the edge of the blade (arrows). D, Terminal segment showing leaflets (L) developing on one side of the rachilla, whereas on the other side segments are undergoing further orders of leaflet production. E, Staghorn-fern-like segment on the leaf with no distinction between blade and rachis. F, Pinnate segments arising in a coiled manner from the edge of the rachis (arrows).

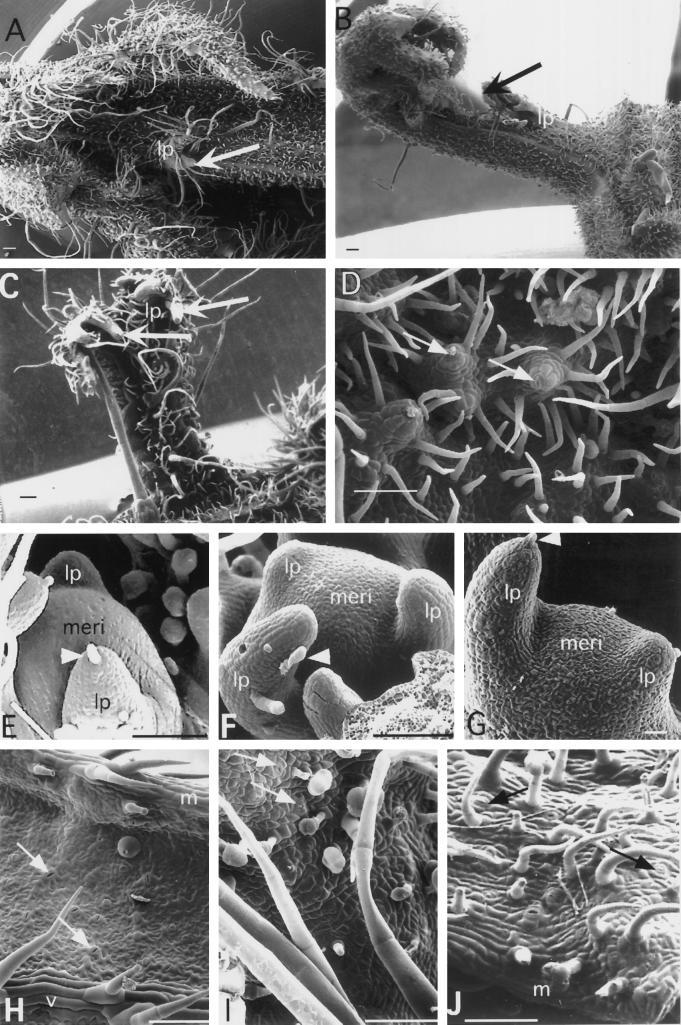

Figure 6.

SEM of 35S-LeT6 phenotypes in tomato. A, Bladed compound leaf with a leaflet primordium (lp; arrow) developing from the mature region of the rachis. B, Compounded leaf structure arising from a pseudoaxil. The first-order branch on the left shows acropetal differentiation; the tip is still immature and has smaller cells. The compounded structure arising from the pseudoaxil also has an acropetal differentiation of segments. C, Fiddlehead-fern-like structure with delayed differentiation at the tip (arrows). D, Stomata on raised columns of cells (arrows) on the adaxial leaf surface. E, Wild-type SAM (meri) producing leaf primordia in succession. A differentiating trichome is seen at the tip of the plastochron 2 leaf (arrowhead). F and G, Meristems on 35S-LeT6 plants producing leaf primordia in succession. The leaf primordium in F does not show basipetal differentiation, whereas the leaf primordium in G does. Differentiating trichomes are marked (arrowheads). H, Leaf blade of wild type showing elongated cells in the leaf margin (m) and over the vasculature (v). Arrows point to stomata on the blade. I, Leaf blade of a 35S-Kn plant showing small epidermal cells with angular margins. Arrows point to stomata on the blade. J, Leaf blade of a 35S-LeT6 plant showing elongated cells in the margin and blade regions. Arrows point to the stomata interspersed between these cells. Scale bars = 100 μm (except in G, which is 15 μm).

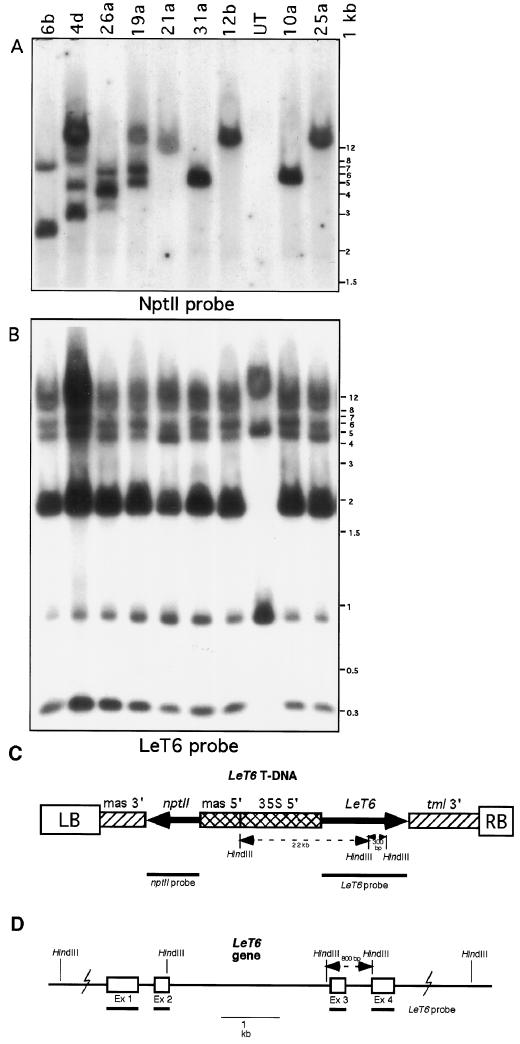

In addition to kanamycin resistance, DNA gel-blot analysis was used to confirm the presence and copy number of the transgene in the plants we analyzed (Fig. 4). Digestion of genomic DNA with HindIII was used to estimate copy number by hybridization with the NptII probe, and the results were confirmed by stripping and rehybridizing the blots with an LeT6 probe (Fig. 4B). Using this probe the intensity of the T-DNA-specific 0.3-kb band (Fig. 4C) could be compared with the intensity of the endogenous 0.8-kb LeT6 band (Fig. 4D) to give an estimate of copy number. One to five copies of the T-DNA were present in the 20 plants examined, and there was no consistent correlation between phenotypic stability or severity and locus copy number (Table I; Fig. 4, A and B). We reasoned that the unstable phenotypes could be the result of cosuppression phenomena or of regeneration of chimeric plants.

Figure 4.

DNA gel-blot analysis of the 35S-LeT6 plants. A, NptII gene used as a probe. NptII-hybridizing bands correspond to the number of integrated copies of T-DNA. B, Same blot as in A stripped and rehybridized with an LeT6 probe. DNA size markers (in kilobases) are on the right. LeT6 probe hybridizes to both the endogenous LeT6 (bands at 800 bp, 5.5 kb, 9 kb, and 11 kb) and the introduced gene (bands at 300 bp and 2.2 kb). The DNA was digested with HindIII and DNA from an untransformed (UT) plant shows only the endogenous bands. A comparison of band intensity differences between the 0.8-kb endogenous and 0.3-kb transgene HindIII fragments correlates with transgene copy number in the transformants. C and D, Map of the transgene locus (C) and the LeT6 locus (D) in tomato. Restriction sites for HindIII are shown.

The analysis of DNA from individual parts of the plants confirmed that plants were not chimeric and that clonal plants derived from the same callus showed identical restriction patterns for the transgene (data not shown). For these plants the phenotypic instability could be the result of variation in tissue- or age-specific transgene expression, or it could be caused by an interaction between the endogenous and introduced LeT6 gene at either the posttranscriptional (Flavell, 1994; Jorgensen, 1995; Que et al., 1997) or the DNA level (Jorgensen, 1995; Matzke and Matzke, 1995; Park et al., 1996).

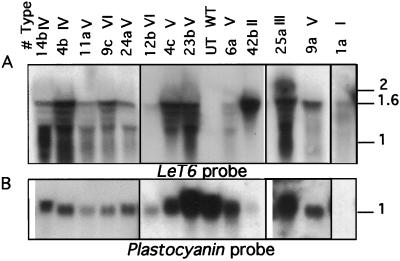

Levels of LeT6 Expression in Leaves of Transformed Tomato Plants

To determine if transgenic phenotypes correlated with levels of transgene expression, we analyzed the expression of LeT6 RNA in mature leaves of our transformants using RNA gel blots. LeT6 transcript is not detected in mature wild-type leaves (Chen et al., 1997; Janssen et al., 1998), but we found LeT6 transcript in leaves from 27 transformed plants (Fig. 5A). Our RNA gel blots showed multiple LeT6-hybridizing bands that did not result from general RNA degradation (plastocyanin [Fig. 5B], 18S rDNA, and LeT12 [not shown] hybridized to single bands of RNA). We used a tomato plastocyanin cDNA as a control probe to determine the levels of RNA loaded on the gel (Fig. 5B). In general, we did not notice any strict correlation between transcript levels and phenotypes or between transcript levels and T-DNA copy number. However, the simple midrib (Type I) and the branched floral (Type II; Fig. 5A, lane 42b) phenotypes showed very high levels of LeT6 RNA. We concluded from our RNA gel-blot analysis that variability in phenotypes between individuals could not simply be attributed to overall levels of LeT6 RNA.

Figure 5.

RNA gel-blot analysis of mature leaf tissue from various 35S-LeT6 transgenic plants. The blots shown in A and B were hybridized first with a PCR-labeled fragment specific to the LeT6 gene (A), then stripped and rehybridized with a tomato plastocyanin probe (B) to determine the amount of RNA loaded. Leaf RNA from an untransformed, wild-type plant (UT WT) does not show any LeT6-hybridizing transcript. The type classification for the individuals used in RNA extraction is indicated at the top of the lanes. The sizes are in kilobases.

Leaf Maturation Is Altered in 35S-LeT6 Leaves

Four of the six phenotypic categories in our transgenic plants produced leaves with many orders of compounding. In one instance we saw 6 orders of pinnation in a leaf. Mature leaflets had very reduced or no marginal lobes (Fig. 3A) and often showed aberrant vasculature, including the absence of a prominent midvein (Fig. 3B). Mature leaves continued to produce leaflet primordia, which often arose either on the leaflet margin or on the rachis (Fig. 3, B–F). SEM analysis revealed that these primordia were regions of immature, undifferentiated cells in an otherwise differentiated region of the leaf (Fig. 6, A–C). This would indicate that even mature 35S-LeT6 leaves retain a potential for organogenesis. The leaflets produced often showed marked coiling like that seen in fern fiddleheads (Figs. 3F and 6, B and C), with a markedly acropetal mode of differentiation and a persistent apical meristematic zone.

Initiating wild-type tomato leaves showed a basipetal maturation gradient (Figs. 1B and 6E). Ectopic expression of LeT6 (and kn1 [Hareven et al., 1996]) in tomato sometimes enhanced the late, acropetal maturation pattern, with the basal region maturing first while the apical (terminal) region remained immature and devoid of trichomes for long periods of time (Figs. 3F, 6B, 6C, and 6F). Such a reversal in leaf maturation is also seen in a naturally occurring gene fusion that causes LeT6 overexpression (Chen et al., 1997). However, meristems bearing leaf primordia with early basipetal differentiation were also seen on 35S-LeT6 plants (Fig. 6G). Meristems in all transgenic plants appeared flattened compared with wild type, regardless of the kind of leaf primordia they had (compare Fig. 6E with 6F and 6G).

The leaves on the 35S-LeT6 plants lacked marginal lobes. When observed under a scanning electron microscope, lobe-like structures were seen to initiate, but these structures matured into leaflets rather than lobes (Figs. 3D and 6B). This suggests that there was no fundamental difference between lobe and leaflet initiation. Delayed differentiation was also seen in cells surrounding the stomata. The last cell divisions in the leaf occur when guard cells are formed in the stomatal complexes (Coleman and Grayson, 1976). In the 35S-LeT6 plants, stomata on the adaxial surface were raised on mounds of cells several layers high (Fig. 6D), presumably as a result of LeT6 expression delaying differentiation and prolonging cell division in the adaxial subepidermal and epidermal layers. Furthermore, cell shapes and arrangements were perturbed in these plants. Wild-type leaves had elongated epidermal cells in the margins and above veins, whereas the region of the blade had large cells shaped like pieces of a puzzle and with interspersed stomata (Fig. 6H). In contrast, 35S-Kn plants had very small cells with angular margins (Fig. 6I). In the 35S-LeT6 transgenics, leaf epidermal cells either resembled the 35S-Kn type (but with stomata raised on mounds; Fig. 6D) or consisted mostly of narrow, elongated cells (Fig. 6J), indicating the presence of a more extended, margin-like domain in these leaves.

Ectopic Meristems Are Initiated on 35S-LeT6 Leaves

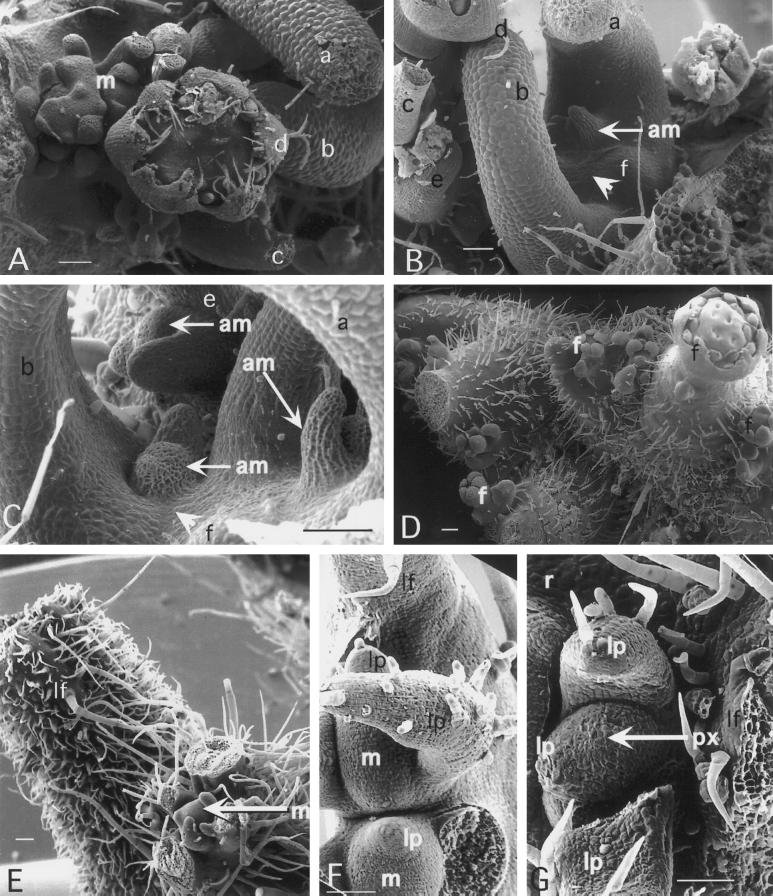

Leaves on 35S-LeT6 plants often produced ectopic meristems. In Type I and Type II plants these meristems were made early in development and often formed floral primordia (Fig. 7, A and D). In Type I plants, the SAM terminated early, and axillary meristems were therefore also precociously activated (Fig. 7, B and C). Leaves on these plants were bladeless and simple, with their normal phyllotactic patterns appearing disrupted prior to SAM termination (Fig. 7C), and ectopic sympodial meristems bearing floral meristems being produced on some leaves (Fig. 7A). Leaves on Type IV and Type VI plants could also produce ectopic meristems on the blade (Fig. 7E) in a manner similar to that described for the 35S-Kn “shooty” phenotype in tobacco (Sinha et al., 1993). Very rarely, leaflet primordia would also bear meristems along their margins. These appeared flattened, as described earlier (Fig. 6, F and G), and produced leaf primordia in succession (Fig. 7F). In addition, a subset of plants produced meristems in the axils of leaflets (pseudoaxils), which sometimes bore leaf primordia (Fig. 7G), but more often produced inflorescence or floral structures (Fig. 8, A and B).

Figure 7.

A through C, Type I plant showing leaves with no blade expansion. A, Shoot apex region showing three radial leaf primordia (a, b, and c) and a floral meristem (d) on the left. Sympodial meristems (m) arise on the adaxial surface of older leaf primordia. B and C, Other views of the same shoot apex as in A showing absence of the SAM at the predicted position (arrowhead). Axillary meristems (am) develop precociously. The corresponding structures have the same identifying letters in A, B, and C. The floral meristem (d) is part of an inflorescence meristem produced from the sympodium (m) on the adaxial face of the leaf primordium. D, Type II phenotype showing clusters of meristems developing into mostly solitary flowers (f). E, Vegetative meristem (arrow) arising from the surface of a leaflet (lf). F, Leaflet (lf) bearing meristems (m) on its margin that are producing leaf primordia (lp). G, Leaflet (lf) bearing a pseudoaxillary meristem (px) at the junction with the rachis (r). The meristem is shown producing leaf primordia. Size bars = 100 μm.

Figure 8.

Reproductive structures in 35S-LeT6 tomato transgenics. A, Leaf with several floral inflorescences (arrowheads) developing in the pseudoaxils. B, An inflorescence with two floral buds (arrow) arising from the pseudoaxil of a leaf. C, Wild-type tomato flower with an outer whorl of green sepals, a whorl of yellow petals, and a column of anthers (arrowhead). D, Fasciated flower with normal sepals, a large number of petals (p), very few stamens (arrowhead), and a cluster of sepaloid organs in the center (arrow). E, Bifurcated fasciated fruit developing from an abnormal flower. Arrow points to a notch in the fruit. F and G, SEM image of a leaflet (L) showing clusters of developing flowers. F, These flowers show the normal order of organ production, with outer sepals (s) and an inner ring of petals (p), but the sizes and numbers are abnormal. A central bifurcation into two units (arrow) is visible in each flower. G, Leaflet showing proliferation of ectopic inflorescence meristems (im) on its surface. These meristems are shown generating floral buds (f).

In Type II plants these leaf-borne meristems were often determined to be inflorescence meristems (Figs. 7D and 8G). Meristems in the later plastochrons of Type IV and Type VI plants were also shown to be inflorescence meristems (Fig. 8, A and B). The inflorescence meristems formed flower primordia that produced floral organs in the normal sequence. However, the flowers were not normal (Fig. 8D), often having larger meristems that produced more organ primordia than normal and that rarely attained full maturity or fertility. Flowers produced in the normal location on these plants also showed similar defects. Alterations in meristem size, fractionation, and organ differentiation, rather than ectopic location, were the likely causes of abnormal flower structures in 35S-LeT6 plants.

On the floral meristems five to six sepal-like structures enclosed a large number of petaloid and green sepaloid organs (Fig. 8D), reminiscent of mutations in C function genes in Arabidopsis (Bowman et al., 1991). Often, the central whorls were bifurcated into two units (Fig. 8, D and F). Upon fertilization, these produced fasciated double or multiple fruit (Fig. 8E) reminiscent of the clavata phenotypes in Arabidopsis (Clark et al., 1993). Thus, overexpression of LeT6 appeared to enhance the phase of SAM proliferation in relation to lateral organ inception so that when organs finally formed, the meristem was able to produce more organs than normal.

Extra organs were produced on the majority of 35S-LeT6 leaves. When these organs were present on the leaflet margins or on the rachis they usually differentiated into leaflets. However, when they were produced at the junction between the petiolule and the rachis (the pseudoaxil), they often resulted in meristems that produced organs (Fig. 8, A and B). There must be an inherent difference between the organogenic potential in the leaflet margin and the rachis compared with the pseudoaxil. The former usually produced determinate, lateral structures (although meristems were seen in rare instances, Fig. 7F), whereas the latter gave rise to indeterminate meristems.

Patterns of LeT6 Expression in Wild-Type and Transgenic Leaves

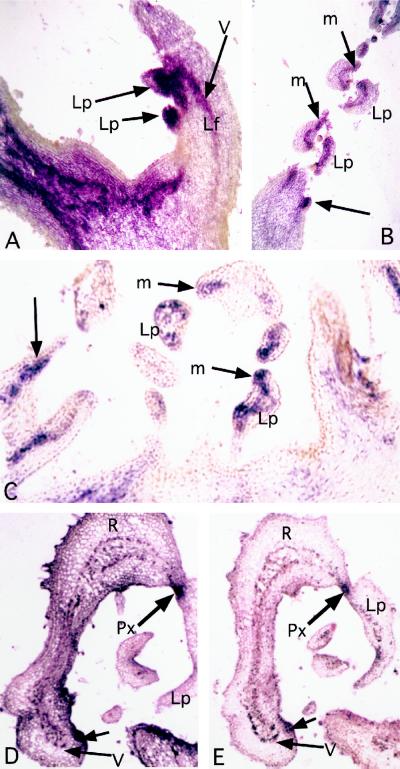

In situ hybridization was used to determine whether LeT6 expression was localized to specific regions of the developing leaves and leaflets in wild-type and 35S-LeT6 plants. LeT6 is expressed in the SAM and initiating leaf primordia (Chen et al., 1997). In older wild-type leaf primordia we saw high LeT6 expression in initiating leaflet primordia (Fig. 9A), indicating that the leaf and leaflet primordium could be equivalent structures. Vascular tissue in leaves and the subtending axis also showed strong expression of LeT6 (Fig. 9A). Expression in the axis vascular tissue has also been seen for kn1 (Smith et al., 1992; Jackson et al., 1994) and Knat1 (Lincoln et al., 1994; Chuck et al., 1996). In addition, the developing leaflet margin showed high levels of LeT6 expression (Fig. 9B), a feature not seen in simple-leaved plants. Analysis of the transgenic leaves revealed high levels of expression in vascular tissue in the marginal blastozone regions (Hagemann and Gleissberg, 1996) (Fig. 9C), and in the junctions between the rachis and petiolule, the pseudoaxils (Fig. 9D).

Figure 9.

Analysis of expression patterns of homeobox genes in wild-type and 35S-LeT6 tomato. A and B, Expression of LeT6 in developing leaves. A, Longitudinal section through a developing leaf primordium (Lf) on the right shows a basipetal order of leaflet production. Each leaflet primordium (Lp) has high levels of LeT6 expression (arrows). Expression is also high in the vascular trace (V) in the leaf. B, Transverse section through an older wild-type leaf shows the basal rachis and three pairs of lateral leaflet primordia. Expression (arrows) is seen in the vascular traces and developing leaflet blade margins (m). The region of high expression on the rachis (arrow) probably represents a site of minor leaflet initiation. C and D, Expression of LeT6 in 35S-LeT6 developing leaves. C, Transverse section through rachis of a multiple-phenotype leaf showing a developing leaflet on the left and a developing compound-leaf-like structure with leaflet primordia in the center. Expression (arrows) is seen in the vascular tissue and in the marginal blastozones (m) from which blades will develop. D, Transverse section through the rachis and leaflet primordia of a multiple-phenotype leaf showing regions of high expression in the pseudoaxils (Px), vascular traces, and edges of the leaf blade (arrow). E, Expression of LeT12 in a tissue section adjacent to that shown in D. Transverse section through the rachis and leaflet primordia of a multiple-phenotype leaf showing regions of high expression in the pseudoaxils, vascular traces, and edges of the leaf blade (arrow).

LeT12 Expression in Transgenic and Wild-Type Leaves

Since animal homeobox genes have been shown to be coordinately regulated (Magli et al., 1991) and also to regulate other homeobox genes (Carroll and Vavra, 1989), we used a class II knox gene, LeT12, as a hybridization probe on RNA gel blots and in situ-hybridization experiments to determine if similar events occur in plant tissues. The LeT12 transcript is 200 bases larger than the LeT6 transcript (1600 bp) and present at moderately high levels in all wild-type tissues we have examined (Janssen et al., 1998). On RNA gel blots we saw a moderate up-regulation of LeT12 levels in transgenic leaves that also showed high levels of LeT6 (data not shown). We used in situ-hybridization experiments to see if the two homeobox genes were expressed in similar regions of the adjacent tissue sections in these leaves. Regions of elevated LeT6 expression also showed elevated LeT12 expression. These were vascular regions in the rachis and blade, pseudoaxillary locations, and leaflet margins (compare Fig. 9, D and E). Our results suggest that in the 35S-LeT6 plants, either LeT6 overexpression led to LeT12 overexpression, or these two genes were coordinately regulated and LeT12 also had a role in morphogenetic events in the tomato leaf.

DISCUSSION

Equivalence of Leaflets and Lobes

The tomato leaf is unipinnately compound, producing a terminal leaflet and usually three pairs of lobed, lateral major leaflets. An early basipetal gradient leads to the production of major leaflet primordia, and a later acropetal gradient leads to the production of marginal lobes and early vascular differentiation. Engineered or natural perturbations in growth and differentiation in this system can interplay with the potential for phenotypic plasticity and lead to complex morphologies.

Leaflet primordia arise from previously undifferentiated basal regions of the leaf and retain the morphogenetic potential to produce lobes, whereas lobe primordia form on regions with reduced morphogenetic potential and quickly form a differentiated blade edge. We hypothesize that leaflets and leaflet lobes are equivalent structures that take on different morphogenetic trajectories by virtue of their position on the leaf (i.e. lobes are prematurely differentiated leaflets). If this is indeed the case, then delaying differentiation in the leaf as a whole should allow initiating lobe primordia to take on a leaflet fate. This seems to be one of the consequences of 35S-LeT6 (and 35S-kn1) overexpression in tomato. These transgenic plants produce leaves with numerous orders of unlobed leaflets. Leaflets beyond the first order (i.e. those produced over and above the “normal” number) are produced in acropetal succession, just as leaflet lobes are, and lobing is usually missing or reduced on these leaves. Furthermore, the initial basipetal gradient indicates that regions closer to the base of the tomato leaf may be the last to differentiate and may retain morphogenetic potential. If this is indeed the case, then one would expect more than just three major ranks of secondary lateral branching in the leaf (the three pairs of leaflets seen in the wild type). This is seen in a number of transformants, indicating that leaflets (or secondary lateral branches) continue to arise from the base of the leaf.

Indeterminate Features in the Tomato Leaf

The compound leaf has sometimes been equated to a structure intermediate between a stem and a leaf (Sattler and Rutishauser, 1992; Lacroix and Sattler, 1994). Although this proposal may have to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, we have analyzed the complex morphologies produced in our 35S-LeT6 plants for similarities to shoot systems. The junction between the rachis and the petiolule on these transgenic leaves often takes on a measure of indeterminacy and shows axillary characteristics. In the more extreme phenotypes, these pseudoaxils produce floral and vegetative meristems, a characteristic feature of leaf axils. In the less-extreme phenotypes, unipinnate or multipinnate, determinate, leaf-like structures are produced from these locations. Incidentally, mutations in tomato that fail to produce axillary meristems often cause the production of ectopic shoots in pseudoaxillary locations on an otherwise normal leaf (Rick and Butler, 1956).

A similar difference in organogenic potential was seen between the sinus region and the rest of the leaf in Arabidopsis plants overexpressing knat1 (Chuck et al., 1996). We have two alternate explanations for these phenotypes. Either these locations have some atavistic axillary features that are enhanced by 35S-LeT6 overexpression or there is some special characteristic in these locations that allows for elevated LeT6 expression, leading to the production of meristems or leaf-like organs. Since the CaMV 35S promoter causes high levels of expression in vascular tissues (Benfey et al., 1989), vascular junctions at these pseudoaxils might have levels of LeT6 above the threshold required for development of shoots.

Phenotypic Variability and Cosuppression

When comparing the results of overexpression of the maize kn1 gene in tomato with overexpression of the endogenous LeT6 gene, the extreme variability of phenotypes observed in the 35S-LeT6 plants stands out. This phenotypic variability is probably the result of several factors acting individually or in combination. Variability of expression from the CaMV 35S promoter and tissue or cell-type specificity of RNA expression may have contributed to these phenotypes. The endogenous gene LeT6 could have unique features that result in phenotypic changes, such as the initiation of meristems at the leaf margins, that are not seen with overexpression of the maize kn1 gene. Phenotypic instability in these transgenic plants may be the result of threshold-dependent cosuppression, a phenomenon dependent on a high level of sequence identity between the transgene and the endogenous gene (de Carvahlo Niebel et al., 1995). Because maize kn1 has only 49% similarity to LeT6 at the nucleotide level, and the Arabidopsis ortholog stm1 is only 65% similar to LeT6, it is unlikely that the 35S-kn1 plants would be able to show such cosuppression of LeT6, Tkn1, or some other knox class I gene. We suggest that endogenous gene effects such as silencing and cosuppression, rather than differences in the constructs, may play a role in the phenotypic effects of LeT6 overexpression in tomato. Distinct roles for the various class I knox genes have also been postulated elsewhere based on transgenic data (Parnis et al., 1997).

Two phenotypic classes of 35S-LeT6 plants are suggestive of cosuppression. The Type I plants show suppression of the SAM and their leaf blades fail to expand. In these plants expression of the endogenous LeT6 gene in the SAM combined with expression of the 35S-LeT6 transgene may result in cosuppression, leading to failure of SAM maintenance. In this respect these plants are strongly reminiscent of the stm mutation in Arabidopsis (Long et al., 1996). The bladeless leaves produced in the Type I plants may result from cosuppression in the edge domain, where both endogenous and 35S-LeT6 gene expression would be expected to be high. Petunia flowers show a similar variation of cosuppression between the edge and internal domains (Que et al., 1997). Type II plants show suppression of the vegetative stage of SAM activity and an almost complete loss of leaf-like structures.

Because expression from the 35S promoter is known to be weak in meristems (H. Klee, personal communication) and higher in differentiating tissues, cosuppression phenomena may be different in these two regions. As the leaf primordium begins to form, 35S-LeT6 expression may increase to a level sufficient to trigger cosuppression, halting cell division and completing differentiation before the leaf primordium can completely form. In these differentiated tissues the endogenous LeT6 expression level would decrease, perhaps below the threshold required for cosuppression, causing induction of a new meristem by overexpression of the 35S-LeT6 transgene. Complete suppression of the vegetative meristem program may cause the plant to shift to the production of floral meristems (Shannon and Meeks-Wagner, 1993).

Coordinate Regulation of Homeobox Genes

Although class I knox genes are expressed at high levels in meristems of Arabidopsis (Lincoln et al., 1994; Long et al., 1996), the class II knox gene Knat 3 has been shown to be expressed at low levels in the SAM and is postulated to have diverse roles in the plant (Serikawa et al., 1997). In contrast, the expression patterns of LeT6, a class I knox gene, and LeT12, a class II knox gene, appear to be very similar in wild-type reproductive structures in tomato (Janssen et al., 1998). This could be due to coincidence, to coordinate regulation of these two genes in the organs examined, or to regulation of expression of one gene by the other. Expression in ectopic locations by the CaMV 35S promoter has allowed us to monitor the expression patterns of LeT12 relative to LeT6 in adjacent tissue sections.

High levels of LeT6 expression are coincident with high levels of LeT12 expression in 35S-LeT6 plants. Either the 35S-LeT6 plants produce ectopic organs and both genes are expressed in these organs (as they would be in wild-type organs of a similar nature) or LeT6 overexpression leads to LeT12 overexpression as part of a developmental cascade of events. This indicates that, as has previously been observed in animal systems (Carroll and Vavra, 1989; Magli et al., 1991), plant homeobox genes may participate in morphogenetic events through an interrelated regulatory network. This may be a way to fine-tune expression patterns and morphogenetic fields. Previous attempts at identifying such regulatory relationships have utilized probes from the class I knox genes only (Jackson et al., 1994). Our results hint that there may be regulation of a class II gene by a class I gene. The nature of this regulation, i.e. direct or indirect, and the consequence of coordinate expression of the two genes in tomato remains to be explored.

Evolutionary Considerations

Compound leaves may have arisen multiple times in the dicots. Leaf morphology seems to be evolutionarily plastic, with variations in degree of pinnation and the order of initiation of leaflets. We see that alterations in levels of a class I knox gene can lead not only to increased orders of pinnation, but can also alter the order in which leaflets are generated. This suggests that some of the natural variation in compound leaf morphology could be explained by alterations in the expression patterns of the class I knox genes. The Type II transgenic class bears resemblance to genera in the aquatic Angiosperm family Podostemaceae, in which most members have “thalloid” bodies that produce clusters of floral branches (Rutishauser, 1995). Analysis of homeobox gene expression in these genera and in organisms with leaves bearing ectopic meristems (e.g. Kalanchoe) may be useful in elucidating the causes of these unique morphologies.

Overexpression of the class I knox gene LeT6 in tomato has revealed an important role for this gene in morphogenesis of the compound leaf. These transgenic leaves produce meristems in ectopic locations analogous to axils between the junction of the leaf and the stem. In addition, gradients of maturation are altered in these leaves, leading to conversion of lobes into leaflets. These features indicate that the tomato leaf has some indeterminate stem-like features, and that leaves, leaflets, and lobes all represent a continuum of structures that are distinguishable only by virtue of timing and maturation patterns of the organ as a whole. The phenotypes that we observed, as well as the changes in determinacy in the transgenic plants, suggest that alterations in homeobox gene expression may provide one explanation for the natural range of variability in leaf shape and plant form.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to John Harada for advice and encouragement, to Rich Jorgensen for helpful discussions on cosuppression, and to Sharon Kessler, Tom Goliber, and Kim Snowden for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Dr. Charlie Rick and the Tomato Genetics Resource Center, University of California, Davis (UCD), for seed stocks, and we are especially grateful to Virginia Ursin and Maureen Daley of Calgene, Inc., for allowing us to perform the tomato transformations at their facility with assistance from Danny Lee, Huy Nguyen, and Joy Philipson. We also thank Andrina Williams for help with the SEM and in situ analyses, and Vivek Pai (National Science Foundation Young Scholars Program at UCD) and Bhaskar Sinha for help with the tobacco transformations.

Abbreviations:

- CaMV

cauliflower mosaic virus

- SAM

shoot apical meristem

- SEM

scanning electron microscopy

Footnotes

This work was funded by the National Science Foundation (grant no. IBN-96-32013).

LITERATURE CITED

- An G, Ebert PR, Mitra A, Ha SB. Binary vectors. In: Gelvin SB, Schilperoort RA, editors. Plant Molecular Biology Manual. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1988. pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Benfey PN, Ren L, Chua N-H. The CaMV 35S enhancer contains at least two domains which can confer different developmental and tissue-specific expression patterns. EMBO J. 1989;8:2195–2202. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08342.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman JL, Smyth DR, Meyerowitz EM. Genetic interactions among floral homeotic genes of Arabidopsis. Development. 1991;112:1–20. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrol SB, Vavra SH. The zygotic control of Drosophila pair-rule gene expression: spacial repression by gap and pair rule gene products. Development. 1989;107:673–683. doi: 10.1242/dev.107.3.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra Shekhar KN, Sawhney VK. Leaf development in the normal and solanifolia mutant of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) Am J Bot. 1990;77:46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Chen J-J, Janssen B-J, Williams A, Sinha N. A gene fusion at a homeobox locus: alterations in leaf shape and implications for morphological evolution. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1289–1304. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.8.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuck G, Lincoln C, Hake S. KNAT1 induces lobed leaves with ectopic meristems when overexpressed in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1277–1289. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.8.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SE, Running MP, Meyerowitz EM. CLAVATA1, a regulator of meristem and flower development in Arabidopsis. Development. 1993;119:397–418. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.2.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen ES, Romero JM, Doyle S, Elliott R, Murphy G, Carpenter R. Floricaula: a homeotic gene required for flower development in Antirrhinum majus. Cell. 1990;63:1311–1322. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90426-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman WK, Greyson RI. The growth and development of the leaf in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) II: leaf ontogeny. Can J Bot. 1976;54:2704–2717. [Google Scholar]

- Comai LC, Moran P, Maslyar D. Novel and useful properties of a chimeric plant promoter combining CaMV 35S and MAS elements. Plant Mol Biol. 1990;15:373–381. doi: 10.1007/BF00019155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Carvahlo Niebel F, Frendo P, van Montagu M, Cornelissen M. Post-transcriptional cosuppression of β-1,3-glucanase genes does not affect accumulation of transgene nuclear mRNA. Plant Cell. 1995;7:347–358. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellaporta SJ, Wood J, Hicks JB. A plant DNA minipreparation, version II. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1983;1:19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Dengler NG. Comparison of leaf development in normal (+/+), entire (e/e), and Lanceolate (La/+) plants of tomato, Lycopersicon esculentum “Ailsa Craig.”. Bot Gaz. 1984;145:66–77. [Google Scholar]

- Eames AJ. Morphology of Angiosperms. Co., New York: McGraw-Hill; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Fillatti JJ, Kiser J, Rose R, Comai L. Efficient transfer of a glyphosate tolerance gene into tomato using a binary Agrobacterium tumefaciens vector. Bio/Technology. 1987;5:726–730. [Google Scholar]

- Flavell RB. Inactivation of gene expression in plants as a consequence of specific sequence duplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3490–3496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann W (1984) Morphological aspects of leaf development in ferns and angiosperms. In RA White, WC Dickison, eds, Contemporary Problems in Plant Anatomy. Academic Press, New York, pp 301–349

- Hagemann W, Gleissberg S. Organogenetic capacity of leaves: the significance of marginal blastozones in angiosperms. Plant Syst Evol. 1996;199:121–152. [Google Scholar]

- Hareven D, Gutfinger T, Parnis A, Eshed Y, Lifschitz E. The making of a compound leaf: genetic manipulation of leaf architecture in tomato. Cell. 1996;84:735–744. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekema A, Hirsch PR, Hooykaas PJJ, Schilperoort RA. A binary vector strategy based on separation of vir- and T-region of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti-plasmid. Nature. 1983;303:179–180. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D, Veit B, Hake S. Expression of maize KNOTTED-1 related homeobox genes predicts patterns of morphogenesis in the vegetative shoot. Development. 1994;120:405–413. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen B-J, Williams A, Chen J-J, Mathern J, Hake S, Sinha N. Isolation and characterization of two knotted-like homeobox genes from tomato. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;36:417–425. doi: 10.1023/a:1005925508579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen RA. Cosuppression, flower color patterns, and metastable gene expression states. Science. 1995;268:686–691. doi: 10.1126/science.268.5211.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstetter R, Vollbrecht E, Lowe B, Veit B, Yamaguchi J, Hake S. Sequence analysis and expression patterns divide the maize knotted1-like homeobox genes into two classes. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1877–1887. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.12.1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix CR, Sattler R. Expression of shoot features in early leaf development of Murraya paniculata (Rutaceae) Can J Bot. 1994;76:678–687. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln C, Long J, Yamaguchi J, Serikawa K, Hake S. A knotted1-like homeobox gene in Arabidopsis is expressed in the vegetative meristem and dramatically alters leaf morphology when overexpressed in transgenic plants. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1859–1876. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.12.1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JA, Moan EI, Medford JI, Barton MK. A member of the KNOTTED class of homeodomain proteins encoded by the STM1 gene of Arabidopsis. Nature. 1996;379:66–69. doi: 10.1038/379066a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magli MC, Barba P, Celetti A, De Vita G, Cillo C, Boncinelli E. Coordinate regulation of HOX genes in human hematopoietic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6348–6352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzke MA, Matzke AJM. How and why do plants inactivate homologous (trans)genes? Plant Physiol. 1995;107:679–685. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.3.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride KE, Summerfelt KR. Improved binary vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Plant Mol Biol. 1990;14:269–276. doi: 10.1007/BF00018567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis W, Levine MS, Hafen E, Kuroiwa A, Gehring WJ. A conserved DNA sequence in homeotic genes of the Drosophila antennapedia and bithorax complexes. Nature. 1984;308:428–433. doi: 10.1038/308428a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill EK. Heteroblastic seedlings of green ash. I. Predictability of leaf form and primordial length. Can J Bot. 1986;64:2645–2649. [Google Scholar]

- Meyerowitz EM. In situ hybridization to RNA in plant tissue. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1987;5:242–250. [Google Scholar]

- Park Y-D, Papp I, Moscone EA, Iglesias VA, Vaucheret H, Matzke AJM, Matzke MA. Gene silencing mediated by promoter homology occurs at the level of transcription and results in meiotically heritable alterations in methylation and gene activity. Plant J. 1996;9:183–194. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1996.09020183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnis A, Cohen O, Gutfinger T, Hareven D, Zamir D, Lifschitz E. The dominant developmental mutants of tomato, Mouse-ear and Curl, are associated with distinct modes of abnormal transcriptional regulation of a Knotted gene. Plant Cell. 1997;9:2143–2158. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.12.2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt RE, Meyerowitz EM. Characterization of the genome of Arabidopsis thaliana. J Mol Biol. 1986;187:169–183. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Que Q, Wang H-Y, English J, Jorgensen RA. The frequency and degree of cosuppression by sense chalcone synthase transgenes are dependent on transgene promoter strength and are reduced by premature nonsense codons in the transgene coding sequence. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1357–1368. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.8.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rick CM, Butler L. Cytogenetics of the tomato. Adv Genet. 1956;7:267–382. [Google Scholar]

- Rutishauser R. Developmental patterns of leaves in Podostemaceae compared with more typical flowering plants: saltational evolution and fuzzy morphology. Can J Bot. 1995;73:1305–1317. [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sattler R, Rutishauser R. Partial homology of pinnate leaves and shoots: orientation of leaflet inception. Bot Jahrb Syst Pflanzengesch pflanzengeogr. 1992;114:61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Scott MP, Tamkun JW, Hartzell GW., III The structure and function of the homeodomain. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;989:25–48. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(89)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serikawa K, Martinez-Laborda A, Kim H-S, Zambryski P. Localization of expression of KNAT3, a class 2 knotted1-like gene. Plant J. 1997;11:853–861. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.11040853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon S, Ry Meeks-Wagner D. Genetic interactions that regulate inflorescence development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1993;5:639–655. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.6.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha N, Williams R, Hake S. Overexpression of the maize homeobox gene, KNOTTED-1, causes a switch from determinate to indeterminate cell fates. Genes Dev. 1993;7:787–795. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.5.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha N. Simple and compound leaves: reduction or multiplication? Trends Plant Sci. 1997;2:396–402. [Google Scholar]

- Smith LG, Greene B, Veit B, Hake S. A dominant mutation in the maize homeobox gene, Kn1, causes its ectopic expression in leaf cells with altered fates. Development. 1992;116:21–30. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollbrecht E, Veit B, Sinha N, Hake S. The developmental gene Knotted-1 is a member of a maize homeobox gene family. Nature. 1991;350:241–243. doi: 10.1038/350241a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]