Abstract

Background

Hypermethylation of promotor CpG islands is a common mechanism that inactivates tumor suppressor genes in cancer. Genes belonging to the RASSF gene family have frequently been reported as epigenetically silenced by promotor methylation in human cancers. Two members of this gene family, RASSF1A and RASSF5A have been reported as methylated in neuroblastoma. Data from our previously performed genome-wide DNA methylation array analysis indicated that other members of the RASSF gene family are targeted by DNA methylation in neuroblastoma.

Results

In the current study, we found that several of the RASSF family genes (RASSF2, RASSF4, RASSF5, RASSF6, RASSF7, and RASSF10) to various degrees were methylated in neuroblastoma cell lines and primary tumors. In addition, several of the RASSF family genes showed low or absent mRNA expression in neuroblastoma cell lines. RASSF5 and RASSF6 were to various degrees methylated in a large portion of neuroblastoma tumors and RASSF7 was heavily methylated in most tumors. Further, CpG methylation sites in the CpG islands of some RASSF family members could be used to significantly discriminate between biological subgroups of neuroblastoma tumors. For example, RASSF5 methylation highly correlated to MYCN amplification and INRG stage M. Furthermore, high methylation of RASSF6 was correlated to unfavorable outcome, 1p deletion and MYCN amplification in our tumor material.

In conclusion

This study shows that several genes belonging to the RASSF gene family are methylated in neuroblastoma. The genes RASSF5, RASSF6 and RASSF7 stand out as the most promising candidate genes for further investigations in neuroblastoma.

Introduction

Neuroblastoma (NB) is the most commonly occurring solid extra-cranial tumor in children accounting for 6% of cancer incidence and 9% of cancer deaths in children [1]. It is a highly clinically and biologically heterogeneous cancer of the postganglionic sympathetic nervous system with tumors developing from immature or dedifferentiated neural crest cells [1,2]. Most tumors originate in the adrenal medulla or in paraspinal sympathetic ganglia. Common genetic alterations in NB tumors are MYCN amplification, 17q gain, 1p deletion and loss of 11q [2,3]. The list of genes epigenetically silenced in cancer is growing and the inactivated genes represent all cellular pathways. Several genes have been reported as silenced by methylation in NB and one example is the Ras-associated family member RASSF1A, located at chromosome 3p [4]. CpG island methylation of RASSF1A has been reported as a frequent event in NB tumors and cell lines [4] and loss of heterozygozity (LOH) at 3p, i.e. the loci containing the RASSF1A gene, has been reported in primary NB tumors [5]. RASSF1A is also epigenetically silenced by promoter methylation in many other human tumors [6]. The Ras proto-oncogenes belong to a super-family of GTPases that participate in a range of cellular processes such as cell growth, adhesion, migration, differentiation and apoptosis [7], with defects in Ras signaling pathway resulting in disease and oncogenesis. The Ras proteins carry out their diverse functions via interaction with RASS effectors which have conserved Ras interacting domains. One of many such Ras interacting domains is the RA-domain, and the RA-domain is a common feature of the genes in the Ras-association domain family (RASSF). This family has ten members; RASSF1-10, which are divided into two groups, the classical members RASSF1-6 and the N-terminal members RASSF7-10[8]. The classical RASSF family members have been reported to be involved in many biological processes such as microtubule stability, cell cycle control and apoptosis and are generally considered as tumor suppressors [8]. Based on our previous data using IIumina 27K methylation arrays [9] we noted that several of the RASSF genes were methylated in NB. Eight of the RASSF genes were included on the IIumina 27K methylation arrays (RASSF1A, RASSF2, RASSF3, RASSF4, RASSF5, RASSF6, RASSF7 and RASSF8). The following seven RASSF genes were chosen for further methylation analysis; RASSF2, RASSF4, RASSF5, RASSF6, RASSF7, RASSF8 and RASSF10). The two CpG sites in RASSF3 were unmethylated in all NB tumors and this gene was therefore not investigated further. RASSF8 however, we wanted to include in the verification analysis with BSP to see if surrounding CpG sites also were unmethylated since this gene has been reported as methylated in Childhood Leukemia cell lines [10]. RASSF1A was not analyzed further as this gene is well known to be deregulated in NB due to DNA methylation. Recent published data have shown that RASSF10 is methylated in other cancers which led us to include this gene in our analyses. In addition to the RASSF1A gene, DNA methylation was found in six out of seven analyzed RASSF genes (RASSF2, 4, 5–7 and 10). Several of the RASSF genes had reduced mRNA expression levels in NB cell lines and the methylation status of some of the RASSF genes was able to significantly discriminate between biological subgroups of NB tumors.

Material and methods

Cell lines and tumor material

A panel of nine NB cell lines; Kelly, NB69, SK-N-SH, SH-SY-5Y, SK-N-AS, SK-N-BE(2), SK-N-DZ, SK-N-FI and IMR-32 were used for analysis of DNA methylation status. All nine NB cell lines were subjected to epigenetic drug treatment and expression analysis with end-point RT-PCR or qRT-PCR. In addition, we have previously generated cDNA microarray data for SK-N-AS, SK-N-BE(2), SK-N-DZ and IMR-32 [9]. Data from Illumina Human Methylation27K DNA analysis BeadChips from fifty-nine primary NB tumors (Table 1) were also used, together with four NB cell lines, SK-N-AS, SK-N-BE(2), SK-N-DZ and IMR-32, one adrenal sample, unmethylated and methylated controls (EpiTect control DNA, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) [9]. Control for the genomic content and the authenticy of all cell lines have been performed and genomic profiles of the cell lines generated [11]. Furthermore, short tandem repeat fingerprinting/genotyping of all the cell lines used were performed to verify the identity of cell lines, as described earlier [11].

Table 1.

Patient data

| Tumor id | Outcome | INRG | age at diagnosis | age at follow up | 1p-del | MNA | 11q-del | 17q-gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10E6 |

NED |

M |

<18 m |

>60 m |

pos |

pos |

neg |

pos |

| 10E7 |

DOD |

M |

>18 m |

<60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

pos |

| 10R2 |

DOD |

M |

<18 m |

<60 m |

pos |

pos |

neg |

pos |

| 10R4 |

NED |

MS |

<18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

| 10R8 |

DOD |

L |

>18 m |

<60 m |

neg |

neg |

pos |

neg |

| 11E1 |

NED |

M |

>18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

neg |

pos |

pos |

| 11E8 |

NED |

L |

<18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

| 11R9 |

DOD |

M |

>18 m |

<60 m |

neg |

neg |

pos |

pos |

| 12E5 |

NED |

MS |

<18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

| 12R1 |

NED |

M |

<18 m |

>60 m |

pos |

neg |

neg |

pos |

| 12R6 |

DOD |

M |

>18 m |

<60 m |

pos |

pos |

neg |

neg |

| 12R9 |

NED |

M |

>18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

pos |

neg |

neg |

| 13R0 |

DOD |

M |

>18 m |

<60 m |

neg |

pos |

pos |

pos? |

| 13R1 |

DOD |

L |

>18 m |

<60 m |

neg |

pos |

pos |

pos |

| 15R8 |

NED |

L |

<18 m |

>60 m |

pos |

neg |

pos |

pos |

| 16E2 |

NED |

L |

<18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

| 16E9 |

DOD |

M |

>18 m |

<60 m |

neg |

pos |

neg |

pos? |

| 16R4 |

NED |

L |

>18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

pos |

neg |

pos |

| 17E2 |

NED |

L |

>18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

| 17E4 |

DOD |

M |

>18 m |

<60 m |

neg |

pos |

pos |

pos |

| 18E2 |

NED |

L |

>18 m |

>60 m |

pos |

neg |

neg |

pos |

| 18E4 |

DOD |

M |

<18 m |

<60 m |

neg |

pos |

pos |

pos |

| 18E5 |

NED |

L |

>18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

| 18E7 |

NED |

L |

>18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

pos |

| 18E8 |

NED |

L |

<18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

| 19R1 |

NED |

L |

>18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

| 19R6 |

DOD |

L |

<18 m |

<60 m |

neg |

pos |

pos |

pos |

| 20R8 |

NED |

L |

>18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

pos |

pos |

pos |

| 23R2 |

NED |

L |

>18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

pos |

|

|

| 23R4 |

NED |

L |

<18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

| 25R6 |

DOD |

M |

>18 m |

<60 m |

neg |

pos |

pos |

pos |

| 25R7 |

NED |

L |

<18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

| 26R0 |

NED |

M |

>18 m |

>60 m |

pos |

neg |

pos |

pos |

| 26R1 |

NED |

L |

<18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

| 27R7 |

NED |

L |

<18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

| 28R2 |

NED |

|

<18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

pos |

pos |

pos |

| 30R0 |

NED |

M |

>18 m |

>60 m |

pos |

neg |

neg |

neg |

| 32R2 |

NED |

M |

>18 m |

>60 m |

pos |

neg |

pos |

pos |

| 34R0 |

DOD |

M |

>18 m |

<60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

pos |

| 34R5 |

NED |

L |

<18 m |

<60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

| 35R5 |

NED |

L |

<18 m |

<60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

| 35R7 |

DOD |

M |

<18 m |

<60 m |

pos |

neg |

neg |

neg |

| 36R1 |

DOD |

M |

>18 m |

<60 m |

pos |

neg |

neg |

pos |

| 36R2 |

NED |

M |

>18 m |

<60 m |

pos |

neg |

neg |

pos |

| 36R3 |

DOD |

MS |

<18 m |

<60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

pos |

| 37R5 |

NED |

L |

<18 m |

<60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

| 37R6 |

NED |

L |

<18 m |

<60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

| 38R6 |

NED |

L |

>18 m |

<60 m |

neg |

neg |

pos |

neg |

| 39R1 |

NED |

M |

>18 m |

<60 m |

neg |

pos |

pos |

pos |

| 3E2 |

DOD |

M |

>18 m |

<60 m |

pos |

neg |

neg |

pos |

| 43R2 |

DOD |

M |

<18 m |

<60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

pos |

| 43R3 |

NED |

M |

>18 m |

<60 m |

neg |

pos |

pos |

pos |

| 4E1 |

DOD |

M |

>18 m |

<60 m |

pos |

neg |

neg |

pos |

| 5E1 |

NED |

L |

<18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

| 6E9 |

DOD |

L |

>18 m |

<60 m |

pos |

neg |

pos |

pos |

| 8E4 |

NED |

L |

<18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

| 8E7 |

NED |

L |

>18 m |

>60 m |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

| 9E5 |

DOD |

M |

>18 m |

<60 m |

neg |

pos |

pos |

pos |

| 9R9 | DOD | M | >18 m | <60 m | pos | neg | pos | pos |

NED, no evidence of disease; DOD, dead of disease; L, localized; M, metastatic; m, months.

1p-del, 1p-deletion; MNA, MYCN amplification; 11q-del, 11q-deletion; neg, negative; pos, positive.

Analysis of DNA methylation

1 μg of genomic DNA was bisulfite modified using the EpiTect kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Methylation status of seven RASSF family genes was investigated using bisulfite sequencing, methylation-specific PCR (MSP) or combined bisulfite restriction analysis (COBRA).

Methylation-specific PCR (MSP) and bisulfite sequencing

PCR amplifications were performed according to Carén et al. [9]. Primers were designed with the Bisearch software [12] and are listed in Table 2. One fully methylated control sample, one unmethylated control sample and one 50/50 mixture of methylated and unmethylated control (EpiTect) were used to optimize the reaction conditions and to ensure that the bisulfite modified DNA samples were equally amplified despite their methylation status. PCR products were visualized on a 2% agarose gel with GelRed (Biotinum, Hayward, CA). The methylation status of RASSF2A was determined using MSP and the methylation status of RASSF5, RASSF7, RASSF8 and RASSF10 were analyzed with bisulfite sequencing [9].

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Gene | Method | Primer sequence | Product (bp) | AT °C | Primer design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

RASSF2A |

MSP |

F: 5′-GTTCGTCGTCGTTTTTTAGGCG-3′ |

109 |

62 |

[13] |

| |

|

R: 5′-AAAAACCAACGACCCCCGCG-3′ |

|

|

|

|

RASSF2A |

MSP |

F: 5′-AGTTTGTTGTTGTTTTTTAGGTGG-3′ |

109 |

60 |

[13] |

| |

|

R: 5′-AAAAAACCAACAACCCCCACA-3′ |

|

|

|

|

RASSF4 |

COBRA |

F: 5′-AGGATAYGATATATGTAGTGGTTTTTGGATT-3′ |

270 |

TD 65-55 |

[14] |

| |

|

R: 5′-ATTATAACCCCTAAATTACTTAACAAAAATACCAAA-3′ |

|

|

|

|

RASSF5A* |

BSP |

F: 5′-TTAGGAAAGAGGAATATTTTAT-3′ |

434 |

TD 60-50 |

[12] |

| |

|

R: 5′-TAAACCTTCAACCCTACCTCTTTC-3′ |

|

|

|

|

RASSF5C** |

BSP |

F: 5′-GGGGTTTAGAGTTAGGGGTTTA-3′ |

345 |

TD 60-50 |

[12] |

| |

|

R: 5′-TATAACTTTATCCCTTTACTA-3′ |

|

|

|

|

RASSF6 |

COBRA |

F: 5′-GTATAGGGAGTGGTTTAGGTTTTTTGATAT-3′ |

353 |

TD 67-57 |

[10] |

| |

|

R: 5′-ATCCCCATTTTTTACCTATTATTCACACTATA-3′ |

|

|

|

|

RASSF7 |

BSP |

F: 5′-GAGAAAAGTTAGGTTTTAGA-3′ |

592 |

TD 62-52 |

[12] |

| |

|

R: 5′-CTCAACAACCTTCTAATATAA-3′ |

|

|

|

|

RASSF8 |

BSP |

F: 5′-TTTTATAATGTAGYGTTGGYGTTTTAGTTT-3′ |

374 |

TD 67-57 |

[10] |

| |

|

R: 5′-CRAAACTCRACRAAACTAAACRAAAAACT-3′ |

|

|

|

|

RASSF10 |

BSP |

F: 5′-TTGTTTTTGTTGTTTTYGTYGTTTTAGTAGATT-3′ |

634 |

TD 67-57 |

[10] |

| |

|

R: 5′-CRATTAAACTTAACCAATTTACRAAAAACCTTA-3′ |

|

|

|

|

RASSF2A |

qRT-PCR |

F: 5′-AAGGGGTGGAGAGTGATATGAAGAG-3′ |

194 |

60 |

[15] |

| |

|

R: 5′-AGGGACGTTTGGTGGCTGTAGT-3′ |

|

|

|

|

RASSF4 |

qRT-PCR |

F: 5′-GGACTGCGCGATGACTGGAC-3′ |

126 |

56 |

[15] |

| |

|

R: 5′-CCGACTTCTGAATGGACTTGCTGT-3′ |

|

|

|

|

RASSF5 |

End-point RT-PCR |

F: 5′-CCTGGGCATGAAACTGAGTGAAGA-3′ |

188 |

56 |

Manual |

| |

|

R: 5′-tgatggcatctaggggcaggtaga-3′ |

|

|

|

|

RASSF6 |

End-point RT-PCR |

F: 5′-ATGGAGAGACTGAAGATGGC-3′ |

203 |

56 |

[15] |

| |

|

R: 5′-CAGGGTGTTGCTGTGATAAG-3′ |

|

|

|

|

RASSF7 |

End-point RT-PCR |

F: 5′-CAGCAGAGCGAGCCTTGCAGGCTCA-3′ |

149 |

59 |

Manual |

| |

|

R: 5′-CTGAGTGCCAGGAGGGCCCCTGTCA-3′ |

|

|

|

|

RASSF10 |

qRT-PCR |

F: 5′-CCATGACCCAGGAGAAACAG-3′ |

226 |

60 |

[10] |

| R: 5′-TGCTGGCGAATTGTGTGGTC-3′ |

*cg17558126, **cg02589695.

MSP, Methylation specific PCR; BSP, Bisulfite sequencing PCR; COBRA, Combined bisulfite restriction PCR.

qRT-PCR, Quantitative real time PCR; AT, Annealing temperature; TD, Touch down.

Combined bisulfite restriction analysis (COBRA)

The methylation status of RASSF4 and RASSF6 was determined using COBRA [16]. Bisulfite modified DNA was amplified as described above (primers in Table 2). For RASSF4, 2 μl of PCR product was incubated with 2U BstUI enzyme (CGCG) and 1xNEBuffer4 (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) for 2 hours at 60°C. For RASSF6, 2 μl of PCR product was incubated with 1U of FastDigest TaqI (TCGA) and 1X FastDigest Green Buffer (Fermentas, Germany) for 15 minutes at 65°C. Digestion patterns were visualized on a 2% agarose gel with GelRed (Biotinum).

Epigenetic drug treatments and expression analysis

Changes in gene expression following treatment with the demethylating agent, 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-Aza-dC; Sigma-Aldrich co, St Louis, MO) or/and the histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA; Sigma-Aldrich) were analyzed with either end-point RT-PCR or qRT-PCR using Sybergreen (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis were done as previously described [9]. End-point RT-PCR was used for RASSF5, RASSF6 and RASSF7. PCR reactions were denatured at 96°C for 10 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 96°C for 30 seconds, annealing temperature (Table 2) for 30 seconds and 72°C for 30 seconds ending with a 7 minute extension step at 72°C. PCR products were taken at different time points (cycle 25, 30 and 35) to ensure the detection of the amplification product in the exponential phase. The housekeeping gene GUSB was included as an endogenous control. The end-point RT-PCR products were run on a 2% agarose gel and fragments were visualized with UV-light using GelRed (Biotinum). Quantitation of end-point RT-PCR was performed with ImageJ 1.45 software (NIH, Bethesta, MO) and normalization was done using GUSB. For the genes RASSF2A, RASSF4 and RASSF10, expression analysis was performed with qRT-PCR using Sybergreen (Applied Biosystems) and the SDS software was used to extract Ct-values. Quantification was performed with the standard curve method [17]. GUSB was used for normalization.

Statistical analysis

The methylation beta-values from the CpG sites where methylation of the RASSF genes were detected were extracted from the 27K methylation arrays [9] and the difference in beta-values (methylation frequency) between different biological subgroups of NB were compared with Student’s two-sided t-test. The tests included INRG stage, 5-year overall survival (5-OS), MYCN amplification status, 1p deletion, and 11q deletion. Correction for multiple testing was done with Bonferroni correction. The IIumina ID’s of the CpG sites on the 27K methylation array are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptives of the CpG sites from the 27K methylation array

| |

|

|

Methylation frequency (beta-value) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | ILMNIDa | Relation to CGI | Mean | Range |

|

RASSF1 |

cg00777121 |

CGI |

0.69 |

0.13-0.95 |

| |

cg06063729 |

CGI |

0.02 |

0-0.05 |

| |

cg06821120 |

CGI |

0.12 |

0.02-0.64 |

| |

cg06980053 |

CGI |

0.20 |

0.06-0.59 |

| |

cg08047457 |

CGI |

0.75 |

0.05-0.99 |

| |

cg11035216 |

CGI |

0.02 |

0-0.03 |

| |

cg15043975 |

CGI |

0.06 |

0.04-0.11 |

| |

cg21554552 |

CGI |

0.61 |

0.04-0.96 |

| |

cg26357744 |

CGI |

0.01 |

0-0.04 |

|

RASSF2 |

cg16884569 |

CGI |

0.01 |

0-0.03 |

| |

cg19614321 |

CGI shore |

0.06 |

0.01-0.27 |

|

RASSF3 |

cg07915282 |

CGI |

0.02 |

0-0.07 |

| |

cg12157010 |

CGI |

0.01 |

0-0.02 |

|

RASSF4 |

cg13603099 |

CGI shore |

0.01 |

0-0.02 |

| |

cg17324128 |

CGI |

0.10 |

0.04-0.24 |

|

RASSF5 |

cg01860753 |

CGI |

0.18 |

0.04-0.38 |

| |

cg02589695 |

CGI |

0.23 |

0.06-0.51 |

| |

cg08617916 |

CGI |

0.01 |

0-0.02 |

| |

cg10167296 |

CGI |

0.04 |

0.02-0.1 |

| |

cg17558126 |

CGI |

0.13 |

0.03-0.43 |

| |

cg19452316 |

CGI |

0.04 |

0-0.08 |

| |

cg22857604 |

CGI |

0.04 |

0-0.1 |

| |

cg23520347 |

CGI |

0.05 |

0.01-0.09 |

| |

cg24450312 |

CGI |

0.09 |

0.02-0.16 |

|

RASSF6 |

cg03996822 |

CGI shore |

0.39 |

0-0.94 |

| |

cg08647446 |

CGI |

0.12 |

0.05-0.54 |

|

RASSF7 |

cg14896003 |

CGI shore |

0.96 |

0.89-1.0 |

|

RASSF8 |

cg07469792 |

CGI |

0.01 |

0-0.03 |

| cg22946876 | CGI | 0.00 | 0-0.03 |

ILMNID, Illumina ID; CGI, CpG island.

ahttp://www.illumina.com/Documents/products/technotes/technote_cpg_loci_identification.pdf

Results

Methylation analysis with methylation array, bisulfite sequencing, MSP and COBRA

Bisulfite sequencing, MSP and COBRA assays were performed in order to verify that the methylated CpG sites present on the 27K methylation array were indeed methylated and to explore if surrounding CpG sites had the same methylation status. Six of the seven RASSF genes were found to have methylated CpG islands in at least one NB cell line. Our 27K methylation array data showed dense RASSF1A methylation of NB primary tumors and cell lines which were expected since RASSF1A is well-known to be deregulated by DNA methylation in NB.

The RASSF2A MSP results confirmed the 27K methylation array data in that the cell line SK-N-AS showed low level of methylation. RASSF2A DNA methylation was generally not found in primary NB tumors; only a few cases with low grade methylation were detected.

The RASSF4 gene region that was analyzed with COBRA showed very low level of methylation in three cell lines; SK-N-AS, IMR-32 and Kelly. The 27K methylation array showed that RASSF4 are generally not methylated in primary NB tumors even though some tumors had low level of methylation (methylation frequency below 25%).

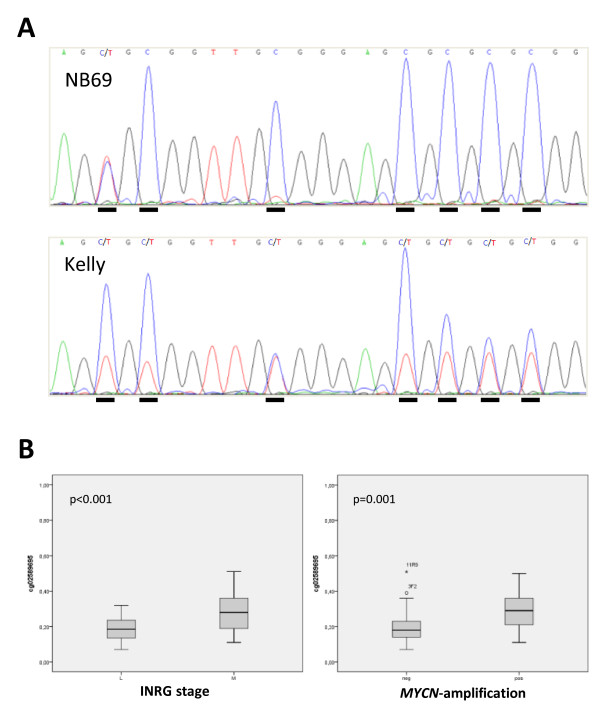

Many of the primary NB tumors showed various levels of RASSF5 methylation of at least one of the CpG sites present on the array, whereas some tumors were unmethylated at all sites present on the array (Table 3). SK-N-AS, IMR-32, SK-N-DZ and SK-N-BE(2) all showed partial methylation of RASSF5 in at least one CpG site on the 27K methylation array. Two bisulfite sequencing assays were designed in order to confirm the RASSF5 27K methylation array results. One assay targeted the CpG rich region upstream of the promoter where the longest RASSF5 transcript (RASSF5A) is initiated. The other targeted a CpG rich region in the promoter where the medium-sized RASSF5 transcript (RASSF5C) is initiated. Bisulfite sequencing showed that the CpG site cg17558126, located just upstream of RASSF5A was methylated in 7/9 NB cell lines and the site cg02589695, located in RASSF5C was methylated in 6/9 NB cell lines. For example the NB cell line NB69 was fully methylated whereas Kelly was partially methylated at the CpG sites in the RASSF5A fragment (Figure 1A). Bisulfite sequencing of RASSF5 thus confirmed the 27K methylation array results for both CpG sites. In NB primary tumors, the methylation frequency (methylation beta-values) of two of the CpG sites on the 27K methylation array were significantly higher in INRG stage M compared to stage L (p-values <0.001, Bonferroni corrected <0.02 for all sites), (Figure 1B). The methylation beta-values were also for two of the sites significantly higher in MYCN-amplified tumors compared to none-amplified (Bonferroni corrected p-values <0.02), (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

RASSF5 methylation and correlation to INRG stage and MYCN amplification. (A) Examples of bisulfite sequencing of RASSF5in the RASSF5A CpG island: top sequence NB69 and bottom sequence Kelly. CpG sites are underlined and C in the sequence indicates methylation and C/T in the sequence indicate partial methylation. (B) High methylation of RASSF5 is significantly correlated to INRG stage M and MYCN amplification. P-values are indicated in the left upper corner in each graph. Box plot explanation; upper and lower hinges of the box represent the 75th percentile and 25th respectively; whiskers show highest and lowest values. Open circles represent outliers and asterisks show extremes.

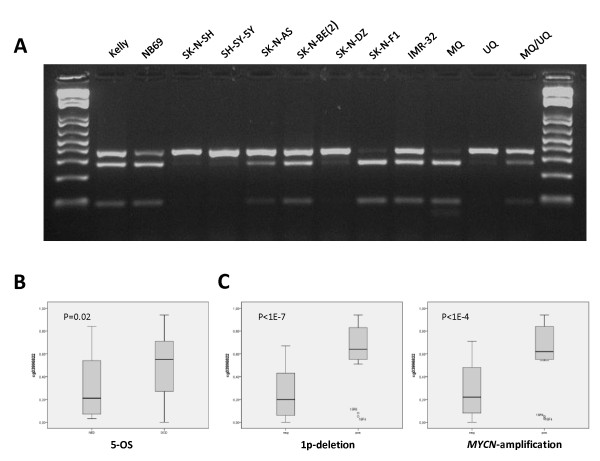

The 27K methylation array showed partial RASSF6 methylation of at least one of the two CpG sites present on the array in all NB cell lines. The analyzed CpG island region of RASSF6 was shown to be methylated in six out of nine (67%) cell lines according to our COBRA results (Figure 2A). The COBRA results thus confirmed partial methylation of RASSF6 in IMR-32 and SK-N-BE(2) as well as the lower level of methylation in SK-N-AS. The methylation beta-values were significantly higher in patients with an unfavorable 5-year overall survival (Bonferroni corrected p-value <0.03), (Figure 2B). A higher methylation was also detected in 1p-deleted and MYCN-amplified tumors, with the most significant site located in the CpG island shore (Bonferroni corrected p-values of <5x10-7 and p < 2x10-4, respectively, Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

RASSF6 methylation and correlation to outcome, 1p deletion and MYCN amplification. (A)Combined bisulfite restriction analysis of RASSF6 .PCR products are cleaved with TaqI. Samples from left to right: Kelly, NB69, SK-N-SH, SH-SY-5Y, SK-N-AS, SK-N-BE(2), SK-N-DZ, SK-N-FI, IMR-32, methylated control (MQ), unmethylated control (UQ) and a 50% mixture of methylated and unmethylated control (MQ/UQ). (B) High methylation of RASSF6 is correlated to an unfavorable outcome. (C) High methylation of RASSF6 is highly correlated to 1p deletion and MYCN amplification.

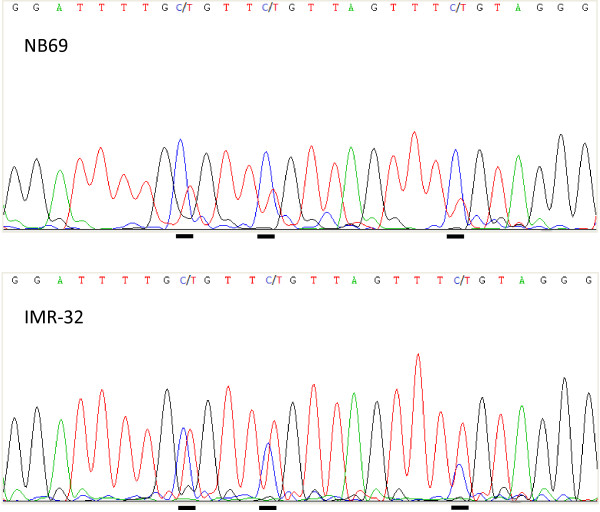

The CpG site present on the 27K methylation array, located in the gene body of RASSF7 was fully methylated in all four NB cell lines. Bisulfite sequencing of a fragment surrounding the transcriptional start site of RASSF7 showed that eight of the nine (89%) NB cell lines were methylated, although to various levels (Figure 3). Bisulfite sequencing thus showed that the NB cell lines were methylated also around the RASSF7 transcription start site.

Figure 3.

Bisulfite sequencing of RASSF7. Top sequence NB69 and bottom sequence IMR-32. Cytosines/thymines in the CpG dinucleotide are underlined. C in the sequence indicates methylation, C/T indicates partial methylation and T indicates unmethylated CpG sites.

RASSF8 was unmethylated in all NB cell lines according to the 27K methylation array and bisulfite sequencing confirmed the array results. RASSF8 was also unmethylated in the NB tumor material.

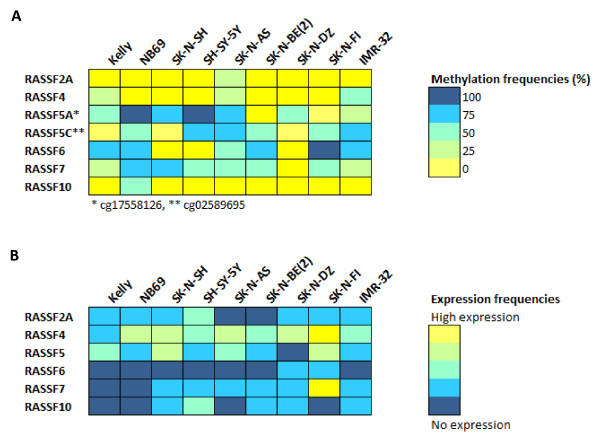

RASSF10 was unmethylated in eight of the nine (89%) cell lines whereas NB69 was partially methylated at all CpG sites. The methylation results are summarized in Figure 4A and the methylation frequencies of each CpG site on the 27K methylation array are listed in Table 3.

Figure 4.

Summary of RASSF gene expression and methylation. (A) Summary of RASSF gene methylation in NB cell lines. Methylation frequencies for each gene and NB cell line are indicated with a color code where fully methylated is marked with blue and unmethylated is marked with yellow. (B) Summary of RASSF gene expression in NB cell lines. mRNA expression levels for each gene and NB cell line are marked with a color code where blue indicate absent expression and yellow high expression level.

Expression analysis and up-regulation after 5-aza-dC and TSA treatment

RASSF2A mRNA expression in NB cell lines was very low overall, with no difference in expression between methylated and unmethylated cell lines (Figure 4B). Quantitative real-time PCR showed that RASSF2A expression was up-regulated in 4/9 NB cell lines after 5-Aza-dC/TSA treatment (Table 4).

Table 4.

Up-regulation of gene expression following treatment with 5-Aza-dC or 5-Aza-dC/TSA

| Rassf2A* | Rassf4* | Rassf5** | Rassf6** | Rassf7** | Rassf10* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kelly |

AZA |

|

|

|

UD |

|

|

| |

AZA/TSA |

|

↑ |

|

UD |

↑ |

↑ |

| NB69 |

AZA |

|

|

↑ |

UD |

|

|

| |

AZA/TSA |

↑ |

|

↑ |

UD |

|

|

| SK-N-SH |

AZA |

|

|

|

UD |

|

|

| |

AZA/TSA |

|

|

|

UD |

|

|

| SH-SY-5Y |

AZA |

|

|

↑ |

UD |

↑ |

|

| |

AZA/TSA |

↑ |

|

↑ |

UD |

|

|

| SK-N-AS |

AZA |

|

↑ |

↑ |

UD |

|

|

| |

AZA/TSA |

|

↑ |

|

UD |

|

|

| SK-N-BE(2) |

AZA |

|

↑ |

↑ |

UD |

|

|

| |

AZA/TSA |

|

↑ |

↑ |

UD |

↑ |

|

| SK-N-DZ |

AZA |

|

|

↑ |

|

↑ |

↑ |

| |

AZA/TSA |

|

|

↑ |

|

↑ |

|

| SK-N-FI |

AZA |

|

↑ |

|

|

|

|

| |

AZA/TSA |

↑ |

↑ |

|

|

|

|

| IMR-32 |

AZA |

|

↑ |

↑ |

UD |

|

|

| AZA/TSA | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | UD |

Arrows indicate a more than 2 fold up-regulation of gene expression following treatment.

UD, undetermined - gene transcripts not detected in the PCR amplification.

*qRT-PCR, **End-point RT-PCR.

RASSF4 expression was present in all NB cell lines with a lower expression in Kelly, SH-SY-5Y, SK-N-BE(2) and IMR-32 (Figure 4B). The lower expression in Kelly, IMR-32 and SK-N-BE correlated with the presence of methylation according to either COBRA or 27K methylation array results. Further, the three cell lines (SK-N-AS, IMR-32 and SK-N-BE(2)), that showed low level of methylation on the 27K methylation array were up-regulated following treatment with 5-Aza-dC and even more up-regulated following a combined treatment with 5-Aza-dC and TSA. The methylated cell line Kelly also showed up-regulation of RASSF4 following a combined treatment with 5-Aza-dC and TSA (Table 4).

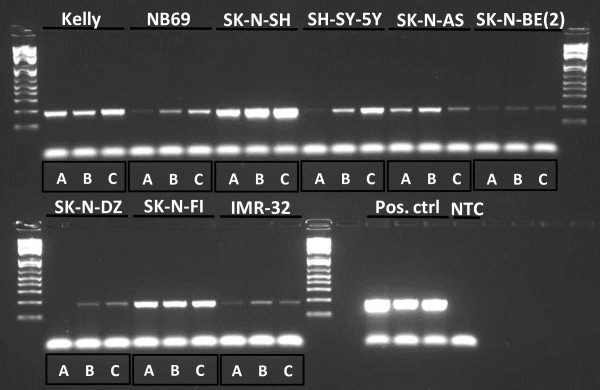

RASSF5 expression varied between the cell lines and RASSF5 mRNAs was up-regulated after epigenetic treatment in 6/9 of the NB cell lines (see Figure 4B, Figure 5 and Table 4). The highest level of up-regulation was seen in the cell lines IMR-32 and SH-SY-5Y.

Figure 5.

Up-regulation of RASSF5 expression following treatment with 5-Aza-dC and TSA. RASSF5 end-point RT-PCR samples from left to right: Kelly A, B, C, NB69 A, B, C, SK-N-SH A, B, C, SH-SY-5Y A, B, C, SK-N-AS A, B, C, SK-N-BE(2) A, B, C, SK-N-DZ A, B, C, SK-N-FI A, B, C, IMR-32 A, B, C. Three positive controls (Pos. ctrl) and one non template control (NTC). A = untreated, B = AZA treated and C = AZA/TSA treated.

RASSF6 was not expressed in seven out of the nine (78%) NB cell lines and the remaining two had expression just above the detection limit. No up-regulation was seen following treatment with either 5-Aza-dC alone or in conjunction with TSA (Figure 4B and Table 4).

RASSF7 expression was overall very low in the NB cell lines with exception for SK-N-FI which had moderate expression (Figure 4B). RASSF7 expression was strongly up-regulated in the methylated cell line SK-N-BE(2) after treatment with 5-Aza-dC in conjunction with TSA with both cDNA microarray and end-point RT-PCR. RASSF7 was up-regulated in 4/9 NB cell lines following at least one of the treatments (Table 4).

Very low RASSF10 expression was detected in five of the nine (56%) NB cell lines (Figure 4B). RASSF10 expression was not up-regulated following epigenetic treatment in most of the NB cell lines (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated whether the RASSF family genes are epigenetically silenced in NB. Data from our previously performed 27K methylation array showed that members of the RASSF gene family were methylated in NB cell lines and tumors [9]. The methylation status observed with the 27K methylation array was verified by DNA methylation analysis using bisulfite sequencing, MSP or COBRA, of the corresponding CpG island. DNA methylation was most commonly observed in RASSF7 (eight out of nine cell lines methylated), RASSF5 (six to seven out of nine cell lines methylated depending on region analyzed) and RASSF6 (six out of nine cell lines methylated) (Figure 4A). Gene expression analysis performed on NB cell lines showed in general low to moderate expression of the RASSF genes (Figure 4B). RASSF4 had the highest expression in the NB cell lines whereas the mRNA levels of RASSF6, RASSF7 and RASSF10 were either below detection levels or very low in most NB cell lines. Also, the mRNA levels of RASSF2A and RASSF5 were low in general. In order to see if RASSF gene expression could be restored, NB cell lines were treated with 5-Aza-dC/or TSA. Gene expression of most of the RASSF genes (RASSF2A, RASSF4, RASSF5, RASSF7 and RASSF10) was up-regulated following epigenetic treatment, suggesting these genes may be epigenetically regulated. The concentration of each epigenetic drug and the treatment time will most certainly affect the results of up-regulation. The chosen conditions of drugs and treatment times were based upon optimization conditions where re-expression of a panel of known methylated genes occurred [9]. More gene-specific optimizations of the epigenetic drug treatment conditions may be necessary in order to explore the re-activation potential fully. Also, up-regulation of a gene may be the result of their up-stream regulators being affected by treatment and it is also possible that other epigenetic mechanisms than DNA methylation are responsible for the up-regulation. Genes belonging to the RASSF family are generally considered as TSGs and many of the members have been reported as silenced by promoter methylation in human cancers, (Table 5).

Table 5.

Information of theRASSFgenes studied in relation to tumorigenesis

| Symbol | Chr | Product | Methylated in cancer | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

RASSF1A |

3p21 |

Ras association domain family member 1 |

NB tumors and cell lines [4] as well as various human cancers, reviewed in [6] |

TSG involved in regulation of cell proliferation. Promotes apoptosis and cell cycle arrest, involved in migration and maintenance of genomic stability (reviewed in [6]). KO of RASSF1A in mice enhances spontaneous tumor formation [18]; [19] |

|

RASSF2 |

20p13 |

Ras association domain family member 2 |

Colorectal cancer [13], gastric cancer [20], nasopharyngeal carcinoma [21], breast-, lung and NSCLC tumors [22], thyroid cancer [23], pancreatic cancer [24] |

Function as a TSG, reduces colony formation, promotes apoptosis and cell cycle arrest [25]; [15]; [21]; [22]; [23] |

|

RASSF4 |

10q11 |

Ras association domain family member 4 |

Kidney-, breast- and lung cancer cell lines, breast- and lung primary tumors [14] |

Have growth inhibitory properties and promotes apoptosis in lung- and breast tumor cell lines [14] |

|

RASSF5 |

1q32 |

Ras association domain family member 5 |

NB cell lines [26]; [27], lung-, breast-, colorectal-, and kidney tumor cell lines and in primary NSCLC tumors [28], Wilms tumor [29], CCRCC [30], gastric cancer [20], colon cancer [13], squamous cell cancer of head and neck [31], hepatocellular carcinoma [32] |

Also called NORE1 and forms heterodimers with RASSF1A [33]. Associate with microtubules and act growth inhibitory by a process involving p53. Promotes apoptosis when overexpressed or in the presence of activated Ras [34]. Neuroblastoma tumors, especially non MYCN-amplified, show suppressed NORE1A expression [27] |

|

RASSF6 |

4q13 |

Ras association domain family member 6 |

Childhood leukemia [10] |

Putative TSG in childhood leukemia [10]. Promotes apoptosis [35]. Downregulated at both mRNA and protein level in gastric cancer. Gastric cancer patients with RASSF6-negative tumors had worse outcome and higher recurrence rate than patients with RASSF6-positive tumors [36] |

|

RASSF7 |

11p15 |

Ras association domain family (N-terminal) member 7 |

|

Centrosome associated protein necessary for spindle formation and completion of mitosis in the neural tube in Xenopus [8]. Required for completion of mitosis in human cells and KO results in mitotic arrest [37] |

|

RASSF8 |

12p12 |

Ras association domain family (N-terminal) member 8 |

Childhood leukemia cell lines [10] |

TSG candidate in lung cancer [38]. KO enhances anchorage independent growth in soft agar and promotes tumor formation in mice [39] |

| RASSF10 | 11p15 | Ras association domain family (N-terminal) member 10 | Childhood leukemia [10], thyroid cancer [40], primary glioblastomas and astrocytomas [41], malign melanoma [42] | Suggested as a regulator of mitosis. Over-expression decrease colony formation in soft agar [41] |

Chr, chromosome; TSG, tumor suppressor gene; KO, knock out; NSCLS, non-small cell lung cancer; CCRCC, clear cell renal cell carcinoma; LOH, loss of heterozygosity.

RASSF1A is a TSG involved in a range of cellular processes that are essential for normal cell growth control. Rassf1a is one of the most commonly inactivated proteins in cancer and inactivation by promotor hypermethylation is a common event in various human malignancies, including NB [4]. Demonstrating the validity of our 27K methylation array data, we detected dense RASSF1A methylation of NB primary tumors and cell lines, which is in agreement with published data.

RASSF2A mRNA expression was in the current study generally low in NB cell lines and up-regulation of RASSF2A was seen following a combined treatment with 5-Aza-dC and TSA (4/9 NB cell lines) even though methylation at the RASSF2A CpG island was not commonly observed.

RASSF4 mRNA expression was detected in all NB cell lines and 5-Aza-dC and TSA treatment resulted in up-regulation of RASSF4 mRNA levels in 5/9 NB cell lines. The strongest up-regulation was detected in the cell line IMR-32 which also showed the highest methylation level.

RASSF5, also called NORE1 (Novel Ras Effector 1), is localized at 1q32.1 and has a 60% similarity to RASSF1A, the most commonly described methylated gene in cancer so far. The RASSF5 gene encodes at least three different isoforms due to different promoter usage and alternative splicing. Two of the RASSF5 isoforms, RASSF5A and RASSF5C are broadly expressed in most normal tissues. RASSF5A is the longest isoform transcribed from the most 5′-promoter and the isoform RASSF5B is produced by alternative splicing. The shorter isoform RASSF5C is transcribed from a more downstream promoter. Promoter methylation of RASSF5A has been reported to not occur in primary NB tumors and there are some conflicting data concerning methylation of NB cell lines, where NB cell lines have been described as low methylated or unmethylated in different studies [26,27]. Interestingly RASSF5 was recently shown to be demethylated and up-regulated in the NB cell line SK-N-BE during ATRA-induced differentiation [43], suggesting that RASSF5 could be aberrantly methylated in undifferentiated NB tumors cells but demethylated and re-expressed through differentiation. According to our 27K methylation array data, two CpG sites were methylated in NB primary tumors and cell lines. The methylated CpG sites were located in different RASSF5 promotor CpG islands. The 27K methylation array site cg17558126 was located in the most 5′-promoter where transcription of RASSF5A starts and cg02589695 were located in a downstream promoter were the RASSF5C transcript starts. Bisulfite sequencing of the two regions revealed that both CpG sites present on the 27K methylation array were indeed methylated in most NB cell lines (Figure 4A). The methylation status of the CpG sites surrounding cg17558126 (RASSF5A) was highly variable throughout the CpG island, but most sites showed partial methylation, whereas the CpG sites surrounding cg02589695 (RASSF5C) were unmethylated in all NB cell lines. The variable methylation of CpG sites in this island might explain why there are conflicting published data regarding the methylation status of RASSF5A in NB cell lines. Gene expression of RASSF5A have also been described as low in NB cell lines, with the highest expression in SK-N-SH and absent expression in IMR-32 [26], which is in agreement with our data (Figure 4A and 4B). RASSF5 mRNA expression was in this study up-regulated for several NB cell lines. For example, the methylated cell line SH-SY-5Y was up-regulated after 5-Aza-dC treatment and even more up-regulated following a combined treatment with both 5-Aza-dC and TSA (Table 4). Two of the analyzed RASSF5 CpG sites on the 27K methylation array were significantly more methylated in INRG stage M tumors compared to L tumors (Figure 1B). Also, RASSF5A methylation was highly correlated to MYCN amplification (Figure 1B). RASSF5A mRNA expression have also been reported as frequently down-regulated in NB and pheochromocytoma primary tumors and lower RASSF5A expression was seen in NB tumors without MYCN-amplification compared to MYCN-amplified tumors [27]. The methylation beta-value for two of the RASSF5 sites was significantly higher in MYCN-amplified tumors compared to non-amplified tumors which contradicts an earlier report that showed lower expression of this gene in non-MYCN-amplified tumors [27].

RASSF6, located at chromosome region 4q13.3 has recently been suggested as a TSG candidate in childhood leukemia and was found to be silenced by heavy methylation across the whole CpG island in leukemia cell lines [10]. In the current study, RASSF6 promoter methylation was found in 6/9 NB cell lines and RASSF6 expression was absent or just above detection level in the panel of NB cell lines (Figure 4A and 4B). High methylation of RASSF6 was significantly correlated to unfavorable outcome (5-OS), 1p deletion and MYCN amplification in our patient cohort (Figure 2B and 2C). Recently, RASSF6 was shown to be down-regulated at both mRNA and protein level in gastric cancer tumors and loss of RASSF6 expression correlated with poor survival and increased tumor recurrence rate [36]. Functional studies have indicated that RASSF6 is involved in promoting apoptosis [35].

RASSF7, also known as HRC1 (HRAS1 cluster 1), is located at chromosome region 11p15.5 and lacks the conserved SARAH domain present in RASSF1-6. To our knowledge, there are yet no reports of epigenetic silencing of RASSF7 in cancer but important functions have been reported (Table 5). In this study, bisulfite sequencing showed methylation of the RASSF7 promotor CpG sites in 8/9 NB cell lines (Figure 4A). All four NB cell lines present on the 27K methylation array were heavily methylated (84-96%) at the analyzed CpG site. Interestingly, the mRNA expression of RASSF7 was very low or absent in most NB cell lines (Figure 4B). According to our cDNA microarray analysis the methylated NB cell line SK-N-BE was strongly up-regulated following epigenetic treatment, which was verified with end-point RT-PCR (Table 4).

RASSF10, located at 11p15.2, has recently been reported as methylated and silenced in childhood leukemia [10], thyroid cancer [40] and in astrocytic glioma [41]. In this study the RASSF10 mRNA expression was absent or just above the detection level in NB cell lines but low methylation was found in only 1/9 NB cell lines (Figure 4A and B).

Collectively, the RASSF family members have been demonstrated to have several tumor suppressive properties (Table 5). Although RASSF proteins lack catalytic activity, they are suggested to be non-enzymatic adaptors that are involved in growth and tumor suppression. The molecular mechanisms behind their growth suppressing properties are not yet elucidated but a number of reports show association with microtubules or centromeres indicating that the RASSF genes are important in microtubule dynamics and mitosis. In addition, the RASSF family genes participate in regulation of apoptosis and epigenetic silencing of RASSF genes may contribute to cancer by preventing RAS induced-apoptosis. In a normal cell, there is an important balance between signaling pathways that promote survival and those who promote apoptosis. If RASSF genes are silenced, the pro-apoptotic effects of RAS signaling may be lost which may favor the balance towards the pro-survival PI3 kinase pathway. Future studies regarding the exact function of the RASSF family genes and their interacting partners are essential to elucidate the role that epigenetic silencing of RASSF genes might play in NB and cancer in general.

Several genes from various cellular pathways have been reported as epigenetically silenced by DNA methylation in NB. For example, Caspase-8 (CASP8) located at 2q33 was one of the first genes to be reported as methylated in NB [44]. Aberrantly methylated genes could in the future be used in clinical patient stratification as biomarkers or as therapeutic targets. Our group and many others have shown that DNA methylation of single genes or a selected group of genes, are able to predict patient outcome, for a review see Decock et al., [45]. Epigenetic inactivation of RASSF1A has been reported as associated with high risk disease, age >1 year and poor survival for NB patients [46]. Further, RASSF1A hypermethylation in serum from patients with NB has been reported as a reliable prognostic predictor [47].

In summary, in addition to RASSF1A which is already known as frequently methylated in NB, this study highlights the RASSF gene family members RASSF5, RASSF6 and RASSF7 as promising candidates for further analysis in NB. These three genes are targeted by DNA methylation in NB primary tumors and cell lines and show low levels of mRNA expression in NB cell lines. Also, CpG site specific DNA methylation of RASSF5 and RASSF6 was able to significantly discriminate between different subgroups of NB.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AD carried out the experiments, analyzed the results and drafted the manuscript. HC planned and coordinated the study, performed experimental and statistical analysis and revised the manuscript. TM and PK provided clinical information. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Anna Djos, Email: anna.djos@clingen.gu.se.

Tommy Martinsson, Email: tommy.martinsson@gu.se.

Per Kogner, Email: per.kogner@ki.se.

Helena Carén, Email: helena.caren@gu.se.

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Society, the Children’s Cancer Foundation, the Nilsson-Ehle Foundation, the Assar Gabrielsson Foundation and the Wilhelm and Martina Lundgren Research Foundation. We are grateful for help and access to instrumentation provided by the Sahlgrenska Academy Genomics Core Facility.

References

- Johnsen JI, Kogner P, Albihn A, Henriksson MA. Embryonal neural tumours and cell death. Apoptosis. 2009;14(4):424–438. doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0325-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodeur GM. Neuroblastoma: biological insights into a clinical enigma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(3):203–216. doi: 10.1038/nrc1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carén H, Kryh H, Nethander M, Sjöberg RM, Träger C, Nilsson S, Abrahamsson J, Kogner P, Martinsson T. High-risk neuroblastoma tumors with 11q-deletion display a poor prognostic, chromosome instability phenotype with later onset. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(9):4323–4328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910684107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astuti D, Agathanggelou A, Honorio S, Dallol A, Martinsson T, Kogner P, Cummins C, Neumann HP, Voutilainen R, Dahia P. et al. RASSF1A promoter region CpG island hypermethylation in phaeochromocytomas and neuroblastoma tumours. Oncogene. 2001;20(51):7573–7577. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejeskär K, Aburatani H, Abrahamsson J, Kogner P, Martinsson T. Loss of heterozygosity of 3p markers in neuroblastoma tumours implicate a tumour-suppressor locus distal to the FHIT gene. Br J Cancer. 1998;77(11):1787–1791. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donninger H, Vos MD, Clark GJ. The RASSF1A tumor suppressor. J Cell Sci. 2007;120(Pt 18):3163–3172. doi: 10.1242/jcs.010389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cully M, Downward J. SnapShot: Ras Signaling. Cell. 2008;133(7):1292–1292 e1291. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood V, Manbodh R, Sheppard C, Chalmers AD. RASSF7 is a member of a new family of RAS association domain-containing proteins and is required for completing mitosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19(4):1772–1782. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-07-0652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carén H, Djos A, Nethander M, Sjöberg RM, Kogner P, Enström C, Nilsson S, Martinsson T. Identification of epigenetically regulated genes that predict patient outcome in neuroblastoma. BMC Cancer. 2011;11(1):66. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesson LB, Dunwell TL, Cooper WN, Catchpoole D, Brini AT, Chiaramonte R, Griffiths M, Chalmers AD, Maher ER, Latif F. The novel RASSF6 and RASSF10 candidate tumour suppressor genes are frequently epigenetically inactivated in childhood leukaemias. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:42. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kryh H, Carén H, Erichsen J, Sjöberg RM, Abrahamsson J, Kogner P, Martinsson T. Comprehensive SNP array study of frequently used neuroblastoma cell lines; copy neutral loss of heterozygosity is common in the cell lines but uncommon in primary tumors. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:443. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tusnady GE, Simon I, Varadi A, Aranyi T. BiSearch: primer-design and search tool for PCR on bisulfite-treated genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(1):e9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesson LB, Wilson R, Morton D, Adams C, Walker M, Maher ER, Latif F. CpG island promoter hypermethylation of a novel Ras-effector gene RASSF2A is an early event in colon carcinogenesis and correlates inversely with K-ras mutations. Oncogene. 2005;24(24):3987–3994. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckfeld K, Hesson L, Vos MD, Bieche I, Latif F, Clark GJ. RASSF4/AD037 is a potential ras effector/tumor suppressor of the RASSF family. Cancer Res. 2004;64(23):8688–8693. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akino K, Toyota M, Suzuki H, Mita H, Sasaki Y, Ohe-Toyota M, Issa JP, Hinoda Y, Imai K, Tokino T. The Ras effector RASSF2 is a novel tumor-suppressor gene in human colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(1):156–169. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Z, Laird PW. COBRA: a sensitive and quantitative DNA methylation assay. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(12):2532–2534. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.12.2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carén H, Fransson S, Ejeskär K, Kogner P, Martinsson T. Genetic and epigenetic changes in the common 1p36 deletion in neuroblastoma tumours. Br J Cancer. 2007;97(10):1416–1424. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tommasi S, Dammann R, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Liu L, Tsark WM, Wilczynski SP, Li J, You M, Pfeifer GP. Tumor susceptibility of Rassf1a knockout mice. Cancer Res. 2005;65(1):92–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Weyden L, Tachibana KK, Gonzalez MA, Adams DJ, Ng BL, Petty R, Venkitaraman AR, Arends MJ, Bradley A. The RASSF1A isoform of RASSF1 promotes microtubule stability and suppresses tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(18):8356–8367. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.18.8356-8367.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoh M, Tamura G, Honda T, Homma N, Terashima M, Nishizuka S, Motoyama T. RASSF2, a potential tumour suppressor, is silenced by CpG island hypermethylation in gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;93(12):1395–1399. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Sun D. Van do N, Tang A, Hu L, Huang G: Inactivation of RASSF2A by promoter methylation correlates with lymph node metastasis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(1):32–38. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper WN, Dickinson RE, Dallol A, Grigorieva EV, Pavlova TV, Hesson LB, Bieche I, Broggini M, Maher ER, Zabarovsky ER. et al. Epigenetic regulation of the ras effector/tumour suppressor RASSF2 in breast and lung cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27(12):1805–1811. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schagdarsurengin U, Richter AM, Hornung J, Lange C, Steinmann K, Dammann RH. Frequent epigenetic inactivation of RASSF2 in thyroid cancer and functional consequences. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:264. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Cui Q, Lu Z, Chen J. Aberrant Methylation of RASSF2A in Human Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma and Its Relation to Clinicopathologic Features. Pancreas. 2012;41(2):206–211. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318223d1a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos MD, Ellis CA, Elam C, Ulku AS, Taylor BJ, Clark GJ. RASSF2 is a novel K-Ras-specific effector and potential tumor suppressor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(30):28045–28051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300554200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazcoz P, Munoz J, Nistal M, Pestana A, Encio I, Castresana JS. Frequent promoter hypermethylation of RASSF1A and CASP8 in neuroblastoma. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:254. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geli J, Kogner P, Lanner F, Natalishvili N, Juhlin C, Kiss N, Clark GJ, Ekstrom TJ, Farnebo F, Larsson C. Assessment of NORE1A as a putative tumor suppressor in human neuroblastoma. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(2):389–394. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesson L, Dallol A, Minna JD, Maher ER, Latif F. NORE1A, a homologue of RASSF1A tumour suppressor gene is inactivated in human cancers. Oncogene. 2003;22(6):947–954. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris MR, Hesson LB, Wagner KJ, Morgan NV, Astuti D, Lees RD, Cooper WN, Lee J, Gentle D, Macdonald F. et al. Multigene methylation analysis of Wilms’ tumour and adult renal cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2003;22(43):6794–6801. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Lui WO, Vos MD, Clark GJ, Takahashi M, Schoumans J, Khoo SK, Petillo D, Lavery T, Sugimura J. et al. The t(1;3) breakpoint-spanning genes LSAMP and NORE1 are involved in clear cell renal cell carcinomas. Cancer Cell. 2003;4(5):405–413. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann K, Sandner A, Schagdarsurengin U, Dammann RH. Frequent promoter hypermethylation of tumor-related genes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2009;22(6):1519–1526. doi: 10.3892/or_00000596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macheiner D, Gauglhofer C, Rodgarkia-Dara C, Grusch M, Brachner A, Bichler C, Kandioler D, Sutterluty H, Mikulits W, Schulte-Hermann R. et al. NORE1B is a putative tumor suppressor in hepatocarcinogenesis and may act via RASSF1A. Cancer Res. 2009;69(1):235–242. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Vega S, Khokhlatchev A, Nedwidek M, Zhang XF, Dammann R, Pfeifer GP, Avruch J. The putative tumor suppressor RASSF1A homodimerizes and heterodimerizes with the Ras-GTP binding protein Nore1. Oncogene. 2002;21(9):1381–1390. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvisi DF, Donninger H, Vos MD, Birrer MJ, Gordon L, Leaner V, Clark GJ. NORE1A tumor suppressor candidate modulates p21CIP1 via p53. Cancer Res. 2009;69(11):4629–4637. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M, Hirabayashi S, Fujiwara N, Mori H, Kawata A, Iida J, Bao Y, Sato Y, Iida T, Sugimura H. et al. Ras-association domain family protein 6 induces apoptosis via both caspase-dependent and caspase-independent pathways. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313(7):1484–1495. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y, Wang Q, Zhou C, Yan D, Qiu G, Yang C, Tang H, Peng Z. Decreased Expression of RASSF6 Is a Novel Independent Prognostic Marker of a Worse Outcome in Gastric Cancer Patients after Curative Surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011 Dec;18(13):3858–67. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1668-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recino A, Sherwood V, Flaxman A, Cooper WN, Latif F, Ward A, Chalmers AD. Human RASSF7 regulates the microtubule cytoskeleton and is required for spindle formation, Aurora B activation and chromosomal congression during mitosis. Biochem J. 2010;430(2):207–213. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falvella FS, Manenti G, Spinola M, Pignatiello C, Conti B, Pastorino U, Dragani TA. Identification of RASSF8 as a candidate lung tumor suppressor gene. Oncogene. 2006;25(28):3934–3938. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock FE, Underhill-Day N, Dunwell T, Matallanas D, Cooper W, Hesson L, Recino A, Ward A, Pavlova T, Zabarovsky E. et al. The RASSF8 candidate tumor suppressor inhibits cell growth and regulates the Wnt and NF-kappaB signaling pathways. Oncogene. 2010;29(30):4307–4316. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schagdarsurengin U, Richter AM, Wohler C, Dammann RH. Frequent epigenetic inactivation of RASSF10 in thyroid cancer. Epigenetics. 2009;4(8):571–576. doi: 10.4161/epi.4.8.10056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill VK, Underhill-Day N, Krex D, Robel K, Sangan CB, Summersgill HR, Morris M, Gentle D, Chalmers AD, Maher ER. et al. Epigenetic inactivation of the RASSF10 candidate tumor suppressor gene is a frequent and an early event in gliomagenesis. Oncogene. 2011;30(8):978–989. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmbold P, Richter AM, Walesch S, Skorokhod A, Marsch WC, Enk A, Dammann RH. RASSF10 Promoter Hypermethylation Is Frequent in Malignant Melanoma of the Skin but Uncommon in Nevus Cell Nevi. J Invest Dermatol. 2012 Mar;132(3 Pt 1):687–94. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Foley N, Bryan K, Watters KM, Bray I, Murphy DM, Buckley PG, Stallings RL. MicroRNA mediates DNA demethylation events triggered by retinoic acid during neuroblastoma cell differentiation. Cancer Res. 2010;70(20):7874–7881. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitz T, Wei T, Valentine MB, Vanin EF, Grenet J, Valentine VA, Behm FG, Look AT, Lahti JM, Kidd VJ. Caspase 8 is deleted or silenced preferentially in childhood neuroblastomas with amplification of MYCN. Nat Med. 2000;6(5):529–535. doi: 10.1038/75007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decock A, Ongenaert M, Vandesompele J, Speleman F. Neuroblastoma epigenetics: from candidate gene approaches to genome-wide screenings. Epigenetics. 2011;6(8):962–970. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.8.16516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Zage P, Kagan D, Tian Y, Seshadri R, Salwen HR, Liu S, Chlenski A, Cohn SL. Association of epigenetic inactivation of RASSF1A with poor outcome in human neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(24):8493–8500. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misawa A, Tanaka S, Yagyu S, Tsuchiya K, Iehara T, Sugimoto T, Hosoi H. RASSF1A hypermethylation in pretreatment serum DNA of neuroblastoma patients: a prognostic marker. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(2):399–404. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]