Abstract

The C4 enzyme pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase is encoded by a single gene, Pdk, in the C4 plant Flaveria trinervia. This gene also encodes enzyme isoforms located in the chloroplast and in the cytosol that do not have a function in C4 photosynthesis. Our goal is to identify cis-acting DNA sequences that regulate the expression of the gene that is active in the C4 cycle. We fused 1.5 kb of a 5′ flanking region from the Pdk gene, including the entire 5′ untranslated region, to the uidA reporter gene and stably transformed the closely related C4 species Flaveria bidentis. β-Glucuronidase (GUS) activity was detected at high levels in leaf mesophyll cells. GUS activity was detected at lower levels in bundle-sheath cells and stems and at very low levels in roots. This lower-level GUS expression was similar to the distribution of mRNA encoding the nonphotosynthetic form of the enzyme. We conclude that cis-acting DNA sequences controlling the expression of the C4 form in mesophyll cells and the chloroplast form in other cells and organs are co-located within the same 5′ region of the Pdk gene.

PPDK (EC 2.7.9.1) is active in the mesophyll chloroplasts of C4 plants, where it converts pyruvate to PEP, the primary CO2 acceptor (Edwards and Walker, 1983; Hatch, 1987). It has, like the other enzymes of the C4 cycle, evolved from an ancestral C3 form (Moore, 1982). Although the function of PPDK in C3 tissues is not evident yet, it has been suggested that it might be involved in the conversion of the C3 and C4 compounds of amino acids (Aoyagi and Bassham, 1985). Low levels of PPDK have been found in various C3 plants as both chloroplastic and cytoplasmic isoenzymes (Meyer et al., 1982; Aoyagi and Bassham, 1983, 1984a, 1984b; Hata and Matsuoka, 1987). The presence of PPDK in C3 plants and the high similarities of the proteins of C3 and C4 plants (about 80% amino acid sequence identity; Matsuoka et al., 1988; Rosche and Westhoff, 1990; Rosche et al., 1994), as well as bacteria (about 53% amino acid identity with the plant enzymes; Pocalyko et al., 1990; Bruchhaus and Tannich, 1993), suggest a housekeeping function for the ancestral form. The presence of low levels of mRNA encoding PPDK in nonphotosynthetic organs of C4 plants (Glackin and Grula, 1990; Matsuoka, 1990; Sheen, 1991; Rosche and Westhoff, 1995) suggests that a housekeeping form may perform a similar function in these plants. The gene coding for the C4 form could have arisen by a gene-duplication mechanism that left the original gene coding for the housekeeping form. However, the genes coding for PPDK do not fit in this simple evolutionary scenario (Matsuoka, 1995).

Maize has two Pdk genes, one of which encodes a cytoplasmic isoform that is expressed at low levels in all tissues (Sheen, 1991). A second gene encodes both chloroplastic and cytoplasmic forms. A large intron separates the exon encoding the chloroplast transit sequence from the exons encoding the mature polypeptide. An abundant, long transcript encoding the C4 form contains both transit and mature coding regions and is found preferentially in MC. A second transcript containing only the coding region for the mature polypeptide arises from the same gene and was detected in roots at a low level (Hudspeth et al., 1986; Glackin and Grula, 1990).

The genus Flaveria has species with C3 photosynthesis and C4 photosynthesis and those showing intermediate characteristics (Powell, 1978), making it particularly useful for gene comparisons. Rosche et al. (1994) detected only a single Pdk gene in all Flaveria species tested, regardless of the photosynthetic type. The C4 gene is very similar in structure to the dual-function maize gene and shows a similar expression pattern. In the C4 species Flaveria trinervia transcription of the entire gene produces a 3.4-kb mRNA, the expression of which is positively light regulated (Rosche and Westhoff, 1995). The 3.4-kb mRNA and the mature protein are found predominantly, but not exclusively, in MC (Höfer et al., 1992; Rosche and Westhoff, 1995). A shorter transcript of 3.0 kb that codes only for the mature polypeptide was detected at low levels in roots and in darkened stems of F. trinervia (Rosche and Westhoff, 1995). The 3.4-kb mRNA was detected in leaves of C3 and C3-C4 intermediate species of Flaveria, its level showing a correlation with the degree of C4 characteristics in the intermediate species (Rosche et al., 1994).

Therefore, the single Flaveria Pdk gene encodes PPDKs of different function, location, and abundance. The C4 isoform appears to have arisen from a gene encoding a nonphotosynthetic form by the addition of new cis-acting regulatory sequences while preserving the ancestral gene regulatory sequences. We have begun to localize these regulatory sequences by fusing 1.5 kb of the 5′ end of the F. trinervia (C4 species) to the uidA reporter gene. This has been stably transformed into the genome of Flaveria bidentis, a closely related species also showing full development of C4 characteristics. By measuring GUS activities in transgenic plants we can determine whether sequences controlling the expression of the C4 form of PPDK are located within 1.5 kb of the upstream region of the gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Flaveria bidentis plants were grown in a growth chamber with a light/dark cycle of 14/10 h and temperatures of 28/16°C. The light intensity reached about 300 μE m−2 s−1. The plants were watered twice a day and supplied with nutrients every 2nd d. Mature plants used for reillumination experiments were darkened under the same temperature conditions and reilluminated in the same chamber as the light-grown control plants.

Cloning of the uidA Fusion Construct

The 2.8-kb XbaI fragment of the genomic clone in lnFtrpdkA-F containing 1.2 kb of the 5′ untranscribed region of the single Pdk gene of Flaveria trinervia (Rosche and Westhoff, 1995; EMBL accession no. X79095) was used for the reporter gene fusion. The 1257-bp XbaI/ClaI fragment was ligated to a 237-bp PCR fragment extending from the ClaI site to the amino terminal ATG of Pdk, where an artificial NcoI site was created for ligation to the uidA gene from pKIWI105 (Janssen and Gardner, 1989) with an ocs 3′ end. Primers for the PCR reaction were CGTCTGATATGCCCGTAATCTAG (5′) and GCATCCATGGTTCTTCACCTGCTCAATTTCAC (3′). The resulting plasmid was linearized with HindIII and cloned into the binary vector pGA470 (An, 1986).

Transformation

The transformation of F. bidentis was performed as described by Chitty et al. (1994).

GUS Histochemistry

Histochemical staining of GUS activity was done by incubating tissue sections in 1 mg mL−1 5-bromo-4-chloro-3 indolyl β-d-glucuronic acid, 0.1 m Na2HPO4 buffer (pH 7.0), 0.5 mm K3(Fe[CN]6), 0.5 mm K4(Fe[CN]6), and 10 mm EDTA.

Analysis of Nucleic Acids

The preparation of RNA and genomic DNA and its analysis were performed as described earlier (Rosche and Westhoff, 1995), except that Hybond N+ (northern, Amersham) or Hybond N (genomic Southern, Amersham) were used to blot the nucleic acids. Hybridizations were carried out overnight at 64°C in 250 mm Na2HPO4, 2.5 mm EDTA, and 7% (w/v) SDS, pH 7.2 (Church and Gilbert, 1984). Washings were done at hybridization temperature in 5, 2, 1, and 0.5× SSC and 0.1% SDS for 15 to 30 min each. The probes used for the hybridizations of the northern blots were PCR products of the uidA gene in pKIWI105 (1.8 kb), the carboxy-terminal fragment of the PPDK cDNA of F. trinervia (1.8 kb), and the actin gene of F. bidentis (446 bp). The genomic DNA was cut with HindIII and the blot was probed with the BamHI/EcoRI restriction fragment of pKIWI105 containing the entire uidA gene (1.9 kb). Each T-DNA insert should give a unique band on the Southern blot because one HindIII site will be in the flanking plant DNA.

Separation of MC and BSC

BSC strands were separated from the MC by differential homogenization steps and extensive washing of the BSC strands using a modification of the method of Agostino et al. (1989). About 3 g of leaf material was cut into 2-mm strips and homogenized for 10 s at low speed (20% line voltage) in 70 mL of buffer A (0.3 m sorbitol, 25 mm Hepes-KOH, pH 7.4, 10 mm DTT, and 1 mm MgCl2) in an Omnimixer (Sorvall). From this mixture 5 mL was taken as the WLC extract. An additional 5 mL was filtered through a 20-μm net and the filtrate was collected as the MC fraction. A second homogenization for 40 s at full speed (100% line voltage) detached most of the remaining MC from the BSC strands. The BSC strands were collected on a 20-μm net, washed with 20 to 30 mL of buffer B (50 mm Hepes KOH, pH 7.0, 10 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mm EDTA, 1% PVP-40, 5 mm DTT, 2 mm PMSF, and 2 mm ɛ-aminocapronate), and resuspended in 5 mL of buffer B. The remaining cells in each fraction were broken in a glass homogenizer, aliquots were taken for chlorophyll and protein quantitations, and BSA in a final concentration of 0.1% (w/v) was added to the remaining samples before they were frozen in liquid N2. The relative purity of each fraction was determined by measuring the activities of the marker enzymes PEPC (MC specific) and ME (BSC specific) as described by Ashton et al. (1990).

GUS activity was measured in separated cell fractions using the fluorometric assay described by Jefferson et al. (1987). The cell extracts for measuring of GUS in whole leaves, roots, and stems were prepared by grinding the plant material in buffer A with the addition of some sand.

Calculation of Cell-Specific GUS Activities

To calculate the amount of GUS activity in BSC, we measured the GUS activity in WLC, MC, and BSC strand fractions and then used a linear-regression method similar to that described by Stitt and Heldt (1985) to correct for cross-contamination in the BSC fraction. Here the total GUS activity per fraction is defined as the sum of GUS activities coming from the MC and BSC:

|

Because the MC-specific GUS activity is proportional to the activity of the marker enzyme for MC, PEPC (constant a = GUSMC/PEPC), and the GUS activity in BSC preparations is proportional to the activity of ME (constant b = GUSBS/ME), the first equation can be transformed into a function of the form y = a + b(x), where GUStotal/PEPC = y and ME/PEPC = x. The plotting of this function and extrapolation to the axes results in the constants a and b, which can be used to calculate the ratio of MC-specific or BSC-specific GUS activities in each fraction. The reciprocal plot should result in similar values. To minimize errors, we used the activities per volume in each fraction to calculate the linear regressions.

RESULTS

Transformation of F. bidentis

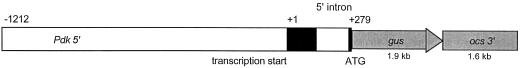

The 5′ region of the F. trinervia Pdk gene extends from position −1212 relative to the start of transcription up to the start of translation at position +279. This includes an exon of 135 bp (exon 1a), an intron of 133 bp in the 5′ untranslated region, and 10 bp of exon 1b in front of the first ATG codon, which initiates translation of the transit peptide (Fig. 1). This gus fusion was transformed into hypocotyl explants of F. bidentis, a species closely related to F. trinervia. Both species exhibit full development of C4 photosynthesis.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the Pdk promoter/uidA construct used for the transformation of F. bidentis. Black boxes indicate the 5′ untranslated exon and the first 10 bp of the next exon in front of the translational start codon. The uidA gene and the ocs 3′ terminator are symbolized as gray boxes.

After callus formation on kanamycin-containing medium we obtained 11 shoots, each from a different callus; 8 of these shoots survived to give mature plants. The plants were transferred to soil and grown in the greenhouse until they set seeds. The seeds of two primary transformants did not germinate. The T1 generation of the remaining six primary transformants were used for the experiments described here, together with two T0 plants, which could be propagated by cuttings. Only one of these T0 plants produced fertile seeds; the resulting T1 plants were included in the analysis.

GUS Expression Changes with Leaf Age

Prior to comparative measurements between different plants we compared the GUS levels between the leaves of single plants. Using the fluorometric quantitation of the conversion of methylumbelliferyl glucuronide by the GUS protein we found the highest levels in leaves at the third or fourth node when counting from the youngest visible node downward. These leaves were already well developed and at least three-quarters in size compared with the largest leaves of the plant. Older leaf pairs showed a significant decrease in GUS activity per milligram protein. The oldest, but not visibly senescent, leaf displayed GUS levels similar to that in stems (data not shown). Although we tried to use tissues of similar age, we could not exclude some variability due to age.

When leaves of the third or fourth node were separated into the top, middle, and basal sections, we obtained the lowest GUS activity in the tip. The levels increased in the middle section and reached 2-fold that of the tip at the basal part, where most of the cell divisions occur (data not shown).

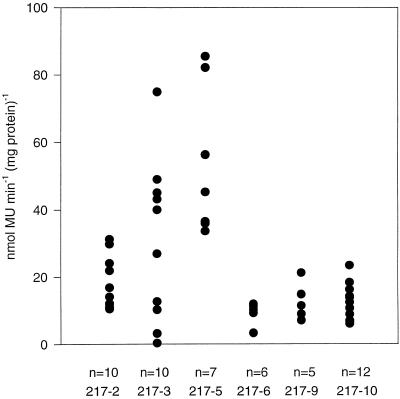

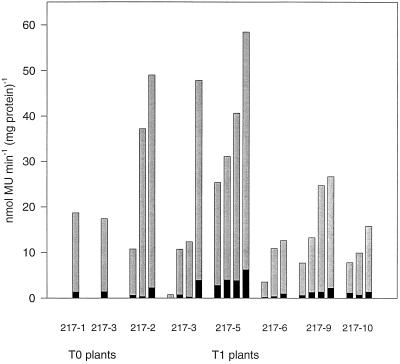

To determine the range of GUS activities in different transgenic lines we prepared leaf extracts from the third leaf pair of plants that were 4 to 6 weeks old. The results of these measurements are shown in Figure 2. Each dot represents one plant. In five lines of T1 plants the highest activities were 2.5 to 4 times that of the lowest levels measured, about what one would expect from the offspring of a self-fertilized T0 plant. One group of T1 plants (217–3) showed considerable variability between 0.3 and 75 nmol methylumbelliferone mg−1 protein min−1.

Figure 2.

Distribution of GUS activities in leaves of transgenic T1 plants. GUS activities in extracts of the third leaf pairs of 4- to 6-week-old plants were quantified using the fluorometric analysis of the conversion of methylumbelliferyl glucuronide. Each circle represents one plant and each column represents the progeny of one T0 plant. MU, Methylumbelliferyl.

Two T0 plants as well as five T1 plants of each of the six fertile transgenic lines were analyzed by Southern-blot hybridization to confirm that the chimeric genes were intact and to estimate the number of the integrated copies (Table I). No correlation was found between the copy number, which ranged from one to six, and the levels of GUS expression.

Table I.

Calculation of GUS activities in MC and BS

| Plant | Transgene Copy No. | GUS Activity in

Cell Fractions

|

Purity of the BSC Fraction | Calculated Activity of the Promoter in Pure BSC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WLC | MC | BSC | ||||

| nmol MUa min−1 mg−1 protein | % | % of WL | ||||

| 217-1 T0 | 1 | 17.3 | 28.3 | 1.4 | 92 | 2.7 |

| 217-3 T0 | 6 | 15.9 | 40.0 | 1.5 | 96 | 4.8 |

| 217-2/3 | 5 | 10.1 | 17.1 | 0.7 | 97 | 0.3 |

| 217-2/6 | 5 | 36.7 | 82.6 | 0.4 | 97 | 0.2 |

| 217-2/8 | 5 | 46.7 | 116.9 | 2.3 | 95 | 0.7 |

| 217-3/1 | 6 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 0.3 | 95 | 1.3 |

| 217-3/2 | 6 | 9.9 | 14.1 | 0.8 | 98 | 4.4 |

| 217-3/3 | 6 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 97 | 6.1 |

| 217-3/12 | 6 | 43.9 | 58.4 | 4.0 | 94 | 1.0 |

| 217-5/3 | 2 | 36.7 | 74.0 | 3.9 | 97 | 4.1 |

| 217-5/6 | 2 | 52.2 | 108.2 | 6.3 | 96 | 3.5 |

| 217-5/8 | 2 | 22.4 | 40.4 | 2.9 | 95 | 5.7 |

| 217-5/9 | 2 | 27.0 | 53.9 | 4.1 | 94 | 7.3 |

| 217-6/1 | 5 | 3.3 | 4.6 | 0.2 | 97 | 4.9 |

| 217-6/4 | 5 | 10.4 | n.d.b | 0.4 | 98 | 4.9 |

| 217-6/6 | 5 | 11.6 | 43.6 | 1.0 | 96 | 1.1 |

| 217-9/1 | 1 | 7.0 | 16.5 | 0.7 | 96 | 3.8 |

| 217-9/2 | 1 | 11.9 | 31.9 | 1.4 | 96 | 7.8 |

| 217-9/3 | 1 | 24.3 | 65.3 | 2.3 | 98 | 1.7 |

| 217-9/5 | 1 | 23.2 | 36.8 | 1.4 | 99 | 1.5 |

| 217-10/1 | 3 | 9.1 | 18.2 | 0.8 | 94 | 3.8 |

| 217-10/2 | 3 | 14.3 | 52.9 | 1.5 | 96 | 2.4 |

| 217-10/37 | 3 | 6.6 | 10.2 | 1.2 | 99 | 9.9 |

GUS activities in the actual cell fractions were measured using the fluorescent assay. The purity of the BSC fraction was estimated using activities of the marker enzymes PEPC and ME. The calculated activity of the promoter/GUS construct in pure BSC fractions was determined by the linear-regression method. The copy number of the integrated T-DNA was determined in genomic Southern blots.

MU, Methylumbelliferyl.

n.d., Not detectable.

Organ-Specific GUS Activities in Transgenic Plants

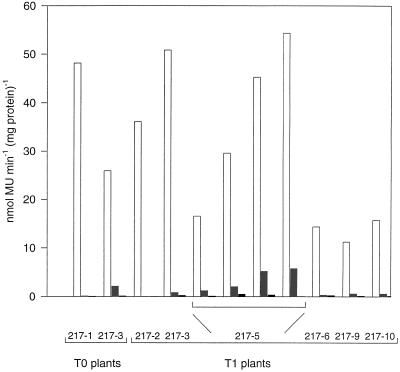

The organ specificity of the promoter construct was investigated in T1 plants of each transgenic line as well as in two T0 plants (Fig. 3). The line 217–5 is represented by four T1 plants exhibiting different levels of GUS expression in leaves. For the preparation of leaf extracts we used the middle sections of the third-youngest leaf pairs. Stem tissues represent the internodal areas between the second and fifth nodes, which are green in both F. trinervia and F. bidentis. Root material was taken from young roots grown in vermiculite.

Figure 3.

Organ specificity of the GUS activity in transgenic plants. GUS activities were measured in the middle parts of leaves (white bars), in the internodal areas of stems (gray bars) between the second and fifth node, and in young roots (black bars) of transgenic plants. Data were obtained from two T0 plants (217–1 and 217–3), one representative each of five transgenic lines (showing medium to high GUS activities in leaves; 217–2, 217–3, 217–6, 217–9, and 217–10) and four plants of line 217–5 expressing a range of GUS activities in leaves. MU, Methylumbelliferyl.

GUS activities in stems ranged from 12 to 0.01% of that found in leaves. The four T1 plants of line 217–5 showed stem activities ranging from 7 to 12% of that in leaves. The levels in roots were slightly above background, ranging from 0.04 to 1.6% of the activities in leaves. A similar distribution of GUS expression in stems, leaves, and roots was found in 25-d-old T1 seedlings (data not shown) as in the more mature plants (analyzed in Fig. 3). The range of the GUS activities in stem tissue relative to the corresponding leaf extracts might be due to high variabilities of the GUS activities at different developmental stages of stems. We tried to circumvent developmental differences by pooling the stem sections between the second and the fifth node. However, we cannot exclude the possibility of varying amounts of lignified material, leading to high variations of the measured GUS activities on a protein basis. The results shown here do prove, however, that the promoter is expressed mainly in leaves and to a lesser degree in stems.

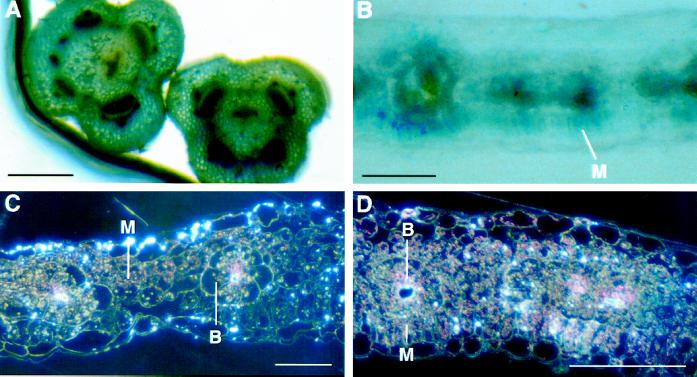

The GUS staining in stems was visible mainly in the vascular bundles and a faint staining was seen in the MC between them (Fig. 4A). As the stem aged, the pronounced vascular staining decreased.

Figure 4.

Histochemical analysis of GUS activity. A, Sections of young stems incubated for 2 h. Bar = 1 mm. B, Leaf section incubated for 20 min. C and D, Leaf sections incubated for 2 h viewed under dark-field microscopy. Bars = 100 μm in B, C, and D. M, MC; B, BSC.

GUS Expression in MC and BSC

The function of PPDK in the C4 cycle of photosynthesis is restricted to the MC, but small amounts of transcripts and proteins for this enzyme have been found in BSC as well. We determined whether the promoter construct was sufficient to direct a similar distribution of GUS activity. When leaf sections from T0 and T1 plants were incubated in 5-bromo-4-chloro-3 indolyl β-d-glucuronic acid for periods of up to 30 min, the indigo GUS product appeared first in MC, as expected (Fig. 4B). Some indigo was also detected in BSC. Epidermal cells were not stained. However, longer incubation resulted in the accumulation of GUS product (seen as a red birefringence in dark-field microscopy) in both cell types and in most cells of veins (Fig. 4C). Incubation times of several hours or more gave as much GUS product in veins as in MC (Fig. 4D). GUS product was even detectable in epidermal cells.

The equivocal results from the histochemical analysis of GUS distribution led us to measure activity directly in isolated cell preparations. In C4 plants the BSC are encased by thick cell walls with no intercellular spaces between adjacent BS. Differential homogenization of leaves allows one to prepare relatively pure bundle-sheath strands consisting of BS and veins (Agostino et al., 1989). However, in C4 plants of the genus Flaveria it is not possible to make MC preparations with a similar degree of purity. The purity of any cell fraction can be accurately determined by measuring the activities of selected C4 enzymes, which have been shown to be cell specific in a wide range of C4 plants (Hatch, 1987). We used PEPC and ME as marker enzymes for MC and BS, respectively, and routinely obtained bundle-sheath preparations, which were about 95% pure. Mesophyll preparations were generally only 60 to 70% pure. We compared the measured GUS activities of bundle-sheath preparations with WL extracts to obtain estimates for MC. For the calculation of GUS activities in pure BS we used the linear-regression method as described in Methods. Since this method is based on the relation of GUS activities to the marker enzymes, it is independent of the purity of the actual cell preparations. The measured GUS activities and calculated values for pure BS are listed in Table I.

The results for two T0 plants and three to four T1 plants of each transgenic line are shown in Figure 5. The estimated GUS activities in bundle-sheath strands vary between 0.2 and 10% of the activities in whole leaves. Within each set of T1 siblings the values diverge to a lesser degree. Based on these measurements we deduce that the promoter construct is mainly expressed in MC but that there is also a low level of expression in BS. We have no data that help us to determine whether any of the GUS activity measured in our bundle-sheath strand preparations is due to promoter activity in vein cells. The quantitative measurements show that the high levels of GUS in BS and veins seen in the histochemical analysis are artifacts.

Figure 5.

Measured GUS activities in extracts of whole leaves (gray bars) compared with BSC (black bars). The BSC preparations were at least 95% pure. The purity was calculated using the activities of the marker enzymes for both cell types. MU, Methylumbelliferyl.

Histochemical staining for GUS activity in young F. bidentis leaves has proven to be difficult because of poor substrate penetration. When young leaves were cut into thin sections, we could observe staining at the cut edges and see a good correlation between the degree of vascularization and the amount of GUS activity (data not shown). Because full development of C4 Kranz anatomy is dependent on complete vascularization of the leaf, this correlation suggests that high-level expression of the Pdk promoter is dependent on cellular differentiation.

Light Regulation of the Introduced Promoter Construct

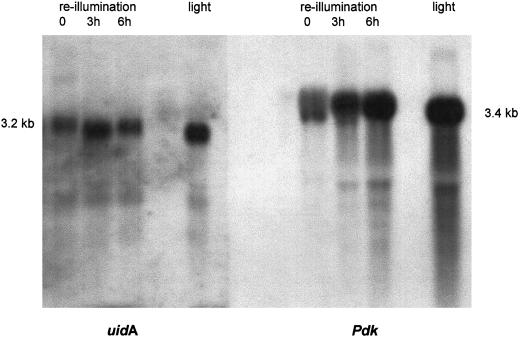

The 3.4-kb PPDK transcript in leaves of F. trinervia is positively light regulated (Rosche and Westhoff, 1995). The darkening of mature plants results in a significant decrease of the transcript levels, which increase again after illumination.

Because the GUS protein tends to be very stable (Jefferson et al., 1987), we measured transcript levels in the plants 217–1 and 217–3, which were kept in the dark for 3 d prior to reillumination for up to 6 h. Poly(A+) RNA was probed with the uidA gene and Pdk cDNA from F. trinervia. Results for the plant 217–3 are shown in Figure 6. The endogenous Pdk mRNA decreased to low levels in the dark and then rapidly increased within 6 h to levels similar to light-grown plants. The uidA mRNA transcribed from the introduced construct showed an increase with reillumination as well. However, this increase seems to be less pronounced than that of the Pdk transcript, possibly due to lower overall transcript levels of the uidA mRNA. Although we used probes of similar lengths and comparable labeling in three independent experiments, the signal strengths of the uidA mRNA were always lower compared with the Pdk transcript.

Figure 6.

Northern-blot analysis of plants left in the dark and reilluminated plants. The T0 plant 217–3 was left in the dark for 3 d and was subsequently reilluminated in the greenhouse. Leaves were harvested after 0, 3, and 6 h of reillumination, as well as from light-grown control plants. Five micrograms of poly(A+) RNA of each sample was loaded twice onto the same gel, generating two identical patterns. The gel was blotted and hybridized with labeled PCR products of the uidA gene and the Pdk cDNA of F. trinervia. The blots were hybridized a second time with a probe for actin to test for equal loadings.

To examine light induction in etiolated seedlings we germinated and grew T1 seeds either in the dark or in constant light. The seeds had been previously illuminated for 1 d to ensure germination. As shown in Table II, cotyledons grown in the light had severalfold greater GUS activity than those grown in the dark. After 10 d of growth in the dark, transfer to light gave a progressive 3-fold increase in GUS. Although we did not determine the extent of leaf-cell development in these seedlings, we conclude that light induces the expression of the reporter gene in both seedlings and in mature plants.

Table II.

Light induction of GUS activity in seedlings

| T1 Line | Light/Dark Conditions | GUS Activity |

|---|---|---|

| nmol MUa min−1 mg−1 protein | ||

| 217-5 | 10 d of dark | 8.2 |

| 12 d of light | 26.6 | |

| 217-3 | 7 d of dark | 6.9 |

| 7 d of light | 16.7 | |

| 10 d of light | ||

| +3 d of dark | 8.5 | |

| 27-3 | 10 d of dark | 8.9 |

| +0.5 h of light | 8.5 | |

| +1 h of light | 8.0 | |

| +1.5 h of light | 9.5 | |

| +2 h of light | 11.0 | |

| +2.5 h of light | 11.4 | |

| +12 h of light | 27.2 |

GUS activity was measured in cotyledons from individual seedlings. Seedlings were grown for the indicated number of days in either continuous dark or light, or dark-grown seedlings were transferred to continuous light for the indicated number of hours.

MU, Methylumbelliferyl.

DISCUSSION

The genes coding for some C4 enzymes are members of small gene families. Gene duplications created additional gene copies, which subsequently gained the necessary cis-acting regulatory elements that confer high-level, light-regulated, and cell-specific expression that is necessary for the assembly of the C4 pathway. This mechanism preserved the ancestral genes coding for nonphotosynthetic isoforms, which are found in C4 species and which are expressed at levels similar to C3 species. Examples are the gene families coding for PEPC and ME. The C3 species F. pringlei and the C4 species F. trinervia have similar numbers of genes coding for PEPC (Hermans and Westhoff, 1990, 1992). Gene-specific probes identified orthologous Ppc genes in the C3 species that are very similar in sequence to the PpcA genes encoding the C4 isoform in the C4 species. In the C3 species these PpcA genes are expressed at low levels in most organs. Stockhaus et al. (1997) showed that 5′ sequences from the PpcA1 gene of F. pringlei (C3) also directed low-level uidA gene expression in transgenic F. bidentis (C4) plants, whereas 5′ sequences from the F. trinervia (C4) gene directed high level expression. This result provides evidence for the role of new cis-acting sequences in the C4 species.

A similar analysis identified two genes encoding chloroplast-localized ME isoforms in Flaveria (Marshall et al., 1996). One gene, Me1, encodes the C4 form in the C4 species. Me1 is present in the C3 species but is expressed at low levels. The second gene, Me2, is expressed at very low levels in all species.

The Pdk gene does not fit this simple evolutionary story. In the genus Flaveria it is present as a single-copy gene, which performs both the function of the ancestral nonphotosynthetic gene and the MC-specific C4 gene. We have used a transformation approach to determine the relationship of the cis-acting DNA sequences controlling the different programs of expression of the Pdk gene from F. trinervia, a C4 species. Rosche and Westhoff (1995) previously showed that the 3.4-kb transcript of this gene could be detected not only in MC, where it encodes the enzyme used in the C4 pathway, but also at much lower levels in BSC and in stems. Our data show that 1.5 kb of DNA upstream of the ATG directs similar expression of the uidA reporter gene. Most GUS activity was located in MC, with lower levels in BSC and in stems (Figs. 3 and 5). Although the 3.4-kb transcript was not detected in roots, extremely low amounts of GUS were found in roots, which may be due to the greater sensitivity of the GUS fluorescence assay compared with RNA northern blots.

We tried to localize the GUS activity in stem sections by GUS staining and found most of the indigo in the vascular bundles. However, the level of the actual GUS activity in these cells remains to be investigated. In leaves the GUS product accumulated in cells of the veins, although the cell-separation data clearly show a preferred expression in MC. Taken together, it seems that GUS-expression studies based on histochemical data alone can lead to questionable results. The high stability of the GUS product enhances the accumulation in cells with low promoter activity. In addition, diffusion of the initial GUS product via the frequent and large plasmodesmata that occur between the MC and BSC of C4 plants (Robinson-Beers and Evert, 1991) can lead to the precipitation of the insoluble end product in cells where the uidA gene is not expressed. The accumulation in veins indicates a preferred precipitation of the GUS product in this compartment. The histochemical analysis of the GUS expression driven by the Ppc promoter (Stockhaus et al., 1997) indicates that the problems mentioned above are not as evident when the promoter activity is strictly cell specific. The authors report the diffusion of the GUS product in BSC only after longer incubation periods. Our cell-separation data show low GUS activity in BSC, in accordance with the northern data obtained previously for the endogenous Pdk gene (Rosche and Westhoff, 1995). The resulting GUS staining of these cells was not proportional to the actual GUS activity measured in the separated cells.

The high level expression of the Pdk gene in MC was also dependent on light and on the stage of leaf development. Here we show that the uidA transcript exhibited a similar response to light in transgenic F. bidentis plants (Fig. 6), indicating that the cis-element responsible for the light-regulated expression is present within the 1.5-kb promoter region. Although the transcripts of the endogenous Pdk gene and the introduced uidA construct in the investigated transplant were not quantified, the level of the GUS mRNA seemed to be significantly lower. Reasons for these differences could be different stabilities of the transcripts or position effects within the genome.

In mature leaves the measured GUS activity was found to be greatest in the basal region of the leaf, where most of the cell divisions occur. The activity decreased toward the tip of the leaf, where the cellular development is most advanced. In contrast, the GUS staining of very young leaves indicated a good correlation between the intensity of the color and the cell differentiation. The histochemical results are similar to those found for the ppcA promoter/uidA construct in F. bidentis transplants (Stockhaus et al., 1997). Thus, these C4 promoters seem to be active in developing leaves in correlation with the differentiation of MC and BSC. In mature leaves, however, the oldest regions show the lowest GUS activity.

We conclude that DNA sequences sufficient for expression of the C4 form of PPDK in MC and for expression of the chloroplast form in other cells and organs are co-located within the same 5′ region of the F. trinervia Pdk gene. In evolutionary terms, the C4 cis-acting sequences appear to have been added to a promoter that was active in a wide range of cells without significantly altering the activity of that promoter. Our next step will be to identify the cis-acting sequences controlling both expression programs and determine their structural and functional relationships to one another. The strong correlation between GUS activity directed by 5′ sequences of the gene and the distribution of Pdk mRNA suggest that these cis-acting sequences control transcription. However, the inclusion of the 5′ untranslated region of the Pdk transcript in our reporter gene construct means that we cannot exclude the involvement of mRNA stability in gene regulation.

The dual-function maize Pdk gene has also been analyzed for cis-acting regulatory sequences. Transient expression assays in maize leaf protoplasts (Sheen, 1991) and in microprojectile-bombarded maize leaves (Matsuoka and Numazawa, 1991) identified sequences upstream of the transcription initiation site, which are necessary for high level leaf expression. These analyses were not able to determine whether the promoter constructs were active at lower levels in other cells and organs. Matsuoka et al. (1993) were able to show that the promoter for the chloroplast form of maize PPDK was specifically expressed in transgenic rice leaves and that this expression was at high levels, preferentially in MC. These data strongly suggest that the dual-function maize gene is equivalent to the single Flaveria Pdk gene and that the evolutionary origin of the maize gene may also have been from the addition of C4 regulatory elements to an ancestral gene. However, it is not evident if the chloroplast form of the maize gene is expressed in other cells and organs.

The F. bidentis transformation system has been used by Stockhaus et al. (1997) to look for regulatory sequences from the F. trinervia (C4) PpcA1 gene, which codes for the mesophyll-specific isoform of PEPC. 5′ Sequences, including the entire 5′ untranslated region, directed a pattern of GUS expression that was very similar to the distribution of PpcA mRNA. The authors draw similar conclusions to ours about the importance of 5′ cis-acting sequences in regulating, most likely through transcriptional control, the expression of a gene coding for a C4 enzyme. In contrast, Marshall et al. (1997) have found that 5′ and 3′ sequences from the Me1 gene of F. bidentis, which codes for the C4 isoform of ME, are required for high-level BSC expression of the uidA reporter gene in transgenic F. bidentis. They have not yet determined the level of this regulation or how 3′ sequences interact with 5′ sequences. 3′ Sequences have also been shown to be important in controlling BSC-specific expression of the maize RbcS-m3 gene (Viret et al., 1994), whereas Ramsperger et al. (1996) have presented evidence that translational regulation may be important in BSC specificity of both Rubisco subunits. Thus, there does not appear to be one single mechanism regulating the expression of genes coding for enzymes of the C4 pathway.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tony Agostino for advice concerning cell-separation methods; John Lunn for help with linear-regression analyses; and Brian Surin, Tony Ashton, and Paul Whitfeld for helpful comments about the manuscript.

Abbreviations:

- BSC

bundle-sheath cell(s)

- MC

mesophyll cell(s)

- ME

NADP-malic enzyme

- PEPC

PEP carboxylase

- PPDK

pyruvate Pi dikinase

- WLC

whole-leaf cell(s)

Footnotes

The isolation of the Pdk promoter was done in Düsseldorf, Germany, and was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft via Sonderforschungsbereicht 189. E.R. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

LITERATURE CITED

- Agostino A, Furbank RT, Hatch MD. Maximising photosynthetic activity and cell integrity in isolated bundle sheath cell strands from C4 species. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1989;16:279–290. [Google Scholar]

- An G. Development of plant promoter expression vectors and their use for analysis of differential activity of nopaline synthase promoter in transformed cells. Plant Physiol. 1986;81:86–91. doi: 10.1104/pp.81.1.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyagi K, Bassham JA. Pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase in wheat leaves. Plant Physiol. 1983;73:853–854. doi: 10.1104/pp.73.3.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyagi K, Bassham JA. Pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase mRNA organ specificity in wheat and maize. Plant Physiol. 1984a;76:278–280. doi: 10.1104/pp.76.1.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyagi K, Bassham JA. Pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase of C3 seeds and leaves as compared to the enzyme from maize. Plant Physiol. 1984b;75:387–392. doi: 10.1104/pp.75.2.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyagi K, Bassham JA. Synthesis and uptake of cytoplasmically synthesized pyruvate, Pi dikinase polypeptide by chloroplasts. Plant Physiol. 1985;78:661–664. doi: 10.1104/pp.78.4.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton AR, Burnell JN, Furbank RT, Jenkins CLD, Hatch MD. Enzymes of C4 photosynthesis. Methods Plant Biochem. 1990;3:39–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bruchhaus I, Tannich E. Primary structure of the pyruvate phosphate dikinase in Entamoeba histolytica. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;62:153–156. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90193-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitty JA, Furbank RT, Marshall JS, Chen Z, Taylor WC. Genetic transformation of the C4 plant, Flaveria bidentis. Plant J. 1994;6:949–956. [Google Scholar]

- Church GM, Gilbert W. Genomic sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1991–1995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards GE, Walker DA. C3, C4: Mechanism, and Cellular and Environmental Regulation, of Photosynthesis. Oxford, London: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Glackin CA, Grula JW. Organ-specific transcripts of different size and abundance derive from the same pyruvate, orthophosphate dikinase gene in maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3004–3008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.8.3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata S, Matsuoka M. Immunological studies on pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase in C3 plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 1987;28:635–641. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch MD. C4 photosynthesis: a unique blend of modified biochemistry, anatomy and ultrastructure. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;895:81–106. [Google Scholar]

- Hermans J, Westhoff P. Analysis of expression and evolutionary relationships of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase genes in Flaveria trinervia (C4) and F. pringlei (C3) Mol Gen Genet. 1990;224:459–468. doi: 10.1007/BF00262441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans J, Westhoff P. Homologous genes for the C4 isoform of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase in a C3- and a C4-Flaveria species. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;234:275–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00283848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höfer MU, Santore UJ, Westhoff P. Differential accumulation of the 10-, 16- and 23-kDa peripheral components of the water-splitting complex of photosystem II in mesophyll and bundle-sheath chloroplasts of the dicotyledonous C4 plant Flaveria trinervia (Spreng.) C. Mohr. Planta. 1992;186:304–312. doi: 10.1007/BF00196260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudspeth RL, Glackin CA, Bonner J, Grula JW. Genomic and cDNA clones for maize phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase and pyruvate, orthophosphate dikinase: expression of different gene-family members in leaves and roots. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:2884–2888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.9.2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen BJ, Gardner RC. Localized transient expression of GUS in leaf discs following co-cultivation with Agrobacterium. Plant Mol Biol. 1989;14:61–72. doi: 10.1007/BF00015655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson RA, Kavanagh TA, Bevan MW. GUS fusions: β-glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO J. 1987;6:3901–3907. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02730.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JS, Stubbs JD, Chitty JA, Surin B, Taylor WC. Expression of the C4 Me1 gene from Flaveria bidentis requires an interaction between 5′ and 3′ sequences. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1515–1525. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.9.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JS, Stubbs JD, Taylor WC. Two genes encode highly similar chloroplastic NADP-malic enzymes in Flaveria. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:1251–1261. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.4.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka M. Structure, genetic mapping, and expression of the gene for pyruvate, orthophosphate dikinase from maize. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:16772–16777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka M. The gene for pyruvate, orthophosphate dikinase in C4 plants—structure, regulation and evolution. Plant Cell Physiol. 1995;36:937–943. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a078864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka M, Numazawa T. Cis-acting elements in the pyruvate, orthophosphate dikinase gene in maize. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;228:143–152. doi: 10.1007/BF00282459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka M, Ozeki Y, Yamamoto N, Hirano H, Kano-Murakami Y, Tanaka Y. Primary structure of maize pyruvate, orthophosphate dikinase as deduced from cDNA sequence. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:11080–11083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka M, Tada Y, Fujimura T, Kano-Murakami Y. Tissue-specific light-regulated expression directed by the promoter of a C4 gene, maize pyruvate, orthophosphate dikinase, in a C3 plant, rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9586–9590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer AO, Kelly GJ, Latzko E. Pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase from the immature grains of cereal grasses. Plant Physiol. 1982;69:7–10. doi: 10.1104/pp.69.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore PD. Evolution of photosynthetic pathways in flowering plants. Nature. 1982;295:647–648. [Google Scholar]

- Pocalyko DJ, Carroll LJ, Martin BM, Babbitt PC, Cunaway-Mariano D. Analysis of sequence homologies in plant and bacterial pyruvate phosphate dikinase, enzyme I of the bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system and other PEP-utilizing enzymes. Identification of potential catalytic and regulatory motifs. Biochemistry. 1990;29:10757–10765. doi: 10.1021/bi00500a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell AM. Systematics of Flaveria (Flaveriinae-Asteraceae) Ann Mo Bot Gard. 1978;65:590–636. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsperger VC, Summers RG, Berry JO. Photosynthetic gene expression in meristems and during initial leaf development in a C4 dicotyledonous plant. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:999–1010. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.4.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson-Beers K, Evert RF. Ultrastructure of and plasmodesmatal frequency in mature leaves of sugarcane. Planta. 1991;184:291–306. doi: 10.1007/BF00195330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosche E, Streubel M, Westhoff P. Primary structure of the photosynthetic pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase of the C3 plant Flaveria pringlei and expression analysis of pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase sequences in C3, C3-C4 and C4 Flaveria species. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;26:763–769. doi: 10.1007/BF00013761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosche E, Westhoff P. Primary structure of pyruvate, orthophosphate dikinase in the dicotyledonous C4 plant Flaveria trinervia. FEBS Lett. 1990;273:116–121. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81064-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosche E, Westhoff P. Genomic structure and expression of the pyruvate, orthophosphate dikinase gene of the dicotyledonous C4 plant Flaveria trinervia (Asteraceae) Plant Mol Biol. 1995;29:663–678. doi: 10.1007/BF00041157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheen J. Molecular mechanisms underlying the differential expression of maize pyruvate, orthophosphate dikinase genes. Plant Cell. 1991;3:225–245. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.3.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M, Heldt HW. Control of photosynthetic sucrose synthesis by fructose-2,6-bisphosphate. Planta. 1985;164:179–188. doi: 10.1007/BF00396080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockhaus J, Schlue U, Koczor M, Chitty JA, Taylor WC, Westhoff P. The promoter of the gene encoding the C4 form of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase directs mesophyll specific expression in transgenic C4 Flaveria. Plant Cell. 1997;9:479–489. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.4.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viret J-F, Mabrouk Y, Bogorad L. Transcriptional photo-regulation of cell-type-preferred expression of maize rbcS-m3: 3′ and 5′ sequences are involved. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8577–8581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]