Abstract

Objectives

Salivary chromogranin A (CgA) levels and salivary flow rates were measured to evaluate the stress relief effect of laughter on the young and the elderly.

Methods

Thirty healthy volunteers (15 aged 20–25 years; 15 aged 62–83 years) performed a serial arithmetic task for 15 min and then watched a comedy video for 30 min. On a different day, as a control, they watched a non-humorous video after performing a task similar to the first one. Saliva samples were collected immediately before and after the arithmetic task, 30 min after completing the task (immediately after watching the film), and 30 min after watching the film (60 min after completing mental task). Salivary CgA levels were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Results

In the elderly group, salivary flow rates, which had declined by the end of the arithmetic task, were statistically significantly higher after watching the comedy video. In the young group, salivary CgA levels, which had increased by the end of the task, had statistically significantly declined after watching the comedy video. No such post-task changes were apparent in control results; in the young group, there was a statistically significant interprotocol difference in salivary CgA levels.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that laughter may relieve stress, particularly in the young people.

Keywords: Chromogranin A, Laughter, Salivary flow rates, Stress, The elderly

Introduction

Since ancient times, many observations of the effect of laughter have been taken as empirical evidence supporting the notion that laughter can have positive effects on human health. More recently, it has been possible to scientifically investigate the physiological changes associated with laughter. Several studies have reported elevated natural killer cell activity and reduced serum cortisol levels after watching comedy videos [1–4], suggesting that laughter relieves stress. These measurements, however, were made on blood samples. To the best of our knowledge, the effects of laughter on different age groups have not been studied. Consequently, we have investigated the effects of laughter on salivary chromogranin A (CgA) and salivary flow rates and whether age affects these effects.

Saliva collection is a convenient, noninvasive, and relatively nonstressful sampling method. It is possible to assay for CgA, an acidic glucoprotein that is released along with catecholamines from the adrenal medulla and the sympathetic nerve endings [5–7] and, according to a recent report, CgA is also produced by human submandibular glands and secreted into saliva [8]. Because salivary CgA reflects sympathetic activity, salivary CgA measurement is becoming an established means of evaluating stress [9, 10]. At the same time, since fibers of the parasympathetic nervous system also innervate the salivary glands and stimulate salivary flow rates [11], it has also been suggested that salivary flow rates may reflect stress reactions [12, 13].

Materials and methods

This study was conducted as a part of the project “Promoting mental health and longevity for people in Fukui Prefecture”. After receiving the approval of the institute’s review board, we enrolled 15 young (aged 20–25 years) and 15 elderly (aged 62–83 years) healthy volunteers residing in Fukui Prefecture, Japan. Each group comprised seven males and eight females. None reported the regular use of any medication known to affect saliva secretion. Prior to the study, written informed consent was received from each participant.

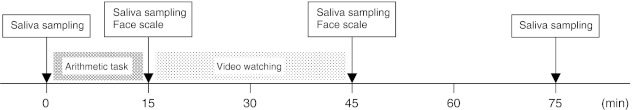

On different days, the study participants performed a “stressing” mental activity, immediately followed by watching either a film/TV comedy show (test situation) or a non-humorous video (landscape scenes; control situation) for 30 min. The comedy shows were selected for their appropriateness/popularity for each age group. Before the video was shown, the participants performed the Uchida–Kraepelin test [14, 15], which is a serial arithmetic task, for 15 min. Several psychophysiological studies have used this test as a mental stressor [16–18]. As Fig. 1 shows, saliva samples were collected immediately before and after the arithmetic task, 30 min after completion of the test (immediately after watching the film), and 30 min after watching the film (60 min after completing stressing mental test). The comedy video protocol was conducted first, followed just 1 week later by the control protocol. To minimize the effects of circadian variation, the protocols took place in the afternoon [19].

Fig. 1.

Study protocol

Saliva samples were collected using the Salivette system (Sarstedt Co, Nümbrecht, Germany). In this system, subjects keep cotton wads in their mouths (for 2 min) and saliva samples are later extracted from the cotton wads by centrifugation (at 3,000 rpm for 15 min). Samples are then stored at −80 °C until assayed. Salivary CgA levels were evaluated using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) following a previously described method [20].

Prior to beginning the experiment, the 30 participants were asked to complete a written questionnaire that enabled the following eight lifestyle items to be evaluated according to the Health Practice Index (HPI) [21]: smoking habits; drinking habits; daily consumption of breakfast; appropriate daily duration of sleep and work; regular physical activity; appropriate levels of subjective stress; nutritionally balanced diet. In addition, mood status immediately before and after watching the video was measured using a face scale, which comprised five different facial expressions, with scoring from 0 (very unpleasant) to 4 (very pleasant). The reliability and validity of this scale have been confirmed [22].

Values were normalized as percentages of the baseline (before the arithmetic task). Student’s paired t test was performed to detect interprotocol differences, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures were performed to detect time-related differences. Bonferroni’s test was used for multiple comparisons. Chi-square testing was performed to compare the responses to each HPI item between age or gender groups. Scores for the face scale were analyzed using the non-parametric Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks test. Values were considered to be significantly different at p < 0.05.

Results

Chi-square results revealed a significant age difference for daily consumption of breakfast (p < 0.01) (Table 1), with more of the elderly group reporting that they eat breakfast every morning. No such difference was apparent for other HPI items. In addition, in neither the young nor the elderly group were significant gender differences apparent for any particular HPI items.

Table 1.

Percentage of respondents with high scores for preferable lifestyle habits

| Positive lifestyle factors | Young group (%) (n = 15) | Elderly group (%) (n = 15) | Chi-square | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking habits (not smoking) | 93.3 | 100 | 1.03 | 1.000 |

| Drinking habits (not consuming alcohol daily) | 100 | 86.7 | 2.14 | 0.483 |

| Consumption of breakfast (daily) | 46.7 | 100 | 10.91 | 0.002 |

| Duration of sleep (7–8 h per night) | 33.3 | 60.0 | 2.14 | 0.272 |

| Duration of work (<10 h per day) | 66.7 | 100 | 3.02 | 0.135 |

| Physical activity (exercising twice a week or more) | 73.3 | 83.3 | 0.39 | 0.662 |

| Subjective stress (keeping stress levels low) | 80.0 | 100 | 3.33 | 0.224 |

| Nutritional balance (eating a nutritionally balanced diet) | 6.7 | 26.7 | 2.16 | 0.330 |

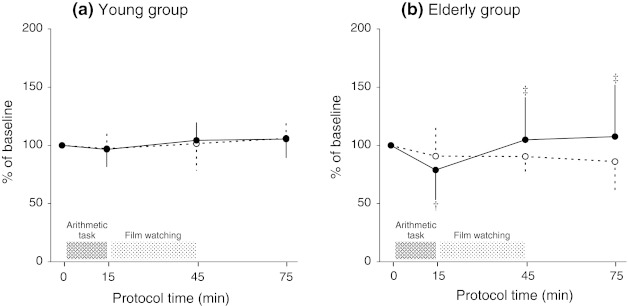

People in the elderly group had statistically significantly lower salivary flow rates immediately after performing the arithmetic task (protocol 15 min) than before the task (protocol 0 min) (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2). In addition, statistically significantly higher salivary flow rates were detected at 30 min (protocol 45 min) and 60 min (protocol 75 min) after the task compared to immediately after the task (p < 0.05). In contrast, the elderly group showed no such change during the control protocol. At 30 min or 60 min after the task, however, there was no statistically significant difference in normalized salivary flow rates between the comedy video protocol and the control protocol. In the young group, no statistically significant changes in salivary flow rates were detected during either the comedy video protocol or the control protocol.

Fig. 2.

Mean values [± standard deviation (SD)] normalized as percentage of the baseline (0 min) value for salivary flow rates during the comic film protocol (filled circles, solid line, n = 15) and the control protocol (open circles, dashed line, n = 15). Statistically significant difference compared with †0 min and ‡15 min; p < 0.05 [repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferroni’s test]

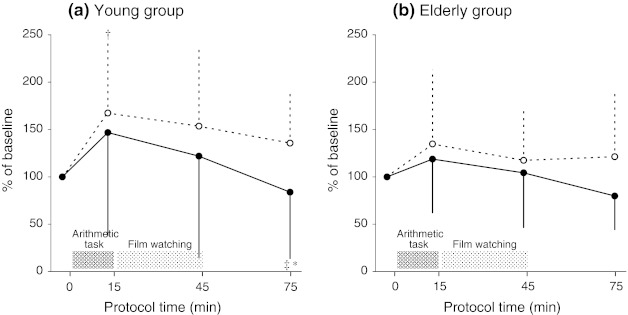

In the comedy video protocol, levels of salivary CgA were statistically significantly lower in samples taken from the young group at 60 min after completion of the mental task than in those taken immediately after the task (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3). At 60 min after the task, normalized salivary CgA levels were statistically significantly lower in the comedy video protocol than in the control protocol (p < 0.05). In comparison, during the control protocol, the young group showed statistically significantly higher CgA levels immediately after the task compared to before the task (p < 0.05). In the elderly group, no statistically significant changes in salivary CgA levels were detected during either the comedy video protocol or the control protocol.

Fig. 3.

Mean values (±SD) normalized as percentage of the baseline (0 min) value for salivary chromogranin A (CgA) levels in samples taken during the comic film protocol (open circles, solid line, n = 15) and in control samples (filled circles, dashed line, n = 15). †, ‡Statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) compared with 0 and 15 min, respectively (repeated measures ANOVA and Bonferroni’s test). *Statistically significantly different (p < 0.05) from the control protocol (Student’s paired t test)

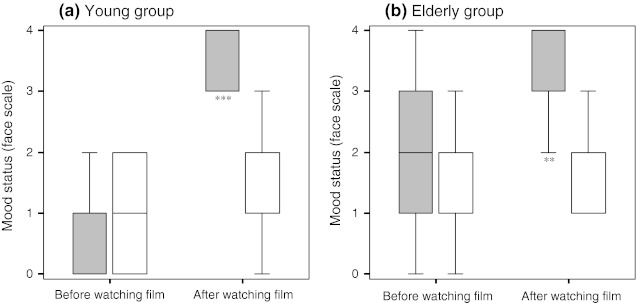

Feelings of pleasantness, evaluated using a face scale, increased significantly in both age groups after watching the comedy video (Fig. 4). Before and after watching the control film, there was no such change in either group.

Fig. 4.

Changes in mood status after watching the comic film (gray box, n = 15) and the non-humorous control film (non-shaded box, n = 15). Line inside of the box-plot Median value, lower, upper regions of the box lower, upper quartiles, respectively, lower, upper horizontal lines outside of the box smallest and largest observations, respectively. **, ***Statistically significantly different from “before watching film” at p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks test)

No gender differences in salivary parameters or mood status were apparent for either the young or the elderly group.

Discussion

The major findings of this study are (1) laughter, particularly in young people, may relieve stress and (2) stress reactions appear to be better reflected in young adults by salivary CgA levels and in elderly people by salivary flow rates.

Changes in salivary flow rates were more pronounced in the elderly group than in the young group. During the comedy video protocol, there was a significant decrease in salivary flow rates after the arithmetic task, which may have resulted from tension and uneasy emotional states [12]. Another study has also reported that a computer task caused a greater change in the salivary flow rates in elderly women than in young women [23]. Such findings suggest that salivary flow rates in elderly people may more sensitively reflect stress reactions. There was also a significant difference in eating breakfast each morning between the two age groups. In a previous study, we found that, probably due to increased frequency of mastication, the responsivity of salivary secretion is enhanced in individuals who eat breakfast every morning [24]. This finding may be relevant to the present findings. During the control protocol, however, no change was apparent in the elderly group, possibly due to the experimental design. The comedy video protocol was conducted first, followed just 1 week later by the control protocol. In the second protocol, therefore, familiarity may have decreased the tension and uneasiness experienced in the previous protocol. This problem should be resolved in future studies. There was a statistically significant increase, however, in salivary flow rates after watching the comedy video, while there was no such change after watching the control film. These findings suggest that laughter does relieve stress. This hypothesis is supported by improvements in self-reported mood status after the comedy video. Even so, at each sampling point after the participants had watched the video, no interprotocol difference in salivary flow rates was apparent. To conclusively establish our hypothesis, further studies are required.

In a previous study of university students aimed at investigating the subjective perception of stress, we found statistically significantly increased levels of salivary CgA after the same type of serial arithmetic task [25]. In the present study, we also found a statistically significant increase in salivary CgA levels in samples taken from the young group after the arithmetic task during the control protocol. On the other hand, a lack of significant increase in CgA levels after the task in the young group during the comedy video protocol may also be associated with the repetition effect: at the start of the first protocol, they may have felt more stress. Actually, salivary CgA levels at baseline were statistically significantly higher in the first protocol (p < 0.05) (Table 2). Even so, there was a significant decrease in salivary CgA levels after the comedy video had been watched; in contrast, after watching the control film, there was no such change. Furthermore, in samples taken after the participants had watched the video, we detected a statistically significant interprotocol difference in normalized salivary CgA levels. These findings suggest that laughter does indeed relieve stress. This hypothesis is supported by improvements in self-reported mood status after the comedy video. Incidentally, the elderly group showed similar trends to the young group, but these were not statistically significant, possibly suggesting a decreased CgA reactivity in elderly people. Since sympathetic activity is augmented with aging [26], salivary CgA in the elderly group may normally be maintained at high levels. A previous study has also reported, both before and during endoscopy, that salivary CgA levels were significantly higher in an elderly group than in a young group and that after endoscope insertion, decreases were statistically significantly larger in the young group [27].

Table 2.

Mean values for salivary flow rates and salivary chromogranin A levels at baseline

| Indicators | Young group (n = 15) | Elderly group (n = 15) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comic film protocol | Control protocol | p valuea | Comic film protocol | Control protocol | p valuea | |

| Salivary flow rates (mL/min) | 1.14 ± 0.22 | 1.10 ± 0.23 | 0.323 | 0.78 ± 0.31 | 0.94 ± 0.43 | 0.091 |

| Salivary chromogranin A levels (pmol/mL) | 6.42 ± 4.09 | 3.10 ± 1.56 | 0.015 | 6.40 ± 3.19 | 8.26 ± 3.42 | 0.084 |

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation

aStudent’s paired t test

This research has several limitations. First, as mentioned in this discussion, there was the methodological problem. The order of the experiment should have been randomized to cancel possible sequential effects. Second, the sample size was too small to provide conclusive results. Further examination of larger populations is required. Furthermore, laughter in our study was unidirectional and passive. It would also be interesting to investigate the effects of bidirectional and active laughter, such as that often occurring in conversation with others.

Acknowledgments

We thank students of Fukui Prefectural University and University of Fukui, and members of Shiromachi Senior Club and Ladies Club in Maruoka, Sakai City for participating in this study.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Bennett MP, Zeller JM, Rosenberg L, McCann J. The effect of mirthful laughter on stress and natural killer cell activity. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9:38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berk LS, Felten DL, Tan SA, Bittman BB, Westengard J. Modulation of neuroimmune parameters during the eustress of humor-associated mirthful laughter. Altern Ther Health Med. 2001;7:62–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berk LS, Tan SA, Fry WF, Napier BJ, Lee JW, Hubbard RW, et al. Neuroendocrine and stress hormone changes during mirthful laughter. Am J Med Sci. 1989;298:390–396. doi: 10.1097/00000441-198912000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takahashi K, Iwase M, Yamashita K, Tatsumoto Y, Ue H, Kuratsune H, et al. The elevation of natural killer cell activity induced by laughter in a crossover designed study. Int J Mol Med. 2001;8:645–650. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.8.6.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith AD, Winkler H. Purification and properties of an acidic protein from chromaffin granules of bovine adrenal medulla. Biochem J. 1967;103:483–492. doi: 10.1042/bj1030483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith WJ, Kirshner N. A specific soluble protein from the catecholamine storage vesicles of bovine adrenal medulla. Mol Pharmacol. 1967;3:52–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winkler H, Fischer-Colbrie R. The chromogranins A and B: the first 25 years and future perspectives. Neuroscience. 1992;49:497–528. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90222-N. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saruta J, Tsukinoki K, Sasaguri K, Ishii H, Yasuda M, Osamura YR, et al. Expression and localization of chromogranin A gene and protein in human submandibular gland. Cells Tissues Organs. 2005;180:237–244. doi: 10.1159/000088939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakane H, Asami O, Yamada Y, Harada T, Matsui N, Kanno T, et al. Salivary chromogranin A as an index of psychosomatic stress response. Biomed Res. 1998;19:401–406. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakane H, Asami O, Yamada Y, Ohira H. Effect of negative air ions on computer operation, anxiety, and salivary chromogranin A-like immunoreactivity. Int J Psychophysiol. 2002;46:85–89. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8760(02)00067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baum BJ. Principles of saliva secretion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;694:17–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb18338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gemba H, Teranaka A, Takemura K. Influences of emotion upon parotid secretion in human. Neurosci Lett. 1996;211:159–162. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12741-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Queiroz CS, Hayacibara MF, Tabchoury CP, Marcondes FK, Cury JA. Relationship between stressful situations, salivary flow rate and oral volatile sulfur-containing compounds. Eur J Oral Sci. 2002;110:337–340. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2002.21320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uchida Y. A manual of the Uchida–Kraepelin psychodiagnostic test. Tokyo: Psychotechnological Institute; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuraishi S, Kato M, Tsujioka B. Development of the Uchida–Kraepelin psychodiagnostic test in Japan. Psychologia. 1957;1:104–109. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oishi K, Kamimura M, Nigorikawa T, Nakamiya T, Williams RE, Horvath SM. Individual differences in physiological responses and type A behavior pattern. Appl Human Sci. 1999;18:101–108. doi: 10.2114/jpa.18.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sumiyoshi T, Yotsutsuji T, Kurachi M, Itoh H, Kurokawa K, Saitoh O. Effect of mental stress on plasma homovanillic acid in healthy human subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;19:70–73. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yasumasu T, Reyes del Paso GA, Takahara K, Nakashima Y. Reduced baroreflex cardiac sensitivity predicts increased cognitive performance. Psychophysiology. 2006;43:41–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2006.00377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Den R, Toda M, Nagasawa S, Kitamura K, Morimoto K. Circadian rhythm of human salivary chromogranin A. Biomed Res. 2007;28:57–60. doi: 10.2220/biomedres.28.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagasawa S, Nishikawa Y, Jun L, Futai Y, Kanno T, Iguchi K, et al. Simple enzyme immunoassay for the measurement of immunoreactive chromogranin A in human plasma, urine and saliva. Biomed Res. 1998;19:407–410. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morimoto K. Lifestyle and health. Jpn J Hyg. 2000;54:572–591. doi: 10.1265/jjh.54.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lorish CD, Maisiak R. The face scale: a brief, nonverbal method for assessing patient mood. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:906–909. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bakke M, Tuxen A, Thomsen CE, Bardow A, Alkjær T, Jensen BR. Salivary cortisol level, salivary flow rate, and masticatory muscle activity in response to acute mental stress: a comparison between aged and young women. Gerontology. 2004;50:383–392. doi: 10.1159/000080176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toda M, Morimoto K, Fukuda S, Hayakawa K. Lifestyle, mental health status and salivary secretion rates. Environ Health Prev Med. 2002;6:260–263. doi: 10.1007/BF02897979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toda M, Morimoto K. Effect of lavender aroma on salivary endocrinological stress markers. Arch Oral Biol. 2008;53:964–968. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Esler M, Lambert G, Kaye D, Rumantir M, Hastings J, Seals DR. Influence of ageing on the sympathetic nervous system and adrenal medulla at rest and during stress. Biogerontology. 2002;3:45–49. doi: 10.1023/A:1015203328878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujimoto S, Nomura M, Niki M, Motoba H, Ieishi K, Mori T, et al. Evaluation of stress reactions during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in elderly patients: assessment of mental stress using chromogranin A. J Med Invest. 2007;54:140–145. doi: 10.2152/jmi.54.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]