Abstract

Although socioemotional competencies have been identified as key components of youths’ positive development, most studies on empathy are cross-sectional, and research on the role of the family has focused almost exclusively on parental socialization. This study examined the developmental course of empathy from age 7 to 14 and the within-person associations between sibling warmth and conflict and youths’ empathy. On three occasions across 2 years, mothers, fathers, and the two eldest siblings from 201 White, working- and middle-class families provided questionnaire data. Multilevel models revealed that, controlling for youths’ pubertal status and parental education, girls’ empathy increased during the transition to adolescence and then leveled off, but boys’ lower levels of empathy remained relatively unchanged. Moreover, controlling for parental responsiveness and marital love, at times when firstborns and second-borns reported more sibling warmth and less sibling conflict than usual, they also reported more empathy than usual. The within-person association between sibling warmth and empathy also became stronger over time. Findings highlight gender differences in empathy development and the unique role of siblings in shaping each other’s socioemotional characteristics during adolescence.

Keywords: empathy development, gender differentiation, family systems, sibling relationships, multilevel modeling

Recent research has highlighted socioemotional competencies, such as emotion regulation, perspective taking, and social awareness, as key ingredients for youths’ positive development (Spinrad, & Eisenberg, 2009). The present study focused on empathy, the tendency to identify with and vicariously experience another’s feelings (Eisenberg, 2005). Although there is evidence that empathy continues to change through adolescence and adulthood (Grühn, Rebucal, Diehl, Lumley, & Labouvie-Vief, 2008), the majority of empathy research has been cross-sectional and conducted with young children. Given that empathy is a gendered quality (Rose & Rudolph, 2006), our first aim was to chart the developmental course of empathy from age 7 to 14 and to test whether the trajectory differed for girls and boys.

Numerous studies have identified the family as a primary source of socialization for youths’ socioemotional development, including empathy (Eisenberg, Morris, McDaniel, & Spinrad, 2009). Most research, however, has focused on the role of parents and overlooked other family members. In childhood, older sisters and brothers act as socialization agents for their younger siblings’ social and cognitive development (Dunn, 2002). The non-elective, complementary nature of sibling relationships creates a unique context in which children can learn about perspective taking and emotionally intense exchanges (Katz, Kramer, & Gottman, 1992), but these dynamics have not been studied much in adolescents. Our second aim was to address this gap in the family socialization literature by testing the within-person associations between sibling warmth and conflict and youths’ empathy and examining the roles of birth order and chronological age in these associations.

Empathy Development in Adolescence

Individuals experience empathy when they understand another’s thoughts or feelings and have an emotional response that mirrors that of the other (Eisenberg, 2005). Empathy is important, because it is often a precursor of and motivation for prosocial action (Eisenberg et al., 2009; Hoffman, 2001): Youths who demonstrate empathy are more likely to behave in prosocial ways, such as helping, sharing, and volunteering their time (Spinrad, & Eisenberg, 2009).

Empathy is grounded in increasingly complex cognitive skills, including putting oneself in another’s situation and being able to imagine others’ emotional states, and it continues to change throughout the lifespan (Grühn et al., 2009). Although most research has focused on empathy development in young children, the cognitive and social advances of adolescence have implications for empathy development. For example, brain regions that are involved in social cognitive processing undergo major changes during adolescence, and changes in these cortical and subcortical areas are associated with adolescents’ increasing ability to infer mental states and take another’s perspective (Decety, 2010). The complex social worlds of adolescents also create new opportunities for empathic understanding between friends, romantic partners, and peers (Eisenberg et al., 2009). Therefore, one would expect youths to show a general increase in empathy across adolescence. It is important to note that empathy is a gendered quality, with girls generally exhibiting more sensitivity to others’ feelings and emotions than boys (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Further, according to gender intensification theory, at the transition to adolescence, youths face increased socialization pressure to conform to traditional gender roles (Galambos, Berenbaum, & McHale, 2009). Therefore, one would also expect girls to have both higher levels of and more pronounced increases in empathy than boys during adolescence.

Findings on age-graded differences in empathy among adolescents are mixed, however. Although some cross-sectional studies indicate that older adolescents report higher levels of empathy than younger adolescents (Strayer & Roberts, 1997; Tonks, Williams, Frampton, Yates, & Slater, 2007), others suggest that empathy does not differ across age groups (Adams, 1983; Karniol, Gabay, Ochion, & Harari, 1998). There is also cross-sectional evidence for a decrease in empathy for boys between ages 8 and 15 (Saklofske & Eysenck, 1983) and an increase in empathy for girls between ages 13 and 16 (Olweus & Endersen, 1998). Longitudinal data yield similarly inconsistent results. In a 3-wave, longitudinal study, Davis and Franzoi (1991) documented a linear increase in empathy from age 14 to 18. In a 6-wave, longitudinal study of 26 youths, Eisenberg, Cumberland, Guthrie, Murphy, and Shepard (2005) found that, although perspective taking showed a linear increase from age 15 to 26, sympathy did not change over time. In a 2-wave, longitudinal study of Spanish youths, Mestre, Samper, Frías, and Tur (2009) found that girls’ empathy increased at a faster rate than did boys’ from age 13 to 14. Taken together, these findings suggest somewhat conflicting patterns of change across adolescence for girls and boys.

Sibling Relationships and Empathy

Previous research has identified the family as a key context for children’s social, cognitive, and emotional development, but the vast majority has focused on parenting and parent-child relationships (Eisenberg et al., 2009; Hoffman, 2001). Parents may actively encourage their child’s empathy, such as by discussing emotional responses when the child experiences distress or rewarding the child for caring and helping behaviors (Krevans & Gibbs, 1996). Experiences with a supportive and sensitive parent also may help promote empathy by enhancing children’s sense of connection to others and recognition of the value of other individuals (Staub, 1992), or by providing a role model for empathic behavior. Expanding on research on parental influences, we explored the role of another fundamental family relationship – the sibling relationship – and tested the links between sibling warmth and conflict and youths’ empathy across the transition to adolescence.

Although parents are a primary source of socialization, sibling interactions afford unique opportunities for children to learn about their own and others’ affective responses and emotions (Dunn, 1998). For many children, a sister or brother is the first person with whom they share secrets, argue, and negotiate. Unlike parent-child relationships, in which the roles of “parent” and “child” are complementary and parents often serve as instructors and a source of guidance, sibling relationships can be peer-like, characterized by more reciprocal social exchanges. In contrast to peer relationships, however, sibling relationships are non-elective and thus can be taken for granted, and because siblings spend substantial amounts of time together, often without adult supervision, they must learn to avoid or manage conflict (Katz et al., 1992). Their constant companionship, shared history of family experiences, and sometimes competing interests and needs make for emotionally intense relationships, or a “love-hate” dynamic (Dunn, 2002). As such, sibling relationships constitute a distinct component of the family context, one in which youths can learn and practice a range of social competencies, including understanding another’s emotional state and point of view (Dunn, 1998; Harris, 1994).

Research with young children has shown that siblings serve as socialization agents for each other’s socioemotional development (Downey & Condron, 2004; Stormshak, Bellanti, & Bierman, 1996). When they are as young as two years old, children display behaviors designed to provoke or upset a sibling, behaviors that require a sophisticated understanding of the sibling’s point of view (Dunn & Munn, 1985). By the preschool years and in middle childhood, children who have warm, cooperative sibling relationships are more socially competent and better able to label emotions and take others’ perspectives (Azmitia & Hesser, 1993; Dunn, Brown, Slomkowski, Tesla, & Youngblade, 1991; Howe & Ross, 1990). Some studies also indicate that moderate levels of sibling conflict may teach children about compromise, turn-taking, and problem solving (Stormshak et al., 1996). Others further suggest that it is how children work through sibling conflict, rather than the overall level of conflict, that has positive implications for emotional understanding (Katz et al., 1992; Ross, Ross, Stein, & Trabasso, 2006). Because older siblings tend to be more advanced than younger siblings in their socioemotional development, especially during early childhood (East, 2009), most studies frame their analyses to examine older siblings’ influences on their younger siblings. Younger siblings’ influences on their older sisters and brothers are rarely explored.

Another question that remains underexplored is whether siblings continue to have an impact on empathy in adolescence, when relationships with peers and others outside the family become increasingly important. There are a number of reasons to expect that the answer is yes. First, siblings remain a salient part of adolescents’ social environments (East, 2009). Second, the dramatic biological and social changes during adolescence that are thought to contribute to empathy development may also represent new opportunities for siblings to shape each other’s empathy. For young adolescents with an emerging interest in forging deeper and more intimate friendships, a close bond with a sister or brother might be a place to gain a better understanding of emotions and reciprocity in supportive exchanges (Howe, Aquan-Assee, Bukowski, Lehoux, & Rinaldi, 2001). A relationship characterized by hostility and conflict might discourage compassion and perspective taking (Howe et al., 2001), although it might also serve as a learning opportunity and motivation for adolescents to develop interpersonal skills that can be applied in other relationships (Katz et al., 1992). Few have studied the reverse direction of effect, but it is likely that these links are bidirectional: Youths who are more empathic may be more appealing social partners, and thus more likely to forge positive relationships with their sisters and brothers.

The literature on sibling influences on empathy and other socioemotional domains in adolescence is less developed than the work with young children. Howe at el. (2001) found that, when presented with a hypothetical interpersonal problem, young adolescents who had warm relationships with their siblings were more likely to generate specific solutions to the problem. The authors argued that a close sibling relationship provides youths with the opportunity to gain insights into others’ internal states, which in turn promotes their social and problem solving abilities. Using the first wave of data from the same dataset as the current study, Tucker, Updegraff, McHale, and Crouter (1999) showed that sibling warmth was associated with higher levels of empathy for second-born siblings, but not for the young adolescent firstborn siblings. However, this analysis was conducted separately for each sibling and did not formally test for birth order differences. The cross-sectional design also limited its ability to capture longitudinal and within-person changes in youths’ empathy. With respect to the role of sibling conflict, some have showed that sibling disputes may allow youths (aged 4-12 years) to practice persuasive negotiation and see another’s point of view (Ross et al., 2006). Few studies on this topic have been conducted with adolescents, however.

The Current Study

Although empathy is known to play a critical role in motivating youths’ prosocial behaviors (Eisenberg et al., 2009; Hoffman, 2001), surprisingly little research is available on how it changes as youths make the transition from childhood to adolescence or whether adolescent-aged siblings may contribute to each other’s empathy development. Using 3-wave, longitudinal data collected from firstborn and second-born siblings, the goals of the current study were to examine the developmental course of empathy from middle childhood to early adolescence and the within-person associations between sibling warmth and conflict and youths’ empathy.

To address our first goal, we used a multilevel modeling (MLM) strategy to chart the growth curve of empathy from age 7 to 14. Because brain areas that are involved in social cognitive processing undergo major changes during adolescence (Decety, 2010) and increasing interactions with peers present new opportunities for adolescents to practice their problem solving and interpersonal negotiation skills (Eisenberg et al., 2009), we hypothesized that empathy would generally increase across the transition to adolescence. Although there is no consensus on the role of gender in empathy development, based on theoretical predictions about gender socialization (Galambos et al., 2009; Rose & Rudolph, 2006) and the limited research available (Mestre et al., 2009; Olweus & Endersen, 1998), we expected that girls’ empathy would increase at a faster rate than boys’. When studying the effects of chronological age on youths’ socioemotional adjustment, an important confounding factor to consider is pubertal status: As reviewed by Hyde, Mezulis, and Abramson (2008), observable physical changes of puberty may differentially influence girls’ and boys’ self-perceptions and body image and invite new kinds of social attention, such as peer aggression and harassment, which may in turn affect adolescents’ feelings and emotions. Therefore, we included pubertal status as a time-varying control in the analyses to account for the potential confounding of physical changes. Moreover, given some evidence suggesting that youths’ perspective-taking and emotion understanding vary as a function of socioeconomic factors (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002), we controlled for parental education as a general index of family socioeconomic status.

With respect to our second goal, a MLM approach also allowed us to examine whether within-person changes in sibling relationship qualities were linked to within-person changes in youths’ empathy. By treating each sibling as her or his own control, a focus on within-person variation helps to eliminate stable, third variables as alternative explanations and provides for stronger inferences (Singer & Willett, 2003). Further, a MLM approach made it possible to include longitudinal data collected from two siblings in the same model and to test statistically whether the association between sibling relationship qualities and empathy varied by birth order and chronological age. Based on previous findings on parent-child and sibling relationships (Eisenberg et al., 2009; Katz et al., 1992), we expected that the overall levels of sibling warmth and conflict would be associated positively and negatively with youths’ empathy, respectively. Moreover, because older siblings are often socioemotionally more advanced than their younger siblings, we expected to find a stronger socialization effect for second-borns than for firstborns. Finally, given that biological and social changes during adolescence may provide new opportunities for siblings to shape each other’s socioemotional development (Howe et al., 2001), we expected that the associations between sibling relationship qualities and youths’ empathy would become stronger over time. Although the modeling of sibling relationship qualities as time-varying covariates partialed out the possible influence of stable individual differences, within-person associations still might be biased by other time-varying factors (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). In order to isolate the unique influence of sibling relationship qualities, we included two additional time-varying controls: Parental responsiveness and marital love. A family systems perspective posits that parent-child, marital, and sibling relationships are interconnected (Minuchin, 1985). At times when parents experience warmer relationships with their children than usual, for example, they also may be better able to promote children’s interpersonal skills (Eisenberg et al., 2009) and foster positive sibling relationships (Brody, 1998) than usual. Similarly, the marital relationship may shape the general emotional climate of the family and has the potential to create a spurious within-person association between sibling relationships and children’s socioemotional adjustment (Grych & Fincham, 1990). Therefore, we included parental responsiveness and marital love as time-varying controls in the analyses to rule out two important alternative explanations of our results.

Method

Participants

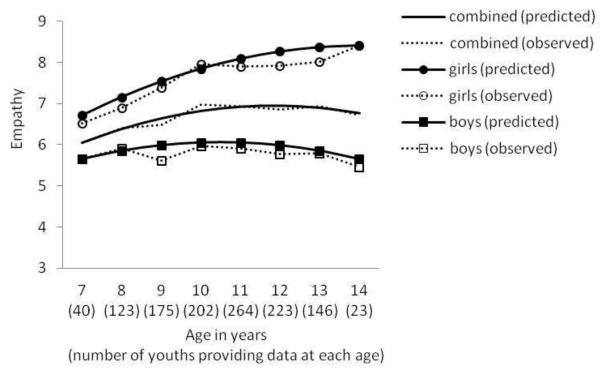

Data were drawn from the first three years (referred to as Years 1 through 3 hereafter) of a longitudinal study exploring family relationships and youth adjustment. Recruitment letters were sent through schools to families with 4th and 5th grade children in a northeastern state. Families were eligible if the parents were married, both parents were working, the firstborn sibling was in the 4th or 5th grade, and the second-born sibling was 1-4 years younger than the firstborn sibling. A total of 203 families participated. Two families that dropped out after Year 1 were deleted, and the analyses were based on the remaining 201 families that provided full data from Years 1 through 3. In Year 1, the average age was 10.87 years (SD = 0.54; range = 9.45-12.59) for firstborns and 8.26 years (SD = 0.93; range = 6.05-10.30) for second-borns. Because of the age difference between siblings and multiple waves of data collection, between 23 and 264 youths provided data at each chronological age from 7 (i.e., ages 6.5-7.5) to 14 (i.e., ages 13.5-14.5) years (see Figure 1). Sibling dyads were divided evenly among the four possible gender constellations (i.e., 50 older-sister-younger-sister dyads, 53 older-sister-younger-brother dyads, 50 older-brother-younger-sister dyads, and 48 older-brother-younger-brother dyads). There were no significant gender differences in age for firstborns (M = 10.81 years, SD = 0.56 for girls; M = 10.93 years, SD = 0.53 for boys) or for second-borns (M = 8.18 years, SD = 0.98 for girls; M = 8.34 years, SD = 0.88 for boys).

Figure 1.

Predicted (solid lines) and observed means (dotted lines) of empathy from middle childhood to early adolescence for girls and boys.

Reflecting the ethnic background of families from the state where the study was conducted (85% White; US Census Bureau, 2000), the sample included almost exclusively European American families living in small cities, towns, and rural communities. Moreover, reflecting the educational (> 80% of adults completed high school) and financial (median income = $55,714 for married-couple families) backgrounds of the targeted population, in Year 1, the average education level was 14.57 years (SD = 2.15; range = 12-20) for mothers and 14.67 years (SD = 2.43; range = 10-20) for fathers (where a score of 12 signified a high school graduate), and the median family income was $55,000 (SD = 28,613; range = 21,000-207,000). The wide ranges of parental education and family income levels, however, indicated that the sample was diverse in socioeconomic status and primarily included working- and middle-class families.

Procedures and Measures

In each year of the study, a team of interviewers conducted structured home interviews with mothers, fathers, and the two eldest siblings. Parents were interviewed by the project investigators and graduate assistants, and children were interviewed by undergraduate students who had previously enrolled in a tailored research method course and received 40 hours of training on youth development, survey designs, and interview techniques. Although the undergraduate interviewers had knowledge about the overall goal of the study, they were blind to the specific hypotheses concerning the inter-relationships among variables. After a general orientation and a review of human subject procedures, interviewers obtained informed consent and the family received a $100 honorarium for participating. Parents and youths then completed standardized questionnaires individually. For all measures, items were summed, such that a higher score indicated a higher level of the construct.

Empathy

Empathy was assessed using 10 items from the Index of Empathy for Children and Adolescents (Bryant, 1982). The original measure included 22 items. However, due to time constraints and concerns about participant fatigue, only 10 items that showed the highest item-total correlations in the pilot data were used in the study. In Years 1 through 3, youths rated their tendency to feel for other people and animals (e.g., “It makes me sad to see a girl who can’t find anyone to play with” and “I get upset when I see an animal being hurt”) on a dichotomous scale (0 = no; 1 = yes). Across the three time points, Cronbach’s alphas averaged .68 for firstborns and .60 for second-borns, comparable to those documented in earlier work that included participants of the same age (e.g., alphas = .68 for 4th graders and .54 for 1st graders; Bryant, 1982). Cross-time stability was evident, with stability coefficients (i.e., auto-correlations across time) averaging .65 for firstborns and .53 for second-borns.

Sibling warmth and conflict

Sibling warmth and conflict were assessed using the 8-item warmth subscale and 5-item conflict subscale from the Sibling Relationship Inventory (Stocker & McHale, 1992), respectively. In Years 1 through 3, youths rated their warm (e.g., “How often do you do nice things like helping or doing favors for your sibling?”) and conflictual (e.g., “How often do you feel mad or angry at your sibling?”) interactions with the target sibling on a 5-point scale (1 = hardly every; 5 = always). Cronbach’s alphas averaged .82, .77, .70, and .73 for firstborns’ and second-borns’ reports of warmth and firstborns’ and second-borns’ reports of conflict, respectively, again comparable to those documented in earlier work that included participants of the same age (e.g., Cronbach’s alphas = .82, .72, .74, and .71 for 4th and 5th graders’ and their younger siblings’ reports of warmth and 4th and 5th graders’ and their younger siblings’ reports of conflict, respectively; Stocker & McHale, 1992). Cross-time stability was also evident, with stability coefficients averaging .52, .51, .46, and .31 for firstborns’ and second-borns’ reports of warmth and firstborns’ and second-borns’ reports of conflict, respectively. Sibling warmth and conflict were modestly correlated (rs averaged −.19 for firstborns and −.22 for second-borns). The means and standard deviations of empathy and sibling warmth and conflict scores can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means (M) and Standard Deviations (SD) of Empathy, Sibling Warmth, and Sibling Conflict

| Year 1 |

Year 2 |

Year 3 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Empathy | |||

| Firstborn girls | 7.80 (1.37) | 7.81 (1.50) | 7.94 (1.47) |

| Firstborn boys | 6.07 (1.96) | 5.78 (1.93) | 5.86 (1.96) |

| Second-born girls | 7.04 (1.52) | 7.56 (1.51) | 8.02 (1.44) |

| Second-born boys | 5.73 (2.14) | 5.70 (2.00) | 5.74 (1.98) |

|

| |||

| Sibling warmth | |||

| Firstborn girls | 26.37 (5.20) | 25.94 (5.09) | 24.65 (5.08) |

| Firstborn boys | 24.02 (5.88) | 23.46 (5.87) | 22.41 (5.00) |

| Second-born girls | 25.12 (6.45) | 23.45 (5.50) | 22.62 (5.22) |

| Second-born boys | 22.61 (7.46) | 21.93 (6.34) | 20.77 (5.75) |

|

| |||

| Sibling conflict | |||

| Firstborn girls | 13.48 (3.09) | 13.93 (3.2 9) | 13.52 (3.53) |

| Firstborn boys | 13.94 (3.71) | 14.13 (3.17) | 13.50 (2.94) |

| Second-born girls | 13.53 (4.00) | 14.33 (4.12) | 14.12 (4.02) |

| Second-born boys | 14.50 (4.22) | 14.27 (4.57) | 14.05 (4.03) |

Parental responsiveness

Parental responsiveness was assessed using the 5-item responsiveness subscale from the Parenting Style Inventory (Darling & Toyokawa, 1997). In Years 1 through 3, youths separately rated their relationships with their mothers and fathers (e.g., “My mother/father spends time just talking to me”) on a 4-point scale (1 = really unlike; 4 = really like). The reliability of this measure has been established in other studies (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha = .74; Darling & Toyokawa, 1997). Because mothers’ and fathers’ responsiveness were moderately to highly correlated (rs averaged .50 for firstborns and .67 for second-borns), ratings for mothers and fathers were combined to create a general index of parental responsiveness. Cronbach’s alphas averaged .76 for firstborns and .74 for second-borns, and stability coefficients averaged .38 for firstborns and .35 for second-borns.

Marital love

Marital love was assessed using the 9-item marital love subscale from the Relationship Questionnaire (Braiker & Kelley, 1979). In Years 1 through 3, parents rated their commitment and closeness to their partners (e.g., “How close do you feel toward your partner?”) on a 9-point scale (1 = not at all; 9 = very much). The reliability of this measure has been established in other studies (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha = .86; MacDermid, Huston, & McHale, 1990). Because mothers’ and fathers’ reports of marital love were moderately correlated (rs averaged .49), their ratings were combined to create a general index of marital love. Cronbach’s alphas averaged .93, and stability coefficients averaged .79.

Pubertal status

Pubertal status was assessed using the 5-item Pubertal Development Scale (Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, 1988). In Years 1 through 3, mothers rated the development of secondary sexual characteristics (e.g., growth spurt, skin changes, growth of body hair) of their firstborns on a 4-point scale (1 = not begun; 2 = barely started; 3 = definitely underway; 4 = seems complete). Because the onset of puberty occurs at an average age of 10-11 years for girls and 11-12 years for boys (Lee, Guo, & Kulin, 2001), mothers only rated the pubertal development of their second-borns in Year 3, when they were about 10 years. Given that data were not available for second-borns in Years 1 and 2 and that the pervasive gender difference in the incidence of depressive and anxiety disorders disfavoring females is not evident until mid-puberty (Angold, Costello, & Worthman, 1998), a dichotomous variable was created to indicate whether or not the siblings had transitioned through mid-puberty at each time point. Girls’ pubertal transition was indexed using the date of menarche (0 = before menstruation started; 1 = after menstruation started), whereas boys’ pubertal transition was indexed using the mid-point of the measure (0 = equal or below 12.5; 1 = above 12.5). In Years 1, 2, and 3, 5% (n = 5), 21% (n = 22), and 70% (n = 72) of firstborn girls and 1% (n = 1), 18% (n = 18%), and 27% (n = 26) of firstborn boys had transitioned through mid-puberty, respectively. In Year 3, only 8% (n = 8) of second-born girls and no second-born boys had experienced the transition, and thus second-borns’ scores were coded as 0 in Years 1 and 2. A more detailed description and other psychometric properties of this dichotomized measure are reported elsewhere (Whiteman, McHale, & Crouter, 2007).

Results

Analytic Strategy

Given the nested (i.e., youths from the same family were repeatedly assessed) and unbalanced (i.e., youths were assessed at different ages) nature of the data, we used MLM as the analytic strategy (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). A series of three-level models (Level 1 = within-individual; Level 2 = between-individual; Level 3 = between-family) were estimated using the MIXED procedure in SAS Version 9.1. At Level 1, we included time-varying variables. We used youths’ ages as the metric of time, and included polynomial age terms (i.e., linear, quadratic) to describe the development of empathy over time. Youths’ ages were centered at age 11 (the approximate mean age across siblings and across time points). We also included the time-varying covariates (i.e., sibling warmth and conflict) and time-varying controls (i.e., pubertal transition, parental responsiveness, and marital love) at this level. To distinguish within-from between-person variations, each time-varying covariate was indicated by two variables: At Level 1, the covariate was indicated by a time-varying, group-mean centered (i.e., centered at each youth’s cross-time average) variable; at Level 2, the covariate was indicated by the grand-mean centered (i.e. centered at the sample mean), cross-time average. Whereas the Level 1 version of the covariate captured within-person variation and indicated how an individual deviated from her or his own cross-time average at each time point, the Level 2 version captured between-person variation and indicated how the individual’s cross-time average was different from the rest of the sample. Parental responsiveness and marital love were grand-mean centered at Level 1 without including the cross-time averages at Level 2, however, as we did not intend to distinguish the within- versus between-person effects of these control variables. Pubertal status already had been coded as 0 or 1 (whether or not youths had transitioned through mid-puberty), and thus no additional centering was needed. In addition to the cross-time averages of the covariates, at Level 2, we also included two other time-invariant variables that were different for the two siblings: Youths’ gender and birth order. The reference groups (i.e., coded as 0) for gender and birth order were girls (versus boys) and firstborns (versus second-borns), respectively. At Level 3, we included one time-invariant variable that was the same for the two siblings: Parental education (averaged across mothers and fathers) centered at 12 years (i.e., high school graduate). We conducted the analyses in three steps: First, we tested a general change model (Model 1) to examine the overall pattern of change in empathy from middle childhood to early adolescence. To identify the best error structure, we compared a number of nested models that differed only in the random effect of interest and used deviance tests to determine the statistical significance of the random effects (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Because the difference between two nested models in their deviances (i.e., −2 log likelihood) was chi-squared distributed, it indicated whether adding a particular set of random variance components constituted a significantly better error structure. Non-nested models with different random variance components, however, were compared based on Information Criteria, including AIC and BIC. Second, we tested a gender-specific change model (Model 2) to examine whether, controlling for youths’ birth order and pubertal status and parental education, the pattern of change in empathy differed for girls versus boys. Third, we tested a sibling relationship model (Model 3) to examine whether, controlling for parental responsiveness and marital love, within-person changes in sibling warmth and conflict were associated with within-person changes in youths’ empathy. We also included the interactions between sibling relationship qualities and youths’ birth order and age to test whether these associations were stronger for second-borns (versus firstborns) and for older youths (versus younger youths). We only included significant interactions in the final models, because retaining nonsignificant interactions tends to increase standard errors (Aiken & West, 1991). The equations for Models 1, 2, and 3 can be found in the Appendix.

MLM Models

Coefficients for fixed and random effects can be found in Table 2. Deviance tests revealed that the addition of a random linear slope at Level 2, X2(2) = 6.9, p < .05, or at Level 3, X2(2) = 6.2, p < .05, significantly improved the fit of an intercept-only model. However, Information Criteria indicated that, with the same number of degrees of freedom, the model with a random linear slope at Level 2 (AIC = 4693.1; BIC = 4709.6) had a better fit than a model with a random linear slope at Level 3 (AIC = 4693.8; BIC = 4710.3), and thus the former was selected as the error structure against which the fixed effects were tested. Model 1 revealed a significant quadratic effect of age. As Figure 1 shows, overall (girls’ and boys’ scores combined), empathy increased steadily from age 7 to about age 12 and then leveled off. Model 2 revealed a significant main effect for gender, indicating that, at age 11 (the age at which our time variable was centered), the difference in empathy between girls (M = 7.83; SD = 1.56) and boys (M = 5.96; SD = 2.00) was significant. A significant Linear Time × Gender interaction further indicated that, at age 11, the positive linear effect was significant for girls, γ = 0.21, SE = 0.06, p < .01, but not for boys, γ = −0.03, SE = 0.06, n.s. As Figure 1 shows, girls in general reported higher levels of empathy than boys, and girls’ empathy increased from age 7 to about age 12 and then leveled off, but boys’ empathy remained relatively unchanged over time.

Table 2.

Coefficients (γ) and Standard Errors (SE) for Multilevel Models of Empathy

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ | SE | γ | SE | γ | SE | |

| Fixed parameters | ||||||

| Intercept (γ000) | 6.92** | 0.10 | 8.06** | 0.17 | 7.82** | 0.16 |

| Age (γ100) | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.21** | 0.06 | 0.26** | 0.06 |

| Age2 (γ200) | −0.04** | 0.01 | −0.03* | 0.01 | −0.03* | 0.01 |

| Gender (γ010) | −2.04** | 0.14 | −1.86** | 0.14 | ||

| Linear time × Gender (γ110) | −0.24** | 0.07 | −0.26** | 0.07 | ||

| Birth order (γ020) | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.34* | 0.15 | ||

| Pubertal transition (γ300) | −0.17 | 0.18 | −0.11 | 0.17 | ||

| Parental education (γ001) | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.04 | ||

| BP sibling warmth (γ030) | 0.08** | 0.02 | ||||

| WP sibling warmth (γ400) | 0.03* | 0.01 | ||||

| Linear time × WP sibling warmth (γ500) | 0.02** | 0.01 | ||||

| BP sibling conflict (γ040) | −0.01 | 0.02 | ||||

| WP sibling conflict (γ600) | −0.06** | 0.01 | ||||

| Parental responsiveness (γ700) | 0.07** | 0.01 | ||||

| Marital love (γ800) | 0.09 | 0.09 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Random parameters | ||||||

| L3 intercept (τ000) | 0.45* | 0.21 | 0.45** | 0.15 | 0.47** | 0.13 |

| L2 intercept (τ00k) | 1.94** | 0.26 | 0.95** | 0.17 | 0.72** | 0.14 |

| L2 age (τ110) | 0.07† | 0.05 | 0.07* | 0.04 | 0.05† | 0.04 |

| L2 intercept-age covariance (τ01k = τ10k) | 0.16* | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Residual (eijk) | 1.55** | 0.09 | 1.53** | 0.09 | 1.45** | 0.08 |

Note. BP = between-person; WP = within-person; L3 = Level 3; L2 = Level 2.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01.

Model 3 revealed a significant between-person effect for sibling warmth, indicating that youths who reported closer relationships with their siblings, on average, were more empathic. A significant Linear Time × Within-Person Sibling Warmth interaction, together with follow-up tests, indicated that a significant within-person association between sibling warmth and youths’ empathy emerged at age 11, γ = 0.03, SE = 0.01, p < .05, and became stronger over time, increasing by 0.02 units each year. In other words, starting around age 11, at times when youths reported more sibling warmth than usual (i.e., compared to their own cross-time average), they also reported more empathy than usual. Model 3 also revealed a significant within-person effect for sibling conflict, indicating that, at times when youths reported more sibling conflict than usual, they also reported less empathy than usual. The interactions between sibling relationship qualities and birth order and other interactions involving youths’ age were not significant, and thus were dropped from the final model. Exploratory analyses testing for interactions between sibling relationship qualities and youths’ gender revealed no differences in the associations between sibling warmth and conflict and youths’ empathy for girls versus boys.

Discussion

Although recent research has highlighted socioemotional competencies as key components of youths’ positive development (Spinrad & Eisenberg, 2009), most studies on empathy – an important precursor of prosocial behaviors (Eisenberg et al., 2009; Hoffman, 2001) – are cross-sectional, and research on the role of the family has focused almost exclusively on parental socialization. Using a MLM strategy to take full advantage of 3-wave, longitudinal data collected from two siblings from each of about 200 families, this study expanded upon previous work by examining the developmental course of empathy from age 7 to 14 and the within-person associations between sibling warmth and conflict and youths’ empathy. Our results indicated that, as predicted by gender intensification theory (Galambos et al., 2009; Rose & Rudolph, 2006), the patterns of change in empathy were different for girls and boys, resulting in a widening gender gap across the transition to adolescence. Moreover, consistent with the idea that sibling interactions afford unique social experiences and learning opportunities (Dunn, 2002; Katz et al., 1992), even controlling for parental responsiveness and marital love, sibling warmth was associated positively and sibling conflict was associated negatively with both firstborns’ and second-borns’ empathy. Interestingly, the within-person association between sibling warmth and youths’ empathy became stronger with age, suggesting that siblings may play an increasingly important role in shaping each other’s socioemotional development during adolescence.

Empathy Development in Adolescence

Our study showed that girls’ empathy increased across the transition to adolescence and then leveled off at about age 12. This finding is in line with research indicating that brain regions implicated in social cognitive processing continue to develop into adolescence (Decety, 2010) and that increasing involvement with peers presents new opportunities and motivation for adolescents to practice their problem solving and interpersonal negotiation skills (Eisenberg et al., 2009). In contrast, for boys, the quadratic effect for time was significant but the linear effect was not, suggesting that boys’ empathy increased temporarily at the transition to adolescence but then declined. Nevertheless, the magnitude of this increase, as shown in Figure 1, was so modest that it was probably of little practical significance (Kirk, 1996). The differential development of girls and boys resulted in an increasing gender difference in empathy over time, providing support to a theory that gender socialization pressure intensifies during adolescence (Galambos et al., 2009). It is noteworthy that youths’ pubertal status and parental education were controlled in the analyses, and thus the observed patterns of change were unlikely to be due to gender differences in self- or others’ reactions to observable physical changes (Hyde et al., 2008) or to social class differences in youths’ perspective-taking and emotion understanding (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002).

Although gender differences in certain cognitive and socioemotional characteristics have been found to have a neural and hormonal basis (Galambos et al., 2009), the differential trajectories for girls and boys documented here may reflect differences in empathic tendencies rather than capacities. A person who has acquired the abilities to infer internal states and take another’s perspective may not use these abilities in everyday life. Empathic responding often involves apprehending suffering, sorrow, and other negative emotions experienced by others (Rosenblum & Lewis, 2008). Individuals who have poor self-regulation of emotions, for example, may be overwhelmed by high levels of negative arousal, which may prompt them to preempt an empathic response, flee an emotional situation, or prematurely terminate an empathic connection. Gender differences in tolerance of negative affect may underlie the observed differences in empathic tendencies between girls and boys. Gender socialization, which encourages females to be expressive and nurturant and males to be analytical and instrumental (Galambos et al., 2009), also may contribute to this difference. Of particular interest here is the observation that boys, but not girls, become increasingly reluctant to express negative affect and tender feelings over time (Eisenberg & Fabes, 1990). Recent research has demonstrated that male restrictive emotionality is associated with a wide range of psychological disorders and behavioral problems, including depression, substance use, and antisocial behaviors (O’Neil, 2008). Teaching children and adolescents, particularly boys, to understand others’ emotions and to express their own feelings in appropriate ways may be an important component in promoting youths’ social competence and prosocial behaviors (Hoffman, 2001; Spinrad & Eisenberg, 2009).

Only a handful of studies are available on longitudinal changes in empathy, and they mainly have been conducted in mid- and late adolescence. Their results are also mixed, with Davis and Franzoi (1991) showing that empathy increased from age 15 to 18, Eisenberg et al. (2005) showing that perspective taking increased from age 15 to 26 but that sympathy did not change over time, and Mestre et al. (2009) showing that girls’ empathy increased at a faster rate than did boy’s from age 13 to 14. Due to differences in sample sizes, nationality, and data analytic strategies (especially how developmental time was operationalized), comparisons between these and our study are difficult. One potential explanation for the discrepancy in the findings, however, pertains to the use of different measures. The use of Bryant’s (1982) Index of Empathy for Children and Adolescents, which focuses on youths’ spontaneous empathic responses to others’ feelings, seems to reveal less drastic changes beginning in early adolescence (our study; Mestre et al., 2009). On the other hand, the use of Davis’s (1983) Interpersonal Reactivity Index, which includes additional items on strategic use of empathic skills (e.g., “I try to look at everybody’s side of a disagreement before I make a decision,” “I sometimes try to understand my friends better by imagining how things look from their perspective”), appears to capture a continuous increase in empathy through mid- and late adolescence (Davis & Franzoi, 1991; Eisenberg et al., 2005; Mestre et al., 2009). As pointed out by a number of researchers, the phenomenal experience of empathy is highly complex, involving a large array of cortical and subcortical brain structures (Decety, 2010) and emerging through repeated interactions across different social situations (Eisenberg et al., 2009). Deliberate, goal-directed use of such complex, emotional experience may require additional cognitive efforts and special interpersonal skill practice (Izard, 2009). Long-term longitudinal studies of adolescents that distinguish between spontaneous and strategic empathy have the potential to reconcile these findings.

Sibling Relationships and Empathy

Our findings indicated that youths who had closer relationships with their siblings, on average, reported higher levels of empathy. The unique contribution of our study, however, lies in the discovery that, even controlling for time-varying parental responsiveness and marital love, at times when youths reported more warmth and less conflict with their siblings than usual, they also reported more empathy than usual. Our use of time-varying covariates and inclusion of time-varying controls helped to rule out multiple alternative explanations, including stable individual differences (Singer & Willett, 2003), parental socialization (Brody, 1998; Eisenberg et al., 2009), and marital dynamics (Brody, 1998; Grych & Fincham, 1990), and thus provided for stronger inferences about the links between sibling relationship qualities and youths’ empathy. Ample evidence suggests that parents play a major role in enhancing children’s awareness and understanding of others’ feelings (Eisenberg et al., 2009; Hoffman, 2001). Our study added to this work by showing that, although family subsystems are inter-related (Minuchin, 1985), siblings also may serve as significant agents of socialization and contribute to each other’s socioemotional development in unique ways. Our focus on concurrent, within-person associations, however, means that our results cannot determine whether sibling relationships foster empathy development and/or whether youths’ empathy promotes positive sibling interactions. Future researchers should test directions of effect using lagged, time-varying predictors (e.g., lagging the time-varying covariates by one year) that can shed light on both temporal precedence and within-person associations (Singer & Willett, 2003).

Despite their correlation, sibling warmth and conflict each explained unique variance in youths’ empathy, lending support to a multidimensional approach to conceptualizing sibling relationships (Brody, 1998; East, 2009) and reflecting the observation that intensely positive and negative exchanges can coexist within the same sibling dyad (Dunn, 2002). In contrast to other findings that sibling conflict may provide opportunities for youths to develop perspective-taking and persuasive negotiation skills (Katz et al., 1992), however, our results suggested that sibling conflict was linked negatively to youths’ empathy (Howe et al., 2001). This is not completely surprising, given that our measure was designed to assess how often sibling conflict occurred across a variety of domains, but not how the conflict was usually handled, which has been shown to be crucial in determining whether or not conflict will benefit those who are involved (Ross et al., 2006). Studies that pay close attention to interaction details, such as siblings’ use of conflict resolution skills and negotiation strategies, would provide further insights into the potentially beneficial role of sibling conflict in adolescent socioemotional development.

In contrast to Tucker et al.’s (1999) findings that sibling warmth was associated with second-borns’, but not firstborns’, empathy, our results indicated that the sibling relationship effects did not vary by birth order. In childhood, different-age siblings may differ substantially in socioemotional competencies. Five-year-old children who begin to understand that individuals’ beliefs and desires may affect their feelings about a given event may seem to be more empathic than their 2-year-old siblings, who have just acquired the concept of self-other categorization (Decety, 2010). Thus, it is not surprising that prior early childhood research has tended to study older siblings’ influences on their younger siblings (Azmitia & Hesser, 1993; Dunn et al., 1991). The relative developmental difference between siblings diminishes rapidly, however, from middle childhood to early adolescence (East, 2009), when the same 3-year gap between siblings’ ages may tell us less about how different they are in socioemotional competencies. To the extent that adolescent-aged siblings are more developmentally similar, they may have more opportunities to engage in reciprocal interactions, which in turn promote the perspective taking and interpersonal skills that underlie empathy (Dunn, 1998; Harris, 1994). On a methodological level, our MLM framework also allowed us to include multiple waves of longitudinal data from each sibling in the same model, and thus maximized the statistical power (Singer & Willett, 2003) of detecting the association between sibling relationship qualities and empathy for both firstborns and second-borns.

Perhaps even more importantly, our findings indicated that the within-person association between sibling warmth and youths’ empathy emerged at the transition to adolescence and became stronger over time. Although tremendous advances have been made in understanding the nature and implications of sibling relationships (Brody, 1998; East, 2009), sibling influences rarely have been examined in a developmental framework (Dunn, 2005). It remains relatively unknown, for example, whether the impact of siblings on youths’ socioemotional development changes over time. Our study addressed this issue by directly testing the interaction effects between sibling relationship qualities and youths’ ages on their empathy during the transition to adolescence, when youths become more involved in the world beyond their families. Because little prior research is available for comparison, our results should be treated as a first step in understanding this process. At an age when youths become increasingly motivated to gain independence from their parents and to forge deep friendships with their peers, the more reciprocal nature of the sibling relationship may make it an attractive and effective family context in which youths learn and practice social competencies (Howe et al., 2001). The mutual influences of siblings in shaping each other’s socioemotional development, especially during adolescence, merit further investigations. Although many other social (e.g., peer influences) and contextual (e.g., school experiences and community involvement) factors also may play a role (Eisenberg et al., 2009), from the perspectives of parents and practitioners, strategies that promote sibling warmth and develop conflict resolution skills may represent an important focus of education and programing directed at advancing youths’ socioemotional competencies (Feinberg, Solmeyer, & McHale, 2012).

Limitations and Conclusions

Our study had several limitations. First, although our sample reflected some population characteristics of married-couple families from the state where the study was conducted (US Census Bureau, 2000), it was ethnically homogeneous and not representative of the diversity of youths in the US. Given the notable ethnic differences in family socialization, emotion display rules, and other socioemotional characteristics (Chen & French, 2008), our findings need to be replicated in more diverse samples. Second, our measure of empathy was unidimensional and only able to capture the general level of youths’ empathy. Increasing evidence suggests that empathy involves multiple cognitive and socioemotional components, each of which may have its own distinct developmental trajectory (Decety, 2010). Moreover, as described above, spontaneous and strategic empathy may have different patterns of change. Future research should study different forms and aspects of empathy separately and explore how each develops over time. A related issue is that we used a self-report measure of empathy, and thus our results may be influenced by youths’ self-presentation biases. The incorporation of nonverbal measures, such as facial and other physiological responses as well as behavioral observations, would be useful for validating our findings on empathy development (Eisenberg & Fabes, 1990). Third, although our use of time-varying covariates and time-varying controls helped to account for alternative explanations, definitive conclusions about causal relationships cannot be made based on correlational data. Intervention and prevention studies that use experimental designs, with random assignment to intervention versus control conditions, to introduce changes to sibling interactions and measure subsequent differences in youths’ socioemotional outcomes (Feinberg et al., 2012) are required to disentangle the causal paths underlying the associations documented here.

Adolescence is a period when youths experience multiple biological and social changes and become more involved in relationships with peers and others outside the family (Decety, 2010; Eisenberg et al., 2009). With a focus on both longitudinal and within-person changes, our study contributed to the understanding of this important period by demonstrating that girls and boys exhibited differential development in empathy (Galambos et al., 2009; Rose & Rudolph, 2006) and that siblings continued to play a unique role in shaping each other’s socioemotional characteristics (Dunn, 1998; East, 2009) across the transition to adolescence. Our approach to directly testing the interaction effects between sibling relationship qualities and chronological age on empathy also provided new insights about the potentially increasing significance of sibling relationships over time (Dunn, 2005). On an applied level, our findings highlighted the importance of teaching youths, especially boys, to understand others’ and their own emotions (O’Neil, 2008) and underscored the potential of targeting siblings in efforts to promote youths’ socioemotional competencies (Feinberg et al., 2012).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the graduate and undergraduate assistants, staff, and faculty collaborators for their help in conducting this study, as well as the participating families for their time and insights about youth development. This work was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01-HD32336) to Ann C. Crouter and Susan M. McHale, Co-Principal Investigators.

Appendix. Equations for Multilevel Models of Empathy

Model 1

Level 1 equation

Empathyijk = π0jk + πijk × age + π2jk × age2 + eijk

Level 2 equations

π0jk = β00k + u0jk

π1jk = β10k + u1jk

π2jk = β20k

where

Level 3 equations

β00k = γ000 + u00k

β10k = γ100

β20k = γ200

where u00k ~ N (0, τ000)

Model 2

Level 1 equation

Empathyijk = π0jk + πijk × age + π2jk × age2 + π3jk × Pubertal transition + eijk

Level 2 equations

π0jk = β00k + β01k × Gender + β02k × Birth order + u0jk

π1jk = β10k + β11k × Gender + u1jk

π2jk = β20k

π3jk = β30k

where

Level 3 equations

β00k = γ000 + γ001 × Parental education + u00k

β01k = γ010

β02k = γ020

β10k = γ100

β11k = γ110

β20k = γ200

β30k = γ300

where u00k ~ N (0, τ000)

Model 3

Level 1 equation

Empathyijk = π0jk + π1jk × age2 + π2jk × age + π3jk × Pubertal transition + π4jk × WP sibling warmth + π5jk × age × WP sibling warmth + π6jk × WP sibling conflict + π7jk × Parental responsiveness + π8jk × Marital love + eijk

Level 2 equations

π0jk = β00k + β01k × Gender + β02k × Birth order + β03k × BP sibling warmth + β04k × BP sibling conflict + u0jk

π1jk = β10k + β11k × Gender + u1jk

π2jk = β20k

π3jk = β30k

π4jk = β40k

π5jk = β50k

π6jk = β60k

π7jk = β70k

π8jk = β80k

where

Level 3 equations

β00k = γ000 + γ001 × Parental education + u00k

β01k = γ010

β02k = γ020

β03k = γ030

β04k = γ040

β10k = γ100

β11k = γ110

β20k = γ200

β30k = γ300

β40k = γ400

β50k = γ500

β60k = γ600

β70k = γ700

β80k = γ800

where u00k ~ N (0, τ000)

Note. BP = between-person; WP = within-person.

Subscripts i indicates occasions within individual j in family k, j indicates individuals within family k, and k indicates families.

Footnotes

Portions of this article were presented at the Society for Research on Adolescence Biennial Meeting, Vancouver, Canada, March 2012.

Contributor Information

Chun Bun Lam, He received his Ph.D. in Human Development and Family Studies from the Pennsylvania State University. His major research interests include family relationships and dynamics, youth adjustment and well-being, and gender and sexuality. This manuscript was prepared while he was a doctoral student at the Pennsylvania State University..

Anna R. Solmeyer, She received her Ph.D. in Human Development and Family Studies from the Pennsylvania State University. Her major research interests include family relationships and dynamics, with a specific focus on the sibling subsystem, and family-based prevention/intervention programing..

Susan M. McHale, The Pennsylvania State University; She received her Ph.D. in Developmental Psychology from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her research interests include family relationships and dynamics, youth adjustment and development, and the roles of gender and culture in these phenomena..

References

- Adams GR. Social competence during adolescence: Social sensitivity, locus of control, and peer popularity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1983;12:203–211. doi: 10.1007/BF02090986. doi: 10.1007/BF02090986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Worthman C. Puberty and depression: The role of age, pubertal status and pubertal timing. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:51–61. doi: 10.1017/s003329179700593x. doi: 10.1017/S003329179700593X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azmitia M, Hesser J. Why siblings are important agents of cognitive development: A comparison of siblings and peers. Child Development. 1993;64:430–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02919.x. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braiker HB, Kelley HH. Conflict in the development of close relationships. In: Burgess RL, Huston TL, editors. Social exchange in developing relationships. Academic; New York, NY: 1979. pp. 135–168. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH. Sibling relationship quality: Its causes and consequences. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;49:1–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.1. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant B. An index of empathy for children and adolescents. Child Development. 1982;53:413–425. doi: 10.2307/1128984. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, French D. Children’s social competence in cultural context. Annual Review of Psychology. 2008;59:591–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093606. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Toyokawa T. Construction and validation of the parenting styles inventory II (PSI-II) 1997 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;44:113–126. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113. [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH, Franzoi SL. Stability and change in adolescent self-consciousness and empathy. Journal of Research in Personality. 1991;25:70–87. doi: 10.1016/0092-6566(91)90006-C. [Google Scholar]

- Decety J. The neurodevelopment of empathy in humans. Developmental Neuroscience. 2010;32:257–267. doi: 10.1159/000317771. doi: 10.1159/000317771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey DB, Condron DJ. Playing well with others in kindergarten: The benefit of siblings at home. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:333–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2004.00024.x. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J. Siblings, emotion, and the development of understanding. In: Bråten S, editor. Intersubjective communication and emotion in early ontogeny. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1998. pp. 158–168. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J. Sibling relationships. In: Smith PK, Hart CH, editors. Blackwell handbook of childhood social development. Blackwell; Malden, MA: 2002. pp. 223–237. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J. Commentary: Siblings in their families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:654–657. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.654. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J, Brown J, Slomkowski C, Tesla C, Youngblade L. Young children’s understanding of people’s feelings and beliefs: Individual differences and their antecedents. Child Development. 1991;62:1352–1366. doi: 10.2307/1130811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J, Munn P. Becoming a family member: Family conflict and the development of social understanding in the second year. Child Development. 1985;56:480–492. doi: 10.2307/1129735. [Google Scholar]

- East PL. Adolescents’ relationships with siblings. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 3rd ed Vol. 2, Contextual influences on adolescent development. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2009. pp. 43–73. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N. The development of empathy-related responding. In: Carlo G, Edwards CP, editors. Moral motivation through the life span. University of Nebraska Press; Lincoln, NE: 2005. pp. 73–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC, Shepard SA. Age changes in prosocial responding and moral reasoning in adolescence and early adulthood. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2005;15:235–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2005.00095.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2005.00095.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA. Empathy: Conceptualization, measurement, and relation to prosocial behavior. Motivation and Emotion. 1990;14:131–149. doi: 10.1007/BF00991640. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Morris AS, McDaniel B, Spinrad TL. Moral cognitions and prosocial responding in adolescence. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 3rd ed Vol. 1, Individual bases of adolescent development. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2009. pp. 229–265. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME, Solmeyer AR, McHale SM. The third rail of family systems: Sibling relations, mental and behavioral health, and preventive intervention in childhood and adolescence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2012;15:43–57. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0104-5. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0104-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galambos NL, Berenbaum SA, McHale SM. Gender development in adolescence. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 3rd ed Vol. 1, Individual bases of adolescent development. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2009. pp. 305–357. [Google Scholar]

- Grühn D, Rebucal K, Diehl M, Lumley M, Labouvie-Vief G. Empathy across the adult lifespan: Longitudinal and experience-sampling findings. Emotion. 2008;8:753–765. doi: 10.1037/a0014123. doi: 10.1037/a0014123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Fincham FD. Marital conflict and children’s adjustment: A cognitive-contextual framework. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:267–290. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.267. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PL. The child’s understanding of emotion: Developmental change and the family environment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1994;35:3–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01131.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman ML. Empathy and moral development: Implications for caring and justice. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Howe N, Aquan-Assee J, Bukowski WM, Lehoux PM, Rinaldi CM. Siblings as confidants: Emotional understanding, relationship warmth, and sibling self-disclosure. Social Development. 2001;10:439–454. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00174. [Google Scholar]

- Howe N, Ross HS. Socialization, perspective-taking, and the sibling relationship. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:16–165. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.26.1.160. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde JS, Mezulis AH, Abramson LY. The ABCs of depression: Integrating affective, biological and cognitive models to explain the emergence of the gender difference in depression. Psychological Review. 2008;115:291–313. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.291. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE. Emotion theory and research: Highlights, unanswered questions, and emerging issues. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163539. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karniol R, Gabay R, Ochion Y, Harari Y. Is gender or gender-role orientation a better predictor of empathy in adolescence? Sex Roles. 1998;39:45–59. doi: 10.1023/A:1018825732154. [Google Scholar]

- Katz LF, Kramer L, Gottman JM. Conflict and emotions in marital, sibling, and peer relationships. In: Shantz CU, Hartup WW, editors. Conflict in child and adolescent development. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1992. pp. 122–149. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk RE. Practical significance: A concept whose time has come. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1996;56:746–759. doi: 10.1177/0013164496056005002. [Google Scholar]

- Krevans J, Gibbs JC. Parents’ use of inductive discipline: Relations to children’s empathy and prosocial behavior. Child Development. 1996;67:3263–3277. doi: 10.2307/1131778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PA, Guo SS, Kulin HE. Age of puberty: Data from the United States of America. APMIS. 2001;109:81–88. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2001.d01-107.x. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2001.d01-107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDermid SM, Huston TL, McHale SM. Changes in marriage associated with the transition to parenthood: Individual differences as a function of sex-role attitudes and changes in the division of household labor. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52:475–486. doi: 10.2307/353041. [Google Scholar]

- Mestre MV, Samper P, Frías MD, Tur AM. Are women more empathetic than men? A longitudinal study in adolescence. The Spanish Journal of Psychology. 2009;12:76–83. doi: 10.1017/s1138741600001499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin P. Families and individual development: Provocations from the field of family therapy. Child Development. 1985;56:289–302. doi: 10.2307/1129720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D, Endresen IM. The importance of sex-of-stimulus object: Age trends and sex differences in empathic responsiveness. Social Development. 1998;7:370–388. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00073. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil JM. Summarizing twenty-five years of research on men’s gender role conflict using the Gender Role Conflict Scale: New research paradigms and clinical implications. The Counseling Psychologist. 2008;36:358–445. doi: 10.1177/0011000008317057. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Crockett LJ, Richards MH, Boxer AM. Measuring pubertal status: Reliability and validity of a self-report measure. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1988;7:117–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Rudolph KD. A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:98–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum GD, Lewis M. Emotional development in adolescence. In: Adams GR, Berzonsky MD, editors. Blackwell handbook of adolescence. Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 2008. pp. 269–289. [Google Scholar]

- Ross H, Ross M, Stein N, Trabasso T. How siblings resolve their conflicts: The importance of first offers, planning, and limited opposition. Child Development. 2006;77:1730–1745. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00970.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saklofske DH, Eysenck SBG. Impulsiveness and venturesomeness in Canadian children. Psychological Reports. 1983;52:147–152. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1983.52.1.147. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1983.52.1.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willet JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Spinrad TL, Eisenberg N. Empathy, prosocial behavior, and positive development in schools. In: Gilman R, Huebner ES, Furlong MJ, editors. Handbook of positive psychology in schools. Routledge; New York, NY: 2009. pp. 119–29. [Google Scholar]

- Staub E. The origins of caring, helping, and nonaggression: Parental socialization, the family system, schools, and cultural influence. In: Pearl PM, Oliner SP, Baron L, Blum LA, Krebs DL, Smolenska MZ, editors. Embracing the other: Philosophical, psychological, and historical perspectives on altruism. New York University Press; New York, NY: 1992. pp. 390–412. [Google Scholar]

- Stocker CM, McHale SM. The nature and family correlates of preadolescents’ perceptions of their sibling relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1992;9:179–195. doi: 10.1177/0265407592092002. [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Bellanti CJ, Bierman KL. The quality of sibling relationships and the development of social competence and behavioral control in aggressive children. Development Psychology. 1996;32:79–89. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.32.1.79. [Google Scholar]

- Strayer J, Roberts W. Facial and verbal measures of children’s emotions and empathy. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1997;20:627–649. doi: 10.1080/016502597385090. [Google Scholar]

- Tonks J, Williams WH, Frampton I, Yates P, Slater A. Assessing emotion recognition in 9-15-years olds: Preliminary analysis of abilities in reading emotions from faces, voices, and eyes. Brain Injury. 2007;21:623–629. doi: 10.1080/02699050701426865. doi: 10.1080/02699050701426865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker CJ, Updegraff KA, McHale SM, Crouter AC. Older siblings as socializers of younger siblings’ empathy. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19:176–198. doi: 10.1177/0272431699019002003. [Google Scholar]

- US Bureau of Statistics Census 2000 gateway. 2000 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/main/www/cen2000.html.

- Whiteman SD, McHale SM, Crouter AC. Longitudinal changes in marital relationships: The role of offspring’s pubertal development. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:1005–1020. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00427.x. [Google Scholar]